Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Story Machine

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

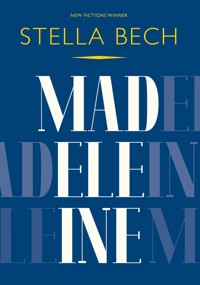

The debut novella by Stella Bech. Madeleine is everything Angela is not: charismatic, lovable, certain. A story of two people who find and lose each other, and the ways love, loss and memory shape a life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 62

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Madeleine

Stella Bech

Story Machine

Madeleine, Copyright © Stella Bech, 2021

Print ISBN: 9781912665068

Ebook ISBN: 9781912665075

Published by Story Machine, 130 Silver Road, Norwich, NR3 4TG; www.storymachines.co.uk

Stella Bech has asserted her right under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or copyright holder.

This publication is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Esther sent me a link just as I was going to bed.

Three girls of no more than twelve or thirteen years old formed a triangle. They took turns to come forward to outdo one another - the two behind cheering the one in front. The music was ours - the songs we’d used, years before. I watched a few videos and when I stopped to call her, I realised I was holding my breath.

‘I know,’ she laughed, ‘and they’re so much younger than we were. Can you imagine, if we’d had the internet?’

‘I can’t. It was traumatic enough as it was.’

‘We were never that good.’

I was defensive - of all three of us. ‘I don’t know, we were pretty great. We had heart like these three - for a while.’

‘You know I saw Madeleine a few weeks ago? She ignored me, of course, like I was a ghost. Less substantial than that, even. But I know she saw me.’

Esther hadn’t mentioned it at the time.

‘Are you sure it was her?’

‘Yes! You’ve forgotten how she is - she’s exactly the same now.’

I laughed then, but it wasn’t funny. ‘She might have been worried about what you’d say.’ The sound of Madeleine’s name from Esther’s mouth had planted something in me, a tightness that started in my gut and travelled upwards.

‘Oh no I doubt that. I probably just didn’t fit, with whatever her idea of herself is now. I’m sure none of it’s that conscious.’

We didn't talk for long. Esther was on her way to work in London, and it was late here. Unable to recover the present, I watched more videos. The whole operation was stronger than ours. It looked like there was money behind it: parents, management. But I knew how they felt. The adrenaline, the power, the compulsive danger of being so young, and good, and on the brink.

What kept me awake was Madeleine and the feeling she seemed to pull from me. A remorse that was almost maternal. I was surprised how rattled Esther was by the encounter with her, in ways she must have been years ago, too. Esther and I rarely talked about Madeleine - not then and not later either. But she was there, still. As I went over it, picturing the two women passing in the street in a country that used to be mine, something else reached me from miles and years away. It left again almost instantly, but for a second there it was like a pushed bruise. The old sensation of being nowhere near enough.

I can never remember meeting Madeleine, which is both odd, and, when I think about it, not at all.

The story has to start further back.

The headmistress of Glendale school threatens you when you say you want to leave. ‘You will fail.’ It is 1996. You are sixteen. Mrs Abram wears floral dresses draped across her large, oblong frame. Her head - always visible due to her height - stalks the school like a silverback gorilla’s - close-shaven, masculine, thuggish. Girls had to make an appointment to say it to her face: I want to leave. And it was unusual. You were on track for the best education there was. Esther said her meeting had been fine.

You can’t think of a response to what is a threat rather than a question, and her pedantic country accent seems to sew things up, so you grimace a dumb mixture of archness and shock and leave the meeting unsure if your resignation has even been accepted. The answer you’d rehearsed, that you and Esther discuss all the time - that you want to live in the real world as part of your education, with actual people of the opposite sex - had seemed too ridiculous to say in the room.

At the open evening the New School was so ‘new’ it was a disaster zone-like collection of leaking portacabins standing in for the collapsing tower of the main building - and it terrified you. Your real reason - that you must go because Esther is going; because you believe no-one can like you, and that all these sheltered little girls you’ve written off have hurt you; you want another chance - is too pathetic to admit to yourself.

In your final report Mrs Abram writes a personal note, which you read like a criminal. ‘Angela has been a wonderful student in every respect - a very special girl. We wish her every success and happiness.’

Had you been wonderful? Were you, special? A scholarship student, making up the numbers - and now bringing them down. So ungrateful. You feel sometimes ancient (like you’ve done things before, a million times), sometimes superhuman with possibility. But surrounding this, like a radioactive organ, throb billowing layers of blinding shame. You piece together identity from clues and fragments other people drop; shards of a broken mirror you bend to gather, furtive, after the event. At a party one of the boys says: ‘You could have anyone here, you know that don’t you?’

And yet nothing ever happens. You’ve never kissed anyone, never had a boyfriend. Only an idea that maybe after all this time trying to escape your age, you’ve overshot the mark - so that now you’re older than all of them, untouchable - post-sexual!

‘You can come off arrogant,’ your sister once told you. ‘It’s your face. So you have to make extra effort, you know?’

The effort is gratifying to other people, like a party trick - Oh my god Angie, she’s smart, but so dumb!! You watch as much as you can, developing a second sight, a third, hundreds, so that you can watch yourself at any moment in multicam. On the bus, listening to music and seeing the film of yourself as you perform it. Walking down the street, hearing catcalls and whistles a second before they come, like a sixth sense. The almost unbearable experience of walking into any full room, with its dozens of eyes.