0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Metaphorosis Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

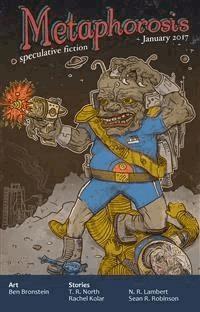

Beautifully written speculative fiction from Metaphorosis magazine. All the stories from the month, plus author biographies, interviews, and story origins. Table of Contents Snow Queen – T. R. North Business as Usual – N. R. Lambert Be Prepared to Shoot the Nanny – Rachel Kolar The Snow Queen’s Daughter – Sean R. Robinson Cover art by Ben Bronstein.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Metaphorosis

January 2017

edited by B. Morris Allen

ISSN: 2573-136X (online)ISBN: 978-1-64076-080-6 (e-book)

Metaphorosis

Neskowin

Table of Contents

Metaphorosis

January 2017

Snow Queen

T. R. North

Business As Usual

N. R. Lambert

Be Prepared to Shoot the Nanny

Rachel Kolar

The Snow Queen’s Daughter

Sean R. Robinson

Metaphorosis Publishing

Copyright

Landmarks

Title Page

Table of Contents

Body Matter

January 2017

Snow Queen — T. R. NorthBusiness as Usual — N. R. LambertBe Prepared to Shoot the Nanny — Rachel KolarThe Snow Queen’s Daughter — Sean R. Robinson

Snow Queen

T. R. North

“Do you remember the first time we met?” she asked, her voice thick and opium-drowsy, the slight thaw of early spring making her as lazy as the white-hot sun of high summer makes the old cows in their pastures.

I did, but she didn’t, and I stopped my teeth with an embroidery thread instead of telling her. She watched me with those ice-pale eyes as I clipped the thread, a gold-scarlet against my lips, hardly an accidental choice after all this time, and put my needlework away to come crouch by her divan.

She’d been in her sleigh, her half-dozen white reindeer snorting and stamping proudly in their traces, and everyone in town had turned out to see her. I’d been all of fourteen, barely noticeable in the throng with my secondhand coat and my dishwater hair and my cheeks that refused to pink no matter how hard I pinched them. I could hardly be offended that she didn’t remember.

“You were walking through the paddocks, stunning songbirds,” I lied. “You looked so lovely against the green.”

I took her hand, and she pressed my wrist gently against her cold throat so she could feel my pulse beat against her skin like a bird’s heart.

She smiled at the memory, her lips sliding up over her sharp icicle teeth, and I turned my hand so my fingertips rested just below her ear. She sighed like ice cracking on a pond.

She’d stopped the sleigh in the town square with the barest wave of her hand, the driver as awake to her whims as a flock of starlings are to a predator’s gaze. She’d leaned forward, gossamer cape shifting over the blue-tinted silk of her bodice. She’d summoned a boy I loved hopelessly and from afar, and he’d gotten into the sleigh with her like one mesmerized. He had been, of course. The weight of her regard is terrible, if a person isn’t prepared for it.

“I didn’t think you’d be out so late in the afternoon,” I continued, resting my cheek against her gown and tracing the hen-tracks of silver shot through the cloth with my free hand. “I didn’t think you’d see me.”

I’d been heartbroken when she started the sleigh again, taking him away from me, away from the village. I’d been unstrung and stupid with grief when I went to the wisewoman, the old woman who napped by the fireside at the inn, the woman I asked how to win him back, that boy who’d never been more than passing kind to me, that boy who couldn’t recall my name quite right. She’d patted my cheek and smiled kindly and said, “You don’t.”

“I had my brushes,” I said, “and I was painting your peacock’s feathers, because I felt sorry for him.”

I’d felt sorry for myself, too, when I’d walked all that way for nothing. The wisewoman had warned me, when she finally gave in and told me how to get to the ice palace, that I would not finish the journey the same as I’d started. “And, succeed or fail, if you come home again, you’ll be a different person even from that.”

It had been difficult to get here, and dangerous. It had taken five years and a day, and a great deal of cleverness. And when I found the boy, he didn’t want to leave, and he didn’t know me, and he wasn’t handsome anymore, with all the fire drained out of his cheeks and all the strength gone from his limbs. He’d been like a fish, pale and cold and listless, and about as eager to escape the palace as a fish was to leave its lake.

I couldn’t even blame him, not entirely, for not recognizing me. I caught a glimpse of myself in a looking glass as I crept out through the servants’ entrance, and I wouldn’t have known my reflection except for the gray hood, my gray hood, pulled low over my much-changed face.

My hair had been burned black when I stood in a fallow field and asked the sun which way to go, when I’d come to a place with no signposts or shadows. My face was hollow as the moon I’d followed up a mountain made of glass, her waning light the only road. My eyes were gold as the hairs I’d plucked from the devil’s own beard, while he slept and I whispered riddles in his ear. More damningly, the girl who’d spoken to the sun and chased the moon and tricked the devil hadn’t been able to remember the boy’s name, not quite. Hadn’t cared, either.