22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

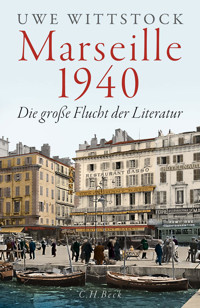

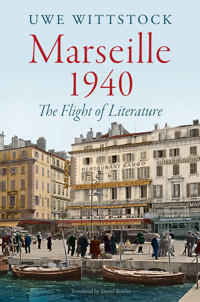

June 1940: France surrenders to Germany. The Gestapo is searching for Heinrich Mann and Franz Werfel, Hannah Arendt, Lion Feuchtwanger and many other writers and artists who had sought asylum in France since 1933. The young American journalist Varian Fry arrives in Marseille with the aim of rescuing as many as possible. This is the harrowing story of their flight from the Nazis under the most dangerous and threatening circumstances.

It is the most dramatic year in German literary history. In Nice, Heinrich Mann listens to the news on Radio London as air-raid sirens wail in the background. Anna Seghers flees Paris on foot with her children. Lion Feuchtwanger is trapped in a French internment camp as the SS units close in. They all end up in Marseille, which they see as a last gateway to freedom. This is where Walter Benjamin writes his final essay to Hannah Arendt before setting off to escape across the Pyrenees. This is where the paths of countless German and Austrian writers, intellectuals and artists cross. And this too is where Varian Fry and his comrades risk life and limb to smuggle those in danger out of the country. This intensely compelling book lays bare the unthinkable courage and utter despair, as well as the hope and human companionship, which surged in the liminal space of Marseille during the darkest days of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 623

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Prologue

Backstories

Two Days in July 1935

Berlin, July 15 and 16, 1935

Briançon, July 16, 1935

Sanary-sur-Mer, July 16, 1935

Vienna, July 16, 1935

Le Désastre

May 1940

Northern Eifel, May 10, 1940

Sanary-sur-Mer, May 14, 1940

London, May 15, 1940

Paris, May 15, 1940

New York, May 16, 1940

Abbéville, May 20, 1940

Les Milles, May 21, 1940

Gurs, late May 1940

Ljubljana – Paris, late May 1940

Dunkirk, May 26 to June 4, 1940

Paris – Sanary-sur-Mer, late May 1940

Loriol, late May 1940

June 1940

Paris – Toulouse, June 1, 1940

Paris, June 4, 1940

Dunkirk, June 5, 1940

Les Milles, early June 1940

Erquinvillers, June 9, 1940

Rome, June 10, 1940

Paris, June 11, 1940

Paris, June 11, 1940

New York, mid-June 1940

Toulouse, mid-June 1940

Tours, June 13, 1940

Paris, June 14, 1940

Meudon – Pithiviers-le-Vieil, mid-June 1940

Bordeaux, June 16, 1940

Les Milles, June 16, 1940

Orléans, June 16, 1940

Nice, mid-June 1940

Bordeaux, June 17, 1940

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1940

Marseille – Narbonne, June 18, 1940

Chasselay, June 20, 1940

Les Milles, June 21 and 22, 1940

Bordeaux, June 22, 1940

New York, June 22, 1940

Princeton, June 22, 1940

Bordeaux – Bayonne, late June 1940

Gurs, late June 1940

New York, June 24, 1940

New York, June 25, 1940

Bayonne – Nîmes, June 25 and 26, 1940

Narbonne – Bordeaux – Biarritz – Bayonne – Hendaye, late June 1940

Pontacq, late June 1940

Saint Nicolas, June 27, 1940

New York, June 27, 1940

Lourdes, late June 1940

Lourdes, late June 1940

Toulouse, late June 1940

Nîmes, late June to early July 1940

July 1940

Mers-el-Kébir, July 3, 1940

New York, early July 1940

Montauban, early July 1940

Paris, July 13, 1940

Toulouse – Marseille, mid-July 1940

Saint Nicolas – Marseille, late July 1940

Washington, D.C., July 26, 1940

Brentwood, July 28, 1940

Over the Mountains

August 1940

Lourdes – Marseille, August 4, 1940

New York, August 4, 1940

Paris, early August 1940

Marseille, early August 1940

Marseille, mid-August 1940

Marseille, mid-August 1940

Marseille, August 14, 1940

Marseille, mid-August 1940

Marseille, August 15, 1940

Provincetown, August 16, 1940

Marseille, mid-August 1940

Marseille, late August 1940

Marseille, late August 1940

Marseille, August 27, 1940

Marseille, late August 1940

Marseille, late August 1940

Marseille, August 29, 1940

Marseille, late August 1940

Marseille, August 31, 1940

September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, early September 1940

Marseille, mid-September 1940

Marseille, September 11, 1940

Marseille, September 11, 1940

Marseille – Portbou, September 12, 1940

Portbou – Barcelona – Madrid – Lisbon, September 14–19, 1940

Brentwood, September 20, 1940

Madrid, September 20, 1940

Marseille, September 20, 1940

Paris – Moulins, September 20, 1940

Cerbère – Portbou, September 21, 1940

Marseille, late September 1940

Marseille, September 23, 1940

Banyuls – Portbou, September 24–28, 1940

Paris, September 27, 1940

Pamiers, late September 1940

October 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Vichy, October 3, 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Marseille – Le Vernet, early October 1940

Marseille, October 7, 1940

Marseille, early October 1940

Banyuls-sur-Mer, October 13, 1940

Marseille, October 15, 1940

Saint-Gilles, October 19, 1940

Pamiers – Marseille, late October 1940

Hendaye, October 23, 1940

Montoire, October 24, 1940

Montauban, late October 1940

Vichy, October 27, 1940

Marseille, October 27, 1940

New York, October 30, 1940

The Villa, Waiting, and Death

November 1940 to February 1941

Marseille, late October to early November 1940

Marseille, early November 1940

Washington, D.C., November 5, 1940

Marseille, early November 1940

Marseille, early November 1940

Marseille, early November 1940

Vichy, mid-November 1940

Montauban – Marseille, mid-November 1940

Marseille, mid-November 1940

Marseille, mid-November 1940

Marseille, late November 1940

Marseille, late November 1940

Barcelona – Biarritz – Madrid, late November 1940

Marseille, December 2–5, 1940

Marseille, mid-December 1940

Marseille – Banyuls, December 13, 1940

Marseille, mid-December 1940

Marseille, mid-December 1940

Marseille, late December 1940

Marseille, late December 1940

Marseille, late December 1940

Provence, late December 1940

Sanary-sur-Mer, January 6, 1941

Banyuls, January 14, 1941

Marseille, mid-January 1941

Pamiers – Marseille, mid-January 1941

Arles, mid-January to early February 1941

Marseille, February 4, 1941

Paris, February 11, 1941

Marseille, February 14, 1941

Spring in France

February to June 1941

Marseille, mid-February 1941

Montauban, mid-February 1941

Marseille, February 1941

Marseille, late February 1941

Marseille, February and March 1941

Marseille, March 14, 1941

Marseille, March 1941

Marseille, mid-March 1941

Grenoble, mid-March 1941

Marseille, late March to early April 1941

Marseille, March 24, 1941

Vichy, March 29, 1941

Banyuls, April 1, 1941

Marseille, April 2, 1941

Marseille, April 9, 1941

Marseille, late April 1941

Marseille, May 1941

New York – Marseille, May and June 1941

Canfranc, June 1941

The Long Goodbye

June to November 1941

Vichy, June 2, 1941

Marseille, June to August 1941

Berlin, June 22, 1941

Washington, D.C., July 1, 1941

Vichy, July 22, 1941

Marseille, August 29 to September 7, 1941

Cassis, September and October 1941

Barcelona – Lisbon, September and October 1941

What Happened Afterward

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Varian Fry in Berlin, 1935

Alma Mahler-Werfel and Franz Werfel, 1935

Chapter 2

Hannah Arendt, around 1930

The Gurs internment camp in the Pyrenees, 1939

Miriam Davenport

Anna Seghers with her husband László Radványi and their chi...

Walter Mehring, 1929

Hertha Pauli

Lion Feuchtwanger in the internment camp Les Milles, 1939

Mary Jayne Gold

Chapter 3

A Clipper in flight

Château Pastré in Marseille

The transporter bridge in the Old Port of Marseille, with the Basilica Notre-Dam...

The Hôtel Splendide in Marseille

A Spanish soldier above the French border town of Cerbère, March 1939

Heinrich and Nelly Mann upon their arrival in the United States, 1940

The last known photograph of Walter Benjamin, from the official death registry o...

Justus “Gussie” Rosenberg above the Marseille harbor

Chapter 4

The Villa Air Bel in Marseille

André Breton in the library of the Villa Air Bel

Jacqueline Lamba, Jacques Lipchitz, André Breton, and Varian Fry

Hiram Bingham, American vice consul, on the transporter bridge above Marseille h...

Hans and Lisa Fittko in Marseille, 1941

Chapter 5

Jacques Hérold (standing), Max Ernst, and Daniel Bénédite h...

On the terrace of the Villa Air Bel, February 1941

Peggy Guggenheim in London, 1939 (In the background, the painting Le Soleil dans...

Refugees on the

Capitaine Paul Lemerle

, including Victor Serge (far left)...

Chapter 6

Varian Fry (right) with Daniel Bénédite at the office of the Centr...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

Marseille 1940

The Flight of Literature

Uwe Wittstock

Translated by Daniel Bowles

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in German as Marseille 1940. Die große Flucht der Literatur © Verlag C.H. Beck ohg, Munich, 2024

This English translation © Polity Press, 2025

The translation of this book was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge cb2 1ur, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, nj 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

isbn-13: 978-1-5095-6542-9 – hardback

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024946088

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk nr21 8nl

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Prologue

As a result of the German Wehrmacht’s campaign against France in May and June of 1940, eight to ten million people found themselves compelled to flee. It was a mass exodus of scarcely imaginable dimensions and perhaps the most enormous refugee movement Europe has ever witnessed in such a short span of time.

Among those refugees were hundreds of exiles from Germany and Austria who had fled from Hitler after 1933 and taken refuge in France. Now they had no choice but to leave everything behind a second time – their possessions, home, job, friends – and seek safety from the advancing Germans.

Marseille 1940 relates the drama of this second exodus. There is documentation for everything included here; nothing has been fabricated. The evidence stems from the written correspondence and journals, memoirs, autobiographies, and interviews of a number of great authors, theater folk, intellectuals, and artists. These people are the focus of this book. Along with them, countless unknown persons faced the same dangers, but the traces of their lives have been lost in the chaos of war and flight. The fates reported here shall thus stand in for all those we know too little about to be able to tell their stories. I would like to dedicate this book to the unknown refugees who fought for their survival in France in those days – far too many of them in vain.

At the same time, this is the story of a group of astonishing people who attempted, at considerable peril, to rescue as many exiles as possible from the deadly trap France had become for them. The tale of this group, centered around the American Varian Fry, traces back over a significant span of time and to several countries before these helpers ultimately converged on Marseille in 1940. They were to set an example of unflappable humanity in times of the greatest inhumanity imaginable.

BackstoriesTwo Days in July 1935

Berlin, July 15 and 16, 1935

Hessler, on Kantstrasse, is a somewhat old-fashioned restaurant decorated in dark wallpaper, chandeliers, and ponderous stucco work. The entire rear wall of its dining room is occupied by a massive, dark brown sideboard, the tables before it standing at attention as precisely as if a Prussian sergeant had mustered them for roll call. From Kantstrasse it is only a few steps to the famous Romanisches Café just behind the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche. But it is quieter at Hessler and not nearly as packed.

Sitting alone at one of the tables, Varian Fry eats his supper. He is from New York, twenty-seven years old, a journalist. If there is such a thing as the epitome of a classical East Coast intellectual, he comes fairly close to it: slender, of medium height, clean-shaven, with a serious, alert expression and rimless glasses. Fry takes his time with his meal; he has nothing further planned for the day.

The streets are more full of life than they have been in previous weeks. The Berliners are enjoying the pleasant metropolitan evening; up until now, the summer has far too frequently been gray and rainy. Fry came to Germany two months ago aboard the Bremen, one of the fastest transatlantic ocean liners. Since then, aside from a few side trips to other German cities, he has been staying at the Hotel-Pension Stern on the Kurfürstendamm, a respectable, bourgeois establishment with rooms at reasonable rates, fifteen marks a day.

Fry is here on a research trip. Some people in New York think very highly of him. He is regarded as one of the promising newcomers among the city’s journalists. When he returns to America at the end of the month, he will assume the role of editor-in-chief at The Living Age, a sophisticated, soon-to-be hundred-year-old monthly devoted primarily to foreign affairs – a tall order for a man as young as him – and he has clear ideas about the issues he wants to highlight for his readers in the future. By his estimation, the greatest threat in international politics is posed by the fascist regimes in Europe, by Italy, Austria, and, above all, Germany. And so he has arranged with the publisher of The Living Age to first spend a few weeks in Berlin to form his own opinion of Hitler’s new Germany before joining the editorial team.

Varian Fry in Berlin, 1935

You need not be a prophet, Fry believes, to realize that Hitler’s political strategy will ultimately result in a war. It is sufficient to take his appalling proclamations seriously, verbatim, and not turn a blind eye to what he is doing to the people in his own country. Not many Americans have the courage to do so, however. All the large newspapers between New York and Los Angeles are reporting on the Nazis’ martial demonstrations, the military’s buildup of arms, the waves of arrests, the concentration camps, but with these stories, they scarcely prompt more than a shrug among their readers. Europe is far away, while the misery of the Great Depression in their own country, by contrast, can be felt acutely. Every attempt to gain control of the tenacious economic crisis occupies the Americans ten times more than news about a far-off despot in a weird brown uniform.

Over previous weeks, Fry has traveled across Germany, conducting dozens of interviews with politicians, economic leaders, and academics, but also with shop owners, with waiters, churchgoers, and taxi-drivers, the so-called simple people off the street. He is also learning German to gain a more direct entrée to the country. His notebooks are full to bursting. Once he is back in New York, he will be able to provide information about Hitler’s state not only in abstract numbers and concepts, but also from personal experience, descriptively and concretely, as is proper for a reporter. He has a great deal planned: transforming The Living Age into an alarm bell that will ring in the ears of even the deafest and most complacent of Americans.

After eating, Fry settles up and calmly makes his way back to Hotel Stern, just a short evening’s stroll away. The boulevards in western Berlin are the city’s promenades, flanked by elegant shops, cafés, cinemas, theaters. This is where well-to-do citizens live who do not want to withdraw into the tranquil villa districts, but to know something of the pulse of the metropolis. If, despite the Nazis’ narrow-mindedness, Berlin still radiates something akin to international sparkle, then it is here.

Fry enjoys the warm evening, a relaxed summer atmosphere seemingly blanketing everything, until while turning from Kantstrasse toward the Kurfürstendamm he suddenly hears shouting, yelling, splintering glass, screeching brakes. It sounds like an accident.

Fry dashes off – and runs right into a street fight on the Kurfürstendamm. Young men in white shirts and heavy boots are surging into the road from the sidewalks on both sides of the street. They are stopping cars, tearing open doors, yanking the occupants from their vehicles, and pummeling them. A windshield shatters – shouting everywhere, tussling, men lying on the ground being kicked, women collapsing from the blows and crying for help. Fry witnesses uniformed SA men outside a café sweeping the dishes from a patio table with a swipe of the arm, hoisting it up, and throwing it through the shop window into the establishment. One of the double-decker busses is stopped, and several thugs shove their way inside, dragging passengers off and beating them. Again and again the shouts: “Jew! A Jew!” or “Death to Jews!” Intimidated passersby quickly wrest their papers from their wallets to prove they are not Jews. In a panic, a man wearing a dark suit sprints into a cross street as several pursuers chase after him.

Fry stands amid the tumult in disbelief; no one pays him any attention. He sees a white-haired man with a gaping, hemorrhaging wound on the back of his head. Bystanders spit on him. He sees women pushed around by caterwauling attackers until they stumble and fall. He sees trembling, distraught faces streaming with tears. He sees policemen, dozens of policemen, but they do not rush to the aid of those attacked. Men call them “Jew flunkies” or “traitor to the Volk.” The officers regulate traffic, clearing free passage for busses, but nothing more.

Then Fry becomes aware of the droning chant in the background. A voice grunts a few words, which Fry cannot make out. A second line follows, then a third, then a fourth. Finally, the voice begins from the top, and the hooligans within earshot, in white shirts or SA uniforms, take up the words recited and roar them back rhythmically. It is like the antiphony in a church between cantor and chorus. Fry still cannot understand what is being shouted. Later he will find someone to transcribe it for him: “When the trooper’s off to join the fight / oh, he’s in a happy mood, / and if Jewish blood sprays from his knife, / then he feels twice as good.”

Fry flees into one of the cafés whose windows have not been shattered. From there he observes the street – its entire width now under the control of those bands of thugs, not one pedestrian dares set foot on the sidewalk or the road. Two SA men enter the café and patrol along the tables. A solitary, potentially Jewish diner stiffens, turning his head away in an attempt to avoid being spotted by the uniformed men. The two men bear down on him; one of them reaches for the dagger of honor on his belt and raises his arm, plunging the blade down into the diner’s defenseless resting hand, nailing it to the tabletop. The victim screams, shrieks, stares horrified at his hand, while the men laugh, the one ripping the knife back out again. They leave the café smirking. No one stops them.

At this point, the ruffians now gather on the street. A tall young man gives a brief speech, little more than a concatenation of buzzwords and insults, and then a kind of protest procession forms. The men chant “Jews, out! Jews, out! Jews, out!”, raise their arms in the Hitler salute, and march up the Kurfürstendamm.

Fry leaves the café – the situation seems to have settled down – and walks the few paces to Hotel Stern. Back in his room, he tries to think straight. He moves to the window, looking down onto the street. After several minutes, the demonstration procession returns on the opposite side of the street, followed by a single, slowly idling police car. The men still shout slogans. Fry does not understand them.

When the protest march has finally disappeared, Fry takes a seat at the desk in his room, grabs his notebook, compels himself to be calm, and begins writing down what he saw.

At first glance, Varian Mackey Fry comes across as a young man spoiled by good fortune: the son of a stockbroker, talented, exquisitely educated, successful, worldly. But this first glance deceives. A crack runs across his seemingly so very affable existence. Since his birth in 1907, his mother has suffered from severe depression; she has spent a great deal of time in clinics and was, perforce, unable to care for her son as she would have wanted. Her illness has left its mark on Fry. In spite of his outstanding abilities, he leads a precarious life. The feeling of having been cheated out of something to which he was entitled has made him irritable.

Those who get to know him more intimately occasionally experience that dealing with him can be difficult. He has an unpredictable, rebellious side. Sometimes he behaves like a bulldog that latches on and cannot let go. In moments such as those, he shows no timidity about becoming unpleasant, polemical, or hurtful, although doing so does his intentions more harm than good.

Such outbursts have been part of him from an early age. Three times he was expelled from expensive boarding schools to which his father sent him. He numbered among the good students, in some subjects even among the superb ones. He loved the classical languages, Latin and Greek, most of all. Yet with some regularity he was overcome by the urge to rebel against the venerable, frequently somewhat ridiculous traditions of those fancy academies. And irrespective of which school he attended, he was always quickly viewed as a loner who set no store by endearing himself to others. On the contrary, he was often haughty and made others feel what little regard he had for people who swim with the tide.

With one exception: at Harvard University, he met Lincoln Kirstein, the son of wealthy Jewish parents from Boston. Like Fry, Kirstein was an enthusiastic proponent of avant-garde art, of new literature, music, and painting. While still in high school, Fry, upon learning that James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was on the index of banned books in the United States for pornography, had ordered a copy directly from the publisher in Paris. When he received it, his pride knew no bounds. He felt it was a badge of honor to possess it: a rebellious book for a rebellious young man. He could scarcely bring himself to put it down, reading from it to his fellow schoolboys, which swiftly prompted the next scandal, because the teachers did not think much of one of their pupils disseminating pornography in their boarding school.

Even then, Fry adored the provocative element of the avant-garde, its uncompromising nature, its willingness to break radically with conventions. When he found in Kirstein a like-minded soul, the pair founded a magazine, Hound & Horn, largely paid for with money from Kirstein’s father. They wanted to make their heroes of modernism popular at Harvard; they printed Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, or pictures by Picasso. Kirstein traveled to England with his parents, visited T. S. Eliot, and after his return attempted to persuade the university president to invite Eliot as a visiting professor. From its first issue, Hound & Horn made a tremendous impression – among the professors, too. In the blink of an eye, Fry and Kirstein were regarded as budding intellectuals, were praised, promoted, and passed around from party to party.

Much of the recognition Fry enjoys as a journalist still stems from this time. That magazine lent him the aura of a young man with a mind of his own and a keen eye for the issues of the future. He is considered a pugnacious man, but a certain intellectual rebelliousness is virtually to be expected of someone like him. Colleagues have dubbed him “Varian the Contrarian.”

Naturally, Fry at some point also clashed with Kirstein. Their magazine had an elitist reputation, and in order to appeal to a broader readership, Kirstein wanted to place more popular articles in the publication. Fry thought that lowbrow and staunchly defended its ambitions. In the end, an argument erupted, and Fry left the editorial team. He is not one for compromise.

In spite of his successes, he is eventually also in danger of being expelled from Harvard. He had stolen a “for sale” sign and erected it in front of the university president’s office because he considered him corrupt. This had been the last in a whole series of provocations with which he tried everyone’s patience. If the university nevertheless gave him one final chance, he owed it to the petition from an especially benevolent professor, and from an editor at Atlantic Monthly, Eileen Hughes. The letter from Hughes in particular made an impression; she mentioned his mother’s illness and insinuated that a bit more guidance from an “older and more sensible person” – she was six years Fry’s senior – could quickly set him back on a prudent path. What she left unmentioned was that the two were lovers, which had to remain secret until Fry sat for his exams. The week after, they got married.

That very night Fry sent his account of the street battle on Kurfürstendamm by cable to the New York Times. The editorial team is grateful to have found in him an independent witness to this largest antisemitic eruption of violence in years. To be sure, abuses against Jews have been taking place in Germany continually, but nothing of this magnitude. The newspaper prints the story about the bloody riot right on the front page; Fry’s description continues on page four.

The next morning, Fry telephones the Nazi Party’s informational Foreign Press Bureau to learn more about what prompted the disturbances. He harbors no great hope, expecting instead to be put off, but to his surprise, he receives an appointment for a conversation – he is to come right away. When he leaves the hotel and steps out onto the street, he sees that the building façades along Kurfürstendamm are practically plastered with anti-Jewish posters. He scrutinizes them: the distorted faces with their hook noses, wanton mouths, and bug eyes. When he tears down two posters, policemen walk up to him with the intent of arresting him. They shove him into the foyer of a cinema and ask for his identification papers. He has no time to lose – he has an appointment at the Nazi party office – so he pretends to be the clueless tourist claiming he took the drawings for newspaper advertisements. Could he keep the posters? He would like to take them back with him to America as souvenirs. As soon as the officers hear his accent, they become more agreeable and issue only a warning; it was party propaganda that must not be removed. To his question about whether the commotion from yesterday was also party propaganda, he receives only a vague nod.

The office of the Foreign Press Bureau is located just behind the Brandenburg Gate on Wilhelmstrasse. There, a different mood prevails than in the German administrative offices Fry has so far visited. No one barks “Heil Hitler” or thrusts out their right arm; the atmosphere is more civilian. The press chief himself, Ernst Hanfstaengl, approaches Fry. He is a hulking man nearly two meters tall, his hair slicked back and parted severely down the middle. He comes across as a circus director about to brandish his top hat to announce the big animal act.

Hanfstaengl speaks English beautifully, so well that Fry can make out the cadence of the typical Harvard graduate. He comes from a rich Munich publishing family and worked for a while as an art dealer in New York after his university studies, before becoming Hitler’s henchman back in Germany. But he does not fit in with the other party vassals. He has nothing of their brutality and their consciousness of power. His office, half scholar’s cloister, half chaotic editorial parlor, is stuffed full of file folders, books, and stacks of old newspapers, and has a piano in the corner.

The conversation takes a different course than Fry expected. Hanfstaengl is no diplomat, no man of subtle undertones. Apparently, he wants to impress his guest – who comes from the same university as he – with the autonomy with which he brushes aside all conventions of political speech. The claim on the part of German newspapers that the riots were a spontaneous outburst of popular anger he dismisses out of hand. Everything, he says, has of course been organized by the folks in the party. The Gloria-Palast on Kurfürstendamm is currently screening a Swedish film, Pettersson & Bendel, a cheap whodunnit, in which a smarmy Jewish baddie tries to get the better of a radiantly blond Aryan businessman – and fails, naturally. On the previous Friday, three days before the riot, there were attendees in the theater who pretended to be scandalized by the film’s antisemitic bias and disrupted the show with heckling and loud hissing.

The hecklers were of course not Jews, but provocateurs, Hanfstaengl says, SA men in civilian clothes under orders to act like Jewish troublemakers to provide a paltry pretense for the long-planned pogrom. Der Angriff, far and away the favorite paper of Joseph Goebbels, then went to print on Monday afternoon with a fiery lead article warning the Germans about the allegedly brazen behavior of Jews and calling on them, finally, to fight back. After that, Goebbels only had to send his people outside the Gloria-Palast and let them start swinging fists as the whim took them. Most had worn white shirts, likely as a disguise, and not their SA uniforms.

Fry listens to Hanfstaengl, amazed. It is not the SA’s duplicity that surprises him – on the contrary, there were many indications that the riot was staged – but the fact that a press officer would so unguardedly spread his party’s secrets, and in front of a foreign journalist, to boot, who might easily escape censorship? Fry did not expect that. Naturally, Hanfstaengl every so often drops hints that some of his comments are confidential and may not be quoted by Fry publicly. But he clearly has no desire to phrase the key points with circumspection. He lunches regularly with Hitler! They have been friends since the early years of the movement! He was even there for the march on the Feldherrnhalle in 1923, Hitler’s attempted putsch. Why shouldn’t he say bluntly what he thinks?

Hitler, Hanfstaengl is convinced, puts up with the wrong men in his ambit. Göring and Goebbels? Both fanatics pushing him in a sinister direction. It hardly goes unnoticed that Hanfstaengl considers only one man capable of advising Hitler competently: namely, Hanfstaengl himself. And it is of the very greatest importance, he insinuates, that he in fact get through to the Führer. There are, he explains to Fry, two contentious camps among Hitler’s paladins. A moderate group would like to house the Jews in specially designated reservations in order to segregate them systematically from the Aryan population. The radical group, on the other hand, wants to solve the Jewish question with a bloodbath. Fry hears Hanfstaengl’s words echo in his mind as the two men shake hands goodbye. He said bloodbath.

On the way back to Hotel Stern, Fry realizes that he has heard something seldom uttered so explicitly and of which almost no one in America is aware. If Hanfstaengl speaks of a bloodbath, then what is meant is murder – mass murder of the Jews. How many hundreds of thousands of Jews are there in Germany? Does the radical faction of the Nazis actually want to kill them? Can a bloodbath of such magnitude even technically be carried out? Hard to imagine. Hanfstaengl, however, moves within Hitler’s innermost circle. What a man like that says, Fry cannot discount as nonsense.

He does not know what he is to make of this conversation, but two things are clear. First, it would be better for his health were he not to speak of Hanfstaengl’s remark while still on German soil. And second, he must not withhold it from American newspaper readers. In his next article for the New York Times, he has to mention what Hanfstaengl divulged. Perhaps that will finally open Americans’ eyes to the sort of people currently holding power in the middle of Europe.

Briançon, July 16, 1935

Heinrich Mann no longer sports a goatee. He shaved the narrow band of hair between lower lip and the tip of his chin that gave him a mildly rakish aspect; his mustache, which has since gone gray, was all he kept. This makes him appear more courtly, perhaps even younger, but also a bit prudish.

On the same day Varian Fry learns of unfathomable plans in Berlin, Heinrich Mann takes the time in the French Alpine town Briançon to draft a long letter to his brother Thomas in Switzerland. Heinrich is staying in the venerable Hôtel du Courts with his companion Nelly. They are here for a respite; in midsummer, Briançon is refreshingly cool, the mountains offer wonderful vistas, and in the Old Town the little houses huddle against the mighty collegiate church like chicks beneath the wings of their mother hen. Nelly, nearly thirty years younger than he, is not especially bothered by the summer heat of Nice, where they have been living since their escape from Germany, but he, now sixty-four, needs a break. The past two years in exile were trying for him.

He has long put off writing this letter to Thomas. There are all sorts of things worth relating, but Heinrich wants to dress up the news with a diplomatic tone so as not to imperil in any way the reconciliation between them – a reconciliation that too often seems as though it were nothing but a non-aggression pact.

During the First World War, they had burned all the bridges between one another. At the time, Thomas was trumpeting his enthusiasm for war throughout the country, indulging in ethnic-psychological clichés about the soulfulness of the Germans, the mercantilism of the English, and the merely expedient, pseudo-civilized nature of the French. A pacifist and admirer of French literature, Heinrich could not stomach that much nationalistic bigotry. In public, both exercised restraint; for the uninitiated, the few printed allusions to their rift were nearly impossible to decipher. In private, however, they exchanged contemptuous letters that left deep wounds. Not until four years after the war, in 1922, did the pair call a party truce within the family – which proved sustainable also because Thomas had done a radical about-face in matters of politics, having finally committed himself to the republic and democracy. But very warm their relationship is not. Their dealings with one another are cautious, almost a bit ceremonial, and they endeavor not to provoke their old divisions.

After more than two years of hard and concentrated labor, Heinrich has just finished Young Henry of Navarre, the first of two novels about the man who rose to become king of France in the sixteenth century. It is his most important and best book in years, confirmed for him by everyone permitted to read the manuscript in advance: a diligently researched, grand historical apologue, dedicated to a ruler who not only led his country to newfound strength, but who also cultivated within it unprecedented tolerance and liberality in matters of religion. At first it sounds as if Mann had dreamed his way back from the politically dark present into an inviolate, humane past, but in the novel, he lends the antagonists of his wise King Henri IV some easily identifiable features of Hitler and Goebbels, making the book a reckoning with the Nazis as well.

In his letter to Thomas, though, he makes no mention of any of this. It would not interest his brother or, worse, might reinflame the literary rivalry between them. He would much rather give an account – in the most innocuous way possible – of the spectacular Writers Congress that he, but not Thomas, attended three weeks earlier. More than two hundred fifty authors from all over the world had traveled to Paris, among them such illustrious colleagues as Bertolt Brecht, André Gide, Lion Feuchtwanger, Anna Seghers, Aldous Huxley, André Breton, and Boris Pasternak. Despite the scorching heat blanketing the city, more than three thousand auditors packed into the large hall of the Maison de la Mutualité. The goal was to establish a united front of protest against the Nazis within the cultural milieu. The many quarreling mini-factions of communist, socialist, Social Democrat, emphatically Christian, or bourgeois-liberal authors were finally to be committed to a strong alliance of resistance against Hitler and Mussolini.

The congress had been the idea of communist authors, or more specifically: those loyal to Moscow. Suspicion quickly spread that it was secretly tasked with securing a better reputation and more influence among intellectuals for Stalin’s regime; the Soviet Union wanted to be regarded as the only morally acceptable alternative to the fascists’ terror and the capitalists’ exploitation. Heinrich Mann was aware of the organizers’ poorly concealed intentions, but he put up with such propagandistic ulterior motives. In his eyes, without the backing of the emergent Soviet Union, bourgeois Europe is a lost cause as it is.

Of course, not every one of the two hundred fifty authors attending was able to say his piece at the congress. But the organizational committee had expressly requested that he, Heinrich Mann, speak. When he approached the podium, the entire hall rose to its feet, among them Europe’s most important writers, honoring him with sustained applause. In the galleries, where the communists had placed their rank and file, some began singing the “Internationale” but were silenced immediately by the shouts of others. The swelling song would otherwise have made all too clear the extent to which the convention was dominated by Stalin’s people. Even so, the imperative tone that stifled that spontaneous gesture like a shot was essentially just as telling.

After Heinrich’s appearance, he was joined on stage by Thea Sternheim, the ex-wife of Carl Sternheim, whose satiric dramas had impressed him again and again. They knew each other well but had lost contact with one another for several years. Thea Sternheim had possessed sufficient foresight to leave Germany months before Hitler’s assumption of power; now she was living in Paris. In contrast, Heinrich Mann had realized only at the last minute that his renown was unable to protect him from the Nazis. From Berlin he had traveled as inconspicuously as possible by train to the Rhine, disembarked in the tiny border hamlet of Kehl, and walked across a bridge to France, a valise in one hand, an umbrella in the other – he could not manage to salvage more for his exile. It had almost been too late. One day after his escape, SA men stormed his Berlin apartment to take him into custody.

Thea Sternheim and he soon found their way into familiar conversation, exchanging recollections of their Berlin years. Then, however, André Gide approached them, and thus began a peculiar game. Gide had also known Thea Sternheim and Heinrich Mann for quite a number of years, and he requested they leave the overheated auditorium for a quick half hour at the café Les Deux Magots on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. They went with him, but Gide was continually distracted, compelled to greet acquaintances here and there and yonder while exiting the building, and he kept the two waiting. Even when they arrived at the café, he invited a married couple with whom he was on friendly terms to join them at their table, conversed only with them, and spared hardly a word for Heinrich Mann. Heinrich quickly realized what he was to make of this. Gide was regarded as France’s most important writer and thus also viewed himself as the star of the congress. As a result, the audience’s salutes to Mann had offended him in his sense of rank, and now he intended to make him feel who in fact was the most celebrated author here in Paris.

There is no way Heinrich can write his brother about all of this. Needless to say, Thomas Mann considers himself the literary sovereign among German expatriates – even if he has been keeping a low political profile and still has not yet publicly broken with the Nazis. If Heinrich were to mention in his letter the enormous show of respect bestowed upon him at the congress, Thomas might react as jealously as André Gide.

The newspapers, however, have reported on Heinrich’s triumph, so he cannot completely hide this fact from Thomas, just try to mitigate it. And so he mentions how spectacularly the congress went. The uniting of all non-fascists, by no means only the communists in thrall to Stalin, proved a success. “Whenever a German appeared on stage,” he continues, “the whole house rose to its feet, and from above they began singing the Internationale. But the singers were met with shouts of Discipline, camarades! – and then they stopped.” It is admittedly a rather unlikely scene for every German speaker to have been given an ovation, for the “Internationale” to have been struck up each time, and each time for it to be cut short. All the same, however, it disguises Heinrich’s success without completely concealing it.

At the conclusion of his letter, Heinrich offers one last admission to his brother. In May, Thomas and his wife Katia, a couple as urbane as they are implacable, visited him and Nelly in Nice. At the time, Heinrich was writing the final pages of Young Henry of Navarre but dropped everything to fetch the two from the train station and drop them at their hotel. It was simply impossible, however, to hide that Nelly came from a very different social stratum than their guests.

Heinrich had met Nelly six years earlier in Berlin, at the Bajadere, a nightclub near the Kurfürstendamm where she worked as a bar girl. Her real name is Emmy Westphal, but she goes by Nelly Kröger. She is a strawberry-blond, voluptuous beauty, fun-loving, often quite loud, and a touch forthright. She knows nothing of literature or art, she is the daughter of a maidservant, she was born out of wedlock, and her stepfather is a simple fisherman. Never did she have opportunities for a solid school education. In other words, the conventions of intellectual conversation are alien to her. On top of this, she drinks more than is good for her.

This does not bother Heinrich. He has never cared a whit about the rules of bourgeois respectability. He loves Nelly for her youth, for her candor, and not least for her courage in sharing his emigration with him. She only landed on the Nazis’ radar because she had been living with him in Berlin and had helped him escape. That would probably not have been an insoluble problem; one of her stepbrothers is a squad leader with the SS. With his connections, she would surely have been able to find a way, in spite of it all, to remain in Germany. Instead, however, she opted for Heinrich, for life at the side of a much older writer whose future prospects in exile are now very uncertain.

Thomas and Katia brought a bouquet of roses to Nelly for their first meeting with her in Nice. They were intent on establishing friendly relations with her, but once the four of them were sitting at dinner at Régence, one of the city’s finest restaurants, and Nelly drank uninhibitedly and prattled on, she got on Thomas’s nerves. In his eyes, she is nothing but a silly, terribly vulgar person.

The following evening did go better. Heinrich had invited his brother and sister-in-law to the new flat on the Rue du Congrès. Nelly prepared a first-rate dinner, they conversed with one another in the drawing room late into the night over red wine and coffee, and the mood was fantastic. Nelly, however, spent the majority of the evening in the kitchen tending to the pots such that she was hardly able to participate in the conversations, which was a huge relief to Thomas.

Heinrich noticed that. These days he is especially gentle, almost humble when engaging with his brother. He does not want any tensions at all to arise, and so he ends the letter he is now writing him in Briançon with an emphatically formal final line: “Frau Kröger sends thanks for your greeting and reciprocates it.” This sounds as if Nelly were his housekeeper, not his companion. But Heinrich is aware that his class-conscious brother, the Nobel Prize winner, would rather abstain from informal familiarities with Nelly.

Sanary-sur-Mer, July 16, 1935

Marta is merciless when it comes to his work. She would never tell him what he wants to hear. For Feuchtwanger, that is important; he knows he can rely on her judgment. For much too long now, he has been torturing himself with the final chapter of his new novel, The Sons. A week earlier, on his fifty-first birthday, Marta was especially lovely and loving throughout the day, but when he read to her from his manuscript that evening, she rejected it stridently. Not even a birthday can put her in an indulgent mood, not in matters of literature. Afterward, he slept poorly and spent the next few days making endless changes and emendations.

Today the newspapers contain awful reports out of Germany. Evidently, the SA in Berlin organized a veritable witch hunt for Jews, not secretly in some remote district, but right in the middle of the Kurfürstendamm, in front of the world. Here at their home in radiant Sanary-sur-Mer, beneath the skies of southern France, such accounts take on an unreal aspect. It is difficult to believe them possible. All day long, Feuchtwanger has continued working on the manuscript with Lola, persistently and plagued by doubts, until finally everything seemed to cohere. Then, in the evening, he reads the new ending aloud to Marta, but this one, too, she dislikes. She is still not satisfied.

Lion Feuchtwanger long ago stopped drafting his novels himself; he dictates them, which goes faster. Together with Lola Sernau – she will soon have been his secretary for ten years – he has developed a method of advancing the manuscripts in several steps and readying them for print. This is the easiest way for him to proceed with work. So as not to mix up the various versions, they use colored paper. He dictates the first version to her on blue paper, then the second on red, the third on orange, the fourth on yellow, and then finally the fair copy on the usual white. In this manner he can expeditiously expand, rework, and tweak his text, from one step to the next, until it is right.

Fortunately, the relationship between Lola and Marta has recently improved somewhat. Marta is usually pleasant to the women with whom Feuchtwanger sleeps, but as soon as they attempt to contest her, his wife’s, place in his life, she mans the barricades. Then she strindbergles, as Feuchtwanger calls it (thus likely comparing her to Swedish playwright August Strindberg’s volatile character Miss Julie). It sounds ironic, but when Marta’s wrath is unleashed, it gets uncomfortable for him, too.

For around two years now, Lola has been one of the women on the side with whom Marta has to come to terms. Once she caught Lion and Lola in the act, which was awkward for everyone, but for Marta was not actually a surprise. There was never any talk of sexual fidelity between herself and Feuchtwanger, and he makes no secret of his incessant erotic appetite. The usual secrecy and uptightness associated with screwing around are not to his taste. She, too, occasionally has affairs, yet is much more discreet than he and not as indiscriminate.

When Feuchtwanger was still slogging along as a critic toward the beginning of his career, he limited himself to brief flings or prostitutes. Then came his first successes as a writer with his theatrical works, and he met Eva Boy, an expressionist dancer, very boyish, very athletic, and only just turned nineteen, not even half as old as he. Eva was a complicated woman who skidded from one crisis to the next. Once she attempted to kill herself with sleeping pills, but Marta noticed in time and was able to save her.

When Marta and Lion moved to Berlin from Munich, Eva went along; her relationship with Feuchtwanger went on for years. In Berlin, he rose to the rank of a bestselling author, and while his novels made him not only world-famous but also filthy rich, he became almost sexually insatiable. Sometimes he had five or more paramours at the same time, without forgoing prostitutes. He is a short, wiry man and certainly not handsome. But his intelligence and his uninhibitedness in getting right to the point when flirting have an animating effect on many women. For the villa he and Marta had built for themselves back then in Grunewald, they planned separate bedrooms, which accommodated Lion’s escapades.

Fleeing from Germany has changed their lives astonishingly little. Of course it was a tough loss when the Nazis confiscated their home in Grunewald, but the Villa Valmer, which they rented here in Sanary, is ultimately even more beautiful. Brilliant white, it is situated on a hill in the town amid a large, lavishly burgeoning garden with a clear view of the sea. The curving coastline, with several ornamental islets as well as Sanary’s tiny fishing harbor, comes across as the setting in a dream. Rambling up the slope to the right and left of the house are olive trees, fig trees, and stone pines. The house has generous high-ceilinged rooms, a wonderful terrace, a bright, airy office for Lion – you cannot live much better than this. While moving in, Feuchtwanger was initially skeptical, but now he has practically fallen in love with the house.

Naturally, there are other women besides Marta and Lola here, too. Since Hitler’s assumption of power, Sanary has transformed into a refuge for many German emigrants, men and women alike. In addition, the town has for decades been the chosen home of a considerable gaggle of artists and bon vivants such as the gorgeous American illustrator Eva Herrmann or the opera singer Annemarie Schön, who sleeps with Feuchtwanger now and again, but expects a monetary gift in exchange each time.

The Côte d’Azur has a further allure, moreover, that he finds hard to resist. There are a number of casinos here. Feuchtwanger loves to gamble, which has been his second vice since his youth. Most of the time he loses. In the past, his gambling debts occasionally reached worrisome levels, and Marta had to learn to shepherd him through nasty financial straits. The days are over, however, when publishing houses throughout the world would wire him truly princely fees for his books.

Like Heinrich Mann, Feuchtwanger also visited the Writers Congress in Paris. For weeks beforehand, author friends of his had importuned him to attend – most of all authors who maintain stellar connections with the Soviet Union. At first he hesitated, because a sordid incident that grew into a real tragedy had taken place during the preparations for the meeting.

The quarreling all began with one of the slanders common to the literature business. Ilya Ehrenburg, a Russian writer who lives primarily in Paris and who was among the organizers of the congress, badmouthed the French surrealists in a newspaper article using the typical tone of Stalinist functionaries. He labeled them mentally ill and indolent, called them “young lads who make a business out of insanity,” waste their time with “pederasty and dreams,” and shamelessly fritter away their parents’ or wives’ money.

A cheap, parochial polemic, but within the Parisian literary world, it caused a considerable scandal and provided plenty of fodder for conversation. It was mostly André Breton, who sees himself as the inventor and pioneer of surrealism, who felt defamed by the attack. He is a proud, power-conscious man who unfortunately lacks any sense of humor and – perhaps also for this reason – reacts with particular irascibility to criticism.

Although Breton, like Ehrenburg, lives in Paris, the two have never met. Yet they happen to cross paths on the Boulevard du Montparnasse just a few days before the congress is set to begin. Both of them are pugnacious men with sweeping black manes they comb back severely. Ehrenburg had just left a café and was about to cross the street when Breton walked up to him and addressed him:

“I have come to settle an affair with you, monsieur.”

“And who are you, monsieur?” Ehrenburg asked.

“I am André Breton.”

“Who?”

At which point Breton repeated his name several times in a row, always together with a slap in the face and one of the insulting appellations Ehrenburg had given to the surrealists. He was the mentally ill Breton. Slap. The indolent Breton. Slap. The insane Breton. Slap. The pederast Breton …

Ehrenburg mounted no defense against the blows, only protecting his face with his hands and threatening: “You’re going to be sorry for this.”

Indeed, Ehrenburg subsequently managed to force through the organizational committee of the Writers Congress that neither Breton nor any other surrealist would be permitted to give a speech or even set foot on stage during the meeting. He wanted to banish Breton’s people from public life, literally to revoke surrealism’s literary right to existence. Vehement disputes broke out on the committee over this. The young poet René Crevel in particular, who, like Ehrenburg, was a member of the Communist Party but at the same who worshipped André Breton as his literary “god,” attempted to prevent Breton’s exclusion by all available means. When Crevel was forced to realize after hours of exhausting debates that he could not reverse the decision, a tragedy occurred. He left the committee’s office, went to his apartment, wrote on a slip of paper “burn me,” opened the gas valve, and killed himself.

It quickly became apparent that Crevel had probably not been driven to suicide by the conflict between Breton and Ehrenburg. Rather, he had been suffering from tuberculosis for years and had learned from a doctor shortly before the deed that the disease was now destroying his kidneys and he did not have much time left. Nevertheless, wild rumors about Ehrenburg’s campaign of retaliation against Breton circulated immediately. To take the wind out of their sails, the organizational committee had no other choice but to find a compromise. In Paul Éluard, they put on the speakers list a well-known lyric poet and close friend of Breton’s who was now officially permitted to speak on behalf of the surrealists.

Feuchtwanger does not care for such quixotic feuds. He is not as involved in political matters as Heinrich Mann; in the end, he did not find the congress very enticing. But when word got out that Lilo Dammert would be there, he decided to travel to Paris for a week after all. Lilo is a scriptwriter; he has known and admired her since they met in Berlin. Nevertheless, he has still not yet been able to get her to sleep with him.

The weather is radiantly beautiful when he arrives in Paris. The city presents itself in its full glamour. He has hardly arrived at the hotel when calls from the organizational committee reach him. A few days earlier he was told he could of course give his speech in German. Now, suddenly, it turns out that he is to speak French. Right away he hires a secretary and a translator and begins to rework his text in a frantic hurry; his appearance is scheduled for the very next day. Even so, he keeps the evening free for Lilo Dammert. They go out, and of course he flirts with her. She has a grand time but resists his attempts at seduction.

Back at the hotel, Feuchtwanger cannot sleep. The translation of his speech preys on his mind. In the morning, Bertolt Brecht stops by briefly. They have known one another from their years in Munich and Berlin, and he, too, will speak at the congress. Then Feuchtwanger continues working on his text. That afternoon he brings in a second translator. By evening, the speech is finally ready. He has stage fright, walks into the boiling hot convention hall, but is made to wait. When he finally gets to speak at around midnight, his talk falls flat. No one takes up his ideas. No standing cheers like for Heinrich Mann, just minor obligatory applause.