1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: DigiCat

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In "Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends," the great Russian playwright and short story writer Anton Pavlovich Chekhov provides a vivid, intimate glimpse into his life through personal correspondence. This collection showcases Chekhov's keen observations, humor, and profound philosophical reflections, all articulated in his characteristic succinct prose. Each letter serves not only as a conduit of personal expression but also offers insight into the socio-political context of late 19th-century Russia, allowing readers to appreciate the personal nuances that influenced his celebrated works. Chekhov's style—marked by simplicity and emotional depth—renders these letters as poignant as his fictional narratives, blending literary artistry with genuine human experiences. Chekhov, born in 1860 to a modest family, immersed himself in the world of literature and medicine, which closely informed his writing and personal ethos. Although he achieved prominence as a playwright, these letters reveal the man behind the public persona: a devoted brother, a comrade in artistic endeavors, and a contemplative spirit grappling with the challenges of his era. His correspondence reflects not just personal thoughts, but the broader cultural and social dynamics of his time. "Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends" is highly recommended for readers seeking a more profound understanding of Chekhov's character and inspirations. This collection is an indispensable read for students of literature and lovers of humanistic narrative, revealing the delicate interplay between the writer's life and his timeless literary creations. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection gathers a wide-ranging selection of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov’s private correspondence, presented under the title Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends. It offers a continuous view of his life as a writer and physician, from early success to mature authority, by means of letters addressed to relatives, collaborators, editors, and fellow artists. A preliminary biographical sketch situates the letters within their historical and personal contexts, enabling readers to follow the evolution of Chekhov’s concerns and methods. Rather than anthologizing finished fictions or plays, this volume preserves the documentary record that runs alongside their conception, rehearsal, publication, and reception.

The texts represented are predominantly letters, supplemented by occasional telegrams and travel notes embedded in the correspondence. The senders and recipients named here—brothers, sister, mother, editors, mentors, and colleagues—define a network that sustained Chekhov’s daily work. Among the correspondents are A. S. Suvorin, N. A. Leikin, D. V. Grigorovitch, V. G. Korolenko, A. F. Koni, A. N. Pleshtcheyev, and later theatre figures such as K. S. Stanislavsky and V. I. Nemirovitch-Dantchenko, as well as M. O. Menshikov, Gorky, and O. L. Knipper. Dated headings and place markers—Moscow, Sumy, Tomsk, Irkutsk, Yalta, Badenweiler—anchor each document in lived time and space.

Taken together, these letters reveal the unifying themes that also mark Chekhov’s fiction and drama: attentiveness to ordinary life, ethical self-scrutiny, and an economy of expression that trusts implication over declaration. The correspondence is rich in humor and irony, yet guided by compassion. We see a stylistic hallmark of clarity and restraint that leaves room for the interlocutor and the reader. The letters’ informal occasions—requests, plans, thanks, advice—become occasions for a precise, humane voice that resists slogans and certainties. This voice provides a running commentary on the pressures of craft, the demands of friendship, and the responsibilities of work.

The early letters trace Chekhov’s transition from a hardworking contributor to periodicals into a widely published author. Exchanges with editors such as N. A. Leikin and A. S. Suvorin record negotiations about deadlines, formats, and the practicalities of print culture in late-nineteenth-century Russia. Letters to his brothers and sister show the family’s interdependence and the steadying presence of home. Throughout, the doubleness of his vocation is evident: medical commitments overlap with literary ones, and the tone moves easily from playful to practical. The same discipline that shaped his early comic pieces undergirds his mature approach to subject and form.

A distinguished segment concerns the 1890 journey across Siberia to Sakhalin, documented here by letters from Tomsk, Irkutsk, Station Listvenitchnaya, and other waypoints, including Pokrovskaya Stanitsa. The correspondence chronicles distances, encounters, and the purposefulness of a long investigative trip. These letters foreshadow the research that would culminate in his nonfiction study of the island and its penal colony. The voice remains measured, observational, and exact, preferring concrete details to general polemic. The resulting portrait is one of travel as inquiry, with friendship and editorial counsel sustaining the effort from afar.

The Melikhovo years, represented by numerous letters dated from that estate, display Chekhov at full stretch: writing, practicing medicine, and taking part in local civic life. Family letters bring readers into the work of maintaining a household and property; professional letters articulate the standards he set for prose and the stage. His exchanges with A. F. Koni and others reveal respect for law, responsibility, and public discourse. The balance of personal and professional energies is recorded without sentimentality. The voice stays even, precise, and hospitable to differing opinions, while insisting on the primacy of honest observation over programmatic messaging.

Later letters from Yalta and other southern locales show a new geography for an ongoing discipline. The correspondence with the Moscow Art Theatre’s leaders and actors—K. S. Stanislavsky, V. I. Nemirovitch-Dantchenko, and O. L. Knipper—traces rehearsals, casting, and the evolving language of performance. Letters to Gorky register collegial encouragement and thoughtful critique within a rapidly changing literary landscape. The coastal setting appears as a working environment rather than retreat: a place from which Chekhov coordinated premieres, proofs, and benefactions, and kept in touch with family in Moscow and beyond.

Family correspondence is central to this volume. Letters to his mother, sister, and brothers reveal practical solicitude—advice about money, health, and travel—alongside moral tact and humor. They preserve the cadences of daily life, bearing news of apartments, gardens, weather, and guests, and they chart the rhythms of absence and reunion. The self-portrait that emerges is unforced: industrious, affectionate, sparing of complaint, skeptical of grand pronouncements, alert to the feelings of others. The same patient attention he gave to characters on the page is given here to real people, in language that remains measured even under pressure.

A sustained thread of editorial and journalistic relationships runs throughout. The correspondence with Suvorin and Leikin records the mechanics of pitches, proofs, and payments; with F. D. Batyushkov and M. O. Menshikov it touches on criticism, taste, and the periodical press. Chekhov is wary of polemics that foreclose conversation, yet exacting about standards and factual accuracy. These letters sketch a working map of Russian literary institutions—newspapers, journals, publishing houses—and the negotiations that enabled his stories and plays to reach readers and audiences across the empire and abroad.

Stylistically, the letters distill Chekhov’s aesthetic. The sentences are clean, the humor dry, the images carefully chosen, the emotion controlled by form. He allows subtext to accumulate through juxtaposition rather than proclamation. The idiom ranges from colloquial to formally courteous, depending on addressee and situation, but the underlying values are consistent: honesty, proportion, and sympathy. While never intended as essays on craft, the letters repeatedly return to questions of construction, tone, and the ethics of representation, articulating an art that prefers suggestion to explanation and trusts readers to complete the meaning.

For scholars, students, and general readers alike, the correspondence illuminates the making of a major modern artist without reducing the work to biography. It clarifies contexts—the economics of publishing, the growth of a new theatrical institution, and the social milieu of physicians, critics, and writers—while respecting the autonomy of the fiction and plays. The letters also witness artistic friendships that shaped Russian and European culture at the turn of the century. They refine our understanding of influence, collaboration, and reception, showing how literary life depended on patient, courteous communication across distance.

This edition presents the letters in a broadly chronological order, retaining place and date lines that guide the reader through Chekhov’s movements from Moscow to provincial towns, across Siberia, and south to the Crimea, and finally to Badenweiler. The sequence is selective rather than exhaustive but aims for representative fullness, setting personal notes alongside professional negotiations. The biographical sketch at the outset frames the documents without preempting them. Read consecutively, the letters form a narrative of work and care; read selectively, they yield precise glimpses of decisive moments in a life devoted to clarity, modesty, and service.

Author Biography

Introduction

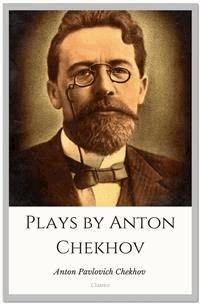

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (1860–1904) stands among the central architects of modern short fiction and drama, a physician whose clinical clarity deepened his literary art. The collection at hand—anchored by a Biographical Sketch and an extensive body of Letters—traces his movement from Taganrog to Moscow, Melikhovo, Yalta, and finally Badenweiler. Across addresses to family, editors, actors, and fellow writers—N. A. Leikin, A. S. Suvorin, D. V. Grigorovich, V. G. Korolenko, A. F. Koni, K. S. Stanislavsky, V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, M. Gorky, and O. L. Knipper—the correspondence reveals the working day of a doctor-writer, his evolving aesthetics, and the social conscience that underpins his prose and plays.

Chekhov’s signature works—short stories such as The Steppe, Ward No. 6, The Black Monk, The Lady with the Dog, and In the Ravine, and plays including The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters, and The Cherry Orchard—are illuminated by the Letters’ workshop-like candor. Nonfiction exertion culminates in The Island of Sakhalin, a study seeded in the Siberian and Far Eastern letters dated 1890. Throughout, the collection registers rehearsals, editorial negotiations, family obligations, and the pressures of illness. The Letters function not as mere documentary addenda but as a parallel narrative of composition, reception, and artistic self-scrutiny across the late imperial Russian literary world.

Education and Literary Influences

Chekhov was educated at the Taganrog Gymnasium before moving to Moscow in 1879 to study medicine at Moscow University. Financial strain drew him into print while still a student; under the playful pseudonym “Antosha Chekhonte,” he supplied sketches to N. A. Leikin’s Oskolki. The Letters to Leikin in this collection register the exacting pace of feuilleton journalism—deadlines, fees, and editorial temperaments—as Chekhov refined his compressed narrative method. Medical training left a lasting imprint: empirical observation, a distrust of grand diagnoses, and a commitment to economy. The Biographical Sketch and early metropolitan letters show a writer learning to balance clinic hours with an expanding professional identity.

Intellectually, Chekhov drew from the Russian realist tradition—Gogol’s tonal juxtapositions, Turgenev’s lyric restraint, and Tolstoy’s moral testing—while absorbing the concision of the French short story, notably Maupassant. The Letters disclose how mentors and interlocutors shaped his course: D. V. Grigorovich’s encouragement, A. N. Pleshcheyev’s counsel, and A. S. Suvorin’s editorial access. Later, the theatre sharpened his sense of subtext; exchanges with K. S. Stanislavsky and V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko reveal an evolving dramaturgy attentive to ensemble acting and understatement. Reading and travel—glimpsed even in playful salutations like “My Dear Tunguses!”—broadened his anthropological eye, culminating in the Sakhalin investigation’s humane method.

Literary Career

Chekhov’s early career unfolded in the quick-turn world of humorous weeklies and city papers. The Letters to Leikin and Suvorin capture a writer negotiating column inches and tone while edging from comic vignettes toward denser, morally shaded prose. By the late 1880s, the shift is unmistakable: The Steppe announced a broadened canvas anchored in landscape and memory. Correspondence from Moscow and Sumy (1888–1889) in this collection tracks revisions, doubts, and responses from peers like A. N. Pleshcheyev and D. V. Grigorovich, illuminating the passage from anecdote to psychological scene, from punchline to resonance.

In 1890 Chekhov undertook the arduous journey to Siberia and Sakhalin Island. The sequence of Letters—From the Steamer, Tomsk, Irkutsk, Station Listvenitchnaya, Pokrovskaya Stanitsa—forms a travelogue of observation: prisons, ferries, taiga roads, weather, budgets, and the human ledger he would later systematize. Telegrams to his mother and dispatches to his sister run parallel to reports to A. S. Suvorin, joining filial concern to civic inquiry. The Island of Sakhalin, serialized a few years later, grew directly from these notes, adopting a statistical and testimonial method that distinguished it within Russian nonfiction, without abandoning the compassion evident in the Letters.

The Melikhovo years (early 1890s) were a summit of productivity. Letters from Melikhovo in 1892 and after show a writer immersed in local life—medical rounds, schooling, and agrarian crises—while composing major stories such as Ward No. 6, The Black Monk, and, soon after, Rothschild’s Fiddle. His exchanges with A. F. Koni probe legal and ethical questions reflected in the fiction’s institutions and dilemmas. Correspondence with the Lintvaryov family (N. M. Lintvaryov, Elena Mikhailovna) records health work and rural culture. Editorial topics recur in letters to Suvorin, but the stories move toward interiority, silence, and moral ambiguity that would define his mature voice.

Chekhov’s dramatic career, reflected in letters to Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko, consolidates the late 1890s. After The Seagull’s first failure and later triumph, he refined a theatre of pauses, ensemble, and subtext. Letters in this collection show him addressing tempo, gesture, and the dignity of everyday speech. Uncle Vanya (reworking The Wood Demon), Three Sisters, and The Cherry Orchard advance his dramaturgy of thwarted desires and social change. Exchanges with O. L. Knipper—an actor central to these productions and later his wife—interweave practical stage matters, touring schedules, and composition, exposing the hinge between private life and public art without diminishing his insistence on artistic autonomy.

From 1899 onward, Yalta correspondence maps a quieter but no less intense period: medical treatments, guests, proofs, and the making of late stories like The Lady with the Dog and In the Ravine. Letters to Gorky register mutual esteem and debate; to Suvorin, a cooling over public questions, even as logistics of publication persisted. Communications with G. I. Rossolimo and other physicians reflect self-care and consultation, while notes to his sister Masha steer family finances and property. The Letters to S. P. Dyagilev and to theatre colleagues broaden the cultural radius, confirming Chekhov’s position at the crossroads of Russia’s literary, journalistic, and stage communities.

Beliefs and Advocacy

A physician by training and conviction, Chekhov approached social duty pragmatically. Melikhovo letters from 1892 describe organizing cholera measures, distributing medicines, and funding local schools and libraries. Communications to local officials and acquaintances—E. P. Yegorov, A. I. Smagin—detail supplies, road repairs, and communal needs, showing a preference for concrete tasks over manifesto. This administrative energy coexisted with gentle irony in private letters and a reluctance to grandstand publicly. The Letters thus reveal how his humanitarianism—equally present in village clinics, correspondence, and fieldwork—fed the understated ethics of his stories and the compassionate neutrality he strove for in narrative perspective.

Chekhov guarded artistic independence. Letters to Suvorin chronicle decades of cooperation and principled disagreement about the press and public life; to Korolenko and Koni, they engage justice, responsibility, and the human cost of institutions. The Sakhalin cycle documents penal reform concerns and methodological rigor—counting households, interviewing convicts, examining officials—without polemic. Theatre letters defend subtle acting and resist didactic staging, aligning with his broader distrust of slogans. Family letters—such as admonitions to his brothers and guidance to his sister—advocate sobriety, work discipline, and kindness. Across correspondents, the Letters show a consistent ethic: skepticism of grand theories, fidelity to fact, and care for persons.

Final Years & Legacy

By the early 1900s, Chekhov’s tuberculosis required extended stays in Yalta and periodic treatment abroad. He married O. L. Knipper in 1901, and their affectionate, work-focused correspondence—preserved here alongside letters to Stanislavsky, Nemirovich-Danchenko, and Gorky—bridges domestic life and theatrical labor. The collection’s final sequence, sent from Berlin and Badenweiler in June 1904, precedes his death there soon after. His legacy is twofold: he revolutionized the short story’s architecture—open endings, implied causality, moral tact—and recast drama as ensemble-driven, subtext-rich dialogue. The Letters, spanning Moscow to Tomsk, Irkutsk, Yalta, and Badenweiler, remain an indispensable companion to the plays, stories, and Sakhalin study.

Historical Context

This collection follows Anton Chekhov’s life and work across the volatile decades of late imperial Russia, from the 1880s through 1904. The letters span the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II, years marked by political reaction after the 1881 assassination of Alexander II, accelerating industrialization, and growing strain between the state and the intelligentsia. Chekhov’s voice moves from a young medical student and humorist supporting his family to an internationally admired writer and dramatist, repeatedly drawn into questions of social welfare, censorship, and artistic responsibility. Read together, the letters map the cultural topography that shaped Russian literary life and public debate on the eve of the twentieth century.

Chekhov’s earliest letters emerge from family hardship after his father’s bankruptcy in Taganrog and the family’s move to Moscow. While studying medicine at Moscow University (1879–1884), he wrote comic sketches for the bustling weekly press, notably for N. A. Leikin’s Oskolki. These years unfolded under tightened press controls and university restrictions characteristic of the Alexander III era, shaping his cautious, ironic tone. The correspondence to siblings and cousins records the price of urbanization and new mass readerships: relentless deadlines, small payments, and the grind of freelance life. Yet it also reveals a nascent social physician, attentive to poverty, housing, and everyday practicalities.

As his reputation grew, Chekhov navigated Russia’s powerful periodical marketplace. The letters to editors—Leikin, later A. S. Suvorin of Novoye Vremya—illuminate the economics and politics of print: contractual expectations, editorial line, audience taste, and the latitude (or lack thereof) for artistic experimentation under censorship statutes from the early 1880s. He balanced the quick turnover of feuilletons with increasingly crafted stories, testing how far satire and observed detail could reach within commercial constraints. The correspondence documents a writer learning to husband his time, guard his rights, and define a distinctive voice without severing ties to the mass readership that first sustained him.

Exchanges with senior writers such as D. V. Grigorovich and A. N. Pleshcheyev locate Chekhov within a culture of mentorship that linked generations of the Russian literary world. Grigorovich’s 1886 praise encouraged him to treat literature as a serious vocation, soon reinforced by institutional recognition when the Russian Academy awarded Chekhov the Pushkin Prize in 1888 for a story collection. Letters of this period touch on The Steppe and other works that consolidated his reputation. Contacts with V. G. Korolenko and other public intellectuals connected him to liberal currents concerned with legal reform, peasant welfare, and the responsibilities of the intelligentsia.

Late-1880s letters carry the texture of provincial Russia—Taganrog, Sumy, and small towns—where estate cultures, zemstvo institutions, and rail links intersected. They also register personal losses, most notably the 1889 death from tuberculosis of his artist brother Nikolay, which deepened Chekhov’s engagement with illness and responsibility. Exchanges with family and with editors highlight a turning point: the shift from short comic pieces toward psychologically exacting prose and, soon, the theatre. Against a backdrop of tightening social discipline under Alexander III, Chekhov’s attention to bureaucratic absurdity and moral ambiguity sharpened, yielding the understated ethical register that characterizes his mature style.

The 1890 journey to Sakhalin Island, recorded here in letters from steamers and Siberian towns—Tomsk, Irkutsk, and the Baikal region—placed Chekhov within contemporary debates on the penal system and exile. Sakhalin functioned as a remote penal colony and site of forced settlement; Chekhov traveled thousands of kilometres to conduct a population census and gather data firsthand. His impressions, later distilled into The Island of Sakhalin, exposed brutalities, administrative inertia, and public health deficiencies. The correspondence conveys the logistical hardships of pre-rail Siberia and Chekhov’s belief that accurate observation—and statistics—were necessary for humane reform.

These letters intersect with the era’s technologies of mobility. The Trans-Siberian Railway was inaugurated in 1891, after Chekhov’s arduous overland-and-river journey, and would transform Siberian traffic, settlement, and state capacity. His dispatches, including the joking “My dear Tunguses!”, reflect encounters with diverse populations and the mixed impact of colonization, exile, and trade on indigenous peoples and settlers. Together they mark a transitional moment: empire stretched by infrastructure projects, yet still reliant on steamers, horse transport, and telegraph lines. Chekhov’s travel writing joins a broader imperial literature of observation, while resisting sensationalism through a clinical, documentary tone.

The early 1890s brought severe strain inside European Russia. Crop failures led to the 1891–1892 famine; cholera and typhus threatened rural districts. After purchasing Melikhovo in 1892, Chekhov served as a zemstvo doctor, organizing relief, treating peasants, and advocating sanitary measures. Letters from Melikhovo document local governance under the zemstvo system, the practicalities of medical service, and grassroots philanthropy. He helped build and equip rural schools and a modest clinic, collected funds, and mediated between officials and villagers. This civic dimension—less visible in his fiction—appears vividly in the correspondence, aligning him with a medical intelligentsia committed to public health and education.

Chekhov’s letters from Vienna, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Naples, Monte Carlo, and Paris (mainly 1891–1894) fit the long-standing European itinerary of Russia’s educated class. These travels were restorative—after the Sakhalin ordeal—and formative for theatrical and artistic sensibilities. The correspondence registers museums, opera, and the contrasting pace of Western urban life. While he avoided manifestos, his observations participate in a wider Russian conversation on Europe as a mirror and foil: technical efficiency, municipal hygiene, and civic culture versus the sprawl and improvisation of Russian provincial life. They also reveal the cosmopolitan networks through which Russian writers circulated.

The theatre became Chekhov’s second public arena. Letters around and after the 1896 failure of The Seagull in St. Petersburg trace a crisis of artistic identity and the practical realities of the Imperial stage—star systems, censorship, and rehearsal conventions. The founding of the Moscow Art Theatre in 1898 by K. S. Stanislavsky and V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, and its ensemble ethos and psychological realism, furnished a congenial home for Chekhov’s dramaturgy. Correspondence with both men shows negotiation over casting, pacing, subtext, and staging, embedding his plays within a broader European shift toward modern acting methods and naturalistic production.

Chekhov’s association with A. S. Suvorin, powerful publisher of Novoye Vremya, illuminates the politics of the press. Their long, candid correspondence charts editorial influence and personal support, but also a growing ideological rift. The Dreyfus Affair in France (1894–1906) reverberated across Russia’s public sphere; Chekhov defended Dreyfus and decried antisemitism, while Suvorin espoused a harder conservative line. The letters capture this divergence and its consequences for literary alliances. They show how international scandals could reshape Russian networks, widening the split between liberal and reactionary camps in the fin-de-siècle intelligentsia.

By 1897 Chekhov’s pulmonary illness forced periodic retreats and, in 1899, a move to Yalta, a Black Sea resort benefiting from a mild climate and modern sanatoria. Letters from Crimea describe the rhythms of convalescence, the arrival of friends, and continuing work for the stage. They also intersect with rising social tensions under Nicholas II: labor unrest, student demonstrations, and sharper surveillance of the press and theatre. Exchanges with jurist A. F. Koni and physician G. I. Rossolimo link medicine, law, and literary culture, while letters to Maxim Gorky register sympathy for social critique alongside a preference for reformist rather than incendiary rhetoric.

Correspondence with women central to Chekhov’s circle—Lika Mizinova, Madame M. V. Kiselyova, Lydia Avilov, and actress Olga Knipper—documents the changing role of educated women in Russia’s literary and theatrical life. Their letters traverse salon networks, editorial projects, charity work, and rehearsal rooms. Chekhov’s marriage to Knipper in 1901 connected him even more closely to the Moscow Art Theatre during its most innovative period. The epistolary distance between Yalta and Moscow reveals the logistical modernity of the age—rail, telegraph, and express post—and the human strains of continuous production schedules, censorship approvals, and touring in a rapidly professionalizing theatre world.

Several letters situate Chekhov among jurists, editors, and activists who treated law as a lever of modernization. His work on Sakhalin, with its statistical census and analysis of penal practice, aligns with a late nineteenth-century faith in empirical inquiry as a prelude to reform. Exchanges with Koni and with editors of serious journals show a preference for careful investigation over polemic. The correspondence also traces the formation of civil society practices—fundraising, voluntary associations, and zemstvo initiatives—through which educated Russians sought to address schooling, medical infrastructure, and disaster relief within the constraints of autocratic administration.

Technological change threads through the collection. Railways, steam navigation, and telegraphy governed the tempo of Chekhov’s travel and correspondence, from Siberian riverboats to rapid Moscow–Yalta exchanges. Improvements in postal reliability and newspaper distribution created a national literary market, while also intensifying censorship’s reach. The letters mention proofs, deadlines, and the materiality of print—galleys, photographs, and translations—underscoring how industrial modernity reshaped authorship into a logistical enterprise. This infrastructure aided philanthropic coordination during epidemics and famines and enabled the Moscow Art Theatre’s touring model, thereby binding together literature, medicine, and performance in a shared communicative environment.

The early 1900s letters engage explicitly with public controversies. In 1902 the government annulled Maxim Gorky’s election to the Russian Academy of Sciences; Chekhov and V. G. Korolenko resigned their Academy memberships in protest—a principled act recorded in their correspondence. Letters to S. P. Diaghilev signal contact with a younger generation promoting Mir iskusstva’s aesthetics and, later, modernist theatre and ballet. Exchanges with critics like F. D. Batyushkov and with K. S. Stanislavsky and V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko document debates over artistic authority, ensemble discipline, and the place of social questions on the stage amid growing political agitation.

The collection closes with dispatches from Berlin and Badenweiler (June 1904), where Chekhov sought treatment in a German spa town known for respiratory care. These last letters, written shortly before his death in July 1904, are matter-of-fact, concerned with health, manuscripts, and friends. They also mark the end of an era: within a year Russia would enter the 1905 Revolution following military disasters and domestic unrest. Chekhov’s life ended before those upheavals, yet the correspondence anticipates them in its attention to administrative paralysis, civic initiative, and the increasingly public role of writers and theatres in social life. Their resonance outlived him decisively—politically, aesthetically, and humanely.

Synopsis (Selection)

Biographical Sketch

A concise portrait of Chekhov’s life sets the stage for the correspondence, framing his dual identity as physician and writer alongside the pressures of family responsibility. It sketches the social and cultural contexts that shaped his temperament, humor, and discipline, illuminating how travel, illness, and literary ambition intersected throughout his life.

Letters: General Overview

Spanning family notes, professional exchanges, and travel dispatches, these letters trace Chekhov’s movement through cities and seasons of work. They reveal his laconic wit, practical ethics, and sensitivity to everyday detail, while charting a steady deepening of artistic conscience and social concern.

Early Family Correspondence (Brothers, Sister, Mother, Uncle, Cousin; incl. telegrams)

Letters to his brothers Mihail, Nikolay, Alexandr, and Ivan; to his sister; mother; uncle M. G. Chekhov; and cousin Mihail show a candid, often playful voice balancing warmth with admonition. He writes of money, health, work, and duty, mixing affectionate nicknames and brief telegrams with sober advice, revealing the emotional economy of a large, interdependent family.

Moscow and Sumy Letters, 1888–1889 (datelines and short notes)

Marked by place-and-date headings like Moscow and Sumy with specific days in late 1888 and 1889, these notes track Chekhov’s routine pressures and production tempo. The tone is brisk and observant, revealing the city’s pull, small crises of time and health, and the practical planning behind his output.

Letters to N. A. Leikin

Chekhov’s exchanges with Leikin center on work rhythms, expectations, and the latitude he seeks for experimentation. The tone moves between collegial and gently ironic, as he weighs audience taste against his own evolving standards.

Letters to A. S. Suvorin

Across many years, Chekhov’s letters to Suvorin form an intellectual through-line, debating craft, taste, and public life alongside personal health and travel. The voice is frank, analytical, and dryly humorous, showing how artistic principle and practical necessity are negotiated over time.

Letters to D. V. Grigorovitch and V. G. Korolenko

These exchanges with established peers revolve around encouragement, standards of realism, and conscience in literature. Chekhov’s tone is respectful yet independent, signaling his wish to learn without imitation, and to match ethical seriousness with formal economy.

Letters to A. N. Pleshtcheyev and I. L. Shtcheglov

Chekhov discusses stories-in-progress, reading habits, and the tenor of contemporary criticism with a pragmatic, lightly self-mocking candor. He probes how brevity can carry moral weight, and how to resist bombast without losing gravity.

The Siberia and Far East Journey, 1890 (From the Steamer; Tomsk; Irkutsk; Station Listvenitchnaya; Pokrovskaya Stanitsa; “My dear Tunguses!”; telegrams)

Dispatches sent from steamer decks, waystations, and remote towns register the physical strains of travel and close observation of provincial and frontier life. Chekhov’s tone mixes curiosity and compassion with logistical grit, and quick postcards to family punctuate the record with urgency and care.

European Tour Letters: Vienna to Paris (incl. “My dear Czechs”)

From Vienna, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Naples, Monte Carlo, and Paris, Chekhov records art, street life, and the contrast between spectacle and fatigue. The travel voice is witty, clear-eyed, and intermittently celebratory, balancing aesthetic impressions with reminders of health and discipline.

Country Retreats: Alexin and Bogimovo

Notes from Alexin and Bogimovo show Chekhov recalibrating in the countryside, weighing rest against steady work. The letters carry a lighter air—photographs, jokes, and observational miniatures—yet still circle back to the mechanics of writing and correspondence.

Letters to L. S. Mizinov (Lika)

Playful, intimate, and occasionally teasing, these letters to L. S. Mizinov blend confidential asides with snapshots of daily routine and travel. Beneath the lightness lies a careful emotional tact, as Chekhov measures closeness with a protective restraint.

Letters to Madame M. V. Kiselyov and A. S. Kiselyov

Chekhov’s messages to the Kiselyov circle are sociable and attentive, often situating personal news within a wider map of movement and work. They exemplify his polite urbanity, using small particulars to sustain friendship at a distance.

Letters to the Lintvaryov Family (N. M. Lintvaryov; Madame Lintvaryov)

Correspondence with the Lintvaryovs is rooted in hospitality and the rhythms of provincial life, with attention to weather, guests, and health. Chekhov writes with grateful precision, using small social scenes to reflect on rest, reading, and productivity.

Melikhovo Period Letters

Dated from Melikhovo with returns to Moscow, these letters interleave estate tasks, medical duties, and literary planning. The tone is industrious, humane, and quietly reformist, revealing how rural observation sharpened his sense of social texture and narrative restraint.

Professional and Literary Correspondence beyond the circle (A. F. Koni; A. I. Ertel; F. D. Batyushkov; E. P. Yegorov; A. I. Smagin; V. A. Tikhonov; P. I. Kurkin; V. M. Sobolevsky; I. I. Orlov; M. O. Menshikov; V. A. Posse; E. M. S.)

These letters range from cordial professional exchanges to thoughtful critiques, touching on publishing logistics, reception, and ethical questions in prose. Chekhov preserves clarity and courtesy even in disagreement, favoring concise argument over manifesto while anchoring opinions in concrete examples.

Letters to Madame Avilov (Lidya Alexeyevna)

Candid and steady in tone, these letters balance personal support with practical talk of reading, drafts, and health. Chekhov’s voice is considerate and measured, using gentle humor to lighten earnest counsel.

The Moscow Art Theatre Circle (K. S. Stanislavsky; Madame Stanislavsky; V. I. Nemirovitch-Dantchenko; A. L. Vishnevsky)

Focused on rehearsal realities, casting, and staging, these exchanges trace Chekhov’s evolving relationship to performance and audience. He weighs nuance over declamation, pressing for lifelike tempo and restraint while adopting a collegial, problem-solving tone.

Letters to O. L. Knipper

These notes to the actress are intimate, witty, and alert to the pressures of rehearsal, touring, and separation. Chekhov favors quick, vivid images and reassuring brevity, revealing care without sentimentality.

Letters to Gorky

Spanning admiration, debate, and mutual encouragement, the Gorky correspondence probes literary responsibility and the social reach of art. Chekhov’s tone is both comradely and exacting, championing clarity and compassion over rhetoric.

Letters to G. I. Rossolimo

Exchanges with Rossolimo, grounded in medicine and observation, reveal Chekhov’s clinical poise and empirical curiosity. He treats facts with narrative tact, aligning scientific interest with ethical reserve.

Letters to S. P. Dyagilev

Brief and businesslike, these late letters manage practical matters with crisp politeness. They distill Chekhov’s mature style of correspondence—efficient communication softened by a courteous aftertone.

Letters to Father Sergey Shtchukin

Chekhov writes to a clergyman with respect and clear moral focus, reflecting on conscience, consolation, and daily burdens. The tone is restrained and sincere, foregrounding shared human concerns over doctrinal debate.

Yalta Letters and Late Years

Centered in Yalta and later spa towns, these letters balance convalescence with ongoing literary and theatrical commitments. Chekhov’s voice grows sparer yet remains attentive to others, converting fatigue into precision and humor into a form of care.

Final Letters: Berlin and Badenweiler; concluding notes

The last dated messages from Berlin and Badenweiler are composed, unhurried, and focused on essentials—health, loved ones, and work left in motion. They read as humane closures, consistent with a lifelong preference for understatement over grand farewell.

Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

Of the eighteen hundred and ninety letters published by Chekhov’s family I have chosen for translation these letters and passages from letters which best to illustrate Chekhov’s life, character and opinions. The brief memoir is abridged and adapted from the biographical sketch by his brother Mihail. Chekhov’s letters to his wife after his marriage have not as yet been published.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

In 1841 a serf belonging to a Russian nobleman purchased his freedom and the freedom of his family for 3,500 roubles, being at the rate of 700 roubles a soul, with one daughter, Alexandra, thrown in for nothing. The grandson of this serf was Anton Chekhov, the author; the son of the nobleman was Tchertkov, the Tolstoyan and friend of Tolstoy.

There is in this nothing striking to a Russian, but to the English student it is sufficiently significant for several reasons. It illustrates how recent a growth was the educated middle-class in pre-revolutionary Russia, and it shows, what is perhaps more significant, the homogeneity of the Russian people, and their capacity for completely changing their whole way of life.

Chekhov’s father started life as a slave, but the son of this slave was even more sensitive to the Arts, more innately civilized and in love with the things of the mind than the son of the slaveowner. Chekhov’s father, Pavel Yegorovitch, had a passion for music and singing; while he was still a serf boy he learned to read music at sight and to play the violin. A few years after his freedom had been purchased he settled at Taganrog, a town on the Sea of Azov, where he afterwards opened a “Colonial Stores.”

This business did well until the construction of the railway to Vladikavkaz, which greatly diminished the importance of Taganrog as a port and a trading centre. But Pavel Yegorovitch was always inclined to neglect his business. He took an active part in all the affairs of the town, devoted himself to church singing, conducted the choir, played on the violin, and painted ikons.

In 1854 he married Yevgenia Yakovlevna Morozov, the daughter of a cloth merchant of fairly good education who had settled down at Taganrog after a life spent in travelling about Russia in the course of his business.

There were six children, five of whom were boys, Anton being the third son. The family was an ordinary patriarchal household of the kind common at that time. The father was severe, and in exceptional cases even went so far as to chastise his children, but they all lived on warm and affectionate terms. Everyone got up early, the boys went to the high school, and when they returned learned their lessons. All of them had their hobbies. The eldest, Alexandr, would construct an electric battery, Nikolay used to draw, Ivan to bind books, while Anton was always writing stories. In the evening, when their father came home from the shop, there was choral singing or a duet.

Pavel Yegorovitch trained his children into a regular choir, taught them to sing music at sight, and play on the violin, while at one time they had a music teacher for the piano too. There was also a French governess who came to teach the children languages. Every Saturday the whole family went to the evening service, and on their return sang hymns and burned incense. On Sunday morning they went to early mass, after which they all sang hymns in chorus at home. Anton had to learn the whole church service by heart and sing it over with his brothers.

The chief characteristic distinguishing the Chekhov family from their neighbours was their habit of singing and having religious services at home.