9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

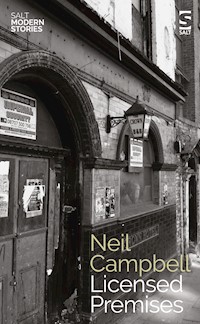

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'Nobody believes what they see on TV, so they want to look for something else, an alternate reality, or a conspiracy theory, and it's interesting to explore it, Twitter is fucking full of it, especially now. It's no wonder people round here are into it, but you don't have to read all that shit, just have some mushrooms and wander round Lidl off your tits.' In these fourteen northern tales, Campbell takes us from the edgelands of Manchester to the cloistered villages of The Peak District, Northumberland and Scotland, and illuminates the lives of outsiders, misfits, loners and malcontents with an eye for the darkly comic. A wild-eyed man disturbs the banter in a genial bookshop. A fraught woman seeks to flee a collapsing reservoir. A failed academic finds solace in a crime writer's favourite pub. A transit van killer stalks a railway footpath. A poet accused of plagiarism finds his life falling apart.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

iii

NEIL CAMPBELL

LICENSED PREMISES

v

for Mum

Contents

Jackdaws

Agiant black crucifix was chained to one of the rocks, and there was a laminated sheet of paper stapled to the wood with black type on it and a photograph of the girl.

One morning I walked out into a blizzard and the snow on the doorstep reached my kneecaps. The gritters from the council didn’t come until the day before the snow melted, meaning all the cars on the lane had to be parked outside the pub for almost a month. The jackdaws stood out against the snow-covered hillsides, and the drystone walls cut the sloping fields into segments.

When the sun finally came out after a month the white-clothed trees around the cricket ground sparkled. Blackbirds and song thrushes spilled white dust from the branches and silver drops fell off the leaves. The Churn was an alpine peak rolling over to a similarly submerged Far Head. The Pike shimmered in a covering of carbuncles.

As the snow melted and the sun retreated, the water froze in sheets of ice along the lane, descending like a toboggan run at the corner near the footpath for the allotments. 2There were yellow sand buckets at each end of the lane but the sand soon ran out.

I was standing by the back door with a steaming cup of tea, looking at the clough when I heard a rumbling from above. A block of snow came sliding down off my sloped roof, landing on the communal pathway and rising halfway up my back window. As I shovelled some of it out of the way I saw that in the field beyond the drystone wall, two kids in red jackets had made a ski jump out of the snow and were snowboarding down the hillside, spiralling in the air.

From the council estate I walked up past the pig farm, climbed up a grassy hill filled with sheep and a couple of hares and reached the top road through a stile built into the drystone wall. I looked down on the village, the tiny circle of the cricket ground and the oblong of the football pitch, the two bisected by the grey line of the footpath that led from the footbridge over the A road and across to where the old red phone box stood next to the post box in the wall.

The Dark Peak was transformed by summer. The blooming of so many trees constituted that change. As I looked across the valley, I could see what happened every July. The field behind my house was a bright yellow, the rape enclosed in its drystone box and made a dazzling golden yellow by the sun sinking through it.

Turning my back to the view from the top road, I went left and through a grey gate and made a gradual ascent of the bridleway, looking to my left across to the moorland, the A road winding in the foreground paralleled by the train line. 3

Going through a tiny gate in the drystone wall that had been completely buried by a snow drift the previous winter, I turned right across the moorland, across shifting sphagnum moss and a hollow from where I could see horses on one side and black cows on the other. I walked uphill to a T-junction of faint footpaths, from where I could look out towards Far Head and The Pike. A single raven spiralled in the up draught, showing the purple in its feathers.

Dropping down, I followed the footpath and sat on a bench, looking across towards the tiny cars on the road far below, heading downhill towards New Town.

The rain had been coming down hard for a week. The cricket ground was a lake, the football pitch reduced to a peninsula and the path between the two impassable. Water ran east to west down the lane, the slight descent of the tarmac and the drystone walls either side funnelling it. Cars with bright headlights sloshed to work and back, the postwoman waded through the water, wheeling her trolley of post and stopping every now and then to wipe the rain from her glasses.

The top of The Churn was cloaked in cloud. Far Head was also concealed by the mist. The trains passed by within sound, not sight. The traffic on the A road splashed in a heightened roar. The electricity pylons reached up into the grey, their tops lost to the cloud, and jackdaws huddled on the wires.

The rain had been sluicing down off the clough and was blocked at the back by the drystone wall, until the water escaped by going under it and re-emerging like a spring through one of the paving stones in the yard. From there 4it collected in a dip in the concrete and came in a channel towards the house, sloshing down the concrete steps by the back door. Thankfully there was a drain on the communal pathway that passed by the back of all the houses of the terrace, and most of the water splashed its way down into that. But then even the drain started to back up and the water became a pond by the back door, getting closer and closer to the lip of the doorway with each day of cloud and rain.

I’d been told about the flood in the 1980s, when the water board had been doing something and the drains had been blocked. Water came running off the clough and flooded the houses on the lane on its way into the brook. The water ran from the pond in the farmyard with the flag of St George above it, and under the houses on the lane, and below the cricket pitch and the A road before re-emerging by the pub.

This time the drains stood up to the strain and after a couple of days of grey cloud but no more rain the water levels in the back yard lowered. The river that had been forming in a rush towards my back door was reduced to a mere stream, and the stream seemed to be escaping down the drain without too big a pond forming on the communal concrete pathway.

Brave enough to risk opening the back door I stood there and saw that the water line no longer reached for the lip of the door frame. All was silent save the sound of running water, and as each day passed that sound reduced in volume until a gentle trickle was lost to the traffic noise off the bypass. I thought I was through it, and I watched a grey heron flapping past the garden shed on its way over the pond where the frogmen had been. 5

I jumped on the train. Getting off I walked up the hill and away from the town in the direction of the moss, before crossing the road and going up the steep grassy bank. Climbers hung from the rocks below me as I looked across the valley to the reservoir. I could hear the cries of the children at the secondary school.

I followed the track along the edge, looking over the drystone wall on my left to the fields of cotton grass swaying on the moss. The music of meadow pipits and swallows played all around as I sat at the head of a grassy descent. That music was joined by the troubled-sounding calls of curlews that echoed from the brook. Through the binoculars I watched their grey-winged flapping and listened to the calls that punctuated the continued music of the meadow pipits and the whistling swallows. I thought of the soft ground beneath the swaying white of the cotton grass fields, and the screaming of the children seemed to rise.

Walking down the hill and cutting through the farm I headed into the neighbouring village, passing the pub there and carrying on along the road until taking a footpath to the right that followed a tunnel under the train line and led to the shores of the reservoir. The dampened path led through trees and alongside the watery ditch of the brook still running down the valley in parallel. That water was blocked from view save for silver shafts of light through the trees.

There were voices of people I couldn’t see and I thought maybe they were fishermen, but when I reached the northern end of the reservoir and looked across the water, I could 6see it was a group of men in red canoes. They looked tiny in the expanse of silver water that reflected the shoreline trees. I thought of the depths below the still surface. Above all stood the bulk of the moss, and the long ridge line with the cotton grass still blowing.

On the lane out of the village there was a caravan covered in ivy with sagging bin liners outside it surrounded by flies. In the yellow light shining in through the back window of the caravan there was a bearded man surrounded by swirling smoke, with two black dogs barking beside him. He smiled knowingly as I passed.

I came up a green hillside that was scattered with sheep wool hanging on to thistles below a sky filled with jackdaws. I crossed the road and passed another farm to stand and gaze at the familiar bulk of The Churn, the dominant hillside brightened, made golden by sunlight breaking through cloud.

The trees in the woods grew thick and rose up to the roadside. They shadowed the steady run of the river as it flowed towards the reservoir. Looking across from the reservoir, the trees of the woods looked collected, condensed, their branches shadowing the undergrowth. In winter, that footpath up through the trees was often bright with moonlight, the sparkle of the stars and the orb of the moon casting a pale glow on the mulch of leaves and weeds.

Above the whitewashed walls of a farmhouse, and beside where the jackdaws roosted in the trees, I stood on the road and watched a rustling in the undergrowth. Orange poppies wobbled. And then the rabbits burst out: one, two, 7three of them. Two of them ran down the hill together and I watched their tails bobbing, while the other one seemed confused. It ran around in circles and then stopped, before running around in more circles and stopping again. Its feet slid on the tarmac on its turns, and when it stopped it wavered from one side to another as though on the verge of collapse. There was something strange about its eyes. I bent down to look closer and it rushed off in circles before collapsing onto the orange poppies.

The village was on the news every night for a week. Reporters stood on the path between the cricket ground and the football pitch, in front of cameras pointing towards the houses on the lane. They stood under umbrellas as the brook rose higher, and the pond continued to deepen below the flag of St George.

She was my neighbour Sheila’s daughter. I’d seen her many times running past the window, often chasing some dog or other. She had blonde hair and seemed to wear pink most of the time and always had a mischievous smile on her face.

The cricket ground began to fill with floral tributes. All day people would park outside the pub and come walking across the bridge over the bypass to lay flowers and little cards with messages of support. Cars weren’t allowed on the cordoned-off lane for weeks.

Sheila would walk down the lane, arm in arm with other women. She’d bend down to read the cards attached to the flowers, kneeling on the grass of the cricket ground in the shadow of The Churn. Cameramen would film the women. I noticed that Sheila didn’t cry. But she rapidly 8lost weight, and when I walked past her on the street she scowled.

A lot of people in the village kept themselves to themselves, just like I did in many ways. In winter, particularly, it was so dark and cold that neighbours rarely saw each other anyway. There were hardly any street lights, and on cloudy nights in winter it got absolutely black, the looming bulk of The Churn indistinguishable from the black skies that surrounded it.

Just at the bottom of the lane, on the corner and near the turn-off for the footpath leading to the allotments, the road went uphill to a rusted iron gate, and beyond that in the field there was a great hole in the ground that looked like it had once been a quarry. In it there were all kinds of rubbish. I’d walked with her down the bank and into the hole and there were washing machines, a smashed and scattered Belfast sink, bags of cement, oil drums, gas canisters, prams, bikes, cracked sledges, broken kites, punctured footballs, a twisted scooter, a blue plastic cricket bat all bent, a tennis ball half sheared.

It was early, just before sunrise, with mist still rising and smells of bracken and the pig farm lingering in the windless air. I zipped my fleece and pulled my beanie hat low over my ears and tucked my gloved hands into my pockets. The front gate squeaked as I closed it. My boots scraped the tarmac on the lane. There was a pied wagtail on the cricket ground, bobbing through the mist. The occasional HGV roared along the bypass.

Leaning on the drystone wall at the bottom of the clough, below the flag of St George hanging above the pond in the farmyard, I looked up at the blackened trees, and 9the silver sky on which the branches were sharply outlined. The jackdaws took off for a brief sortie, swirling in the sky above the cricket ground before coming back to land in the branches of the trees. As the sun came up above The Churn, I knew it was the last time I would see them.

Oystercatchers

Turning the corner past a row of pines and walking down to the boat hut and the small wooden jetty, where two wooden skiffs float with a foot of water in them, Tom looks across the length of the lake. Geese fly in formations and there is the occasional wild cry of a buzzard. There are ducks in the reeds, a pair of grey herons, and blackbirds criss-crossing the lake from one tree to another. He rises from his seat and walks around the far rim of the lake, a place grown over from disuse, a moss of green covering the route through the forest and the tributary paths to parts of an old sawmill. He climbs over branches in the path and glimpses a hind. He passes through the reeds and fallen pines by the lake. There are ducks and geese and buzzards and lapwings and curlews and oystercatchers on the moors beyond. Wind blows through the pines. Light shines through as they sway and creak and brush together. There are dead trees too, as he emerges from under the wavering canopy, with their solid looking trunks and bare branches outlined against the moving clouds in the sky.

11As he sorts through his paperwork at RC Containers, her breasts brush against his elbow.

You’re always out here, aren’t you? he says.

Not always.

You like a bit of rough, is that it?

She smiles again. That’s what you are, is it?

Well, compared to them lot in there.

You’re a bit cocky aren’t you? she says, looking him up and down. Anyway I can’t stay out here all day.

I bet you wish you could.

Nah, I’d rather be in there, she says, picking up the paperwork from his desk and standing there a moment before going back towards the office.

So, what’s your mobile then? he asks.

In his car by the lake there’s the lace of Susannah’s G-string above her jeans, and the small of her back above that as she leans forward. Her seatbelt is tight between her breasts. Tom takes the seatbelt off, and before the car battery begins to get low from all the heating, she moves over onto him.

The curtains change from black to grey. A song thrush goes through its repertoire. Tom opens the curtains. Sociable jackdaws fill the telegraph wires. Coal tits and sparrows bicker in the air beside the feeder.

He thinks of them in the parked car, and how she played with the ring on her finger. He didn’t see the NO PARKING sign, and after they had been there for about an hour, an old man came out of his house. He knocked on the window and said, there’s no parking here, and, can’t you read? Can’t you see the sign? 12

Tom goes into the estate agents and looks at various properties, one next to a church with a belted Yew tree. He drives up the road out of the village, higher and higher so that in his rear view mirror the viaduct leading over the river looks tiny. At the crest of the hill he stops in a parking space. The road stretches in curls across the moorland. Drainage channels shine and there’s a long row of grouse butts. The sunlight falls on a stone building sat alone on the moor surrounded by the sounds of pheasants. He drives on. Golden plovers sit above him on telegraph wires, their plumage brightened by the sun. Great congregations of starlings float by. Lapwings sound like the tuning of an old radio, and curlews whistle too. He drives back along the road over the moorland, passes the turn down the hill for the village and sits in his car looking at the river.

Turning the car around, he drives back towards the top of the moorland. The whole county stretches out below him. There’s a soundtrack of curlews and lapwings and oystercatchers as he drives down the hill to the village. He thinks of her breasts brushing his elbow. He sees another man kissing them, playing with them. He thinks of her enjoying it.

They meet in the car by the bridge over the river and he drives them across the A road. They carry on up the road in silence. At a parking space overlooking the moorland, he puts his hand on her thigh and looks into her eyes.

Look, I’ve been looking at houses for us. We can live high up on the moors where nobody will know us, imagine it? We—

—Slow down. We? she says, her eyes not meeting his. 13

Please, Susannah, he says, passing her a poem as grouse on the moorland fly over butts.

What about the children? she asks.

What do you mean?

I mean, what about the children?

In a field among sheep, there are long shadows of trees and the calls of buzzards and kestrels and curlews and lapwings. Tom walks down to the banks of the river, where there’s a man standing in the water with the current.