12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

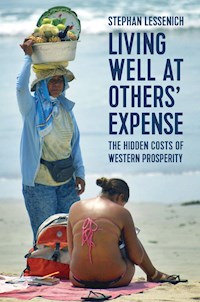

At the heart of developed societies lies an insatiable drive for wealth and prosperity. Yet in a world ruled by free-market economics, there are always winners and losers. The benefits enjoyed by the privileged few come at the expense of the many.

In this important new book, Stephan Lessenich shows how our wealth and affluence are built overwhelmingly at the expense of those in less-developed countries and regions of the world. His theory of ‘externalization’ demonstrates how the negative consequences of our lifestyles are directly transferred onto the world’s poorest. From the destruction of habitats caused by the massive increase in demand for soy and palm oil to the catastrophic impact of mining, Lessenich shows how the Global South has borne the brunt of our success. Yet, as we see from the mass movements of people across the world, we can no longer ignore the environmental and social toll of our prosperity.

Lessenich’s highly original account of the structure and dynamics of global inequality highlights the devastating consequences of the affluent lifestyles of the West and reminds us of our far-reaching political responsibilities in an increasingly interconnected world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright page

Epigraph

1

:

Next to Us, the Deluge

Chronicle of an accident foretold, or Rio Doce is everywhere

The global wealth gap – or I wish I were a dog

Externalization or the ‘good life’ – at the expense of others

Notes

2

:

Externalization: A Relational Perspective on Social Inequality

Capitalistic dynamics – and its cost

Externalization – the sociological perspective: living at the expense of others

Externalization structures, mechanisms and practices

Externalization – the psychoanalytical perspective: the veil of deliberate ignorance

Notes

3

:

Live and Let Die: Externalization as an Unequal Exchange

The categorical imperative in reverse

The curse of soya or who gives a bean?

Beyond soya – from the diary of the externalization society

The dirty will become clean: the global ecological paradox

The world in the Capitalocene: the ecological debt of the Global North

The imperial mode of living: is there a real life in the wrong?

It's capitalism, stupid! Wanting to know or not wanting to know, that is the question

Design or disaster – or democracy after all?

Postscript

Notes

4

:

Within Versus Without: Externalization as a Monopoly on Mobility

Semi-globalization

Hey ho, hey ho: away we go from the externalization society …

… and into the externalization society? The value of a passport

Citizenship rights and carbon democracy: the boat is full

Nothing to lose but our value-added chains? Working at externalization

Curtain up: the externalization society exposed?

Postscript

Notes

5

:

We Have To Talk: We Can't Go On Like This

Inequality! What inequality?

The battlefields of global capitalism

Imperial provincialism and the power of not having to know

The externalization society strikes back – on itself

Living in the eye of the storm: nothing will happen unless you make it happen

Epilogue: the Rio Doce in the face of disaster

Notes

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

159

160

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

161

162

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

163

164

165

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

166

167

168

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

169

170

171

155

156

157

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

Living Well at Others’ Expense

The Hidden Costs of Western Prosperity

Stephan Lessenich

Translated by Nick Somers

with the assistance of Stephan Lessenich

polity

First published in German as Neben uns die Sintflut. Die Externalisierungsgesellschaft und ihr Preis © Hanser Berlin im Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich, 2016

This English edition © Polity Press, 2019

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2562-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lessenich, Stephan, author.

Title: Living well at others’ expense : the hidden costs of Western prosperity / Stephan Lessenich.

Other titles: Neben uns die Sintflut. English

Description: Medford, MA : polity, 2019. | “First published … as Neben uns die Sintflut. Die Externalisierungsgesellschaft und ihr Preis.” | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018041739 (print) | LCCN 2018043141 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509525652 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509525621 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Social change–Economic aspects. | Globalization–Economic aspects. | Poverty–Social aspects–Developing countries. | Equality–Economic aspects. | Income distribution. | Environmental degradation–Developing countries.

Classification: LCC HM831 (ebook) | LCC HM831 .L4713 2019 (print) | DDC

339.22–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018041739

Typeset in 11 on 13 Serif by Toppan Bestset

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

It is a pervasive condition of empires that they affect great swathes of the planet without the empire's populace being aware of the impact – indeed, without being aware that many of the affected places even exist.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011)

1 Next to Us, the Deluge

The division of labour among nations is that some specialize in winning and others in losing.

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America (1973)1

Chronicle of an accident foretold, or Rio Doce is everywhere2

Mariana, 5 November 2015

In this mining town in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, the walls of two reservoirs containing the waste water from an iron mine burst, causing 60 million cubic metres of heavy-metal-containing mud – enough to fill 25,000 Olympic swimming pools – to flood the neighbouring community of Bento Rodrigues and enter the Rio Doce.3 Caused by a minor earthquake, according to the mine operator Samarco Mineração SA, the mud flowing out of the reservoir engulfed surrounding villages and some of their inhabitants. Three-quarters of the 853-kilometre-long ‘Sweet River’ became a toxic mix of iron, lead, mercury, zinc, arsenic and nickel residues, abruptly cutting off some 250,000 people from access to clean drinking water. After fourteen days, the tide of red mud reached the Atlantic coast and flowed out into the ocean, leaving behind a devastated ecosystem. At the Paris Climate Change Conference a few weeks later, the Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff described it as the worst environmental disaster in her country's history.

However striking the pictures may be of the mud-covered landscape and expired animals, of the dead river and its estuary, coloured a dirty red, the case of the Rio Doce is depressing not because of its uniqueness, but rather because of its perverse ordinariness. Rio Doce is everywhere. The causes of the ‘accident’, the way it was handled, its predictability and the reactions to it are typical of a state of affairs that exists worldwide. It is not only typical of an economic and ecological world order in which the opportunities and risks of social ‘development’ are systematically distributed in an uneven fashion. It amounts to a textbook example of the ideal type – the local, regional and global business-as-usual approach to the costs of the industrial-capitalist social model.

What happened at the Rio Doce was a perfectly normal catastrophe – and one that was waiting to happen. For many years, similar incidents have been occurring repeatedly, in Brazil and in other countries around the world with plentiful natural resources. Given the global division of labour, these countries are forced to exploit these resources as an economic strategy – and they do so in an intensive and sometimes reckless manner. The expression ‘they do so’, however, requires some qualification, because in many cases the business operations are contracted out to transnational corporations. In 2011, Brazil mined 400 million tons of iron ore, making it the third-largest producer after China and Australia. The formerly state-owned company Companhia Vale do Rio Doce was privatized in 1997 and renamed Vale SA. Alongside the British–Australian corporations Rio Tinto Group and BHP Billiton, it is one of the three largest mining companies in the world and the world's largest iron ore exporter, with a market share of 35 per cent.4 Together with BHP Billiton, it is the co-owner of the mine in Mariana through its subsidiary Samarco.

Samarco initially announced that the sludge from the burst reservoirs was not toxic and consisted mainly of water and silica. This announcement soon turned out to be false, as did the claim that the accident had been caused by earth tremors. More likely, the causes are to be found in familiar features of the administrations of ‘third-world countries’, namely corruption, clientelism and lack of controls. And, indeed, all these appear readily evident at first glance: there had been security concerns about the safety of the tailings dam for a long time, noted by the public prosecutor's office as early as 2013. In their criticism, the authorities also mentioned the immediate risk for the village of Bento Rodrigues, pointing out that no preventive measures of any kind had been taken to protect its inhabitants. The safety reviews ordered by Minas Gerais, the state with the largest ore-mining area in Brazil, were carried out not by independent experts but by members of the company itself. Almost at the same time as the dam burst, a commission within the senate, the upper house in the Brazilian parliament – where the mining lobby can always count on political support – voted for ‘more flexibility’ in the regulation of mining operators by the authorities.

So, is it all a question of underdeveloped governance, failing institutions, a ‘non–Western’ political culture? Perhaps. The other side of the chronicle of this ‘accident’ foretold is that, only a short time before it occurred, the physical stress placed on the dams had been significantly increased. In spite (or because) of the recent decline in world market prices, the two major corporations had increased the output of the Samarco mine to 30.5 million tons, a rise of almost 40 per cent compared with the previous year. In the case of Mariana, this market-flooding strategy had led to a large increase in waste from the mine and, as a result of this, the subsequent flooding of the surrounding area. Incidentally, the third and largest iron mine retention basin in Mariana is also showing dangerous cracks in its walls. And these are only three of 450 dams that hold back mining and industrial waste water in Minas Gerais alone. Around a dozen of these toxic reservoirs threaten the Rio Paraíba do Sul and hence, indirectly, the supply of drinking water to the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro and its 10 million inhabitants.

What happened at the Rio Doce is a disaster for nature – and for the people living in and off it – yet it was not a natural disaster. The background to it is anything but ‘natural’. Its causes are to be found in the structure of the world economic system: in the development models – which are influenced by this system – of countries rich in natural resources; in the global market strategies of transnational corporations; in the hunger for resources of rich industrial countries, and in the consumer habits and lifestyles of their inhabitants. What happened in Mariana, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and what is happening there every day, beyond the accidents and disasters reported by the media, is not caused by local conditions – at least not exclusively, and only peripherally, in the literal sense. What, from our perspective, happens at the ‘periphery’ of the world, at the outposts of global capitalism, is connected with the central hub – or, to be more precise, with the social conditions in those regions that believe themselves to be the centre of the world and that use their position of power in the global economic and political systems to dictate the rules that others must obey and whose consequences are felt elsewhere.

One of these rules – maybe even the most important one – says that, after ‘incidents’ such as the one that occurred in Mariana, life should return to normal as soon as possible. This does not apply only at the local level, where resistance to the mining industry is difficult to organize, for obvious reasons: whether they want to or not, the people of Minas Gerais depend on it. Four out of five households in Mariana rely on the mines for their existence. According to the mayor, Duarte Júnior, if they were to be closed, the entire village might as well be boarded up. In the wake of the ‘disaster’, people repeatedly took to the streets – not in protest against the mine's operators, but to demand that the mine start operating again as soon as possible. At the same time, there were, of course, ‘experts’, who sounded the all-clear or warned against unfounded environmental hysteria. Paulo Rosman, Professor of Coastal Engineering at the University of Rio de Janeiro and author of a hastily written report on behalf of the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment, declared that the Rio Doce was ‘temporarily dead’, but estimated that it would take only a year for nature to regenerate at the site of the burst dam and that the effects at the river estuary were ‘negligible’. He said that the situation there would stabilize in a few months and that the expected heavy seasonal rainfall would ‘wash out’ the Rio Doce, an ‘entirely natural process’.

The whitewashing of an ugly situation like this suits not only the multinational mining corporations operating in the area, but also the general public in the highly industrialized societies of Europe and North America. The people in these countries are deeply implicated in the causal chain leading up to the Brazilian disaster. They – in other words, ‘we’ – are partly responsible for the woes of Brazil and Latin America. They support the massive global depletion of natural resources and the environmental problems, as well as the working and living conditions in the countries where these resources are extracted.

Consider the case of the aluminium ore bauxite, which is found in many tropical countries.5 According to 2008 figures, Brazil is the third-largest producer of bauxite, after Australia and China and ahead of Guinea. Over the last decade, extraction has risen considerably in all of the countries with significant deposits. Between 2006 and 2014, the mining company Rio Tinto, for example, increased global extraction from 16 to 42 million tons (and iron ore extraction during the same period from 133 to 234 million tons). Bauxite was discovered and mined in Europe as early as the nineteenth century, but the deposits in the southern regions of the world are incomparably larger and more valuable in terms of industrial production. Practically all of the bauxite is used for the production of aluminium, which in turn goes into the making of many goods for daily consumption and for other needs in the countries that use these natural resources – such as neatly portioned and easy-to-use coffee capsules.

A huge amount of energy is required to produce the aluminium that is used to make coffee capsules: it takes 14 kWh of energy to make 1 kg of aluminium from bauxite, releasing around 8 kg of carbon dioxide in the process. This is not the only reason why the success of the aluminium capsules, popularized in advertisements featuring a handsome and world-famous actor, is so monstrous.6 In 2014, Germany alone consumed 2 billion of these coffee capsules, which only a few years earlier had been completely unknown. And the figure is still rising. According to the industry's estimates, the Nestlé subsidiary Nespresso sold 27 billion units worldwide in 2012. If each capsule weighs 1 g, this alone is equivalent to an annual mountain of aluminium waste weighing almost 30 million kilograms. And that is just one year, just coffee capsules, and just one manufacturer. Despite all this, Nespresso is even praised for using pure-grade capsules that are easier to recycle, while its competitors just put an aluminium lid on their much heavier plastic containers. The company's advertising slogan, ‘Nespresso. What else?’, is thus also backed by environmental claims.

But let's be honest – without sarcasm. Instead of savouring the ‘extraordinary taste’ (‘Savour our Grand Cru varieties from three gourmet aromatic families’, rapid delivery with the Nespresso mobile app), we should think about the bitter aftertaste of the actual production and consumption conditions. Our brief enjoyment of a cup of coffee at home comes at the cost of intensive bauxite mining in Brazil's rainforests. For our coffee at the end of an exquisite, but heavy, dinner, ‘somewhere in Africa’ resources are plundered, natural habitats destroyed, and toxic waste reservoirs and dumps filled. And executives consume coffee in the conference rooms of their globally operating firms as a quick-acting stimulant to help them keep the wheels of business turning – the wheels that produce our prosperity but that will unfortunately – and inevitably – run over other people in far-flung parts of the globe.

And yet this is only the tip of the iceberg as far as the European and North American coffee capsule hype is concerned. There is also the matter of the working conditions in the Brazilian mining industry; and then there is the fact that the toxic waste occurs not only as a result of mining the raw materials in the tropics but also through its re-export there from the richer parts of the world; and, finally, the social, economic and ecological aspects of coffee growing, harvesting and transport to the coffee-consuming centres of the world. Moreover, the coffee value chain, the parts of the world where these little capsules are produced and consumed, is itself just the tip of an even larger iceberg, a gigantic global process of perpetual redistribution of profits and losses.7 Be it cotton production or soya bean cultivation, the ubiquitous SUV or smartphone mania: ‘Rio Doce’ is everywhere.

More precisely, the flooding of huge tracts of land with toxic waste water from the extraction of natural resources for the Global North could have taken place anywhere – anywhere, that is, in the Global South. There are countless ‘Rio Doces’ in the world, and it is no coincidence that most of them flow through southern regions. Or else they no longer flow there because their water has been cut off by the North – like the water of the Rio Doce, which has been transformed into a slow-moving, gelatinous red mass. Thus, to tell the story of the ‘accident’ at the Rio Doce, the narrator has to tell two stories: the intersecting and linked stories of misfortune for some and good fortune for others.

It is this dual story that will be discussed in this book. It will look at the context, interdependencies, global relations and interactions – the relationality of world affairs. It will also consider the other, ‘dark’ side of the modern Western world, its rootedness in the structures and mechanisms underpinning the colonial domination of the rest of the world.8 It will be concerned with the production of wealth and the enjoyment of luxury at the expense of others, and with the relocation of the costs and burdens of ‘progress’ to other parts of the world. And there is a third story to be told – that of the reluctance to acknowledge this dual story, its suppression from our conscience, its omission in the social narratives of individual and collective ‘success’. Whenever we speak about our prosperity, we should not remain silent about the associated, interwoven and causally connected hardship of other people elsewhere. And yet this is precisely what happens all the time.

The global wealth gap – or I wish I were a dog

We can also examine life at the expense of others from a different perspective: that of social statistics. Although the resulting view might appear at first glance to be more abstract, it turns out to be just as striking as the pictures from the hell of Brazil's red toxic waste. Just in time for the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos, Oxfam, the international aid organization, presented impressive data on worldwide social inequality.9 The study confirmed the continued widening in 2016 of the global wealth gap observed in recent years, whereby the wealthiest 1 per cent of the world population owned as much as the remaining 99 per cent. In other words, a small group of rich citizens had the same share in global wealth as the vast remainder of the world's population. In this way, the 2011 protest slogan ‘We are the 99 per cent’ coined by the Occupy Wall Street movement was given a statistical blessing on a global scale. An even more impressive Oxfam statistic, on the face of it, was the fact that the eighty richest people in the world had at their disposal the same amount of material resources as the entire bottom 50 per cent of the global population.

As absurd as this ratio may sound – 80 against 3½ billion – figures like these also run the risk of misleading an interested public, or rather of saying what they want to hear. They suggest that the problem of global social inequality is basically the fault of an extremely small group of super-rich citizens and that the solution is therefore to be found in a policy of properly taxing these few dozen multi-billionaires – if not in the hands of the world's largest earners themselves, as exemplified by generous magnates like Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg. It is true that the wealth polarity demonstrated by the Oxfam data is nothing short of scandalous. And there can be little objection to an internationally coordinated taxation policy for global financial transactions, for example – as Thomas Piketty, the rising star in the economics firmament, recently demanded – except for the unlikelihood that it could be enforced politically or managed administratively.10

But the heart of the problem – unfortunately, one might be inclined to say – lies much deeper. The social diagnosis ‘wealth: having it all and wanting more’, as the title of this Oxfam study so eloquently puts it, describes the way of life, interests and ambitions not only of the ‘upper ten thousand’ of this world. Having it all and wanting more is not just the pragmatic agenda of these happy few at the upper end of the social wealth distribution scale, the object of the righteous moral indignation of ordinary citizens urgently demanding a significant redistribution of wealth. Essentially, the description might apply equally well to the lifestyle, sentiments and wishes for the future of a vast majority in the societies of the world's affluent countries. The attitude of having everything and wanting more is not the prerogative of those ‘up there’. Wanting to safeguard one's own prosperity by depriving others of theirs is the unspoken and unacknowledged motto of ‘advanced’ societies in the Global North – and their fundamental collective deceit is to deny the dominion of this distribution principle and the mechanisms for securing it. On a worldwide scale, the average citizens of the Global North are ‘up here’ when it comes to the national distribution of wealth – and we are quite happy to blithely ignore the situation of those ‘down there’.

This is completely understandable – not only because there are massive and continuously growing inequalities, visible to us today quite literally ‘on our doorstep’, but also because, if we were to look beyond the national distribution of wealth, we would discover something quite monstrous. In fact, once we have become aware of the enormous differences in income between the richest and poorest regions of the world, if only in dry statistical terms and figures, we cannot really carry on as before.11 The global inequality scale calculated for 2007 by the American sociologists Roberto Korzeniewicz and Timothy Moran shows that practically all income groups in European countries are among the wealthiest 20 per cent of the world population; in Norway, even the 10 per cent of the population with the lowest income are still among the wealthiest 10 per cent in the world. By contrast, a large part of southern Africa – 80 per cent of the almost 100 million people living in Ethiopia, for example – are among the poorest 10 per cent in the world.

To be clear, this is not about trivializing – much less denying – the social inequalities of varying degrees that exist in all countries. There is poverty in Germany and there are rich people in Ethiopia. A comparison of the situation in the generally affluent societies of the Global North – with, on average, a high standard of living, extensive options for shaping their lives and considerable consumption of resources – and the conditions in the, on average, much poorer societies in the Global South, which have fewer opportunities but which also consume less, does not mean that the internal inequalities on both sides should be overlooked. It should, nevertheless, make us aware that something like Piketty's much-acclaimed and widely discussed treatise Capital in the Twenty-First Century offers a very one-sided view. The French economist shows that there are rich people in the wealthiest countries of the world who are becoming even richer and who – in contrast to the prevailing idea of meritocracy in these societies – owe their position and its consolidation essentially not to their own efforts but to the exploitation of inherited capital. What his illuminating study fails to look at, however, is the fact that a similar structure has established itself on a global scale.

If, unlike Piketty,12 we look not only at the dynamics of inequality within the societies of the United States, the United Kingdom and France – not to mention Japan and Germany – but expand our vision to consider a global structural pattern of inequality between societies, we will once again find the wealthiest 10 per cent becoming increasingly rich at the expense of the rest. This 10 per cent is effectively made up of the five countries mentioned taken together. Their collective position at the upper end of the global wealth distribution scale is not due – and certainly not solely due – to the ‘industriousness’ of their citizens or the ‘productivity’ of their economies, but to a large extent to their strategic position in the world economy and the historically inherited ‘capital’ that comes with it. On a global scale, the inequality between rich and poor countries is even greater than the inequality between the richest and poorest population groups in the most unequal countries of the world – in other words, even more glaring than in a country like Brazil. Likewise, the relative inequality of opportunity resulting from the good fortune of being born in Germany, compared with the misfortune of being born in Brazil, is more pronounced than the unequal distribution of opportunity that the lottery of life offers to new-born babies within German or within Brazilian society.13

One thing that we thus tend to ignore in our latitudes, and that is inevitably absent from a perspective focusing on the wealth of individuals and exclusively on inequalities within society, is the fact that the national distribution patterns are embedded in a wider global structure of inequality – one that, it seems, is invisible and meant to remain so. In their book Unveiling Inequality, Korzeniewicz and Moran play a statistical game, inventing a fictional society consisting solely of the dogs kept as pets in US homes.14The average maintenance cost per household of these pets in 2008 becomes the ‘per capita income’ of this notional society. And guess what? This country, ‘Dogland’, ranks as a middle-income nation, above countries like Paraguay and Egypt, and better off than 40 per cent of the world's population. By this reckoning, it's better to be a dog – at least in the United States.

The authors use this small statistical game merely to illustrate the unsuspected scale of social inequality in the world. But the sudden wealth of the united pooches of America also illustrates the plausibility of the idea that we do not wish to know about these extreme inequalities – and much less about the fact that our wealth, reflected in the relative income ranking of the inhabitants of this virtual canine republic, not only stands in glaring contrast to the poverty in large areas of the world but also is connected with it – in other words, that our relative wealth can be understood only in relation to the lower income and more limited options and opportunities available to the vast majority of the world's population. The positions in the global inequality structure are a function of one another: some do ‘well’ or are better-off because others do ‘badly’ or are worse-off.

This is something that people appear to be simply unwilling to talk about, however. In public discussion in the affluent regions of the world, the connections between ‘our’ wealth – however unequally it might be distributed – on the one hand, and the working, living and survival conditions outside the world's economic and political centres, on the other, appear still to be a ‘secret’ to which only Marxist groups, development policy organizations and Pope Francis I are privy. And there are very good reasons – at least from a subjective point of view – why we want to hear nothing about these connections, between wealth and poverty, prosperity and deprivation, security and insecurity, opportunity and lack of prospects: as soon as we recognize and acknowledge these connections, we cannot but question the fairness of the resulting inequalities – or at least find it extremely difficult to justify our own privileged positions.

It is thus quite understandable that there should be resistance to such insights and also fear of the consequences that changes in global inequality would bring with them. We members of affluent societies have much more to lose than our chains.15 The fact that we secretly fear giving up our privileges suggests that we are aware of the global conditions on which our lifestyle depends. Nor does it surprise social analysts that we prefer to suppress our dawning awareness of the facts, that we don't want to hear about our lives being led at the expense of others, or that we prefer to conveniently ‘forget’ any feelings of unease this might cause us. It is precisely the purpose of this book to confront this forgetting.

Externalization or the ‘good life’ – at the expense of others

The complex connection outlined – or at least, touched on – so far concerning the life of some at the expense of others will be examined in this book from the point of view of a single term, namely ‘externalization’. To externalize means to move something from the inside to the outside. The accusation normally levelled at organizations or businesses that do not pay for the environmental damage they cause and benefit from, by passing on these costs to innocent third parties, can also be applied to larger social units. The rich, highly industrialized countries of this world transfer the negative effects of their actions to countries and people in poorer, less ‘developed’ regions of the world. The wealthy industrial nations not only systematically accept these negative effects but also count on them – the stakes are worth it for them. The entire socioeconomic development strategy of European and North American industrial society has always been based on the principle of development at the cost of others. In this sense, externalization means exploiting the resources of others, passing on costs to them, appropriating the profits, and promoting self-interest while obstructing or even preventing the progress of others.

Externalization is not merely an abstract ‘social’ strategy or the effect of a self-perpetuating and actor-less systemic logic. It is true that externalization describes the logic by which the global capitalist system works. But it is pursued by really existing social actors – not only large companies and political leaders, economic élites and powerful political stakeholders. Even if the wealthiest owners of capital and transnational companies pull the levers in the externalization society, the system is also shored up by the tacit agreement and active participation of large segments of society. ‘We’, citizens of the self-proclaimed ‘Western’ world, live in externalization societies – in fact, in the large externalization society of the Global North. We live in an externalization society, we live with it, and we are happy to accept it. Of course, the good life is also unevenly distributed here. The top fifth of rich societies have the greatest global opportunities. But in global terms, ‘all of us’, the wealthy citizens of the world, are better-off because others are worse-off. We are well-off because we live off others – off what they achieve and suffer, off what they do and put up with, off what they bear and have to accept. This is the international division of labour, which the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano described critically almost fifty years ago: we have specialized in winning, and the others in losing.16

We live in a society that by way of externalization – at the expense and cost of others – stabilizes and reproduces itself, and that can in fact stabilize and reproduce itself only in this way. This form of social organization, this mode of social development, is not at all new. ‘Externalization society’ is not a strictly modern diagnosis – like Ulrich Beck's diagnosis of a ‘risk society’, basically describing the new living conditions resulting from the rise of industrial technologies in the post-war world.17 The externalization society is not something that has appeared only recently, and as such it is not simply the latest version of modern civilization. ‘Externalization’ is not a diagnosis of our times but rather an analytical structural formula. ‘Externalization society’ is a generic term rather than a contemporary concept. Modern capitalist society has always been an externalization society – even if it has never admitted it. Capitalist societies are externalization societies, albeit in historically changing forms, with evolving mechanisms and continuously shifting global constellations.

It is this constant mutation of the externalization society, the long history of the constitution and reproduction of Western and Northern affluent capitalism at the expense of the Global South, that also gives the term – coined today and applied to the present – a contemporary diagnostic note. The social structure and patterns of externalization have taken on a new form in the last quarter of a century with the implosion of state socialism and the global spread of the capitalist production and consumption, working and living model.18 In principle, there is no longer an ‘outside’ in the global society to externalize to. The likelihood has risen that the social and environmental costs of industrial affluent capitalism are not simply offloaded elsewhere, far from the originators and beneficiaries, but rebound on to them – in other words, us. And it doesn't take much imagination, but merely observation and analysis, to anticipate a huge increase in these rebound effects in the near future.