6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

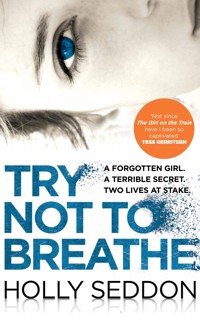

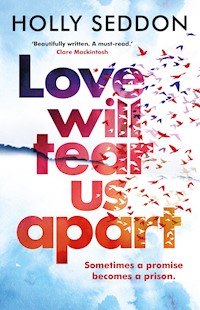

Shortlisted for the Hearst Big Books Award, 2019 Sometimes a promise becomes a prison. Fearing eternal singledom, childhood friends Kate and Paul make the age-old vow that if they don't find love by thirty, they will marry each other. Years later, with the deadline of their 30th birthdays approaching, the unlikely couple decide to keep their teenage promise. After all, they are such good friends. Surely that's enough to make a marriage? Now, on the eve of their 10th wedding anniversary, they will discover that love between men and women is more complex, and more precarious, than they could ever have imagined. As Kate struggles with a secret that reaches far into their past, will the couple's vow become the very thing that threatens their future? Love Will Tear Us Apart is a moving and heart-breaking exploration of modern love and friendship, from the bestselling author of Try Not to Breathe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

love will tear us apart

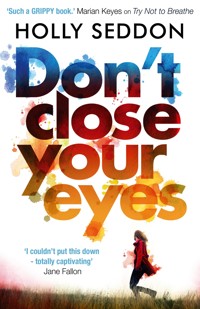

Holly Seddon is a full-time writer, living slap bang in the middle of Amsterdam with her husband James and a house full of children and pets. Holly has written for newspapers, websites and magazines since her early 20s after growing up in the English countryside, obsessed with music and books. Her first novel Try Not to Breathe was published worldwide in 2016 and became both a national and international bestseller. Love Will Tear Us Apart is her third novel.

love will tear us apart

HOLLY SEDDON

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Holly Seddon, 2018

The moral right of Holly Seddon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback: 978 178649 052 0Export paperback: 978 178649 506 8E-book: 978 178649 054 4

Printed in Great Britain

CorvusAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For James, forever

PROLOGUE

‘Are you sure?’ I ask, my hollow laughter fading into a wavering smile.

‘Deadly,’ he says. ‘Are you?’

I undo my jeans. I wriggle out of them and they fall to the floor. He holds his breath so I take off my T-shirt as well.

‘Are you sure about this?’ he asks, and I don’t know if he hopes the answer is yes or no.

‘If not you, then who?’ I say, and unclasp my bra.

‘Always you,’ he says, and he pulls his T-shirt over his head. ‘Always you.’

CHAPTER ONE

November 2012 – Sunday night

My husband used to get embarrassed by talk of how we got together. But once the story had been rolled around the dinner party table a few times to riotous appreciation, he seemed to flip position. He started to tell our story more often. He even added to it, ran his tongue over it, embellished and enlarged it. People are always fascinated the first time they hear it. ‘I didn’t know things like that really happened,’ they say. Or they laughingly tell their own tales, adding, ‘But I didn’t really mean it!’

We’re beyond that now. Even a story like ours can feel stale, and we don’t have any new friends to tell.

Stories change over time, just like the rest of us. ‘Time has a habit of ageing us,’ as Paul’s mum Viv used to say. And it’s not just the dogged chronology of putting one day in front of another, it’s the litter that those days scatter in our paths. The drip drip drip of post through the letterbox. The groaning repetition of school runs, after-school clubs and food shopping deliveries. The bittersweet climax that every holiday brings.

And then there’s the big stuff.

Harry was surprisingly easy. We waited a couple of years, then decided it was the appropriate time to try for our first baby. We had the regulation sex every other day for two weeks a month. By the end of the third month of ‘trying’, my breasts were tender and my belly was stirring with a gurgling nausea that all television shows ever had prepared me for. I knew even before I was ‘late’.

Because conceiving Harry was so reassuringly textbook, and conceiving Izzy a few years later was so tortuous, there was even a brief time Paul worried that I’d conceived our son though an affair.

While doctors assured us that secondary infertility was ‘very common’, especially with my medical history, for a while Paul became so certain of my infidelity that he stopped mentioning it, as if he was frightened that one day I would throw my hands up and say, ‘Yes, you cracked the case, he’s not yours. Now what?’

When I look at my eight-year-old boy with his flutter of deep, dark eyelashes and a delicate stoop in his narrow shoulders, I know with absolute certainty that he is all Paul’s. And Paul must know that too, now. Our son barely resembles me at all. In fact, neither of our children inherited my red hair and pale skin. But if I take an impassioned look, I can see why Paul would be suspicious. There were others, early on. Bodies that weren’t his. And that’s all they were, bodies. At the time, I had no idea he knew. Maybe I’ve underestimated how many of my secrets he’s unearthed, while he’s watched me so carefully and closely for the last ten years.

Perhaps he never really knew. Not the facts anyway: our onetime builder, fucking me dusty on the floor of the loft he’d just finished converting. A foreign exchange student I met on a doomed attempt to sign up for a master’s degree. A woman in a swimming baths, just once. Paul may not know, but he knows me. He knows me to my bones.

Perhaps he knew it was an inevitability. But I stopped casting my net outside of our marriage as soon as we started to try for a baby. Then my body was Harry’s. A vessel in which he could grow and twirl around, kicking me into funny shapes and swelling my flesh in a way I was scared it wasn’t capable. Once he was born, I only had eyes for him. My body was more valuable than I’d known. It had higher purpose, not just something to be crushed against a near stranger.

Now, even if I had those passions, I wouldn’t act on them. I would never give Paul a reason to cut me out of our family, to keep my kids from me, to start up anew with someone else. To do things that, until recently, I would have thought impossible.

CHAPTER TWO

1981

Last night, I dreamed about days I haven’t thought about in years. I dreamed about the sticky, irritable summer of 1981. The summer we were eight and ten-twelfths. The summer Britain ran amok outside of the stifled air of Little Babcombe, our tiny Somerset village.

The riots that year outraged my father, causing him to ruffle his Telegraph so violently I imagined it would crumble in his hands. Between imagining the IRA bombing our car to the Toxteth youths smashing our windows, I spent weeks convinced of imminent, newsy danger.

When danger eventually came, it sounded like a whisper. I was sent out to play and barely heard it.

My parents were locked in their own cold war by then, both retreating into their private bunkers. My father in his office, when he wasn’t flying to Eastern Europe, my mum dancing with friends at the Blitz Club and the Rainbow in her beloved London. There was a great deal of activity and quiet conversation about this going on among the staff at Greenfinch Manor, our family home, but I left it all behind to skim stones on the river, to make daisy chains or peel the cobweb layers of sunburn off my arms.

The air sagged, crickets rubbed their legs together in protest and pollen clung to my eyes and hair. The roads were carpeted with squashed frogs and slow worms, their innards dragged by cars and baked into the tarmac.

At the end of July, the whole country slipped inside to wave flags and wipe their eyes at the royal wedding. Most of their good cheer focused on Lady Diana Spencer, the doe-eyed nanny with impeccable credentials. Even my father joined my mother and the staff who were hovering in the lounge to watch the dress make its way into St Paul’s Cathedral, while I made my way out of the side door and into my mother’s abandoned studio to play with off-cuts of fabric and glue sequins to my fingernails.

By the beginning of August, I’d grown bored of skimming stones. I spent my days jumping from the climbing frame in the village recreation ground where the smell of the air was so strong you could taste the iron.

Or I lay on my belly by the stream, shielding my eyes from the orange sunlight with one hand, daisies tickling me through my dress, daring myself to take a running jump over the water.

One day, my gangly legs freed by summer shorts, I finally leaped. I cleared the stream easily, the water giggling below me. As I flew, I saw that the big rocks that had frightened me were just pebbles, magnified by the water. I saw tiny black minnows wriggling their bodies busily under mine, slipping downstream and out of view. I saw a reflection of my messy red hair fanning out from my crown like a cape.

I landed heavily, the perfumed grass rushing up to meet me. I sprang around and leaped again without a pause, back the other way, heart pounding. And again and again, daring my legs to stride out further each time, to stay in the air for longer. With every run-up, I took a step back, the momentum keeping me flying with cartoon whirly legs.

As I took my most daring jump, running up from the roadside to the stream, I felt my ankle twist under me, clicking like a cupboard door. I fell face first into the water, a slick black knob of a pebble bashing my cheek and narrowly missing my right eye. As I scrabbled out and crawled back up the bank, wet from chest to feet, I heard the thud of something in the grass behind me and rolled over to see two very thin legs coming into view.

‘You okay?’ Paul asked, squinting slightly as I got up onto my feet.

‘I’m okay,’ I said, wiping away my tears as if they were just stream water.

‘Where did you come from?’ I asked, suddenly angry and defensive in my embarrassment.

‘I was up in that tree,’ Paul said, lowering his eyes and pointing behind him with an arm that was more elbow than anything, drowning in a thin cotton polo shirt.

‘And what were you doing up there, spying or something?’ I’d cocked my hip to one side in a practised stance I’d seen on Grange Hill, watching it in secret with the sound down low.

‘No,’ Paul had huffed, turning to walk back to the tree.

‘What were you doing then?’

‘I was counting, if you must know.’

‘Counting what?’

‘Counting your jumps.’

Paul and I met every day after that. Never formally arranging it, but each leaving home straight after breakfast and spending the day together, only returning to our separate houses, briefly, to bolt down sandwiches that had been laid out for us, or to pick up our bikes or a pack of cards or a ball. At nearly nine, Paul was my first experience of habitual friendship, and I his.

Our children will never know the anxiety and pleasure of whole days and weeks yawning out to be filled, to be spent hiking through fields, making dens in hedgerows, swimming in the river. Parents with no idea or concern about where we might be.

We were wracked with fear almost constantly. Fear of the punks with their crunchy sugar-paste hair painted bright green or magenta. The ones we’d seen in town that loomed seven-foot tall in doorways, fingers pinching hand-rolled cigarettes burnt down to the nub. Fear of the IRA, who we were convinced had planted bombs across Little Babcombe. We threw whole days into terrorist hunts, inching under cars on our backs like tiny mechanics, checking for explosives. Fear of returning to school, of the daylight folding away into lessons. Fear of no longer being together.

Some time towards the end of the holidays, I was invited to have tea at Paul’s house. Before I went, my mum called me into her room and I sat up on her bed as lightly as I could, knowing she was still feeling fragile from the weekend. She brushed my hair so slowly I thought she’d fallen asleep a couple of times. She scraped each half into bunches, grimacing slightly as she grappled with the hair bobbles and set it all into place.

‘You look beautiful, Katie,’ she told me as she patted down my fringe and straightened the thick straps of my gingham dress. ‘Have fun on your date,’ she said with a smile.

I scowled. ‘Paul’s my friend. That’s all. I don’t even like him that much.’

‘Oh, I’m only teasing. Have fun.’

Paul’s house was so different to mine. Most of the downstairs space at 4 Church Street was taken up with the living room, with a small kitchen behind it and a smaller bathroom and separate toilet behind that. In the corner of the kitchen was a wooden table with a floral-patterned Formica top. Great play was made of pulling it out and lifting up the drop-leaf extension to make it a four-seater. Paul was wearing a thick round-neck jumper and was sweating around his ears and forehead.

‘I hope you like pizza sticks,’ Paul’s mum, Viv, said.

‘I’ve always wanted to try them,’ I answered honestly.

Paul’s dad arrived home as the Findus French Bread Pizzas were being placed on the plates; a salad of dark green floppy lettuce, tomato wedges and egg slices sat in a bowl untouched, salad cream on standby.

‘What’s this in aid of, eh?’ Paul’s dad boomed as he came in, winking at Viv and ruffling Paul’s hair as my friend shrank into his chair.

‘I’m only joking,’ he turned his wink to me. ‘We’ve all been looking forward to meeting the guest of honour.’

‘I can’t remember the last time we had dinner in here,’ Paul’s Dad said, opening a can of Hofmeister as Paul looked close to tears. ‘We’d usually be watching the telly, wouldn’t we, Viv?’

‘Stop it, Michael.’

‘Let’s put on some music, Viv.’

Paul swallowed and looked at his lap.

‘Do you like The Quo, Katie?’

‘I don’t really know, what is it?’

Michael – Mick – found this hilarious. He crunched the sticky play button on the radio-cassette player. I heard the soon-to-be-familiar de-dun de-dun de-dun of every Status Quo song.

‘Does your dad not like The Quo then, love?’

‘I’m not sure, I’ve only heard him listen to music with no words.’

The adults laughed.

‘It’s really boring,’ I added, enjoying the attention.

The pizza stick had gouged deep scratches into the roof of my mouth but I wished I could eat one every day. The little pieces of bright red meat like gems; the brittle cheese like a gold lattice. A nice change from the food that was made for us by Mrs Baker, our housekeeper.

I knew by then that Paul was ready for me to leave but every room held fascination. From the tiny WC and its sign, ‘If you sprinkle when you tinkle, be neat and wipe the seat’, to the beads hanging between the kitchen and living room. Photos of Paul coated every surface. I was fascinated by the videotape cases that had been made to look like old books. I wished my father’s old books had Disney videos hidden in them. Viv and Mick were delighted. Paul told me later that they didn’t even have a video player back then, they rented one for special events. They had recorded the royal wedding a few weeks before I visited. Mick had stood solemn-faced with his finger over the record button waiting for the exact moment the programme started as if it was his actual job.

Paul’s dad was ‘a jack of all trades’ and his mum was a nurse. I only understood what one of those meant.

When it was time to go home, Mick drove us.

‘It’s okay, I can walk from here,’ I said as his royal blue Austin Allegro reached the gates at the foot of my drive.

‘Are you sure? That looks like a very long drive.’

‘Oh, it’s fine,’ I said. ‘My father doesn’t like to open the gates to other cars.’

Paul looked wounded but his dad seemed amused.

‘Thank you very much for having me,’ I added.

CHAPTER THREE

November 2012 – Sunday night

I look across at my husband’s locked jaw, his thin black glasses pushed back into the groove on his nose, his forehead bearing down on the road ahead. He’s wearing a light woollen sweater and dark-blue jeans. I can’t see his feet but I know he has tan brogues on. I’m wearing an oversize knitted T-shirt that I like to wear in the car as it’s so comfy. My favourite jeans hug my legs and I’ve slipped off my knee-high boots so I can wriggle my socked feet in the fanned warmth of the footwell.

I watch Paul when he’s driving, it’s the most ‘zen’ he can be. He generally manages to tune out the bickering from the back, he doesn’t hear the radio, he claims to only hear me on the third try. I try, and fail, to imagine what is running through his mind. What is he planning, while I study him discreetly?

His wrists are as slender as they ever were, the same wrists I see on Harry. Paul’s are now covered in a thick, dark layer of hair that wasn’t there when he was eight and isn’t there on Harry’s arms yet. The bones are the same though. I’ve grown to love those bones.

‘Mum, Harry just said I was a himp-oh-pot-oh-mose.’

‘You can’t even say it!’

‘Harry, why did you call your sister a hippopotamus?’

‘I didn’t.’

‘You did!’ Izzy trills. ‘Liar!’

‘I didn’t!’

‘You did!’

‘MUM!’

‘This is ridiculous,’ I say, and I refold my cardigan in my lap. ‘I’m not getting involved with this silliness.’

Izzy starts to sob, quietly. When this doesn’t stir any kind of reaction, she grabs Harry’s arm and bites it, quick as a flash. Her baby teeth carve grooves in what little flesh there is.

Harry yelps and Izzy smiles. Before I can say a word, Paul slams on the brakes and shouts, ‘Harry!’ at the top of his voice.

‘She bit him,’ I whisper to the side of Paul’s head.

‘He goaded her,’ Paul says.

‘It’s been a long journey,’ I say.

‘There’s no excuse for them going feral,’ he says back, without lowering his voice.

‘This is nothing.’ I laugh but he doesn’t. Holiday exposure to the kids is always a shock to his system, and we left Blackheath seven hours ago.

The tick-tock of the indicator is the only sound. The engine holds our breath for us and we pull back onto the road and roll into the blackness ahead.

We finally reach our holiday cottage. In the back, Izzy has fallen into a dribbly sleep while Harry is drooping, close to nodding off. Paul leans across and pats Harry’s shoulder. ‘We’re here, time to wake up.’ As Harry shakes himself awake, Paul opens the back door and scoops Izzy up into a curly bundle. His right hand is tucked under her bottom while the other strokes the mahogany hair out of her sweaty face. She’s only four, but she’s a solid little unit. I notice his knees buckle a bit.

Breathing in the tangy air, heavy with ozone and the promise of sea, I take Harry’s hand. He’s dozy enough not to fight me off – a devastating new habit that’s taken effect over the last school year. We lean on each other as we walk up to the front door. The key is exactly where they said it would be. I’m giddy with relief.

‘Come on, Kate, she’s not getting any lighter,’ Paul says, shifting Izzy onto his hip. I fumble my way in, and feel for a light switch on the unfamiliar wall.

‘Oh, it’s beautiful,’ I say.

‘This is nice,’ says Harry, scratching his head.

‘This girl is definitely growing,’ says Paul, kicking his shoes off.

I know the layout of the cottage from the booking website, but it’s always different in the flesh. You can feel the temperature of a place, smell the air freshener and the remnants of what the previous guests cooked for their last, melancholy dinner. The whole place seems entirely unknown, clandestine.

This cottage really is lovely. And it should be. I wrote off three whole days finding just the right place. One pyjama-ed leg tucked under me, clicking through galleries of pictures until my eyes stung. So many pretty cottages had sofas that looked a little hard, or an uninspiring white oven in the sea-facing kitchen. The lovelier we’ve made our own home, the more this stuff seems to matter. Avoiding disappointment to the point of mania. And it has to be right. No distractions, it has to be right.

Paul pads upstairs and I follow closely behind to click on more lights, while Harry sits heavily on the bottom step.

‘Come on upstairs,’ Paul whispers hard. ‘Time for bed, Harry.’

Harry drags himself up to a wobbly stand and starts to plod up the stairs after us, before sitting back down to take his shoes off. I shouldn’t have bought him lace-up trainers, it takes for ever to get him in and out of them, which drives Paul to distraction.

I know full well that they’ve not brushed their teeth as we tuck them in and kiss their sweet, sweaty heads. I didn’t make them go for a wee either. I’ll play dumb through any accidents.

I run back into the black cold to fetch a carrier bag of journey-mess from the car. For a brief, chilly moment I think about lowering myself into the driver’s seat. I imagine moving my hands slowly around the soft curve of the steering wheel and gingerly feeling the smooth tip of the gear stick. But I don’t sit down. Instead, I lock the car with a thick satisfying click and wonder what it would feel like to drive home alone.

CHAPTER FOUR

1981

In my memory, my mum’s ill periods seemed more like long lie-ins. She’d be in bed but claiming that the rest was in preparation for going out to her studio. Theoretically, her studio was the place where she made jewellery and painted canvases or customised clothes.

Occasionally in the morning, I’d tip-toe into her bedroom to find the bed empty, and hear her throwing up in her bathroom. Once, I overheard Mrs Baker talking to her husband, who did the gardens for us. ‘She’s down with another bloody hangover.’ One of my first thoughts after Mum died was, ‘Hope you feel guilty now, Mrs Baker.’ It’s impossible to say how long Mum’s illness was sneaking around her body, interfering like a malevolent version of Beezer’s Numskulls, planting little cartoon bombs. Maybe it all happened like a flash flood and all those earlier episodes were just commonplace hangovers – or come downs – but either way, I didn’t appreciate Mrs Baker’s constant, open judgement.

I don’t entirely trust my recollections, though. My pace is off. Memories from several years can come in one big rush and neighbouring days can seem years apart. The past is a hall of mirrors and, besides, I’ve seen first hand how two children can have a totally different understanding of the same situation.

With all those caveats in place, I’ll say that by Christmas after the first bout of illnesses, my mum seemed fine. She was back in her usual clothes, up and out of bed most days, sometimes before lunch. Her blonde hair was always a little bit wild, thick like a lion’s mane and as shiny as shredded glass. She wore leather trousers and a lot of animal print. One time, she smeared a line under her eyes like Adam Ant but changed her mind when she saw me giggle. She was very young. Eighteen when she married my father, nineteen when she had me. My father, Roger Howarth, had been in his thirties. To her friends my mum was Suki, to my father she was Susannah. I think she’d also been Susannah to her own father but I never met that generation. Not on either side.

After the bout of sickness in ’81, Mum emerged newly interested. Dressing me up and sometimes dropping me at the bus stop in her old Jaguar, so long as the weather wasn’t too cold for the engine to start. My father hated that car, but my mother could never get to grips with the Alfa Romeo he bought her. And that never started in the cold either.

When I couldn’t hold my mother’s interest any longer, she returned to her London friends and I picked back up with Paul. At weekends, we peddled hard on our bikes to meet by the stream or cycle two abreast into Castle Cary, the nearby town. We’d whip by the crumbly orange Somerset-stone terraces, like cycling past rows and rows of LEGO.

We spent hours staring at the swans in the Castle Cary horse pond, daring each other to find out if they really could break a human’s arm. The big white birds eyed us with contempt as we nudged each other and tried to calculate their wingspan. Most days, we bought a five-pence bag of sweets, inspecting them carefully through the semi-transparent paper before committing, trying to avoid any blackjacks.

In September 1981, Paul and I turned nine within days of each other and our adventures moved indoors as the temperature dropped. I visited Paul’s house every weekend while my mum slept, shopped, or returned mothlike to the flame of London. My father stayed locked in his office. At Paul’s, we watched Grandstand and the wrestling with his dad, ate fistfuls of lardy cake, wrote songs using Paul’s tiny Casio keyboard and played card games like Rummy, Patience and Pontoon. We got really good at a game called Shit Head and I wish I could remember the rules. I certainly remember the giddy liberty of saying ‘shit’ without repercussion.

We briefly made up our own band. Naturally, Paul was the keyboardist because he owned the keyboard. We were heavily influenced by Sparks and Ultravox, whose megahit ‘Vienna’ we both loved. Our band was called The Captain and Kate, which I still can’t say without laughing, although I took it very seriously for the three weeks we were in circulation. The best part was that Paul came up with the name, which means that for some reason nine-year-old, four-foot-tall Paul really did want to be known as ‘The Captain’. He had a surprisingly emotional row with his mum when she asked if it was a word play on the Captain and Tennille and we disbanded soon after. The Captain. Even now, if a ship’s captain appears on TV, Paul only has to raise one eyebrow and we’re both in stitches.

In November that year, the tornadoes came, ripping holes in the country one Monday night. We convinced ourselves that they were coming back to hit Little Babcombe the next night and met after school to build a bunker in the disused coal shed in the Loxtons’ garden. We spent ages sweeping it out and covering the walls with cardboard and masking tape. The sky was dark grey when we started and pitch black by the time we finished. Our hands were thick with coal dust that had mixed with frost to make a punishing paste. Paul had already changed into jeans and a jumper but I was still wearing my royal blue school uniform and what had been a crisp white shirt.

We took out tins of food squirrelled from the cupboard, torches, a pack of cards and a tin of biscuits. A haul we figured was all pretty tornado-proof. After six, I called my house from the chunky rotary dial phone in Paul’s hallway. My mother answered, which caught me off guard. I asked to stay the night at Paul’s and was given a breezy okay. That night, sleeping bags rolled at the ready, we lay on Paul’s bed, topping and tailing. We were both wearing pairs of his pyjamas and our school shoes so we could act swiftly in case of emergency. The Z-bed was pushed against the window to protect us. We were prepared to run to the bunker when the winds came, and took it in turns to stay awake on tornado watch. We woke up on Paul’s bed on Wednesday morning, curled into each other like baby animals, huddled for warmth. The freezing air outside the house was calm, the bunker untouched. Before I ran for my school bus, Viv made us locate and return all the stuff we’d stolen, although we were allowed a biscuit from the tin afterwards. Later that day, I was given ten strong swishes of the cane across my blackened bare legs for turning up at school thick with coal paste and wild-eyed through lack of sleep. I didn’t go to Paul’s that night, I lay in the bath, running my classmates’ laughter and insults over and over in my head. I gradually let more and more scalding water into the tub until I couldn’t feel my feet and my temples pulsed and the red welts on the backs of my thighs went numb.

My father spent most of Christmas 1981 in his London office, dealing with something happening somewhere in Poland that involved his money but that didn’t concern me. My mum and I spent it in our pyjamas, Mr and Mrs Baker away visiting their grandchildren, the shelves gathering dust. We didn’t manage to cook the dinner and ate beans on toast with cheese grated on top for Christmas lunch. We didn’t watch the Queen’s speech but agreed to tell my father that we had. It was the best Christmas I ever had.

On the morning of New Year’s Eve, I came down in my nightdress to find breakfast laid out for the household. Grapefruit juice in a jug, tea in the pot, toast in the stand. Mrs Baker was back. My mother had called her so she could drive to London in the early hours for a very important party.

CHAPTER FIVE

November 2012 – Sunday night

‘We must decide what to cook for Saturday night,’ I say, as we inspect the kitchen, fiddling with the utensils and coffee machine, which is better than the one we have at home and is giving Paul stirrings for an upgrade. I want to lay the groundwork for Saturday night now, because if we leave it, we’ll have left it until Saturday afternoon and it will become a problem. Our anniversary meal will become an emergency, we’ll not know what we fancy, or where to get it, and the whole night will disintegrate into cold, unspoken nothing. My moment, my nerve, will be lost. Another ten years could trickle past.

‘Let’s have something local,’ Paul says, half of his voice lost to the inside of a cupboard he’s rooting through. He likes to have ‘local’ things. Cromer crabs in Norfolk, Welsh lamb in Wales, and Gloucester Old Spot in the Cotswolds. For a moment, I imagine him on these holidays without me. I wonder where he would go, if he could go anywhere.

‘I’m not really sure what food Cornwall’s famous for,’ I say, lightly.

‘Cornish pasties, do you think?’

‘Yeah, yeah. Clotted cream and pasties. Yum, let’s have a big bowl of clotted cream with a pasty on top,’ I say with faux belligerence that makes him smile at last. I search online while he pours us a glass of wine from the complimentary basket.

‘Seafood,’ I say, ‘and ale. Seafood floating in ale?’

‘Ooh, ale,’ he says, smiling easily now. ‘That’ll put hairs on your chest.’

I wish I could wrap this moment neatly and hide it away, among the boxes of baby clothes. I’m hoarding these fleeting moments even before they turn into memories.

In six days’ time, we’ll have been married for ten years. That’s quite an achievement by modern standards. ‘And they said it wouldn’t last!’ That’s the joke people make, isn’t it? No-one says that about us.

Ten years is tin, apparently, which I was at a total loss how to deal with. I can’t imagine what gifts this would have encouraged even in the olden days. A tin hat? In the end, I just cheated. In my leather holdall, I have a pair of cufflinks in a beautiful box tucked into a new tin can that’s been artistically ‘distressed’ to look like an old tin can. I also have a £500 first edition of Under Milk Wood.

Paul and I have always liked to make a quiet fuss over intimate events. Neither of us gets birthday or Christmas gifts from siblings, or parents. We don’t have sprawling, extended families to make a big deal about anything, so it’s down to us. It started a very long time ago, before we were ‘together’, even. With every pay rise and bonus, the prizes got bigger, the bar got winched up until the rope was so taut it squeaked.

Of course, I’ve not worked for a very long time so I suppose in the cold light of examination, Paul is buying both our presents. I don’t think he sees it like that and I try not to. It’s what he wanted and he never complains. Not to me. Lately I’ve wondered, when I’ve dared, if he’s described our set-up to someone new. If he’s allowed the corners of his mouth to turn down in symmetry with theirs, if he’s rolled his eyes at the disparities and the sacrifices, things I never considered he might resent.

The cottage is relentlessly white, still bright this late in the evening. The walls are panelled with pale painted timber, the floorboards washed in a similar shade. An overstuffed sofa is the colour of clotted cream and the creamy grey rug tickles our feet like sea spray. It’s white in a way only a holiday home can be.

The kitchen has huge suspended white pendant lights and the cream Aga makes my tummy flutter. Paul and I leave the curtains open and head into the living room. I place my glass on the windowsill and flop into a soft pale grey armchair next to a tiny window with just a slap of sea view. The deep dark blue is lit in peeps by the fat moon.

‘Dylan Thomas honeymooned in this village, you know.’ As I say it, I have my eyes closed but I know that an appreciative smile will be creeping across Paul’s face. I glance over. He too has flopped onto a sofa, eyes closed, empty wine glass resting on the arm. His feet are bare and his toes wriggle this way and that, this way and that, in time to music I can’t hear.

‘You’ve picked well, Kate,’ he says and I smile again. I walk over to top up his wine and he reaches for my other hand, stroking it just briefly.

‘Let’s take the kids to the beach tomorrow after breakfast,’ I say. The hug of the underfloor heating leads me to make bold plans I probably won’t fancy in the cold November morning.

I snuggle back down into the belly of the armchair, my head on a cushion that smells of cinnamon and nutmeg.

‘I could fall asleep right here,’ I say. And I hear the steady rhythmic breathing that tells me I’ve already lost Paul.

I take a sip of my crisp, floral wine, and reach into my pocket. It’s still there, of course. I don’t want to see it again, not yet. But I need to check it’s there.

CHAPTER SIX

1982

When it wasn’t showing gloomy pictures of the dole offices and unemployment queues that year, the TV news was filled with the Falklands war. Mick was suddenly furnished with all sorts of opinions on and information about Argentina and its people. Like much of the UK, I think, Paul and I had never heard of the Falklands. When Mick tried to explain to us why ‘we’ owned an island eight thousand miles away, he grew quickly frustrated by our questions.

‘I still don’t get why it’s ours,’ Paul whispered to me as he made us a Kia-Ora in the kitchen.

‘Maybe your dad doesn’t really know either and that’s why he’s getting cross.’

Mick had a tendency towards tearful patriotism in certain circumstances, and blanket disapproval of the upper echelons of British society in the next breath. While Viv clucked and cooed over pictures of the new royal baby in the papers that August, Mick had rolled his eyes and made cutting remarks about another mouth on the teat.

‘Dad’s a republican,’ Paul explained. ‘He doesn’t think we should have a queen.’

‘Oh, hang on boy, I wouldn’t go that far,’ Mick spluttered. ‘I just don’t think we should be paying for them, not with all these new ones being born.’

‘One new one,’ Viv chided. ‘Charles and Diana have had one little baby and it’s a bloody blessing after the year this country’s had.’

‘That’s how it starts, Viv.’ Mick grew animated. ‘You’ll see, they’ll have another one in a year or two, then another, then another. He looks like a randy bugger, that Charlie, and a nice young maid like her to get his hands on.’

‘Mick!’

My own parents never talked like this. They barely talked at all. And my dad had nothing but respect for the royal family. But Viv and Mick seemed to enjoy play-fighting. Paul was used to it and rolled his eyes but I couldn’t get enough, my face flushing with excitement.

‘You’re the only randy bugger around here, Mick Loxton,’ Viv laughed as Mick chased her around, trying to slap her bum.

‘Gave you one royal prince, didn’t I? Fancy another?’

‘Mick!’

Mostly, we had our eyes on September, and turning ten.

Ten was the big one. We started talking about turning ten almost as soon as we turned nine. Ten meant something back then. Nowadays, we’d no more allow our kids out on their own at ten or eleven than at five. They’re shuttled between playdates and wholesome activities and extra tuition with their feet barely touching the pavement.

But when our tenth birthdays finally came, we got jobs sticking up skittles at the local pub, The Swan. Paul had to beg his mum to let him do it. It meant a late night on a Tuesday – a school night. Paul’s dad Mick was all for it.

‘It’ll put hairs on his chest, Viv. A bit of work’s no bad thing for a boy and he’ll have our Katie with him.’

I was treated like one of the family by then. A fixture, so confident of my place in their world that I could let myself in the back door without knocking. I could touch the TV and the new record player with its built-in tape deck.

Mick collected us at the end of our ‘skittling shifts’ and dropped me at the bottom of my drive. His car smelled of warm ale and cigarettes and I was allowed to sit in the front because I was taller than Paul. My arms and feet ached from the night’s work: stop-start, stop-start, yank the skittles into position as fast as possible or get a wooden ball in the shins. The journey home was only ten minutes but my head would droop over the seat belt. There were no seat belts in the back. Imagine that now.

My mother’s attentions had increasingly turned to London by then. She talked vaguely about some fashion project or other with her art school friends, but the black marks under her eyes when she occasionally reappeared told a different story. I prided myself on being less gullible once I hit the lofty age of double figures. My father’s business was experiencing some ‘bumps’, whatever that meant, and Mrs Baker was called upon to stay past supper and babysit, which she did only nominally. In the end, we all just did our separate things.

I didn’t have to beg or plead with my parents to go sticking up skittles, I just left through the front door and let myself back in afterwards.

‘You’re so lucky,’ Paul would say, and he’d roll his eyes behind his mum’s back when she fussed and worried.

Sticking up skittles was hard work and poorly paid, but we were desperate to do it because it seemed so undeniably grown up. We each got a quid, a bottle of pop and a bag of crisps from Lorraine behind the bar. Lorraine was the landlord’s eldest daughter, the closest thing the village had to a glamour puss. Her clothes were bright and thin. I used to see her getting off the bus from Yeovil on a Saturday, arms hung with bags from Chelsea Girl, Etam and Topshop. Of course, looking back I realise how much more glamorous my mother was, how Lorraine would have killed for a wardrobe like the one that my mum left behind.

Back then, Paul and I never let on to each other how much we despised those wooden skittles and the sweaty red-faced skittle players who yelled at us for not sticking them up quickly enough. We never acknowledged the splinters in our hands. I often dropped my pound’s wages in the car on the way home, it was never about that.

Paul stockpiled his earnings, making a careful note of his running total in a little book from WHSmith. Any chips or sweets he bought were deducted from the running total in the front. Written neatly in the back was a list of things he was saving for.

After a few months, the sticking-up job ended abruptly. Letting myself in to 4 Church Street to wait for Paul one day, I found myself eye to eye with Lorraine from The Swan. She was at the foot of the stairs, struggling into her boots, makeup harsher in the hall daylight. Mick was sitting, skinny and shirtless, a few steps up from her. I was so surprised that I just turned and left, all of us wordless. He never mentioned it to me, or I to him.

I wasn’t an idiot, I may not have understood it all but I knew she wouldn’t have been there if Viv hadn’t been at work. I knew something must have happened, something adult. It sat in my gut, wriggling and ever present, and I was distracted by that when we played. After a few days, I blurted it out to Paul. Even then, he barely reacted on the surface. His lip quivered and he balled his hands up into little fists but he didn’t say anything.

‘So your mum’s right,’ I said, trying to lighten the mood. ‘Your dad is a randy bugger.’

Paul said nothing.

CHAPTER SEVEN

November 2012 – Sunday night

I wake up sometime after 4 a.m., alone in the lounge. I have the thick blanket tangled in my legs and my neck is cricked. For a moment, I don’t know where I am or why I’m folded instead of flat and I blink helplessly into the dark. Paul must have turned the lights off when he woke up and took himself to bed. I wonder if he watched me a while before leaving and flush at the thought. I tip-toe upstairs and try to remember which child is in which room, check their breathing and sniff the air for accidents.

I creep down the hall, the floor squeaking under foot. The master bedroom is the whitest of all. Chalky white walls, thick cream carpet, white curtains, white bedding, white lamps. Even in the deep of the night, it glows like a harvest moon. I discard my clothes in a heap and shiver into my pyjamas.

I lift the covers as carefully as I can, trying not to let the cold nip at Paul’s bare arms and feet. I shuffle in sideways and turn my back to him and am asleep seconds later. When I open my eyes again, Izzy is between us. Her whirligig legs work their way up and down my back as she burrows, snoring, into her father’s ribs.

‘How long has she been in here?’

‘Not sure,’ Paul whispers back. ‘I woke up and she was already here.’

I turn over slowly and kiss her puffed-up pink cheeks, smelling the sweet perfume of sleep. Paul smiles and kisses the top of her head, her dark hair tangled but shining. She’s one of those kids you just can’t keep your hands off. Even though she’s past toddler age, we’re always carrying her, cuddling her, kissing her and getting in the way of her busy work with our pleas for attention and affection. Since Harry turned a corner and immediately found all affection abhorrent, Izzy has borne the brunt even more.

I cuddle up to her solid little back and fall back asleep until the sun streams in and she’s sitting up demanding breakfast.

In the kitchen, I fumble around finding mugs and filling the kettle from a surprisingly feisty tap that sprays up my arms and jolts me awake.

‘Did you bring anything for breakfast?’ Paul asks without looking up.

‘No, why?’

‘The kids need to eat something.’

‘Isn’t there anything in the hamper? The website said they’d provide breakfast for the first day.’

‘They don’t like it, it’s all adult stuff.’

‘What constitutes “adult stuff”?’ I lower my voice. ‘Crack cocaine and dildos?’

Paul lifts his head and stifles a grin. ‘It’s granary bread and marmalade.’

I turn to look at the two panicky faces. ‘Oh guys, marmalade on toast won’t kill you.’

‘Dad!’ Izzy protests and Harry looks on the brink of tears.

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake. I’ll go out and get something.’