Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

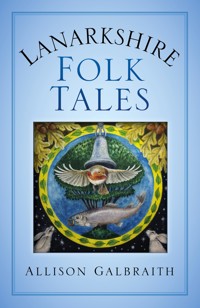

From a cantankerous brownie in Dolphinton to the vampire with iron teeth who terrorised Glasgow, this collection of tales spans fourteen centuries of Lanarkshire's history and happenings. Here you will find the legends of William Wallace's love and loss in Lanark and Saint Mungo's bitter feud with the Pagan hierarchy and Druids, alongside totemic animals, unique Scottish flora and fauna, warlocks, herb-wives and elfin trickery. Allison Galbraith combines storytelling expertise with two decades of folklore research to present this beguiling collection of Lanarkshire stories, suitable for adults and older children.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Catherine (1931-2018) and Donald Galbraith (1929-2018), my mother and father, who fostered my love of writing and telling stories.

To my sister, Marion Galbraith, who introduced me to the intriguing world of folklore when she gifted me a copy of Katharine Briggs’ British Folk Tales and Legends: A Sampler, on my twelfth birthday.

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham

GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Allison Galbraith, 2021

Illustrations © Inky X, 2021

The right of Allison Galbraith to be identified as the

Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9695 2

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Foreword by Donald Smith

Acknowledgements

Introduction

About the Author and Artist

Story Map of Lanarkshire Folk Tales

The Upper Ward

1 Cowdaily Castle

2 Michael Scot and his Industrious Imps

3 The Brownie of Dolphinton Mill

4 Murder on Libberton Moor

5 The Fairies of Merlin’s Crag

6 The Oldest Man in Scotland

7 Fairy Tales from Douglas

8 Nannie’s Invisible Helper

9 The Legend of Cora Linn

10 Stories and Folklore from Lanark’s Castlegate

11 Wallace and the Wraiths of Clydesdale

12 Katie Neevie’s Hoard

13 The Lockharts’ Lucky Penny

14 The Black Clydesdale Horse

The Middle Ward

15 The Blue Flame of Strathaven

16 Sita, the Indian Princess of Larkhall

17 The Cadzow Oaks

18 The Curling Warlock of Mains Castle

19 Tibbie, the Witch of Kirktonholme

20 The Tale of Kate Dalrymple

21 Bartram, the Giant of Shotts

22 The White Hare

23 Maggie Ramsay: The Witch of Auld Airdrie

The Lower Ward

24 The Rutherglen Bannock

25 Saint Kentigern, the Patron Saint of Glasgow

26 How Mungo Came to Glasgow

27 The Battle between Morken and Kentigern

28 The Fish and the Ring

29 The Witches of Pollok

30 The Sheep’s Heid

31 The Govan Cat

32 The Vampire with the Iron Teeth

Story Sources and Notes

Lanarkshire is and always has been a big part of Scotland. It has towns, villages, moorland, river valleys, farms, industrial sites, gardens and orchards. Lanarkshire epitomises lowland Scotland, and continues to play a huge role in the nation’s heritage and culture.

Now, in Allison Galbraith, the region has found a local storyteller able to identify and pull together the wealth of folk tales and folklore that characterises Lanarkshire north and south of the Clyde. Using the ancient ‘Wards’ of the county, she presents three groups of tales to tickle the ear and spice the tongue.

This book is a prime addition to the folk tale volumes produced by The History Press. It combines history and folklore, while giving prominence throughout to the voice of the storytellers. ‘Wait till you hear this …’. Or as people would say in Glasgow, ‘You’d better believe it.’

Allison Galbraith has filled a big gap in our storytelling literature with this fine volume. Local people will be delighted and add to the store from their own memories and experiences. For those who do not know about Lanarkshire this book will be an eye-opener. Enjoy the crack.

Donald Smith

Director, Tracs

Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland

Many thanks to Inky X for his brilliant illustrations and story map.

To Donald Smith for writing the foreword and for suggesting that I put this collection of stories together.

Respect and thanks to editor Nicola Guy for her endless patience, and to her predecessor Matilda Richards at The History Press.

A huge thank you to Alette Willis for her meticulous proof-reading and wise suggestions.

Special gratitude goes to Tessa Wyatt, artist, for her assistance.

Many historians, archivists, librarians and storytellers have supported me in my search for tales. Of these I would especially like to thank:

Paul Archibald at Lanark Library, who was extraordinarily generous with his knowledge and time.

Ed Archer, historian and archaeologist, a walking encyclopedia and force for good in Lanarkshire.

Colin McAllister, my great storytelling friend, who gave me the inspiration for the William Wallace and Marion Braidfute story.

Ewan McVicar, for his invaluable help, encouragement and support.

Alan Steele, for passing on his knowledge of Glasgow tales and showing me the importance of humour in storytelling.

Chris Ladds, for sourcing the Cora Linn story and sharing a passion for historical landscapes, wild flowers and folklore.

Jennifer Macfadyen, whose Doorstep History blog is an inspiration to anyone who wants to delve into Lanarkshire folk culture.

My friend, Robert Howat, for giving me permission to retell his mother Charlotte’s family tale about Queenie the horse.

Tony Bonning, my folklore guru, for finding the Douglas stories and being wonderfully helpful.

Ian Hamilton QC, a genuine legend in his own lifetime, for giving me permission to retell his father’s/family tale about the Hamiltons. And special thanks to Tommy Sherriden – another legend – for connecting me with Ian.

Anne Hunter, for giving me permission to include some of Andy Hunter’s retelling of The Lee Penny.

Raymond Burke, who told me about Ms Kate Dalrymple.

Frank Miller, for my guided tour of Govan and all its treasures – if it’s People that Make Glasgow, (council motto) then Frank is top of the list.

Margaret Bennet, my heroine of Scottish folklore, for her help and suggestions.

To numerous library staff, too many to mention, but particularly to the staff at Biggar Library, Angela Ward from Hamilton Library, Jenny Noble Social History Curator at Summerlee Museum of Scottish Industrial Life, Glasgow Library staff, the friendliest in the world, and Margaret McGinnty at Motherwell Library.

Paul Bristow and all at Magic Torch in Greenock, my favourite folklore friends.

Ian Wallace, for his encouragement and help at the Lanark Archives.

Simon, Mairi and Zak at Waygateshaw House, which deserves its own book of stories.

Lea Taylor, for her unwavering encouragement.

Judy Patterson, for her support and wise words.

My good friend Carol Ward, for giving me a writing retreat.

And lastly, thanks to my generous family and to Finlay Stevenson for helping me to find and explore all the locations in this book.

This collection of folk tales and legends from Lanarkshire spirits us away on a journey around the county. They offer a very human and sometimes otherworldly glimpse of people’s realities past and present. Many of the stories reflect a diverse collection of older folk beliefs and superstitions that also share similarities with ancient folk customs and beliefs found throughout Europe and in other cultures all over the world.

The county divisions and boundaries have changed many times since they were first established in the Middle Ages. Lanarkshire, situated in south central Scotland, once included: the city of Glasgow, most of East Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, South Lanarkshire and North Lanarkshire. Not the largest county in Scotland, but home to one fifth of Scotland’s entire population, so definitely the most populated.

Currently divided into North and South Lanarkshire, with the River Clyde splitting the county neatly down the middle, the whole county resembles a triangular leaf with the Clyde as its stem. Archaeology reveals habitation from as far back as the Mesolithic era (10,000–8000 BCE) and the area was home to numerous ancient Britons and Celtic tribes. Scattered all over the land are cairns, standing stones, circles, a broch (remains in Carnwath) Bronze and Iron Age forts, Viking Hogback burial stones (one in Dalserf, five in Govan) and Roman camps, forts and roads leading to their Antonine Wall in the north. Ten Roman legionnaires are still seen occasionally marching down Watling Street, through Crawford Village in South Lanarkshire, but only from the knees up, the bottom half of their legs lost in the sunken roads of 2,000 years ago.

The tales are divided into three sections, which reflect yet another historical division of Lanarkshire: the Upper Ward, with Lanark as its administrative centre; the Middle Ward, administered by Hamilton; and the Lower Ward, governed by Glasgow. The map and story legend provided show the boundaries of these three wards and where each tale originates from.

The stories here that contain magical or mythological beings – fairies, ghosts, a broonie, a wraith, a mermaid, witches and devils – are told to us as though they are true, making them into folk legends. Although these characters and motifs are shared across a much wider folk culture, certain tales have migrated to particular places and people, and have been absorbed into local history, becoming part of the county’s cultural heritage. They have survived in the rural parishes of Lanarkshire, where calendar customs and the agricultural rhythms of the year are still part of community life. Some of these rituals and celebrations, like summer fairs and gala days, still exist. The town of Lanark celebrates its Lanimer week in June. It’s an exhilarating six days of fun, when the community engage together in old customs and land rites, like the Perambulation of the Marches and the Ride-Out, which date back almost a thousand years.

In Carnwath, they hold the annual Red Hose Race, the oldest surviving footrace in the world, begun in 1508 when James IV of Scotland offered a pair of Red Hose (socks) to the person running most quickly from the east end of Carnwath to the Calla Cross – an incentive to keep soldiers fit.

There is also the New Year bonfire in Biggar, thought to be a direct descendant of a pagan fire rite to ward off evil spirits. The fire has traditionally been huge and so close to the town hall that it beggars belief; however, the old saying, ‘London and Edinburgh are big, but Biggar’s Biggar’ gives us a clue to the grandiose spirit of the town and its customs.

For similar reasons to Biggar’s Hogmanay Bonfire, Lanark’s Whuppity Scoorie ritual, on 1 March (included in the Lanark chapter), literally whips the bad spirits out of town.

While the villages and towns in South Lanarkshire have kept some form of annual community celebration alive, it has been harder for the industrialised northern part of the county to hang on to its folk customs, and also more difficult to find folk tales or legends from North Lanarkshire.

Because most of the region lies on top of coalfields and iron deposits, Lanarkshire became home to the iron industry of the nineteenth century. Something about the process of industrialisation in the north (the middle and lower wards), where the steel industry was located, seems to have broken the folk memory of stories and tradition. Migrant workers who came to work in the county would have brought their own stories and customs with them, and so many of the indigenous Lanarkshire tales faded from memory. There are only three folk tales included in this collection from North Lanarkshire, which probably survived because they were connected to specific features in the landscape. Maggie Ramsay, a witch who haunted the North Burn in Airdrie, was linked to a huge boulder in the burn. The rock is no longer there, but the place was once called ‘Fiddle Naked’ and its association with witches appears to go back much further than the eighteenth century when Maggie’s story was circulating. Another tale, about a family curse, was attached to a glen in Monklands, once known as Lover’s Loup (Leap), which is also gone, the glen having been used as an in-fill site for the by-products of coal mining. The third tale is about Bartram de Shotts, a man of giant stature who terrorised the road to Glasgow and Edinburgh. It is associated with St Catherine’s Well, near Kirk O’ Shotts. The well is still there, a real, physical presence in the landscape, which has helped to preserve the folk memory of Bartram’s legend.

When heavy industries dig, scar and destroy the natural features of the land they appear to take most of the old stories away with them.

Along with the fairy tales, I have included legends of William Wallace and Marion Braidfute, King Robert the Bruce, the Black Douglas, Kings and Queens of the early Brythonic Kingdoms and Lailoken, the most compelling candidate for a real, historical Merlin. Stories migrate and change over many millennia, like the story about Sir Douglas who, while sheltering under a tree in Douglasdale, watched a wyver (spider) spinning her web in a branch above his head, and then took strategic battle inspiration from the spider’s tenacity. Over time and retelling, this story metamorphosed into the tale of Bruce and the Spider. Rumour has it that Sir Walter Scott was the first to swap the protagonists’ names, but maybe that’s just as well, as the story has survived seven hundred years and is still ours for the telling.

Like the folk tales of North Lanarkshire, the folk stories of Glasgow have largely been lost to industrialisation and the huge evolutionary tides of human migration (my own family included). There are hundreds of stories about the city and its inhabitants from the last couple of centuries, but they mostly fall into the ghostly and crime categories. However, I did unearth enough stories from Glasgow that I would enjoy telling at social gatherings and have included them in the Lower Ward section. The oldest are about Saint Kentigern, or St Mungo, as he is better known. Some of his miracles are related on the Glasgow Coat of Arms, which once bore the motto, ‘Let Glasgow flourish by the Preaching of the Word and Praising Thy Name’, now shortened to ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’. This motto relates to one of Mungo’s miracles: while preaching a sermon to a crowd near the Molendinar Burn, the ground rose up beneath him, so that he was elevated high enough for the people to see and hear him. Legends of saints preserved in the early hagiographies have remained popular, celebrated by people regardless of their faith, stories that share the myth and magic of the place to which they belong. Through the stories of Mungo and his miracles, people seem to relate proudly to the city; these old legends giving a rich connection to a distant past in the living present. This demonstrates the power of the oral tale to transcend time and influence us. While presenting a storytelling workshop at a Flood Defence conference in Glasgow, I told a watery Mungo legend – milk gifted by Mungo to an employee is accidentally spilled into the River Clyde, it is not washed away, but churned by the waves and propelled back out of the water, as blocks of miraculous cheese!

Stories are a well-proven, effective way to entertain and educate people, as well as to make saints.

The only tale collected directly from an oral history source, the Black Clydesdale Horse, comes from the cultural life of the county, reminding us of a time in history when this iconic horse breed was as important as the motor industry is today; a time that has now passed, but deserves its place in folk memory. Like the last story in this collection, the Vampire with the Iron Teeth, a real happening reported on all over the world. It proves conclusively that folklore and folk tales are being created in tandem with our existence, the places we live, the activities we enjoy and the stories we choose to share with each other – we are the folk!

There is something peculiar about the nature of folk tales, perhaps created by the act of passing them from teller to listener, into literary sources, then back to the tellers and listeners, over many lifetimes. Sometimes they are forgotten and lost, never to be heard again. Others are rediscovered in old books, songs, newspapers and pamphlets, their magic and wisdom accessible to us once more; like a few of the rare finds in this collection. These stories are multi-generational, suitable for adults and children alike, and even better when shared by young and old together. Perhaps not for younger children though, as some of the tales are too gruesome – Inky X, the illustrator for Lanarkshire Folk Tales, commented that he’d drawn ‘Three decapitated heads in one week!’ An inevitable, bloody consequence of historical legends.

This book is for storytellers, readers and listeners who revel in hearing about the journeys our ancestors took and the stories they brought back with them. I hope you enjoy and pass them on in turn.

Dragon/Dog

sculpture on Cardell Hall,

Govan, Glasgow.

Allison Galbraith has lived in Lanarkshire, Scotland, for over thirty years. While working in the performing arts she began telling stories professionally for Glasgow Libraries in 1992.

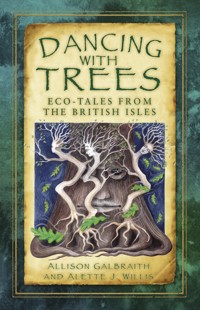

Completing a Masters degree in Scottish Folklore in 2012, she co-wrote her first collection of folk tales with Alette Willis, Dancing with Trees, Eco-Tales from the British Isles, The History Press, 2017.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Inky X is quite simply a genius. You can find him at www.inkyx.com

STORY MAP OF LANARKSHIRE FOLK TALES:

Upper Ward

1. Cowdaily Castle – Carnwath

2. Michael Scot and his Industrious Imps – Carnwath

3. The Brownie of Dolphinton Mill – Dolphinton

4. Murder on Libberton Moor – Libberton

5. The Fairies of Merlin’s Crag – Biggar

6. The Oldest Man in Scotland – Leadhills

7. Fairy Tales from Douglas – Douglas

8. Nannie’s Invisible Helper – Douglas

9. The Legend of Cora Linn – Lanark

10. Stories and Folklore from Lanark’s Castlegate – William Wallace and Marion Braidfute, Whuppity Scoorie, The Girnin Dog – Lanark

11. Wallace and the Wraiths of Clydesdale – Kirkfieldbank

12. Katie Neevie’s Hoard – Lesmahagow

13. The Lockharts’ Lucky Penny – Lanark

14. The Black Clydesdale Horse – Carluke

Middle Ward

15. The Blue Flame of Strathaven – Strathaven

16. Sita, the Indian Princess of Larkhall – Larkhall – Hamilton

17. The Cadzow Oaks – Cadzow – Hamilton

18. The Curling Warlock of Mains Castle – East Kilbride

19. Tibbie, the Witch of Kirktonholme – East Kilbride

20. The Tale of Kate Dalrymple – East Kilbride

21. Bartram, the Giant of Shotts – Kirk O’ Shotts

22. The White Hare – Old Monkland

23. Maggie Ramsay: The Witch of Auld Airdrie – New Monkland/Airdrie

Lower Ward

24. The Rutherglen Bannock – Rutherglen

25. Saint Kentigern, the Patron Saint of Glasgow – Glasgow

26. How Mungo Came to Glasgow – Glasgow

27. The Battle between Morken and Kentigern – Glasgow

28. The Fish and the Ring – Hamilton

29. The Witches of Pollok – Cathcart

30. The Sheep’s Heid – Govan

31. The Govan Cat – Govan

32. The Vampire with the Iron Teeth – Glasgow

THE UPPER WARD

The Douglas family built the original Couthally Castle in the 1100s – a strong single-tower fort on the edge of a moss about a mile north-west of Carnwath. Sir Douglas was fond of feasting and enjoyed a good party. Thanks to these frequent celebrations, the local farmers, castle servants, brewers, cooks and gardeners were kept very busy supplying the food. Almost daily, the butcher slaughtered cattle, diced their parts and loaded the fresh meat on to a cart destined for the castle kitchen. This earned Couthally the affectionate nickname of Cowdaily Castle.

During the turbulent years when Robert the Bruce and his supporters were fighting the Balliol and the English King, the castle was burned down by Lord Somerville, who claimed the ruins of this once grand fort of the Douglas clan as his prize.

Cowdaily Castle had been burned to the ground, leaving only part of the tower standing, so Lord Somerville ordered the men of Carnwath – who were now subject to him – to pull down what was left. When all that remained were a few blocks of granite and a giant mound of rocks, Somerville arrived to view the demolished site. He rode his horse around the moss and hillside accompanied by his advisor, searching for the best place to build a new castle. Finally, Somerville settled for a good location near to the original, but with even better views of Tinto and the other hills to the south.

The next day, Lord Somerville’s foreman gathered a few reluctant men at the market cross. When he had enough workers, he sent them off towards the moss. As they trudged past the thatched houses of Carnwath, an old hen wife looked out from her door, raised a bony finger at them and cackled a warning.

‘Yea’ll get no work finished up there on yon brae, for that ground and those stones are cursed by the Douglas clan. Aye, Douglas had a pact wi the Deil himself and no good will come to any that go agin them.’

After hearing the old wyfie’s warning, a few of the lads were too scared to go on. The foreman growled at them, making it clear that Lord Somerville would do far worse to them than the Devil ever could if they didn’t ‘Get oan wi it, and rebuild his castle.’

The men and boys worked hard shifting stones and rocks from the old castle site to the new location. Foundations were dug and giant slabs of flat stones were laid – fast progress was made on the first day of building. During the night, however, an eerie fog descended on the hillside and unearthly noises could be heard emanating out of it. The men on watch at the building site fled in terror. They ran back towards their homes, stumbling through tough tussocks of moorland grass and falling into deep bogs along the way. They arrived back to their wives and mothers, bedraggled, pale and shaking. Kettles were boiled to make hot reviving tea and drams of whisky served to calm the nerves of the spooked men. The old hen wife heard the commotion in the street and, muttering an incantation to herself, she lit a sprig of dried sage and carefully blew the smoke from the herb about her windows, the door, and up the chimney, so that no evil could enter her home.

The next morning, the villagers were up with the sunrise and out on doorsteps with their neighbours discussing the strange events of the previous evening. It was an angry, red-faced foreman, accompanied by two of Somerville’s armed henchmen, who arrived at the cross that morning to round up builders for the day. Under the threat of being flogged, imprisoned, or both, the local men were given no other option than to go back to work on the castle foundations. When they arrived back at the site where they had laboured so hard the day before, the group were shocked speechless at what they saw – all of their building work had been destroyed. The huge squares of stone had been wrenched from the newly laid foundations and scattered over the hillside. Men slumped to the ground, the blood drained from their faces and their legs weak with fear. Many chanted blessings for protection, while others prayed for forgiveness for betraying their previous lord. Each man remembered the old woman’s prophesy, and now they all believed it was true.

When news reached Lord Somerville about the vandalism of his building endeavours, he was furious. His immediate suspicion was that the men of Carnwath must still be loyal to their old lord and not to him, assuming that they had pulled everything down during the night. When he arrived on the scene and saw for himself how extensive the destruction was, he threatened the men with instant death if they did not begin rebuilding immediately. No one dared to protest their innocence, as they could see that the enraged lord was ready to commit murder if anyone disobeyed him.

All day long and late into the next night, the men worked without a break to rebuild what had been undone. Before midnight, they dragged their tired bodies home to their own beds, ignoring the foreman’s threats of instant sacking if they left the site. The eldest of the workers told the foreman that there was nothing he could do or say to make them stay in that cursed place overnight. Fear of the Devil and what he could do to them was definitely now far greater than the fear of what any man would do to them, even if he was a lord!

The tired group of workers who arrived on the hill the next morning were greeted by a scene of even worse destruction than the day before. This time, Somerville and his henchmen were already storming through the carnage – churned earthworks and boulders strewn around the hillside.

As the men pleaded, declaring their innocence on their mothers’ and children’s lives’, something rang true with Somerville. He’d seen how tired they had been the prior evening, clearly incapable of any further strenuous exercise. Also, he had arranged for two watchmen to sit guard on the road leading to the site. The watchmen swore that no one had approached from the village. However, they reported that they had heard strange and unnatural sounds, and had seen lightning coming from the castle area. Convinced by the wretched villagers’ protests and his spies’ odd report, Somerville decided that he would personally spend the next evening on the hillside, keeping watch for himself.

After the third day of work was completed, the Carnwath workmen were sent home to their village. Somerville and several armed men made camp next to the building site. They sat around a fire, drinking mulled wine, eating roast boar and joking gallusly about the ignorant and superstitious peasants.

At first, they thought nothing of the steel-grey mist that came swirling out of the darkness from the direction of the moss, entwining itself around the partly built castle walls. The fog brought a deep chill to their camp and the men pulled their woollen blankets closer around them and threw more logs on to the fire. Then, from out of the strange, icy fog came an ear-splitting screech, followed by snarls and howls, as though a giant wolf was tearing some inhuman prey into pieces. The startled men leaped to their feet just as the first of the gigantic foundation stones hurtled through the air, travelling past their heads with the velocity of a meteor. More boulders followed, coming in volleys of six, eight, ten rocks at a time and landing between the men and the brow of the hill.

Somerville pulled out his sword and rushed towards the mist and mayhem. However, the eerie ethers wrapped around his legs, his arms and torso, rendering his limbs immobile. He stood paralysed, turning to see that his men were also caught fast. Then, the most terrifying sight appeared before them. As if levitating in a halo of bright, burning dust was the Devil himself. He was cavorting among five enormous demons, ordering each of them to pull down the newly built walls. The sinister demons hurled the granite boulders through the air as easily as if they were playing a game of bowls.

Auld Nic, the Devil, turned his eyes towards Somerville and his men and laughed, sending an explosive jet of bright flame towards them. Each man collapsed, rendered senseless by the sulphuric smog that engulfed them. As they lay helpless on coarse grass and cold earth, they heard the hellish demons chanting:

Tween the Rae-hill and Loriburnshaw,

There ye’ll find Cowdaily wa’, [wall]

And the foundations laid on Ern. [Iron]

When each of the stones from the castle wall had been scattered about the surrounding countryside, the terrifying apparitions and their master, the Devil, disappeared back into the fog. The building work was completely destroyed. All that was left was the smell of scorched grass, sulphur and the frightened men. After many dazed minutes had passed they gathered their wits about them and returned to their lodgings in the village.

Following this experience, and very puzzled by the rhyme that the demons had chanted, Somerville asked for guidance from the local worthies and clergy. None of them could give a satisfactory answer, but one superstitious priest did have the wit to remember the hen wife’s warning. The old woman was summoned. She explained to him that the original castle’s foundations had been built on iron stone, and this had kept the place safe from the Devil’s tricks. If the new lord truly wished to live in Carnwath, then he must build his castle on the same spot as the old one, on the bedrock of iron stone. If he did not do this, she warned, then the Devil would come back with his wicked demons and torment the lord forever.

Somerville took the wise wife’s advice. He built his magnificent new castle on the original castle’s foundation. Not to be outdone by the Douglas clan, Somerville added an extra tower to his fortification – a tower made entirely of stone rich in iron. It was common knowledge, at this time, among the rich and the poor alike, that iron keeps demonic and wicked forces at bay. Although the ordinary folk couldn’t afford to build with ironstone like the rich and powerful Douglas and Somerville families, they made good use of iron nails in their home’s foundations and walls, and every house and barn had a horseshoe nailed to the door for protection against the Devil and his demons.

Note: The castle is now only a ruin, north-west of Carnwath.

Nearly every county in Scotland and Northern England has a story about Michael Scot, the infamous wizard of the north. He was a real person, reputedly born at Balwearie Castle in Fife. Highly educated and a great European scholar of his time (1175–1232), Michael studied philosophy, mathematics and astrology at Durham, Oxford and Paris. He travelled widely, working for the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II as court physician, philosopher and astrologer in Palermo, as well as translating Aristotle from Arabic to Latin.

Although the real Michael was said to have condemned magic in his writing, his connection with esoteric works, Arabic culture and astrology earned him the reputation of being involved with the dark arts, so that within one generation of his death, he was known throughout folk culture as a sorcerer and wizard.

Long ago, in the thirteenth century, the famous Scottish wizard Michael Scot arrived in Lanarkshire and decided to make some improvements to the landscape. Firstly, he wanted to put a large tract of marshy ground, just east of the town of Biggar, to better use. Michael’s ambitious plan was to divert the course of the River Clyde, straight through the unproductive marshland, and into the River Tweed. What a spectacular difference this would make to the people of Clyde and Tweedsdale and to the geographical topography of Scotland. But, more importantly to Michael, this would provide the most splendidly challenging and strenuous employment for his workers.

Now, they were not ordinary men or women that laboured for him, but rather imps and sprites who belonged to the lesser class of demons. Michael had been given the arduous task of keeping this riotous army of imps busy, forever. It was impossible to know how many there were exactly as they were never stationary for long enough to count them all. They were always cavorting, cartwheeling and somersaulting through the air, or jigging, tumbling, disappearing at will, and occasionally bursting into minor explosions of fireworks and flame. There were so many of them that even Michael could not remember their names, or even tell them apart by their wicked, demon-like faces. Three of these creatures had higher status and were clearly the leaders of the pack. Their names were Prig, Prim and Pricker. They were the only ones who spoke directly to Michael.

He had to find continuous work for all of them, or they would get up to terrible deeds, upsetting people and beasts. The wizard had earned this unenviable role, as director of demons, on his twenty-first birthday. His mother, who was reputed to be a mermaid from the River Clyde, had gifted him a sorcerer’s almanac. Once young Michael had absorbed the taboo knowledge of the arcane arts from the great book and began practising the secret lore and dark craft contained therein, the Devil himself had released the multitude of minor daemons to assist Michael Scott until his dying day!

For the first stage of Michael’s landscaping venture, he instructed the imps to build a stone bridge over the River Clyde at Covington. The local people of the neighbouring parishes of Carnwath and Libberton were excited at the prospect of the bridge, which would make their journeys to the market at Biggar so much safer and faster. All these folk knew about the huge road improvements Michael and his unholy army had made throughout Scotland; sturdy bridges and roads, where nothing but marsh and bogs had once existed. They knew that it was thanks to the wizard’s power over the hellish minions that Great Watling Street had been built along the spine of the country, connecting the far counties of England all the way up to Lanarkshire and beyond.