Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

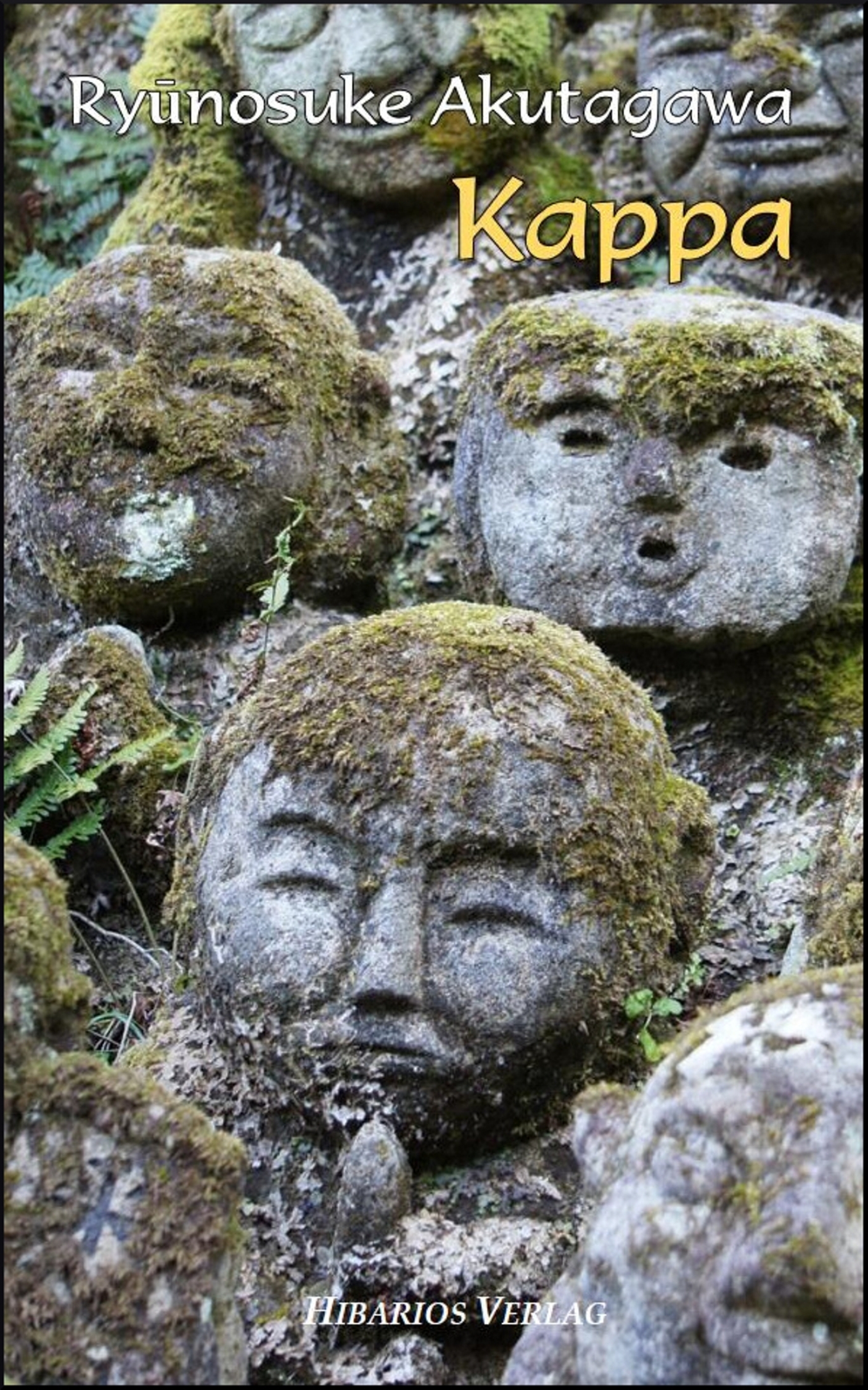

A surreal masterpiece from one of Japan's greatest writers In early 20th-century Japan, a lone hiker falls through a hole in the ground into Kappaland. This is a place ruled by amphibious creatures who share characteristics with tigers and turtles, but who, for all their strangeness, shed light on the human condition. In Kappaland children choose whether or not to be born, intellectuals think nothing of drinking themselves to death as part of a cultural demonstration, unemployed workers are saved the bother of supporting themselves by being turned into sandwich meat, and artistic rebels from the human realm are enshrined in the Great Tabernacle as saints. Gruesome as life is there in some ways, the Kappas are refreshingly honest about their practices, and it's a return to the world above that drives the narrator insane and sends him to the mental asylum. This novel, the last work by icon of Japanese letters Ryunosuke Akutagawa, is a darkly comic and surreal satire, which challenges all the conventions of so-called polite society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 164

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘A tiny book with an irresistible quality… exquisite’

SUNDAY TIMES

‘A classic of our times’

SCOTSMAN

‘The quintessential writer of his era’

DAVID PEACE

‘He was both traditional and experimental and always compelling and fearless… There is no writer quite like him’

HOWARD NORMAN

‘Extravagance and horror are in his work, but never in his style, which is always crystal clear’

JORGE LUIS BORGES 2

3

KAPPA

RYUNOSUKE AKUTAGAWA

TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE BY GEOFFREY BOWNAS

INTRODUCTION BY G.H. HEALEY

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS4

KAPPA

Contents

Note on Names

Names in the text are given in the usual Japanese order; family name first, given name second. Thus, in Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Akutagawa is the family name and Ryūnosuke the given name.

Japanese writers commonly adopt a gō, or pen-name, which replaces the given name. Natsume Kinnosuke, for example, adopted the gō Sōseki. It is usual to refer to a writer by his gō, if he has one: Sōseki, (Nagai) Kafū, or by his family name if he has not: Kikuchi (Kan), Kume (Masao). Akutagawa, however, is usually referred to by his given name. 10

Introduction

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke was born on 1 March 1892, in Irifunechō, a district of what was then the Borough of Kyōbashi, in Tokyo. He was the last of the three children born to Niihara Toshizō and his first wife, Fuku. Of the other two children, both girls, only the younger, Hisa, survived, her sister Hatsu having died of meningitis about a year before Ryūnosuke’s birth.

In those days, foreign residents in Japan were permitted to live only in certain areas designated Foreign Settlements. The part of Irifunechō in which Ryūnosuke was born lay within the confines of the Tsukiji Foreign Settlement and only two other Japanese families lived in the immediate neighbourhood. It was the presence of foreigners that had attracted Niihara Toshizō there: he was a dairyman, and the demand for milk, butter and cream (still somewhat exotic foods to the Japanese) was greatest in the foreign community.

Toshizō had been born in Western Japan in 1851. In 1868, the Tokugawa Shōgunate collapsed and power was restored to the Emperor. Toshizō fought as a young man in the Boshin War of that year, in which the adherents of the old regime were defeated by the armies of the new Imperial Government. He later worked for some years on a dairy 12farm at Hakone before setting up in business for himself in Irifunechō in 1883. He was an energetic and enterprising man, and he prospered. By the time of Ryūnosuke’s birth, he was the owner of five dairies.

But the vigour of his nature also manifested itself in less admirable ways. He had a violent temper and was involved in frequent quarrels. In a memoir of his father written in 1926 Ryūnosuke recounts an incident that illuminates this facet of his father’s character:

Once when I was in the third year at Middle School I took my father on at wrestling. I sent him sprawling with my favourite throw, the ōsotogari. He sprang up and said, advancing on me, ‘Another go!’ I threw him again, with no trouble at all. He rushed at me a third time, his expression furious: ‘Another go!’ My aunt, who was watching… frowned at me… and when we closed I purposely fell on my back. (Tenkibo, Chikuma Shobō 3, 307–8.)*

Toshizō was a commoner, but his wife, Fuku, came from the warrior class which had dominated Japanese society for centuries. Since the Restoration, the samurai had been deprived of the privileged position they had held under the Shōgunate. Many of them had been forced into occupations they considered beneath their dignity: they had joined the new conscript army, or become policemen, or entered trade. 13In name, however, they still formed a distinct class, and had considerable pride in their ancestry. According to one of Ryūnosuke’s biographers (his cousin Kuzumaki Yoshitoshi) Fuku’s family, the Akutagawas, looked down on Toshizō as a parvenu.

Fuku was a slender, graceful woman, and was regarded as something of a beauty. Temperamentally, she was quite unlike her husband, and life with him cannot have been easy for her. Her younger daughter, Hisa, remembered her as an extremely timid woman who spoke little and was inclined to conceal her feelings. But she was more than merely diffident. Her withdrawn-ness was the emotional self-defence of a schizoid personality, the deterioration of which was precipitated by two events: Hatsu’s death and Ryūnosuke’s birth. The death of her elder daughter was a blow that Fuku was in any case particularly ill-equipped to withstand, and its effect on her was worsened by self-recrimination, for she believed that the meningitis of which Hatsu had died had developed from a cold the child had caught while the two of them were out for the day together. Within a few months of Hatsu’s death, Fuku had become pregnant again. This pregnancy was a source of deep anxiety to her, for what may appear a rather curious reason. This was that the birth would take place in 1892, the thirty-third year of her life and the forty-second of her husband’s. A woman’s thirty-third year and a man’s forty-second were regarded by the superstition of the day as periods of great danger, so that there could hardly have been a less auspicious time for the birth of a child. Ryūnosuke’s parents were concerned enough to take steps to avert the 14threatened ill luck. After his birth, they formally ‘abandoned’ him. He was ‘taken in’ by Matsumura Senjirō, an old friend of Toshizō’s who managed one of his dairies. It was then possible for him to be accepted back into the family as though he were a foundling, the unfortunate circumstances of his birth thus neutralized.

These unhappy experiences were enough to loosen Fuku’s already precarious hold on reality, and a few months after Ryūnosuke’s birth she lapsed into a schizophrenic state from which she never recovered, although she lived on for another ten years.

Ryūnosuke, of course, only knew her as she was after she had become ill. In 1926 he wrote this description of her:

My mother was a madwoman… She used to sit alone in the house at Shiba, her hair in a bun held by a comb, puffing at a long pipe. She was a small woman, with a small face that was somehow grey and entirely without animation… I remember that on one occasion when I went upstairs with my foster-mother to say hello to her, all of a sudden she hit me on the head with her pipe. But she was usually a very placid lunatic. When my sister or I pestered her to, she would draw pictures for us on sheets of writing paper… But the people she drew all had foxes’ faces. (Tenkibo, Chikuma Shobō 3, 305.)

His mother’s madness, and the fear that he might have inherited it, preyed on Ryūnosuke’s mind throughout his life. Bad heredity is one of the objects of his satire in Kappa: 15

There was a huge poster at a street corner. The lower half of the poster showed figures of a dozen or so Kappas; some of these figures were blowing trumpets, others brandished swords. The whole of the rest of the surface of the poster was taken up by writing in Kappa script; it is not an attractive form of script—it is spiral and looks for all the world like so many watch springs. I think I’ve got the broad gist of what these spiral characters said, though here again there could well be mistakes of detail, I’m afraid. At any rate, I did my best under the circumstances:

Let’s recruit our Heredity Volunteer Troop

Let all hale and hearty Kappas

Marry unsound and unhealthy Kappas

To eradicate evil heredity. (See pp. 65–6.)

Since Fuku was no longer capable of looking after her children, Ryūnosuke was put into the care of her elder brother Akutagawa Michiaki and his wife Tomo, who were themselves childless. He was brought up as Michiaki’s son, but was not formally adopted into the Akutagawa family until 1904, two years after his mother’s death.

The characters of Ryūnosuke’s father and foster-father could hardly have been more different. Unlike the irascible Toshizō, Michiaki was a large, sedate man who always smiled faintly as he talked. He evidently lacked Toshizō’s energy and commercial acumen: after his retirement from the Civil Service in 1904 he embarked on several business ventures, all of which failed. 16

His wife, Tomo, was remembered by one of Ryūnosuke’s friends (Tsunetō Kyō) as kindly and soft-spoken. She was the niece of Saiki Kōi, a famous aesthete of the late Edo period.

The place of Ryūnosuke’s mother, however, was taken not by Tomo but by Michiaki’s unmarried sister, Ryūnosuke’s Aunt Fuki. Fuki remained a spinster all her life. She was a dominating woman, and Ryūnosuke’s relationship with her as he grew up was very close. It was also a complicated relationship: he wrote that he loved her more than anyone else but constantly quarrelled with her; that he owed her more than anyone else but that she had made his life a misery. Undoubtedly, her influence on him was greater than that of any other member of the family. ‘If it had not been for my aunt’, he wrote, ‘I do not know whether I should be the sort of person I am today.’ (BungakusukinoKateikara, Chikuma Shobō 4, 163.)

In a fragment of autobiographical fiction written towards the end of his life, Ryūnosuke describes the household in which he spent his childhood:

Shinsuke’s family was poor, but it was not the poverty of the lowest classes, crowded together in their tenements; it was the poverty of the lower middle classes, who are obliged to suffer even greater hardships in order to keep up appearances. Apart from the interest on some savings, his father, a retired government official, had only a pension of five hundred yena year on which to keep a household of five people and a maid. The pursuit of economies was relentless… New clothes were few and far between, and 17his father made do at supper with an inferior wine that he would not have offered to a guest. His mother wore a coat to conceal her patched obi. And Shinsuke too—Shinsuke still remembers that desk of his that smelt of varnish. Although it was a second-hand desk, it looked at first glance very trim with a piece of green baize stuck on top and shiny silver mountings on the drawers. But the baize was very thin, and the drawers always stuck. More than a desk, it was a symbol of the household—a symbol of the life of a household in which appearances had to be kept up at all costs…

Shinsuke hated this poverty… he hated all the shabbiness of the house—the old tatami, the dim lamps, the peeling screens with their design of ivy-leaves… But more than the shabbiness he hated the deceitfulness that sprang from poverty. His mother would take relatives gifts of cake in boxes from the ‘Fūgetsu’ confectionery, but the contents… would have been bought at the local cake-shop. (DaidōjiShinsuke no Hansei, Chikuma Shobō 3, 231–2.)

This melancholy picture, however, is the product less of the family’s actual circumstances than of Ryūnosuke’s lifelong over-sensitivity to imagined humiliations and of the extreme depression of his last years. No doubt extravagance was avoided and some luxuries done without, but Ryūnosuke was dressed in silk as a child, and the family was well enough off to be able to keep two maids. The house they lived in, at Honjo, near the Ryōgoku bridge over the River Sumida, was a large one, set back from the street (unlike its neighbours) in a walled garden. 18

It may be objected, of course, that since DaidōjiShinsukenoHanseiis fiction it cannot be assumed that the emotions of its hero are those of its author. But the details of its hero’s life correspond so exactly to those of its author’s that it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that it is indeed an account of Ryūnosuke’s own childhood, recollected in despondency.

In a different mood, he was able to regard his childhood with greater equanimity—to recall with pleasure being taken to see the moving pictures or watching a marionette-show in the grounds of the Ekōin Temple.

The forebears of the Akutagawas were of the warrior class: men of cultivation and refinement who had for generations served the Tokugawa Shōguns as okubōzu, functionaries who, among other duties, performed the tea-ceremony for the Shōgun and saw to the entertainment of daimyōwho came up to court. The family in which Ryūnosuke was brought up was of a conservative cast of mind appropriate to its antecedents.

Japan had reopened its doors to the outside world only forty years before Ryūnosuke’s birth, after two and a half centuries of virtual isolation, and was intent on modernization, rapidly absorbing the industrial technology and adopting the political institutions of the West. Within the lifetimes of Toshizō and Michiaki, the first railway and the first iron foundry had been built, and the first modern factories established. A parliament had been created by the new constitution promulgated in 1889, and the first general election had been held in 1890.

Akutagawa Michiaki was an official of the Public Works Department of the City of Tokyo, and might have served as a 19model for the citizen of the new Japan. There is a photograph of him in steel-rimmed spectacles, wing collar and aldermanic watch-chain that might be that of the corresponding official in Manchester or Birmingham in the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

But his home life remained almost untouched by Western customs. At home, he wore Japanese dress, as his wife and sister did. His house (which was rebuilt in 1895—Ryūnosuke’s earliest memory was of the demolition of the old house in which his grandparents had lived) was of the traditional kind: a wooden structure with floors of thick straw mats, the rooms divided by sliding screens. His tastes were those of the cultured son of Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1868, when it became the capital), a city of which its inhabitants complacently said that to be born in Edo, to be born a man, and to eat the first bonito of the season were life’s three greatest joys. His recreations were playing go, a game as difficult to master as chess; composing haiku; cultivating dwarf trees; painting, in the style of the Chinese Southern School, and carving.

The members of his household shared Michiaki’s traditional tastes. The whole family practised together, under the tutelage of a master of the Itchūbushischool, the art of reciting the poetic dramas of the puppet-theatre. They went frequently to the theatre. Ryūnosuke was taken for the first time, it appears, at the age of fifteen months: ‘I am told that when Kuranosuke entered leading a horse… I cried out in delight “Horsey!”’ (BungakusukinoKateikara, Chikuma Shobō 4, 163.)

It was a family that loved literature, but the literature of the Edo period rather than the new Japanese literature that 20was being created by such writers as Tsubouchi Shōyō and Futabatei Shimei, who were deeply influenced by European literature. In 1917, Ryūnosuke wrote, ‘I have often found the material for my stories in old books. Consequently, there are people who think I spend my time searching out curiosities like some old dabbler in antiques. But not so. As a result of the old-fashioned education I received as a child, I have always read books that have little to do with the present day.’ (WatakushitoSōsaku, Chikuma Shobō 5, 347.) The family bookcases were full of Kusazōshi, the popular illustrated storybooks of the Edo period, and Ryūnosuke read them avidly. The first ‘real novel’ he read when he graduated from these storybooks was probably, he later recalled, Izumi Kyōka’s BakeIchō. But the favourite books of his childhood were the two famous Chinese novels that are called in Japanese Saiyūki(Wu Ch’eng En’s HsiYuChi) and Suikoden(the ShuiHuChuan). ‘Best loved of the books I read as a child’, he wrote in 1920, ‘was Saiyūki; and it is still my favourite. As an allegory I think that there is not so great a masterpiece in the whole of Western literature. Even the renowned Pilgrim’sProgressfalls far short of it. Suikodenwas another of my favourites. I still read that, too. I once learned by heart all the names of the Hundred-and-Eight Heroes of the Suikoden.’ (AidokushonoInshō, Chikuma Shobō 5, 426.)

Their fondness for artistic pursuits meant that when Ryūnosuke decided as a young man on a literary career he encountered no opposition from his family. ‘No-one ever opposed my wish to become a writer,’ he recalled, ‘for my parents and my aunt were very fond of literature. Indeed, 21I might well have been opposed if I had said I wanted to be a businessman or an engineer.’ (BungakusukinoKateikara, Chikuma Shobō 4, 163.)

Not only his love of literature but also that taste for the weird and grotesque that reveals itself in his writings was acquired in childhood. The kusazōshithat were his earliest reading were often illustrated with lurid pictures of goblins and monsters. Tales of ghosts (which were still widely believed in) were commonplace. Ryūnosuke was told by an old woman, who had been his grandparents’ maid, how ‘this singing-teacher was haunted by the vengeful spirit of her husband, or how that old woman was tormented by the ghost of her daughter-in-law’. (Tsuioku, Chikuma Shobō 4, 390.) One result of hearing such stories was that ‘somewhere between dream and reality’ he saw ghosts himself.

He was a sickly child, particularly subject, until the age of nine or so, to convulsions. His sister remembered his being carried to a nearby doctor’s house one night when he was overcome by one of these attacks. He was also nervous and easily frightened. He went in fear of a little shrine the family kept which consisted of a pair of earthenware tanuki (raccoon-dogs, animals credited in Japanese folklore with extraordinary powers) seated on a red cushion. And the family’s Buddhist mortuary tablets, with their blackened gold leaf, were equally terrible objects to him.

In 1897, at the age of five, Ryūnosuke had begun to attend the kindergarten attached to the Kōtō Primary School, which stood next to the Ekōin Temple, just across the street from his home, and in 1898 had moved up into the Primary School 22itself. Long before he left in 1905 he had become a voracious reader, spending much of his time in the city’s public libraries and the commercial lending-libraries around his home. He would often take a packed lunch with him and pass the whole day in the Ōhashi Library at Kudan or the Imperial Library at Ueno.

It was also while he was still at Primary School that his literary creativity first showed itself. When he was about ten, he and a group of classmates began to produce a little magazine which they circulated among their families and friends. Besides writing many of the stories and poems, Ryūnosuke also drew the cover and the illustrations.

In November, 1902, his mother, Fuku, died. Two years later, in 1904, he was formally adopted by Akutagawa Michiaki. That is to say, he relinquished his legal right to succeed to the headship of the Niihara family and his name was transferred to the register of the Akutagawa family. A condition of the adoption was that the name of his Aunt Fuyu, who had been looking after the Niihara household since 1892, and who had borne Toshizō a son, Tokuji, in 1899, was transferred to the Niihara family register.