Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

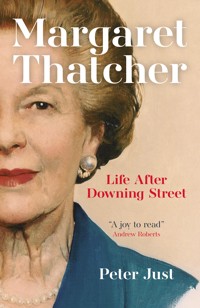

"A joy to read." Andrew Roberts The story of Margaret Thatcher's post-premiership years is a tale of high drama and low farce, with, at its heart, one extraordinary woman. Margaret Thatcher enjoyed perhaps one of the most consequential political afterlives in British history. No longer in office but never really out of power, she was not only one of the most impactful Prime Ministers the UK has ever had; she was also one of the most impactful former Prime Ministers the UK has ever had. British politics today undoubtedly reflects Thatcher's time in No. 10, but it is also shaped by her later life and how people reacted and still react to it. To mark the centenary of her birth, Margaret Thatcher: Life After Downing Street provides a radical reassessment of how Thatcher's premier emeritus years have been viewed to date. Covering the four main areas of her work after Downing Street – philosophy, party, policy and performance – and analysing her continued and continuing influence on the Conservative leaders and Prime Ministers of all parties who followed her, it demonstrates why, however small the politics may or may not have got since 1990, Margaret Thatcher is still big.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 511

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

iv

For my grandmother, Ivy Mary Just, with whom I used to discuss Margaret Thatcher, and for my father, Derrick Hugh Just, with whom I used to ‘debate’ her.

v

vi

Contents

Preface

The immediate genesis of this book was a paper I presented at a conference in the House of Lords in September 2023, organised by Professor The Lord Norton of Louth, the Centre for Legislative Studies and the Centre for British Politics. The conference was on Margaret Thatcher’s life, work and legacy. My presentation covered her time as a former Prime Minister following her resignation in 1990. It focused on her (after) life, (continuing) work and (emerging) legacy.1

The book’s gestation, however, has been much longer. My conference paper was based on postgraduate research I undertook under Lord Norton’s supervision at the University of Hull in the 1990s into what prime ministers do after they resign. That research had been inspired by my undergraduate dissertation on Margaret Thatcher and her ‘ism’ post-Downing Street.

As a northern, working-class child of the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher and Thatcherism, and people’s reactions to both, have been a significant feature of my life. Some of my earliest memories are of Lady Thatcher. One of these was the Conservatives’ victory in the 1983 general election. I can still recall getting up, going downstairs, picking up the newspaper, what was then the Daily Mirror, and seeing the news that Lady Thatcher would still be Prime Minister. Another memory is one of my uncles criticising Lady Thatcher to my paternal grandmother. This was about the poll tax. At the xconclusion of his diatribe, Grandma, then in her eighties, replied, ‘Well, she’s very clever.’ End of. This only added to my uncle’s irritation. Adding to a man’s irritation itself surely being a Margaret Thatcher kind of thing to do.

The day Lady Thatcher announced her resignation was the day of one of my mock A levels. I still remember the reaction of my politics teacher, Chris Robinson, when the news broke. I also remember seeing first hand the reaction that Lady Thatcher continued generating after No. 10. This was when I worked for Iain Dale at Politico’s, the Westminster bookshop, in the early 2000s. During the 2001 general election, our ‘Bring back Maggie’ badges sold out. We could not keep up with demand. That was certainly not the case for the badges of the then party leaders.

Then there were the occasions on which I met Lady Thatcher while working at Politico’s. First at a speech in her former constituency. We talked about how ‘exciting’ politics was – the former Prime Minister’s word, naturally. Then at a lunch event celebrating the portrait of Lady Thatcher by Richard Stone used on the cover of this book. She was wearing a blue coat dress. I wore a dark suit with purple shirt and purple tie. Waiting to be photographed with Lady Thatcher, I said to her, ‘I wish I had worn blue.’ Lady Thatcher looked at what I was wearing, looked at what she was wearing, and replied, ‘No, it wouldn’t have been quite right.’ The last time I met Lady Thatcher was the evening before the Queen Mother’s funeral. It was at a launch at the Savoy for her book, Statecraft. We talked about the statement she had issued, and the coverage it had and had not got.

When Lady Thatcher died, I was living and working in Rome. Walking down Via Ostiense, almost at Via del Porto Fluviale, I received a text message: ‘Margaret Thatcher non è più con noi.’ But, as xiwe will see, although Lady Thatcher was no longer with us, Margaret Thatcher was. She still is. Some may wonder if she will ever not be with us. Cue Sir Keir Starmer’s comments about her in late 2023, the reaction to them, and Starmer’s subsequent recantation. As Madam Deputy Speaker, Dame Eleanor Laing, said during Prime Minister’s Questions on 6 December 2023, ‘There is understandable excitement about the mention of the name.’2 Why excitement? And why understandable? This book helps to explain.

After Lady Thatcher’s death, the flag at the British Embassy flew at half-mast. A book of condolence was opened. The Cardinal Secretary of State, Tarcisio Bertone, sent a telegram on behalf of Pope Francis to David Cameron: ‘…the Holy Father invokes upon all whose lives she touched God’s abundant blessings’, it concluded. Lady Thatcher’s death had political aspects too. An Italian friend posted a photograph of her on Facebook. Their message read, ‘In Italia ci vorrebbero persone come Margaret … Forse così le cose andrebbero alla grande.’ (‘In Italy if we had people like Margaret … maybe things would be great.’)

Interestingly, entertainingly, or perhaps both, during my time in Rome, there were regular transport strikes. They always seemed to happen on a Friday. The only time they had any actual impact on my life was the Friday after Lady Thatcher died. Was it a sign? What was also interesting when I lived in Rome was that, after Queen Elizabeth II and Diana, Princess of Wales, the person Italians asked me about most often was Margaret Thatcher.

Given the nature of both my work and the Italians with whom I worked, our conversations invariably turned to politics. When they touched on Germany, I always commented, ‘You sound like Margaret Thatcher’ – as the Italians did when they talked about the single currency. There was a meme entitled ‘For those who xiihave forgotten…’ that frequently did the rounds. It featured photographs of Lady Thatcher and Romano Prodi, the former Italian Prime Minister. Lady Thatcher’s quote read: ‘The euro is a danger for democracy, it will be fatal for the poorest countries. It will devastate their economies.’ Prodi’s read, ‘With the euro we will work one day less, earning as if we worked one day more.’ No doubt you can guess which opinion the meme creator thought was the correct one.

After 1990, Lady Thatcher did more than just provide quotes for Italian memes. In addition to visiting the country, both for work and on holiday, she intervened in Italian politics – including by supporting Silvio Berlusconi in the 2001 election.3 She was also called in aid by various figures. Ahead of the 1994 election, Antonio Martino, a member of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, proposed a reform programme that was, he said, ‘more radical than that espoused by Margaret Thatcher in 1979.’4 After Forza Italia won the election, Lady Thatcher sent Martino congratulations. When he called to thank her, she gave him ‘her usual pep talk: “You must do for Italy what I did for Britain.”’ Martino explained why Italy was at a disadvantage compared to Britain. He then added, ‘However, we have something which you didn’t have.’ ‘What’s that?’ Lady Thatcher asked. Martino replied, ‘Your example.’5

Martino revealed another important part of Lady Thatcher’s life after 1990: simply being Margaret Thatcher. During a break at a conference in Fiesole, Tuscany, in 1991, he and Lady Thatcher were walking along the hotel’s portico. The countryside ‘looked magnificent’. Lady Thatcher said to Martino, ‘Yours is a beautiful country, with a rotten government.’ Martino replied, ‘My dear lady, the opposite would be much worse.’ At the conference, Lady Thatcher commented, ‘Civilisation is the exclusive prerogative of xiiiEnglish-speaking peoples.’ Martino was the only non-English, non-American person present. He looked at John O’Sullivan, who was sitting next to him. O’Sullivan smiled and said, ‘You have been consigned to barbarism!’

Lady Thatcher continued to be called in aid after her death, too. Following disturbances between Napoli and Eintracht Frankfurt fans in March 2023, the Napoli owner, Aurelio De Laurentiis, said, ‘Now politics must face the problem and I hope that [Prime Minister Giorgia] Meloni will do like the only prime minister who has had the courage: the English one, Margaret Thatcher.’6 Meloni has also been compared to Lady Thatcher, including by Rishi Sunak. In December 2023, he said, ‘I can only guess what first attracted Giorgia to the strong female leader who was prepared to challenge the consensus, take on stale thinking and revive her country both domestically and on the international stage.’7

This calling in aid and being compared to Lady Thatcher was a defining feature of her life after Downing Street. It was and is one of the hallmarks of and central reasons for her continued and continuing influence in British politics. As seen above, it did not just happen in the United Kingdom. It happened in other countries, too. Examples of this are detailed in files in the National Archives about Lady Thatcher’s post-prime ministerial travels. All this could be taken to demonstrate, adapting some words of President Macron’s about the Queen, that to us she was our Prime Minister, while to them she was The Prime Minister. How The Prime Minister lived her life, continued her work and witnessed her legacy emerge after Downing Street is the story this book tells.

It has been written largely during visits to Rome, which is fitting, for the Italian capital was the stage for one of Lady Thatcher’s most indelible post-prime ministerial appearances, certainly of her xivlast years. This was when she met Pope Benedict XVI in St Peter’s Square in May 2009. The image of the Pontiff and the Prime Minister was iconic. Naturally, it generated press coverage. But then, as we will see, what didn’t with Lady Thatcher after No. 10? The Daily Mail headlined the story: ‘Iron Lady grants the Pope an audience’.8

In his magisterial official biography of Lady Thatcher, Charles Moore writes movingly about this meeting and its aftermath. The anecdote highlights another aspect of Lady Thatcher’s life after Downing Street: performance. That too was, and is, central to her legacy, and to her continuing political relevance. The crowds in St Peter’s Square had recognised Lady Thatcher and were clapping. While heading to her car, someone told her that people wanted to photograph her. Having removed her mantilla and adjusted her hair, Lady Thatcher ‘gave a regal, all-embracing wave, to loud applause.’ Moore concluded, ‘She had performed brilliantly.’9

If not Lady Thatcher’s final public appearance, this was surely one of her last performances, however fleeting, on the world stage. That it should have been in Rome is also fitting. For if all roads lead there, as this book shows, then Lady Thatcher’s premiership was the starting point from which all subsequent premierships began. In large part that was due to her post-premiership, and to how, after 1990, people responded and continue to respond to Margaret Thatcher’s life after Downing Street.

259Notes

1 See Peter Just, ‘“I Am Big, It’s the Politics That Got Small”: Margaret Thatcher’s premier emeritus years: her (after) life, (continuing) work, and (emerging) legacy’, in Philip Norton and Matt Beech (eds), The Companion to Margaret Thatcher (London: Edward Elgar, forthcoming 2025).

2https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-12-06/debates/E100CDC2-009D-4161-9443-38833C8DC25B/Engagements

3 Richard Owen and Andrew Pierce, ‘Thatcher throws weight behind Berlusconi’, The Times, 12 May 2001.

4 Tom Rhodes, ‘Berlusconi’s man prepares Thatcher medicine for Italy’, The Times, 23 March 1994.

5https://www.heritage.org/conservatism/report/what-we-can-learn-margaret-thatcher

6 Neil McLeman, ‘Napoli owner makes Margaret Thatcher appeal after “thugs” hold Italian city hostage’, Daily Mirror, 16 March 2023.

7 Dominic McGrath, ‘Rishi Sunak warns migrants could “overwhelm” countries in Rome speech’, www.breakingnews.ie, 16 December 2023.

8 ‘Iron Lady grants the Pope an audience’, Daily Mail, 28 May 2009.

9 Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Three: Herself Alone (London: Allen Lane, 2019), p.838.

Introduction

Margaret Thatcher concluded the first volume of her memoirs, The Downing Street Years, with the following sentence:

I waved and got into the car with Denis beside me, as he has always been; and the car took us past press, policemen and the tall black gates of Downing Street, away from red boxes and parliamentary questions, summits and party conferences, budgets and communiqués, situation rooms and scrambler telephones, out to whatever the future held.1

What did the future hold for Lady Thatcher2 as she embarked on her new life as a premier emeritus, a former Prime Minister who no longer holds any ministerial or party office?

Some may be forgiven for thinking that Lady Thatcher did not have much of a future at all. Indeed, Caroline Slocock wrote that her life seemed to ‘fall apart when she left No. 10’.3 Books about her have tended not to devote much space to her life after Downing Street. Just 15 per cent of the final volume of Charles Moore’s official biography was about Lady Thatcher’s post-1990 life, covering ‘The lioness in winter’, ‘Stateswoman – and subversive’, and ‘The light fades’. Other biographies, such as those by Robin Harris, Jonathan Aitken and John Campbell, have followed a similar pattern.

Reviewing Harris’ book in 2013, Andy Beckett wrote of ‘the xviempty, sad quarter of a century that unfurled for her’ after 1990.4 That quote encapsulates the general, largely negative, view of Lady Thatcher’s post-premiership. Indeed, a participant at the Margaret Thatcher life, work and legacy conference in September 2023 described it as ‘a failure’. In 2005, Andrew Roberts said that her post1990 career had been ‘almost unbearably poignant and frustrating’.5 Charles Moore wrote that while her interventions in UK politics after 1990 were ‘usually right in principle’, they were ‘sometimes ill-judged in practice’.6 ‘I don’t think she’s had anything useful to do,’ Sir Bernard Ingham said in 1999, and spoke of a ‘singularly empty existence’ compared to her time as Prime Minister.7

That said, in the same article as Ingham’s comments, Lady Thatcher’s private secretary, Mark Worthington, spoke of her being in the office every day. She had a huge overseas travelling schedule, visiting the United States five or six times a year, and the Far East almost the same amount. ‘There is an awful lot of preparation for her speeches and she is in continual meetings with people from here and overseas,’ Worthington commented.

So, there clearly was a life for Lady Thatcher after 1990. To date, it has been under-researched and largely misunderstood, if not actively misrepresented. As a result, its long-term effect has not been fully appreciated. This book, the first full-length examination of Margaret Thatcher’s life as a former Prime Minister, attempts to rectify that.

Making extensive use of material from the National Archives, the testimony of key players and more detached observers, as well as contemporary media reports and material from the Margaret Thatcher Foundation, we show that rather than having an ‘empty, sad quarter of a century’, Lady Thatcher in fact had a full life, filled with incident, at least up to 2002. Her time from then until her xviideath in 2013 was characterised by appearances, silent but present, ever less physically, and seemingly ever more psychologically.

Beyond that, we also reveal the long-term, continued and continuing impact of Lady Thatcher’s post-prime ministership. Without a proper understanding of Lady Thatcher’s ex-premiership and, perhaps most of all, people’s reaction to it, it is impossible to understand British politics today. That is why, while Lady Thatcher’s last quarter of a century could not compare with the one preceding it, it is worthy of study.

At the outset, it is important to note the context of Lady Thatcher’s life after Downing Street.

First, the amount of material about it is vast. It might not be too much of an exaggeration to say that, before Lady Thatcher, never in the field of the ex-premiership had so much been written about one former Prime Minister over such a long period of time in such depth.

Masses of newspaper articles about Lady Thatcher after 1990 have been published, up to and including today. For all her mastery of detail, Lady Thatcher was also always a headline type of person, and she continued generating them long after her departure from Downing Street – long after her death, even. Two of Lady Thatcher’s books, The Path to Power (1995) and Statecraft (2002), provide rich material. So do the books that have been written about her. Other political actors’ biographies, autobiographies and diaries also contain information about her premier emeritus years. There are also recordings of Lady Thatcher after 1990, including speeches, interviews, Q&As and footage of her campaigning in general elections, many of which are available online,8 as well as the observations of participants and other witnesses, some captured in documentaries, some in academic interviews.xviii

Then there are the archives – specifically material held in the National Archives. The Prime Minister’s Office records largely deal with Lady Thatcher’s role in UK politics after 1990 and provide insight into her relationships and interactions with John Major and Tony Blair. Foreign Office records detail Lady Thatcher’s travels abroad as a former Prime Minister and tell us more about her global role, the impact and influence she had in the countries she visited. They also show how what Lady Thatcher said and did in those countries could have an effect back in the UK. As well as the archives of other countries, and other individuals, there is Lady Thatcher’s own archive: the Margaret Thatcher Foundation website provides substantial information about her post-premiership. It is both an invaluable resource for any student of Margaret Thatcher and a remarkable achievement. This is largely due to the site being run – as Sir Julian Seymour, the director of Lady Thatcher’s office, noted – ‘to the highest scholastic standards’ by Christopher Collins. As for Lady Thatcher’s private papers, Seymour noted her ‘generosity’ in donating them to Churchill College in Cambridge.9 While the extensive papers relating to her life after Downing Street are closed, the Margaret Thatcher Archive Trust is currently focused on strategies to provide access to them. Andrew Riley, the archivist of Lady Thatcher’s papers, has said that this will be a major project. He estimates there will be many hundreds of thousands of pages to process.10

It is, therefore, important to note that our understanding of former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher may develop further over time as more material becomes available and, given the amount of currently available material, what follows is not an account of everything Lady Thatcher did after Downing Street, but a sketch of just some of it.xix

When writing that story, it is necessary always to distinguish between Margaret Thatcher the person and Margaret Thatcher the persona. After 1990, we learnt more about both. With regard to the latter, the character that was Margaret Thatcher, and the way Lady Thatcher played her after Downing Street, was crucial to her legacy. It helps to explain why, in her centenary year, she persists in British political consciousness, arguably as potent now as an idea as she was as a person between 1979 and 1990.

We must also recognise that, as important as what Lady Thatcher did after No. 10 was the way she did it. Speaking in 2000, a member of the shadow Cabinet said, ‘There’s as much showbusiness as ideology in her performance.’11 At times after 1990, people could be forgiven for thinking they were witnessing a production of Carry On Maggie.

It must be stressed, however, that when Lady Thatcher was playing the character that was Margaret Thatcher, she was true to herself. Her performance was authentic and was played with conviction. The character that was Margaret Thatcher was simply the dramatic persona that gave voice to Margaret Thatcher’s beliefs and illuminated her character. As Chris Patten wrote, ‘One of Margaret Thatcher’s commendable virtues, though it rattles the chandeliers in chancelleries and embassies the world over, is always to be herself.’12

As is the case with most subjects, nuance is required when examining Lady Thatcher’s post-prime ministership, a requirement also stressed by Sir Julian Seymour.13 This is especially the case with Margaret Thatcher the person, though less so with Margaret Thatcher the persona. As with her premiership, there is a danger of viewing Lady Thatcher’s life after 1990 through the prism of what she and what others said she did, rather than what she actually did and did not do. If she was a more nuanced Prime Minister than xxmany, including herself, might claim, she was also a more nuanced ex-premier than has been appreciated.

Lady Thatcher’s years as a former Prime Minister fall into two distinct, but connected, phases, which are of almost equal length. The first, from 1990 until 2002, we call the ‘siren’ years. The second, from 2002 until Lady Thatcher’s death, are the ‘symbol’ years. During the former, Lady Thatcher’s active political work took place, while in the latter, she demonstrated that you do not always need to speak in order to communicate.

Lady Thatcher’s life after office is the story of ‘a powerful personality now operating in more adverse conditions.’14 After 1990, Lady Thatcher’s life was about attempts at influence, rather than the making of decisions. We see her trying to make a difference; and we see her navigating, or perhaps ignoring or not recognising, the difficulties and challenges of doing so.

That said, Lady Thatcher’s post-Downing Street life is as much about others’ – mainly men’s – reactions to her as it is about herself. As Moore wrote, ‘The effect on others of her extraordinary personality, made greater by the fact that she was a woman operating in a world of men, is often the story itself.’15

The post-prime ministerial effect of Lady Thatcher’s personality on others is clear from the observations of many of her political contemporaries. Her personality had a wider effect, too, after Downing Street, including on non-political contemporaries and across the globe. This is revealed in files released by the National Archives since her death. These records, especially those about her post-prime ministerial travels, pulsate with Lady Thatcher’s personality and the reaction it, and sometimes the reaction her name alone, excited in others, both in anticipation and in actuality. The use of exclamation marks in the files is telling, as are handwritten comments on formal documents.xxi

If her being a woman is key to understanding Lady Thatcher’s premiership, it is also key to understanding her post-premiership. Throughout her time as a former Prime Minister, Lady Thatcher spoke about being a woman. She also faced (or perhaps more accurately, she continued to face) certain judgements because she was a woman. Long after Lady Thatcher’s resignation, one of her Cabinet ministers, reflecting on her behaviour towards Geoffrey Howe, commented, ‘She spoke to Geoffrey like no man should be spoken to by a woman.’

Not unrelated to that, men seemed even less sure how to respond to Lady Thatcher after Downing Street than they did before. Indeed, it might be argued that Lady Thatcher spent her premier emeritus years winding men up. Or, rather, men spent Lady Thatcher’s premier emeritus years being – and allowing themselves to be – wound up by her.

‘Irritating’, ‘irritated’ and ‘irritation’ are words that run through much of the commentary, at least the contemporary commentary up to 2002. Some (men) probably felt that, after 1990, Lady Thatcher became the most irritating person in British political history, if she was not already. She may have taken this as a badge of honour. Launching her Collected Speeches at Hatchards bookshop in 1997, she spoke of ‘speeches delivered to barely disguised fury since leaving office’, adding: ‘And just so no-one gets any wrong ideas: be warned – I intend to keep on talking!’16 We can almost hear the (subversive) pleasure in her voice, can’t we? What might have added to the irritation, and to Lady Thatcher’s pleasure, is that, as she no doubt would have argued, events generally turned out to prove her right – and the men wrong.

Finally, as with almost everything else to do with Margaret Thatcher, her premier emeritus years are contested and full of myth, xxiithough given her personality, and others’ reactions to it, how could it be otherwise?

Judgements about both the myth and reality of Lady Thatcher’s (after Downing Street) life, (continuing) work and (emerging) legacy have varied, but have often been coloured by three things: first, how the people making them think former prime ministers in general do and should behave – and how they think this former Prime Minister should have behaved – rather than how premiers emeritus have historically behaved and do behave;17 second, people’s views of how Lady Thatcher compares as a premier emeritus to other former prime ministers; and third, what might be called the effect of Lady Thatcher as a premier emeritus.

We will, therefore, conclude by assessing these existing judgements about Margaret Thatcher’s life after No. 10. By doing so, we will determine whether they remain valid or whether it is time for fresh perspectives on her premier emeritus years – perspectives that tell us something new about former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and that require us to reframe how, to date, we have seen her life after Downing Street.

Notes

1 Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: HarperCollins, 1993), p.862.

2 We use Lady Thatcher throughout, rather than using Mrs Thatcher for 1990–92 and then Lady Thatcher from 1992 onwards.

3 Caroline Slocock, People Like Us: Margaret Thatcher and Me (London: Biteback, 2018), p.328.

4 Andy Beckett, Margaret Thatcher by Charles Moore; Not for Turning by Robin Harris, The Guardian, 24 April 2013.

5 Andrew Roberts, ‘Happy birthday to a fearless Iron Lady’, Daily Express, 13 October 2005.

6 Charles Moore, ‘The mellowing of Margaret Thatcher’, Daily Telegraph, 12 October 2005. Accessible at Thatcher MSS (digital collection), 110596. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110596

7http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/special_report/1999/04/99/thatcher_anniversary/325148.stm

8 See, for instance, https://www.youtube.com/user/thatcheritescot, https://x.com/realmrsthatcher, https://x.com/simplysimontfa and https://www.instagram.com/the_grocersdaughter/

9 Conversation with Sir Julian Seymour, 13 March 2025.

10 Andrew Riley, correspondence with author, 23 October 2023 and 22 January 2024.

11 Matthew d’Ancona, ‘Is it really ten years?’, Sunday Telegraph, 19 November 2000.

12 Chris Patten, East and West (London: Pan Books, 1999), p.289.260

13 Conversation with Sir Julian Seymour, 13 March 2025.

14 Moore, op. cit., p. xvii.

15 Ibid., p. xv.

16 Thatcher MSS (digital collection), 109302. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/109302

17 For an example of where myth and reality about premiers emeritus differ (at least in relation to their parliamentary activity), see Peter Just, Ex-Prime Ministers and Parliament: A Riposte to Mythology, Research Papers in Legislative Studies, 1996. See also Peter Just, ‘Former PMs as “double agents”’, The Times, 10 September 1999.

Part I

Margaret Thatcher’s (after) life

Like all ex-premiers, Margaret Thatcher lived three lives after No. 10: private, public and political. From each of these lives, we learn more about both the character of and the character that was Margaret Thatcher.

While the whole of Lady Thatcher’s life after Downing Street is under-researched, this is especially so when it comes to her private and public lives during this period. Studying them, however, is crucial. To adapt Walter Bagehot’s phrase, while in her political life we witness Lady Thatcher attempting to be efficient, in her private and public lives we see her being dignified. This provides often overlooked insight into Margaret Thatcher the person and Margaret Thatcher the persona.

More importantly for our purposes, elements of Lady Thatcher’s private and public lives also contributed to her continued and continuing political significance. They generated reactions in others. They excited media coverage. They kept her in the public eye. They, on occasion, had contemporary political impact. They helped Lady Thatcher burnish what Charles Powell has described as her ‘deliberately cultivated image of battling Maggie’.1 And all of this was 2to have consequences for Lady Thatcher’s (emerging) legacy, as was her political life after Downing Street. About that, as we shall argue, existing views need to be revisited. That is so we can better understand both what happened after Lady Thatcher resigned, and why even today she continues to have political relevance.

Notes

1 Charles Powell, ‘She carried an aura of excitement with her … the atmosphere was charged’, Sunday Telegraph, 14 April 2013.

Chapter One

Private life

As with every aspect of Margaret Thatcher’s life after Downing Street, her private life had political significance. Sometimes this was purely contemporary, impacting on the politics of the day, and sometimes it had a longer-term effect, affecting how Lady Thatcher was, and is, viewed.

Family

As a family, the Thatchers provided good copy. For better or worse, throughout her premier emeritus years, Lady Thatcher’s relations found themselves in print or on television, and even, on occasion, in files now held in the National Archives.

Sometimes this played up to the character that was Margaret Thatcher. After Carol Thatcher’s victory in I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! in 2005, Lady Thatcher said she was ‘immeasurably proud’ and ‘absolutely thrilled to bits’ to see her daughter win. Carol had displayed ‘True Thatcher spirit’1 – this, no doubt, being both the spirit of ‘battling Maggie’ and a winner.

As for Lady Thatcher’s son, Mark Thatcher, at times he played a controversial role in her life after 1990. As will be seen in Chapter Five, this included the 1994 Conservative Party conference, where his business dealings overshadowed her attendance. Her son’s activities could also have political consequences for the government, and were sometimes raised in Parliament.2

4Sometimes Mark’s involvement in Lady Thatcher’s overseas trips caused issues for her office, and for officials in the UK and the countries she was visiting, either because of his role in organising them or because he accompanied Lady Thatcher when she visited. An FCO telegram to Britain’s ambassador to China towards the end of August 1991 highlights examples of this regarding her September 1991 visit. The telegram concludes, ‘Clearly much of the above is extremely sensitive.’3 In September 1991, the high commissioner to Brunei, Adrian Sindall, reported that Mark Thatcher had arrived some days before his mother, noting that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had ‘smartly sent him down to the High Commission to see me.’4 In 1992, the British ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, Sir Graham Burton, reported Mark Thatcher arriving and being ‘instantly into the role of Private Secretary and programme checking and amending.’5

As well as controversy, coverage of Mark Thatcher could also generate sympathy for Lady Thatcher. In March 1995, John Major wrote inviting Lady Thatcher to a seventieth birthday dinner at Downing Street later that year. Referring to the continued scrutiny of her son’s activities, Major commented on how upsetting it must be for her and reflected on similar treatment of his own son’s private life.6

Sometimes Lady Thatcher’s family found itself in the media because she talked about it in pieces with wider political content, and this was the case in a June 1991 Vanity Fair profile by Maureen Orth7 and an August 1998 interview with SAGA Magazine.8

Health

If Lady Thatcher’s family life became, or remained, political after 1990, so did her health.

5Extensive coverage greeted the announcement on 22 March 2002 that Lady Thatcher was giving up public speaking following a series of small strokes.9 Much of this was obituary-style in content and tone. The cover of Private Eye’s 5–18 April edition was headlined ‘Thatcher shock’10 and featured an empty speech bubble coming out of her mouth.

From 2002 on, bouts of ill-health were reported in the press, both broadsheet and tabloid. On occasion this too was obituary-like in content and tone. Coverage of Lady Thatcher’s arrivals home and departures from hospital – her ‘entrances and exits’ – gave a nod to her career. All this contributed to what we might call the iconography of illness, and it played up to and helped to cement a particular image of Lady Thatcher in our political consciousness. Even in a medical context, the character that was Margaret Thatcher took centre stage.

In March 2008, for example, there was significant coverage of Lady Thatcher leaving hospital. The Sunday People spoke of ‘Maggie OUT!’,11 the Sunday Telegraph ran with ‘The lady returns to health’,12 and the Sunday Mirror ‘Maggie Maggie Maggie, Out Out Out of hospital’.13 A News of the World leader,‘An Iron constitution’, reflected that although Lady Thatcher may be frail, ‘she still has more steel than the rest of us’,14 while the Sunday Telegraph opined that she had ‘proved herself indomitable once more, making a characteristically regal exit’. It spoke of her taking ‘as commanding a place in the spotlight as she ever has.’15

In June 2009, Lady Thatcher had a shoulder operation. When she returned home, she wanted to talk to a group of journalists outside her house. She was persuaded by her aides not to do so, with Andrew Pierce reporting one saying, ‘You know what Lady T is like. She would have told the reporters not to make a fuss about 6her and would have demanded to know from them what has been going on in the real world while she has been in hospital.’16

In 2010, illness forced Lady Thatcher to miss her eighty-fifth birthday reception at Downing Street. She sent a statement to be read out, ‘I hope that you will appreciate that on this particular occasion I have had to accept that the Lady is not for returning.’17

When Lady Thatcher left hospital, it was front-page news in the Daily Telegraph under the headline, ‘The Iron Lady returns home’.18 Directly below The Sun’s story was an article revealing that Tony Blair had donated £27,000 towards David Miliband’s leadership bid.19 On the same day as Lady Thatcher left hospital, Gordon Brown delivered his first speech in the House of Commons since resigning as Prime Minister.20 Yet, of the three ex-premiers, it was Lady Thatcher who still seemed the most newsworthy, almost twenty years after her resignation.

When overtaken by illness, both Lady Thatcher herself and people’s reactions to her tended to reinforce the Margaret Thatcher persona. She seemingly went on and on despite her ill-health, giving the impression of having taken to heart Winston Churchill’s injunction to ‘never surrender’. In October 2022, Henry Kissinger commented, ‘I continued to call on her on every trip to London, even in the years after illness had clouded her mind. During our final meetings, I saw a leader who had faced down life’s trials with courage and grace.’21

Speaking after her death, Ed Miliband said, ‘As a person, nothing became her so much as the manner of her final years’. Speaking of Lady Thatcher’s ‘utmost dignity and courage’, he said he would always ‘remember seeing her at the Cenotaph in frail health but determined to pay her respect to our troops and do her duty by her country.’22

7The wider context of what was and was not known about Lady Thatcher’s health in her siren years should be noted. By the twenty-first century, Lady Thatcher’s mental powers were in decline, but when the decline had started was disputed.23

It is difficult to judge, therefore, to what extent, if any, Lady Thatcher’s health affected her (continuing) work, at least until 2002. Writing in 2005, John Sergeant said he thought ‘it would be a mistake to believe that declining health was a factor in her approach to important issues.’24 We share that view.8

Notes

1 Elisa Roche, ‘Thatcher on Thatcher’, Daily Express, 7 December 2005.

2 See, for instance, the National Archives’ website: Discovery: PREM 19/4603, DEFENCE. Allegations against Mark Thatcher: Al Yamamah and others, 30 September 1994–10 November 1994, available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16854818.

3 The National Archives, FCO 21/4831, Visit by Margaret Thatcher, former UK Prime Minister, to China, September 1991, 1 January 1991–31 December 1991, f3.

4 Ibid., f23.

5 The National Archives, FCO 8/8754, Visit by Margaret Thatcher, former Prime Minister, to the Gulf states, April–May 1992, 1 January 1992–31 December 1992, f28.

6 The National Archives’ Website: Discovery: PREM 19/6222, FORMER PRIME MINISTERS. Lady Thatcher: part 2, 12 May 1993–17 March 1997, available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C17326255

7 Maureen Orth, ‘Maggie’s Big Problem’, Vanity Fair, June 1991.

8 Douglas Keay, ‘My children have to live their lives. I took a different life’, Daily Telegraph, 28 August 1998.

9 Thatcher MSS (digital collection), 109305. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/109305

10https://www.private-eye.co.uk/covers/cover-1051

11 Tom Carlin, ‘Maggie OUT!’, Sunday People, 9 March 2008.

12 Andrew Alderson, ‘The Lady Returns to Health’, Sunday Telegraph, 9 March 2008.

13 ‘Maggie Maggie Maggie, Out Out Out of hospital’, Sunday Mirror, 9 March 2008.

14 ‘An Iron constitution’, News of the World, 9 March 2008.

15 ‘To her health’, Sunday Telegraph, 9 March 2008.

16 Andrew Pierce, ‘On the mend’, Daily Telegraph, 30 June 2009.

17 Chris Smyth, ‘Thatcher is admitted to hospital with flu infection’, The Times, 20 October 2010.

18 ‘The Iron Lady returns home’, Daily Telegraph, 2 November 2010.

19 Kevin Schofield, ‘Maggie is out of hospital’, The Sun, 2 November 2010.

20https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2010-11-01/debates/1011025000002/AircraftCarriers#contribution-1011025000633

21 Henry Kissinger, ‘Why there was only one Iron Lady’, Mail on Sunday, 22 October 2022.

22https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2013-04-10/debates/1304104000001/TributesToBaronessThatcher

23 Moore, op. cit., p.829.

24 John Sergeant, Maggie: Her Fatal Legacy (London: Macmillan, 2005), p.363.

Chapter Two

Public life

In June 2007, Tony Blair was asked what he would be when he resigned as Prime Minister. When ‘ex-politician’ was suggested, Blair replied, perhaps tellingly,‘No, I’ll be a former celebrity.’1 While Lady Thatcher was not a ‘former’ type of person, she did acquire celebrity status after Downing Street. As Matthew Parris wrote, ‘as a famous personality she became a source of national entertainment.’2 While this may have started before 1990, it intensified afterwards.

Lady Thatcher’s post-office public life involved formal state and public occasions, as well as attending, and sometimes taking part in, less formal events. Sometimes, Lady Thatcher’s comments at functions found their way into the press. For example, at the launch of Sir Bernard Ingham’s The Wages of Spin in March 2003, Lady Thatcher placed her finger over the ‘p’ in the word ‘spin’ on the front cover. ‘It’s amazing they ever put that letter in,’3 she observed ‘witheringly’.

As this anecdote illustrates, Lady Thatcher’s public appearances revealed more about her character, and we also saw her performing the character that was Margaret Thatcher. As with her private life, coverage of Lady Thatcher’s public life kept her in the public eye and tended to reinforce the ‘battling Maggie’ image, which shaped how people viewed and continue to view her. Equally, Lady Thatcher’s public life also had political consequence, both contemporary 10and longer-term. The dignified aspects of Lady Thatcher’s life supported the efficient.

This could be seen in the judgements that continued to be made about Lady Thatcher’s appearance. Much of the commentary about her after 1990, particularly by sketch writers, referenced how she looked and what she wore. Lady Thatcher would not necessarily have disapproved of this, since, as Charles Moore wrote in 2005, ‘She dresses and makes up and has her hair done with the greatest elegance and care. She is dignified and beautiful, believing that she must look her best. It has always been an iron law with her that she must not let people down, and she obeys it still.’4

Although it was the case that she experienced this judgement because she was a woman, nevertheless, Lady Thatcher’s appearance gave her a visual advantage over her male colleagues in getting her message across on television and in photographs used in newspapers and magazines.

Throughout her time as a premier emeritus, Lady Thatcher’s wardrobe featured in the media. In January 2000, the Daily Telegraph’s fashion editor, Hilary Alexander, noted that she was ‘emerging as the year’s most unlikely fashion icon.’5 In May 2004, The Times’ fashion editor, Lisa Armstrong, wrote of ‘the Maggie look’.6 That November, the American fashion designer Marc Jacobs was reported as saying, ‘This season is all about finding the Margaret Thatcher look sexy.’7 After her death, reflecting on Lady Thatcher’s prime ministerial attire, Vicki Woods wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph headlined ‘Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady, used her wardrobe as a weapon’.8 Arguably, she used it in the same way after 1990. She consistently looked the part and was always dressed for impact.

This was seen most clearly at funerals and memorial services. In 11his nineties, Harold Macmillan described the latter as the ‘cocktail parties of the geriatric set’,9 and Lady Thatcher was assiduous at attending these, going to over 100 after Downing Street. At such events, biographer Charles Moore notes, she ‘cut a striking figure, carefully and formally dressed, wearing elegant hats’.10

Lady Thatcher was at her most striking at Sir Denis Thatcher’s funeral and memorial service. At both, iconic photographs of her were taken, capturing what might be called the look of loss, constituting some of the most arresting images of her after 1990.

Those services aside, Lady Thatcher’s most important attendance at the ‘cocktail parties of the geriatric set’ was after the death of President Reagan in 2004. In what the Thatcher Foundation calls ‘her last important public statement’,11 she delivered a eulogy at Reagan’s funeral, via pre-recorded video.12 She was the first non-American to do so at a President’s funeral. Lady Thatcher also attended Reagan’s burial and was photographed next to Arnold Schwarzenegger. ‘The Terminator meets The Iron Lady’, reported the Sunday Telegraph,13 while the Sunday Times went with the headline: ‘Shoulder to shoulder: The Terminator and Lady T’.14 There had been an earlier iconic image too. As Reagan lay in the Rotunda, Lady Thatcher placed her hand on his coffin. Having done so, she curtsied.15

Aspects of her life being brought to screen reinforced Lady Thatcher’s iconography. This included Margaret Thatcher: The Long Walk to Finchley in 2008, and Margaret in 2009. Reviewing the latter, Quentin Letts wrote of ‘the maddening, impossible, but ultimately great and dramatically irresistible figure of Margaret Hilda Thatcher, the Gloriana of the suburbs.’16

Then, in 2012, The Iron Lady was released. Although criticised because of its focus on Lady Thatcher’s illness, there was, however, 12praise for Meryl Streep’s performance. Matthew d’Ancona described the film as ‘a profoundly important revisionist tract’, noting: ‘It is curious to reflect that the main political event of the first week of 2012 is a film about a Prime Minister who left No. 10 more than 21 years ago.’17 Dominic Sandbrook wrote in similar terms, arguing that ‘Margaret Thatcher still dominates British politics’. He went on, ‘More than any of her rivals, she has become an icon, a cultural and political symbol.’18

After Lady Thatcher’s death, Michael Dobbs wrote, ‘Some 30 actresses have portrayed her on screen, few have come even close to getting her right.’19 Arguably, that is because the only actress capable of getting the character right was, in fact, Margaret Thatcher herself. ‘She used to say to me, “I’m not an actress”,’ remembered her speech writer, Ronald Millar, ‘but she certainly became one.’20 In 1992, the former Conservative Cabinet minister Lord Cockfield commented, ‘I have always said that Margaret envisages herself as Laurence Olivier playing the part of Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt.’21 Sir Gerald Kaufman, former Labour minister and one-time chair of the Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport, noted after Lady Thatcher’s death that ‘her international significance was emphasised … when, almost twenty-four years after she had stopped being Prime Minister, an actress in Hollywood could win the “best actress” Oscar for portraying her almost as well as she used to portray herself’.22

Lady Thatcher’s skill as an actress was seen throughout her premier emeritus years.23 Although a deeply serious person, not known for her sense of humour, when it came to timing, Lady Thatcher’s hardly ever failed her after 1990. Her ability at the great dramatic performance was to be seen in Thatcher: The Downing Street Years, the television series accompanying the first volume of her memoirs, 13while her skill at broad, almost end-of-pier performance was witnessed in the 1992, 1997, and 2001 general election campaigns.

As well as portrayals in film and television, photographs and paintings of Lady Thatcher after Downing Street also tended to emphasise the character that was Margaret Thatcher.

In 2008, for example, she was photographed by Mario Testino for a Vogue feature entitled ‘Tempered Steel’. When the Peruvian praised her for creating a Britain devoid of socialism, Lady Thatcher replied, ‘Yes, you’re right! People wouldn’t let you spend your own money. We chucked that all out!’24

The artist Richard Stone painted Lady Thatcher six times after Downing Street.25 One of those portraits was for her former study at No. 10, known as the Thatcher Room, and it was offered to Lady Thatcher by Gordon Brown when she visited him in 2007. Describing it as ‘a classic, historic portrait’, Stone reflected that it was ‘an extraordinary act of homage by the Prime Minister’26 and considered it the most important painting he had been asked to do.

‘Statesmen usually have to wait till they are dead before they are immortalised in bronze or marble,’ notes John Campbell.27 Lady Thatcher was an exception, seeing herself immortalised in both.

Sculptor Neil Simmons produced an eight-foot marble statue of the former Prime Minister, complete with handbag and weighing 1.8 tonnes.28 Unveiling it in May 2002, Lady Thatcher said, ‘I’m not bound to say anything but you can’t stop a woman, can you? I think it is marvellous.’ Setting the piece in its historic context, she noted: ‘It’s a little larger than I expected but that’s the way to portray an ex-Prime Minister who was the first woman Prime Minister.’ In character, Lady Thatcher noted that the statue had a ‘good, big handbag’.29 In July 2002, it was decapitated with a cricket bat and iron bar. The Times headlined the story, ‘The Iron Lady loses her 14marble head’ and reported that a man had been arrested for criminal damage.30

On 21 February 2007, a bronze statue of Lady Thatcher by Antony Dufort was unveiled at the House of Commons. Traditionally, the honour of a statue was bestowed posthumously, after ten years, though Speaker Michael Martin reflected, ‘It is right and fitting that Lady Thatcher’s period in office as the first woman Prime Minister should be celebrated while she was still alive’.31 ‘I might have preferred iron,’ she said at the unveiling ceremony, ‘But bronze will do. It won’t rust,’ adding: ‘This time, I hope, the head will stay on.’

Notes

1 Martin Amis, ‘The long kiss goodbye’, The Guardian, 2 June 2007.

2 Matthew Parris, Chance Witness (London: Penguin, 2002), p.212.261

3 Camilla Cavendish, ‘Thatcher’s spin control’, The Times, 26 March 2003.

4 Moore, ‘The mellowing of Margaret Thatcher’, op. cit.

5 Hilary Alexander, ‘The Iron Lady is back in style with fashion gurus’, Daily Telegraph, 27 January 2000.

6 Lisa Armstrong, ‘Style U-turn? Blame Mrs T’, The Times, 12 May 2004.

7 Julie Burchill, ‘Slimeballs always hate a strong woman’, The Times, 14 October 2004.

8 Vicki Woods, ‘Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady, used her wardrobe as a weapon’, Daily Telegraph, 12 April 2013.

9 Alistair Horne, Macmillan 1957–1986 (London: Macmillan, 1989), p.591.

10 Moore, op. cit., p.792.

11https://www.margaretthatcher.org/speeches

12 Thatcher MSS (digital collection), 110366. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110366

13 ‘The Terminator meets The Iron Lady’, Sunday Telegraph, 13 June 2004.

14 ‘Shoulder to shoulder: The Terminator and Lady T’, Sunday Times, 13 June 2004.

15https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ikIL_1zmNk

16 Quentin Letts, ‘Who’d have thought it? After decades of vitriol, the BBC’s making an honest woman of Mrs T’, Daily Mail, 18 February 2009.

17 Matthew d’Ancona, ‘Today’s contenders for power are all Thatcher’s children’, Evening Standard, 4 January 2012.

18 Dominic Sandbrook, ‘Blair, Brown, Major. In 100 years they will be long forgotten. But the world will still be in awe of the grocer’s daughter from Grantham’, Daily Mail, 7 January 2012.

19 Michael Dobbs, ‘It’s only now that I understand her’, Daily Telegraph, 13 April 2013.

20 Valerie Grove, ‘A playwright always needs a leading lady and for 16 soundbite-packed years it was Madam’, The Times, 7 May 1993.

21 Julia Langdon, ‘A treaty too farcical’, The Guardian, 12 November 1992.

22https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2013-04-10/debates/1304104000001/TributesToBaronessThatcher

23 Lady Thatcher’s skill as an actress had also been seen during her premiership. For more on this aspect of Lady Thatcher’s career, see Adrian Hilton, ‘The Art of Margaret Thatcher’, in Philip Norton and Matt Beech (eds), The Companion to Margaret Thatcher (London: Edward Elgar, forthcoming 2025).

24 Emily Sheffield, ‘Tempered Steel’, Vogue, July 2008.

25https://richardstoneuk.com/portfolio/leaders/baroness-thatcher

26 Simon Walters, ‘Thatcher finds a permanent home at No 10’, Mail on Sunday, 4 January 2009.

27 John Campbell, Margaret Thatcher, Volume Two: The Iron Lady (London: Jonathan Cape, 2003), p.798.

28 David Charter, ‘Iron Lady meets match in statue’s steely gaze’, The Times, 2 February 2002.

29 ‘Thatcher’s back, and larger than life’, The Times, 22 May 2002.

30 Tom Baldwin and David Charter, ‘The Iron Lady loses her marble head’, The Times, 4 July 2002.

31 Will Pavia, ‘Iron Lady returns, this time in bronze’, The Times, 22 February 2007. Accessible at Thatcher MSS (digital collection), 110913. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110913

Chapter Three

Political life

Private and public life aside, the focus of this study is Margaret Thatcher’s political life. As Jonathan Freedland said after her death, ‘Let’s talk politics: it’s what she’d have wanted.’1

Five themes

Lady Thatcher lived her political life largely within what we might call the infrastructure of the Office of Prime Minister Emeritus. In After Number 10: Former Prime Ministers in British Politics,2 Kevin Theakston highlighted five themes that are relevant to Lady Thatcher’s time as a premier emeritus: returning to office, health and age factors, honours, putting pen to paper, and money matters.

Returning to office

Some former prime ministers have returned to government after leaving Downing Street, most recently David Cameron when he was appointed Foreign Secretary in November 2023. This, however, was never a realistic possibility for Lady Thatcher. Nor was an official international role. Lady Thatcher recognised this. She received a private suggestion that she might become secretary-general of the United Nations,3 but ruled this out publicly, saying, ‘My views are far too strongly held for that.’4 In 1994, General Sir John Akehurst, former Deputy Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, reflected 16on a suggestion she might become NATO secretary-general: ‘She would get headlines,’ he judged, ‘but not consensus.’5

Health and age factors

Theakston noted that ‘longevity and good health are essential ingredients for a successful post-premiership’.6 Lady Thatcher certainly had the former, living over twenty-two years after leaving Downing Street. Her life up to 2002 was by any measure one of intense activity, and had illness not forced her effectively to retire from political life, it is likely this would have continued. It is also arguable, however, that in Lady Thatcher’s case, her ill-health helped to make her post-premiership even more successful than it would otherwise have been. Rather like when a relative dies, their family tend to remember only the good things about them, it was really in the years after she was silenced that Lady Thatcher’s mythological status reached its peak.

Honours

Lady Thatcher both proposed and received honours after ceasing to be Prime Minister. Her resignation Honours List was published in December 1990. She was awarded the Order of Merit the same month and the Garter in 1995.

Lady Thatcher was granted a peerage in 1992. She had decided to stand down as an MP in June 1991. This followed debate among her friends and supporters, some of which had been in the public arena. In March 1991, a Times leader, ‘Mother of the House’, argued that she belonged in the House of Commons. It described her as ‘the mother of the mother of parliaments.’7 In an ‘Open letter to an Iron Lady’ in The Spectator on 29 June 1991, Paul Johnson also urged Lady 17Thatcher to stay on as an MP.8 At the end of May, Cecil Parkinson9 and Sir Bernard Ingham10 had publicly advised her to stand down.

Lady Thatcher herself later wrote that she felt ‘ill at ease’ on the back benches. ‘The enjoyment of the back benches comes from being able to speak out freely,’ she said. ‘This, however, I knew would never again be possible. My every word would be judged in terms of support for or opposition to John Major. I would inhibit him just by my presence, and that in turn would inhibit me.’11 In his diary on 13 February 1991, Michael Spicer recorded, ‘We discuss Margaret Thatcher’s future as an MP. I say it’s selfish but we need her as a rallying point. She repeats “rallying point”! Then she says, “The only problem is I hate coming into this place now”, meaning the Commons.’12

That said, Lady Thatcher wished to retain her connection with Parliament. Speaking to Woodrow Wyatt in January 1991, she said, ‘I couldn’t not be connected with the Houses of Parliament.’13 In June that same year, she commented, ‘Whether from one house or another – I shall be there. I shall be there.’14

The day after the announcement that she was standing down, The Guardian published a leader, ‘And now we can all get on’. It opened with one word: ‘PHEW!’15 Ahead of an interview with Michael Brunson on 28 June, there was a photocall outside Lady Thatcher’s office. This provided a stage for her to play the character that was Margaret Thatcher. When asked about her energy, she responded that she had ‘tons of energy left’. Speaking to the journalists, she added, ‘I hope you have some’.16 Cabinet ministers were said to be ‘beaming with relief’ as they paid tribute to her.17

Until David Cameron’s elevation in 2023, Lady Thatcher was the last former Prime Minister to go the Lords. Once there, as in the 18Commons, she intervened rarely. In fact, she intervened in Parliament only fifteen times after Downing Street, making her one of the less parliamentary active ex-prime ministers. In comparison, her immediate predecessor as Prime Minister, James Callaghan, has to date been the most parliamentary active premier emeritus in British history, intervening almost 500 times.

As much of the commentary on Lady Thatcher’s speeches in the Lords makes clear, she was not temperamentally suited to the Upper House. One of her ministers observed to this author, ‘She needs the sort of clubbing to stir her up’, while a former member of her Cabinet reflected to us in 1999, ‘I suspect she didn’t really find the House of Lords very congenial, having a much more kind of seminar-like setting.’ Lady Thatcher herself alluded to this in a letter to John Major following her introduction to the Lords in June 1992, writing, ‘I only hope that proceedings in their Lordships House will sometimes be as exciting as question time in the Commons!’ Ever practical, she added, ‘scarlet and ermine is not the most appropriate clothing for a hot summer’s day’.18

Whether suited to the Upper House or not, Lady Thatcher was never not herself, both in the Chamber and in the Lords’ more informal spaces. Once, upon meeting Lord Richard, one-time Leader of the House of Lords and a former European commissioner, in the Lords’ bar, Lady Thatcher ‘complained loudly’ that there were ‘too many ex-commissioners in the Lords’. To which Lord Richard responded, ‘Some people might say there are too many ex-prime ministers.’19

As this anecdote demonstrates, Lady Thatcher was always able to generate a reaction in others. She had done this in the Commons, too. In her diaries, Edwina Currie recorded that in December 1991, Lady Thatcher had turned up in the Commons for the first day of a 19debate on Maastricht and there was ‘quite a kerfuffle over where she was to sit’. The next day, Peter Tapsell ‘made a point of coming into Prayers and took his seat’. On his Prayer card, he wrote, ‘Tapsell – in case M. Thatcher wants to sit here’. ‘Silly boys, all of them,’ Currie concluded.20

Lack of temperamental suitability was allied, and perhaps related, to a lack of understanding of the ways of their Lordships’ House. To this author, one of Lady Thatcher’s ministers observed, ‘The thing about Margaret Thatcher was she never understood the House of Lords all the time she was Prime Minister and still doesn’t.’ Lord Richard said the same thing, commenting to us, ‘She does not understand this House.’ He shared an anecdote too. ‘She turned up once to vote. She dashed into the Lobby which I was in, looked at me and said: “Oh, am I in the right Lobby?” So, I said: “Yes.” She said: “Now, as a man of honour, am I in the right Lobby?”’

Though speaking rarely, Lady Thatcher did attend the Lords for votes. In 1999, the former Leader of the House of Lords, Baroness Young, reflected on Lady Thatcher’s turning up for her amendments on the age of consent. Commenting to this author, Lady Young said, ‘I think people were pleased to see her. I was both pleased and to a certain extent surprised, because she hardly ever comes.’

When she did attend, her appearances generated a frisson. In June 1999, a former Labour Cabinet minister, Lord Merlyn-Rees, said to this author, ‘She’s in today. Everybody said: “What’s she doing here?” She never comes; she’s entitled not to come. I wonder why she’s here today. I’ve just no idea.’ What is fascinating is that a political opponent should be interested in, and seemingly care about, what Lady Thatcher was doing. In April 1999, a Labour frontbencher, Lord McIntosh of Haringey, commented to us, ‘Even when she comes in order to take part in an important vote … she doesn’t 20actually say anything. She just sits there and glares, the Gorgon, stone-faced.’ Lord McIntosh had earlier reflected, ‘She walks in, stony-faced, sits down, stony-faced, and leaves, stony-faced.’

Curiosity about motive was matched by awareness of Lady Thatcher being what Lord Norton of Louth has described to this author as ‘a presence’. This was something to which the shadow Leader of the House, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, referred in her tribute in April 2013: ‘As increasingly frail as she became, as a result of [her] enormous impact, her appearances in the House at key moments and on key Divisions were electrifying.’ Lady Royall spoke of being ‘mesmerised by this frail but still powerful woman’.21

Baroness Royall also noted another important aspect of Lady Thatcher’s later parliamentary career, namely the assistance she received from Michael Forsyth when she attended the Lords. Lady Royall spoke of ‘the real, caring support’ he gave her.22

Putting pen to paper

After resigning as Prime Minister, Lady Thatcher also put pen to paper, writing two volumes of memoirs: The Downing Street Years in 1993 and The Path to Power in 1995. Both generated considerable controversy, as did the supporting documentaries and interviews that were done in conjunction with their release. She also recorded audio versions of her books and undertook extensive promotional tours.

Not only did the content of The Downing Street Years generate coverage, but so did people’s reaction to the book around the world. The