Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Book translated by Lola Rogers. Mexico City - Autumn 2004. A Nordic filmmaker arrives in the city to make a documentary about a major architectural landmark - Luis Barragán's Casa Estudio house. He meets a Mexican woman who opens a totally new door into the world of the Russian Jewish ex-communist leader Leon Trotsky, who was murdered in Mexico in August 1940. The encounter sends the filmmaker on an extraordinary journey into an entirely new aspect of the most mistreated political figure of the 20th century and his philosophy. The novel is also an exceptional love story set in an era when the concept of time has lost its original meaning and climate change is just an unpleasant possibility.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Rax Rinnekangas is an author and film director. His most recent works include Mestarin viimeinen toivomus (Master’s last wish, 2019), an essay of reading three times The Brothers Karamazov of Dostoevsky in a monastery, and Nocturama: Sebaldia lukiessa (Nocturama: Reading Sebald, 2013), an account of experiencing the literature of W.G. Sebald and the works of Peter Handke, Thomas Bernhard, and Imre Kertész, authors of the same spiritual circle. In his art films, Rinnekangas has examined architecture, visual art, and social themes. Two North(s) & a little part of anywhere, a collection of his six feature films with the music scores by Pascal Gaigne, a French-Spanish composer, was published in 2018 and is distributed by Quartet Records (Spain), one of the world’s leading publishers of the cinema music. American streaming service Kanopy distributes his architecture films. He has published photographic works on subjects such as Europeanism and the Holocaust and had 60 private exhibitions in various countries (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, 2003, Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, 2007). His literary works have been published in France, Germany, and Spain: La lune s’enfuit, Editions Phébus, France, 2011; Le juif égaré, Editions Phébus, France, 2013; Der Mond flieht, Graf Verlag, Germany, 2014; La Partida, El Desvelo Ediciones, Spain, 2010; La Luna se escapa, El Aleph Editores, 2012; Adana, El Desvelo Ediciones, Spain, 2019. His works have received numerous awards, including the Finnish State Prize for Literature, the Finnish State Prize for Photographic Art, the Honoured Jury Prize of the International Festival of Films on Art (FIFA), Montreal, the Alex North Prize, Spain. Leon Trotsky’s Stopwatch describes the evolution of the most misunderstood great figure of the early 20th century and portrays the Jewish politician, philosopher, and advocate for world-wide equality who was assassinated in Mexico in 1940 with a different aura than the one the early Stalinist world wanted to give him. It’s also a different love story at a time when the concept of time has lost its original meaning.

Compilation of visual material was supported by a travel grant from the KIDE Center for Literature.

Quotes from W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz are translated by Anthea Bell, W.G. Sebald: Austerlitz (Random House, 2001).

Quotes from Leon Trotsky’s Testament are translated by Elena Zarudnaya, Trotsky’s Diary in Exile, 1935, Faber and Faber, 1958

Quotes from Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet are translated by Lola Rogers from Sanna Pernu’s Finnish translation Viisas elämä, 2016.

Quotes from Imre Kertész’s Galley Diary are translated by Lola Rogers from Outi Hassi’s Finnish translation Kaleeripäiväkirja, Otava, 2008.

Quotes from Kahlil Gibran’s “On Children” are from his 1923 collection The Prophet.

© Rax Rinnekangas

Originally published as Leo Trotskin ajastin, LURRA Editions, 2018

LURRA [email protected]

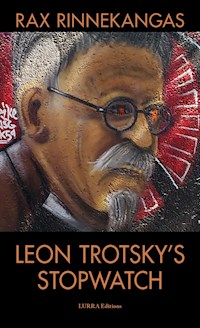

Cover image by Rax RinnekangasImage of Rax Rinnekangas by Leena LouhivaaraCover and layout by Kim Söderström

ISBN: 978-952-7380-15-4

”Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it.”

William Shakespeare

THE CODE

1.

That autumn, at the beginning of humanity’s final century, when humankind was at long last finding the courage to acknowledge the dramatic change that had occurred in the planet’s climate and I had travelled to Mexico to shoot the last film of my documentary series, I had as yet no idea of the extent to which humankind’s conception of its entire history was based on the same sort of cowardice. Hand in hand, with eyes closed, we were living a collective lie buttressed by our need to see our history, its central figures and the factors that influenced their fates in a concrete light, to the exclusion of their more equivocal psychological intricacies. I was also unable to conceive of the idea that almost as soon as I had arrived in Mexico City I would encounter real lions. Up to that point I had thought, like many people, that almost all of the lions left on the planet were living in captivity in the numerous zoos of the Western world, and that any remaining wild lions were wandering somewhere on the African savannah, where very rich people went to secretly hunt them so they could mount their heads on the walls of their mansions. I’d seen, of course, the documentary about the shameful treatment of perhaps the proudest creatures in all creation. In certain African countries there were centers run by parasitic humans, black and white, where clones were made from lions abducted from the wild, and anyone with an interest in violence and animal torture could go there to kill them, for a large fee. But the idea of absolutely real, living lions in the garden of a middle-sized, two-story, Spanish-style hotel in the Tacubaya neighborhood of Mexico City had never entered my mind.

The hotel was a hacienda-style compound and I was staying for three weeks in a room in one of its annexes. My window opened directly onto a lush garden covered in foliage and intersected by a little gurgling brook with the hotel restaurant on the other side, and between the brook and the restaurant’s outdoor tables were the lions, living in two connected steel cages. There were two lions—an elderly female and a young male. Golden brown, quite muscular under the circumstances, thoroughly noble and unconcerned in spite of their living conditions, they lay behind their bars as if in some twice-removed reality, or walked unhurriedly from one cage to the other casting indifferent glances at the hotel guests, who sat about ten meters away at their breakfast tables marveling at the presence of these animals, until they grew accustomed to them and became absorbed in their meals. In the darkest hours of night I heard strangled-sounding roars that made it seem as if I were sleeping at the edge of a jungle in some small African nation.

I didn’t really wonder much at the arrangement – I was in Mexico now, after all. With each meal I watched these enigmatic animals, whose invisible mental state and visible physical state impressed me above all in a moral and emotional sense because, for one thing, in any other country keeping lions in a cage in a hotel garden would almost certainly be prohibited. But not in Mexico. It was a country where ancient and indivisible self-interest and the individual right to enjoyment still reigned and legislative oversight by the corrupt government was a mere formality. The ones with actual rights were the aristocratic upper classes, and on another, more dire level el cartel de la droga, whose members divided the large country into their own personal dominions beginning at the southern border of the United States, slaughtering each other pitilessly and in the process murdering innocent bystanders with increasing frenzy and, by these openly genocidal acts of public terrorism which reached across both Americas, achieved an annual economic output greater than that of the entire country of Mexico. The right of the family who owned the hotel to have openly kept, for some unknown reason, ten or more African lions, one after another, in their idyllic hotel garden, is an example of how far an individual’s idea of his rights could be taken in that country.

I spent all my early mornings and many of my evenings near the lions as I ate my meals in the garden, which made me even more sensitive than usual to the progression of thoughts I found myself in. I watched the animals’ proud and self-assured figures in the steel cage prison that made it impossible for them to turn around more than twice in its ten square meters, let alone exercise all their natural need to run free and hunt, which must have caused them horrible suffering, and in those hours of deep anguish I imagined them in their true home on the African savannah with its grasses and trees, from whence they had been taken by some dark route of civilization to this prison, a fact they outwardly seemed to accept, but which they couldn’t for one second forget in this occult ritual where they performed the part of unending dignity for the audience of hotel guests, a role they had mastered as Homer’s Odysseus had when trapped in the cave at the hands of the cyclops Polyphemus. I saw the lions as thinking, creative individuals, and as I observed the demeanor of these creatures imprisoned in their cages I pondered all of humanity on our planet and all their wrongheaded ideas, the creative individual’s state of simultaneous imprisonment and liberty under those circumstances, the fact that even if our political reality represses spirituality, consciously and unconsciously ignoring the significance of the creative individual in the development of society, both creativity and its suppression have nevertheless always been essential to the birth of local identities, including Mexico’s, through a litany of names spanning the cruel and bloody history of the formation of the country: Porfilio Díaz, Émiliano Zapata, Lázaro Cárdenas, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Fernando Leal, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera... It was through the joined, bloody hands of the soldiers and politicians and artists who made revolutions that the Mexican people’s concept of its identity was born, its national imagery, its citizens’ sense of home. The latter, in a broader sense, was part of the reason I had begun my documentary project.

With the help of an architect friend I had chosen five private homes in different countries and on different continents that represented the architectural peak of 20th century modernism. Through the physical and psychological substance of the houses and their designers’ signatures I would, in the resulting documentary series, give a complete picture of the approach to architectural language and the concept of home in different cultures and language areas. The chosen houses were in central Moscow in Russia; outside the city of Ashiya in Japan; on a steep, narrow spit of land in the bay at Monaco; in my home country of Finland; and in Mexico. After a phase of preparation that lasted a year, I had obtained permission to film in all the houses, and funding from various sources around the world, and I had completed shooting in all of the destinations except Mexico City, where the project had now led me for the second time.

Before I began filming the final installment in the series, whose subject was located near my hotel in the Tacubaya neighborhood, I held a week-long workshop at a private film school in the southern part of the central city. There were about sixty students in the course, widely ranging in age and nationality. For five days I lectured on the film language represented in my work and my conviction that a film image of even one minute’s duration, whether fictional or documentary, is something completely different from the mere pictorial surface that strikes the eye. An image is not just an image but also a multi-layered code system that must be deciphered and understood in the same way that we decipher, interpret, and understand multi-layered literature, and I showed the class various shots from my films as examples and had heated discussions with the class about my vision. It was all the usual ego-stroking and helpful interaction with my students to which I’d grown accustomed in various workshops in various countries over the years. But then, at the end of the last day of the course, the whole meaning of the class, as well as the whole direction of my life, changed quite unexpectedly when a woman of about forty, black-haired, tall and erect, stepped forward from the back of the lecture room and asked if she could show me her photographs.

That evening after the final film showing we met in the school’s cafeteria and she—Veronica Díaz, originally from Spain, a woman shot through with suppressed sorrow, as I sensed from the first moment I saw her, and confirmed later—opened up a leather portfolio she’d brought and laid before me a series of black and white photographs she had taken on a prison island in the Pacific. She told me about her numerous visits to this place which housed very dangerous criminals, most of whom would never get out from under their sentences, but it did allow the prisoners to bring their spouses and families if they were prepared to live in such a circumscribed reality. Veronica Díaz described at length and in great detail this experimental prison, run by the Mexican government and located in the open sea over a hundred nautical miles southwest of the country’s western coast. The island was Mexico’s own Alcatraz, a dumping place for the most vicious criminals, first sentenced to forced labor, then moved to paradise, as it was generally called, with the rationale that there was no reason to deprive them of their ordinary living arrangements and that some of them, having suffered through part of the sentence that the laws of society demanded, might if shown mercy return eventually to a normal life. With that in mind, there were no cells or bars on the island, and its inhabitants, who were called settlers, didn’t wear prisoner’s clothes. They lived like normal people in little houses on sunny streets like those in any small town in Mexico. The naval forces stationed on the fifty-square-mile island carried guns, but the prison guards did their work unarmed. The children of the prison, of which there were some six hundred, lived with their parents and went to school at various places on the island.

”Before they started calling it paradise, it was called the hell without walls,” Veronica Díaz said. ”And the prisoners were treated cruelly. But then everything changed.”

It is now like no other prison in the world. Mexico’s annual budget for this two-thousand prisoner paradise was many times more than what was used to maintain ordinary prisons, but the investment was considered justified. While elsewhere in the country the status of prisoners was very weak due to the cruelty perpetrated by the guards, on the island the idea was to transfer the power from the guards to the prisoners themselves so that they would learn to take responsibility in all the ways one does in normal life. The method worked well; two thousand criminals categorized as dangerous were watched over by fifty guards. Veronica Díaz also told me about the dark side of the island. The attitudes of the children and young people, living in paradise for what felt like forever because of the sentence of a parent or parents, were sharply divided. Some of them enjoyed being on the island and in due course even married a prisoner, creating a new foundation for their entire reality and their future, while others learned bad habits, having never known any others, and many of the prisoners, though aware of their extremely privileged position in the national penal system, experienced the sea around them as endless prison bars whose presence wasn’t erased by their freedom of movement on the island or the patch of garden they tended or their evenings spent partying at the island dance club. The human mind furnished with the freedom of this sort of imprisonment recognized its constructed boundaries, which were strengthened by the knowledge of the reasons that they and their loved ones had ended up on a remote island, utterly removed from the entire normal world of people. As I listened to this head-spinning yet plainspoken account I couldn’t help thinking of certain very different prisoners I knew, at least superficially—the two caged lions in the idyllic garden of my hotel.

Veronica Díaz was a very beautiful, peculiar woman. There have been times in my life when I would have been instantly flummoxed by meeting someone like her and my mind, flung into a deep emotional state, would have immediately started to make plans with results that wouldn’t bode well for me. But now, watching and listening to Veronica Díaz—her fixed, sorrowful gaze, the thin layer of freckles on her thin, bony face framed by long, copper-black hair—I felt no fear, only interest, and trust, for some reason. During pauses in her story she showed me the series of photos she’d taken on her many visits to the island over the years.The black and white images didn’t impress me artistically—they were quite ordinary reportage photographs—but the eyes of the people in the photos touched me. They were men and women of many different ages, all of them dangerous criminals and all, without exception, seemed filled with vitality and emanated a powerful self-respect. When I asked who was who in one picture or another, and what each had done to earn their long sentence, Veronica Díaz answered, ”This young man worked as a heroin mule from the age of fifteen, before his murders...” ”This woman shot four people coming out of a post office...” ”This old man killed two women in a drug store and wounded seven on the street outside...” ”This young woman stabbed her mother with a knife and shot her father...” She said all these things very calmly, as if she were speaking of long-settled matters in the fundamental legal arrangements of life.

When we came to a photo of a somewhat thin-looking man, black-haired, about fifty years old, with a slightly hooked nose, she was at first silent when I inquired about his identity and the specifics of his crime. But then she answered, ”I’ve never learned precisely—perhaps for him it was all one big, slowly growing error.” As she spoke she stared straight ahead, as if bringing the matter to a close, and turned to the next photo. But I wasn’t looking at the rest of the photos very carefully. My mind was stuck on something that I felt within my body like a touch, caused by her words and the look in her eyes—that not only was the man in question, sentenced to life in prison, still a part of the photographer’s life in some way, but that this woman in the film school cafeteria also bore a particular sorrow concerning him.

Without either of us actually suggesting it, we took long walks in different parts of the Centro Historico over the next two evenings. We didn’t talk about the photos of the prison island on either of these walks, because I had already sincerely expressed the deep impression her photographs had made on me, and that seemed enough for her. We also didn’t discuss the contents of the workshop I’d given. I felt however that it was the experience of taking my course that had made this serious and unusual individual come from the back of the lecture hall to talk to me. That knowledge was enough for me. I didn’t need recognition of my filmmaker’s language or want to pry any further about her relationship with the man in the photograph. I simply enjoyed her presence and her aspect and her stories. I also sensed that our unexpressed need to spend time together was due to some entirely different cause. I could feel that there was some factor in our natures that bound us together in an invisible way.

On both evenings we began by visiting the Palacio de Bellas Artes to look at large paintings by famous Mexican artists, and both times we lingered in front of Rufino Tamayo’s Birth of Our Nationality, as if the fate of the Mexican people depicted there, the bloody victims of chaotic Spanish colonialism, caught in the rapacious grip of Western conquerors and Western culture, the cosmic colors, dynamic forms and harsh symbolism in the nearly seven-square-meter painting touched us particularly, especially now that there was a peculiar sense of expectation quivering between us, a feeling I interpreted as not physical so much as spiritual. On both visits we examined the painting’s many elements and colors in great detail for about half an hour, discussing our impressions, before moving on to the other paintings in the museum. When we left the Palace of Fine Arts we walked through the city’s busy streets, then sat for a long while on a stone bench at the edge of Zocalo Plaza and looked at the

people crossing the vast square and the dark, rugged height of the cathedral looming before us, planes soaring behind it like slow, black bats every two minutes toward Benito Juárez International Airport, and on both hot evenings we also went into the church to light candles to the unknown departed and then sat for a little while in the cafe of the American bar on Cinco de Mayo street before parting at the edge of the square in front of the metro station, where I caught a taxi for the seemingly endless one-hour drive from the city center back to my hotel on the other side of the Bosque de Chapultepec.

As I sat later at my dinner in the hotel garden watching the lions, who were more and more familiar as the days passed, the warm evening was filled with an unnatural-seeming climate of cedars and oaks and ornamental flower beds and steel cages, and I felt the same emotions I’d had two years before when I’d opened a collection of essays in a bookstore in Brooklyn, New York. In the pages of that book, having recently pondered universal concepts of home for the first time, my eye was caught by a certain passage in which the author of the work, the German writer W. G. Sebald, ponders the illogic of the gigantic fortresses built in Belgium in previous ages and ends his musings with this sentence: ”Such complexes of fortifications... show us how, unlike birds, for instance, who keep building the same nest over thousands of years, we tend to forge ahead with our projects far beyond any reasonable bounds.” The reference to the saintly-seeming humility of winged birds, their consciousness of the actual size of one of the basic needs in their lives, compared to humankind, wingless yet endlessly dreaming of wings of their own, their greed ever-increasing even with regard to their own dwelling places, made me realize that instead of the single film I’d been planning I should make an entire series of separate films about masterpieces of residential architecture in different cultures and on different continents, the homes of those who were, in their own lifetimes, very successful and cultured people, clients who granted their architects creative freedom and counted themselves among the chosen few when it came to houses. My documentaries would examine, as I said, not just the architectonic elements of the houses and their approach to the concept of home but also the history of the concept of home, including such oddities as the ability of a certain persistently persecuted Pakistani tribe to carry their home with them, a sacred place symbolized by a short wooden pole around which these hounded people could gather no matter where they were in their fugitive travels and experience being both at home and in a shrine, a concept of home also represented, in Mozambique at least, by the minority language they spoke. My film series had its impetus in that moment with W. G. Sebald’s text. Now I was filled with the same emotion without being able to explain the germ of it to myself except to think that it all must have started with meeting Veronica Díaz.

We met for the third time on a Sunday, the day before I was to begin shooting my documentary. A thick mass of smog hovered like a layer of false age over the vast, dried-up lake, a plateau above the metropolis, and we escaped that aged city center on the crowded metro—a quarter-hour trip to a little town in the district of Coyoacán, where we passed the time with leisurely wandering in the market squares and enjoyed cocktails on a terrace somewhere amid an unending blare of trumpets, surrounded by crowds dressed in national costume and other colorful clothes, then took a long walk in hushed older neighborhoods filled with upper-class villas until, in the Colonia de Carman, we found ourselves near a cobalt-blue wall, at a railing lined with old American and European cars and an endless queue of travelers winding its way like an eel toward the entrance, as it did every weekend as soon as the house opened to the public. In every place we had been we found ourselves looking at each other every now and then just for a moment and acknowledging that, for some reason, beneath the trust and delicacy and magic we felt there was also a familiarness in being together, which would later make sense to me. We spent about an hour at Casa Azul, Frida Kahlo’s birthplace, a ten-room building of nearly a thousand-square-meters with rustling gardens and a second floor that contained something more than the emptiness reported in the literature and media of the world. But once again the occultism in her interior design, the works on display in many rooms by artist friends of Kahlo such as Joaquin Clausell, José-Maria Velasco, Mardania Magaña and Paul Klee, and the saturated colors of Kahlo’s works, above all the conscious insanity and lack of restraint with which she used the color yellow—a color that had in ancient China been banned from use among ordinary people because it represented the perfect color of the sun, the universe, and the heavens, and could thus only be used by the rulers, considered in later, Christian works of art as the color of deception, Judas’s color, and in the middle ages was the very color that the catholic church required Jews to wear, as did the Nazis later still, christening yellow the representative color of all the evil of the Jew—made the same strong impression on me that they had on previous visits.

We examined the details of the interiors of the Blue House with great care, as if by doing so we could prolong the effect we were having on each other—ceramic pots and other objects, the model for the plaster corset that Kahlo had to wear for her injured back, the painting of the dead child over the bed and below it the photo collage showing Lenin, Marx, Engels, and Mao Zedung as well as Stalin, whom Kahlo had taken a sudden liking to, dictatorship and all. But while we walked through the house, the living room where Eisenstein, Gershwin, Dolores del Río and Rockefeller had enjoyed the company of Frida Kahlo and her communist husband Diego Rivera, who had his own house was on the other side of the same lot, and discussed the house’s classical style of construction and decoration, the interiors and objects and artworks of the smaller rooms filled with the trademark necklaces and Tehuana-style folk costumes of the mistress of the house, I was aware above all of Veronica Díaz’s presence and was thinking of something else entirely—the homes on that monastic island, where an out-and-out criminal could, if he had the strength, experience the grace of self acceptance.

For a moment I couldn’t imagine in all the world a better place to humble the human psyche than the prison island. No matter what the culture, the one central reason for shutting oneself up in the heavenly earthly home of a monastery is a need to submit oneself for the rest of one’s life to a prolonged struggle on the spiritual, physical and mental planes. And the task of these chosen dangerous criminals was to experience a similar struggle in their heavenly home in the sea. While humanity on every continent, in places where the demonic colonizer Consumption had established itself as a religion of house and home, prayed without ceasing to someone On High for a feeling of security, that very feeling was granted to perpetrators of homicides and other horrendous acts in the form of self-examination and the presence of their loved ones for the rest of their lives, if they but wished it. The result might be considered a condition of ideal inner happiness. It was an altogether other matter whether a merciful God believed in this method. Was there any justification for such forgiveness in the blackened hearts of those prisoners?

Amid these musings I felt as if I were a machine not yet started up, the button not yet pushed that would influence my whole immediate future, as I believed my Sebald experience had done. I sensed that my companion felt the same way. We had both been to the Blue House several times before, yet we behaved as if we were in that world for the first time. The sense of momentary significance, perceived perhaps as nothing more than a feeling of melancholy that communicated itself from time to time in my companion’s otherwise placid demeanor was so powerful that when we finally left Frida Kahlo’s house, so reminiscent of the fallible artist, right down to its furnishings and vertical floral motifs, and passed the huge crowd of young women waiting to enter from the street, I felt compelled to say aloud, ”I feel as if we both played our roles pretty well in there. What Shakespeare play do you think best fits the day?” And Veronica Díaz laughed out loud and said, ”Maybe we’re the play. We’re on our way now to look at the house of a man who thought the whole world was a deluded drama.” We came to a channel that fed into the Churubusco River and saw the high wall that surrounded Leon Trotsky’s house, with its watchtower and the bullet holes still visible in one wall, a memento of an assassination attempt against Trotsky and his family carried out by the Stalinist painter David Alfaro Siqueiros and his fanatical group in May of 1940, the second of three such attempts on his life. Here we met another queue of tourists, occupied with perusing the Trotsky graffiti that stretched all the way down the block. We watched the scene for a while and as I recall I mused aloud for a moment about the third and final attack that happened a short time later in August of the same year, a fatal blow with an ice axe by Stalin’s agent, a Catalonian named Ramón Mercader who had been admitted to the house under cover of a Canadian passport and a false name. Then we walked down the street toward the city center and the metro station, and my companion said, ”It’s too bad we couldn’t get in. I could have showed you the office where my grandfather’s brother took something when he was left alone to guard the room while the dying philosopher was being taken to the hospital after the attack. He was working as a security guard at the house that summer. Later he gave the stolen item to my grandfather—a watchmaker—who still has it.”

These unexpected words set off a powerful, multi-layered fracture that would rend my understanding of all of recent history into its particular, essential parts. The crack had in many ways been there already in my encounter with the lions in their cages at the hacienda hotel. Now the feeling spread in a particular metaphysical direction of its own, an area of 20th-century history previously unknown to me entirely. The initial shift was partly accelerated by the small detail that I was from the eastern corner of northern continental Europe, from a small nation bordering Russia that spoke its own peculiar language. The same Stalin who murdered his former friend and ideological brother Trotsky just a stones throw behind us had also tried to take that little northern country by force during the second world war. Hearing my companion’s almost laconic words, I felt a curiosity altogether new take root within me.

2.

The next morning I began filming Casa Estudio, in the working-class neighborhood of Tacubaya about a kilometer from my hotel. I went inside the large, almost completely overgrown garden and many-terraced house built in the late 1940’s for a client and later renovated and eventually established as the home and workspace of the architect, Luis Barragán, who designed the exterior to blend seamlessly with the other buildings in the neighborhood. He wanted the house to be an organic part of the local culture, on a natural first-name basis with the prevailing working-class milieu, which it indeed achieved. The only thing that set the pale gray house with its wild garden, varied terraces and thousand-square meters of living space apart from the other buildings on the street was the length of its facade and the latticed window coverings of the second-floor library.

I had already spent two weeks of the previous year in the mysterious house hidden from the street by its scrim of facade, its rooms pervaded by white, yellow and pink, various degrees of deep silence and, in the words of the architect, a beauty that whispered like a wordless oracle. I entirely concurred with that description. The three-story building, made up of rooms of varying size where religious icons were on display, was of all things almost Islamic in atmosphere, in unrestrained ecumenical dialogue with Mexican indigenous tradition, to create not just a spiritual but also a visual whole. The same impression of devotion could be seen on the rooftop patio, heaven’s living room, which was evocative of the Muslim roof terrace tradition. The terrace had at one time opened out on a view of the garden, as all the central rooms of the house did, but after moving in the architect shut off the view with a wall in order to achieve the metaphysical impression of a fifth wall introduced by one of his role models, the Swiss architect Le Corbusier.

Six months earlier, filming at Le Corbusier’s testamentary work Le Cabanon, a cabin of two rooms and a foyer on the eastern ridge of Monaco Bay in the French Riviera, I had experienced the classic concept of home in a different form. Before he created this affecting, sixteen square-meter cabin, Le Corbusier had concentrated for decades on urban architecture and expansive, multi-story city planning and his idea of a house as a machine for living had become a worldwide principle, defining a human dwelling not as a living environment for the life of human emotions but rather as a purely technological object, like a car or a ship or an airplane. He had been opposed to the traditional irrational ambient design that squandered the promise of a new era and the Good Life achievable with the help of machines, and his architectural expressionism had begun to manifest itself in amoeba-like curves and unorthodox floor designs. In his paintings, Le Corbusier had already abandoned purism entirely. The cabin with its two-square-meter foyer had sprung up at a time of Le Corbusier’s life when he was working in Paris and longing for a change in his whole consciousness, and it represented a complete alteration in his understanding of the privileged westerner’s longing for square footage to make his life complete.

In contrast to Luis Barragán, who died peacefully in his sleep amid the glow of color and deep silence in 1988, Le Corbusier succumbed to a sudden heart attack in front of his cabin in August of 1965. The still horizon of the Mediterranean witnessed his fate, in a place he’d experienced as a paradise, where light, unfettered time, and harmony met. Le Corbusier had drawn the plans for the secluded cabin in 45 minutes as a gift for his wife, who grew up in the area, as they sat on the terrace of the adjoining restaurant in 1951, and the cabin was built four years later. Le Cabanon was 3.26 by 3.66 meters and 2.26 meters high, the proportions the architect had established for a human being with arms extended. The cabin’s ascetic look was emphasized by the spare interior of its single, plan-libre style room containing one wooden bed, a walnut veneer table attached to the wall, boxes for seating, a curtained-off porcelain toilet, which the architect considered the greatest invention of the modern age, a rudimentary washing nook, and a pitcher of water on a tree limb outside to use as a shower.

As I started filming shots of the volcanic stone steps that led into Casa Estudio’s entrance hall,

I thought of the varieties of human constructions of perfection. The everyday paradise created for the prisoners on an island in the Pacific meant a life sentence in a very different sense than these houses meant to the architects who designed them, places where they were conscious of the exoticness of their own privileged solitude. They understood that a modern person couldn’t achieve genuine solitude with a single mathematic—let alone architectonic—equation. It required living every aspect of one’s life in such circumstances. Once Le Corbusier, that godlike creator of multi-level communalism, had spent some time in his little cabin he realized the undeniable difference between the philosophical and the physical: it may be possible to control time and space at an intellectual level, as immutable elements in a building one has designed, and in the minds of the privileged clients it is designed for, but actually spending time there has a quite different effect on both the building and its inhabitant. Before designing Le Cabanon in the early 1950’s Le Corbusier had been in spiritual discussion with both Homer and Cervantes, which was manifested in his inclusion of the house in a drawing of Homer’s Iliad: he didn’t set the meeting of Zeus’s daughter Helena and the Trojan prince Paris in a palace. He set it in Le Cabanon. All that mythicness contained in one little wood-sided cabin that was humbleness itself, on a steep spit on the Côte d’Azur.

Now, looking at the work of Jalisco architect Luis Barragán, whose style was such a major influence on Le Corbusier at the start of his career— at the glowing rose-tinted entryway of Casa Estudio, its unrailed stone stairway dominated by Mathias Goeritz’s Mexican-tinged abstract altarpiece work of Luis—I pondered the emotionalism that was the wellspring of all of Barragán’s creativity and compared it to the asceticism of Le Corbusier’s final years. ”If a deep feeling of the presence of beauty is not created in the viewer, then the architect has made a great error,” Barragán believed.

My own emotion at Casa Barragán was speechlessness. I was very impressed by the atmosphere of the imposing house, its execution and the minimalism the house evokes in spite of its size, and that feeling grew stronger over the days I spent there. During a long shoot broken by meals at neighborhood restaurants and coffee breaks in the house’s office I captured footage of the building’s every essential detail, every element, all of its spaces and furnishings, the wild, overgrown garden that completed the resemblance to the Alhambra of Andalusia, and beyond the flagstoned entry the Patio de las Ollas with its pool and embracing canopy of greenery. As with all my subjects, whether in Japan, Russia, France or at home in Finland, I recorded everything with my small film camera using the prevailing natural light and the interior light created by the architect. Rose and yellow on a background of white dominated the space, the color absorbing the light and its reflections into itself like an architectonic laboratory in various parts of the house.

I had experienced a different kind of atmosphere, more stripped-down and modern, in architect Tadao Ando’s Koshino House, built in the late 1970’s and early 80’s as a country home for a Tokyo fashion designer near the Japanese town of Ashiya at the foot of Mt. Rokko. The 300-square-meter house was made up of two boxes and the curving extension that connected them, and was approached from above, which was itself puzzling. It made the viewer aware even from the outside of the house’s form, the adjoining rooms of the upper floor bringing to mind the monk’s chambers in Le Corbusier’s Sainte Marie de la Tourette. But the walls inside the house, where the spaces and natural light created a positive emptiness that felt like the house’s true furniture, were made of the same sturdy marble-like concrete as the outer walls, with rhythmic, moulded steel apertures developed by the architect, cast from hardwood moulds in a direct application of the wood building tradition used in Japanese temples. In his youth Tadao Ando had sincerely wanted to be a professional boxer, but he heard the call of creativity in the teachings of Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto and became a self-taught architect, shunning colleagues in his home country who were overly worshipful of formal education, and within the walls of Koshino House a visitor such as myself experienced the truth of the affirmation that he made a worldwide idea: the fact that hard concrete walls are in fact very soft and positively romantic to the touch.

At the start of my film project I had lain on my back on the cool floor of the living room at Ville Mairea, the house designed by Alvar Aalto in 1938 for his close friends Maire and Harry Gullichsen and their family, in the shade of a lush pine forest surrounding an old ironworks on the west coast of Finland near the Baltic Sea, the winter light slanting over my face through the south-facing windows, and I had known that the theme of my undertaking had left a permanent mark on me. As the dry January light awakened itself and the soft breeze that sifted snowflakes through the trees came through the broad window and felt its way over my face, I understood Sebald’s words and knew that I had to travel like an orphaned, migrating bird to different countries, to different continents, and rest in the patterns of sunlight formed in the rooms of different houses. And in those spaces I would remember that magical moment of light lingering on my face like a breath and settling something inside me on a dim winter day in a corner of Villa Mairea, and through it I would better understand the utterly privileged people who lived in all those cultures, granted the possibility of a home that preserved their deep humanity, a home designed with complete creative freedom, and also the people for whom the privilege of such a possession would always be lacking, like those in the poorer districts of Mexico City, living on the outskirts of the great metropolis amid wrecking yards and sheet-plastic shacks and cardboard neighborhoods, who had the audacity to dream of having a different kind of home.

The perfect beauty of Villa Mairea showed itself in its dazzling architectonic totality, but also in its numerous details, from the steel pillars and decorative columns in the ground floor library, covered in glossy black and white paint or wrapped in strips of rattan that beckoned you to touch them, to the artworks by Picasso, Braque, Calder and Léger, to the flower room reminiscent of Japan, the upstairs bedrooms and the children’s world of the nursery, the living room window that opened onto a view of the thatch-roofed smoke sauna at the back of the yard and the swimming pool against its backdrop of murmuring pine trees.

The goal of the family that commissioned the building was to create an ideal model of the home for a new age, an experiment in living in a classless society. But as the Gullischsens were moving into their new paradise, three months before the beginning of the second world war, their social utopia was soon to be crushed and the whole modern era to end in worldwide tragedy. As for Finland, it had known that on the other side of our 1300-kilometer eastern border was Josef Stalin, a man with a persecution complex and a compulsion to cross that border, attack and take control of our vigilant little country, its nightless summers and lightless winters, we who had successfully declared independence not long before amid the storms of Russia’s October revolution. He didn’t wish to make this ultimately unsuccessful maneuver merely to sate a lust for possession, but to provide protection against Adolf Hitler and all of the West, which he scorned just as he scorned God.

I had slept for hours at houses in various countries during filming and the experience had in every case been both meditative and therapeutic, as it was this time as well, on the ninth day of shooting, having completed the filming of all the other rooms of Barragán House—the small second-floor oratorio-room and library, the bedroom and afternoon room of the master of the house, the roof-terrace sky room, and the downstairs living room, its broad and tall cross-divided window connecting the room directly to the jungle-like garden, an untamed paradise in the daytime and a thoroughly tamed, unbroken sea of black at night, as the architect described it. For the cross-lattice of the window Barragán had used the paintings of his German-American friend, the artist Josef Albers as a model. When I awoke from these compulsory hour-long naps on the living room floor amid furniture designed by the architect and his Cuban-born interior designer Clara Porset, I didn’t know where I was for a moment because my sensation of the presence of light was the same as it had been while napping at Villa Mairea two years before. Perhaps the great war that blazed between the time of construction of these two houses had built a bridge connecting the the quality of light on either side of the Atlantic.

Every one of the five masters of residential architecture I’d chosen had an ambition to create the kind of architecture that they themselves would want to experience. And they had all achieved that—many of them with a great debt to Le Corbusier, who, like Medusa in the ancient myth, could turn a living thing to stone with a single glance and had, like some narcissistic early prophet, in many respects established the compositional range of the building arts of the 20th century. The exception to this circle of influence was the Russian Konstantin Melnikov, whose tower house of two cylinders erected on the long, narrow piece of land in central Moscow in 1928 and 29 was given the name Utopia before it was even completed.

The house, designed by a man who was a great admirer of Le Corbusier, withstood the thousands of airstrikes of World War Two and became a source of provocation to the new Stalinist socialist society. It stood like side-by-side satellites built for elitist space travel, and they wished it would disappear into the dark sky. Experiencing the house during my weeks of filming was almost like being sent in a time capsule to the world of a hundred years ago, reinforcing my belief in the timelessness of durable thematic elements, their ability to shift, to travel quite of their own volition through earthly time.

When I’d finished shooting in Konstantin Melnikov’s Utopia House, built for himself and his family about a half hour’s walk from the Kremlin, I had stayed in one of the oldest hotels in the city, on the banks of the Moscow River. I don’t know how many floors of the hotel had rooms in them in the 1920’s, but at the time I was there they were all on one level, along a single red-carpeted hallway, and the dim, garish room where I stayed for three weeks seemed at first glance so large that if someone had stood in the farthest corner near the window and spoken to me in a clear, normal voice, I wouldn’t have been able to make out what they were saying, regardless of what language they spoke. This auditorium-like room had a wall to wall carpet that gave off such a powerful smell that I was convinced there was still horse manure under it from the restless days of revolution when the place had been used as a makeshift stable.

I even remember musing aloud that Leon Trotsky himself, founder of the Red Army, coming on his famous armored train to Moscow from the east to inspect the troops, might have stayed in the room occasionally with his favorite stallion. So I felt considerable wonderment that late-October Tuesday—precisely one year before my shoot in Mexico City, where I would meet Veronica Díaz and she would make her unexpected comment about Leon Trotsky—when the kindly babushka at hotel reception told me that the leading figure of the Bolshevik revolution, later exiled from the Soviet Union, had indeed frequently visited the hotel in the 1920’s and even before, when the country soon to burst into political and physical flames of revolution still had its capitol in St. Petersburg.