Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Banipal Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

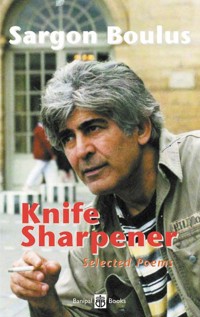

Knife Sharpener – Selected Poems is a posthumous commemoration and celebration of Sargon Boulus, in a collection of poems, written between 1991 and 2007 that he translated himself, together with an essay, "Poetry and Memory", written a few months before he died in October 2007. With a Foreword by Adonis and an Introduction by Dublin poet and publisher Pat Boran, the volume includes nine pages of photographs and tributes from fellow poets and writers Saadi Youssef, Ounsi El-Hage, Amjad Nasser, Abbas Beydhoun, Abdo Wazen, Fadhil al-Azzawi, Kadhim Jihad Hassan, Khalid al-Maaly, and Elias Khoury, assembled and translated by fellow Iraqi poet Sinan Antoon, who described his death as leaving "a gaping wound in the heart of modern Arabic poetry". "Sargon seemed to feel also the even greater, historical weight of conflicts, tensions, misunderstandings and oppressions of the spirit, as if his poems came through his own time and language but from somewhere else." – Pat Boran Sargon Boulus was unusually influential among young Arab poets, who "found in him the father who refused to practise his patriarchy and a poet who always renewed himself in his rebellion against rhetoric . . ." Abdo Wazen

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 83

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SARGON BOULUS

Sargon Boulus (1944–2007) remains one of the best-known and most influential of contemporary Arab poets. Born into an Assyrian Iraqi family, and growing up in Al-Habbaniyah, Kirkuk and Baghdad, he started publishing his own work in 1961 in the ground-breaking Shi’r [Poetry] magazine in Beirut. After settling in San Francisco in the late 1960s, he became an unstoppable translator of English-language modern poets into Arabic and dedicated his life to reading, writing and translating poetry, every so often making forays to Europe to meet up with fellow exiles and perform at festivals. His untimely death, in Berlin in October 2007 at the aged of 63, left “a gaping wound in the heart of modern Arabic poetry”.

He has six poetry collections of his own work and has translated numerous British and American poets into Arabic. He has two bilingual collections in Arabic and German, one of poetry and one of short stories, he also co-authored Legenden und Staub, with Bosnian author Safeta Obhodjas (2002). He was a contributing editor, and later a consulting editor, for Banipal from its first issue in February 1998.

Sargon Boulus played an invaluable role in introducing to Arab poets and readers major modern English-language poets, including Ezra Pound, W. H. Auden, W. S. Merwin, Ted Hughes, William Carlos Williams, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Sylvia Plath, Robert Duncan, John Ashbury, Robert Bly, Anne Sexton, John Logan and Michael Ondaatje, as well as other poets such as Rilke, Neruda, Vasko Popa and Ho Chi Min.

Sargon started assembling this collection, Knife Sharpener, whose title he chose, in the months before he died. It is published now, in an extended form, as a posthumous commemoration and celebration of Sargon Boulus, bringing together for the first time all the poems, written between 1991 and 2007, that he translated himself, together with an essay, “Poetry and Memory”, written especially for this volume.

First published in the UK by Banipal Books, London 2009

Copyright © 2007 Sargon Boulus

Translation copyright © 2009 Banipal Publishing

Introduction copyright © 2008 Pat Boran.

All photographs © Banipal Publishing

The poems in this collection were translated from the original Arabic by the author from his collections Hamil al-Fanous fi Lail el-Dhi’ab (1996), Idha Kunta Na’iman fi Markabi Nooh (1998), and Al-Awal wal-Tali (2000) and from unpublished poems

The moral right of Sargon Boulus to be identified as the author and the translator of these works has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher

A CIP record for this book is available in the British Library

ISBN 978-0-9549666-7-6

E-ISBN: 978-1-913043-47-6

Banipal Books

1 Gough Square, LONDON EC4A 3DE, UKwww.banipal.co.uk/banipal_books

Set in BemboPrinted and bound in the UK

Sargon Boulus1944–2007

In commemoration and celebration

CONTENTS

Foreword by Adonis

Introduction by Pat Boran

Poetry and Memory by Sargon Boulus

The Poems

How Oriental Singing was Born

Meknes, Morocco

The Siege

He Who Goes to the Place

The Borders

Incident in a Mountain Village

In Praise of Encounters

In the Midst of Giving Birth

The Midwife’s Hands

This Road Alone

A Conversation with a Painter in New York after the Towers Fell

The Corpse

This Master who …

Master

We Heard the Man

A Song for the One who will Walk to the End of the Century

Who Knows the Story

You, the Story-teller. These: Your Days.

The Story will be Told

If the Words should Live

The Mystery of Words

The Skylight

Tea with Mouayed al-Rawi in a Turkish Café in Berlin after the Wall came down

Entries for a Possible Poem

A Dream of Childhood

A Boy Against the Wall

Butterfly Dream

The Face

Witnesses on the Shore

Notes from a Traveller

Dimensions

Witness

Widow Maker, Mother of Woes

The Scorpion in the Orchard

The Executioner’s Feast

War Child

Hulagu the Hun’s Exultation

Knife Sharpener

The Saint’s Mountain

Execution of the Falcon

A Few Moments in the Garden

The Apaches

The Letter Arrived

The Man Fell

Legacy with a Taste of Dust

He Who Comes

The Pouch of Dust

The Ziggurat Builders

The Legend of Al-Sayyab and the Silt

O Player in the Shadows

A Key to the House

News about No one

Remarks to Sindbad from the Old Man of the Sea

Invocations Before Sailing

Photographs by Samuel Shimon

Tributes

Introduced and Translated by Sinan Antoon

Saadi Youssef – The Only Iraqi Poet

Elias Khoury – The Sargonian poem

Ounsi el-Hage – Iraqis are epic people

Amjad Nasser – The Assyrian’s Boat

Abdo Wazen – The vagabond poet

Abbas Beydhoun – His overwhelming legacy

Fadhil al-Azzawi – To Sargon, poetry was something akin to magic

Kadhim Jihad Hassan – An immense freedom

Khalid al-Maaly – He shines in his poems

Afterword by Margaret Obank

Acknowledgements

Sargon Boulus at James Joyce’s statue, Dublin

Foreword

HIGH AND VERTICAL

As it is, not as metre or rhyme. This is how Sargon Boulus views poetic writing and how he practises it. Writing, for him, is another existence within existence. Thus he only encounters himself as he encounters the world. When he avoids, moves away, and secludes himself, it is for one purpose: to complete the distance required for this encounter which allows him to see well and to know how to penetrate and look ahead.

He does not engage in polemics. Let what is good be good for its people. And let what is evil be evil for its people. Let those who want to clash, clash. He prefers to stay in the light. In the navel of the thing, high and vertical. Values are swings and light is beyond all directions. What is “the message”?

Water seeps through and goes deep.

The air touches the rose and the thorn with the same hand.

The wing is the closest sibling to the horizon.

There is no separation between reality and what is beyond it:

Imagination, for Sargon Boulus, is mixed, kneaded with material as if it is another body in his body.

Sargon’s poetry asks me.

And that is why I love him.

Adonis

Paris, 20 October 2007

Adonis wrote this Foreword to Knife Sharpener just two days before Sargon Boulus died

INTRODUCTION

There are not many people one can truly call a poet – in the sense of an individual whose entire life seems dedicated to, even composed by, poetry: but Sargon Boulus was one of them. Like a lot of people, from the moment I first met Sargon, at the Dublin Writers Festival in 2003 for a celebration of contemporary Arab writing, I felt I was in the presence of someone truly significant. For here was a poet who was clearly deeply wounded by the recent events in his homeland of Iraq, but not just those recent events: like all great poets Sargon seemed to feel also the even greater, historical weight of conflicts, tensions, misunderstandings and oppressions of the spirit, as if his poems came through his own time and language but from somewhere else. No doubt this was in part due to the fact that he wrote in Arabic, a language which offered (if not demanded) historical coherence and continuity in ways I could only imagine.

The audience at that Dublin Writers Festival event was, no doubt like myself, expecting a certain amount of political observation. This was in mid June: three months earlier the US and its allies had commenced “the liberation of Iraq”. And yet what we heard from Boulus and his fellow writers – Samuel Shimon, Hassouna Mosbahi and Maram Al-Massri, introduced by Banipal’s Margaret Obank – was in general that much longer view of history, that much longer view of the writer’s role in the world. This seemed particularly the case with Sargon.

W B Yeats’s notion about the relationship between poetry and politics has seldom seen clearer expression than in the poetry of Sargon Boulus: “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry,” wrote Yeats, apparently presenting an either/or choice that has caused many a poet to stumble. Not a political poet, certainly not trusting of the unexamined impulse to make political verse, nevertheless in the words of Saadi Youssef, Sargon Boulus “stood against the occupation of Iraq because poets must be against occupation”.

Of course Boulus could never have been a political poet, even if that had been his goal. For, as he says himself in this volume, “when I write, I am actually remembering, not the past itself, not a person or a place, a scene or sound or song, but first and foremost I am remembering words”. This withdrawal from agreed, shared, external experience into the zone of the imagination is unlikely to go well with any purely political movement; but it is also interesting to note that Sargon’s approach to poetry is not directed exclusively to self, is not simply a diary in verse of the poet’s inner life. By nailing his colours to words – the building blocks of experience – he avoids the either/or dichotomy confronted by Yeats and finds not a middle but a third way, a path whose ground seems sometimes both, sometimes neither but on which the poet cannot fail to tread. As some of the best of Neruda’s “political” poetry came from his realization that the world of objects carried the history of those who made them (“The contact these objects have had with man and earth may serve as a valuable lesson to a tortured lyric poet”), so too does Sargon find a meaningful connection between the lyric and personal and the wider historical imperatives. As he says himself, “I believe that any given language contains all the memory traces of the communities that contributed to it. For a poet, nothing is lost.”

And the poet who lives during wartime and is “beseiged by the cries / of his tribe as he wanders / among the bones / and walks through the ruins / of his city”, what is there for him to do? He can only dream