Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Written in rhyming couplets 'Losing It' is the story of Lucy, a luscious young virgin who goes to London to try losing her virginity.

Das E-Book Losing It wird angeboten von Muswell Press und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 122

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

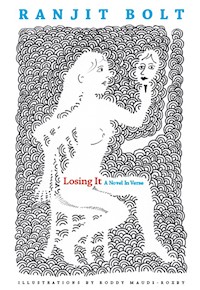

RANJIT BOLT

Losing It A Novel In Verse

ILLUSTRATIONS BY RODDY MAUDE–ROXBY

In Memoriam, Sydney Bolt 1920-2012

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

About the Author

Copyright

ONE

I thought I’d start by bringing in

My beautiful young heroine –

Lucy, as lovely as the day

Is long, or almost, anyway.

And yet, for all her loveliness,

She had to suffer the distress,

With twenty less than two years off,

Of being the mock, the jeer, the scoff

Of all her friends and peers, because,

Not mincing words with you, she was,

At eighteen – don’t be shocked at this –

As virginal as Artemis!

And whereas, long ago, Lord knows –

In Homer’s time, or Cicero’s

Or many ages I could name,

So far from being a cause of shame,

Such purity was highly prized,

Virginity being recognised

As a most honourable state,

Today a girl must get a mate,

And if she lets the time slip by

Without one, people wonder why,

The taunts and brickbats start to fly.

In these lewd times, virginity

Is practically a stigma we

Wear more reluctantly each day

After the age of – sixteen, say.

Instinctively, young Lucy knew

A pretty-boy would scarcely do –

She snubbed them time and time again –

She must have someone with a brain.

She was, herself, no quarter-wit

(In fact, the total opposite)

And would prefer a clever fellow,

Be he as plain as straw is yellow,

To someone dull, or dim, or dumb,

Although as handsome as they come.

How right she was! There’s nothing worse

Than being unable to converse

On equal terms with someone who

You’ve picked to share a bed with you.

It breaks your heart when, after all

The night’s cavorting, they let fall,

Over the eggs, or muesli, stray

Remarks, opinions, that betray

A total want of intellect –

Romantic fantasies are wrecked

And, as the grisly meal drags on,

You’re praying for them to be gone.

She’d had, for three years now, or more,

Good-looking morons by the score

Pursuing her – they were a bore.

But, strange to say, she hadn’t met

A bright boy she could fancy yet.

Some had been ugly and not quite

Proportionately erudite,

While others looked quite cute, and were

Smart – but not smart enough for her.

The search was profitless and long.

Sometimes she almost got it wrong –

Thought she had found the perfect person

In fact could not have picked a worse one

Was ready to perform the act,

Or nearly, but escaped intact.

And so, as three years came and went,

She’d stayed in her predicament,

Just like a sweet, unwritten tune

That hoped to be composed quite soon.

Virginity, my curse on you!

What dire lengths I was driven to

To shake you off in my own youth!

You drove me mad, and that’s the truth!

And then it happened, quite by chance

All gone were shame, and ignorance

As, man instead of bashful boy,

Heart flooded with conceit and joy,

I ran round Oxford screaming out

The news, lest there be any doubt,

Dismaying friends, naming the girl,

And startling tourists in the Turl.

As spots to get deflowered in go

London’s the likeliest one I know

And there it was that Lucy hied.

Her great-aunt happened to reside

Near Hampstead Heath, and she had said

That Lucy could have board and bed

For just as long as she might need

To do the necessary deed.

Her parents worried, but agreed

(If they had tried to thwart her aim

She would have set off all the same)

But yes, they fretted. Who would not?

Lucy in London – that fleshpot!

That hydra, readying its maw

To swallow their sweet daughter raw!

And was she raw! – completely green –

Despite being nubile, and nineteen,

And born in an anarchic age

When teenage pregnancy’s the rage.

Her friends were all ahead of her

And that was the most poignant spur

To Lucy’s urgent quest: peer groups,

While best shrugged off as nincompoops,

Are never easily dismissed –

It takes real gumption to resist

The constant pleasure they apply.

Her parents knew this, which was why

They didn’t stand in Lucy’s way

Though they were deeply troubled, nay

Distraught.

Within a day or two

A cab climbed Fitzjohn’s Avenue

With Lucy in the back. “So this

Is it! The great metropolis!”

She murmured. “I’ve a shrewd idea

I’m going to rather like it here.”

Mind you, the place she’d picked to live

Was hardly representative:

Hampstead, which roosts high up above

The city, like a Georgian dove,

With more quaint nooks and strange dead ends

Than teenage girls have Facebook friends.

Its narrow, ancient streets, its squares,

Bankers’ retreats and luvvies’ lairs,

Many regard as rather twee

While still allowing this to be

A beautiful and charming spot.

“Was it Well Road, then, luv, or what?

Coz if it was, we’re bleedin’ ‘ere,”

The cabbie growled, then gave a leer,

For all he’d had a rotten day,

And added: “You care now, eh?

There’s lotsa dodgy blokes out there.”

Then gawped as he discharged his fare,

For he, if anyone, would know

That figures such as hers don’t grow

On trees. He watched this living ray

Of vernal sunshine walk away,

In his wing mirror for a while,

The day’s best looker, by a mile.

Her aunt’s house was a Gothic pile

Close, as I said, to Hampstead Heath.

It made beholders catch their breath,

If they had any taste at all,

For it was cut out to appal,

Quite perfect in its hideousness

You’d shy away from it, unless

You are the type that can enthuse

About redundant curlicues,

Arches that make no visual sense

And other such embellishments,

Which covered it, and which belong

To the New Gothic style gone wrong.

In short, this mansion was a mess

(Though quite imposing, nonetheless).

She pulled the bell-pull, and a weird,

Lugubrious butler soon appeared,

Got up in garb of dismal black

More suited to a century back

Than any menial of today.

His manner suited his array –

Silent, and solemn as the tomb,

He ushered Lucy to her room.

”Dinner will be at eight,” said he,

Then turned about decrepitly

And slowly sidled off.

“Queer sort!

Quite scary house, too,” Lucy thought,

“I wonder if I’ve boobed? Ah well,

Stay positive – too soon to tell –

You pull yourself together, girl –

We’re damned well giving this a whirl!”

By chivvying herself this way

She kept anxiety at bay

Till it was suddenly dispelled

When, wafting through the house, she smelled

The marvellous, savoury yet sweet

Aroma of some roasting meat

And fear gave way to appetite.

At table they were three that night -

Unless you count the jet black cat

That, through the evening, mutely sat

On Aunt Alicia’s ancient knee.

“So here you are, my dear!” cried she

Lolling, contented, in her chair

And smiling with a wicked air.

She wrapped her great black woollen shawl

About her, and tipped back the tall,

Black, pointed hat upon her head

While, with the gaze of the undead,

She scrutinized her lovely niece.

“Algernon, pass the brandy, please!”

How typical the old witch looked –

Eyes brightly twinkling, nose hooked,

While kindness, in her gaze, was blent

With something more malevolent.

Much, to be frank, was pretty strange

About her ménage. Its mélange

Of things and people who’d just slipped

Out of a Hammer Horror script:

Her butler, not to badmouth him,

Seemed, if not evil, somewhat grim,

Added to which, the mansion where

This quite grotesque and gruesome pair

Hung out, posed questions by the score:

Scuttling footsteps scraped each floor,

You couldn’t name one feature which

Was not replete with Gothic kitsch –

The goggling gargoyles standing guard

Over the horrible façade;

Long, lamp-lit passages that creaked,

Which rats patrolled, while barn-owls shrieked

Out in the grounds, and night-jars whirred;

Poltergeists, too, must be inferred –

Though nothing had quite moved as yet

Various objects seemed to fret

About their stationery state

And whisper: “We’ve not long to wait –

Just sit this silly supper out

And, brother, how we’ll shift about!”

But to my tale: Alicia had,

Some couplets back, addressed a lad

Whose age was more or less the same

As Lucy’s – Algernon by name,

He being her grandson, and in truth

As weird and off-the-wall a youth

As she a crone. He sat beside

His cousin, yet he hadn’t tried

To start a conversation – no,

Completely mum he was, as though

Deaf, dumb and blind, so unaware

He seemed that she was sitting there.

This baffled Lucy. All night long

He shunned her like a nasty pong,

She’d never been so dissed, so scorned -

She ventured a remark, he yawned

And seemed to wish she’d venture none,

As though he might have had more fun.

In Purgatory.

It’s often true

That if we’re paid attention to

By someone of the opposite

Gender, we’re not impressed one bit,

But if we’re shown no earthly heed

A sudden, quite compelling need

Will soon start forming in our head

To get that person into bed.

That was how Lucy felt tonight:

He was no babe, but he was bright,

Nay, burned with intellectual fire

And that’s a licence to look dire,

Or certain women deem it so,

Lucy being one such, as we know.

A dazzling, cerebral flow

He kept up. He was plain, all right,

A truly horrifying sight,

The inverse of an oil-painting –

His eyes, his nose, his everything

Instead of going in, stuck out,

Or else the other way about:

His belly swelled, his arse caved in;

Low-browed he was, with sallow skin;

His teeth were riven by many a gat;

Legs long and thin, arms short and fat;

Eyes shrunk by bottle-bottom specs –

A walking antidote to sex

He seemed. Yet from his thick lips came,

On any theme you cared to name,

So much, and all so apposite,

And interlaced with charm and wit

That Lucy pardoned the disgrace,

The nightmare of his form, and face.

How lucid his opinions were!

To what a range did he refer

Of learned sources to support

Each judgement, each arresting thought

And scintillating aperçu.

But Lucy might, for all he knew,

Or seemed in the least bit to care,

Have been a table or a chair -

Alicia only he addressed

From start to finish, and caressed

With talk of literature and art,

The whole of which he knew by heart,

And on it had a trenchant view,

With politics and finance too,

History, philosophy, music, food,

And yet on none he seemed a pseud.

He was as well-read as they come –

As well as Voltaire, and then some –

Sweet Jesus, was he erudite –

He’d read all day, he’d read all night,

Read till his eyes yelled: “Look, you creep,

Stop reading! Get some sodding sleep!”

So Lucy guessed – correctly, too.

When midnight came, and they withdrew,

She had been pierced through with the pain

Of Algernon’s complete disdain.

She made her way upstairs to bed

Inwardly fuming, seeing red,

Resolved to show this dweeb, this swot

Just who was who, and what was what,

By bedding him, without delay.

Despite a quite exhausting day

She kissed goodbye to that night’s rest,

Was angry, lustful, and depressed.

At two a.m. her self-esteem

Still harped upon a single theme -

Fed up of waiting one more hour

To net him, and assert her power,

She left her room and off she crept

To find the one in which he slept.

Down creaking passages she went

With wild, lascivious intent

Till, at the end of one, she saw

A line of light beneath a door

And knew instinctively, at once,

That this room must be Algernon’s.

“I mean, who else’s could it be?

A little geek like that,” thought she,

“Scattering learned quotes around,

He’s studying something, I’ll be bound.

Given the vast amount he knows

It’s reasonable to suppose

He never sleeps, just reads and reads –

God save us from such bookish weeds!”

Thus Lucy fumed in her denial,

Wanting him madly all the while.

She knocked. No sound. So why the light?

“Sleeps with it on? I guess he might…”

Na – studying, the little nerd.”

Listening more carefully, she heard

The sound of fingers tapping keys –

“He’s writing something, if you please!”

She knocked a second time. “Come in!”

She entered, and was facing him,

She in her skimpy negligée,

He eying her, as if to say –

Well, something cutting, anyway.

He went on typing, which was rude

And, given so much pulchritude,

So lightly clad, at two a.m.,

Suggested an excess of phlegm

To say the least. He wasn’t dim -

A young girl was disturbing him,

Not any girl, but cute as pie,

At this late hour, he must know why,

Yet he did nothing, typed away

As if her legs weren’t on display,

Her lovely long white arms all bare,

And shoulders, under auburn hair.

“Algernon? Still awake?” said she.

“What’s that you’re working on? Tell me…

Some masterpiece?” “It’s… nothing much –

A novel… that is, not as such…

Call it a kind of overview –

My take on where we are, and who.

Well, now he’d talked to her at least –

Tacit hostilities had ceased

And that was something – not enough

But something. “Oh, it’s sorry stuff,

Dear cousin – just you wait and see –

No one’ll publish it,” said he,

But I’m incredibly behind

So, Lucy, if you wouldn’t mind…”

He went to work, she went away

Having done nothing to allay

Her pain, and even more impressed

With Algie, for she little guessed

That all North London, new to her,

Is basically just one big whir

Of diverse up-to-date machines

All churning chapters out, or scenes –

We just can’t help it, it’s a bug,

It ought to get us thrown in jug

But it’s as natural to our class

As to eat, sleep, or wipe one’s arse.

When the North London evenings come

Just listen, and you’ll hear the hum

Of writers, droning on like bees

On laptops, iPads, and PCs.

Nature’s soft nurse (that’s sleep, of course)

Soothed Lucy’s woes at last, perforce.

And even Algie’s pattering keys

Did have the decency to cease.

Later, the rosy Hampstead dawn

Woke on the Heath and, with a yawn,

Sensing it was too soon to break,

Pulled up the misty sheets to take

Another forty winks before

She gave the signal for the roar

Of London life to recommence.

From her nocturnal devilments

The witch returned. Each night she flew

Off on her magic broom, to brew

Fresh mischief up. But even she,

A votaress of Hecatë,

Was a tad weary, and could use

A reinvigorating snooze.

The butler, rested and awake,

As always, just before daybreak,

Tested his tardy, ancient legs.

Prior to preparing bacon, eggs,

Toast, coffee, for which all would ask,

His long day’s first, lugubrious task,

He brooded in the bluish-grey