9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

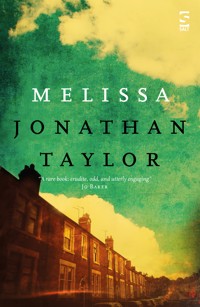

Shortlisted for the 2016 East Midland Book Awards Melissa is set in 1999-2000. At roughly 2pm on 9th June 1999, on a small street in Hanford, Stoke-on-Trent, a young girl dies of leukaemia; at almost the same moment, everyone on the street experiences the same musical hallucination. The novel is about this death and accompanying phenomenon – and about their after-effects, as the girl's family gradually disintegrates over the following year.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Melissa

Shortlisted for the 2016 East Midland Book Awards

Melissa is set in 1999-2000. At roughly 2pm on 9th June 1999, on a small street in Hanford, Stoke-on-Trent, a young girl dies of leukaemia; at almost the same moment, everyone on the street experiences the same musical hallucination. The novel is about this death and accompanying phenomenon – and about their after-effects, as the girl’s family gradually disintegrates over the following year.

Praise For This Book

‘Melissa is an intricate kaleidoscope of a novel that explores the inevitable decay of bodies, of houses, of minds and of families. And the unexpected beauty of what comes after.’ —Jenn Ashworth

‘Melissa is such a successfully ambitious book that riffs and ranges through medicine, mathematics and music. It’s a flight of darkly comic fancy that takes off from the solidity of a Midlands housing estate and fires its satiric barbs at every form of society’s cant. It’s reminiscent of a Burslem Beckett.’ —Desmond Barry

‘A rare book: erudite, odd, and utterly engaging.’ —Jo Baker

Reviews Of This Book

‘éééééMelissa avoids the sensational, sentimental, and over-emotional traps and offers an unblinkered view of a family trying to make sense of tragedy. So far, it’s rather like Carys Bray’s A Song For Issy Bradley, but whereas the Bradleys for all their differing opinions behave as a family, the Combs lack that cohesion and act as individuals, each filled with frustration, anger and grief. Melissa is definitely a darker yet quirkier read.’ —Our Book Reviews

‘This is an impressive novel, which successfully captures a wide range of themes and ideas. To me, while reading Melissa, I imagined the central story of the hallucination as the trunk of a tree while the aftermath on individual characters were like branches, heading off in different directions but always coming back to the central idea.

One of the reviews from the back cover of the book calls Melissa ‘an intricate kaleidoscope of a novel’ and I totally agree. This really is a must read, and deserves lots of readers.’ —Writer’s Little Helper

‘I thought Melissa was an intriguing, at times heartbreaking, read. It was at times scathing about modern life, at times brave about the human condition. It’s well worth a read, enjoyable and engaging.’ —Books from Basford

Praise For Previous Work

‘Original, strange, funny, profound.’ —Louis de Bernières

‘Entertaining Strangers made me laugh. If you are interested in landladies, eccentrics, philosophers, bad families, music, degenerates and ants, Jonathan Taylor’s entertaining and illuminating novel will make you laugh, too’ —Kate Pullinger

‘Gripping tale of deeply strange and obsessive characters, funny and horrifying, a great read.’ —Michele Hanson

‘A literary novel with prose like music. A novel that demands a reader response … A novel that deals with the crunchiness of living life on the edge.’ —Sophie Duffy

‘… an intriguing … investigation into the inescapability of personal and political history … many things to admire.’ —Times Literary Supplement

‘This quirky tragicomic novel … is a spiritual boost for the soul that reminds us of the importance of altruistic gestures …. It provides a great many laughs as well as a few surprises along the way.’ —Spirit & Destiny Magazine

‘… contender for best book of the year …. The poetic prose is witty and sharp …. Entertaining Strangers is an intelligent, funny and tragic book …. Highly recommended.’ —Jessica Patient, The View From Here Magazine

Melissa

JONATHAN TAYLORis an author, lecturer and critic. His books include the novelEntertaining Strangers(Salt, 2012), and the memoirTake Me Home: Parkinson’s, My Father, Myself(Granta, 2007). He is editor of the anthologyOverheard: Stories to Read Aloud(Salt, 2012). Originally from Stoke-on-Trent, he now lives in Leicestershire with his wife, the poet Maria Taylor, and twin daughters, Miranda and Rosalind. His website iswww.jonathanptaylor.co.uk.

Also by Jonathan Taylor

FICTION

Entertaining Strangers(2012)

SHORT STORIES

Kontakte and Other Stories(Roman Books, 2013 and 2014).

NON-FICTION

Take Me Home: Parkinson’s, My Father, Myself (Granta Books, 2007)

ANTHOLOGIES

Overheard: Stories to Read Aloud(2012)

POETRY

Musicolepsy(Shoestring Press, 2013);

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Jonathan Taylor,2015

The right ofJonathan Taylorto be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2016

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-058-4 electronic

‘Every disease is a musical problem. Every cure is a musical solution.’

–NOVALIS,Encyclopaedia

Dedicated i.m. to Eric Leveridge

Inspired by true events

1st Mvt:Musica Mundana

PRELUDE

The Spark Close Phenomenon

THE REAL TRAGEDY,of course, happened before the story begins – seconds before. At 2.35 p.m. on Wednesday 9thJune 1999, in Number 4, Spark Close, Hanford, Stoke-on-Trent, Miss Melissa Comb, a seven-year-old girl, died of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia in her own bed, surrounded by family and nurses.

What followed has been floridly described by Stoke-on-Trent’s Poet Laureate as a ‘musical efflorescence of grief’ for the dead girl. This ‘musical efflorescence’ has been raked over endlessly, by poets, journalists, priests, neurologists, psychologists and parapsychologists. Some have called the ‘Spark Close Phenomenon’ a musical form of mass hysteria, others a kind of telepathic psychosis, others a millennial judgement on our modern way of life. If none agree in their interpretations or conclusions, a general consensus has emerged about the actual events of that strange afternoon.

Moments after Melissa’s family watched her die next door, sixty-six-year-old Mr. Paul Higgins, ex-Open University lecturer, part-time columnist, part-time right-wing radio broadcaster, of Number 6, Spark Close, was hit by what he later called, in various newspaper interviews, a “ringing, hum-dinging headache.”1 He had been dozing, he claimed, with a packet of beef and onion crisps in front of TV insolvency adverts, when he jerked awake, and – as he put it later – the “screen seemed to, like, dissolve in front of my eyes.” This was accompanied by an “alarm-ish noise, like some deafening bell ringing in my head. I suddenly felt awful, sicketty-sick. I got off my arse, and – I can’t explain it – I felt kinda forced to walk to my front door. I couldn’t hardly see anything, and, as I say, there was this huge alarming going off in my head. So I staggered to the door, opened it, and stepped out onto the street. As soon as I was outside, the ringing faded away, and was kinda drowned out by . . . well, by music. Classicalist stuff – y’know, orchestra and violins and all that malarkey. It was dead loud at first. But gradually, it faded away, over the next few minutes or so. It was while it was on the way out I noticed all the doors in the Close were opening – everyone was coming out, holding their heads or ears like what I was.”

Mrs. Hayley Hutchinson, and her out-of-work grandson, Frank, of Number 8, Spark Close, were certainly holding their ears: “The siren we heard, it was something out of the war – an air-raid siren raiding my head, if you see what I mean. Came out of nowhere. Goodness me. We thought it was the TV, and Frank here, my grandson (who’s a bit of a dab hand with technical stuff), went and whacked it. Then he switched it off at the plug. But the siren carried on with the TV off. I was almost crying, and Frank, well, he was a bit of a hero. Always knows what to do. This time, he dragged me out of the house into the street – as if it was a different kind of air-raid siren, telling you to go outdoors, not in.

“Suddenly, or perhaps it was gradually, the air-raid siren noise stopped, and instead came this music – like what they play at the Cenotaph, you know. Kind of beautiful, slowish, saddish, yet . . . stirring. Brought a tear or two to my eyes, I don’t mind admitting. Like England – but nicer, like in the 1950s, fields and cowpats, you know, and not everyone robbing everyone else. Like when we were in and out of each other’s houses down this Close all the time. I couldn’t understand why the music was happening, but I was relieved the sirens had stopped. So was Frank. He was standing to attention, next to me, as if on parade. He was in the Territorials, you know, till two years ago.”

Frank himself commented: “That music, it made me think back to my time as a soldier, and I felt like presenting arms, or saluting someone or something. Well, I suppose nothing much’s happened since then to think back to instead. So I felt eighteen again, like I’d gone back three years into uniform, and the flag was waving and we were supposed to be commemorating something. Without a flag there to salute, I saluted Ms. Kirsten from Number 10instead. She was wearing a bikini top and shorts – they were Union Jacks, so it was almost as good as the flag. My grandma told me to stop gawping. But Ms. Kirsten didn’t see me anyway – or, at least, seemed to be not looking quite at me.”

Ms. Kirsten Machin, divorced mother of twin boys, of Number 10, Spark Close, had been out in the back garden. Her statements to the press, doctors and police have been rather confused, if not contradictory. In the immediate aftermath of the Phenomenon, she appeared distracted, and incoherent in her speech when approached by the emergency services. This has led to some fairly wild speculation about the part she played on the day. It has been pointed out that she owns a powerful stereo, and has a taste for playing anti-socially loud music – sometimes, according to one neighbour who will remain nameless, in a bid to “drown out the babies’ screams.” At least one tabloid commentator has suggested that the whole Spark Close incident might be explained by Ms. Machin’s (and I quote) “huge woofers.” The simple fact that Ms. Machin’s woofers were not accustomed to blaring out orchestral music seems to have escaped this particular commentator. Moreover, the nature of what happened that day on Spark Close, and the testimonies of the many witnesses, all point up the inadequacy of such a facile explanation of events.

Another tabloid explanation of Ms. Machin’s behaviour that afternoon is potentially defamatory, and hence cannot be repeated here – sufficed to say, it involves a sun-lounger, a bottle of gin, and twins screaming from an upstairs room. Roughly two minutes after Melissa Comb’s death at Number 4, Mrs. Machin seems to have fallen off her sun-lounger: “I got this huge fuck-off pain walloping me on my head – worse than having twins in your brain, if that’s possible. Jesus help me, I thought, my brain’s going to explode. And then there was the banshee shrieks – out of fucking nowhere. At first, for a tiny second, I thought it was something in the Close, perhaps someone being hacked to death next door. But then I realised it was in my head. In my head, for Christ’s sake. I wondered if this was like . . . what’s it called? . . . tiny-tuss, tinny-tits, tissy-tinnies . . . anyway, whatever, that whistling-ringing thing you get in your ears. Or perhaps all those years when I was young-ing it up in the clubs were coming back to haunt me. Fucking hell.

“The babies were haunting me as well, I can tell you. I could hear them screaming outside my head, as well as the screaming inside it. I was only out in the back garden for a few minutes – you know, they’d . . . gone off for their afternoon nap. I’d never leave them otherwise, course not. Always make sure the baby monitor’s there, right next to me. Anyway, the babies’d started shrieking at the same time as my head was inside-exploding, like. The two shrieks were getting all mixed up, and I couldn’t even stand up straight. I was fucking terrified.

“But, you know, a mother’s first thought is always for her kids, isn’t it? So I pulled myself to my feet, and legged it into the house. The noise didn’t get louder or softer there. It was just like there, in my head, the same wherever I went, whatever doors I opened or closed. I thought I was going Looby-Lou. Except that, if I was going Looby-Lou, so were the babies. I guessed almost without thinking that p’raps they had the noise in their tiny heads too. So I ran up the stairs to them, two at a time. When I’d go to the top and un . . . opened their bedroom door, I found them bawling their eyes out, filling their cots with tears, poor sods. Hysterical, like. I scooped them both up at once, and belted it back down the stairs, and out the front door. I couldn’t tell you why I went out the front door. It’s not like I was looking for help. Wouldn’t expect any help from those knobs-I-don’t-call-neighbours. But my feet and the noise in my head carried me out the front door whether I liked it or not.

“That was when the shitty shrieking in my head stopped dead. Then . . . then came this other tune, out of nowhere, kind of creeping up on me, or us, if you count the babies. Dunno how to describe it. Like Mantovani and all that old shit me dad used to like. But not, if you know what I mean. More classy. I tell you what was awesome about it: suddenly the babies were dead quiet too. First time all sodding day. All sodding day . . . Well, yeah, course, except for that bit when they had a nap, obviously. Might try some of that classical shit on them myself. Worked a treat. Classical Calpol. I sat down on the doorstep with them on my lap, and we all listened inside our heads – if you know what I mean.

“That was when I looked up, and saw all the others – all the knobs-I-don’t-call-neighbours – round the street, coming out of their houses too. People like that old bitch from next door, her with the crumpled-up face, and that weird tattoo on her arm. Horrid, faded thing – I mean, the tattoo . . . God, I’ve got a fucking dragon with its tail down my arse. All she’s got are some crappy grey set of numbers on her arm. Rubbish. They obviously didn’t know how to do tattoos back in 1066 or whenever.

“I tell you what, they didn’t know fuck all back then about music either. It’s her who’s always complaining to the Council about my stereo. Complain about anything, that one, from my music to the rain to the fucking sunshine – probably her who told the newspaper it was me who was to blame for the whole thing. Miserable bitch.”

The so-called “miserable bitch next door” was Miss Rosa Adler, a seventy-five-year-old pensioner, who was the first to alert the emergency services. Whilst her neighbours were gathering in the Close, she initially resisted the urge to step outside, instead dialling 999.

There is an extant tape of the 999 call, recorded at precisely 2.39 p.m., in which Miss Adler is heard whimpering: “Make it stop, make it stop, please please make it stop, do something, it’s here, Spark Close, it’s in my head and everywhere,schnell, makeitstopmakeitstopmakeitstop,” over and again. The call-handler attempts to calm her and make sense of the call, but in vain: “Which service do you need, miss? Is there an incident you want to report, miss? Is the incident at Spark Close, Hanford, Stoke-on-Trent?” In response, Miss Adler is heard sobbing something incomprehensible, followed by the peculiar and unexplained words: “No, it’s not Spark Close. It’s climbed back inside my head. TheMädchenorchester. It’s got back in there, and won’t stop . . .Aufstehen!. . . ” Then there’s a distant shriek on the recording, as if from somewhere else in the room; and the call-handler is left asking: “Miss? Are you still there? Miss? Can you tell us what is going on?,” with no further response from Miss Adler.

Miss Adler later told the police that she abandoned the phone under an irresistible compulsion to go outside, and “feel the sun on her dwindling hair,” as she put it. “Ah, it was beautiful outside – the sun, it was shining, and everyone was milling about, even smiling at each other, like the street used to be in times when my hair was fuller and darker. 1977 and all that – how do you say? – jazz. But no, I couldn’t smile or . . . ‘mill’ with them. I couldn’t even enjoy my sunny hair, because there was this . . . this terriblefortissimoin my head. I have no doubt everyone thought I was being glary and unfriendly at them. But it was not true. My glaring, it was really directed inwards. I was glaring in my head, trying to shush the inside-orchestra. But instead ofdiminuendoing, it wascrescendoing all over. Strings, wind, timpani, trombones, everything. Stop it, I kept telling my head. Stopitpleasestopitmakeitstop, but it wouldn’t listen.Ihad to listen toit,itwouldn’t listen tome. Like that silly Miss Kirsten who lives next door, with her bang-bang music and bang-bang arguments and bang-bang . . . well, those other activities, shall we say. Babies screaming, men coming and going and shouting, you wouldn’t believe. She says I go on about it, but what can you do when you’re woken up at three, four in the morning? And I worry about her, I really do. She thinks I don’t understand – that I know nothing about what goes on, about sex – that I can’t help with the babies, the men and so on. I mean, where does she think my own son came from? And who else knows more than myself about how it’s like being what they now call a ‘single mother’ – and what they used to call many other things? Honestly, what can you do to help someone who doesn’t want to be helped?

“Anyway, I am getting away from the subject. At first, I thought it must be her, Miss Kirsten, when the music started. I was washing the dishes, and I thought it was coming through the walls, through the floor, through the windows. But then I realised that the walls, they weren’t bouncing as usual. No, it was the walls of my own head that were bouncing. It wasn’t like her music. Music sounds all the same to me these days, all horrid, but even I could tell this was different. It was . . . it was old-fashioned – horrid-old-fashioned, as horrid-old as my memories.”

Miss Adler is the only witness of the Spark Close Phenomenon for whom the “horrid-old” music was not preceded by some kind of screeching or “alarmish noise.” She was also the only witness for whom the music started before she stepped outside the house. She did, though, share with other residents the same peculiar compulsion to leave her house by the front door; and she clearly found the music in her head as disturbing as others found the preceding screeches, sirens or alarms. Whereas others were comforted by the onset of the “old-fashioned” music, which generally superseded these “screeches,” or “alarms,” she found it hateful.

No convincing explanations have been proposed for the differences between Miss Adler’s experience and that of other residents, the majority of reports focussing on the collective experience of the Phenomenon, rather than analysing exceptions.

Another exception was Miss Rosa Adler’s neighbour, Dr. Terence Williams, who lived in the only detached house, Number 14 at the end of the cul-de-sac, and who never ‘reached’ the musical stage of the Phenomenon. Dr. Williams, a fifty-year-old ex-GP on incapacity benefit, reported hearing a screaming noise at 2.39 p.m. He glanced at his wall clock when it started, and made a mental note of the time, “in case the information would be of use later – you know, for a case study, journal article,et cetera. I thought it was one of my seizures, and I always try to remember what happens in the lead-up to them. But looking back on this seizure, or whatever it was, I can’t remember much at all after the clock loomed out of the wall at me. After that, everything was blotted out by the noise. It was horrible, hellish, a gnashing of teeth in my head, amplified a thousand times. All I knew, all I could think of was that I had to get out of the front door.”

Unfortunately, Dr. Williams suffers from temporal lobe epilepsy, and he collapsed on his own ‘Welcome’ mat before he could get outside. He was found twenty minutes later by medics, unconscious, cyanotic, hugging his legs, in a pool of saliva, urine and blood. From the evidence available, it would seem he had experienced a full-blown seizure as he was attempting to push a key into the lock on the inside of the front door. One trainee paramedic who found him reported that there was a noticeable dent in the door frame, making it look like he had repeatedly head-butted the door during the seizure, “as if his head was trying to escape any way it could.” The paramedic’s colleagues on the scene would not verify this claim, declaring that it was not their priority to contribute to media speculation, only to help the injured and distressed.

But in this, the emergency services were at a bit of a loss when they first arrived, given that the majority of the people who experienced the Spark Close Phenomenon were neither injured nor distressed. Prior to their arrival, indeed, most people were visibly enjoying themselves. Ms. Kirsten Machin, for one, was uncharacteristically serene, sunning herself on the doorstep and holding gurgling twins on her lap, who (it would seem) had been lullabyed into half-sleep by the music in everybody’s heads; Mr. Frank Hutchinson was standing to attention, saluting, and now and then surreptitiously pulling faces at the twin babies when his grandmother wasn’t watching; Mrs. Hayley Hutchinson was standing like a tear in an eye, lost in a Remembrance Sunday reverie. All round the close, people were emerging from their homes into sunshine – at first clutching their ears in agony, and then straightening, loosening, as the inner-music seemed to suffuse their very muscles, bones, marrow. Mr. Rajesh Parmar from Number 9, the Shelley sisters at Number 5, fourteen-year-old Elizabeth (‘Lelly’) and seventeen-year-old Davy Lawson from Number 3 (both of whom should have been in school, but weren’t), the entire Runtill family from Number2 – all of them burst out of their houses, bent double, hands over their ears, then gradually softened, stood up, listened, brightened. All of them waved and smiled at their neighbours. Even Ralph, the ownerless cat who squatted at Number 1, was seen sitting on an outside windowsill, head to one side, raising a paw in greeting. For a few minutes, the music seemed everywhere, in everything and everybody.

It had spread like a mini-tornado, in a near-complete circle. Within a minute of Melissa Comb’s death at Number 4, Paul Higgins at Number 6 was the first to hear the screeching, followed by the unexplained music; a minute or so later, it had spread to Numbers 8 and 10; at roughly 2.38 p.m., Miss Rosa Adler at Number 12was afflicted by the inner-music, and, at 2.39 p.m., she dialled 999; simultaneously, Dr. Williams from the end of the cul-de-sac heard “hellish gnashing” in his head; then, between about 2.40 p.m. and 2.45 p.m., the musical cyclone circled round to the left-hand (or south) side of the Close, affecting in turn Rajesh Parmar at Number9, the Shelley sisters at Number 5, and Lelly and Davy Lawson at Number 3; and finally, the cyclone turned the corner again, to hit the Runtills’ household, Number 2, on the right-hand side of the close, next door to the dead girl. Estimates vary, but the general consensus is that the Runtills emerged from Number 2, Spark Close at approximately 2.47 p.m. (For a schematic plan of the Close and its residents, see Fig.1).

Fig 1. Spark Close residents in June 1999

Meanwhile, no-one at Number 4 heard anything. Number 4was the silent centre of the musical storm – at this point, the still centre of the story. No-one there so much as looked out of the window, to see what was going on in the Close. All the living who were present in Melissa’s bedroom at the time – including two Macmillan nurses, Mr. Harry Comb, Mrs. Lizzie Comb, and Harry’s eldest daughter, seventeen-year-old Serena – have been asked over and again whether they experienced any aural disturbances that afternoon; and they have all repeatedly denied hearing anything. Indeed, Melissa’s half-sister Serena has gone so far as to testify to the neurologist investigating the case that those few minutes were, for her, the “silentest moments of my whole life so far. When I remember those moments, it seems as if we were kind of . . . sound-proofed from the world outside. The silent moments went on so long, I started thinking silly things – like perhaps poor Mel had taken my hearing with her, and I’d never hear anything again . . . or at least never hear anything right again.”

In the whole of Spark Close that afternoon, the people at Number 4 were alone in their silence. Everyone else on the Close that day experienced some kind of vivid musical ‘hallucination.’ Bizarrely, this ‘hallucination’ also spread beyond the confines of the Close, to residents who were at work, or away at the time. Mrs. Sejal Parmar, wife of Mr. Parmar of Number 9, Spark Close, was working in a British Gas call centre half a mile away, and reported that she “heard strange interference on the incoming line. It was during a call from a man from Sunderland. At first, I thought it was the ‘hold’ music mixing itself up with the callers, you know? But it was so . . . strong, not like the electrical pingy-pongy music they normally use. And I felt it was coming not from the head-piece, but from inside my head – from memories or dreams I couldn’t remember. Beautiful, it was, caring music, you know? – something like mothers. I can’t explain it in words, and I can’t explain why I started to cry, or why I feel like crying now I’m talking about it. I mean, it didn’t last long, and then I was talking again to the man from Sunderland, who was very cross. He was much louder than the quiet music, and drowned it out, you know?”

The residents who were not on Spark Close that afternoon, but who experienced “echoes” of the musical hallucination from a distance, all reported that the music sounded “quiet,” as if overheard from afar. By and large, their experience of the Phenomenon was less intense than the people who were on the scene. Nonetheless, their testimonies are valuable, if only because they controvert the arguments of those who put forward overly simplistic explanations of the Spark Close Phenomenon. For example, it would clearly not have been possible for Ms. Kirsten Machin’s stereo to have been heard in a call centre half a mile away. Any credible hypothesis concerning the Spark Close Phenomenon needs to take account of the “echoes” which reached absent residents of the Close – even those who were miles away at the time.

The most distant of these “echoes” seems to have reached as far as Loughborough in Leicestershire, over fifty miles away. It was there that Mr. Simon Adler-Reeves, grandson of Miss Rosa Adler, childhood resident of Spark Close and long-time friend of the Comb family, was trying and failing to write his Ph.D thesis on ‘The Portrayal of Symphonic Music in Second World War Fiction.’ At around 2.45 p.m., Simon put down the pen with which he’d not been writing, thinking he could hear white noise coming from the stereo on the other side of the room. He got up from his desk, and stepped over to the stereo. It was switched off at the socket. But he still thought he could hear something: “So I leant over one of the speakers,” Simon said, “and put my head against it. It was then that I felt this strange vibration – distant, like listening to an unborn child’s heartbeat. I can’t tell you if it was really a heartbeat, or music I was hearing; but I can tell you that, for a few minutes afterwards, I felt happy for the first time in months. Even hours later, I was feeling okay, so I decided to pick up the phone and ring my grandma – something I hadn’t done for a long time.

“That was when I found out about our neighbours’ daughter – about Melissa. I’d known her, off and on, since she was born – and I’d known the Comb family all my life. Because my parents’d been broke, we’d lived on Spark Close with my grandma when I was a kid; and then, when we moved away, I used to visit my grandma all the time and stay with her when my parents were having one of their many splittings-up. And the Combs were the one family on the Close I got to know properly – Melissa, her half-sister Serena, who I played with as a kid, Mel’s mum Lizzie, and even their dad, well, a bit. So both my grandma and myself, we were very upset at the news. My grandma, she was distraught and confused when she told me. All she said between sobs was: ‘How strange is that, you ringing now? As if you knew.’ I said it was pure coincidence. Obviously, I didn’t mention the distant noises on the stereo, or the feeling of happiness. It seemed irrelevant. It wasn’t till twenty-four hours later, when I arrived back in Stoke-on-Trent, that I realised lots of other people on Spark Close had experienced much more intense versions of what I’d heard and felt.”

In all, an estimated forty-five people with connections to Spark Close have been traced who experienced some version of the Phenomenon – who, that is, reported some kind of aural disturbance on the afternoon of the 9th June 1999. There may well be more, who have never come forward.

There were also witnesses who noticed that something out of the ordinary was happening, but who were not directly involved in the Phenomenon itself. Significantly, these passers-by saw what was going on in the Close, but were unaffected by the aural hallucination. One such passer-by was a Mrs. Rebecca Ingram, who was the second person to call the emergency services: “You see, I was on my way back from a meeting with our vicar, and had a new mobile phone with me. I need one, now I’m Neighbourhood Watch co-ordinator for Clermont Avenue. And thank goodness I had one that afternoon. They’d all gone doolally on Spark Close – wandering about, staring into space and . . . hugging each other. At first, I thought it was some jamboree, or an event for Mr. Runtill’s ‘church,’ or some anniversary I’d forgotten about. But I knew no-one had obtained Council clearance to shut the road. So next I thought: gas leak, or that incinerator down the road. Anyhow, the point was I knew something was wrong, and it was high time to call the authorities – the police and ambulance and fire-persons. So I did. It seems someone or other had phoned before me, but you can never be too careful, can you? As Neighbourhood Watch Chairperson, it’s my job to be vigilant, and call 999at every possible opportunity.”

Mrs. Ingram’s 999 call was received at 2.50 p.m. By this time, a police car and ambulance were already on their way, alerted by Miss Rosa Adler’s slightly earlier call. The hysteria of that earlier call concerned the call-handler enough for her to alert both police and medical team: “I thought it might be some schizo-pensioner rampaging on the loose,” she said later, “so it was definitely a high priority as far as I was concerned.”

But no-one was rampaging in Spark Close – quite the opposite. Once outdoors, the neighbours started to mingle and chat about their shared musical experiences.

This was about 2.55 p.m., by which point the music in most people’s heads had swelled towards a final cadence, and was ebbing away. In general, the music’s dying away ushered in an almost-euphoric sense of well-being: “I felt great,” said Mr. Frank Hutchinson. “The sun was shining, Ms. Kirsten was smiling at me – or at least in my general direction – and by now even my grandma wasn’t telling me not to smile back.” “It was the music that made us all happy,” said Mr. Paul Higgins. “Those last echoes in my head, I can’t describe them, but they felt kinda like throbs of happiness. Like you got when you were young in the seaside in Southport, and you were building sandcastles and digging holes as big as graves, and, y’ know, getting on with everyone under the sun.” Similarly, Lelly Lawson from Number 3 commented: “God, it was great – weird-great. I hate that kind of yawn-ful classical crap most of the time, the crap she –” (presumably referring to Serena Comb from Number 4) “– tries to play from ’cross the road, plinky-plonky on her piano. But when this classical crap in my head had finished, I almost wanted to say ‘come back.’ And afterwards, everything felt kind of good, and sort-of-like-I-kind-of . . . liked the people round me. I mean, I’ve always liked that Machin woman from up the street. She’s cool – got great tits, and isn’t afraid to show them off in that Geri Halliwell bikini of hers. Doesn’t give a shit about what other people think. But it wasn’t just her this time. This time, it was sort-of-like I felt everyone was great – just for a bit, you know. So I went over and started chatting with them Runtills. Can’t stand them normally, bunch of happy-clappy shites.”

Lelly mingled with the Runtills, Mr. Rajesh Parmar chit-chatted with the Shelley sisters, and then started twirling round the wheelchair-bound elder sister in an ecstatic waltz; Mr. Paul Higgins wandered between groups of people, sharing his beef and onion crisps; Mrs. Hayley Hutchinson comforted Miss Rosa Adler, who was still very upset; and Ralph the Cat purred so loudly, he could be heard twenty yards away. Mr. Raymond Runtill, fifty-year-old lay-preacher and nightclub doorman from Number 2, Spark Close, commented that: “It was like Pentecost in the Close, all of us inspired by tongues of fire and chatting with each other – however different we are. After years of just passing one another in the street, the Spirit had descended on us all. I shook everyone’s hand, as if Spark Close was my church, and it was time to say ‘the Peace of the Lord be always with you.’ But I didn’t go around saying that, not this time. Don’t know why. Instead, I just smiled at everyone, and everyone smiled at me, and we chatted about the music and the sunshine and anything else.”