Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

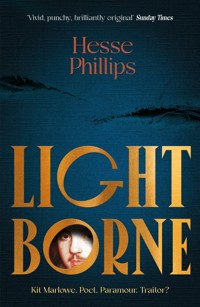

A stunning debut on queer love, betrayal and survival in Elizabethan England. Perfect for fans of Hilary Mantel and Maggie O'Farrell. ________________ 'Vivid, punchy, brilliantly original' SUNDAY TIMES 'Hugely impressive, visceral and moving' FINANCIAL TIMES 'Imaginative, atmospheric, and heart-poundingly tense' NEIL BLACKMORE _______________________ England, 1593. Kit Marlowe is one of London's most beloved playwrights. He lives audaciously, leaving lovers - and enemies - in his wake. But the city's streets are infested with spies. When Marlowe is arrested for treason, heresy and sodomy - all crimes punishable by death - old friends turn foes, bitter rivals emerge, and a stranger becomes Marlowe's dearest ally - if only he can be trusted. In an era where suspicion and duplicity rule, loyalty can be fatal. Richly atmospheric and tenderly imagined, Lightborne is the thrilling tale of an enigmatic, infamous character, and a love that flourishes from the margins. ______________ More praise for Lightborne 'Exerts a powerful pull'IRISH TIMES 'The kind of brilliant writing that rescues historical fiction from the museum' JOSEPH O'CONNOR 'A deeply impressive achievement, meticulously researched and fabulously rendered' NIALL BOURKE

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 637

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Lightborne

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Hesse Phillips, 2024

The moral right of Hesse Phillips to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EBook ISBN: 978 1 80546 038 1

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In memory of David G. Pierce and Paul D. Nelsen

PROLOGUE

6 JUNE 1588

Four years, eleven months, twenty-four days

Marloe admir’d, whose honey-flowing vaine,

No English writer can as yet attaine.

Whose name in Fames immortall treasurie,

Truth shall record to endless memorie,

Marlo, late mortall, now fram’d all divine,

What soule more happy, than that soule of thine?

HENRY PETOWE, THE SECOND PART OF HERO & LEANDER,CONTEYNING THEIR FURTHER FORTUNES, 1598

1

‘KIT, ARE YOU ALIVE?’

The face of Tamburlaine appears through the upstage curtains like a grotesque on a church door, oil-black rings of kohl smudged around his eyes, revealing something of the actor, Ned Alleyn, underneath.

‘They are calling for the author – listen!’

Kit hears nothing but a dull, water-in-the-ears roar that may be a thousand voices calling out or the thundering of his own heart. His fingers make a clumsy gesture at the air around his person, as if to say he has neither will nor strength to step out of it.

‘What, afraid, ye silly giant?’ An arm wrapped in a silken sleeve reaches through and cuffs him on the shoulder, pressing him forward. ‘Go now, go, and take your poison. Now, now!’

The curtains part, cutting a gash of daylight through the backstage gloom. Beyond, the Rose Playhouse appears, a vortex of timber and plaster and densely packed humanity that reels upwards, three storeys, to a dilated eye of cloud-streaked sky. Clad in Mongol furs and turbans, the players dodge aside for Kit’s entrance as if he were ten feet tall and equally wide. With a grand flourish, Ned Alleyn draws his scimitar and waves Kit downstage with the point, like the politest of threats.

Kit ventures a step into the light and sets off a surge of cheers, then chants, one word hammered again and again: Blood! Blood! Blood! Blood! But it cannot be. This is no execution, though Kit stands like a man at the gallows, hands behind his back, balls tucked tight with fear. As his eyes adjust so do his ears, and at last the word becomes clear:

‘More! More! More! More!’

This is what ’tis like to be adored, he supposes, realizing in a panic that he knows not how to perform ‘adored’. No one has yet written odes to his honey-flowing vaine, nor called him ‘the Muses’ darling’, a distinction that shall come to him before the night is out. He is twenty-four years old, the eldest of four children, not counting the dead, and until this moment he has stepped but rarely into the light. Obscurity was safe, but that familiar house has, in one afternoon’s course, burnt down around him. Here he stands in its ashes, exposed and soft and awkwardly tall. He has wanted this, has he not? He has pictured this. It means he has achieved worthiness. It means his old self is gone.

At last, he dips into an inelegant bow, rising with a grin. Adoration, in fact, feels slightly embarrassing, as if he had tripped on a stone and the whole city swarmed to steady him on his feet.

‘Kit!’ Hands clamber at his ankles. Down in the pit are several faces he recognizes, all poets like himself, some friends, others acquaintances at best: Thomas Kyd, Tom Nashe, Michael Drayton, Will Shakespeare. But no sign of Tom Watson.

Kit’s grin falters. He scans the crowd for Tom’s lean figure, his sly smile. He must be here, he must, waiting to clip Kit in his arms and tell him how proud he has made him today.

At Kit’s feet, Thomas Kyd shouts, ‘Jump!’ as if for the fourth or fifth time. ‘Jump down, we’ll carry you out!’

Kit steps down into their waiting arms, on legs like stilts. The poets catch him at the thighs and backside and shuttle him across the pit like a beetle on its back. He twists his head left and right, tries to ask, ‘Where’s Tom Watson?’ but no one hears him, they only deliver him to yet another frenzied handshake, another breathless laud: ‘Seneca reborn – ay, England’s very own Seneca! Shall we have more Tamburlaine?’

‘I—well, if so—’

‘What is your name?’ demands another. And then another, and another.

Kit sputters, having temporarily forgotten it. By the time it comes to him, he is on the move again, and resorts to shouting his own name as if he were only the top half of a man in search of a rogue set of legs, as giddy as a boy riding on his father’s shoulders. ‘Marley! Marley!’

No – he is not even ‘Marlowe’, not yet.

Without warning, a hand grasps Kit’s wrist and tugs him forward with such force that he stumbles onto one knee. ’Tis not unlike Tom to arrive like so, in a whirlwind, and thus, as the hand pulls him upright, Kit expects to come face-to-face with an ecstatic grin, to be wrapped in a jubilant embrace. But the face that finally appears before him is not Tom’s. Not at all.

The man peels a crooked smile back over his half-empty mouth, teeth on the left side and exposed gullet on the right. As always, he looks as if he has lately crawled out of the earth, a fine layer of ash settled over his entire person, a scent of pitch and sparked flint clinging to his shaggy, grizzled hair. Kit has not seen him in months. He had prayed never to see him again.

Kit takes his embrace like a knife to the chest. ‘Did ye burn a candle for me?’ the man says, his mouth at Kit’s heart.

Onstage, Ned has begun the compulsory prayer for victory against Spain. All around, at his cue, the groundlings take off their caps, bow their heads. ‘God bless her Majesty’s reign!’ they chorus.

The embrace slackens. Like most, the man stands no higher than Kit’s shoulder, and yet some part of him, his scent or shadow, looms high above his head. ‘You have been avoiding me, my boy,’ the man says. ‘I’ve sent messages.’

‘God protect her Majesty’s kingdom!’ the crowd intones.

Kit looks not at the pale eyes, only the lopsided mouth, one cheek sunken to the bone. He shrugs lamely at the whole of their surroundings, murmuring, ‘I have been busy.’

‘Of course you have,’ the man says. ‘And you should enjoy this day. ’Tis yours. But Sunday evening, you and I set sail for Dunkirk.’

Kit fears to turn his back on the man, though every nerve in his body aches to run. ‘I have told you,’ he says, too quietly. ‘I do not do that any more—’

‘What’s that?’ The man gestures at the crowd, who are now chanting for death to the Duke of Medina, death to the Catholic Armada, death to the Spanish king.

‘Do ye not hear that?’ the man says. ‘Do ye not hear how sorely our country needs us just now?’ He pauses, head cocked, a wounded sneer upon his lips. ‘Someone has hold of your leash, do they? Who is he? Tom Watson?’

A wave of fear rushes to Kit’s fingertips. He watches a crooked smile spread on the man’s lips, cruelly amused, as if to see a child stumble in its first steps.

‘Old Tom has himself a fine house now, is that right?’ the man goes on. ‘Up in Norton Folgate? And a pretty wife, too. A life like that is a delicate thing for a fellow like him. Very delicate creatures, your kind. A whisper can unravel you.’ The man stands on his toes, leaning close to Kit’s ear. Kit half-expects him to bite it off.

‘I hope you are careful, lad,’ the man says. ‘I hope you know well enough to keep those who might whisper happy. The Council rewards those who whisper, after all. Even one like Tom, with his illustrious friends, even he could be ruined. But you? “Ruin” is too light a word for what they’d do to you.’ He turns his head just enough that Kit’s eye looks directly into his, so close that the pupil appears stretched, like the eye of a goat.

‘Bull’s House in Deptford, Sunday morning,’ the man says. ‘Come quietly; come by river. Who knows? Perhaps you and I will save the kingdom a second time.’

His shadow slips past Kit, behind him, and is gone.

Kit places a large hand over his stomach, disbelieving at first that he is whole, that ’tis not the dropping of his guts to the ground that he feels. He sucks in a breath. He is alive yet.

A celebratory mob of players and poets soon fills the Dancing Bears tavern on Bankside, just up the street from the Rose. Women run half-clothed through the crowd, shrieking like vixens; men pursue them in barking packs. ‘To the Spaniards who’ll fuck our corpses!’ Ned Alleyn toasts, to grim laughter. Just days ago, the Spanish Armada set sail from Portugal, carrying twice the firepower of England’s fleet. Soon, their hulks will be sighted from the southern shores, bursting with some fifty thousand battle-mad men. Victory shall require a miracle from God.

Kit has yet to find Tom Watson, though a host of new admirers have found Kit. After all, he cannot hide; he towers half a head higher than the second-tallest man in the room. Currently he stands pinned between the bar and a pack made up of Will Shakespeare and some of his Shoreditch friends, the former ranting excitedly about King Henry VI, oblivious to Kit’s spiralling panic. ‘To have your hand in it would be a boon to us all,’ Will shouts over the roar of voices. ‘Provided, of course, we all survive the summer. The English parts I shall write, and you, I thought, could write the French parts. For you have been to France, no? You’ve fought in the war, no?’

‘No.’ Something heavy and putrid floats to the surface in Kit’s stomach. ‘Fought, no, not exactly—’

‘But you do speak French.’

‘Ay, ay.’

‘As I’d thought!’ The little fellow looks overheated, wide eyed and red faced, like a hunter who, after a long chase, is poised for the kill. ‘Did you know my father is a glover?’

‘No.’

‘And yours a shoemaker! We shall make perfect collaborators, you see? Or rather, I shall be your pupil, for my verses range wild at times, like fingers over a maiden’s thigh, but you, you know a good foot when you see one—’

‘I’ll be sick.’ Kit hands his cup to Will, shoves past sans apology. The same chaos of faces that had choked the pit at the Rose now form a wall between Kit and escape. After struggling through the crowd, he finally tumbles through a side door and into a low-ceilinged passageway, where he doubles over and vomits into an ash barrel.

The door to the passage opens and closes. Kit feels Tom Watson’s familiar presence even before he sees him: a poet richer in laurels than Kit could ever hope to be, ten years Kit’s senior, nearly as tall and every bit as thin. They look well stood beside one another, Kit has been told, like two portraits meant to hang on the same wall. Tom still wears his big-toothed, vulpine grin as if he’s only just stepped away from his own circle of praise, but after one full look at Kit the grin sinks at the corners.

‘Oh, come now, not this again! Kit, ye cannot do all your drinking ere the night has even begun—’

‘Tom,’ Kit pants, ‘Richard Baines was there.’

Tom stammers, lips pursed as if about to ask, featherheadedly, Who?

‘Richard Baines, Tom, Richard Baines!’

‘Where?’

‘At the Rose – in the pit—’

‘Breathe, Kit.’

‘He knows about us, Tom! I know not how, but he knows!’

At last, understanding dawns in Tom’s gaze, followed by dread. He starts to speak, but behind him the door bursts open, disgorging Kyd, Will, Drayton, Nashe, all in merry pursuit of ‘Seneca reborn’. Deaf to Kit’s protests, they drag him back into the breath-heated air of the Dancing Bears, and he can do naught but watch as the crowd sucks Tom away like a swell.

‘What, long-faced?’ the poets cry. ‘We’ll not allow it! Give us drink, here! Give us whisky! Give us a wench!’ Kit accepts the whisky, declines the wench, and helplessly passes from one man to another like a bridal cup, though ’tis his own cup filled again and again along the way. Soon, a hush flutters over the room: all eyes turn to the stairs, where, one after another, the players climb up and offer toasts to Kit’s health, declare their undying loyalty, and swear up and down that none had ever doubted him, which Kit roundly disbelieves. Before today, he’d barely had a name. Even among the players, he was only Tom Watson’s ‘squire’, Tom Watson’s ‘boy’. Sometimes, Tom Watson’s ‘dog’.

After the supporting players have had their say, comes the great epilogue: Ned Alleyn, still in traces of Tamburlaine paint, minces down the stairs in a yellow wig and a toga, false bosoms swaying against his hairy chest. He introduces himself as Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, and launches into a rambling, falsetto panegyric in Kit’s honour, riddled with tiresome innuendoes:

‘… And to the gallish inkpot, I say this:

Rude vessel, thou art too base a well for dipping

The noble quill that composèd Tamburlaine!

O, that I were such a vessel, darling Kit,

So you would dip in me!…’

Here the clown Rowley puts his arse in the air and blows through his trumpet, lest there be any confusion about what vessel is meant.

Kit finishes his drink and sets off in search of Tom, refusing all further pleasantries along the way. He finds him in the snug, pontificating about Sophocles to an audience of lesser poets and bored-looking whores: Tom Watson, the reigning patriarch of English poets, arms wide open to his legion of clambering children. Many a time Kit has watched Tom hold court at his house north of the river, torrents of jealousy pumping through his heart. But he is mine. They know, and of this they whisper. But ’tis enough that they know: he is mine.

Kit takes a firm hold of Tom’s shoulder and turns him around mid-sentence, very nearly kissing him on the mouth, right there, publicaverunt.

‘Take me home,’ Kit says.

They walk east along Bankside. Across the river, St Paul’s gloomy tower juts out of a pile of gabled houses like a lone pillar out of rubble, its top lightning-struck decades ago, and to this day spireless. Half a mile ahead, a jagged spine of onion domes, parapets and chimney pots marches across the overburdened neck of London Bridge, emitting trails of smoke that bow as one with the wind.

‘They’ll all bethink you terribly ungrateful,’ Tom says.

‘I care not what they think.’ Kit rubs the cold tip of his nose. Even at a tipsy stumble he storms ahead faster than Tom can comfortably follow, weighted down as he is with his prized French rapier. With the curfew in place, Bankside is unusually quiet, and the clanking of Tom’s scabbard resounds up and down the brick embankment as he jogs to keep up.

‘You should,’ Tom scolds. ‘I’faith, you must. Men like us, we live by shows. Why, in a finer suit and with a courtlier air – a French bow, perhaps – you could do far better for yourself.’

‘It matters not, Tom, none of it matters!’

‘You have triumphed today! How can you be angry?’

Kit answers him not. Too frequently are such questions asked of him: Why are you angry? Why are you sad? Why do you laugh? Why do you cry? Other men are never so often called upon to explain their moods, a fact of which Kit has grown painfully aware with the onset of manhood. Howsoever he feels, it is either wrong or too much.

‘Stop, stop.’ Tom loops his arm through Kit’s, dragging him to a halt, and for a moment they stand so close that Kit hangs his head for shame.

Tom embraces him, a gesture not without its dangers. Kit scans the empty street, the embankment walls above. For all these months he’s thought himself safe, he never knew how relentlessly an unseen watcher has fondled him with his eyes.

‘I cannot stay with you, Tom.’

‘Hush.’

‘I must go back to him. What else can I do?’

‘I’ll never let you do that.’

‘Tom, he’ll ruin you. One word from him to the Council, one word—’

‘That man is a fly to me.’ Tom steps back, holds Kit at arm’s length. ‘I know how to be rid of Baines.’

‘How? Will you murder him?’

Tom takes this as a joke. ‘If it should come to that…’

Kit turns a shoulder on him, walking on.

Tom follows. ‘You are not a boy any more, Kit – ’tis high time you stopped seeing Richard Baines through a boy’s eyes.’

Kit had just turned eighteen when he’d first met Baines – not quite a boy, but a man neither. A shoemaker’s son from Canterbury in his second year at Cambridge; a scholarship boy, living on stale bread and beer. Baines was one of Sir Francis Walsingham’s spies just returned from a long imprisonment in France, trolling the university’s halls in search of a swift-footed lackey with a legible hand and a malleable mind. By the time Kit met Tom, which was two years later, in Paris, Kit had grown so accustomed to standing three feet behind Baines that when he closed his eyes he could see the shape of him still, as if he’d stared at the sun.

‘He’s nothing, is he?’ Tom goes on. ‘Just another meddling spy scraping at the dirt. This country is teeming with villains willing to do the same filthy work for less than half his wage, and without the risks that ride upon his back.’

‘The Spymaster cares nothing for those risks. Hell, there are some up at Seething Lane who credit him with saving the Queen’s life!’

‘Ay, none more than himself! Trust me, the Spymaster is but one voice in the Privy Council. And ever since the Archbishop of Canterbury joined, things are changing. Slowly, but they are changing. The days when a spy could disport himself however he pleased, with impunity, are coming to an end. One like Baines – his days are numbered as it is.’ Tom falls silent, gnawing on his tongue. Then whispers, ‘The rumours about yourself and him—’

‘They are not true!’ Kit says, too loud.

‘Well, that is well.’ Tom looks neither relieved nor credulous. Kit may deny the rumours a thousand times; no one will ever believe him. Certainly not Tom.

‘But there were others before you,’ Tom goes on. ‘And there have been others since, though never for long. ’Tis a mainstay of gossip: “Baines and his boys”. Some of them were young. Much younger than you were, at least when I met ye.’

Kit shivers, thinking of a particular room, a particular bed, as repeated across time; an endless succession of bodies in the same place where his own had lain. And yet he says, ‘Does it matter? If it mattered to anyone, would it not be more than mere gossip?’

‘Well,’ Tom says, ‘when gossip becomes troublesome…’ He shrugs again meaningfully, showing a nervous grin.

Kit sighs. ‘What would you have me do?’

‘Tell the Council a beastly thing about Baines. Tell them a thing they are already likely to believe.’

‘No!’

‘Fear not,’ Tom says, as if to soothe an overly imaginative child. ‘Tomorrow I will take you to Seething Lane, to see Thomas Walsingham. He’ll speak with his uncle for you.’

‘That man makes my hair stand on end,’ Kit says. Thomas Walsingham had been Tom’s lover when Kit first met him: nephew to the Spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, and widely expected to take his uncle’s place one day.

Tom laughs. ‘Only because you do not know him. But I think he still loves me, the poor wretch! He’ll believe you, for my sake.’ He leans closer, reassuring. ‘Of course, the matter will be kept quiet. Belike the Spymaster shall send Baines off to serve in some hellhole abroad, or at the furthest end of the kingdom. But the devil would be out of your life, forever.’ He pauses. ‘You do desire that, no?’

‘I do,’ Kit says, though it feels like stepping into blackness with his hands outstretched.

‘And if’ – Tom steps forward, grasps Kit’s hand – ‘if, Kit, Baines means what he says… You must speak with the Council before he does. It cannot come from me; it must come from you. You understand that? You understand why we must go tomorrow?’

Tom’s grip is tight, his fingers threaded through Kit’s. ‘I do, Tom. I do.’

Tom lets out a breath. They walk on for a time in silence, heads bowed, hands clasped. But as the seconds pass and the light over London Bridge’s southern gatehouse grows stronger, an invisible knife sticks between Kit’s shoulders, sharper with every step, and does not let up till they let go.

Soon, the embankment sweeps upwards to meet the torch-studded hulk of Great Stone Gate, its crenellated ramparts busy with soldiers, as sheer and stern as a promontory on the threshold of the sea. From atop the towers and hanging over the portcullis, thirty human skulls roost in varying stages of preservation, slack-jawed like a row of mute choristers. One of the skulls had belonged to a man who would, perhaps, still be alive had it not been for Kit and Baines, for better or for worse. His skull takes pride of place on the gate, beetling over the archway on a long, horizontal stave, so that to enter or exit London is to pass beneath its eyeless stare. The jawbone swings wide, a scream frozen in time.

On the causeway, Tom pulls Kit behind a parapet, out of the guards’ sight. ‘I would kill Baines for you, if you were to ask it of me. ’Tis no less than he deserves.’

Kit shakes his head. Death is senseless, pointless. Many would say that the man whose skull now hangs above the arch had deserved to die. But his death was beyond death, beyond senselessness; Kit saw it with his own eyes. It was obliteration.

In any case, vengeance is of no use to the powerless. Kit’s only aim is to survive.

Tom nods at Kit’s silence, steps back. ‘Exile it shall be, then.’ He touches the tip of his tongue to the backs of his teeth, his habit when working over some delightful treachery. ‘Where shall we send him? France? The Low Countries?’

‘The Low Countries,’ Kit blurts. Baines had always hated it there. It would be as good as sending him to hell.

‘The Low Countries!’ Tom laughs. ‘You have a tint of spite in you.’

Kit shares not in his mirth.

Tom cuffs his arm gently, in that estranged manner he adopts whenever they are watched, or he presumes them to be watched. ‘Come now, why so serious? What did he do to ye, to make ye so serious?’

Kit thinks, immediately, of Paris: candlelight on his desk in the underground cell. A man’s scream, followed by a squelch, a crunch. Baines’s face leaning into the light as he dropped an object onto Kit’s desk which oozed darkly onto the blank papers: a finger, the nailbed black with filth.

‘Put that up your arse,’ Baines had quipped, and then returned to his work.

‘Kit.’ Tom touches his arm; the touch stings. His amber eyes look on Kit’s startlement with kindness, but also urgency. ‘Tell me what he did to you,’ he says. ‘Tell me as you will tell it to the Council.’

On a December night three years ago, in the cellar of a large house on the north side of Paris, Kit and Baines had climbed through a trapdoor, held open above their heads by a thin man with nervous eyes. Just before shutting the door, the thin man had handed Baines a lantern, in whose light Kit could see their own breaths. Underfoot, a creaking ladder plunged deep into the hollow-sounding earth.

‘This is where God’s work is done,’ Baines had said, descending.

At the bottom, they’d found the first and largest of many pickaxe-scarred chambers. Candles flickered in niches in the chalk walls. Haggard, pallid faces greeted them, boys and men, their hands cupped around bowls of gruel. A boy was singing softly, Glory to Her righteous name, and it echoed like plainsong from the choir of Bell Harry.

They were soldiers, but they bore no weapons; they were at war, but the war had, in the fifteen years since its beginning, become a bloated, misshapen thing, defined not by borders but by faith. By Papal decree, certain salvation awaited any Catholic who could put Queen Elizabeth’s papist cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, on the English throne, a promise that no Catholic in England or without could take lightly. Some years earlier, Baines had infiltrated the infamous English seminary at Rheims, where exiled Catholics trained for holy war against their own homeland, but he had bungled the mission terribly: allowed himself to be caught, and lost half his teeth to the papists’ torturers ere they let him go. This mission to Paris was a chance for Baines to redeem himself, for one of the seminary’s men had been captured.

A superior led Kit and Baines to their charge, explaining on the way: the prisoner was known as ‘Number 4’, a follower of the fanatical Jesuit order – ‘Cornelys’ he called himself, though he was a Staffordshire man by birth – one in a vast web of couriers secreting messages from the imprisoned Queen of Scots to her followers abroad. Many believed ‘Number 4’ knew the name of Mary’s contact in London, but all efforts to prise it out of him had thus far come to naught.

‘Ha,’ Baines said, ‘give me an hour!’

They descended yet another ladder into a reeking pit, ten feet deep, equally as wide. The prisoner was chained to the wall by the wrists and eerily waifish in appearance, having only a few patchy wisps of beard, the berry-coloured lips of a boy, though it was said that he was older even than Kit is now. With a gesture of implied generosity Kit was shown his desk, a thing almost obscene in its Frankish elegance, a frost of white mould blooming from the narrow, turned legs. He’d nodded as if to say he found it acceptable.

Baines’s instruments were somewhat different: tools of metalsmithing and surgery, awls, pliers, vices, shears.

So began the longest eight days Kit has ever lived. The Council had but one question that needed answering – the same question they always asked, in one form or another – and Baines never tired of asking it: ‘What was his name?’ From morning prayers till suppertime. ‘What was his name? What was his name?’ The prisoner would roll in his own shit to deter them from touching him. He would call the Queen a witch and a whore, call her ministers arse-licking pandars and her bishops a mob of sodomites. But he never uttered a name.

Nevertheless, every night Kit had to carry his interrogation notes, such as they were, to a victualling house owned by secret Huguenots on the far side of the Seine. There, Kit would go around the room with a pitcher, filling cups like any pot-boy, till he came upon a boisterous table occupied by seminary students, and among them, two of the Council’s spies: Thomas Walsingham, nephew to the Spymaster himself, and Tom Watson, a poet whom Kit had long admired. It was there where, one night, after Kit had passed his notes to Walsingham under the table, that Tom had caught him by the wrist and dropped a little pie into his hand: buttery crust, rich beef filling, the most delicious thing Kit had ever tasted.

‘If you ever need anything, lad,’ Tom whispered. ‘Anything at all.’

By then, Baines was growing impatient. During the next day’s session, without warning, he picked up a set of tinker’s shears and cut off the prisoner’s index finger. Tossed it, still bleeding, onto Kit’s desk. ‘What was his name?’ Baines repeated, over the howls of pain. ‘What was his name?’ and then another crunch.

Kit sat with his fingers over his eyes, the heat of his own whispers on his palms: ‘“The light of the body is the eye, therefore when thine eye is single, then thy whole body shall be light…”’

‘What was his name?’ Baines snarled.

‘“… then all shall be light, even as when a candle doth light thee…”’

‘What was his name?’

‘“… be not afraid of them that kill the body, and after that are not able to kill the soul…”’

‘What was his name?’

‘Babington!’ the prisoner screamed.

Baines paused, as if slapped. He squeezed the prisoner’s pale face in one hand, and with the other snapped his fingers at Kit. ‘What was that?’

‘Babington! They told me his name was Babington!’

Kit put the quill to the paper and watched it quiver. The ink had dried. Out of reflex or madness, he dipped his quill in the blood that pooled from the prisoner’s finger, and tried to scratch it down:

Babington.

The men who brought Anthony Babington down still make much of themselves, as if they’d dragged the fabled leviathan onto the beach by one of its several tails. In truth, Babington was merely a courier, a scribe, same as Kit. But the missives he’d delivered were between the Queen of Scots and a pack of her sympathizers based in London, lackbrains really, who were neither discreet in their schemes nor in those whom they invited into their confidence, Babington especially. Finally, after over a decade of looking for an excuse, the Council would have Mary’s head, thus exterminating the last living hope of a Catholic England.

Within eight months of Kit scribbling the name Babington in blood, Mary, Queen of Scots was sentenced to death. Her seven conspirators were strapped naked to sledges and dragged through a stone-slinging mob that stretched three miles, from the Tower of London to the church of St Giles-in-the-Field. Babington arrived at the gallows with the tip of his nose and both earlobes sliced off, one eye-socket shattered, his hair matted in gore. When they pushed the sledge upright to display him to the crowd, he collapsed to his knees and made the sign of the cross with crabbed, black-fingered hands, ruined by the rack. He was twenty-four years old. Two years older than Kit had been then. The same age Kit is now.

Standing fifty yards from the stage, Kit had been able to smell him.

‘You see that fellow, up there?’ Baines had said, pressed close to Kit in the crowd. He was not pointing at Babington, but at a smallish man with a clean-shaven face who stood among the prisoners at the back of the stage and yet did not appear to belong to their number, his aspect subdued, his clothes tidy.

‘He’s one of ours,’ Baines went on. ‘Goes by Robin Poley, he does, but Babington called him “Sweet Robin”, “Dear Robin”, “Robin my love”.’ Baines grinned, exposing his half-set of teeth. ‘Babington wrote him a love-letter, just last week!’

‘Blood!’ the crowd roared. ‘Blood! Blood! Blood! Blood! Blood!’

Kit had seen executions before. This one dragged on far longer than most. The light changed, the shadows lengthened, the bells rang brickbats-and-tiles, and Babington’s screams went on, as urgent as the gushing of an artery. He’d started out praying, but in time the only intelligible word left on his tongue was ‘Mama’. He did not die. He unravelled, from a man to a boy, a boy to a child, a child to an infant, which little by little turned animal: a screeching, writhing, comfortless thing, a faithless thing, for whom the word ‘God’, as all words, meant nothing.

Through it all, Kit found himself watching the man with the clean-shaven face, who in turn watched Babington die, with a faint smile fixed at the corners of his mouth. Sometimes, Kit had thought the man’s lips looked pale, and once or twice he’d noticed him swallow hard, but never once did the man glance away. When it was over, he’d sighed, as if having eaten his fill.

After a full seven such executions, lasting till sunset, a horde of blood-drunk spectators had repaired to the nearest row of taverns, filling every house with their jittery, overloud recapitulations of the spectacle just seen. Baines had dragged Kit from one tavern to the next, till midnight found them settled in over a full jug of brandy, celebrating their success.

At some point Kit had vomited all over the table and Baines and himself. Immediately afterwards, he’d begun to sob: back-breaking, rib-bruising sobs that made him want to tear his own eyes out. And I say unto you, my friends, be not afraid of them that kill the body, and after that are not able to kill the soul. But Kit had seen it – he’d seen it – he’d seen the soul die. He knew now that it was possible.

Baines had flicked his gaze at his cup and tossed the contents to one side. He patted himself down with a handkerchief, which he then offered to Kit. ‘There, there now,’ he’d said, refilling his cup from the jug.

Kit had mopped the table first, then himself, before he’d gathered enough breath to say, ‘I can no more of this, I can no more – I want to resign!’ He took hold of Baines’s wrist, splashing brandy. ‘Please help me! Tell them I am unfit. Tell them I am a coward. Tell them anything, I care not what. Make them let me go!’

Baines had indulged him as he went on, for another minute or two. But then he’d begun to relate details of Babington’s capture that Kit had known not of before, and of the man with the clean-shaven face, who some called a hero and others called, sneeringly, ‘Babington’s widow’. For not only had Babington written him love-letters and called him fond names: it was also said that Babington had given him a ring – a diamond ring, which he never took off. Not even now.

‘I do not begrudge you your affliction,’ Baines said, after a deliberate pause. ‘Lads like yourself have ever been exceptionally useful to the Council. You do as you are told. You keep secrets well. That is why, for the time being, you are protected, your crimes indulged. But only if you remain useful.’

He knew everything, of course. Kit had never confided in him, but there was no need to do so, not in words. Kit had any number of words for the things he’d done with the other lads at university, and, before them, a neighbour boy from Canterbury, and before him, a seventeen-year-old apprentice with whom Kit had shared a bed when he was just thirteen; who, one night, had taken Kit’s hand and fitted it around something hard and warm under the covers, and said, ‘I’ll do you if you do me,’ and whose face Kit’s father had smashed into an eyeless wad of blood and teeth ere he’d hurled him into the street. What Kit lacked in words was in the scream that had stuck silently in his throat as he’d watched the apprentice’s features dissolve into a scarlet smear and realized that such would be his fate too one day: to be obliterated.

‘I understand,’ Baines said. ‘I know you cannot help it. Once that devil is in you, there’s no getting it out. Most would say you are poison in the blood of Creation, a heresy made flesh, and that is why you must be purged. But I think your lot is sadder than that. Whatever part of you God made is gone now. That must be terrible, for if you are no longer of God’s making, then neither are you of Creation. You are a bugbear. A trick of the light.’

Kit knew not whether that was true. What Baines said next, however, was no lie:

‘Understand, a fellow like you has but two options. One you have just witnessed. The other is to serve.’

2

PAST MIDNIGHT, KIT AND Tom cross London Wall at Bishopsgate in the north, and soon after arrive at a gabled cottage on Hog Lane, Norton Folgate, commonly known as ‘Little Bedlam’. Though the name was intended as a slur, Tom has embraced it, for after all the house is bedlam on the best of nights, with its ever-changing roster of players, poets and misfits. Six currently lodge in the attic, more than the law allows for a private house, but Tom need not fear the law; he still has powerful friends.

The nightly curfew shall detain Little Bedlam’s other lodgers at the Dancing Bears in Bankside till morning. Inside, Kit and Tom find Anna Watson sitting alone upon the stairs in her nightgown, a single candle puddling at her feet, a gory clot of red yarn dripping between her fingers. She smiles her tipsy smile as she descends to meet them, stands on her toes and kisses Tom’s mouth as if to bite into a ripe fig. ‘The bed was cold without you.’

Tom and Anna stand with their hips almost touching while he untangles the knitting from her fingers, enquiring after her night, her supper, her prayers, looking as if at any moment he’ll put her fingers in his mouth and suck them. Once freed from her handiwork, Anna turns her attention to Kit, stroking him beneath the chin like a favourite pet.

‘Did they love you?’ Her pupils gape at him, solid black, her breath sickly-sweet with the sleeping potion from which she takes sips all day, every day, whether she would sleep or no.

‘I think they did,’ Kit answers, trying to smile.

Behind her, Tom grips the banister, ready to ascend. His eyes hold fast to Kit’s. Tonight, they say.

The waiting begins. Kit takes some water out to the privy and spends far more time than truly necessary washing up, and then creeps upstairs, past the closed door of Tom and Anna’s bedchamber, the sound of her anxious murmurs and Tom’s soothing replies. In the attic room, Kit huddles, shivering, beneath the blankets, ears attuned to every soft creak of the house’s cooling timbers, waiting for a footfall on the stairs, for a shadow to rise through the trap in the floor. He half-expects to see Richard Baines appear. Indeed, to his shame, a part of him longs for it. Another chance to plead, to bargain, to fawn. To barter for liberty, with pieces of himself. Perhaps there’s no remedy for one such as him, who had learned to love first by loving a father who had terrified him, second, by loving God, whose love can never be declined or refused. A child of God never truly owns his body. If God says, ‘Give it to me,’ it must be yielded.

By the time the trapdoor creaks open, Kit is near frantic. ‘She was restless,’ Tom whispers, kneeling upon the corner of Kit’s bedroll, lined up in a row of other such bedrolls, all empty. He slides himself over Kit’s body like the closing of a lid, and in the darkness kisses him, with urgency of purpose. ‘Come now, the others shall not return for hours yet.’ Through his nightshirt his body is hard and lithe and straight, a pine curtained in mist. Moonlight gleams in the whites of his eyes, silvers the small hairs of his beard.

‘You belong to me,’ Tom says. ‘I will keep you in a golden collar.’ He always says suchlike things, words of lordship and conquest, of benevolence and magnanimity. Facedown, with Tom’s hot mouth on the nape of his neck, Kit could be a ruby, a crown, a kingdom, a spoil of war coveted and plundered. How he has yearned to be captured. To be possessed. Waiting has bred a kind of bedlam in him that gushes forth unabashed, raving of his desires with a voice made hoarse as if from screaming.

‘Shh.’ Tom covers Kit’s mouth. ‘Someone will hear.’

Let them hear, Kit thinks. Let the world hear. Eyes closed, his fingers squeezing the back of Tom’s thigh. He lets his soft moan travel through Tom’s fingerbones like a song through guitar strings, vibrating all the way to the heart.

Nay, this is what it is to be adored.

‘Did you tell me the truth?’ Tom says to him afterwards, when they lie facing each other, Kit almost asleep.

Kit knows what he means. On the way to Little Bedlam, he had told Tom a story he has told no one else: a bedroom in a house on Deptford Strand. Baines’s hand burning like a firebrand on the back of his neck.

‘I tried,’ is the best Kit can answer.

‘He is a monster.’

To this, Kit has nothing to say. Years, he has left these waters undisturbed, now doubt clouds his mind like silt. He is not the only monster.

‘I am afraid,’ Kit says at last. ‘He can destroy me, Tom. And he will. One day, he will. He knows things about me, things I fear even to tell you… They would put my skull on the gate, if they knew!’

‘Nonsense.’ Tom strokes Kit’s cheek with his thumb as if to wipe away a tear, though there are no tears. ‘Your mind is prone to extremities. Know ye not how rare a thing it is to spend eternity on Great Stone Gate? You are as likely to be born with eleven fingers.’ Kit smiles, but after a little silence Tom says, ‘What things? What can you not tell me?’

Now there are tears.

‘Listen to me.’ Tom’s hand sweeps over Kit’s face, his hair, his shoulder. ‘This man must go. Thomas Walsingham will help us. But understand, the story you have told me will not be enough. ’Tis dreadful, yes, but some may not see it as you and I see it. When we meet with Thomas tomorrow, you shall have to call that darling muse of yours into it, ay? I know you have a talent for that, for horrors.’

That word ‘horrors’ resounds, so limitless. ‘I like it not, Tom. You know him not as I do—’

Tom lifts Kit’s head by the chin. ‘If you do this, you will never have to fear Richard Baines again. We will go on as we are, and in little time every Jack and Jill between Penzance and the River Tweed shall know the name Christopher Marlowe, and I shall grow jealous and resentful and fat.’

Kit laughs, for he loves this in Tom, the ease with which he assumes greatness, colours the world as he sees fit. He even loves the way Tom mispronounces his name, not shrinking ‘Marley’, but bold, round ‘Marlowe’.

‘I will love you,’ Tom says. ‘I will admire you, as I did today.’

’Tis rare that Tom says ‘I love you’. Those words arise out of want, cousins of I hunger, I thirst, I ache, a reminder that joy is fleeting. But God above, how richly one may live within the stark circumference of an hour!

Nay, Kit shall not permit any man to threaten this life, such as it is, so beautiful and so cruel. He will defend it to the death.

Two days later, as Sunday services end, crowds flow forth from every church in the city, converging on the eye of the Rose Playhouse. The pit fills in less than five minutes. Such a crush forms at the doors that the grooms cannot force them shut. The name flies through the crowd, from lips to lips, in doubt and wonder: Tamburlaine. No one has ever seen a play like it, splendid, ghoulish, perfumed in Orient spices and daubed in barbarian blood. Tamburlaine is a beautiful monster, a silver-tongued savage. Like spilled ink, he bleeds across the map of the world with his ever-growing army, neither conqueror nor king so much as Death itself:

Now clear the triple region of the air

And let the majesty of heaven behold

Their scourge and terror tread on emperors!

In the same moment that Tamburlaine calls for his soldiers to slaughter the virgins of Damascus and hang their corpses on the city’s walls, four miles downriver in the village of Deptford, a rabble of helmeted guards – mercenaries, really, like all the city’s guards – break down the door of a house on the Strand. A woman screams, children cry. The master of the house, a stout, grey-haired man called Bull, blocks the foot of the stairs and demands a warrant. He is answered with a truncheon to the temple. His wife catches his body as it falls.

In a bedchamber upstairs, the guards find Richard Baines with one leg already out the window.

All hands wrest him backwards. They shove him facedown, manacle his wrists, pull a black hood over his head. ‘I am here on the Queen’s business!’ he cries. ‘Take me to Thomas Walsingham! Take me to Sir Francis! They’ll have your heads for this, ye jades!’

A guard replies, ‘Whom do ye think sent us?’

One man links an arm through each of Baines’s arms and together they drag him downstairs, two more men in front and two at the rear. In the corridor below, Madam Bull sits on the floor with her husband’s bloody head cradled in her lap, two boys and a girl clinging to her pooled skirts. One of the cutthroats drops a bag of coins on Master Bull’s chest.

‘Apologies from Master Walsingham.’

The rest haul Baines outside and bundle him into the back of a wagon. ‘What did he say about me?’ Baines asks. No one answers him. ‘What did he tell you? The boy is a liar, I say!’ They close the gate, make ready to go. Baines writhes about the wagon-bed, his hood pulsing in and out with his breaths. ‘I tell ye he is the Devil! A traitor! An abomination! Take me to Sir Francis, let me tell him the truth about Kit Marley!’

On Bankside, Tamburlaine comes to an end – happily, by all accounts, with the conqueror’s own wedding solemnized amidst the Damascene ashes – and applause erupts out of the Rose’s open roof. When the cries for the author arise, Ned Alleyn announces him, ‘Christopher Marlowe!’ and at once a lean colossus strides out from behind the curtains, auburn hair swept back, a pearl in his ear, his humble russet suit concealed beneath a cut-silk half-cape that some in the pit recognize as belonging to Tom Watson. At the edge of the stage he swoops, elegantly, into the French bow that he’s spent the past two days practising.

Kit stands upright, looks over the cheering mob. A single human face, a single human stare can often overwhelm his senses, and here they number two or three thousand. He cannot pick out any one face he recognizes, not Tom, nor the other poets. He searches for Richard Baines, despite knowing what had happened in Deptford just minutes ago. Already, a part of him suspects it was a mistake. He feels a clench behind the ribs, as if at the setting of a fateful clock.

From this moment forward, Kit has less than five years to live. Even now, there are three men within the audience who will be with him when he dies, all of whom are still strangers to him:

Seated up in the first gallery, a man with a clean-shaven face called Robin Poley climbs Kit’s body with his eyes, smiling in satisfaction, as if after a rich and lovely meal. As he applauds, a ring flashes upon a finger of his right hand: a large diamond, shaped like a tear.

Ten feet below Poley, in the pit, a burly, long-haired ruffian of twenty-one named Nick Skeres wraps a meaty arm around the neck of his much smaller companion, pretending to strangle him. ‘Look at you!’ he teases. ‘Lovestruck, you are!’

Wriggling free, Nick’s friend – Ingram Frizer, also twenty, and as scrawny as the other is big – stands on his toes to see the stage. He trembles as if battle-giddy, his boyish, large-eyed face fixed in a mad-dog grin. For indeed, this is love that Frizer feels, for the very first time, love for a thing that cannot love him back, a thing he may only regard from afar, in wonderment. He is in love with Tamburlaine, in love with a play. Its words fill him, animate him, as a hand fills a glove: Smile, stars that reigned at my nativity—‘What is Beauty,’ sayeth my sufferings, then?—I that am termed the scourge and wrath of God, the only terror of the world!… Words like meat, to be chewed over and savoured; words that taste, deliciously, of blood.

That this man who now towers at the foot of the stage was Tamburlaine’s author, Frizer can readily believe. Just look at him! – he is the embodiment of those words. He is not so much a man as the fever-dream of a mad philosopher, a crazed poet, a deluded lover. Magnificent, Frizer thinks. He is magnificent!

Four years, eleven months, twenty-one days from now, Frizer’s hands will be so caked in Kit Marlowe’s dried blood that they’ll crack like clay.

6 MAY 1593

Twenty-four days

[Ingram Frizer] was something to Marlowe but we do not know what… The only link between them that we know for sure is that they shared the same ‘master’, Thomas Walsingham.

CHARLES NICHOLL, THE RECKONING, 1992

3

TOM WATSON IS DEAD.

And so, Kit’s latest play is half an orphan, at least in his mind: Edward II, the child of Tom Watson, and grief. Now, it shall be the last play performed before the same plague that killed Tom shutters London’s theatres for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps the looming catastrophe is a good omen. For the play, at least. Four years ago, when Tamburlaine had made the name Christopher Marlowe famous, the whole country had believed they would be either dead or bowing to the Spanish king within the month! Every rich merchant loses a ship sooner or later, but thus far Kit has never come close. Tamburlaine’s sequel was even more beloved than its predecessor, despite its eponymous hero coming to a bad end; the people marvelled at Doctor Faustus, though many called it blasphemous; they came in droves to see The Jew of Malta, The Massacre at Paris. Like Kit himself, Edward II was a difficult birth, but many difficult births thrive thereafter.

Fifteen minutes into the first act, the first of many cherry-stones is spat at the stage, landing almost unnoticed by the players’ feet.

By the final act, the pit is on the verge of rioting. Much of the galleries have emptied. Those who remain have stayed only to see the highly anticipated climax: Edward II, the sodomite king, impaled through the anus with a red-hot spit. Two hours, they have waited to see the miserable bugger die, but the killer hired to do the deed draws the matter out past all endurance. Shouts of ‘Get on with it!’ and ‘Go to!’ well up, while onstage the murderer dallies with his wretched prey, a cat with a mouse. He even offers to go at one point; ’tis the king who begs him not to: ‘for if thou mean’st to murder me thou wilt return again. And therefore stay.’

The ragged king then kneels, tugs a diamond ring from his finger – his last possession – and slides it onto the killer’s hand. The killer smiles, just at the corners of his mouth.

At last, someone hurls a clod of dung at the stage, nearly missing the murderer’s head. A bombardment follows: insults, refuse, stones. One by one, the besieged actors take flight, first the killer’s two accomplices and then the killer himself, flinging down his unused roasting-spit with a clang.

Bravely – stupidly, perhaps – King Edward lingers, shielding his head with his arms. ‘Good gentles – good gentles, I pray you, ’tis nearly over… Let us finish!’

He is struck square above the eye by a handful of horseshit. A voice in the mob cries, ‘Hang them!’ and soon the rest follow suit.

Through a crack in the upstage curtains, a dark eye watches it all unfold. Kit Marlowe lifts a silver flask to his lips and drinks.

Less than a week later, Kit is startled awake by a crash, the slamming of one heavy, solid object into another. He lifts his head from the pillow with a suck of air, still drunk from the night before. Downstairs, the crashes continue. Kit lies still, listening without comprehending, his gaze stumbling over the unkempt lodging-house room where he has lived the past several months: the unwashed bowls and cups, the laundry draped over every available surface. The empty bed across from his own, where Thomas Kyd usually sleeps.

At last, he hears the front door give way with a crack of splintering wood. Boots tromp inside. A man’s shout from the room below. The landlady’s scream.

Kit reels to his feet but freezes in place. In the doorway of the bedroom, a bearded mongrel paces and whimpers, its wet brown eyes big with worry. The light is grey and rainy, just after dawn.

In the kitchen directly below, boots rumble back and forth, objects crash and shift. There comes another scream, a man’s: Thomas Kyd, whose pleading Kit hears through the floor: ‘What have I done wrong? What have I done?’

Kit snatches up a leather satchel from beside his bed, grabs some clothes off the floor and shoves them inside. He sprints into the room across the corridor and falls upon the cluttered table therein, scooping papers into his arms. Boots ascend the stairs; voices shout commands on the way up. Kit darts back into the bedchamber just as their shadows round the first landing, papers scattering behind him, the dog barking and dancing at his heels. He takes up his doublet and boots, throws the shutters wide open and hurls himself into thin air, plunging two floors down to the bare, black earth.

Hurt, though he knows not where, Kit scrambles to his hands and knees, lopes four-footedly to the fence and clambers over it like a cat. He can still hear the dog barking as he tumbles into the alley beyond. A second later, silence.

Kit runs barefoot into the next alley, sidles in with his back to the wall. As he puts on his boots he discovers a gash in his right knee, blood and dirt streaming down his shin. The lodging-house is just two doors behind him; he can still hear the shouts. Around the corner, a heavy object explodes against the ground and Kit needlessly shields his head.

He peers around the wall with one eye. A wooden casket lies in splinters in the street, weltering in old clothes and loose paper. The air is dense with the sweet, white smoke of a plague-fire, yet through it Kit makes out the shape of a wagon and two men, one holding the rearing horse by the bridle, the other bouncing on his heels, stretching his neck to see inside. He seems to make a joke to his companion, and then, turning his head in Kit’s direction, the smoke parts just enough to reveal a hint of his unmistakable face: the sunken cheek. The crooked mouth.

Kit’s legs become water. He shrivels into the alley, stifling his own shout behind a hand. For far too long he cowers, whispering curses and pleas up to the sky, but at last the front door of the lodging-house bursts open, unleashing Thomas Kyd’s screams. Kit runs.

He pelts south through the empty streets, afraid to look back. Eventually the smoke in his lungs compels him to stop, doubled over and fighting for breath. His hands shake as they reach for his flask, in desperate need of a drink, one drink, to steady his nerves…

His flask, he realizes, he has forgotten his flask!

He could fall to his knees and weep. Tom Watson gave him that flask, not that it matters now. There is no time to mourn, not for a flask; not even for Thomas Kyd, nor the life Kit had valued but little till this very moment. Richard Baines is back.

Kit limps on towards London Bridge. Ten miles. That is how far he must run. Ten miles south, past Southwark, Deptford, Blackheath, Eltham, Chiselhurst, to Scadbury, and Tom’s former lover, Thomas Walsingham.

By midnight, rain pours over Scadbury Manor, a great half-timbered house built upon the bones of a Norman fortress, with a two-mile-wide bulwark of forest on every side. Up until three years ago, the house had rarely ever seen its master, who was formerly Sir Francis Walsingham, also known as her Majesty’s Spymaster. Now, months have passed since Scadbury’s new owner, the late Sir Francis’s nephew Thomas, last left its sheltering walls. Even in darkness, he sits awake in his study, poring over the letters his eyes and ears in London have lately sent, many of which are concerned with the recent, abortive performance of a play in Shoreditch, of all things. Walsingham is no longer a spy; no longer anything at all, despite his storied lineage. Still, he knows already of Thomas Kyd’s arrest this morning; moreover he knows, with the sick certainty of poison in the belly, that Kit Marlowe could arrive at Scadbury at any minute.

Inside a cramped stone sentry-box built into the house’s western flank, Ingram Frizer huddles into a too-big coat, watching blades of rain streak through the light of his lantern like meteors, from blackness to blackness. He has been here since sundown. To pass the time, he spins a knife in his deft fingers and murmurs whole speeches from Tamburlaine to himself just above the rain, luxuriating in each sibilant: ‘“There sits Death, there sits imperious Death, keeping his circuit by the slicing edge…”’ His little knife, just eight inches long, he imagines to be a scimitar. His tongue, he imagines, is made of steel.