Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

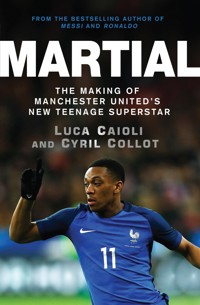

On 1 September 2015, Anthony Martial completed his transfer from Monaco to Manchester United. At just 19 years of age, the fee of £36m (potentially rising to £58m) made the France international the most expensive teenager of all time. Eyebrows were raised at the landmark fee but a goal against Liverpool in his first game helped get the supporters onside, while a number of key strikes in his debut season soon won over the critics as he became integral to Manchester United's attack. Renowned sports biographers Luca Caioli and Cyril Collot talk to coaches, teammates and even Martial himself, to provide an unrivalled behind-the-scenes look at the life of the teenage superstar.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 271

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MARTIAL

MARTIAL

THE MAKING OF MANCHESTER UNITED’S NEW TEENAGE SUPERSTAR

LUCA CAIOLI and CYRIL COLLOT

Translated from the Italian and the French by Laura Bennett

Published in the UK and USA in 2016

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services,

Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada

by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300, Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed in the USA

by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

ISBN: 978-178578-097-4

Text copyright © 2016 Luca Caioli and Cyril Collot

English language translation copyright © 2016 Laura Bennett

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

About the authors

Luca Caioli is the bestselling author of Messi, Ronaldo, Neymar, Suárez and Balotelli. A renowned Italian sports journalist, he lives in Spain.

Cyril Collot is a French journalist. He is the author of several books about the French national football team and Olympique Lyonnais. Nowadays he works for the OLTV channel, where he has directed several documentaries about football.

Contents

1 Soaring towers

2 In the footsteps of Henry and Evra

3 The meeting

4 Between Manchester and Lyon

5 Discovering a new world

6 Already at national level

7 The new baby gone

8 Welcome to the pros

9 5 million euros

10 Regrets

11 Toto and the tsars

12 Cloudy skies over Monaco

13 Punishment

14 The click

15 A busy summer

16 The longest day

17 Anthony who?

18 A fairy-tale start

19 Wembley, 17 November 2015

20 A Christmas present

21 Goals, gossip and love stories

22 Anthony Le Magnifique!

23 Back home

24 Missed

A career in figures

Color Plates

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Soaring towers

‘Why are the people who live in Les Ulis so surprised by the Bergères Towers? Why do they always ask why sixteen-storey buildings have been placed so close together when there is so much space around them?’ The answer offered by a welcome pamphlet distributed to new arrivals is simple: ‘The architects had no choice. They had to fit 10,000 homes on 200 hectares, not a handful of detached houses scattered across a park.’

Anthony Martial grew up in one of the soaring Bergères Towers, white, grey and pale coffee-coloured high-rise blocks that sprout up side by side in the centre of Les Ulis. We are twenty kilometres south east of Paris, in the département of Essonne, Île-de-France. On 17 February 2017, Les Ulis, caught between the A10 motorway and the 118 trunk road, will celebrate the first 40 years of its existence.

The story of Les Ulis began in 1960, when a ministerial decree authorised the urbanisation of an area between the towns of Bures-sur-Yvette and Orsay. It was intended to house employees, managers and researchers working for the Atomic Energy Commission, the large companies at the Courtabœuf business park, and the Université Paris Sud. In 1965, work started on the grassy fields used at that time for cultivating wheat, beetroot, strawberries and vegetables. France was experiencing a time of pronounced economic growth and improved living conditions during the period that would come to be known as the Trente Glorieuses. Robert Camelot, François Prieur and Georges-Henri Pingusson, the urban planners who designed Les Ulis, were inspired by the ideas of Le Corbusier: housing complexes, squares designed as terraces, internal streets for shops, and the separation of traffic flow, with walkways for pedestrians and streets for cars. It was a raised or elevated form of urban planning, an architecture of growth found in suburbs all over France. In 1968, the new development’s first inhabitants moved into the Bathes and Courdimanche districts, although some buildings were yet to have running water. Eight years later, on 14 March 1976, the citizens of Bures-sur-Yvette, Orsay and the new town were called upon to choose between three proposals in a referendum: maintaining the status quo, the current administrative situation at that time; opting for Bures-sur-Yvette and Orsay to be merged to encompass Les Ulis; or creating a new, third commune called Les Ulis. The winner, by a very slim margin, was the third option, and, on 17 February 1977, the 196th commune of Essonne, Les Ulis, officially came into existence. Once again, the welcome pamphlet explains that its name ‘comes from the Latin verb “uller”, which means “to burn”. The name of the town is derived from the ground on which stubble was burned to make fertiliser.’

In March 1977, Paul Loridant, a 28-year-old socialist, was elected mayor. His mandate would be renewed six times: he spent 31 years governing the town. The former Banque de France employee and one time senator for the Mouvement républicain et citoyen is now 68 and currently the deputy mayor in charge of finance and social affairs.

He remembers: ‘When I arrived, the town was a huge open-air construction site. There was still plenty of building to be done: the market, post office, town hall, the Boris Vian cultural centre, but there were already 20,000 inhabitants, people from all over France who came to work elsewhere in the region, or in Paris.’ Eighteen per cent of the inhabitants were back then, and still are, of foreign origin.

Portuguese, Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians, immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa (Mauritania and Mali), Réunion and the Antilles (Guadeloupe and Martinique in particular). The population grew rapidly until 1982, when the inhabitants of Les Ulis reached almost 29,000, but this was followed by a slow demographic decline and consequent decay. Today, the municipality is home to barely 25,000. The percentage of young people living in the town has also fallen significantly. Why? According to Paul Loridant, the unresolved problem with Les Ulis is the integration and social evolution of a population of humble origins: ‘We have not been able to stop people leaving when their standard of living improves and they start climbing the social ladder. They prefer to move to neighbouring towns, such as Orsay or Limours, or closer to Paris, where they think they will have a better life, where society is more mixed. In Les Ulis, where we have more than 50 per cent social housing, those who leave are replaced by new immigrants.’

Not everyone agrees with this view. Many mention social problems, delinquency and crime. ‘This isn’t the Bronx,’ replies an indignant Benoît. ‘This is a quiet town. It’s nothing like some of the other towns around here. In 2005, during the banlieue riots, nothing happened here. There weren’t any clashes or raids.’

‘Difficult neighbourhoods? No, there aren’t any,’ confirms Yassine. ‘Everyone knows everyone here and we respect one another.’ We’re half an hour from Paris and we have plenty of advantages without any of the inconvenience. This is a cosmopolitan town that produces rappers and footballers, nothing else.’ But the local newspapers talk of drug trafficking, cannabis in particular. They say that Les Ulis has ended up on the liste rouge of problem towns and cities. They report incidents between youths and the police, as in the summers of 2009 and 2015. Paul Loridant admits: ‘Yes, there have been incidents, but never anything serious and certainly no more than in other cities in the Paris banlieue.’ As any good administrator would, the deputy mayor stresses the positive steps taken in terms of culture and infrastructure. He talks about kids from seriously underprivileged families in Les Ulis who have gone on to become university professors and leading researchers. Above all, he illustrates the current redevelopment, a genuine reconstruction to adapt the town to the demands of modern life. An ambitious project to revamp a style of urban planning that has failed to stand the test of time. A stroll around the city centre near the town hall, esplanade and market is all it takes to grasp that this is a place undergoing a transformation. Beneath the low-flying aircraft coming in to land on runways three and four at the nearby Paris Orly airport, they are working everywhere you look to change the face of Les Ulis. They are even re-cladding the towers. ‘That one there, at the bottom, near the park, the Tour Janvier, that’s where Anthony lived,’ says Jean Paul. He points to a sixteen-storey high-rise block like all the others, named after the months of the year and separated by gardens and leafless trees.

Born fifteen kilometres from here, in Massy, on 5 December 1995, Anthony is the third son of Florent and Myriam. His father comes from Le Gosier in Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe; he was born there in 1962. Florent came to metropolitan France at the age of twenty for his military service with the navy in Brest. After finishing his national service he stayed in France for two and a half years. It was then that he met Myriam, his future wife, who was also from Guadeloupe, from Petit-Bourg in Basse-Terre. Florent went back to Guadeloupe for six months but returned in 1985 to settle once and for all on the mainland. The couple married in 1986 and then moved to the Paris region. ‘We came to Les Ulis in 1988,’ remembers Florent Martial. ‘It was a young town, expanding towards Paris, near the motorways. I was working at the prefecture; my wife was working for a pharmaceutical company. Dorian, our first child, was born in 1989, followed by Johan in 1991 and then Anthony. We lived in Le Bosquet [another part of Les Ulis] and the kids all slept in the same room. Then, when Anthony was three, we moved into the Bergères Towers and they all had their own room. Of course, it was hectic at home with three boys. But they were good kids and they always felt understood. They were close as brothers. What was Anthony like? He didn’t like to be bothered. Whenever he looked at you out of the corner of his eye, that said it all. He was a bit reserved, he didn’t say much and he only smiled when he wanted to. He was very calm and collected.’

‘My brother has always had a strong character, perhaps the strongest of the three of us,’ explains Dorian, the eldest who now lives about thirty kilometres from Les Ulis and works as a technician on fire detection systems. ‘He was stubborn and there was trouble almost every day but that’s normal among brothers. Anthony is a kind person, although at school, in his own little world, he didn’t like to be annoyed.’

‘I met him at the École Primaire du Parc when we were six. We went to junior school together, then two or three years at secondary school. He was hyperactive in the classroom and a bit unruly. You could see that studying wasn’t for him. He was clever. He worked but didn’t want to spend hours with his nose in a book. He wanted to spend them with a football. I remember he was already very good when he was little. He was the only kid in Year 2 who played with the kids in Year 6. He would take free kicks like Roberto Carlos, with his left foot, even though he’s right-footed. Who were his idols? Ronaldo, the Brazilian Ronaldinho, and Zidane. He supported Olympique Lyonnais, the team that was winning everything in France back then. But he also liked Guardiola’s Barcelona. The first shirt he had was Sonny Anderson, the Brazilian striker for Les Gones [OL’s nickname, meaning ‘The Kids’ in Lyon’s regional dialect],’ remembers Fabrice Tenin, nicknamed Pépère. With his brother Baptiste, nicknamed Titoune, Pépère was one of Anthony’s best friends.

‘The Tenins were our neighbours in Les Ulis,’ remembers Florent Martial. ‘Anthony was always at their house. Mimose, their mother, thought of him as one of her own. She would cook his favourite dinner, chicken. Still now, even though we don’t live in Les Ulis anymore, whenever he comes back to Paris, Anthony almost always goes to see her first.’

‘Life’s changed today. The city’s changed and society’s changed,’ continues Tenin. ‘We have generation 3.0 now, PlayStations and mobile phones, but when we were small, we had a ball. We never stopped playing with it. We would spend whole days playing on the elevated section, on the cement walkways or on the little pitch down there below Anthony’s tower. It was a grass pitch with goals and nets that were changed twice a year. Our parents could keep an eye on us and call us in for dinner from the window.’

Who taught Anthony to play football?

‘His father and his older brothers. I would see them playing on Sundays sometimes, on the pitch under the tower.’

‘Yes, it was our dad who passed on his passion for football to us,’ explains Dorian. ‘He played in an amateur team in Guadeloupe when he was young.’

‘I was an attacking left winger for AS Gosier,’ Florent confirms. ‘I started playing when I was fourteen and stayed until I was twenty. I could have played in the CFA amateur league but then I left to do my military service.’ He adds: ‘In those days, I was a Marseille fan but now I support Troyes [the team in which Johan plays] and Manchester United.’

‘I’m not surprised that he made it from Les Ulis to United. He’s a chilled-out guy, quiet, with a great character. He hasn’t let it go to his head. Last year’, continues Tenin, ‘I went to Manchester to visit him with Baptiste, my brother, and Anthony’s parents to celebrate his twentieth birthday. I have to say, he hasn’t changed a bit. He’s still the same as he was when we played at school.

What has he left here in Les Ulis?

Françoise Marhuenda, Mayor of Les Ulis, explains: ‘His success has given people courage. He passes his values on to young people and proves that anything is possible, that when you want something you can succeed. He’s also passed on his sporting values: tenacity, respect, citizenship and fair play, everything that is also important in everyday life.’

‘His example has undoubtedly had a positive impact. He’s left a powerful mark,’ Tenin concludes. ‘Kids start playing football by following his example. But he’s also left a legacy that will be hard to take on. So many dream of becoming like him, but there’s only one Anthony.’

Chapter 2

In the footsteps of Henry and Evra

A big grey box next to the running track in the Stade Jean-Marc Salinier. Outside, on a dark winter’s evening, it is cold and foggy, but right at the end of a synthetic pitch, beneath the floodlights, a group of children has just started training. Inside, a yellow light is on and people are constantly coming and going. Boys and girls with bags slung over their shoulders enter the brand new clubhouse, on their own or accompanied by fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters. They politely say ‘Bonsoir’, shake hands with the directors, coaches and casual visitors before going to get changed in the dressing rooms next door. The club’s first rule is to be courteous and behave properly, greeting everyone with a smile. ‘They don’t have to make an effort. They do it willingly. They’re smart,’ says Jean-Michel Espalieu, Vice-President of the Club Omnisport Les Ulis, Football Division.

Talking as he sits behind a long table, he is trying to look after a little girl who has no intention of sitting still, even for a second. The gaze of the person he is talking to shifts from the little girl, who has now gone in search of some coloured pencils, to the yellow walls: a gallery of memorabilia and a parade of champions. There’s a white Manchester United shirt with the number 9, worn by Anthony Martial; the number 14 blaugrana Barcelona shirt worn by Thierry Henry; and Patrice Evra’s black and white striped number 33 Juventus shirt. These hang next to the club’s blue and white flag, against which the colourful pennants of other clubs stand out: AS Poissy, Olympic Hallennois, PSG, Racing Club de Lens, Le Mans Union Club, Inter Milan and Borussia Dortmund. There are more shirts in blue frames: from Coulibaly to Johan Martial, from Sanogo to Evra’s Manchester United shirt, and, at the end, Anthony’s number 23 Monaco shirt. This is where the Manchester United striker began playing football seriously, here on Avenue des Cévennes in Les Ulis. An association formed at the same time as the town, in 1977, has since become the Club Omnisport. It now boasts 28 disciplines (from aikido to hockey, from archery to boxing) and 4,200 members. The lion’s share of those are there for the football. ‘We have 830 members, almost three per cent of the entire population of Les Ulis. We are the third largest club in Essonne,’ explains Espalieu. ‘Evry is the largest, with 1,200 members, but that’s only two per cent of the town’s inhabitants. Every category is represented: we go from the Under 6s to the veterans, from five-year-olds to 35-year-olds and beyond. We also have a women’s section that’s booming, with 45 ladies. From Under-6 to Under-11 level our club is considered one of the best in France, and not just by us. Three years ago we renovated this clubhouse, converted an old red clay pitch to synthetic and built another. Now, to accommodate all our players, we have a sports complex (two grass pitches, three synthetic pitches, an athletics track and twelve dressing rooms) that is in keeping with our ambitions.’

Besides their facilities, what marks the club out, they say around town, is its family feel and that it spends a significant amount of time working with local kids at grass roots level. ‘We don’t set technical priorities, we accept anyone at any time of year. What prevails here are educational and social goals. Our priority is to train the kids, to get them to have fun and stay away from the troubles of the banlieue,’ says Mahamadou Niakaté, who interrupts his long conversation with an impeccably dressed broker on the other side of the table to have his say. Niakaté, aged 37, has been responsible for the football school since 1987, while also coaching the senior team and playing for the veterans. He insists: ‘Just by way of an example, I can tell you that four years ago we had university tutors come to the club to help the kids who were struggling at school. Even if there are parents who enrol their kids believing that in the blink of an eye we’ll transform them into champions capable of earning piles of money, we’re not here to create professional footballers.’ Whatever the case, the results of this instructional club speak for themselves: as well as Thierry Henry and Patrice Evra, its alumni include Yaya Sanogo (formerly at Arsenal and Crystal Palace, now at Charlton Athletic) and Jules Iloki (FC Nantes), to name only the most famous; more than ten youngsters from Les Ulis have gone on to become professional footballers. Henry, the former Gunners striker who had spells at Barcelona, Juventus and Monaco, France’s all-time leading goal-scorer and now a commentator for Sky Sports, was born in Les Ulis in 1977 to West Indian parents, just like Anthony. He started playing at the club when he was six, before moving to US Palaiseau in a neighbouring town at the age of twelve. He has kept up his ties to the city and, with his One 4 All foundation, has contributed more than €200,000 to funding a seven-a-side synthetic pitch in the Bosquet neighbourhood.

‘Patrice is a friend,’ explains Niakaté, who played alongside both Henry and Evra. We know him better as a person than as a player. Although he was only with us for a season, he still helps us. He sponsored the senior team, bought strips and sports equipment and, when he was playing in the Premier League, he invited 40 of our kids to watch a game at Old Trafford. He also donated his bonus [€27,000] from the 2010 World Cup, which was marred by the players’ revolt in Knysna.’

Neither Henry nor the France and Juventus defender spent a great deal of time on the club’s pitches, unlike Anthony; it is obvious the directors have a weakness for the kid from the Bergères Towers. It is clear for all to see in the team photos from when Martial was about seven, or the little shrine dedicated to him with the front page of L’Équipe of 25 September 2015 on display. It shows a full-page photo of the number 9 with the title ‘Épatant Martial [Stunning Martial]’ and a paragraph that recalls:

‘The French striker whose record transfer was so controversial has a thundering start to the season. Four goals in four games for Manchester United and a popularity rating that is already sky-high in England.’

No one in Les Ulis has forgotten the first few weeks of that September. ‘It was the only thing we were talking about here, and everyone was following the story minute by minute on tablets, phones, Facebook, social networks and websites,’ confesses Aziz Benaaddane, the technical director and Under-17 coach who joins in the conversation after arriving late. ‘I have to say that we weren’t particularly surprised by the news of his transfer. We’re used to seeing our kids go to big teams. What we were struck by was the amount United paid. Although I’m convinced the boy is worth it and is a great investment for the future.’

Value judgements aside, they were intense days for the club. It was literally stormed by the French media. When they found out about the figures involved, troops of reporters arrived from anywhere and everywhere. It was a frenzy. Cars and vans from radio and TV companies invaded the car park. The directors’ mobile phone voicemails were clogged with requests for interviews from Norway to Japan.

‘We responded to everyone. We must have given more than 50 interviews and even ended up live on the TF1 news,’ remember Niakaté, who was struck by the curiosity of the English media who turned up on the first Eurostar. ‘We were still here at the stadium at ten o’clock at night speaking to them, and the next morning I found them outside my house as they were going to Anthony’s old junior school. They wanted to know absolutely everything about Martial’s life.’ They were keen to learn as much as possible about the Golden Boy. They were also curious to know how Les Ulis would use the €250,000 it would get from Martial’s transfer, as the club that trained him from age twelve to fourteen. It was a jackpot that was almost the equivalent of the annual budget of the club on Avenue des Cévennes. ‘We bought four minibuses with the first €100,000 to give us some independence when playing away matches. We will invest the rest in new instructors, in their training, in educational materials and sports equipment. Nothing crazy. We don’t recruit people at top dollar, none of our players has a federal contract [the equivalent of a professional contract for amateurs] and our first team staff also coaches the kids. We don’t want to get ideas above our station,’ says Benaaddane.

The €250,000 also made the Martial family happy. ‘Les Ulis is a club that is close to our hearts,’ Johan Martial told Le Parisien ‘Our story started here and it’s thanks to the club that we’ve come this far.’

‘I’m happy that they’ll get such a sum,’ explained Florent. ‘The instructors here do a fantastic job. When he was younger Anthony could be a bit temperamental … But they looked after him.’ They began looking after Anthony at Les Ulis in the autumn of 2001.

‘Dorian was the most motivated of the three brothers. He wanted to play football and I took him to Les Ulis, then Johan followed. As his big brothers were playing, Anthony wanted to do the same and he started when he was five, a year before the minimum age group. With him it was all about football, he wasn’t interested in other sports. I wouldn’t say that he had anything special straight away. It was as time went on that we began to see his aptitude. From Under-11 tournaments and up,’ Mr Martial senior explains.

‘I always wanted to be a footballer. I never thought about doing anything else, it’s what I’ve wanted from a very young age. I remember my very first training session,’ recalls Anthony. ‘It was raining heavily and it was cold. I trained for ten minutes and then I told my dad I wanted to go home.’

Niakaté, his coach, explains: ‘No, I don’t remember that first time but I haven’t forgotten that he would come with his dad to watch his brothers’ matches when he was tiny. He followed their example. Johan played here for two years before going to Paris Saint-Germain. Dorian still plays here, in the seniors. He’s a great guy, a good defender, a number 5 that I sometimes put on the right wing even if it makes his father angry. He was never bothered about going to see the professional clubs, but he’s still been successful. He’s in love with the ball. He travels 30 kilometres a day to come to training.’

Benaaddane goes on to say: ‘The Martials are simple, quiet people. It’s never gone to their heads. When Johan signed for Brest they didn’t go mad. And they haven’t changed since Anthony signed his million euro contract. They’re not about the bling, fast cars or huge mansions. They did leave their apartment here in Les Ulis but they moved a few kilometres away to Saint-German-les-Corbeil, to a simple single-family house. Florent is a football fan. Often on Sundays he comes to watch Dorian’s matches when he could be in the stands at Manchester United. The mother is a lovely, kind lady and, with a football-mad husband and three sons, she had no choice but to take an interest and she gradually started to like it. His mother and father gave Anthony a very strict upbringing because the boy could be temperamental.’

‘Stubborn, determined, proud, shy, sometimes grumpy and very reserved. He was a child who didn’t speak much around adults,’ says Espalieu. ‘He was much more expansive with his teammates though, he liked to joke and laugh. He was well-liked by everyone, which isn’t easy because the best player in the team is not always popular. He was though. He was liked by those who played with him. They respected him for what he could do with the ball at his feet. And they stuck together. I’ll tell you about the time when Anthony left his kit bag at home, with all the things he needed to have a shower. We told everyone that if they forgot it, they couldn’t play. Martial shouldn’t have been on the pitch for that game. But his teammates came to see me one after the other. Some offered to lend him soap, others shampoo or a towel. They knew it wouldn’t be easy playing without him. So, we had to say OK then, but this is the last time.’

‘At age six, most of the kids do “pre-training”. They have fun, play, wander off to count four-leafed clovers around the pitch. Anthony was different,’ explains Niakaté. ‘He knew about football. He knew what a football was. He already had a good understanding of the basics, but he didn’t give himself airs and graces,’ remembers Wally Bagou, who had him for two years in the Under 7s and Under 13s. The instructor has just finished training the youngest children. He has come back to the clubhouse for a chat and to warm up. He sits down and says: ‘On the pitch, he wanted to win at all costs and when his team lost he was uncontrollable. He would get angry and sulk but he wouldn’t cry. He was tough. He was magnificent.’

‘My first memory of Anthony? He must have been six,’ remembers Benaaddane. ‘He took the ball in his area and went on to score, leaving his opponents in his wake. We had 400 kids but a talent like him was rare.

‘No one thought he would be a professional, a champion, but you could see from a mile away that he had some interesting qualities and great potential,’ explains Niakaté. ‘He reminded me of Henry: he was an intelligent goal-scorer, fast, elegant and decisive. We kept an eye on him. We tried to spur him on to get the best out of his potential.’ And … let’s just say they had to push him to work seriously because training and drills were not his forte. They were too much effort. But when it came to playing, he always had a smile on his face, thanks to the stimulus given by his instructors and his desire to improve, as well as a determined character and the talent of a child who took no time in making huge steps forward. He always jumped ahead to the next category: from the débutants (Under 7s) to the poussins (Under 11s), from the poussins to the benjamins (Under 13s). He always ended up playing with the bigger kids.

Chapter 3

The meeting

His name appeared at the bottom of the list, written in pen in the eleventh position. It came after Hapt, Laidoi, Benhassine, Zayed, Dieye, Grosy, Kabral Bissi, Bathily, Azurmendi and Khouildi. The licence number was 2318054571. His date of birth was wrong: 30/12/1995. It would have made him twenty-five days younger than he was. Anthony was the only one born in 1995; his teammates were born in 1993 or, like Deyne, Irwin, Tarek and Mousur, in the first half of 1994. The list, which was filled out and given to Nadine Bernard with the corresponding photographs, was the Les Ulis B team registration form for the Tournoi International Benjamins de Gif-sur-Yvette, an Essonne town with 20,000 inhabitants, three and a half kilometres from Les Ulis.

In 2004, the powers that be at OC Gif Football, the town’s sports club, came up with the idea of ‘allowing children from the region’s clubs to enjoy an unforgettable experience as part of a festival of football,’ to quote the tournament brochure. Although the event was limited to local teams in its first year, in its second year, Philippe Renard, the logistics manager, and Pierre Durand, responsible for the technical side of the tournament, had bigger ambitions and decided to extend participation to national and international clubs. Durand, then a recruiter for RC Lens, invited friends and acquaintances to bring their teams to the tournament, for boys aged between eleven and twelve. This appeal was answered by fifteen clubs from Essonne, six from Île-de-France, four from other départements and three professional clubs: Rennes (Ligue 1), Créteil and Reims (L2). But someone dropped out at the last minute and they needed to find a club to fill the final spot in the 32-team draw. ‘I picked up the phone and called Aziz Benaaddane,’ remembers Durand. ‘I asked him if they could get a second team together to take part in our event.’ The answer was yes, hence the Les Ulis B team list on which, aged barely nine and four months, Anthony Martial appears. He was two years below his category, surclassé as the French say. On 31 April and 1 May 2005, 500 children took part in the ‘festival of football’ at the Parc Municipal des Sports Michel Pelchat. Olympique de Saint-Étienne won the tournament, beating Evry in the final.