2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Uri Jerzy Nachimson

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

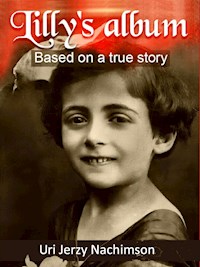

Lilly’s Album is a story based on the trials and tribulations of a Jewish family that takes place between the First and Second World Wars. The book was written by Holocaust survivor’s son, Lilly's nephew. This is a heart-rending tale of the journey from youthful hopes and dreams to the edge of despair and eventual death. This Holocaust story is about burning love, the futility of war, and the extermination of innocent people because of different beliefs. Based on a true story, it took three years doing Holocaust research and numerous travels to Poland, where the novel is set, to make sure that the story is authentic.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Lilly’s Album

Novel based on a true story

By Uri Jerzy Nachimson

Copyright © 2016 by Uri J. Nachimson

All rights reserved.OW Ref #91230 dated 2016-02-04 09:01:07

Original language: Hebrew

English Title: Lilly's Album

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. For further information, contact [email protected].

The book is based on a true story, but some of the characters in the book are the result of the imagination of the author including parts of the plot. Any resemblance between the characters and real people, is purely incidental and does not imply any connection between them.

Treblinka

There is no voice as sad as the wind at Treblinka.

Eyes we have but see not, ears we have but hear not.

Only the heart knows and it shudders in silence.

Only the wind was kind, shrouding their ashes

In the crevices of the earth, gently covering.

When the world turned aside, only the wind gave eulogy!

In mercy we are spared of the everlasting wails.

In death, too, these cheated, but not forgotten;

The wind, the moaning wind, sentinel of the dead.

It shall bide here, beating its wings in sorrow!

(Dedicated to Lilly by Edwin Vogt, 2000)

To properly mourn my family I had first get to know them, so I raised them from their unknown graves, brought them to life, and then let them die with dignity.

(Uri Jerzy Nachimson)

Main Characters in the Book:

Wolf and Ida Nachimzon: parents of David, Lilly and Izio.

David, Lilly, Izio: children

Eugenia, Roza, Cesia, Emma, Berta, (nee Friedberg)Muniek: brother and sisters of Ida

Stanislaw Szajkowski: husband of Eugenia

Paulina Nachimzon, (nee Wolfson): Wolf's mother, sister of Juliusz Wolfson.

Izabela Grinevskaya: Ida's aunt (pen name of Berta Friedberg)

Moses Samuel Wolowelski: Cesia's husband (father of Adam and Jerzy)

Adam Wolowelski son of Moses and best friend of David

Jan Sosnowski: Count from the village of Maluszyn

Zosia Szawlonska: Polish neighbor (Ewa's mother)

Fela Goslawska: Lilly's friend from Warsaw

Irena Oleinikowa: David's Polish girlfriend from Wloszczowa

Klara Feinski: David's Jewish girlfriend from Warsaw

Edek (Edward)Zaidenbaum: Lilly's Jewish boyfriend

Lolek Bitoft: Lilly's Polish boyfriend and son of the Pharmacist in Wloszczowa

Prologue

On a cold and snowy winter day, in 1943, the last transport from the ghetto of Wloszczowa, a small town in the south of Poland, is getting ready to leave. It is transporting the last remaining Jews to the Treblinka death camp. There, on a concrete platform fenced in with barbed wire, German soldiers stand guard, some holding onto fierce attack dogs, exposing their intimidating teeth. With the butts of their rifles, they shoved the frightened people who had just disembarked from the train they had been squeezed in for two days in sealed wagons without any food or water. They are led into a large concrete structure and commanded to undress and get ready to shower. Completely naked, they are told to run into the "cleansing" hall; when it was full, the doors were shut. Among dozens of Jews who were crammed into the sealed chamber I spotted Lilly, my young and beautiful aunt, standing there naked, trying to hide her nakedness with her hands, shivering with cold and fear. Almost complete darkness reigns inside with people pushing, praying, crying and screaming in despair.

After a few minutes a small hatch opens from the ceiling and a single beam of light penetrates. Everybody looks up and watches as a small canister is thrown down into the room. Suddenly a pungent smell rises from the floor and engulfs the room. People grab their throats, choking, coughing and vomiting. They start climbing one onto the other as they try to reach higher levels where there is still some air.

After a few moments, there is complete stillness; no groaning or suffering. Deathly silence takes over.

The sound of creaking hinges is heard and the doors open. Guards wearing masks peek inside and see that there are still some bodies twitching and fluttering as white foam drips from their mouths. The guards quickly move away, allowing the gas to dissipate and evaporate before other prisoners arrive to remove the bodies and move them to the crematorium where they will be burnt. Among those bodies is the body of my aunt Lilly, who was only twenty-seven years old.

I recognized her image from the many pictures that were found in perfect order in her personal album that was hidden by a Polish family. I also felt I knew her from stories that I heard about her from my father - her older brother.

Ever since I saw her image, I began to dream, and the dream haunts me; those frightening recurring images. Nearly always, at the point when her body is thrown into the oven of the crematorium and the metallic sound of the iron door being locked, I wake up sweating with my heart pounding.

I lie awake in bed and think and imagine what those poor souls, who went like lambs to the slaughter, must have experienced. Those were real people, many of whom were from my large and diverse family. Those thoughts provoke anger in me and a strong desire to take revenge. My body aches and refuses to believe that all this really happened.

But I have been there several times, to Majdanek, Treblinka, Auschwitz, Birkenau and Dachau. I saw everything; the barracks, the crematoria, the execution wall, the platform and train tracks. Although seventy years have passed, it seems as if it were yesterday.

Lilly was murdered four years before I was born, and two years before the Second World War ended.

Poland, the small town of Wloszczowa December 25, 1915

Lilly’s birth

Lilly was born a minute after midnight on the 25th December 1915, just as the nearby church bells rang heralding the birth of Jesus. She came into the world like him, as a Jew.

Lilly's family lived in the Polish town of Wloszczowa, southeast of the capital city of Warsaw. They lived in Kilinskiego street number 13. A small white two-story row house, where from the front gate of the house, a narrow paved path led to the main entrance door. In the rear there was an unkempt garden with wooden fences that separated it from the neighbors on both sides.

When Ida's labor began and the contractions became stronger, Jadwiga, the Polish midwife, was called to help prepare for the imminent birth. Several days earlier, Dr. Herman Mirabel, a close family member from Lodz, was summoned to deliver the baby. Wolf, Ida's husband, had insisted that he will be present at the birth. Although Dr. Herman was a dentist, Wolf respected the vast knowledge he had of medicine, since he had studied medicine for several years before specializing in dentistry, and his presence had a calming effect on Wolf.

Ida was no longer a youngster; she was nearly thirty years old and she had given birth to her first-born son Davidek nearly three years ago. Little Davidek was now hiding beside the fireplace on the ground floor, as his uncle Stanislaw was trying to distract him from what was happening on the top floor by playing hide-and-seek with him. Dr. Herman had also overseen the first birth, even though it had taken place in the hospital in Warsaw.

Despite his heavy weight, Wolf displayed an incredible agility running up and down the narrow stairs every few minutes. When he reached the top floor, he stood by the closed door and listened to what was happening. He then ran down to give his brother-in-law Stanislaw a progress report. Just when the church bells began to ring and the Christian world was informed about the birth of Jesus the messiah, the voice of a crying newborn could be heard.

Wolf raced up the stairs. When he reached the bedroom door he stopped for a moment and as a fine Polish gentleman, he first cautiously knocked and asked if he were permitted to enter.

Little Davidek had to wait downstairs for another hour, before being permitted to see his new baby sister. When the door to Ida's room was finally opened, Stanislaw and Davidek went upstairs to see baby Lilly, who was clean and wrapped in a towel, tucked in her mother's arms with an appearance of calmness spread across her beautiful little face.

Jadwiga rushed to place the dirty sheets and towels into a large sack. Ida lay in bed covered by a white sheet to her waist, exhausted, but with a happy smile as she had always wanted a daughter, whom she could call Lilly.

As soon as Ida felt strong enough to walk around, she allowed visitors to come to the house. To accommodate everybody, Wolf had to extend the family dinner table and he placed it against the living room wall. He put out several bottles of Wisniak, vodka, and plates of neatly cut-up kielbasa1 pieces. Into floral ceramic bowls, he placed delicious smelling strudel pastries along with poppy-seed yeast cake that his Polish neighbor Zosia Szawlonska had prepared in advance.

The first to arrive was the battalion commander of the Austro-Hungarian army camped out in Rynek square in the center of the city. He was the commander of the occupying unit who had entered the city a few months earlier without facing any resistance and without a single shot being fired.

The townspeople looked at them with apathy and indifference, while the soldiers chuckled as they looked with curiosity at the Orthodox Jews, wearing long black coats and fur hats, sporting long beards and side locks, on both sides of their faces, that blew in the winter wind. The language they spoke sounded like German, but they could not understand it at all.

Wolf approached the officer, shook his hand as he bowed and said, "Welcome to my home, Herr Kommandant Schoenfeld. What an honor this is."

The officer stomped with his shiny black leather boots, approached Wolf and patted him on his shoulder and replied, "I have come to bestow my blessings upon you on this happy occasion. I thank you for inviting me."

Wolf accompanied the officer to the table, introduced him to the Ida and the baby and poured two glasses of vodka.

"To Lilly," Officer Schoenfeld bellowed. "May she merit a long and happy life." With that, they raised their glasses and poured the contents down their throats.

Wolf had known Officer Schoenfeld, who was a bridge enthusiast, ever since he occupied the town of Wloszczowa and settled there. When he inquired among the residents of the town who played bridge, Wolf, an avid player, made himself known. Every Wednesday evening promptly at six o'clock, Wolf would arrive, on his motorcycle, at the estate of Count Jan Sosnowski. Wolf was the Count's accountant and financial advisor. On his way he would pass by the church and pick up the town's priest, Father Dabrowski, who was an astute and sharp bridge player and who admired Wolf greatly.

Although Wolf was a Jew, he did not feel much sympathy for religion, any religion. He had never been inside a synagogue, did not understand the Yiddish language, and rarely had contact with Orthodox Jews. He was not interested in politics and adopted the popular Polish customs. He would introduce himself as a Pole of Jewish origin. However, he never denied his origin or tried however to hide it in any way.

When the private driver of Count Sosnowski arrived at the house and walked up the stairs alone, Wolf sensed that the Count would not be attending the celebration. Indeed, the Count did not come, but he sent a carved box of painted wood that had a thin silver chain with a clasp in the shape of a heart in it. It neatly fit around the tiny arm of baby Lilly.

Wolf excitedly thanked the driver and handed him a glass of fine vodka with some pieces of kielbasa. There was great mutual respect between the Count and Wolf, a kind of repressed friendship, not the intimate friendship that existed between him and Father Dabrowski.

Then Aunt Eugenia, Ida's sister, arrived with her husband Stanislaw. Ida's fifteen-year-old sister, Emma, arrived with her unmarried sister Roza, with whom she lived. Emma was a voracious reader, a bookworm, and an excellent student, but stubborn and rebellious. When the secular Jewish youth movement was established, she joined without consulting anybody in the family. After several weeks she moved on to a more advanced youth movement, known as Hachalutz, which combined advanced agricultural studies with sports training.

Then Dr. Herman's wife, Aunt Bertha, with her two children Mietek and Irka, arrived, having traveled all the way from Lodz.

Father Dabrowski arrived to convey his good wishes, but stayed for only a few minutes. Although nearly everybody knew of him and about his friendship with Wolf, he did not stay for long, so as not to embarrass the guests with his presence.

As the first guests began to leave, Ida's sister Cesia and brother Muniek arrived. At the same time, their good neighbor Zosia, who was highly pregnant, also arrived. She had been very helpful around the house making sure that Ida had everything she needed.

Everyone wanted to hold baby Lilly who was sleeping in her mother's arms and was oblivious to what was taking place around her.

Dr. Herman offered himself as a waiter. He served everyone with steaming hot tea from the very impressive samovar that Wolf had received from his older brother, when he had visited him in Moscow a few years earlier.

"Is the water hot enough?" Ida asked. Hermann looked at her, smiled and said, "Do you not trust me, dear?"

Ida was concerned because a cholera epidemic was raging in town and had claimed many casualties.

Aunt Eugenia was not at all pleased with the presence of the Austrian officer, and showed great displeasure when he approached her and kissed her hand. He looked at her and spoke in German, but she pretended that she did not understand what he said.

Eugenia moved toward Ida, took Lilly from her hands, and said, "Now you have to play something for us." Ida blushed and tried to get away, but all the guests began to clap, so she had no choice. She took her twelve-string double guitar, sat on a slightly higher chair and began to strum. Her slender fingers began moving quickly and the pleasant sounds of a flamenco rhythm that she had learned from a Gypsy street musician, began to emerge. She had brought the Gypsy home and paid him with hot meals so that he would practice her favorite flamenco melodies with her.

The Austrian officer, who was quite drunk, tried his hand at dancing, while the guests encouraged him with rhythmic applause. Wolf stood behind him with outstretched hands ready to support him in case he stumbled. Suddenly Wolf found himself lying on his back on the floor, while the officer was still dancing and stamping the soles of his boots on the thick carpet that covered the wooden floor.

re.

Ida stopped her playing. Stanislaw and Dr. Hermann dragged Wolf into the bedroom and laid him down and undid his bow tie and belt. Wolf, who suffered from high blood pressure, was periodically in need of leeches to be placed on him in order to suck out his blood to lower his blood pressure.

From the glass jars that stood in the corner of his desk, they removed the hungry leeches and placed them around his neck and arm.

The bewildered guests began to disperse and leave. Thus, on a discordant note, the birthday celebration in honor of Lilly abruptly ended.

A few days later Wolf recovered.

Dressed as usual in his elegant suit, sporting a black bow tie, a walking stick in one hand and a brown leather briefcase in the other, he went to his meetings. Wolf, who had studied law had never practiced as such. While living in Warsaw he applied to, and was hired by, the Ministry of Finance. He specialized in the monitoring of tax payments, and was appointed regional supervisor of the Radom-Kielce district. Since Wloszczowa was only fifty kilometers from Kielce, and that was where Ida's sister Eugenia and her husband Stanislaw Szajkowski and unmarried sister Roza lived, he decided to settle in Wloszczowa. He rented a small house and moved all his belongings from Warsaw.

Wolf's brother-in-law, Stanislaw, was employed by the local authorities as a forester where he worked for several years. He was in charge of the logging and the controlled thinning of the surrounding forests.

He then got a job managing a large saw mill belonging to one of the wealthiest people of Wloszczowa, Rabbi Moses Eisenkott, a strictly observant Jew. Since the local farmers would harass his workers, Rabbi Eisenkott gave Stanislaw the responsibility of dealing with the farmers. Stanislaw was well built, good looking, tall, bright eyed and had straight spiky hair like a hedgehog. He had studied in Polish schools and spoke fluent Polish. However, when it came to speaking to the Polish peasants, he spoke in their language and spiced up his words and threats with every vulgar word imaginable. That was the only language they understood.

Many a time even on very cold days, he would remove his shirt, grab a long ax and chop a tree down singlehanded, all to impress and to scare those who intended to harass the employees of Rabbi Eisenkott.

The murder of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, by a Serbian student, did not shock the Polish press. The incident appeared in a small article and did not arouse much interest. Nobody thought that a local incident that had taken place in Sarajevo would affect the whole of Europe and be the catalyst for the start of the First World War.

When the Austro-Hungarian army invaded Warsaw in early August 1914 and defeated the Russians, the sworn enemy of the Poles, in the eyes of many they were their allies and saviors. When they entered the city of Wloszczowa there was no great resentment against the conquering army. To the contrary, the Jews, who had recently suffered from repeated attacks at the hands of the local farmers, hoped that from now on they would be protected by the occupying battalion stationed in the city.

In March 1917, rumors circulated of unprecedented protests across the Polish-Russian border, as the Russian Czar Nicholas II, had abdicated and appointed a weak government. The Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin, became more and more vocal, until the night of October 24th of that year the Communists overthrew the government and seized power.

On the night of July 16th 1918, the entire Romanov family, including Nicholas II, were executed in Moscow. The Russian bourgeoisie and nobility fled because of the anger of the masses. Among those who managed to escape to Poland with a large portion of their wealth, was a Jewish businessman named Moses Moses Wolowleski. He fled to Poland and reached Warsaw together with his five-year-old son, Adam.

Bolshevik winds blowing from the east

On November 2nd, 1917 Lord Balfour wrote the following official letter to Lord Rothschild, which became known as the Balfour Declaration.

Foreign OfficeNovember 2nd, 1917Dear Lord Rothschild:I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet:His Majesty's Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.Yours,Arthur James Balfour

When the content of the letter was published in the press, the Jewish members of the city administration of Wloszczowa, organized a mass solidarity rally. All kindergartens and Jewish school children, including Hasidic schools and yeshiva students from the villages around came to the assembly. The town square was full of celebrating people. Wolf and his son David were among the participants at the rally. Speeches were made and the atmosphere was festive. The leaders of the Bonds organization were absent, but the rest of the Zionist movements, religious and secular participated.

This was one of the rare occasions when one could see bearded Hasidim embracing secular Jews and greeting them with blessings of thanks for the opportunity given to them by Her Majesty's Government for the return to the Jewish people to their homeland. There were those who came although they did not understand the significance of the announcement. The feeling was that something grand was happening and that perhaps the Messiah had arrived to take them to the land of milk and honey.

Many knew that the goal was to leave their beloved country which had been their homeland for many generations; the country to which they were loyal, their culture, language, customs. They would have to leave all the wealth they had accumulated behind and start a new life elsewhere, in a hostile country, with a harsh climate and a Muslim population who didn’t not want them there.

A few days after the great euphoria, everything calmed down. Life in the town returned to normal and remained relatively quiet. The occupying army had brought in their own administrators, albeit German speaking, and all government institutions, courts and municipal offices re-opened once again. Many street names have been changed and the name of the Rynek (Market Square) was re-named Franz Josef Platz.

On market day, many soldiers came and bought merchandise even from Jewish vendors. The competition among the Polish vendors often led to riots and Rynek Square turned into a battlefield.

Roza and Emma, got along well. Roza was the oldest of the six daughters and one son of Isaac Friedberg, a businessman, whose business had failed and he died a broken man at an early age. He was one of the sons of the well-known Jewish writer Abraham Shalom Friedberg, who died in 1902 and was buried in Warsaw.

After Roza was born to Isaac and Leah, they had Ida and Bertha. When his first wife died, Isaac re-married and had daughters Eugenia and Cesia, son Muniek and youngest daughter Emma. Since Roza remained single, she "adopted" her younger sister Emma, and they lived together in a small apartment.

Once, when Emma returned from the all girls' school where she learned the art of embroidery and weaving, she brought home a thin booklet which she had hidden under her shirt.

Roza noticed that everyday Emma locked herself in her room and hardly came out and she began to suspect something.

One day Roza surprised Emma and entered her room as she was reading the booklet.

"May I know what you are reading?" she asked curiously.

"What difference does it make? Better that you don't know," Emma answered.

"I demand that you tell me," Roza insisted.

"It's the Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels,"Emma replied.

"Do you know that you are taking trash into the house? Do you want us both to wind up in jail?" Roza screamed.

"You have nothing to worry about. The revolution is already here," Emma replied in an authoritative voice of importance.

"What are you talking about? I do not want to hear this nonsense of yours," Roza retorted.

"Did I not tell you that you were better off not knowing what I was reading. You don't want to listen to me," Emma began. "Poland is a nationalistic country, and we must get rid of the nationalism because the proletariat is in a national trance. The proletariat must unite into one nation, but on the condition that they get rid of the bourgeoisie."

Losing her wits, Roza shouted on top of her lungs, "Shut up, I don't want to hear what you're saying. We will all go to jail because of you," and began to attack Emma trying to grab the brochure from her hands.

"A new society will arise. Communism will rule the world where everybody will be equal. There will be no social classes and no religion. Don't you see the progress?" Emma insisted.

Rose grabbed the booklet from Emma's hand and began tearing out pages and chewing on them.

"They may not be found even in the garbage pail," Roza screamed.

Emma did not get excited. She allowed Roza go wild with the booklet as she watched it disappear in her throat.

She stood up, pulled down her big backpack from on top of the closet and began to pack her clothes and belongings.

"What are you doing?" Roza asked.

"I'm packing because I am leaving," Emma answered in a spine-chilling tone.

"Where will you go?" Roza asked as tremors of anxiety could be heard in her voice.

"To mother Russia, where I belong," she replied.

Roza tried to dissuade her and said," You are only seventeen years old. Do you know what can happen to you in Russia being all alone?"

"I am almost eighteen," Emma snapped back. "I know exactly what I am doing. Don't worry about me. I will not write anything to you, so as not to involve you."

Roza approached her, hugged her and said, "I will miss you very much. You are like a daughter to me, even though you are my younger sister."

Emma hugged Roza tightly and cried quietly and said, "I will not say good-bye to everyone. Please give them my love and ask them all for forgiveness. There is a fire burning inside me and I see in communism the future of the world. It will also reach Poland, at which time I will return home to my family."

Roza took a wad of bills that she kept for a rainy day, from a jar that was hidden in an alcove beside the fire place.

With tears in her eyes Roza said, "This is for you, so that you can arrive safely wherever that may be." Emma tried to push her away, but Roza stuffed the money into her coat pocket.

Emma was a physically developed young lady and was very active in sports. The clothes she wore were always a bit too big on her, and she had a masculine walk. She regularly wore a cap made of a coarse fabric that hid her young looking face. She went to an all girls' school, but she did not see her future as a worker in a textile factory. She had other ambitions. She wanted to better the world, as she saw human suffering and human exploitation as the cause of all social ills.

As with the rest of her family members, she also did not attribute much importance to religion. She claimed to all those who would listen to her, that the time has come for the Jews to accept the customs of the Poles, dress like them, speak their language and assimilate with them. There ought not to be any distinction between a Polish Jew and a Polish Catholic. Religion should be considered secondary and unimportant in the eye of the law.

Emma's first attempt to cross the border into Russia failed. Her misfortune came when she was deceived by some Polish fishermen who had promised her to take her across the River Bug. She paid them part of the fee, and then set a place and time where to meet. When she arrived at the appointed time, nobody was there waiting for her. Afraid that the Poles would betray her to the police, she fled and ran to the closest border town. There she got on to a carriage that took her to the county town of Kielce. From Kielce, it took her two more days to finally return home.

When Roza opened the door and saw Emma standing there, they fell into each other's arms and wept uncontrollably. Roza never asked what had happened to her, and Emma considered herself lucky that she was not caught and thrown into jail. Nobody raised the issue again. She went back to her old routine, but never gave up on the idea of communism. She waited for the opportune time to join them.

Emma's attempt to cross the border was a secret she shared only with Roza and it remained unknown to the rest of the family.

Emma, who closely followed the events happening in Russia, began preparing herself once again to run off to Russia. She decided not to go by herself again , and began talking to friends from the secular Jewish youth movement about joining her. She succeeded in convincing two of them.

Fiszel and Wladek both hailed from Wloszczowa. Fiszel was the eldest son of Simon Wasserman, a wealthy leather merchant who had a warehouse near the market and owned a spacious two-story house with a large yard. Simon was an ardent and active Zionist who sent his son, Fiszel, to the Beitar youth movement, and later on to the secular youth movement, where he met Emma.

Wladek hailed from the outskirts of town, where the people lived in wooden shacks. His father, Hirsch, was a pauper, who would clean Rynek square on market days. The stallholders would pay him with a bit of food, and more than once he came home from work empty-handed and his family went to bed with their stomachs grumbling from hunger.

Wladek, who was strong and trained in the youth movements, saw Emma's enthusiasm about communism and it opened a new vision for him. He agreed to leave Poland with her and Fiszel and join the Bolsheviks in Russia.

Fiszel and Wladek, both in their twenties, were not such close friends, although they saw each other at times at the club. Both were fond of Emma who was now barely eighteen years old.

Thus, on November 3rd 1918, while the Austro – Hungarian army was leaving Poland and the day that Poland declared its independence, three youngsters left home. An acquaintance that had a small truck transported them close to the Ukrainian border, where a small boat was waiting for them to transport them to the Russian side.

Emma disappeared in the chaos of the Bolshevik Revolution, and her family never heard from her again.

Lilly was three years old when Emma left, never to return.

Luck Smiles on Cesia

Independence Day celebrations on the third of November 1918 lasted several days. People danced in the streets, taverns were full of people and huge bonfires were lit that spread heat and created a holiday atmosphere in Wloszczowa. Stands placed around the Rynek square, were selling Polish delicacies. Little piglets threaded on skewers were rotating and roasting over hot coals. Groups of Poles stood around waiting for the seller to finish sharpening his knife and to begin slicing juicy pieces of meat. Shotgun fire could be heard from the revelers as they fired into the air, marking the liberation of Poland from the hands of the Austro-Hungarians and Russians. There was great joy in the streets.

At home, Wolf, Ida, Cesia, Eugenia and Roza all sat in an atmosphere of gloom. Roza's eyes were red from crying, as she held the letter Emma had left on the table before leaving home. She read it over and over again, refusing to believe that she would not see her younger sister ever again.

The letter began with the words, To my dear family, and then went on to list each and every family member, including the names of Lilly and Davidek who were three and six years old respectively. No name was omitted.

By the time you read this letter, I will already be far away from you, within the borders of Mother Russia or in a Polish prison (in the event that I am caught). This time I am not alone. Two strong young men, both from Wloszczowa, are accompanying me. Do not worry about me. If the opportunity arises I will send you information about myself without endangering you in any way. Take care of yourselves. I am sure that sooner or later, the communist revolution will come to Poland and we will again be united. I love you all.

Wolf took the letter from Roza's hand and threw it into the fireplace.

"It's dangerous to have this type of letter around the house," Wolf began. "Should any acquaintances or neighbors ask what happened to Emma, tell them that she moved to Warsaw to live with her grandfather Isaac's brother, Ilia Friedberg, who is a famous dentist. This way nobody will suspect that she has just disappeared."

One day, Cesia, Ida’s younger sister, decided to travel to Warsaw to visit her uncle Ilia. That would also afford her the opportunity to see his daughters Mila and Stefania, both of whom she had not seen in a very long time.

After an exhausting trip that took a whole day, she arrived in Warsaw. Her Uncle Ilia was waiting for her at the train station.

Dr. Ilia Frieberg lived in a luxurious apartment in a very prestigious suburb of Warsaw; his dental clinic was adjacent to his apartment. As he was one of the most popular dentists in the city, his clinic was always full of patients standing in line in the waiting room.

Ilia was very fond of Cesia and always worried lest she would remain an old spinster. At every opportunity he encouraged her to try to find a husband. He even tried to persuade her to stay in Warsaw where her chances of finding a husband to her liking were much greater. He was afraid that if she remained in Wloszczowa, having no choice, she would marry a young yeshiva student who had no profession. He did not realize that yeshiva students would not even consider a "shikse" like her.

Two days after her arrival, Uncle Ilia organized a festive dinner at his house, to which he invited Moses Wolowelsky, a wealthy businessman whom he had met at a club to which he belonged. They had in time become close friends. Moses was a rich widower from Moscow who had made most of his money in real estate. At the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution, he had decided to flee to Poland together with his five-year-old son, Adam. Although he was forced to abandon his properties and most of his belongings, he managed to escape with a box full of gold ingots. He bribed the officials at the border to permit him to enter Poland and eventually reached Warsaw. He stayed in a luxury hotel and began buying real estate. He bought two apartment buildings on the prestigious Ogrodowa Street, each with ninety apartments, all of them rented. He then bought a flour mill in the suburb of Praga, and finally bought a villa in Michalin, a summer residence, 30 kilometers from Warsaw.

Cesia, although not so very young any more, was undoubtedly a beautiful woman.At the dinner Ilia introduced Cesia to Moses. She immediately captured his heart. Two days later, as they were walking in Park Lazienki, he proposed to her. A shocked Cesia requested that he allow her some more time so they could get to know each other better. However, Moses did not want to wait and he pressured Cesia for an answer. Within a few weeks they were married. In the spring of 1923 the wedding, a civil one, was held in the Town Hall. It was very low key. Besides the witnesses, it was attended only by Roza, Berta and her husband Herman, Eugenia and her husband Stanislaw, Ida and Wolf and her brother Muniek.

About a year after she was married, Cesia became pregnant. On weekends they lived in Michalin, while during the rest of the week they lived in a large apartment in one of the buildings on Ogrodowa Street in the center of Warsaw.

Ida ,who in 1922 had given birth to her third child ,a son who was named Izio, occasionally visited her sister Cesia, and would bring along Davidek who was the same age as Adam. She would leave Lilly and Izio behind in Wloszczowa, in the care of their Polish neighbor Zosia, who they loved very much.

On January 13, 1925, Cesia gave birth to a son whom they named Jerzy. Moses loved history and especially that of the United States, which he had visited several times on business. He was a great admirer of George Washington and named his son Jerzy, which is the Polish version of George.

Not that long ago, Cesia thought to herself, she was a single young woman, who lived in a small town in the south east of Poland. Although she did not come from a poor home, they were not rich either. Her parents had been Jewish bourgeoisie - Polish, educated and people of standing. Her sister Ida was married to Wolf, a lawyer, whose mother, Pauline, hailed from the well-known Wolfson family. Pauline's brother, Julius Wolfson, was a composer and conductor at the Philharmonic Orchestra of Vienna. He was always traveling between Vienna, Warsaw and Berlin and had been to New York many times. Pauline’s uncle was David Wolfson, one of the founders of the Zionist movement and the deputy to Theodor Herzl, head of the World Zionist Movement.

Cesia herself was the granddaughter of the famous Jewish writer, Abraham Shalom Friedberg who died when she was seven years old. She attended the funeral which was held in Warsaw and listened to the eulogies delivered by many prominent community members including the chief rabbi of Warsaw. She visited his grave site many times. The tombstone was designed by a famous architect

She remained in touch with his daughters. Her aunt, Isabella Grinevskaya, nee Berta Friedberg, was a playwright and novelist and at that time lived in Constantinople. Bertha’s sister ,Luba, lived in Lodz. She was a dentist and was married to a dentist, Herman Mirabel. Her uncle, Ilia Friedberg was also a well-known dentist in Warsaw.

Cesia's head was in the clouds.

Ever since she had married a wealthy man and their son Jerzy was born, she felt on top of the world. At every occasion, Moses gave her gold jewelry decorated with diamonds, mink furs and imported hats from Paris. She had domestic help for cleaning and childcare, as well as a chauffeur who drove her everywhere. She loved all the wealth, loved the nightlife of Warsaw and disliked visiting Wloszczowa. Most of all she resented anything remotely connected to Judaism and religion.

When Jerzy was born, Cesia decided not to circumcise him. Moses begged and pleaded with her, but to no avail. She remained adamant. She claimed that circumcision was an act of barbarism and in their modern times it was unnecessary to mutilate body parts.

"If you claim that God created man why cut off the tip of his penis? What happened? Did He make a mistake with his creation," she asked Moses. At such a weighty question, Moses had no answer..

After she was widowed Paulina Wolfson, grandmother of Lilly, Davidek and Izio, moved in with her brother Julius in Vienna. But she could not get used to life in the big city, and after two years she decided to move in with her son Wolf in Wloszczowa.

Life in Wloszczowa

Life in the city of Wloszczowa was quite relaxed. The neighborly relations with the Catholic inhabitants were good, with the exception of a few disputes among the peasants, brought about because of competition. On market days, the Jewish buyers preferred to buy from Jewish peddlers, both because of the rabbinic seal of approval and due to competitive prices. The Catholic peasants, whose products were better and fresher, got very upset and viewed the Jewish buying practices as a boycott against them. All in all, however, friendly relations existed among the residents in the city, and there were even a few cases of mixed marriages.

The Jews in the surrounding villages were mostly orthodox who spoke mainly Yiddish and hardly any Polish. They looked different from the rest of the population, sporting beards and side curls and always wearing long black coats and black hats. Poverty was rampant, as each family had many children. Instead of schools, the children were sent to a private house where a rabbi taught them Torah. These were not like government schools, where children studied history, math, science, Polish and even French as a second language.

When they came from the outlying "shtetel" (small Jewish villages established around a large city) to Wloszczowa with their horse or mule-drawn cart, the Jews were often the recipients of stones that the Catholic children threw at them. Insults and curses were also a regular occurrence; at times they did not even understand the insults screamed at them.

The Jews who lived in the town who were not religious distanced themselves from the orthodox Jews and treated them disrespectfully. Many despised them outright .They saw themselves as Poles of the Mosaic faith, and not as Jews living in Poland.

Every morning, Wolf would leave his house, neatly and elegantly dressed in a plaid jacket, bow tie, and white cotton trousers with a leather briefcase.

Since the cost of living in Wloszczowa was rather high, his government salary was barely enough to cover his expenses, so he took upon himself additional work. He was hired as a financial advisor to Count Jan Sosnowski, a rich Polish nobleman who lived on a large estate approximately thirty kilometers away in the town of Maluszyn. The count was a hearty man who loved women, playing cards and drinking. In Wolf he found two things; a consultant who helped him streamline his business and make it more profitable and a companion for a good game of bridge.

Along with his job, Wolf received a car to travel to work. It was a Fiat 520 Cabriolet with gas lamps. On the weekends he would ride around the neighborhood on his Ariel model English motorcycle that he purchased for four thousand zloty.

Thursday of every week was market day. The peddlers would arrive at the crack of dawn with their goods in carts drawn by horses or donkeys and begin setting up their stalls in the Rynek Square marketplace. Some even harnessed themselves to smaller wagons with two wooden wheels, while another person stood in the back and pushed. Even on rainy days, when they were exposed to storms that struck the region, they could not give up, because of the need to bring money home to support the family.

One morning, as every morning, Ida took Davidek, who had just turned twelve, to school. That day Lilly decided she did not want to go to school because she claimed that she was bored. She already knew how to read and write, for she studied the material from her brother's books. Izio, who had a cold, stayed home with his grandmother.

Since that day was market day, Ida and her daughter Lilly walked from home to the square as the distance was not that great. Ida allowed Lilly to run ahead and back again, as she wanted her to release some energy and calm down a bit.

As they got closer to the market the sight of the bearded peddlers wearing long black costs frightened Lilly and she clung tightly to her mother.

"Mamushka," she asked, "Who are these people?"

"Orthodox Jews from the surrounding areas," Ida answered.

"We are also Jews," she stated. "Why do they look different?"

"They are religious Jews who belong the Hasidic movement, while we are not religious and belong to a different movement," Ida replied.

"Why do they speak German and not Polish?" Lilly asked.

"They are speaking Yiddish, the language of the Eastern European Jews," her mother replied.

"Why do we do not speak Yiddish?" Lilly asked inquisitively.

Ida tried to give her nine-year-old daughter an answer that she could understand. "We are more modern and open-minded Jews who believe that we must move forward and live in Poland, like Poles. We are first Poles and then Jews."

"Mamushka, I am so glad that we do not belong to the Hasidic movement," Lilly said while hugging her mother.

"They are good, hard-working people with large families. We must respect all human beings, regardless of religion or ethnic origin," Ida replied.

Little Lilly did not answer. She stared at the children who were approximately the same age as she was, working very hard helping their parents. Some carried heavy sacks on their backs while some stood on boxes, loudly announcing the nature of their goods in order to arouse the curiosity of the buyers and attract them to their stand. They wore old patched clothes, worn-out shoes and large caps on their heads.

After buying some potatoes and carrots, Ida finally arrived at the butcher's stand to buy a chicken. The butcher took out a fat chicken from the coop, showed it to her and waited for her agreement. When Ida nodded her head in agreement, the butcher took the chicken by its neck and swung it in a forward motion. With its head dangling, the chicken continued to shriek and flap its wings. After a few minutes the chicken died and the butcher's wife immediately began plucking its feathers.

"I will not eat this chicken nor will I eat the soup that it was cooked in," Lilly announced in an angry voice.

Ida looked at her daughter and said, "So you will remain hungry," she said.

She then added, "I cannot buy at the Jewish butcher, indeed his whole chickens are already dead and headless, however they are salted and father may not eat any salt. Also, his chickens may not be fresh."

"Nevertheless, I will not eat the chicken after I saw it was killed ," Lilly responded.

After Ida took the chicken wrapped in newspaper and put it into her shopping bag, the two started walking home.

"I must go into Bitoft's pharmacy for a minute to get something," Ida said and crossed Rynek Square, with Lilly reluctantly in tow.

Bitoft, who was tall, solidly built with a black mustache adorning his face, stood behind the counter, looked at her and asked, "How can I help you madam?"

I need cough medicine. Izio is constantly coughing. I am sure that he has bronchitis," Ida said to him.

How old is he?" the pharmacist asked.

"Two years old," she replied.

"Wait a few minutes and I will prepare an appropriate syrup," he said as he walked off into his laboratory.

Ida and Lilly sat on the bench waiting. A cute boy, neatly dressed with golden curls and a smiling face sat next to them. The boy looked at Lilly and did not take his eyes off her.

"Why are you looking at me all the time?" she protested.

The boy's face reddened as he looked down to the floor. He did not open his mouth.

Ida, who felt his embarrassment tried to straighten things out.

"Why are you hurting the boy, he did nothing to offend you?" she scolded Lilly.

"Never mind," the boy said "She did not hurt me."

"Ho, ho, he knows how to talk," Lilly teased him.

Ida once again scolded Lilly and shoved her to shut up.

"Are you waiting for somebody?" Ida asked the boy.

"No, I am the son of a pharmacist, and I am waiting for my father to close the pharmacy and go home," he answered.

"What is your name?" she asked.

"Lolek," he replied. "That is what everybody calls me."

"How old are you," Ida inquired.

"Twelve," he replied shyly.

Lilly listened attentively to the conversation, but did not interfere. She let her mother do the investigating.

"You are the same age as my Davidek. You might want to come play with him sometime," she said to him.

While Ida was explaining to Lolek where they lived, the pharmacist entered.

"I see you've introduced yourself to the ladies. You do not waste any time," he said with a smile.

Lolek blushed and looked down.

"He is very shy," Bitoft said winking at Lilly.

Lilly remained silent, but occasionally stole a glance at Lolek; whether out of curiosity, or to embarrass him more, only she knew. She relished seeing him embarrassed and red-faced.