Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Author Nikki Moustaki certainly cannot resist the splendid lovebird, and her valentine to this irresistible avian wonder is the subject of this Complete Care Made Easy pet guide. This colorful guide offers vital information to both new and experienced bird keepers about this hookbilled parrot, covering all aspects of selecting, caring for, and maintaining well-behaved happy pet birds. Bird specialist and trainer Moustaki has written an ideal introductory pet guide about lovebirds with chapters on the history and characteristics of lovebirds, selection of a healthy, typical pet bird, housing and care, feeding, training, and health care. The chapter "A Look at Lovebird Species" gives readers a glimpse into all nine species. Although nine species exist--ranging from red faced to black collared lovebirds —only the peach-faced, black-masked, and Fischer's are widely available to pet owners. The selection chapter offers potential owners excellent advice about the three main species of lovebirds and how to select the best one from those available commercially. In the chapter on housing and care, the author discusses selection of the right cage, placement of the cage, and all the necessary accessories. A bird's diet is critical to its ongoing health, and the chapter devoted to feeding gives the reader all the info he or she needs about choosing a proper diet for the lovebird . The final two chapters of the book will be useful for bird fanciers interested in learning more about the breeding and the basic color variations and genetics of this beautiful small parrot. The book concludes with an appendix of bird societies, a glossary of terms, and a complete index.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 169

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Karla Austin, Business Operations Manager

Nick Clemente, Special Consultant

Barbara Kimmel, Managing Editor

Jarelle S. Stein, Editor

Jerry G. Walls, Technical Editor

Rose Gordon, Consulting Editor

Honey Winters, Designer

Indexed by Melody Englund

The lovebirds in this book are referred to as he or she in alternating chapters unless their gender is apparent from the activity discussed.

Photographs copyright © 2006 Eric Ilasenko. Photographs on pages 9, 46, 107, and 141 courtesy of Ellen [email protected]. Photograph on page 88 © 1995 PhotoDisc, Inc.

Text copyright © 2006 by I-5 Press™

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 Press™, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moustaki, Nikki, 1970-

Lovebirds : a guide to caring for your lovebird / by Nikki Moustaki ; photographs by Eric Ilasenko. p. cm. — (Complete care made easy)Includes index.ISBN 978-1-937049-30-01. Lovebirds. I. Title. II. Series.

SF473.L6M68 2006

636.6'864—dc22

2006010505

I-5 Press™

A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC™

3 Burroughs

Irvine, California 92618

Printed and bound in Singapore

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

Thanks to everyone at I-5 Press who worked on this book, especially my lovely and irrepressible editor, Jarelle Stein.

—Nikki Moustaki

Contents

1 The Splendid Lovebird

2 A Look at Lovebird Species

3 Selecting a Great Lovebird

4 Housing and Caring for Your Lovebird

5 Proper Feeding of Lovebirds

6 Training Your Lovebird

7 Keeping Your Lovebird Healthy

8 The Basics of Breeding Lovebirds

9 Lovebird Color Mutations

Appendix

Glossary

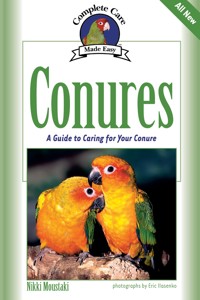

This is a pair of peach-faced lovebirds, one of the most popular species available today.

THE FRENCH CALL THESE BIRDSLESINSÉPARABLES—THE inseparables. Their genus name is Agapornis, which stems from the Greek agape, meaning “love,” and the Greek ornis, meaning “bird.” To the average person, they are lovebirds, a name that conjures images of affectionate birds sitting side by side on a swing, their heads together, calm and sweet. The romantic myth about lovebirds is that they will pine away and die if housed alone, and although this belief is incorrect, it shows how powerful our associations are with this small parrot. Lovebirds are wonderful pets, but they are also among the most aggressive and territorial of the commonly kept parrots. They are feisty to a fault, but they can also be incredibly sweet and loyal, making them great hands-on pets for the owner who has the patience to deal with a little bit of mischief.

What Is a Lovebird?

Lovebirds are small parrots. On average, they are about six inches long and have typical parrot features. They are acrobatic and active. The powerful beak is large in comparison with the head and is shaped like a hook (lovebirds are considered hookbills). The nostrils are barely visible in the narrow strip of naked skin at the base of the upper beak, known as the cere. Lovebirds have zygodactyl feet, which means that the feet are formed in an X shape, with two toes in front and two behind. This allows the bird to climb and hang as well as perch. Lovebirds waddle like ducks when walking on the ground instead of hopping, as other small birds do. The tail is short and bluntly rounded rather than long and tapered.

All but one species of lovebirds have large dark eyes that remain dark through adulthood. This blue black-masked lovebird also has a prominent white eye ring.

Lovebirds have large eyes that generally stay dark as the birds mature; juveniles in most parrot species are hatched with dark eyes that lighten as the birds mature. Of the nine species of lovebirds, only one, the rare Agapornis swindernianus, the black-collared lovebird, has a light eye—bright yellow—in the adult. Unlike other parrots, eye color can’t be used to help determine the age of a lovebird. However, immature birds typically have black lines and smudges on the beak for about three months, and their plumage colors are subdued compared with the brighter plumage of adults.

Unlike budgies and cockatiels, who are the only species in their genera, there are nine species of lovebirds in the genus Agapornis. Many of the species in the genus can interbreed, which shows how closely they are related, in contrast to budgies, who can’t successfully interbreed with any other species.

Lovebird History

The first lovebird known to Europeans was the red-faced lovebird. This bird was written about in the 1600s and was the first lovebird imported to Europe in the 1800s. The remaining eight species were discovered and imported to Europe over the next two hundred years, where they found their way into zoos and the pet trade. In particular, the peach-faced, the Fischer’s, and the masked lovebirds did particularly well in captivity.

Unfortunately, the remaining six of the nine species of lovebirds never became widely established in the fancy (hobby) as breeding birds. They either need special breeding conditions or don’t adapt well to caged conditions and the food being offered in captivity. Some are shy, such as the Madagascar lovebird, and don’t make the best hands-on pets.

The captive-bred lovebirds we have today resulted from the importation of wild birds from Africa, with nearly all of the species entering the market in Europe and eventually the United States in the early 1900s. Tens of thousands of lovebirds were exported from Africa each year, with many of the birds failing to adapt and dying as a result of capture. Some lovebirds, such as the Abyssinian and Nyasa, weren’t as abundant as the others within their very small habitats but were still prey for local trappers. In some cases, populations collapsed, and species of lovebirds went from abundant to rare in a matter of a decade or two. Today, some species, such as the Abyssinian and Nyasa, are likely to be found only in protected national parks and forests.

Discovering Lovebirds

EUROPEAN SCIENTISTS DISCOVERED THE NINE SPECIES of lovebirds more than two hundred years ago. The following list gives the nine scientific names of the lovebirds, the person who named them, the year they were first written about, and where they were first found.

Red-faced lovebird: Agapornis pullarius Linnaeus, 1758, probably Ghana

Madagascar or grey-headed lovebird: Agapornis canus Gmelin, 1788, Madagascar and Mauritius

Abyssinian lovebird: Agapornis taranta Stanley, 1814, Ethiopia

Peach-faced lovebird: Agapornis roseicollis Vieillot, 1818, Cape Province, South Africa

Black-collared lovebird: Agapornis swindernianus Kuhl, 1820, Liberia

Black-masked lovebird: Agapornis personata Reichenow, 1887, Tanzania

Fischer’s lovebird: Agapornis fischeri Reichenow, 1887, Tanzania

Nyasa lovebird: Agapornis lilianae Shelley, 1894, Malawi

Black-cheeked lovebird: Agapornis nigrigenis Sclater, 1906, Zambia

This is a young yellow black-masked lovebird; the head will darken as the bird matures.

The United States and many European countries passed restrictive laws against imported parrots in the 1970s and increased the restrictions again in the early 1990s. Today, few imported lovebirds are available legally in the United States. So there is no need to worry that buying lovebirds is harming the wild lovebird population somewhere in Africa. The lovebirds sold today were hatched and raised in captivity.

Lovebirds in the Wild

All nine lovebird species are found in mainland Africa except for one, the Madagascar lovebird (Agapornis canus), which is found on the large island of Madagascar off the southeastern coast of Africa. In general, lovebirds are flocking parrots of the open forests and grasslands of central Africa, extending from the western side of the continent (where they often are just isolated populations left over from when lovebirds were more generally distributed in the area) to near the Red Sea in the northeast and south to the area of the African Great Lakes (Victoria, Tanganyika, Malawi) in central Africa and to Namibia and Cape Province, South Africa, in the southwest.

A single green black-masked lovebird perches in a tree. In the wild, lovebirds tend to gather in small flocks.

Their Habitat

In the wild, lovebirds tend to spend the day in groups of five to twenty birds or more, resting and feeding in treetops. Lovebirds also feed on the ground—on grain crops and wild plants and grasses—and they can be a pest to farmers. They fly in fast spurts and are generally noisy when flying. Most mate for life but will take another mate if one is lost. In captivity, pairs also mate for life, but pairs in lovebird colonies have been known to have love affairs on the side.

Lovebirds prefer arid scrublands, savannas, and wooded grasslands close to the edges of cultivated land and never far from a reliable water source. Peach-faced lovebirds, the most commonly kept and bred species, have done very well in the wild in Arizona, where escaped pet birds have successfully created small flocks. They nest in cacti and feed on fruit and grasses, as well as in backyard bird feeders. I have seen small flocks of healthy-looking, feral peach-faced lovebirds feeding on the ground in South Florida.

Lovebirds prefer habitats near an abundant supply of water. At the edges of the African range, however, water can be scarce, and lovebirds in the southwestern and northeastern parts of Africa may be nomadic at times of the year when drought dries up nearby streams and ponds. Nomadic flocks are especially likely to feed on cultivated crops.

Some lovebirds—such as the Abyssinian lovebird—live at elevated ranges that get quite cool; these birds require a diet higher in fat than do others who live in more temperate climates. The Abyssinian and the Madagascar lovebirds also feed on wild figs, and the black-collared lovebird feeds nearly exclusively on figs.

Their Feeding Places

Lovebirds generally forage in the heads of bushes and trees, and they also come to the ground for grass seeds and planted crops, such as millet, rice, sesame, and corn. They feed in small flocks, but in some cases more than two hundred lovebirds have been seen descending on an especially fertile feeding ground. Where they have learned to raid crops, they are treated as pests and killed, although they are not nearly as destructive as many of the larger parrots.

Their Breeding Places

Although lovebirds roost (sleep and rest) communally, they break off from the flock into pairs to breed. The eye-ring lovebirds tend to nest communally, but other species are solitary and become intolerant of other birds who venture too close to where they are nesting.

Lovebirds create their nests using several different methods, depending on the species. Some find a deep tree hole (often an abandoned woodpecker or barbet hole) and line the bottom with a compact pad of leaves, bark, and grasses, as well as feathers. In most cases, it appears that the female does most of the nest-making and choosing of the site. Several species take over the large woven nests of weaver finches (which in Africa occur by the dozens in large trees) and lay their eggs there with no further preparation. Sometimes lovebirds add plant matter to existing holes in trees, crevices in cliff faces, and even holes in old buildings. The red-faced lovebirds build their nests inside arboreal termite mounds—the temperature inside the mound is warm and fairly constant, allowing the hen to leave her eggs to feed while they are incubating. (See chapter 8 for more detail on the breeding patterns of lovebirds.)

Lovebirds as Pets

Many pet shops carry three popular species of lovebirds: peach-faced (the most popular), Fischer’s, and black-masked. The other species are either hard to find, rare, or unavailable. A great many lovebirds sold today are color mutations of the normal color—or nominate—bird and bear little resemblance to the wild colors of their species.

This is an orange-faced mutation of the green variety of peach-faced lovebirds.

As long as you give your feathered companion plenty of attention, she won’t miss the company of another bird.

It is a common belief that lovebirds have to be kept in pairs in order to survive. This isn’t the case. A single lovebird with an attentive, loving human friend is thrilled to be part of that odd couple. However, a lovebird who is going to spend a great deal of time alone with no hands-on attention from a human companion should probably have another lovebird as a friend and cage mate.

Although lovebirds are common pet birds and sell for generally moderate prices, depending on the species and the mutation, it is difficult to recommend them as pets for children or for someone not very experienced with birds. The primary reason is that they can often be quite aggressive—both to other birds and to their owners. A lovebird’s beak is sharp and powerful, and this bird is not afraid to use it. However, that warning aside, lovebirds can also be incredibly loyal and sweet, wanting nothing more than to hang out with their human best friend, preening your hair and crawling inside your clothing. They are playful and active but often are content to sit on your shoulder and take a nap while you watch TV.

The Fischer’s lovebird is one of the three most common species of pet lovebirds. This is an unusual blue mutation.

THE NINE SPECIES OF LOVEBIRDS ARE QUITE DISTINCT, even though some of them look similar. Some are very common in captivity, and some aren’t suitable for captivity at all. A few species are very easy to come by, but most are very rare and not readily available for purchase. People who want to breed these rare lovebirds often enter into a consortium to bring them from overseas, which takes considerable time and effort. This chapter takes a close look at each of the lovebird species, both in the wild and as pets.

Common Species

The following three species of lovebirds are those most commonly found in captivity. They are the three you are likely to find in pet stores and are the most popular pet lovebirds.

The beautiful peach-faced lovebird is a popular pet. Peachies are also friendly and entertaining clowns.

Peach-Faced Lovebird (Agapornis roseicollis)

The most common lovebird in captivity today, the peach-faced lovebird represents the ideal lovebird to many beginners. Most peach-faced lovebirds are between six and seven inches long, and the relatively heavy build is reflected in a weight that may exceed two ounces, even in wild birds. Thousands of these lovebirds are bred each year for pet shop sales, and the species comes in perhaps more color variations (mutations) than any parrot except the budgie.

These are beautiful birds by any standard. In both sexes (which are not readily distinguished in this monomorphic species), the body is bright green and the lower rump and feathers above the tail are bright blue. The primaries of the wings are green with black toward the tips, and the tail has only traces of the black band found in most other species, along with some red and blue. However, the upper parts of the outer tail feathers often are bright red above and below. The entire face is reddish, with a broad bright red band running from the middle of the crown to the base of the beak and the top of the eye. The cheeks, throat, and upper chest are paler pinkish red (peachy), fading into the green of the belly. There is a very narrow white eye ring, the beak is yellowish white (horn colored), and the eyes are dark brown—nearly black—in adults. Peach-faced lovebirds are not in the eye-ring category, but their slight eye ring often categorizes them as intermediate. Juveniles have just a touch of pinkish red over the front of the face and the throat as well as black smudges on the beak, which disappear as the birds mature. They reach full coloration after the first molt—at about six to eight months.

This species prefers dry grasslands, shrubby savannas, and open woods. The birds can be found in a narrow strip of southwestern Africa extending from Angola through Namibia into Cape Province, South Africa. This species comes in an astounding number of natural color mutations (see chapter 9) that breeders capitalize on by using selective breeding, that is, by putting different colors together to create babies of specific colors.

As a companion, the peach-faced lovebird is a wonderful choice, friendly and feisty, cuddly and clownish. Hand-fed peachies are as loyal as dogs as long as you handle them frequently. However, be aware that when left alone too often or when in breeding condition, females can revert to unfriendly behavior and become a hazard to handle. Males are generally docile and will maintain their friendliness if hand-fed and handled while young. This species is highly unlikely to talk, with only a few individuals ever learning to say a word or two.

This yellow black-masked juvenile shows the distinct white ring that gives eye-ring lovebirds their name.

The White Eye-Ring Lovebirds

FOUR OF THE SPECIES OF LOVEBIRDS ARE CLASSIFIED AS eye-ring lovebirds because of the characteristic fleshy white ring around the eye, called the periophthalmic ring. These birds are the masked, the black-cheeked, the Fischer’s, and the Nyasa. They are all smaller than the peach-faced at about four and one-half to five inches. They nest in colonies and have slightly overlapping natural ranges. They will hybridize (when two disparate species mate and have offspring) in the wild if introduced into new territories and can produce fertile offspring.

Fischer’s Lovebird (Agapornis fischeri)

The range of this eye-ring species includes areas just to the south of Lake Victoria, mostly in Tanzania, and perhaps including Burundi and Rwanda (where the bird may have been introduced), west of the range of the black-masked lovebird. There they were declining in numbers—possibly because of trapping for the pet market (local and international)—until recently, as a result of human intervention. These lovebirds have been introduced into cities in Tanzania and Kenya, and there they may interbreed with black-masked lovebirds, who also are introduced to that range.

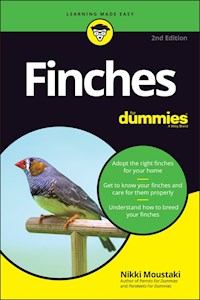

This young blue Fischer’s lovebird will make a wonderful companion and is a good choice for a first pet bird.

The Fischer’s is another truly beautiful little parrot, a little smaller than the peach-faced. The nominate birds have a green body with a yellowish green belly and a yellow to pinkish yellow breast that extends as a faint, broken band (a not-very-distinct yellow collar) onto the nape of the neck. The rump feathers are tinged with blue. The face is bright orange-red from the area above the beak to the throat and back to the eye and cheek (brighter above the beak), grading into brownish orange on the back of the head and the nape. Some birds appear to have the entire head pinkish red, especially when selectively bred in captivity. The beak is bright red in the normal and yellow birds, horn colored in the blue and white mutations.

The Fischer’s lovebird is common in pet shops and occurs in a few stunning mutations, including lutino (yellow), blue (white, light blue, and black), and albino (white). Some mutations are difficult to distinguish from the mutations of the black-masked, so it’s important to know what kind of bird you have before you begin breeding. Fischer’s lovebirds breed readily and are good lovebirds for beginners (just behind the peach-faced). They are just as feisty as the peach-faced, perhaps even a little more so, especially the females. This species needs a lot of hands-on attention to remain tame.

It’s easy to see how this black-masked lovebird got the name!

Black-Masked or Yellow-Collared Lovebird (Agapornis personata)