23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

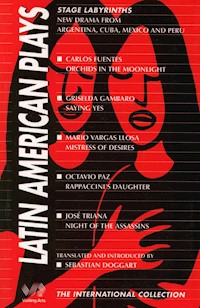

An essential introduction to the fascinating but largely unexplored theatre of Latin America, featuring new translations of five contemporary plays written by some the region's most exciting writers. Each play is accompanied by an illuminating interview with its author conducted by the theatre director, Sebastian Doggart, who has also selected and translated the plays and provided an introductory history of Latin American drama. Rappaccini's Daughter by Octavio Paz A play by the Mexican Nobel laureate. Night of the Assassins by José Triana A controversial Cuban play in which three siblings plot the murder of their parents. Saying Yes by Griselda Gambaro A grotesque comedy from Argentina about man's inhumanity to man. Orchids in the Moonlight by Carlos Fuentes A dream play about two Mexican women exiled in Hollywood's maze of mirrors. Mistress of Desires by Mario Vargas Llosa Peru's most acclaimed writer interweaves reality and fantasy in an erotically charged tale.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

LATIN AMERICAN PLAYS

New Drama from Argentina, Cuba, Mexico and Peru

Rappaccini’s Daughter Octavio Paz

Night of the Assassins José Triana

Saying Yes Griselda Gambaro

Orchids in the Moonlight Carlos Fuentes

Mistress of Desires Mario Vargas Llosa

Selected, translated and introduced by

Sebastian Doggart

THE INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

An Introduction to Latin American Theatreby Sebastian Doggart

Select Bibliography

RAPPACCINI’S DAUGHTERby Octavio Paz

Interview with Octavio Paz

NIGHT OF THE ASSASSINSby José Triana

Interview with by José Triana

SAYING YESby Griselda Gambaro

Interview with Griselda Gambaro

ORCHIDS IN THE MOONLIGHTby Carlos Fuentes

Interview with Carlos Fuentes

MISTRESS OF DESIRESby Mario Vargas Llosa

Interview with Mario Vargas Llosa

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

An Introduction to Latin American Theatre

by Sebastian Doggart

Latin American theatre is an untapped goldmine for the English-speaking world. While the region’s novels and poetry are widely read and respected, its theatre remains largely unknown. Few Latin American plays are published or produced in English, and these often suffer from unsympathetic translations. School and university courses mostly ignore Latin American theatre and there is a dearth of critical studies on the subject. The main purpose of this book, therefore, is to encourage the reading, study and staging of Latin American drama.

The book has three sections. First, it presents original translations of five contemporary Latin American plays, which have been prepared in collaboration with the playwrights themselves, and chosen for their high literary and dramatic quality. Although they have specifically ‘Latin American’ features, they retain qualities that give them a universal accessibility. To test this, all five plays were staged in the UK by English-speaking performers, and these productions have yielded fresh insights into the authors’ intentions, which have been incorporated into the translations. The plays’ broad range of styles and subject matter is representative of the rich diversity of drama written since the 1950s. The chosen writers represent four of the most historically vibrant centres of Latin American theatre – Cuba, Mexico, Argentina and Peru – and their work is concerned with many of the issues and patterns that have preoccupied Latin American dramatists for over five centuries. The second section of the book contains interviews with the playwrights, giving the writers a chance to explain to an English-speaking audience the intentions behind their plays, and to reveal some of their literary and personal sources. The third section is this introduction which contextualises the plays through a historical survey of drama in Cuba, Mexico, Argentina and Peru, and then discusses some of the challenges involved in translating and staging Latin American drama in English.

A Brief History of Latin American Theatre: Pre-1492

Our knowledge of the pre-Columbian period is very limited. Europeans who discovered indigenous spectacles judged them to be primitively heretical, banned public performances, and destroyed local records. What information we do have comes from Catholic missionaries, whose reports agreed that throughout the region there was theatre in the form of ‘ritual spectacles’, such as Cuban areitos, in which Arawak Indian actors dressed up to enact historical and religious stories using dialogue, music and dance, until they were prohibited by the Spanish colonial administration in 1511. The Aztecs in Mexico used a mixture of dance, music and Nahuatl dialogue to depict the activities of their gods. According to Fray Diego Durán, a Dominican friar, one Aztec festival required a conscripted performer to take on the role of the god Quetzalcoátl. As such, he was worshipped for 40 days, after which, to help Huitzilopochtli, god of daylight, fight the forces of darkness, his heart was removed and offered to the moon. His flayed skin was then worn as the god’s costume by another performer. While the Incas ruled Peru, the Quechua are reported to have performed ritual spectacles involving dance, costumes and music, but probably not dialogue, to purify the earth, bring fertility to women and the soil, and worship ancestral spirits. The Inca Tupac Yupanqui used his warriors to re-enact his son’s victorious defence of the Sacsahuamán fortress above Cuzco against 50,000 invaders.

The only pre-Columbian ‘script’ to survive the European campaign against indigenous culture, the Rabinal Achí of the Maya-Quiché Indians of Central America, is the story of a Quiché Warrior who is captured after a long war by his sworn enemy the Rabinal Warrior and, when he refuses to bow down to the Rabinal Warrior’s king, is sacrificed. The story was told through sung formal challenges, interspersed with music and dance, with each actor wearing an ornate wooden mask which was so heavy that the actors had to be replaced several times during the performance. The last actor playing the Quiché warrior was sacrificed. The work was preserved through oral tradition, until 1855 when it was recorded in writing by Charles Brasseur, a French priest in the Guatemalan village of Rabinal. It is still performed there every January – omitting the final sacrifice.

1492-1550

The arrival of the Spaniards led to a blending, or mestizaje, of local and European influences, which has since become one of the most distinctive features of Latin American theatre. Catholic missionaries identified the theatre as an effective tool for converting the local people to Christianity, and in Mexico, the Franciscans sought to transform the religious beliefs of the Aztecs by learning Nahuatl and studying their rituals and ceremonies. In doing so, they found that Aztec and Christian religions had much in common: the Aztecs associated the cross with Quetzalcoatl, ‘baptised’ newly-born children, ‘confessed’ to the gods when they transgressed, and practised ‘communion’ through the eating of human sacrifices. The Franciscans dramatised such symbols and rituals in the local language, so that the Aztecs would become more open to conversion through identification with the characters.

Theatrical presentations were usually staged in ‘open chapels’, built on the site of indigenous places of worship, with wooden platforms resembling end-on stages. Mass preceded performances, which were based on local dance and song, and celebrated European religious and secular authority. In the early 1500s, the Church turned to a more effective technique for storytelling and evangelising: a modified version of the Spanish auto sacramental, a one-act religious allegory which was performed on feast days, especially Corpus Christi. Such Indo-Hispanic autos are the first theatrical works to be described legitimately as ‘plays’, in that they were formally scripted. The Catholic missions also put on large-scale productions for mass conversions and to foster new communities revolving around the Church. One of the most spectacular of these events was the Franciscan production of the auto, The Conquest of Rhodes (La Conquista de Rodas, 1543) in the Mexican town of Tenochtitlán, where construction of the set alone required the work of some 50,000 Indians.

1550-1750

From the mid-16th century Indo-Hispanic evangelical theatre began to wane as secular authorities wrested influence away from the Catholic missionaries. Radical demographic changes contributed to this: by 1600, the Indian population in Latin America was estimated to be only one tenth of what it had been 100 years earlier. Many immigrants were arriving from Europe, and there was a growing mestizo (part Indian, part European) population whose idea of entertainment was far removed from evangelising theatre in indigenous languages. European influences became dominant. Spanish baroque dramatists like Lopé de Vega, Calderón de la Barca and Tirso de Molina refined the auto sacramental, and developed two other dramatic forms which they combined with the auto: the loa, a short dramatic prologue in praise of visiting dignitaries or to celebrate royal anniversaries; and the sainete, a musical sketch, inserted between acts, which made fun of local customs or of the auto itself.

Such innovations encouraged the emergence of Latin American dramatists like Mexican-born Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Peruvian Juan del Valle y Caviedas and the Argentine Antonio Fuentes del Arco whose best-known play, Loa (1717), celebrated the repeal of a tax imposed in Argentina on the importation of the herb mate from Paraguay. Particularly notable is the work of the Mexican nun, poet, intellectual, scientist, and early ‘feminist’ Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. She wrote seventeen loas, three autos, two sainetes, and two secular comedies. Formally her theatre fits within the conventions of the Spanish baroque, and her comedies were particularly influenced by Calderón; yet the content of her work shows an independent mind verging on the subversive. For a Mexican woman in a colonial, male-dominated society, it was a remarkable achievement just to have had her plays performed. Her treatment of subject matter and characterisation boldly questioned colonial, religious, and male power. In her secular comedy of errors, The Desires of a Noble House (Los empeños de una casa, c. 1683), for example, she dressed up a male character in women’s clothes to ridicule the way men expected women to assume subservient roles. She also became one of the first Latin American dramatists to confront the scorn shown by the Spaniards for indigenous cultures, particularly in the loa to her auto, The Divine Narcissus (El Divino Narciso, c.1680), where two characters discuss whether such ‘primitive’ culture as Aztec dance and music would be suitable for performance at the Spanish court.

Sor Juana’s drama is the first example of Latin American ‘autonomous theatre’, which is defined as theatre attempting to establish personal or cultural identity by using dramatic forms to question, ridicule or resist an oppressive status quo, or to celebrate the beliefs and customs of an oppressed culture or social group. The emergence of autonomous theatre coincided with a growing desire for independence from Spain, which was clearly demonstrated in the Mexican and Cuban insurrections of 1692 and 1717; and the concept of the ‘autonomous’ was to play a major role in subsequent Latin American theatre, including the five plays in this volume.

1750-1900

The reign of the autos in Latin American theatre came to an abrupt end in 1765 when the Spanish king Charles III banned them for being religiously corrupt. They were largely replaced by European-inspired neoclassical and romantic plays. In general, the use of European forms stunted the development of home-grown Latin American theatre, perpetuating the region’s cultural dependence on the Old World. The Spaniards contributed more positively, however, by implementing a region-wide programme of theatre construction. Their buildings were generally of a classical style, using proscenium arch stages, and were intended to glorify their colonial sponsors. In the early 19th century, the Cuban Governor Tacón set out to build the biggest theatre in Latin America by levying a hefty tax on slaves imported into the island. The eponymous theatre seated 4000 and had 150 boxes.

This was also the period when much of Latin America gained its independence from Spain: Mexico in 1810, Argentina in 1816, Peru in 1822 and Cuba in 1898. Theatre contributed to and fed off these social and political upheavals, with many plays depicting the Spaniards negatively, especially historical figures like Cortés and Pizarro, while indigenous and local life was celebrated through costumbrismo. Cuban playwrights were probably the most outspoken critics of the Spaniards during the last decades of colonial rule. José María Heredia used classical stories to draw parallels with the corrupt tyranny of Spanish rule. His The Frightened Peasant (El Campesino espantado, 1820) is a one-act sainete about a man from the country abused by the urban colonial authorities, while The Last Romans (Los Ultimos Romanos, 1829) symbolises the decaying Spanish empire. Heredia’s work angered the Cuban authorities so much that he was forced into exile – as was his compatriot José Triana 150 years later.

Bufo, another example of Cuban autonomous theatre, developed out of the tradition of the sainete and was influenced by the North American minstrel groups that toured the island between 1860 and 1865. Bufo shows had three main characters: the gallego (a white Galician immigrant), the negrito (a white actor with a black face) and the mulata (an Afro-Cuban woman fought over by the two men). They used a distinctive mixture of Spanish, French, English and Yoruba and were often critical of the colonial authorities. At one show in 1869, a bufonero called Jacinto Valdés was bold enough to shout “Viva Céspedes”, the name of a revolutionary leader. Spanish officials reprimanded him, but Valdés defied them by arranging the next show as a special benefit to raise money for Céspedes’ forces. This time, when Valdés incited the audience to chant “Cuba Libre!”, colonial soldiers broke into the theatre and opened fire on the audience, killing many, and forcing Valdés to flee the country. The following day, the newspaper La Patria Libre published Abdala, a one-act dramatic poem by the 16-year-old poet and subsequent political activist José Martí. Abdala tells of a Nubian soldier who, against his mother’s wishes, leaves home to help save his people from invading Arabs, and dies in battle – a tragic prophesy of Martí’s own violent death fighting the Spaniards in 1895. Like Heredia, Martí’s theatre used historical analogy to encourage resistance to colonial rule.

A key development in the Argentine theatre, meanwhile, was the emergence of the gaucho, the cowboy of the pampas, as a symbol of cultural autonomy. The gaucho fiercely resisted any constraints on his personal freedom, particularly those imposed by the colonial authorities, and then, after Independence, by the urban government. From these seeds grew the teatro gauchesco, epitomised by the theatrical adaptation of Juan Moreira, a popular serialised novel by Eduardo Gutiérrez. The plot is relatively simple: Juan wants a comfortable family life but a provincial official desires his wife. A shopkeeper reneges on a debt to Juan, and is supported by the covetous official. Angry and dishonoured, Juan kills them both and becomes an outlaw. Although he helps the poor and cleverly avoids capture, he is eventually surrounded and killed. Two different productions were staged. The first version, in 1884, had no dialogue and featured a famous Uruguayan clown, José J. Podestá, in the leading role. It was performed in the round as a pantomime, with horses, musicians and dancers. Two years later, Podestá produced another version, also in the circus ring, adding dialogue in the authentic gaucho dialect. It was hugely popular, ran for five years and inspired a host of other gaucho plays, notably Martiniano Leguizamón’s Calandria (1896).

Just as the teatro gaucho stood for a particular way of life, other Latin American playwrights used costumbrista theatre to celebrate local colour and customs. Mexican audiences applauded the social comedy of its sainetes, while in Peru the playwright Manuel Ascencio Segura caricatured the army in Sergeant Canute (El Sargentin Canuto, 1839) and delighted audiences with his portrait of a Lima matchmaker, Na Catita (1856).

1900-1920

Argentina and Uruguay became the hub of Latin American theatre in the early 20th century. Industrialisation was under way and European immigrants flooded into Buenos Aires which saw a population explosion from 187,000 in 1869 to 1.6 million in 1914. Uruguayan-born Florencio Sánchez powerfully portrayed the way urbanisation was changing everyday life. Sánchez shared with his teatro gauchesco predecessors a preoccupation with the conflicts between the individual and society and between urban and rural lives; but he condemned the idealisation of the gaucho. His two most performed plays are La gringa (1904), about a young European immigrant girl’s struggle to survive in the New World, and Down the Gully (Barranca abajo, 1905), a three-act rural tragedy about an old gaucho whose ranch is threatened by legal action from an immigrant city-dweller. His wife and daughters pester him to allow them to socialise more. When he resists, one daughter starts a relationship with the immigrant. The other, Cordelia-like, remains loyal to him, but when she dies of tuberculosis, the gaucho decides to commit suicide.

The conflict between immigrants and locals, or creoles, also lay at the heart of new urban sainetes, which explored the social, cultural and linguistic contradictions of life in Buenos Aires. Throughout Latin America the sainete had become established as a genre in its own right, and the urban form had one act and two central characters, the immigrant and the creole, who usually spoke different dialects. The styles ranged from political satire to social caricature and melodrama, and the most successful writers of urban sainetes were Alberto Vacarezza and Nemesio Trejo.

In Cuba, dramatists were confronting significant political changes. Cuba obtained nominal independence from Spain in 1898, but in 1901 the USA inserted the so-called ‘Platt amendment’ into the Cuban Constitution, authorising US intervention ‘as necessary’. The USA also forced economic dependence on Cuba by monopolising sugar exports for the US market and by securing free access for US capital and goods. One of the plays which gave vent to the growing resentment to US neo-colonialism was Rebel Soul (Alma Rebelde, 1906) by José Antonio Ramos.

In Mexico, the cosy cultural conservatism of the Porfirio Diaz regime exploded with the revolution of 1910. The only notable theatrical activity in the ensuing civil war was the emergence of political revue, in which performers used local language to satirise the new leaders. The 1917 Mexican Constitution put education high on the social and political agenda, and with it came the promise of theatrical renewal.

1920-1940

Conflicting desires to create autonomous Latin American theatre and to yield to the powerful influences of European and US theatre dominated this period. On the one hand, theatres like Teatro Orientación in Mexico and Luis A. Baralt’s Teatro de la Cueva in Cuba staged works by writers like Pirandello, Chekhov, Shaw, O’Neill, Cocteau and Strindberg, European ideas about the role of the director gained widespread acceptance, as did Stanislavski’s acting ‘system’, and theatres throughout the region were relying on imports for technical innovations in staging, lighting and sound. On the other hand, artists and intellectuals throughout the region were searching for national identities and making determined efforts to free themselves from cultural dependence on Europe and the USA. Nationalist sentiment was strongest in Mexico. Like the Catholic missionaries, the new revolutionary rulers saw theatre as an effective tool of mass education. One of the first big state projects was the construction of a 9000-seater open-air theatre which staged Erfrén Orozco Rosales’ aptly titled Liberation (Liberación, 1929), which set out to teach the glorious story of Mexico City from its conquest by the wicked Spaniards to its triumphant salvation through the revolution. The production had a cast of over 1000 performers, echoing the mass evangelical productions of the 16th century. Pleased with the success of the project, the government instigated an incredible two-year construction programme during which some 4000 new theatres were built in both urban and rural areas. Orozco Rosales continued to write strongly nationalist drama which either celebrated the revolution, as in Land and Liberty (Tierra y Libertad, 1933), or extolled the power of the Aztec spirit, such as Creation of the Fifth Sun (Creación del Quinto Sol, 1934), which used a cast of 3000 to tell the story of two Aztec gods who saved the world by throwing themselves into fire in order to create a new sun and moon.

The desire to create autonomous theatre in Argentina led to a new form, the ‘creole-grotesque’. As in the teatro gauchesco, the urban sainetes and the work of Florencio Sánchez, the main conflict in the creole-grotesque is between the individual and society. The form arose out of the work of two Argentine playwrights – Francisco Defilippis Novoa and Armando Discépolo. Both were influenced by a mixture of anarchist thought and the promise of Christian mercy. Their definition of the ‘grotesque’ can be described as the discrepancy between a character’s inner self and his outer mask. The dramatists heightened this tension by calling for exaggerated sets, lighting, costumes, and makeup, and by the use of deforming mirrors and masks. Nevertheless, both writers encouraged ways of overcoming ‘grotesque’ human traits: Discépolo called on society to reject hypocrisy and to show greater compassion for the struggling individual, particularly the immigrant; while, in contrast, Defilippis Novoa suggested that redemption was in the hands of the individual and could only be achieved by accepting God. His Christian fable, I Have Seen God (He Visto a Dios, 1930), which illustrates this hope, is the story of a cruel and dishonest pawnbroker, Carmelo, who loses the one thing he loves, his son Chico. Carmelo gets drunk and is tricked by his assistant, Victorio, disguised as a vision of God, into handing over his money. When Chico’s pregnant girlfriend also attempts to rob him, Carmelo’s Bible-selling tenant intervenes to save him: sober again, Carmelo forgives all, gives away his business and leaves to find God in himself.

Discépolo and Defilippis Novoa have had a significant influence on Griselda Gambaro’s work. This period of Argentine theatre also produced a precursor for, if not a direct influence on, Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa, in the form of the playwright and novelist Roberto Arlt. Arlt was inspired by literary works like Don Quijote and by the paintings of Goya, Brueghel and Dürer. In plays such as Saverio the Cruel (Saverio el cruel, 1935) and The Desert Island (La Isla Desierta, 1937) conventional reality is combined with the world of dreams – dimensions which are similarly interwoven in Mistress of Desires and Orchids in the Moonlight.

1940-1959

During this period there was a temporary lull in the debate among Latin American theatre practitioners about whether or not a truly national drama should reject European cultural influences. The Cuban writer Fernando Ortiz suggested that ideas borrowed from another culture set off a complex process of ‘transculturation’, leading to the creation of entirely new cultural phenomena: such a view made the question of influences largely redundant. At the same time there was a growing awareness of the need for better financed theatre companies and for training. Governments throughout the region responded by setting up drama colleges and national theatres and by funding independent groups. The Cuban Academia de Artes Dramáticas was founded in 1941 to provide actor training, and in 1949 Havana University set up the Teatro Experimental to encourage the development of national playwrights through an awareness of international theatre traditions. In Mexico, many new theatre companies were formed in the 1940s. The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes was created in 1947 to train actors, maintain repertory theatres and organise annual drama festivals. Meanwhile, two important new institutions were established in Peru: a national theatre company, the Compañía Nacional de Comedias, and a national drama college, the Escuela Nacional de Arte Escénica.

In this supportive environment play-writing thrived. In Mexico, actor, translator, producer, teacher and playwright Rodolfo Usigli emerged as the bright new star of the national theatre. Although his plays are deeply Mexican in their passionately critical exploration of the national psyche, Usigli admired European dramatists and ‘acculturated’ some of their formal techniques, especially those of his friend George Bernard Shaw. Usigli’s best-known play is The Impostor (El Gesticulador, 1947), a complex satire of social hypocrisy and deception revolving around a history professor who distorts Mexican history for his own political ends. The play caused a scandal when it was published, provoking a cabinet crisis, and it remained unproduced for ten years. Since then, it has been performed regularly and successfully throughout the Americas and Europe. Usigli’s influence on Mexican theatre is difficult to over-estimate. His plays showed audiences how Latin America represented the ‘Other’ to Europe’s ‘Self’. Playwright Luisa Josefina Hernández whose profound characterisations and unusual story-telling talent is best shown in the collection of dialogues called Big Deal Street (La Calle de la Gran Ocasión, 1962), acknowledges him as her mentor.

In Argentina, the search for a national drama remained intense, as shown in the plays of Osvaldo Dragún, a leading writer of ‘autonomous theatre’ of this period. Like Usigli, he sought to expose the hypocrisy of politicians and the middle classes. He was deeply concerned with the social injustices that Peronism had failed to address. The political content of Dragún’s work is well illustrated in The Plague Comes from Melos (La Peste Viene de Melos, 1956), which, though set in Ancient Greece, is an implicit critique of the USA for the way its ostensibly anti-Communist foreign policies masked darker imperialist ambitions. It had particular resonance in the wake of the CIA-backed coup which overthrew Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz in 1954. Dragún also experimented with formal techniques: in Stories to Be Told (Historias para ser contados, 1957) he used songs, dialogue and mime in a succession of one-act plays to explore the dehumanising effects of materialism. During successful productions in the USA and Europe, critics compared him to Brecht and his theatre conventions to the commedia del arte; but Dragún’s work is essentially Argentine, rooted in the urban sainete and the creole-grotesque.

Another playwright who used classical settings to explore local reality was Virgilio Piñera. He vividly exposed the fear behind Cuba’s cheerful facade. His first work, Electra Garrigó (1948), was an absurdist parody of Sophocles’ Electra, reinterpreted in a vein of black humour. A flavour of Piñera’s wit can be gained from a summary of the plot of Jesús (1950) in which a barber named Jesus Barcia, son of Joseph and Mary, is rumoured to be the Messiah, despite his protestations to the contrary, and is eventually stabbed to death for refusing to work miracles. (Both the grotesque humour and the hairdresser’s setting are echoed in this volume in Gambaro’s Saying Yes.)

Peru emerged from 50 years of theatrical stagnation in these years with some fine new playwrights. Sebastián Salazar Bondy wrote with nationalist intent and met with international acclaim. He experimented with forms ranging from satirical farce, as in Love, the Great Labyrinth (Amor, gran laberinto, 1947), to historical drama, with Flora Tristrán (1958). Salazar Bondy was also a noted poet, and shared with many Latin American dramatists since Sor Juana the ability to combine theatrical work with poetry and prose fiction. Such creative breadth is of special relevance to our understanding of the theatre of Octavio Paz, Fuentes and Vargas Llosa, who are not generally identified primarily as playwrights.

Poet, essayist, teacher, editor, diplomat, and Nobel laureate, Paz is a central figure in contemporary Latin American literature. He was born in 1914 in Mexico City, where he grew up. He fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War and moved to the USA in 1943. In 1945 he joined the Mexican diplomatic service, which led to extensive travel. In 1950, Paz shot to international literary fame with his essay on Mexican character and culture, The Labyrinth of Solitude. Five years later, he published a seminal essay on poetics, The Bow and the Lyre, and in 1956 turned his attention to an exploration of the role of poetry in the theatre. He gathered together Mexican writers and artists, including the painter Leonora Carrington, and set up the experimental theatre group Poetry Out Loud (Poesía en Alta Voz). The group rejected realism, instead defining theatre as a kind of game, and produced eight programmes of plays, ranging from Greek and Spanish classics to modern Mexican works, the most notable of which was Rappaccini’s Daughter, the only play written by Paz. Poetry Out Loud also gave Elena Garro her big career break, by producing her play The Lady on Her Balcony (La Señora en Su Balcón, 1963), a poetic and disturbing portrayal of an elderly woman haunted by the illusions of her past. Garro’s imaginative use of physical images to depict external realities made her a leading Mexican dramatist of the 1960s and 1970s.

The symbiosis of prose fiction and theatre is best illustrated by the work of Guatemalan-born Miguel Angel Asturias. Winner of the 1967 Nobel Prize for Literature, he is best known for his novels Mr. President and Men of Maize, and for his anthropological study of Guatemalan legends; but he also wrote four plays in which he combined fantasy and psychology, the modern and the mythical. Soluna (1955), for example, is a dream play which starts as a naturalistic drama, and is then transformed by masks, music and dance into a ritual spectacle of pre-Columbian magic.

1959-1980

These were the most fertile years thus far in Latin American theatre, marked by unprecedented achievements in both quality and volume. The number of locally written plays produced increased sharply during this period: for example, while only 40 Cuban plays were put on in Havana between 1952 and 1958, 281 were staged in 1967 alone. All over the region new playwrights were seeing their work produced and were attracting international critical and public acclaim. These plays grew out of a period of confrontation and transition. The 1959 Cuban revolution encouraged people throughout the region to believe that political transformation could overcome social inequalities, corruption, and US imperialism. The Catholic Church gave its support to social change, and Gustavo Gutierrez and his ‘theology of liberation’ inspired Paulo Freire and others to set up ‘base communities’ to transform society from the grass roots. But aspirations for a region-wide revolution died with Ché Guevara, and public expressions of political opposition were met with violence. Authoritarian governments took control in Argentina and Peru, the Cuban revolution ossified, the USA implemented neurotic anti-Communist policies, and the Vatican retreated into the ultra-conservatism of John Paul II’s papacy. Against this turbulent backdrop, the theatre often provided the only place where people could freely express their hopes for change.

José Triana ranks among the most significant writers of Latin American autonomous theatre. Triana was born in Bayamo in 1932, studied in Cuba, and was inspired by José Martí as a student. He became a friend of Virgilio Piñera, who encouraged him to publish his poems in Cuban literary magazines. Triana took an active stance against the Batista government and, following a number of failed rebellions, was forced into exile in Spain, where he became involved in the theatre, saw many plays, and started writing his own. He returned to Cuba after the revolution and, inspired by Piñera’s Electra Garrigó, completed Medea in the Mirror (Medea en el espejo, 1960), which placed classical tragedy figures in a humble Cuban setting. His fifth play, Night ofthe Assassins is, in social and political terms, undoubtedly the most significant work of the period. Writing started in 1957 and the play had its Havana premiere in 1965. It won the prestigious Casa de las Américas award, and was subsequently performed throughout the Americas and Europe. It is an unsettling and complex work, which elicited many interpretations: some took its 1950s setting as an attack on pre-revolutionary society under Batista, others picked up on Lalo’s last lines to argue that the play was a clarion call for the redemptive power of Love, while the Cuban Ministry of Culture interpreted the play as a direct attack on the incompetence and complacency of Fidel Castro’s government. This was indeed one of Triana’s intentions and he was to suffer dearly for it. The Ministry judged him to be “outside the revolution”, denied him the resources to stage plays like War Ceremonial (Ceremonial de Guerra, 1968-73) and Frolic on the Battle Field (Revolico en el campo de marte, 1971), and marginalised him from active cultural life. In 1980, Triana emigrated with his wife to Paris.

Another seminal writer of autonomous theatre to emerge during this period was Griselda Gambaro. Born in Buenos Aires in 1928, she worked in accounting and business until she got married and, in her words, her husband ‘emancipated’ her. She wrote her first play aged 24, since when there have been over 30 further plays, as well as several novels. Gambaro’s work paints a deformed and unnerving portrait of a tragic period in Argentine history. Starting with the military coup that ousted Perón in 1955, these years were marked by an uneasy succession of military and constitutional regimes. Perón’s return to power in 1973 was short-lived, and his death in 1974 unleashed a rash of political violence from left-wing guerrilla groups and right-wing death squads. In 1976 the ruling military junta vowed to rid the country of ‘subversion’ and instigated the ‘Dirty War’, during which the army crushed both the guerrilla movements and its civilian opponents. Gambaro herself was forced to flee to Spain after her novel Earning Death (Ganarse la Muerte, 1976) was banned as ‘subversive, amoral and harmful to the family’, and after she had received death threats. Her nightmarish portrayals of abductions in The Walls (Las Paredes, 1963) and fascist excesses in The Camp (El Campo, 1967) grimly predicted the summary executions and torture which were to ‘disappear’ an estimated 15,000 Argentines. In The Blunder (El Desatino, 1965) she exposes the passive compliance with which many accepted military repression. In later plays like Antígona Furiosa (1986) female characters take on more central roles and often take bold steps to resist patriarchal oppression. Gambaro’s work mines a human propensity to victimise others, and is directly descended from the creole-grotesque dramatists of the 1920s. Gambaro’s language is an extraordinary hybrid of Argentine slang, the encoded dialects of tyrannised people, and diverse cultural references: in her promenade play Information for Foreigners (Información para Extranjeros, 1973), for example, she seamlessly interweaves porteño jokes with a lullaby from Lorca’s Blood Wedding, an account of Stanley Milgram’s experiments on the human capacity for violence, and extracts from Othello.

A very different form of autonomous theatre to have a big impact between 1960 and 1980 was ‘New Theatre’. Pioneered by Enrique Buenaventura’s Teatro Experimental de Cali in Colombia, and rooted in the base groups of liberation theology and a version of Brechtian epic theatre, New Theatre’s ideological objective was to create a radical alternative to ‘bourgeois’ drama. New Theatre was to be based on five principles. First, it would be the product of collective work rather than the imagination of an individual author; although there would be one overseeing director, an egalitarian structure would be established so that every participant would be simultaneously actor, writer, researcher and technician. Second, New Theatre would perform theatre for, and to, communities unfamiliar with the theatre. Third, whereas the messages of bourgeois theatre were passively received by the public, the audiences of New Theatre would be invited to participate actively in the performances; in this way, a play would be rewritten at each performance. Fourth, New Theatre would seek to transform reality not just to interpret it, not to preach ideas but to set up dialectical situations and then engage audiences in debating them. Fifth and finally, whereas bourgeois drama valued the cultured, the eternal and the universal, New Theatre sought the immediate and the popular: plays would use local colour, language and music, and would be a theatre of theatricality rather than of staged literary texts.

These principles were rigorously applied by Cuba’s Teatro Escambray, set up by director Sergio Corrieri in 1968 as ‘an effective weapon at the service of the Revolution’. The production of The Judgment (El Juicio, 1973) was inspired by a real-life counter-revolutionary insurrection in a small mountain community where the group had settled. Interview data was collected from the area, with questions concentrated on how society should treat an individual opposed to the revolution. Corrieri then developed a script with the actors through improvisations. The actual performance was in the form of a trial, with the audience seated in a semi-circle. Before the start of the show, six members of the audience were chosen as a ‘jury’ and came on stage to listen to witnesses and to ‘judge’ a man accused of counter-revolutionary activities. After the hearing, the ‘jury’ met backstage to decide his fate and deliver its ‘verdict’.

There have been numerous variations of New Theatre, the most notable by the Brazilian Augusto Boal and the Nicaraguan Alan Bolt. But New Theatre and ‘collective creation’ techniques have been attacked on many grounds. A common criticism (and one which Mario Vargas Llosa voices in his interview in this volume) is that neglect of the text produces an ephemerality in the work that impoverishes the theatre. A second criticism has been that egalitarianism within groups rarely existed, since the ‘power’ that was wrested from the writer was merely transferred to the director. Alienation from the community/ audience was a further problem, in that most of the dramatised situations were chosen and set up by groups with their own agendas in mind. Such criticisms significantly weakened the New Theatre movement during the 1980s.

The ‘boom’ in Latin American novels during this period gave new impetus to the cross-fertilisation between theatre and other literary genres. Gabriel García Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, published in 1967, was the first of a series of worldwide successes for novelists like Isabel Allende, Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes. It sent shock-waves throughout Latin American culture, which had shown itself capable of competing independently on a world stage. ‘Magic realism’ managed to touch nerves that were both universal and specifically Latin American, and became an inspiration for painters and film-makers. Theatrical adaptations of novels and short stories were produced throughout the region, as playwrights and directors sought to appropriate the language, images and structures of prose fiction.

Poetry continued to influence the theatre, often through the collective-creation methods applied by the New Theatre groups. Experimental and university groups used techniques ranging from ballet to Stanislavski’s system to devise adaptations of works by popular Latin American poets like Gabriela Mistral and Nicolas Guillén. This was also the time when poet Pablo Neruda’s only play The Gleam and Death of Joaquín Murieta (El Fulgor y Muerte de Joaquín Murieta, 1966) was first produced. It tells the story of a Chilean folk hero who travels to California in the late 19th-century Gold Rush. The ‘Yankees’ mistreat Joaquín in the mines and rape and murder his beloved wife, Teresa. Joaquín becomes a bandit and with his gang steals the Yankees’ gold. Joaquín is ambushed and shot when he visits Teresa’s grave. The Yankees then charge the public a fee to gaze at his decapitated body. This story is told in six scenes through a mixture of verse narration, choral interludes, prose dialogue, and song. Joaquín only appears once in the play, after his death, when his head begs Pablo Neruda to sing for him. In his preface, Neruda says: ‘This is a tragedy, but it is also partly written as a joke. It seeks to be a melodrama, an opera and a pantomime.’ Neruda says the inspiration for the play was a funeral scene he saw in a Noh play, adding: ‘I never had any idea what that Japanese play was about. I hope the same thing happens to the audience of this tragedy.’

1980-1996

Most of Latin America embraced liberal democracy in the 1980s and 1990s, and by 1996 only Cuba remained outside this political fold. Some theatre practitioners could not cope with the new pluralism after years of rigid regulation. Those who had harboured hopes of popular revolutions despaired as socialism crumbled in Eastern Europe. Other dramatists used the changes and actively supported democratisation, usually by turning theatrical spotlights onto the horrors of past military dictatorships, a trend exemplified in Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden (La Muerte y La Doncella, 1991), a film version of which was directed by Roman Polanski in 1994.

Thematic concerns shifted with the times. Issues such as class conflict, military oppression, revolution, and US imperialism no longer excited dramatists as they had done in the 1960s and 1970s. The focus moved from the socio-political to the inter-personal, concentrating on themes of sexuality, gender, personal identity, and the influence of the mass media, as reflected in the plays by Fuentes and Vargas Llosa in this volume.

Carlos Fuentes was born in Mexico City in 1929, grew up in Washington DC and studied at universities in Mexico and Switzerland. He is an extraordinary polymath: a highly acclaimed novelist, writer of screenplays, editor, historian, political thinker, teacher and ambassador for his country. The first of his three plays, All the Cats Are Lame (Todos los gatos son pardos, 1970), is a complex socio-historical portrayal of the Spanish invasion of Mexico, revolving around the conflict between the Aztec leader Montezuma II and Hernán Cortés. The Blind Man is King (El Tuerto es rey, 1970) concerns a blind lady and her blind servant, who await the return of the lady’s husband, both of them terrified that the other has sight. The third play, Orchids in the Moonlight, is a stunning portrait of the intricacies of human fantasy and the impact of the moving image.

Mario Vargas Llosa was born in Arequipa, Peru in 1936. He spent his first ten years in Bolivia where his grandfather was a diplomat, and later studied law at the University of San Marcos in Lima. Like Paz and Fuentes, he has many professional identities: novelist, critic, essayist, TV journalist, and Peruvian presidential candidate. He has written five plays to date. No copy survives of El Inca, his first play which he wrote while studying in Peru. His second, written some 25 years later, is The Young Lady from Tacna (La Señorita de Tacna, 1981), a dramatisation of the process of storytelling. It was followed by Kathie and the Hippopotamus (Kathie y el Hipopótamo, 1983), a comedy about a Parisian housewife who hires a writer to record her invented memories. Mistress of Desires was written two years later. Finally, The Madman of the Balconies (El Loco de los Balcones, 1993) tells the story of an old professor whose obsession with preserving the colonial balconies of Lima drives his beloved daughter to desert him – an interesting parallel to the storyline of Paz’s Rappaccini’s Daughter.

The self-searching that preoccupied dramatists like Vargas Llosa and Fuentes in the 1980s and 1990s marked a change in the nature of ‘autonomous theatre’. The use of anthropology as a method of exploring both personal and cultural identity proved to be a rich new source of inspiration. This was encouraged by the activities of three European-based institutions: Eugenio Barba’s International School of Theatre Anthropology which was founded in Denmark; Jerzy Grotowski’s Laboratory Theatre in Poland; and Peter Brook’s International Centre of Theatre Research in France. Many Latin Americans read about, or worked at, these establishments, and then developed their own related ideas. The Cuban theatre group Teatro Buendía places anthropology at the centre of its rehearsal method. During its investigation of the Afro-Cuban religion of santería, the group found that the rhythms of the batá drums, which santería believers consider to be the intermediaries between the human and the divine, can induce a state of trance. The group now uses trance as a preparation technique for creating a form of theatre that is both in close contact with its own cultural roots and which can communicate successfully across national boundaries, as demonstrated in the critical and public acclaim that greeted its tours in Europe and the Far East in the 1990s.

A few of these anthropological projects have resulted in written texts. The Mexican Compañía Nacional de Teatro collaborated with the playwright Sergio Magaña to record The Enemies (Los Enemigos, 1990). This extraordinary text portrays the attempts of the 19th-century priest Charles Brasseur to stage the Rabinal Achí. The story begins just after Brasseur’s first transcription of the piece from oral tradition. Proud of his work, Brasseur wants to see the play staged in an ‘authentic’ way, as opposed to the folkloric representations of the time. The Indians refuse to participate until he agrees to pay them and to allow the performance to be staged in the nave of the local church. The Indians then perform an ‘authentic’ version of the Rabinal Achí, which ends in the actual sacrifice of the actor playing the Quiché Warrior on the church altar. Appalled by what he has done, Brasseur flees the village while the locals honour the sacrificed actor. The production was based on extensive anthropological research into the dress, music, dance and gestural languages both of the 19th century and of the Rabinal Achí itself, and on European understanding and portrayal of the Mayans. The story was told through the eyes of Brasseur, a European, so that the rituals took on an exotic and primitive quality. For the mainly Mexican audience, it was only ‘authentic’ in the sense that it depicted the ways Europeans perceived indigenous cultures.

Some of the work that has come out of anthropological research can be properly described as ‘post-modern’. Post-modernism, according to Jean-François Lyotard who coined the term, means a sceptical attitude towards overarching explanations of the world. In the theatre, this scepticism is directed at any universalising theories of drama, such as the Christian or socialist suggestions that theatre should be used as a tool for social change, or the Aristotelian notion that effective drama can only be produced if the unities of time, place and action are maintained. Post-modernism is also characterised by linguistic playfulness and by referentiality, which tends to mean multiple quotations from other texts, genres, and from the works themselves. A good example of a post-modern Latin American play is Timeball (1991) by the Cuban Joel Cano. This mosaic-like work shows radical scepticism towards theatrical norms. Instead of a logical narrative progression, there are 52 scenes which must be ‘shuffled’ before each performance, so that they will always be presented in a different order. Cano describes this genre as ‘theatrical fortune-telling’. The play contains many cultural references, including ‘appearances’ by Charlie Chaplin, John Lennon, Lenin, and Marilyn Monroe. Cano also expresses an ironic attitude towards the dramatic unities, setting the play in 1933, 1970 and ‘no time’, and alternating the action between a stable, a park, a circus and a stadium.

In the 1990s Latin America once again flourishes as a rich seedbed for exciting new plays; but the region’s theatre also faces enormous problems. As in most parts of the world, no problem is more acute than the shortage of funding. In the 1980s and 1990s, governments cut back finance for the theatre, especially for training. It is difficult for a Latin American playwright to make a living as runs are short, and revenues divided many ways. Financial temptations lure many good writers into television and to richer pastures in Europe or the USA. In addition, Latin American audiences remain generally conservative in their tastes, and a playwright devoted to non-commercial or ‘autonomous’ theatre always risks alienating the very people whose material support he depends on. Economic self-censorship has, at the end of the 20th century, taken the place of the almost extinct direct political censorship of the theatre.

Selecting and Translating the Plays

The five plays included in this book may all be described as being within the tradition of autonomous theatre. Their principal characters express a desire for freedom and a spirit of resistance to oppressive authority: Lalo in Night of the Assassins and Beatrice in Rappaccini’s Daughter share a yearning for a life outside the suffocating confines of their homes; La Chunga in Mistress of Desires and Dolores in Orchids in the Moonlight bravely search for dignity in the face of violent male chauvinism; and the Man in Saying Yes strives to overcome his cowardice and passivity and to confront the hairdresser’s callousness. Although the characters often fail tragically in their bids for freedom, they encourage the belief that we are all capable of changing our lives for the better if we overcome fear.

The playwrights make bold formal choices, some of them remarkably similar. They all reject straightforward naturalism, and they avoid a linear narrative in favour of broadly circular structures, so that in every play the ending mirrors the beginning in some way: the Boys repeat their ritual song at the end of Mistress of Desires, the Hairdresser is reading his magazine again in Saying Yes, the Messenger re-addresses the audience in Rappaccini’s Daughter, Beba prepares to lead a new game in Night of the Assassins, and Dolores repeats her opening complaint in Orchids in the Moonlight. Such endings resolve nothing, and the writers run the risk that their audiences will accept the ambiguities left at the end at face value; yet such ambiguities provide audiences with questions that they must try to answer for themselves in order to finish the plays: Where is Meche? Are Maria and Dolores awake or dreaming? Does the antidote kill Beatrice or release her into the outside world? Could the siblings really kill their parents? Why does the Hairdresser kill the Man? The plays also have certain images in common, particularly those of the mirror and the labyrinth. Labyrinths feature in all the plays except Saying Yes, and have fascinated Latin American writers stretching back to Sor Juana and her secular comedy Love is the Greater Labyrinth (Amor es Más Laberinto, 1688).

The plays are also individually distinctive in many respects. Their sources, language, and action are as individual as the writers themselves. Moreover, since each play was written at a different time during the second half of the 20th century, each reflects the social and political concerns of its particular moment. Rappaccini’s Daughter mirrors the terror of technological progress and the nuclear threat that stalked the 1950s; the 1960s hope of revolution is a principal theme of Night of the Assassins; the political violence and global terrorism of the 1970s provides the dark backdrop to Saying Yes; and social scientists, writers and film-makers were exploring issues concerning personal identity and sexuality when Orchids in the Moonlight and Mistress of Desires were written.

The starting point for translation of the plays was always the individual words, and they have been translated as transparently as possible. The translation of Spanish poetry in the plays treats the word as more significant than the rhyme or metre: this is especially reflected in Rappaccini’s Daughter and in the blank verse translation of Sandoval y Zapata’s sonnet in Orchids in the Moonlight. Words which are peculiar in the original Spanish, moreover, are translated that way into English, as in the use of ‘marmots’ in Saying Yes, or in Catholic expletives like ‘Holy Whore!’ in Mistress of Desires.

The English versions have benefited enormously from being read and amended by the playwrights themselves, all of whom are familiar with the English language. The authors’ insights have helped ensure accurate renderings of the actual Spanish words, which also echo the intentions behind the original texts. Mario Vargas Llosa, for example, explained that the name La Chunga refers to a strong, lower-class woman in 1940s Peru; while discussions with Carlos Fuentes excavated many of the cinematic references in Orchids in the Moonlight.

Sometimes a literal translation cannot convey a sound or rhythm essential to the original. In these cases, alternative choices have been made, retaining associations to the original. This ‘associative’ approach was taken in the translation of the Boys’ song in Mistress of Desires, and in the allusions to nursery rhymes in Night of the Assassins. The actual staging of the plays was always viewed as an integral part of the translation process, and production has enriched all these texts. Hearing the words onstage opened the way for a greater immediacy in the translation.

Select Bibliography:

J.J. Arrom, Historia del Teatro hispanoamericano: época colonial, Mexico, 1967; P. Beardsell, A Theatre for Cannibals: Rodolfo Usigli and the Mexican Stage, London & Toronto, 1992; W. Benjamin, Illuminations, Fontana, 1992; Raul H. Castagnino, El Teatro de Roberto Arlt, Buenos Aires, 1964; F. Colecchia & J. Matas, Selected Latin American One-Act Plays, Pittsburg, 1973; Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, Obras Completas, Mexico, 1992; W.K. Jones, Behind Spanish American footlights, Austin, 1966; Latin American Theatre Review; New Theatre Quarterly; R. Leal, Breve Historia del Teatro Cubano, Havana 1980; O. Paz, Sor Juana or The Traps of Faith, Harvard, 1988; C. Solorzano, El teatro latinoamericano en el siglo XX, Mexico, 1964; D. Taylor, Theatre of Crisis: Drama and Politics in Latin America, Kentucky, 1991; R. Unger, Poesía en alta voz in the Theatre of Mexico, Missouri, 1981; A. Versényi, Theatre in Latin America, Cambridge, 1992.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to numerous people for their support and assistance over this four-year project. I am especially grateful to the playwrights for their advice and collaboration on the translations and stagings.

Many thanks also to a number of people who gave generously of their time to read and make suggestions on drafts of the text, particularly Kate Berney, Caroline Voûte, Mark Hawkins-Dady, Catherine Boyle, Montserrat Guibernau, Tilly Franklin, William Brandt, Tom Hiney, Gaye Wilkins, Jeremy White, Eliot Weinberger and Zoë Crawshaw.

In addition, I am indebted to all the performers, designers, musicians, producers and technicians who channelled their creative energies into the staging of the plays and brought them to life in the process. I am also deeply grateful to those institutions and individuals who provided the material resources for the productions, especially Tony Doggart, the Southern Development Trust, Drama King’s, the Gertrude Kingston Fund, the Esmée Fairbairn Trust and Ann Toettcher.

Thank you, finally, to all those who gave encouragement and inspiration of a personal nature particularly Jane Toettcher, Dadie Rylands, Rupert Gatti, Susan Melrose, Graham McCann, David Lehmann, Nike Doggart, Hugo Jackson, Flora Lauten, Carlos Celdrán and Natalia Gil Torner.

This book is dedicated to my parents and grandparents.

S.D., May 1996

RAPPACCINI’S DAUGHTER

by Octavio Paz

La Hija de Rappaccini was written in 1956. This translation of Rappaccini’s Daughter was first performed at the Gate Theatre, London on 21 January 1996, with the following cast:1

MESSENGER

Gabrielle Jourdan

ISABELA (an old servant)

Kay D’Arcy

RAPPACCINI (a famous scholar)

Kevin Colson

BEATRICE (his daughter)

Sarah Alexander

BAGLIONI (a university doctor)

John O’Byrne

GIOVANNI (a student from Naples)

Jud Charlton

Director Sebastian Doggart

Designer Tom Harrison

A one-act play, based on a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

To Leonora Carrington

Prologue

The garden of DR. RAPPACCINI. At one side, part of an old building where GIOVANNI’s room is. The stage is set so that the audience can see inside the room: tall and narrow, a large mirror covered with dust, a desolate atmosphere. Flanked by worn curtains, a balcony opens on to the garden. A magical tree stands centre stage. As the curtain rises, the stage remains in darkness, except in the space occupied by THE MESSENGER, a hermaphroditic character dressed like one of the Tarot figures, though not any particular one.

THE MESSENGER. My name does not matter. Nor does my origin. In fact, I don’t have a name, or a sex, or an age, or a country. Man or woman; young or old; yesterday or tomorrow; north or south; the two genders, the three tenses, the four ages and the four cardinal points converge in me and in me dissolve. My soul is transparent: if you peer into it you will sink into a cold and dizzy clarity; and you will find nothing of me at the bottom. Nothing except the image of your desire, that until now you did not know. I am the meeting place; all roads lead to me. Space! Pure space, null and void! I am here, but I am also there; everything is here, everything is there; I am at every electric point in space and in every charged fragment of time: yesterday is today; tomorrow, today; everything which was, everything which shall be, is happening right now, here on earth or there in the heavens. The meeting: two gazes which cross until they are no more than a glowing point, two wills which entwine and form a knot of flames.

Unions and separations: souls that unite and form a constellation which sings for a fraction of a second in the centre of time, worlds which break up like the seeds of a pomegranate scattered on the grass.

Takes out a Tarot card.2

And here, at the centre of the dance, as the constant star, I have the Queen of the Night, the lady of hell, who governs the growth of the plants, the pull of the tides and the shifting of the sky; moon huntress, shepherdess of the dead in the underground valleys; mother of harvests and springs, who sleeps for half the year and then awakes resplendent in bracelets of water, sometimes golden, sometimes dark.

Takes out two cards.

And here we have her enemies: the King of this world, seated on a throne of manure and money, the book of laws and the moral code lying on his trembling knees, the whip within his reach – the just and virtuous King, who gives to Caesar what is Caesar’s and denies the Spirit what is the Spirit’s. And facing him the Hermit: worshipper of the triangle and the sphere, learned in Chaldean writings and ignorant of the language of blood, lost in his labyrinth of syllogisms, prisoner of himself.

Takes out another card.

And here we have the Minstrel, the young man; asleep, his head resting on his own childhood. He hears the Lady’s night-time song and wakes. Guided by that song, he walks over the abyss with his eyes shut, balancing on the tightrope. He walks with confidence in search of his dream and his steps lead towards me, I who do not exist. If he slips, he will fall headlong. And here is the last card; the Lovers. Two figures, one the colour of day, the other the colour of night. Two paths. Love is choice: death or life?

THE MESSENGER exits.

Scene I

The garden remains in darkness. The room is lit by a dim light; the balcony curtain is drawn.

ISABELA (comes in and shows the room). We’re here at last, my young sir. (Reacting to his dispirited silence.) It’s years since anyone has lived here, which is why it feels abandoned. But you will give it life. The walls are strong . . .

GIOVANNI. Perhaps too strong. High and thick . . .

ISABELA. Good for keeping out the noise from the street. Nothing better for a young student.

GIOVANNI. Thick and damp. It will be hard to get used to the damp and the silence, though there are some who say thought feeds on solitude.

ISABELA. I promise that you’ll soon feel at home.

GIOVANNI. In Naples my room was big and my bed was as tall and spacious as a ship. Every night when I closed my eyes, I sailed over nameless seas, unsettled lands, continents of shadow and fog. At times, I was frightened by the idea of never coming back and I saw myself lost and alone in the middle of a black ocean. But my bed slid with silent certainty over the crest of the night, and every morning I was deposited on the same happy shore. I slept with the window open; at daybreak the sun and the sea breeze would spill into my room.