Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

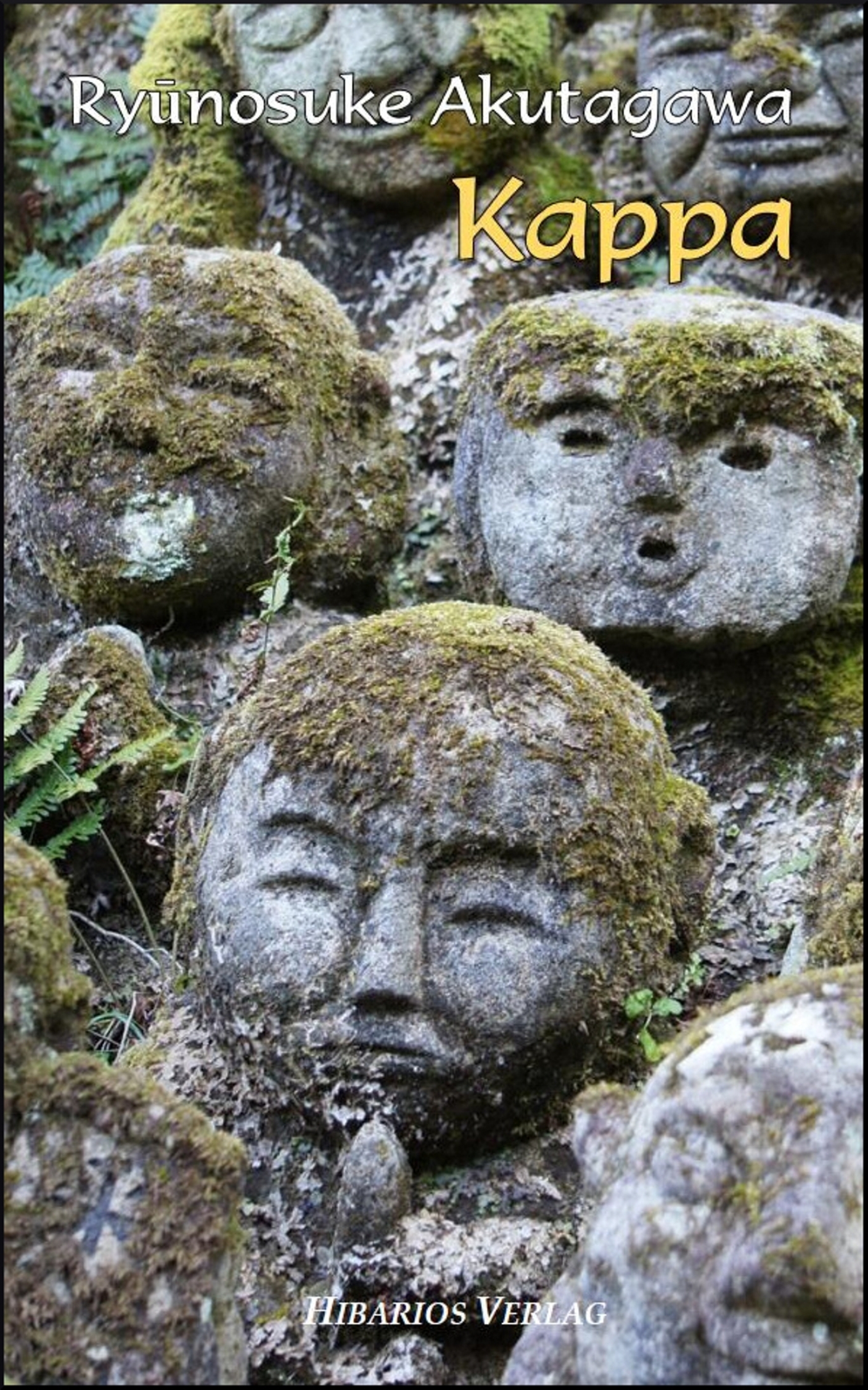

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Pushkin Collection

- Sprache: Englisch

A stylishly original collection of seven newly translated stories from the iconic Japanese writer From a nobleman's court, to the garden of paradise, to a lantern festival in Tokyo, these stories offer dazzling glimpses into moments of madness, murder and obsession. A talented yet spiteful painter is given over to depravity in pursuit of artistic brilliance. In the depth of hell, a robber spies a single spider's thread being lowered towards him. When a body is found in an isolated bamboo grove, a kaleidoscopic account of violence and desire begins to unfold. These are short stories from an unparalleled master of the form. Sublimely crafted and stylishly original, Akutagawa's writing is shot through with a fantastical sensibility. This collection, in a vivid new translation by Bryan Karetnyk, brings together the most essential works from this iconic Japanese writer. Ryūnosuke Akutagawa was one of Japan's leading literary figures in the Taishō period. Regarded as the father of the Japanese short story, he produced over 150 in his short lifetime. Haunted by the fear that he would inherit his mother's madness, Akutagawa suffered from worsening mental health problems towards the end of his life and committed suicide aged 35 by taking an overdose of barbiturates. Bryan Karetnyk is a scholar and translator of Japanese and Russian literature. His recent translations for Pushkin Press include Gaito Gazdanov's The Beggar and Other Stories and Irina Odoevtseva's Isolde.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘One never tires of reading and re-reading his best works. Akutagawa was a born short-story writer’

HARUKI MURAKAMI

‘The quintessential writer of his era’

DAVID PEACE

‘Extravagance and horror are in his work but never in his style, which is always crystal-clear’

JORGE LUIS BORGES

‘He was both traditional and experimental and always compelling and fearless… There is no writer quite like him’

HOWARD NORMAN

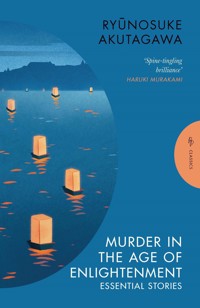

23

MURDER IN THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Essential Stories

RYŪNOSUKE AKUTAGAWA

Translated from the Japanese by Bryan Karetnyk

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The first summer of Shōwa in 1927 found Ryūnosuke Akutagawa at his house in Tokyo’s northern Tabata district. On Saturday 23rd July, a day of lingering heat, the author spent a cheerful luncheon with his wife and three sons before receiving visitors in the afternoon. In the evening he retired to add the finishing touches to a draft of his latest story, a tale of Christ reimagined as a poet, and in the small hours of Sunday, at around one o’clock, as a cooling rain began to fall softly in the garden, he entrusted to his aunt a poem that he had composed during the day. Laced with a characteristically pungent sense of irony, the poem bore the title “Self-Mockery”:

Dewdrop at the tip

Left glinting as twilight fades:

My runny nose.

8 Combining this image of nightfall with an allusion to “The Nose”, an early work that drew the notice of the literary establishment and set Akutagawa firmly on the path to renown, the poem casts a glance at once elegiac and wry over the author’s brief though luminary career. Indeed, those fleeting lines were to prove his jisei no ku, his poem of farewell, for only an hour later, having taken a fatal dose of the barbiturate Veronal, he quit the upstairs study, crept into the futon room and, as he read passages from the Bible, lapsed into unconsciousness and then into death.

When Akutagawa took his life at the age of thirty-five, it put an end to thirteen years of literary endeavour that coincided almost exactly with the reign of the Taishō emperor. Lasting from 1912 until 1926, while the Great War and its aftermath ravaged Europe, and while imperial China and Russia succumbed to revolution, Taishō Japan witnessed a glimmer of democratic liberalism wedged between the Meiji emperor’s austere paternalism and the militaristic nationalism that consumed the early Shōwa years. It was a period of great artistic flourishing, yet it was also a turbulent time—one of political and economic instability as well as great social unrest and catastrophic natural disaster. By its end, an increasing vogue for Marxism had given rise in the cultural sphere to a new trend of 9 proletarian literature. This, and a confessional brand of naturalism, the so-called “I-novel”, stood as the predominant artistic movements of the era. It was against these trends that Akutagawa, whose kaleidoscopic, tiger-bright prose drew insatiably on the Japanese and Chinese classics, on European modernism, and on Buddhist and Christian scripture, emerged as the archetypal bunjin, an artist in the finest and most erudite sense of the word, an aristocrat of letters.

His death, perhaps even more than the passing of the Taishō emperor, came to be regarded as the true end of those volatile years. The Marxists, blind to the horrors lurking in the wings, viewed the event triumphantly as the downfall of bourgeois intellectualism and aestheticism. Others, mindful of the “vague anxiety” of which Akutagawa wrote in his much-publicized suicide note, saw in this fatal act a definitive rejection of that rapidly changing world, poised as it was to take Japan further down the road to territorial expansion and all-out war. Whatever his reasons, whatever our own interpretation, time has secured Akutagawa’s legacy: to this day he rightly endures as that famous and tragic era’s most quintessential writer, and his fiction remains the most dazzling to be produced during those uncertain years.

b.s.k.

10

MURDER IN THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

THE SPIDER’S THREAD

1.

One day, brothers and sisters, Lord Buddha Shakyamuni was strolling alone by the banks of the Lotus Pond in Paradise. The blossoms on the pond were each a perfect white pearl, and from their golden centres wafted unceasingly a wondrous fragrance surpassing all description. It must have been morning in Paradise, brothers and sisters.

By and by, Lord Shakyamuni paused at the edge of the pond, and He looked down through the carpet of lotus leaves to behold the scene below. For you see, directly beneath the Lotus Pond in Paradise lay the lower depths of Hell, and as He peered through the crystalline waters, He could see the River of Three Crossings and the Mountain of Needles as clearly as if He were viewing pictures in a peep box. 14

Soon His eye came to rest on the figure of a man named Kandata, who was writhing around in those hellish depths with all the other sinners. This great robber, this Kandata, had wrought all manner of evil and misdeeds—murder, arson, and more besides. But, for all that, he had, it seemed, performed one single act of kindness in his time. Passing through a deep wood one day, he noticed a tiny spider creeping along the wayside. His instinct was to trample it to death, but, as he raised his foot, he had a sudden change of heart. “No, no,” he thought. “Tiny though this creature is, it’s still a living thing. To take its life on a whim would be too cruel an act, however you look at it.” And so he let it go unharmed.

Lord Shakyamuni recalled, as He looked down on this scene of Hell, that Kandata had saved that spider, and so He decided to reward this singular good deed by rescuing the man from Hell if He could. As chance would have it, He turned to see a heavenly spider spinning a beautiful silver thread atop a lotus leaf with the brilliance of kingfisher jade. Taking the spider’s thread carefully in His hand, Lord Shakyamuni lowered it among the pearl-white lotus blossoms, straight down into the far-distant depths of Hell. 15

2.

There, in the Pond of Blood at the very pit of Hell, Kandata and his fellow sinners kept floating up and sinking back down again. Pitch darkness reigned wherever the eye roamed. The only thing to pierce it was the faint glint of a needle on the awe-inspiring Mountain of Needles—and that only heightened the sense of despair. All around hung a sepulchral silence, and the only sound to break it was the occasional sighing of a sinner. For you see, brothers and sisters, having fallen as far as this, they had already been so wearied by the many tortures of Hell that they no longer had the strength to cry out. And so, even Kandata, great robber though he was, could only thrash around like a dying frog as he choked on the blood of the Pond.

And what should happen then but that Kandata should lift his head up to the sky above the Pond of Blood and see there, amid the pitch-black stillness, a glimmering silver thread gliding stealthily down from the high, high heavens. When Kandata saw it coming straight towards him, he clapped his hands with joy. Surely, if he could just grab hold of it, he could climb his way out of Hell. Perhaps, with a bit of luck, he could even make it all the way to Paradise. No more 16 then would he be driven up the Mountain of Needles or plunged down into the Pond of Blood.

Having formulated his plan, he gripped the spider’s thread in both hands and began pulling himself up, higher and higher, with all his might. For the great robber he had once been, this skill in climbing was practically second nature.

However, the journey from Hell to Paradise is one of untold thousands of leagues, and so no matter how Kandata tried, it was no easy task to escape. Up and up he climbed until eventually even he was overcome by weariness and could haul himself no further. He had no choice but to rest awhile, and, as he clung to the thread, he looked down into the depths far below.

Kandata’s heroic climb had been worth the effort; the Pond of Blood where he had languished only a short time ago now lay hidden in the black depths. What was more, even the faint glint of the awe-inspiring Mountain of Needles was now far beneath his feet. At this rate, climbing his way out of Hell might prove easier than he had imagined, and so, clasping both hands around the spider’s thread, Kandata laughed aloud as he had not done in the many years since coming to this place. “I did it! I’m saved!” 17

Just then, however, he noticed far below an innumerable company of sinners scrambling up after him, higher and higher, like a column of ants. The sight struck him with such shock and terror that for a moment all he could do was move his eyes and let his mouth hang open like a fool’s. It seemed as if the delicate thread would snap from his weight alone—how could it possibly bear that of so many others? If it were to break midway, then he—he himself!—would go plummeting back down into the Hell that he had taken such pains to escape. How horrible it would be! But still, an unbroken chain of sinners kept swarming up the fragile, gleaming thread from the very depths of the pitch-dark Pond of Blood. They were coming in their hundreds, in their thousands! He had to do something right away, or else the thread would snap.

“Now listen here, you sinners!” Kandata roared at them. “This spider’s thread is mine! Who said you could climb up it? Go back! Go back!”

That was the moment when it happened, brothers and sisters. The spider’s thread, which until then had been perfectly sturdy, lashed the air, sealing his fate. It broke just at the point where Kandata had been hanging from it. Before he could even cry out, he plunged down, whirling like a spinning top, rushing headlong into the black depths below. 18

The only thing left behind was the short end of the spider’s thread, dangling down from Paradise, glittering faintly in a moonless, starless sky.

3.

As he stood on the bank of the Lotus Pond in Paradise, Lord Buddha Shakyamuni followed everything closely from start to finish. And when at last Kandata sank like a stone into the depths of the Pond of Blood, He resumed his stroll, His countenance now tinged with sorrow. Kandata had meant to save himself alone and, as punishment for his lack of compassion, had fallen back into Hell. How terribly shameful it all must have seemed, brothers and sisters, in the eyes of Lord Shakyamuni.

And yet the lotuses of the Lotus Pond were not in the least perturbed by any of this. Those pearl-white flowers swayed their heads by the feet of Lord Shakyamuni, and from their golden centres wafted unceasingly a wondrous fragrance surpassing all description. It must have been close to noon in Paradise.

IN A GROVE

THE TESTIMONY OF A WOODCUTTER UNDER QUESTIONING BY THE MAGISTRATE

That’s right, your honour. It was I who found the body. This morning I went out as usual to cut cedar in the mountains overlooking the village, when I came across the body lying in a shady grove. The exact location? A few hundred yards from the Yamashina stage road. An out-of-the-way spot with a few scrub cedars dotted among the bamboo.

The body was lying flat out on its back, dressed in a pale-blue silk robe, and it was wearing one of those elegant peaked black hats they wear in the capital. There was only one stab wound, but the blade had gone straight through his chest. The leaves of bamboo scattered on the ground around the body were stained dark red with blood. No, Your Honour, the bleeding had stopped. The wound looked dry. Yes, and there 20was a horsefly feeding on it so intently that it didn’t even hear me approach.

Did I see a sword or the like? No, not a thing, Your Honour. Just a length of rope by the cedar next to the body. And—that’s right, yes, there was a comb there, too. Just those two items. But the grass and the bamboo leaves had been so trampled down that he must have put up a terrific fight before they killed him. How’s that, Your Honour? A horse? No, a horse could never have made it into a place like that. There’s only thicket between there and the road.

THE TESTIMONY OF AN ITINERANT PRIEST UNDER QUESTIONING BY THE MAGISTRATE

I’m sure I passed the man yesterday, Your Honour. Yesterday at—well, it must have been about noon. Where? It was on the road from Ōsaka Mountain to Yamashina. He was heading towards the checkpoint together with a woman on horseback. She was wearing a wide-brimmed hat with a long veil, so I didn’t see her face. All I could see was the colour of her robes—a sort of vermilion with a dark teal lining. The horse was a palomino—and, if I remember rightly, its mane was clipped. How tall was it? Taller than most, but 21only by a hand. Then again, Your Honour, I’m only a priest and don’t know much about these things. The man? Well, he wore a long sword and carried a bow and arrows. I can still see that black-lacquered quiver of his: it must have had more than twenty arrows in it.

Even in my wildest dreams, I should never have imagined that he would meet such a fate. Truly, man’s life is evanescent: like the morning dew or a flash of lightning. Oh, what a wretched business. Words desert me.

THE TESTIMONY OF A POLICEMAN UNDER QUESTIONING BY THE MAGISTRATE

The man I arrested, Your Honour? He’s without a doubt the notorious bandit Tajōmaru. Granted, when I apprehended him, he’d been thrown by his horse. I found him groaning on the stone bridge at Awataguchi. The time, Your Honour? It was last night, during the first watch. He was wearing the same dark-blue robe and carrying the same embossed sword as when I tried to arrest him last time. Only on this occasion, as you can see, he’s somehow managed to get his hands on a bow and arrow. Is that so, Your Honour? Property of the deceased? Well then, Tajōmaru must be the culprit. A bow bound with leather straps, a lacquered quiver and 22seventeen arrows fletched with hawk’s feathers—they must all have been the victim’s. Just so, Your Honour. As you say, a palomino horse with a clipped mane. He certainly got what was coming to him, being thrown like that. I found the animal a little past the bridge, grazing by the roadside and trailing its long reins.

Of all the bandits prowling about the capital, this Tajōmaru certainly likes his women. Just last autumn, at the Toribe Temple, two worshippers—a palace servant and her child—were found murdered in the hills behind the statue of Binzuru. Everybody suspected that the crime was his doing. If he did indeed kill the man, then there’s no telling what he might have done to that woman on the horse. May it please Your Honour to look into this matter, too.

THE TESTIMONY OF AN OLD WOMAN UNDER QUESTIONING BY THE MAGISTRATE

Yes, that is the body of the man who married my daughter. But he wasn’t from the capital, Your Honour. He was a samurai serving in the Wakasa provincial office. His name was Kanazawa no Takehiro and he was twenty-six years old. No, Your Honour, he had such a gentle nature that I can’t imagine anyone holding a grudge against him. 23

My daughter, Your Honour? Her name is Masago and she is nineteen years old. She’s as bold as any man, although the only one she’s ever known is Takehiro. She has a small oval face with a dark complexion, and a mole at the inner corner of her left eye.

Takehiro left for Wakasa with my daughter yesterday, but what cruel twist of fate could have led to this? There’s nothing I can do for my son-in-law now, but what has become of my daughter? I’m sick with worry for her. Please, Your Honour, I beg of you: leave no stone unturned to find her. Oh, how I hate that bandit—that, that Tajōmaru. Not only my son-in-law but my daughter … [At this point her words broke off, drowned by a flood of tears.]

* * *

TAJŌMARU’S CONFESSION

Yes, I killed him all right. But I didn’t kill the woman. How should I know where she’s gone? I don’t know any more than you. Now, wait here—you can torture me all you like, but I can’t very well tell you what I don’t know. Besides, I’m no coward. I’m hardly likely to hide anything from you under the circumstances. 24

I met the couple yesterday, a little after noon. The moment I set eyes on them, a gust of wind lifted her veil and I caught a glimpse of her face. Just a glimpse, mind you—for no sooner had I seen it than the veil covered it again. Maybe that’s why she seemed so perfect—a bodhisattva of a woman. Anyway, I decided there and then that I had to have her, even if it meant killing the man.

Oh, come off it. Killing a man isn’t as difficult as you people seem to think it is. At any rate, if you want to rob a man of his woman, it’s only natural that you’re going to have to kill him. Only, when I do it, I do it with a sword. People like you don’t use swords. You gentlemen kill with power, with money, sometimes with words alone—all on the pretence of doing a man a favour. True enough, no blood is shed. He might even live well. But you’ve killed him all the same. It’s hard to say whose sin is greater—yours or mine. [An ironic smile.]

Of course, if you can rob a man of his woman without killing him, so much the better. In fact, that’s what I was hoping to do yesterday. But it would have been impossible on the Yamashina road, so I hatched a plan to lure them into the hills.

It was easy. I fell in with them and made up some cock-and-bull story about finding an old burial mound in the hills. When I opened it, I said, it was full of 25swords and mirrors and all kinds of riches and, to stop anyone else from finding it, I’d buried it all in a shady grove on the far side of the mountain. I told them I was willing to sell it cheap to the right buyer. The man grew more taken with my little tale by the minute. Then—oh, isn’t greed a terrible thing? Not even half an hour later, they were leading their horse up the mountain trail with me.

When we reached the spot, I told them that the treasure was buried in the grove and invited them to take a look at it. The man was so consumed by greed that he couldn’t refuse, but the woman said she’d wait on the horse. After all, she could see how densely overgrown the place was. As a matter of fact, that was just how I’d planned it. So I led the man into the grove, leaving her behind.

The grove is only bamboo at first. But then, after fifty yards or so, you come to a clearing with some cedars—the perfect spot for what I had in mind. As I pushed on, clearing my way through the thicket, I spouted some nonsense about the treasure being buried under one of the trees. No sooner had the words been spoken than he made a run for the scrawny cedars we could see up ahead. The bamboo soon thinned out and we came to a spot where several cedars stood in a row. I grabbed him there and then 26and wrestled him to the ground. I could tell he was strong—and what’s more, he had a sword—but I had the element of surprise. He didn’t stand a chance. I had him tied to one of the trees in no time. Where did I get the rope? A piece of rope’s a godsend to a bandit—you never know when you might have to scale a wall. I always carry one on me. Naturally, to stop him calling out, I stuffed his mouth full of bamboo leaves. He didn’t give me any more trouble.

Once I’d finished with him, I went to tell the woman that her husband had suddenly fallen ill and wouldn’t she come and take a look at him. Need I say that was another master stroke? She took off her hat and let me lead her by the hand into the grove. But as soon as she saw him tied to the tree, she drew a dagger from her breast. I never saw a woman so fierce. If I hadn’t been on my guard, she might have got me right in the stomach. I managed to dodge her, but the way she kept slashing at me … She could have done some real damage. Still, I am Tajōmaru. One way or another, I eventually managed to knock the dagger out of her hand without having to draw my sword. Even the most spirited woman is nothing without a weapon. At last I could get my hands on her without having to take the man’s life.

That’s right—without taking the man’s life. I didn’t mean to kill him after all that. But as I was about to 27flee the grove, leaving the woman to her tears, she suddenly clung to my arm like one possessed. Between sobs she wailed, “Either you die or he dies … One of you must … To have two men see and know my shame is a fate worse than death …” As she gasped for breath, she said, “I’ll belong to whichever one of you survives …” I was seized by a wild desire to kill him on the spot. [Grim excitement.]

To hear all this, you gentlemen must think me far crueller than yourselves. But that’s because you didn’t see the look on her face, because you didn’t see the fire that flashed in her eyes. When those eyes met mine, I knew I would make her my wife, even if the god of thunder struck me down. To make her my wife—this was my sole thought and desire. I know what you gentlemen are thinking—and no, it wasn’t lust. If lust was all I felt for her, then surely I wouldn’t have hesitated to knock her down and flee the scene. Nor would my sword have been smeared with his blood. But the moment I saw those eyes of hers in that shady grove, I resolved not to leave there until he was dead.

Still, I couldn’t bring myself to kill him in this cowardly way, and so I untied the rope and challenged him to a sword fight. (The rope I threw aside is the one that was found by the trunk of the cedar.) The man looked furious as he drew his mighty sword, and 28without so much as a word he launched himself at me in a blind rage. I needn’t tell you what the outcome of the fight was. Not until the twenty-third strike did my sword pierce his breast. The twenty-third—please, remember this. Even now, I’m filled with admiration for this fact alone. No other man in the world has lasted even twenty blows with Tajōmaru. [A cheerful laugh.]

As he fell, I lowered my bloodstained sword and turned to the woman. But she was nowhere to be seen. I looked for her among the cedars, but even the bamboo leaves on the ground showed no sign that she’d ever been there. I pricked up my ears, but all I could hear was the death rattle coming from the man’s throat.

Perhaps she ran to call for help as soon as the fight began. Weighing the possibility, I began to fear for my life. I grabbed the man’s sword along with his bow and arrows and headed straight for the mountain road. There I found the woman’s horse still grazing quietly. I’d only waste my breath telling you what happened after that. As for the sword, I threw it away before I reached the capital.

There you have it. So do your worst. I always knew my neck would end up hanging from a tree someday. [A defiant attitude.] 29

THE PENITENT CONFESSION OF A WOMAN AT THE KIYOMIZU TEMPLE

… After the man in the dark-blue robe had his way with me, he turned to my husband, who was still tied up, and taunted him with laughter. How humiliating it must have been for him! But no matter how he squirmed or struggled, the knots in the rope that bound him only cut deeper into his flesh. Stumbling, I ran to his side. Or, no—I tried to run to him, but the man struck me down with a single blow. That was when it happened. That was when I saw the indescribable gleam in my husband’s eyes. Indescribable, it was … Even now, the very thought of those eyes is enough to make me shudder. Though my husband couldn’t utter a word, in that instant his eyes told me everything. But it was neither anger nor sorrow that I saw flash in them … only a cold glimmer of loathing. Struck more by the look in his eyes than by the thief’s kick, I let out a cry and fell unconscious.

When at last I regained consciousness, the man in the dark-blue robe was gone. Only my husband was left, still tied to the cedar. With difficulty I raised myself up from the carpet of bamboo leaves and looked into my husband’s face, but the expression in his eyes was the same as before—that same cold loathing and 30unconcealed hatred. How shall I describe what I felt then? Shame, sorrow, anger? I got to my feet and, still reeling, staggered over to him.