9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

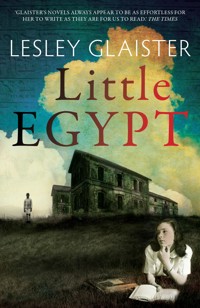

Winner 2014 Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize Longlisted: International Dublin Literary Award 2016 Sunday Herald Book of the Year 2014 Elderly, Egypt-mad twins Isis and Osiris find their neglected English lives disturbed to catastrophic effect by the arrival of American Anarchist, Spike New from Lesley Glaister, winner of the Somerset Maugham, Betty Trask and Yorkshire Post Author of the Year prizes 'This tale of imprisonment and neglect explores our passion for nostalgia, with hints of Dodie Smith's darker side. An excellent read that pulls at the heart as well as the head.' —Victoria Clark, The Lady 'Eerily atmospheric Little Egypt, made me shudder; certain passages were read through half-closed eyes, the way you watch grisly scenes in a film — desperate to know what happens, but not wanting to disturbing images imprinted on your mind.' —Rosemary Goring, The Herald Little Egypt was once a well-to-do country house in the north of England. Now it's derelict and trapped on a small island of land between a railway, a dual carriageway and a superstore, and although it looks deserted it isn't. Nonagenarian twins, Isis and Osiris, still live in the home they were born in, and from which in the 1920s their obsessive Egyptologist parents left them to search for the fabled tomb of Herihor – a search from which they never returned. Isis and Osiris have stayed in the house, guarding a terrible secret, for all their long lives until chance meeting between Isis and young American anarchist Spike, sparks an unlikely friendship and proves a catalyst for change. 'I was gripped by the story from start to finish, finding it a perturbing, poignant and, in places, a darkly humorous read.' —Amazon.co.uk This enormously accomplished novel took twenty years to come to fruition: it is well worth the wait — buy your copy now.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Little Egypt

Little Egypt was once a well-to-do country house in the north of England. Now it’s derelict and trapped on a small island of land between a railway, a dual carriageway and a superstore, and although it looks deserted it isn’t. Nonagenarian twins, Isis and Osiris, still live in the home they were born in, and from which in the 1920s their obsessive Egyptologist parents left them to search for the fabled tomb of Herihor – a search from which they never returned. Isis and Osiris have stayed in the house, guarding a terrible secret, for all their long lives until chance meeting between Isis and young American anarchist Spike, sparks an unlikely friendship and proves a catalyst for change.

Praise for Lesley Glaister

“Pick almost any paragraph on any page in any of Lesley Glaister’s great fat pile of nine novels and you’ll spot a combination of words snazzy enough to make your heart sing. ” —Julie Myerson The Guardian

“Crime writing of the highest order, creepy ... with satisfying fits of the shivers.” Sunday Times

“Glaister’s rounded gift is to show life as it really is.” Independent on Sunday

“Glaister has the the uncomfortable knack of putting her finger on things we most fear, of exposing the darkness within.” Independent on Sunday

“Glaister’s novels always appear to be as effortless for her to write as they for us to read.” The Times

Little Egypt

LESLEY GLAISTERis the prize-winning author of twelve novels, most recently,Chosen. Her stories have been anthologised and broadcast on Radio 4. She has written drama for radio and stage. Lesley is a Fellow of the RSL, teaches creative writing at the University of St Andrews and lives in Edinburgh.

By the same author

NOVELS

Chosen(Tindal Street Press 2010)

Losing It(Sandstone Press 2007)

Nina Todd Has Gone(Bloomsbury 2007)

As Far As You Can Go(Bloomsbury 2004)

Now You See Me(Bloomsbury 2001)

Sheer Blue Bliss(Bloomsbury1999)

Easy Peasy(Bloomsbury 1998)

The Private Parts of Women(Bloomsbury 1996)

Partial Eclipse(Hamish Hamilton 1994)

Limestone and Clay(Secker and Warburg 1993)

Digging to Australia(Secker and Warburg 1992)

Trick or Treat(Secker and Warburg 1990)

Honour Thy Father(Secker and Warburg 1990)

ANTHOLOGIES(as editor)

Are You She?(Tindal Street Press 2004)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Lesley Glaister, 2014

The right of Lesley Glaister to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2014

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 84471 997 6 electronic

For Andrew, once again

Contents

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

PART TWO

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

PART THREE

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PART ONE

SPIKE’S A THINstreak of a boy, American, with silver studs in his face and ears, pale matted snakes of hair, and a distinct whiff of the vegetable about him. He hitchhikes when he needs to travel, or else he walks. He doesn’t believe in money– marvellous!

We met when he sprang from a skip and landed right in front of me in a tumble of rolling oranges. I screeched and clutched my trolley handle, frightened half to death. He was all solicitation and apology – charm, I’d go as far as to say. We were in the service area behind the supermarket and I’d caught him ‘dumpster diving’.

U-Save throws out huge quantities of perfectly good food just because it’s out of date. A sinful waste and shame, I say, and have said, but do they take heed? Once I’d regained my composure, Spike showed me his haul and offered me a caramel doughnut – delightful. And then he climbed back into the skip and called things out:

‘Carrots? Hummus? Tiramisu?’ and if I said yes he passed them to me and I added them to my trolley. I’ve seen him regularly since then and the same has happened, which does save money, but really the fun is in the sport of it, don’t you know? If I could climb and spring about like Spike I’d do it myself. The beauty of it is that you never know what’s coming next. I’ve been introduced to all sorts of new delights that way: panacotta, globe artichokes, sushi, chicken satay on most useful pointed skewers.

Spikebecameafriendtome–likeanangel,youmightsay–anditwasSpikewhosetmefree.

WeweresittingonadoorstepintheserviceareasharingatubofKalamataolives.(Notthemostsalubriousplace.Heretheykeepthebinsandskipsandbalesofflattenedboxes.Herethedualcarriagewayroarsaboveyouandoccasionallyahubcaporpapercoffeecuporstripofrubbertyrefliesdown.Herestraycatsyowlandprowl–there’splentyofvermintokeepthemfed.Andheretoo,thesmokersamongtheU-Savestaffemergetopuffontheircigarettes.I’vespottedI’mDoreenhowmayIhelpyou?,thesourestfacedpersonI’veevermet,puffingawaythere.SeeingmewithSpikecausedherorange-pencilledeyebrowstoshootintoherhairline.Mostgratifying.)

ItwasalateSeptemberday,stillquitewarm,andI’drolledupmytrouserlegstosunmyshins–flakyandcrinkledandmappedwithveins.Howeverdidtheygetlikethat?EachtimehefinishedanoliveSpikeejectedthestoneforcefullyfrombetweenhislips,aimingforanemptybeer-tin,butovershooting.Itoldhimhewasblowingtoohard;hedemonstratedthatifheblewmoresoftlythestonesimplydroppedontohislegs.‘Well,movethetinfurtherawaythen,dear,’Isuggested,buthemerelyfrownedanddesistedfromhisgame.

Weturnedtothesubjectofdreams–inthesenseofambition.HisIfoundgrandbutdisappointinglyvague:peace,love,equality,andsoon.Visionsoftheworldasitcouldbe.AshewaxedlyricalIwatchedthenervousfidgetofhishands–fingersyoungandstraightbutstainedfromsmoking,painfullybittennails.

Whentheolivesweregone,herolledhimselfacigarette.‘What’syourdreamthen,Sisi?’

(YouseehowIreversemyname?Howmuchmorecomfortableit’smade,bysuchasimpleflip.)

‘To leave,’ I said, nodding towards my home.

‘And go where?’

‘Sunset Lodge. Once I’ve sold up.’

He snorted his derision, but I indulged myself once more in describing the luxury I’d seen in the brochures: reclining armchairs, vast televisions, tempting menus, alternative therapists, a dedicated ‘friend’, parties, seasonal entertainment and a 3-star suite for visitors.

Spike ground out his cigarette and fiddled with the packet of tobacco. ‘Don’t give in to the fuckers now,’ he said.

‘You asked my dream,’ I pointed out.

We sat in a silence that almost approached the prickly for a while, until he broke it.

‘They still hassling you?’

I shook my head, which was a lie. Stephen, the latest of the developers’ representatives, waits for me twice a week in the U-Save café where I go each morning for my coffee. I conduct all my business in the café rather than let anyone into the house. (Osi would go berserk at such an invasion.) The U-Save Consortium propose to buy Little Egypt – the last remnant of the family property – to raze to the ground and erect what they call a ‘mega-homestore’ and it’s Stephen’s task to win me over.

From the scattered litter, Spike picked up a glossy leaflet advertising this week’s special offers and skimmed it, scoffing. ‘Thirty-six fishy nuggets – buy two get one free – that’s 108 fishy nuggets. The oceans will be fished-out before they’re finished.’

‘And think of all those fish without their nuggets!’ I jested, but he didn’t laugh.

‘What if,’ I said, ‘now don’t go getting on your high horse, dear, but what if a persondidwant to sell a property to someone like, say, U-Save.’

‘Then they’d want their fucking heads examined.’

He moved to a crouch as if about to spring away, but I caught his arm. ‘But what if, for instance, there was something there, something hidden that got uncovered, dug up, say, during the building work?’

He cocked his head at me and squinted. ‘Like Roman ruins and stuff?’

‘Mmm,’ I said, ‘or a corpse, something in that line?’

There was a chink of silver against tooth as he puffed out his lip. ‘Huh, they’d cover it up and you’d never know. Think they’d let anything get in the way of profit?’

Though he was not to know it, these were the magic words that freed me. It was a thought quite new, a revelation. Ever since . . . well for all the years, all these years I’ve supposed that we could never leave, that onceitwas discovered we’d go to prison; Osi, certainly, and perhaps me, too. That’s what Victor believed and left me believing.

I needed to be back home to test the thought. To be alone. If Spike was right, then we could sell and go. Could it really be so? But what of Osi? I flailed about until Spike hauled me to my feet. (My knees are really dreadful, the left in particular. You can get new ones, I hear, though not, so far, at U-Save.)

‘You really think so?’ I asked him.

‘I fucking know so,’ said he.

1

ISIS WANDERED INTOher parents’ bedroom, stretched out on the stripped, stained mattress and stared at the ceiling. She could hear a faint stipple of birdsong from outside and Mary banging round the house with her broom – she was always in a temper when Evelyn and Arthur left, till she got things ship-shape. Apart from that it was quiet, except for the usual creaking and settling of the house, as if it too breathed and shifted into another mood with the departure.

From where Isis lay, the wardrobe mirror reflected only a dull blue swatch of cloud. Crushed in behind it were all the gowns and frocks that Evelyn shunned, preferring trousers – often Arthur’s own. When she was small, Isis had sometimes crept in to watch her parents dress. They hadn’t cared and went on just as if she wasn’t there at all. As they’d talked – usually about bloody Egypt – Arthur would stride about, hair stamped across his chest like two grubby footprints, thing jiggling and sometimes jabbing out like a fried sausage. Evelyn’s bosoms were like empty socks, her belly hair a puff of mould. The hard muscles in her long shins reminded Isis of the fetlocks of a horse.

Sometimes Isis pictured her mother as a horse, of the thin haughty variety, and Arthur as a big whiskery dog, trotting obediently at her heels.

They had left in high spirits, convinced more than ever thatthistime, after all the years, all the false trails, all the disappointments, they would find the tomb of Herihor. Evelyn said she felt it in her bones, and Arthur always expressed great faith in her bones. Besides, they had a new guide now, a Mr Abdullah, a topping fellow who really knew his onions.

Their leave-taking had been the usual kerfuffle of luggage and lists and last minute panics, the scrunching of wheels on gravel – and swearing this time, when Arthur broke the tread of the third stair while lugging down a trunk. And then the quiet. Only now a trapped fly began to buzz and bat itself against the window and Isis roused herself to let the poor thing out.

She paused to finger the ornaments on the sill – a shiny black scarab, its base covered in minute columns of hieroglyphs; an ankh of lapis lazuli, and her favourite, Bastet, a cat-headed woman, gold inlaid with turquoise and lapis and carnelian. This last really belonged in the British Museum in Arthur’s opinion, but these were Evelyn’s special treasures.

Once the house had been full of Grandpa’s collection of Egyptian statues and ornaments, even an enormous gilded mummy case at the turn of the stairs, but over the years Evelyn and Arthur had sold almost anything of value to raise money for their quest.

Snarling through the quiet came the sound of an engine and Isis peered out of the window in time to see the drawing up of a low, bright yellow motorcar. Once it had stopped, the figure inside, like a gigantic insect in hat and goggles, sat motionless staring up at Little Egypt.

‘It’s Uncle Victor!’ Isis cried as she pelted down the stairs.

For days, Victor, Evelyn’s twin, had been expected back from the nursing home, where he’d been ever since the war. He was still unfolding himself from the motor as Isis launched herself at him, rubbing her face against the stiff twill of his jacket, ‘Oh I’m so glad,’ she said, ‘so, so glad.’

‘Steady on,’ he said. ‘By God Icy! You’ve grown!’

‘‘Well we haven’t seen you foryears!’ She stepped back from him.Heseemed smaller than she remembered and rather old and stooped. ‘We’d almost given up on you,’ she added.

He took off the goggles and helmet and tilted back his head. ‘Good to see the old place again,’ he said. ‘Didn’t always think I would.’ He blinked. ‘Where is everyone?’

‘They’ve only just gone,’ Isis said, ‘literally. This morning. Evelyn hated to go without seeing you – but they had to catch their boat.’

‘But she wrote they’d be here till the 27th.’

‘That was the day before yesterday,’ Isis said. ‘Ourbirthday, we’re thirteen now,’ she reminded him.

Before the war, when they were small, Victor had never forgotten the twins’ birthday, always sending something silly and expensive – and nothing to do with Egypt. As the only other person in the family who wasn’t obsessed by Ancient Egypt, Victor was her ally.

‘Blast,’ Victor said in a dwindling voice. ‘Not much of a hero’s welcome then.’

There was a pause and Isis shifted awkwardly, wondering what to say to this man who looked so different now, and so cast down. The lines on his brow and around his eyes were sharp as knife cuts and his skin was grainy grey.

‘What a lovely motor,’ she offered and it was the right thing, for Victor brightened and patted the bonnet as if it was a horse.

‘Yes. Bugatti. Quite a stunner, eh?’

The interior was upholstered in pale lemon leather and the dashboard was a glamorous glossy wood, intricate with complex whorls of grain. ‘Walnut,’ he said. ‘Pigskin. 16-valve engine.’

‘It’s beautiful.’ She stooped to sniff the leather interior. ‘It smells of money.’

‘Dear little Icy.’ Victor reached out to give her a proper hug. ‘Thirteen,’ he said. ‘I don’t believe it.’ Squashed against his chest, she saw the two of them reflected, in grotesque distortion, by the curve and shine of chrome, and below her ribcage felt a pang, a qualm, and pulled herself away.

Mary came out drying her hands. The sunshine lit up her fair curls and she was smiling. ‘Welcome back,’ she said. ‘You’ve missed Captain and Mrs Spurling. Will you be staying? Only I’m not set up for visitors what with the laundering and them only just gone.’

‘You’re looking well, Mary,’ he said. ‘Does a chap good to see those dimples again.’

Blushing, Mary dipped her head. ‘I’m tolerable. It’s only soup. I expect I can eke it out and we’ve got a bit of ham.’ She slid Isis a look. ‘You can help by laying the table, Miss.’

‘I’ve only just had the tablecloth off,’ Mary grumbled. ‘If I’d known I could of stretched it for another day. He’ll have to make do with second best.’

‘I don’t s’pose he gives a fig.’ Isis took an embroidered cloth from the sideboard and, together with Mary, flapped it over the table.

‘And I had that ham lined up for your tea,’ Mary said, straightening the cloth.

‘But don’t you think it’s nice to see someone else?’ Isis said. ‘And hewasnearly killed, you know.’

Mary nodded and went out and Isis wished she could bite her tongue off. Mary had been married briefly to a Gordon Jefferson. They’d tied the knot in July 1914 before he went off to the front. They’d had one weekend together in Hastings, and then he’d sailed off and got himself shot at the Marne. There was a photograph of the wedding day beside her bed, Mary with a smaller, sharper face clutching the arm of Gordon Jefferson: short, uniformed, bespectacled and stern. Mary still wore the ring, a band of gold, thin as wire, embedded in the work-worn puffiness of her wedding finger.

After she’d washed her hands and combed her hair in readiness for lunch, Isis found Victor standing in the hall, a blank look in his eyes. She paused on the stairs to watch him; he stood as if lost, hands hanging limply at his sides, mouth a little open as if he was stupid, which he most certainly was not.

‘You’ll never guess what we got for our birthday,’ she said extra brightly, bounding down to take his arm.

Victor flinched.

‘Come and see.’ Isis pulled him towards the drawing room. She flung open the door to reveal a cage dangling from a stand and inside it, two bright budgerigars – one blue, one green.

‘What beauties,’ Victor said. ‘Bit lost in here though, eh?’

The drawing room was only used when Evelyn and Arthur were home and Mary had already swathed all the furniture in dustsheets so that the poor creatures were surrounded by nothing but hulking white shrouds.

Isis made kissy noises through the bars and the birds moved away from her with disconcerted chitters and huddled together in a puff of feathers. ‘I hate to see birds in a cage though,’ she said. ‘You’ll never guess what Osi’s gone and called them.’

‘Something Egyptian at a wild stab?’

‘RamesesandNefertari,’ Isis said. ‘Have you ever heard anything more ridiculous?’

‘Youcould call them something else,’ Victor pointed out. ‘They’re hardly going to know the difference.’

‘Mary was livid,’ Isis told him, and mimicking Mary’s voice: ‘What we need’s a new tutor for the twins, someone else to help about the house, a lad to help George in the garden and what do they come up with? A couple of blasted budgies!’

‘Fair point,’ Victor said.

‘Thing is, Uncle Victor . . .’ Isis took his arm again. She didn’t know how to put it, not quite. ‘I worry that Osi . . . that he might . . .getthem.’

Victor frowned. ‘Don’t catch your drift.’

But Isis stopped. One of the budgies and then the other began to cheep, hard chips of glassy noise that rattled against her teeth.

‘Lunch,’ called Mary.

‘Coming,’ Isis yelled back, sending the birds into a frenzy.

She knew she should not worry Victor. Anyway, she had a plan to keep the budgies safe.

At the table, Isis noticed how the spoon shook in Victor’s hand, and as he moved his head, the silk cravat slipped down to reveal a scar, like a livid bacon rasher sizzled to the side of his neck. Dizzied, she put down her spoon. The soup was too thin with the water Mary had added to make it stretch. Peas and cubes of carrot floated on the surface. It was a grudging soup – you could always tell Mary’s mood from the way her food came out.

Victor was trying to have a conversation with Osi. ‘Been out and about?’ he said.

Slurping, Osi shook his head.

‘Have a fine time when the folks were home?’

Osi nodded eagerly and opened his mouth to tell him all about Herihor, but Victor held up his hand and grinned at Isis, almost like his old self for a moment. ‘No Egypt over lunch, if you don’t mind old chap?’

‘Hear, hear,’ said Isis.

Osi scowled at her. ‘Have you got your medal with you?’ he asked Victor. ‘Why aren’t you wearing it?’

‘Prefer to leave all that behind me.’

Isis saw that the tablecloth was jumping where he sat. He saw her looking. ‘My bally leg,’ he said, a note of panic in his voice. ‘It jerks and jumps, I can’t . . .’ He was leaning on it and pressing with all his weight.

‘It’s all right,’ Isis said. ‘Have a slice of ham, Cleo’s having kittens, perhaps you’d like one? There’s dates in the pantry, Mary makes a lovely date and walnut loaf but she says there’s enough dates there to last us till judgement day . . .’

Victor snorted dryly. ‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘No need to gabble.’ But he continued to press down on his leg and pushed his soup aside. He said nothing more and they sat in silence except for Osi’s terrible slurping.

‘Don’t take any notice of me,’ Victor said at last. ‘Didn’t mean to be so sharp.’

‘It’s quite all right! After luncheon perhaps we could go for a walk? Or perhaps a drive? It’s a lovely motor Osi, you should go and look.’

Mary came in, pushing the door with her hip and carrying a bowl and jug. ‘I’ve resurrected a bit of stewed apple for you, and there’s cream,’ she said. ‘And I expect you’d like some coffee.’

‘And a spot of brandy,’ Victor added.

‘Verygood,Sir.’ThedoorbangedalittletooemphaticallyasshewentoutandIsisdartedalookatVictortoseeifheminded,andsawthathiseyeshadgonelostagain,andcloudy.

‘It seems unfair of Evelyn not to wait and see me,’ he said. ‘It was an arrangement.’ His leg began jumping again.

‘They’d booked their passage,’ Isis said. ‘Will you take some apples? And she really was upset to miss you.’

‘Nothing’s as important as their blessed expedition though,’ said Victor.

‘No,’ agreed Isis. ‘Never.’

Osi pulled a gruesome face at her. He was eating with his mouth open as usual and she saw the churn of apples on his tongue. ‘Don’t be so putrid,’ she said.

‘Don’t be so stupid then.’

‘I’d rather be stupid than putrid and anyway I’m neither.’

‘Are.’

‘Not.’ This was unspeakably childish but Isis could not help it. ‘You bloody idiot,’ she said.

‘Now then.’ Victor’s face had gone ghastly grey. He picked up a spoon but it dropped from his fingers and clattered to the floor. He bent to retrieve it but couldn’t reach. He was half under the table, contorted, arm stretched out towards the spoon, panting with frustrated exertion – as if it mattered!

When she bobbed beneath the edge of the tablecloth to retrieve it for him, Isis saw how his leg was jumping and caught the awful frightened tang of his sweat. ‘Forget the blasted spoon,’ she said as she emerged. Her heart flowed out to him, this ruined man, her uncle. ‘Oh Victor I’m so sorry about your neck,’ she blurted. ‘About your leg, poor Victor.’

He gulped, jaw twitching, his whole being trembling with the effort of control, but it was too much. Something in him broke apart and he began to shake. Tears spurted shockingly from his eyes and Isis darted a panicked look at Osi, but he was concentrating on spooning up his apple.

‘Osi!Wake up youfool!’ she shouted.

Victor began to jerk all over now as if he was having a fit.

‘Mary!’ Isis yelled. ‘Mary!’ and she ran towards the kitchen where she collided with Mary who was carrying a coffee tray.

‘Lord above, what’s got into you!’

‘Quick. Victor’s gone berserk.’ Isis took the tray so that Mary could hurry.

‘Mr Carlton,’ Mary said, having to shout above the noise he was making now, a frightful, inhuman yowling. ‘CaptainCarlton. You’re upsetting the twins.’

She got hold of one of his hands and when she got no response, his shoulders. ‘Captain Carlton!’ She shook him until he met her eyes, his all red and flinching. ‘Come now,’ Mary said. ‘Come to the kitchen with me and we’ll see if we can’t get you calmed down.’ Victor was gasping as if he couldn’t get his breath, but he consented to go with Mary and she flicked a look of alarm at Isis as she led him out.

‘Osi!’ Isis went and shook him.

‘Not my fault,’ he said, staring at his empty bowl.

‘No of course not but . . .’Sometimes I could kill you, she thought. ‘How can you just carry on eating? Don’t youcare?’

‘Finished now,’ he said, got up and left the room.

2

LATER, ISIS CREPTalong the corridor to listen at the door of the Blue Room where Mary had settled Victor for a rest, but there was nothing to hear and she went down to the kitchen.

‘Is he staying the night?’ she asked.

Mary was whipping butter and sugar together as if she was punishing it. ‘Can’t send him off in that state, can we?’

‘You making a cake?’

‘He’ll have to have something for his tea.’

‘What kind?’

‘Guess. What’s he doing visiting just when they’ve gone? That’s what I want to know, and if you ask me he’s in no fit state to be out and about.’

‘Date loaf?’

Mary harrumphed.

‘It’s my fault,’ Isis said.

‘You can break a couple of eggs for me,’ Mary said. ‘Your fault? How do you make that out?’

Isis picked up an egg and tapped it on the side of a basin.

‘Harder than that.’ Mary took the egg from her hand and gave it a sharp crack so that it split obediently, its contents slithering into the bowl. ‘And don’t be daft. It’s the war that sent him, not you!’

Isis went back upstairs and listened outside the Blue Room. In hospital Victor had had treatment with electric shocks, but now he only needed to take pills when he had an episode. Mary had made him dose himself and he was sleeping it off and mustn’t be disturbed.

IsiswanderedalongtothenurserydoorandtherewasOsiwithhisbooks.Hedidn’tevenlookup.Imightaswellbeaghost,shethought,andimaginedskimmingovertheworncarpetsandthecreakyfloorboards.Theremustbeghostshere,ofthepeoplewho’dlivedinthehousebefore–maybeofpeoplewholivedherebeforethehousewasevenbuilt–buttheywerediscreetghostsandneverbotheredanyone.

Little Egypt was miles from anywhere – ten from the nearest village. Isis dimly remembered when they used to go there – the grocer’s, the church, a pub, stocks on the village green where people had been pelted with rotten vegetables in the olden days. But now that Evelyn and Arthur were so set on their mission they were always away and the outings had stopped. Mary, left in charge, didn’t allow the twins to stray from the grounds of Little Egypt where she could keep her eye on them. A good school was too expensive and Evelyn wouldn’t dream of letting them be educated with common children. And even the last tutor – a straggly, limping French man, grandly called Monsieur de Blanc – had gone away last year after a row about his pay. Arthur had promised, next time he was home, to hire another tutor. Once they found Herihor, they would be rich, of course, and able to send Isis to the best school in the country. She wasn’t so sure how Osi would get on. Maybe a school would turn him normal?

In her parents’ room it was cold, the sun had gone round to the other side of the house and the papyrus scrolls on the walls, with their men and animals and gods, gave her the creeps. She opened the wardrobe and sniffed Evelyn’s most glamorous dress: green chiffon, sewn with thousands of sequins. The fabric under the arms was whitened with sweat and the sequins were cold as fish scales against her cheek.

She had only one memory of Evelyn in the dress. When Grandpa died it turned out that he’d left Little Egypt to Evelyn, and Berrydale, thirty miles away, to Uncle Victor. Evelyn had been livid because Berrydale was worth more and she needed funds for her expedition, while Victor was bound to fritter his inheritance away.

To raise money for the excavation, she’d sold most of Grandpa’s precious collection of paintings – he was still whirling in his grave according to Mary – and held a ball before they left. Four-year-old Isis and Osiris had been dressed up as their namesakes in long white robes with black kohl caked around their eyes and great tall head-dresses, to be cooed at by all the ladies and gentlemen. Evelyn, the horse, had paced about in the slithery frock, smoking and neighing with Arthur panting faithfully at her heels.

Despite a stab of disloyalty, Isis grinned. If only she could draw, what a funny picture it would make. And after all, Egyptian gods could be people or animals, so why not her parents? She shut the wardrobe and wandered back to her bedroom where she found Cleo crouching on a fallen dressing gown, tail lashing from side to side, quietly yowling.

Cleo was forever having kittens, which vanished overnight. Mary used to claim that she’d sent them by coach to a stray cats’ home, which, at first, Isis had believed, until early one morning she’d found a wet and heavy sack outside the kitchen door.

Years ago, and it still made Isis sicken to remember, she’d discovered Osi with a litter of dead kittens in the nursery. The tiny creatures, all hard and stiff, their tabby fur dried into spikes, had been lined up on the floor as if for some kind of ritual, and his eyes had been bright, cheeks rosy with excitement.

Isis had shrieked for Mary who’d spirited the kittens away, muttering about disgusting, morbid little boys, and Osi hadn’t spoken to Isis for months. But he had never stopped being obsessed by anything dead and the nursery windowsills were cluttered with the skeletons of birds and mice.

Kneeling down now to stroke the cat, Isis was just in time to see a neat wet purse slither out from under her tail on a trickle of pink water. The purse twitched and squirmed and Cleo twisted round to split the silk with her teeth and extricate the first kitten.

Isis cried out with a pang of pleasure. She’d caught her! This time Mary could do nothing about it; Isis would protect the kittens and Victor would back her up. In fact, a kitten might be just the thing to lift his spirits.

Cleo nipped through the little string that came from the kitten’s belly and rasped it with her tongue until it opened its toothless mouth and gave the tiniest squeak.

‘Clever Cleo,’ Isis said, settling down to watch and stroke and give encouragement. After the kitten came something frightful, wet and red that Cleo ate, and then there was another kitten, and another two. Four kittens, though the last never moved when Cleo freed it from its purse and its mouth stayed sealed despite a frenzy of licking.

The three blind kittens found their way, with a little nudging, to Cleo’s teats and, kneading with their tiny paws, began to feed, their pipe-cleaner tails twitching with the rhythm of their suckling.

Onceshewassurethatallthekittenshadcome,IsiswenttotellVictorthegoodnews.Ofcourse,sheshouldn’tdisturbhim,butsurelytappingsoftlyonthedoorwouldn’twakehimifhereallywereasleep.Therewasnoanswer.Sheopenedthedoorandpeeredintothedim,smellyroom.ThecurtainsweredrawnandVictorahumpbeneaththeeiderdown.Drawnbycuriosity,shecreptinside.

He was facing away from the door and she skirted the end of the bed to see his face. His eyes were closed, face sagging to one side, peaceful. The scar showed on his neck, shiny and raised and so much like a rasher that she almost expected the smell of bacon, but there was only the whiff of brandy and an empty glass on the bedside table beside a phial of pills. She leant very close to look and was startled to see his eyes open.

‘Icy,’ he said groggily.

She jumped back. ‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I came to tell you that Cleo has had her kittens and I thought you might like one?’

He drew himself up so that he was half sitting against his pillows, and patted the mattress. He was wearing a pair of Arthur’s pyjamas, dark red paisley, and his skin was the colour of raw pastry.

‘There’s one black and two tabby I can’t tell if they’re girls or boys and one dead, I’m afraid.’

‘Come here,’ he said and opened his arms. Isis hesitated. She didn’t want to touch the scar or to be too close to the smell of brandy and something else, stale and unappealing, but afraid of offending him, she leant forward awkwardly into his arms. ‘Dear little Icy,’ he mumbled into her hair and his arms were tight around her.

‘Isis!’ Mary came in with a tea tray on which sat a slice of date-flecked cake.

Isis jumped from the bed, blushing hotly. ‘Cleo’s had kittens and I was telling Victor and saying he could have one,’ she said. ‘I didn’t wake him, honestly.’

‘Kittens! Whatever next! I’m sorry.’ Mary put down the tray. She swished open the curtains, her expression unreadable. ‘As if Captain Carlton wants anything to do with kittens!’

‘I will have to decline the kitten, I’m afraid. But it’s perfectly all right.’ Victor added to Mary. ‘She’s quite a tonic, don’t you know?’

‘We’ll leave you in peace,’ Mary said, and yanked Isis through the door. ‘Whatever were you thinking? Going into a gentleman’s room on your own!’

‘He’s my uncle.’

‘And him not well in the head.’

‘He didn’t mind.’

‘Lord above.’ Mary rubbed her hands through her hair causing it to stand up madly. ‘And wherearethese famous kittens?’

Isis led the way to her room. Cleo was giving the black kitten a vigorous licking and the two tabbies were suckling. ‘That one’s dead,’ Isis pointed out.

‘That’s one small mercy,’ Mary muttered.

‘Aren’t they beautiful?’ Isis knelt down. ‘Clever Cleo.’ She stroked the cat’s head, and she arched her neck for more.

Mary tutted. ‘Well, you can’t keep them here for a start.’

Isis clutched Mary’s sleeve. ‘Pleasedon’t drown them.’

‘They’ll have to come down to the scullery.’

Isis scooped up the dead kitten, took it down to the kitchen, wrapped it in a duster and, muttering an apology, pushed it in the stove before Osi could get his hands on it.

She left the kitchen quickly before the flames crackled round the little corpse. Now was the time to carry out her plan for the budgerigars.

‘Don’t worry,’ she whispered to the panicking birds as she dragged the cage across the hall to the ballroom. That the ballroom was a vulgar extravagance, out of kilter with the rest of the house, was Arthur’s oft stated opinion. In his heyday, before the twins were born, and in a fit of grandeur, Grandpa had had it built on to the back of the house, along with the adjoining orangery, but for years there had been no parties and no need for it at all. Now its tall mirrors were dull and spotted and the windows looked through to the broken orangery with its wizened fruit.

Isis closed the door behind her and unlatched the cage. At first the budgies took no notice and then the blue one hopped through the entrance into thin air, and with a frightened screech wheeled out into the room on unpractised wings, clumsily looping round the ceiling and bashing itself against its reflections before finding a perch on the chandelier. The other bird soon followed, sending a squitter of droppings down onto the parquet and shrieking until at last it found its mate and they huddled together amongst the startled tinkling of the crystals, crooning and preening.

They were way out of reach up there and they could have the ballroom to themselves – they’d only need seed and water. Cleo and the kittens would never catch them and nor would Osi.

Thinking she caught a glimpse of movement in a mirror, Isis turned to catch her own white face, her hair in its awful childish pudding-basin cut, her face a plain, pale pudding too. She tore her eyes away, went out quick and shut the door.

IHAVEN’T SET EYESon my brother for years. But I know there’s something wrong because the bucket system’s broken down. I will go up today. I’ve said it before, but today I really will. Those broken stairs – it’s like contemplating Everest. But really it’s the fear that stops me; I’ll admit it.

Yes, I admit it. I’m scared of what I’ll find.