Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Huia Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Tokyo is a humming backdrop to an array of outsiders: a young woman arrives in Japan to work as a stripper, the manager of a love hotel has a sleazy plan, a ghost wanders Harajuku, and a woman returns to New Zealand on the saddest journey of her life. Meanwhile, expats trip on mushrooms in Bali, love blooms and sours on Auckland's wild west coast, and workers at a peep show have a brush with a serial killer. The Japanese secular city of salarymen, sex workers and schoolgirls is juxtaposed with the New Zealand setting of rongoā healers, lone men and rural matriarchs. Linked through recurring characters and themes of identity: expat versus indigenous, gender, mother/maiden/crone, these haunting stories from the margins of Japan and New Zealand explore teen suicide, relationships, romantic disappointment, the male gaze, a world of hostessing and exotic dancing, and hedonism of the expat bubble.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2022 by Huia Publishers39 Pipitea Street, PO Box 12280Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealandwww.huia.co.nz

ISBN 978-1-77550-697-3 (print)ISBN 978-1-77550-745-1 (ebook)

Copyright © Colleen Maria Lenihan 2022

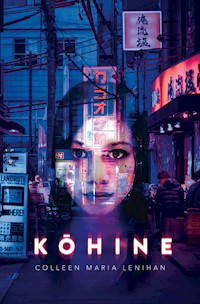

Front Cover:Portrait photography copyright © Colleen Maria Lenihan 2022City photograph courtesy Greg Jeanneau/Unsplash.com

Interior photography copyright © Colleen Maria Lenihan 2022Back cover city photography courtesy of Orlie K/Unsplash.com

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Published with the support of the

Ebook conversion 2022 by meBooks

for Monique

E kore au e ngaro

he kākano i ruia mai

i Rangiātea

Contents

Gnossienne No. 1

Cherry Blossom Girl

Ruru

Nerissa

Little Miss Paranoid

Paradise

Autumn Feeling

Spirit House

Idol

Love Hotel

The Storm

Mama

Leaping-off Place I

The Void

Just Holden Together

Private Dancer

Directions

Pepe Tuna

Sushi Train

Tama

The Actor

Sista

Leaping-off Place II

Acknowledgements

Gnossienne No. 1

Slabs of sunlight fall, dust motes float like amoeba across the room. Books, sheet music and vinyl records line the walls, cover the tatami in wooden cases and teeter in precarious stacks. In the tokonoma, a pair of hand-tinted photographs hang above a black lacquer shrine.

Yuki is playing a sensual, jazzy arrangement. It is only her second attempt, so you feel good-natured and forbearing about her fumbles on the keys. Finally, she gets a feel for the piece. She closes her eyes like a torch singer and launches into the chorus, her surprisingly husky voice plaintive.

You usually detest J-pop, but you have to admit this piece by Nakashima Mika is quite charming. You have been teaching Yuki piano since she was ten, when her family first moved to Tokyo. Her mother called on you with a gift of green tea from Kyoto, saying she’d heard you were the best piano teacher in Shibuya-ku and would you please look upon her favourably and take her Yuki on?

The winter sun rings Yuki’s glossy black bob; her shoulders rise and fall. As always, she is in school uniform: white blouse, check skirt fashionably shortened, baggy white socks. She sings the last line, which pleads in English:

‘Please … please …’

The notes hang in the air. You walk over to her, clapping.

‘Subarashii, Yuki-chan.’

She shakes her head.

‘Ie, ie, Hamasaki-sensei. So many mistakes.’

‘Such feeling though.’

‘My best friend sings this at karaoke. She lives in your building.’

Yuki slings her schoolbag over her shoulder, bows and says goodbye. As she walks out the door, you take in her long Bambi legs, the swing of her hips … this is a young girl about to blossom. You feel pangs of moe. Not in a lecherous way. More a protective wonder.

The ‘Super View’ Odoriko train looks like a Shinkansen but has wider windows and moves at a far more leisurely pace. Sitting on the left for the views of the Pacific below, you see the island of Ōshima in the distance. Your surfboard has been sent ahead to the guesthouse you always stay at in Shimoda. A full wetsuit with booties and a hood is packed in your canvas duffle bag, ready for the chilly typhoon swells due to roll in from the north-east. The train attendant rattles past with her cart. You order a Kirin beer to have with the bento box you purchased at the station. Shōgayaki is your favourite, and you devour the juicy slices of pork. The family seated in front of you are at the window. The father points out the fishing boats to his little girl. Her chubby hand traces circles in the air. You think about Natalie, the woman who had once loved you, and imagine what you’d say to her if she was sitting next to you in the first-class car.

‘What’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?’

You already knew your answer. A volcano erupting in Hawai‘i. Natalie, with the heart-shaped face and cropped blonde hair, would think for a second, then say:

‘You.’

A cab deposits you outside a white weatherboard guesthouse. There are two houses side by side and double storeyed: four units. A faded sign says ‘AZUL BEACH SIDE CONDOMINIUM’. The owner, Abe-san, an old surfer in worn tie-dye and camo Crocs, greets you. He gives you the key to your usual room on the second floor, the one with the framed print of the Matterhorn. Your surfboard is waiting for you at the door. You remember when Natalie kicked off her Mary-Janes and rushed in to jump up and down on the bed like a child. You’d joined her, until you both fell back on the pillows, breathless.

You fix yourself a Jack and Coke and smoke on the balcony until dark.

The next day you are up early at what Natalie used to call ‘Dawn’s crack’. You had hoped dating an Australian would improve your English, but it’s mada sugoku heta. You brew coffee and drink it on the balcony. Your eyes scan the swell. In the half-light, sand, sky and sea are strips of texture, like a grainy black-and-white photo.

The beach is deserted. It is closed at this time of year. You are breaking the rules, but the locals don’t care about the few die-hard surfers like yourself who still head out in winter. Izu people are relaxed like that. It is a relief to be out of Tokyo, away from the sea of people and crushing weight of collective obligation. You amble onto the beach with your board and take in long, deep breaths. The sky is bone white and the ocean is grey. The spare desolation exhilarates you, and you break into a jog. The freezing water shocks you awake. You must keep moving so the cold doesn’t overtake your senses and force you back to shore. You jump on the board and paddle out.

Flat water. A lull. Out there amongst it all, you are totally alone. Scraps of fog cling to the ragged coast behind you, and you catch spooky, sharky feelings. You negotiate with the ocean: don’t drown me, or give me a beating. I don’t need any trouble. Black lumps form in the distance. You paddle up and down the beach, in search of the perfect position to catch a wave when the set rolls in.

You sigh as you ease yourself into the steaming waters of the onsen. For a moment you are the luckiest man in the world. Eyeing the ‘TATTOOS PROHIBITED’ sign, you drape a wash cloth over yourself to conceal the tiny inking on your inner forearm. You and Natalie had got each other’s initials on a bender in Thailand. The next day, she’d laughed and said, ‘Winona Forever!’ She made you want to be gaijin too sometimes. You wouldn’t have to think so much before you opened your mouth. You wish she was up to her pale neck in the cypress tub with you, green eyes shining. They changed colour according to the weather and her mood. The opalescent chalkiness of the mineral pool would probably make them a light grey green. Where is she? What is she doing now? She who was once the centre of your life is now an unknowable stranger. You resolve to banish Natalie from your mind, once and for all. You block her on every platform and delete all evidence of the relationship from your phone.

The routine for the next four days is this: up at Dawn’s crack, coffee and cigarette, surf until your teeth chatter, soak in healing waters, fall asleep in massage chair, pad back to your room in yukata and slippers, re-read Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, drink Jakku Coku on the deck until midnight.

* * *

You catch the train back to Tokyo, hungry for your favourite ramen, icy cold pints at your local izakaya, your piano. You look forward to seeing your students and asking them about their holidays. You alight at Daikanyama Station. It’s nice out. Young fashionable couples stroll past looking pleased with themselves and their choices. They throng the outdoor café. You smile at a black French bulldog being pushed around in a buggy. It smiles back. Your apartment block is nearby, just a minute away. You stop by Lawson’s to get a tamago sando and a can of hot Royal Milk Tea. A handwritten note is taped to your door.

Hamasaki-sanPlease contact Shibuya Police Station03-3498-0110

Huh? You read it again. Your heart starts to pound. You grab the note, unlock the door, dump your bag in the genkan. Have you been robbed? No broken windows. You scan for signs of a break-in, but your stacks and piles appear undisturbed. You dial the number on the note, and a woman puts you through to a Detective Furiyama.

‘On January first, a gaijin living on the fourth floor of your building, Daikanyama Royal Copo, jumped from their balcony and landed in your backyard. Police and ambulance workers had to enter while you were away. We are sorry for the trouble.’

‘Eh! Hontō desu ka? Are they okay?’

‘She died. A high school student. It is most regrettable.’

You hang up. Your hands tremble as you light a cigarette. You look upon the picture of your grandmother; an attempt to draw comfort from her serene countenance. You step into the yard and see the wooden fence has been knocked askew. A crow has lit on it, so black it is almost blue. It watches as you see the blood on the concrete tiles. You look up to see the balcony the girl jumped from. It’s higher than you expect.

You light several sticks of incense with your grandfather’s silver Zippo. Thick white smoke curls up into the cold January air, releasing agarwood and benzoin. Press your palms together and bow. You think of this girl and her parents. You think of your parents. You think of their parents. You think of your childhood pet, Mochi. You think of Kano-sensei, your piano teacher. You think of your student, Yuki-chan. You think of Natalie.

The incense clings to your clothes and follows you inside. You search through the piles of sheet music to find a piece by Satie and sit down at the piano. His unusual notation instructs you to perform ‘monotonously and whitely’, ‘very shiningly’ and ‘from afar’. You play and the melody slips out of the room into the yard, whirls for a while with the drifts of smoke, and then floats up, up, up into the ether.

Cherry Blossom Girl

At 5 a.m., a phone call:

‘Where are you?’

The taxi came to a halt outside the Shibuya Police Station. Maia noticed what a lovely morning it was. Crisp blue skies, everything blanketed in snow. New Year’s Day was always the quietest day of the year in Tokyo.

She ran into the police station, footsteps clattering in the hush, to an elevator that took her underground to a room at the end of a dim corridor, and there in the gloom, three policemen bowed deeply to a form draped in white. She pulled back the sheet. The tongue protruded slightly, bitten hard with even white teeth. Maia clung to Aria and felt how cold she was, small breasts like stones against her chest. Sixteen years old, forever. Her knees gave way, and one of the cops began to weep.

Maia set to the task of ringing people around the world and ruining their New Year.

‘My poor mother,’ she said after the most difficult phone call.

‘Poor Maia,’ said Hiromi, perched at the foot of Maia’s bed.

Maia drank cans of beer and shook under the covers. She stared at Aria’s picture on her gaijin card. Dark eyes gazed back at her with an amused air, like she was about to say something funny.

In the night, remnants of Maia’s Catholic upbringing kicked in. She recited the Angelus, Hail Marys over and over, like a rosary.

‘Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen.’

Hiromi drove Maia out to the funeral home on the outskirts of the city. A fleet of hearses were parked outside with ornate shrines grafted on to their roofs. They looked like mobile Buddhist temples. Staff in black wore ashy make-up, which made them look dead themselves. Hiromi dealt with the funeral director, who constantly mopped his brow and sucked air through his teeth. The death of a foreigner was a lot of trouble, especially at this time of year. With a pained expression, he insisted that Maia view the body before they undertook any embalming.

‘No, I will do it,’ said Hiromi, reasoning that Maia shouldn’t see Aria again until she was surrounded by her family in New Zealand. Maia didn’t know what was best. The logistics of repatriating a body were overwhelming. There were so many decisions.

Hiromi came back to the car afterwards, green from the smell of formaldehyde.

‘They dressed Aria in a beautiful kimono,’ she said, and touched Maia lightly on the arm before turning to throw up on the edge of the carpark.

Maia carefully placed the framed photograph that she had been clutching to her chest like a lifebuoy in the seat pocket in front of her so that Aria was facing out. Please don’t anyone speak to me. The instant the thought arose, the woman sitting next to her said, ‘Who is that? She is very pretty.’

‘My daughter,’ Maia said.

‘Where is she?’

‘She’s on the plane.’

‘But why isn’t she sitting with you?’

‘She’s in the cargo hold.’

The long wooden box was lifted out gently and greeted by booming voices and the stamping of feet across the tarmac. It was morning. Airport workers stood by and watched the fierce haka in silence.

Exhausted, Maia collected her baggage and cleared customs. Sleep, when she could get it, was a brief reprieve, but each time she woke up she had to realise all over again that Aria was gone, forever. It was like standing in a field of shattered glass, shards stuck upright into the earth in all directions, as far as the eye could see.

Her brother was waiting for her in the arrivals hall. They embraced. She stepped back and took a good look at him. She hadn’t seen Tāne in years. His fine features were wreathed in lines.

‘You look old,’ she said.

They walked out to his car without speaking. As the V8 engine sputtered into a loud, low rumble, she lit a cigarette and looked out the window. Patches of scrubby vegetation under a colourless sky.

They arrived to whānau waiting outside the house in light drizzle. A long line of people to hongi and kiss and hug. Maia sat next to Aria on a mattress. At night, someone strummed a guitar and quietly sang. An old friend rushed up and held Maia very, very tight. Countless kids. Maia struggled to identify them, and occasionally would grab one for a cuddle, and ask: ‘Who’s your mother?’

‘Aunty, is that your daughter, eh? Did she fall down?’ a child said, as she gazed at Aria’s body in her coffin.

Big pots of boil-up and fried bread. Cousins in the kitchen. Flowers and messages, even a dozen bottles of good vodka. I can use those, thought Maia. A cloak of kiwi feathers on the coffin, so precious that it must always be accompanied by a caretaker. Photographs of ancestors displayed and spoken to as if they were alive. Karakia in the mornings and at night. Unearthly wailing as the lid was put on the coffin and screwed firmly shut.

The service. Photo slideshow, a life in review. Here she is as a toddler, wearing the plastic gold medals around her neck that she’d loved – Aria, the Champion of the World. Next, a middle-schooler flashing the V sign with her friends at Tokyo Disneyland. Now coltish and doe-eyed, heavy eyeliner accentuating those anime eyes, posing in Hachikō Square. A J-pop song played as the images flashed past.

The burial.

‘Put all your mamae in there with her,’ said a woman whom Maia didn’t know.

Spades dug furiously; blades glinted in the sunshine. Gosh they filled that hole up quick. Her brother’s hand heavy on her back. The sun beat down on them.

Outside the floor-to-ceiling glass, Mount Fuji stood sentinel above stacks of gleaming towers. Maia never thought she’d feel relieved to be back in the office, but the calm pervading the Japanese law firm as attorneys and their secretaries quietly went about their work was a salve. She’d used up all her meagre annual leave in January for the tangi. A full year of work stretching ahead with no holidays was daunting, but she couldn’t think about that now.

Her office was filled with sunlight. She closed the door, took a breath and set to organising her desk. There was a knock. Her boss, a kindly older English man, stood at the door. She nodded. After an awkward moment, he said, ‘Come here,’ and gave her a quick clumsy hug, which made her tear up.

‘What should I say if the lawyers ask how my New Year was?’

‘Don’t tell them. It’ll be easier for you if they don’t know.’

Maia’s ex-husband rang while she was eating a bento at her desk.

‘I saw her,’ said Dai. ‘You know I don’t believe in this stuff. But I know it was her.’

Aria had come to him in a dream. Walking down Meiji Dori near their old house, eight years old, the age she’d been when she first came to Japan.

‘She doesn’t know she’s dead yet, but she’s okay.’

Aria’s best friend, Yuki, dreamed that Aria was building a house for her and her boyfriend in New Zealand.

‘Tell Masaya to stop crying,’ Aria had said.

Tāne had dreamt of her too, which frightened him because Aria asked him to join her.

Maia dreamed of transporting Japanese kokeshi dolls in wooden boxes by bus and being engulfed by wave upon wave of tsunami, but never once of Aria.

Trudging up the hill to catch the train home after work, Maia passed through Roppongi Crossing with all its neon enticements, hostesses and strippers in full hair and make-up hurrying to dates with their customers, touts lying in wait. How was it she was still here? Snatches of Townes Van Zandt songs played on an endless loop in her mind. The master of despair had died on New Year’s Day too, which gave her a strange kind of solace.

It was as if someone had taken a giant roller of paint and covered Maia completely in grey. All she wanted to do was assume the fetal position somewhere dark and quiet, but the pressing need to make a living forced her to maintain the pretence that she wasn’t a shell of a human, a mere placeholder where the person Maia used to be. Her students were lawyers and worked extremely long hours, and like all Japanese, were conditioned to be stoic and to never complain. Yet Maia was one of those people who others felt comfortable telling things to. Many of her students had opened up about their daily worries and concerns, their deepest darkest secrets. Before Aria’s death, she had been happy to listen.

One afternoon, Hama-sensei, a sweet but naive woman in her late twenties, had complained about the other lawyer in her office. Whenever he was finished with a phone call, he would slam the receiver down, startling her.

‘He put the phone down like this, gachan!’ she’d said, and demonstrated the action like a karate chop. This had been going on for months and was driving Hama-sensei mad. Maia’s suggestion to politely ask her colleague to stop doing this was met with wide-eyed scepticism. The other lawyer was her senpai, her senior, and Hama-sensei said that it was impossible to ask him to do anything of the sort without causing deep offence.

‘It’s a big problem, isn’t it?’ Hama-sensei said.

You think that’s a big problem? Maia wanted to say. Try repatriating your child’s body.

Trudging up the hill to the station after work, Maia cried every day.

Maia made three piles: keep, donate, discard. The keep pile was the biggest. She couldn’t bring herself to get rid of Aria’s school uniform, the battered copy of How Maui Found His Mother, the purple Thai Airways blanket that Aria had stolen on their trip to Koh Phi Phi. She couldn’t keep all of Aria’s school books, so she went through and cut out every single place she’d written her name, and put the slivers of paper in a lacquer box. She found a list that Aria had written of the things that she’d wanted to be when she grew up: make-up artist, DJ, stylist. DJ took her by surprise. Dai was a DJ, and on learning that Maia’s current boyfriend was a DJ as well, Aria had declared them to be losers.

A pink plastic hair comb, a single, long, dark brown hair tangled in its teeth. Maia turned it over again and again in her hand. A piece of worthless junk, yet here it was, existing.

Daily routine really started to get to her. Hell, the whole world got to her.

The Hibiya Line, packed on a Thursday morning. Bleary-eyed salarymen clutched their briefcases and nursed hangovers. An office girl, immaculately presented in stockings and tweed suit, constantly nodded off and rested her head on a stranger’s shoulder for a split second before jerking her head upright over and over, never once fully awakening. A group of high-school girls in eye-wateringly short skirts, baggy jumpers and loose socks flipped their hair around and looked at their phones. One, slender with long dark brown hair, slouched nonchalantly in a familiar and startling way. This happened occasionally; in crowds, on subway platforms, outside train stations. Maia’s heart would leap into her throat.

The girl turned her head, and Maia saw that she had bad teeth. Not pretty after all, not beautiful like her, not her.

Why are you alive? she thought bitterly.

Maia couldn’t sleep, again. She lay on her back on the hard sofa bed in the living room. Since Aria’s death, she couldn’t sleep in the room they had once shared in their tiny central Tokyo apartment. Television helped in the evenings, but she’d binge-watched everything, and now there was nothing to do but lie here and wait for the morning. Try not to look into the abyss. A black hole that she could only glance at, give the ole side eye, because she knew that if she were to look directly into it, she’d fall in and disappear. It took a lot of mental effort, this not looking. She was exhausted. Without the energy to toss and turn, her mind finally blank, she stared at the ceiling.

Then, she left her body.

* * *

Maia was floating in mid-air, just slightly above herself. Held gently in the palm of a giant invisible hand. A kind of forcefield. Energy emanated from her palms. There was no thought. Just being. She gazed at a vortex of violet swirling energy directly above her forehead for a long, suspended moment. Was it minutes, or hours? There was no time. She could have stayed there forever.

* * *

The phone rang and rang, its shrill tones breaking the spell, and she was pulled back into her body with a snap. It took a few minutes for Maia to answer it, and her words tumbled out in a useless jumble. She hung up. In that moment, her grief was completely, utterly and entirely gone. She slept peacefully for the first time in almost a year.

Finally, Aria came to Maia in a dream. She was standing in a room filled with moonlight. With a cry, Maia swept Aria up in her arms.

‘I love you, Aria,’ she said. ‘You know that, right?’

Aria didn’t hug her back, but Maia could feel her smile against her shoulder.

‘Mum, I know,’ she said. Sixteen years old, forever. ‘Can I go back upstairs now?’