9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

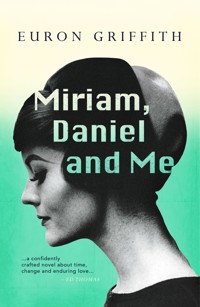

When Miriam fell in love with Padraig life seemed simple. But soon she discovered that love is a treacherous business. Everything changed when she met Daniel. She was taken down an unexpected path which would dictate and dominate the rest of her life. Spanning three generations of a North Wales family in a Welsh-speaking community, Miriam, Daniel and Me is an absorbing and compelling story of family discord, political turmoil, poetry, jealousy…and football. "...a confidently crafted novel about time, change and enduring love...and the seemingly random decisions that are made and borne by the generations who follow..." – Ed Thomas "This is an endearing and thoughtful novel about how everything can change around you, but love can remain…" ¬– Ceri's Little Blog "Wales is portrayed beautifully…A lovely, quick read - highly enjoyable!" – @youcantbeatagoodbook "Miriam, Daniel and Me showcases the ambitions, heartbreaks, and turmoil of the Meredith Family…the author highlights how unpredictable life is, but no matter which way it takes you, there's always hope for a better future. I loved the main characters, and my heart went out to Miriam. The story ends in a bittersweet manner that had me in tears." – Rajiv's Reviews "It oozes with colourful imagery and prose that will keep you turning the pages. A rich, family saga that…I really enjoyed." – Books 'n' Banter

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

MIRIAM, DANIELAND ME

EURON GRIFFITH

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd,

57 Nolton Street, Bridgend, Wales, CF31 3AE

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooksTwitter: @SerenBooks

© Euron Griffith, 2020

The rights of the above mentioned to be identified asthe author of this work have been asserted in accordancewith the Copyright, Design and Patents Act.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organisations, and eventsportrayed in this novel are either products of the author's imagination orare used ficticiously.

ISBN: 9781781725733

Ebook: 9781781725740

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise withoutthe prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistanceof the Welsh Books Council.

Cover photograph:Model with felt hat by Marka, Alamy.

Printed by Severn, Gloucester

Our lives are merely trees of possibilities

– Marc Bolan

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty One

Twenty Two

Twenty Three

Twenty Four

Twenty Five

Twenty Six

Twenty Seven

Twenty Eight

Twenty Nine

Thirty

Thirty One

Thirty Two

Thirty Three

Thirty Four

Thirty Five

Thirty Six

Thirty Seven

Thirty Eight

Thirty Nine

Forty

Forty One

Forty Two

Forty Three

Forty Four

Forty Five

Forty Six

Forty Seven

Forty Eight

Forty Nine

Fifty

Fifty One

Fifty Two

Fifty Three

Fifty Four

Fifty Five

Fifty Six

Fifty Seven

Fifty Eight

Fifty Nine

Sixty

Sixty One

Sixty Two

Acknowledgements

Author Note

ONE

God lived with us in Llys Meifor. Nain had told me. Wrapped in black shawls she was a giant spider in the corner of the room railing at whatever came on the television that was in any way fun or betraying the slightest hint of liberation.

Which of course meant everything I loved.

The Monkees and Thunderbirds mainly. Nain said that they were all going to Hell. She would declaim that All The Sinners Would Burn Forever In Flames The Size Of Mountains. I felt a bit sad for the Spencer Davis Group and Lady Penelope as they flickered on our telly oblivious to their Ultimate Fate. But Nain knew a lot about God. She spoke to him.

“You spoke to God?”

“Of course.”

“When?”

“All the time. He’s all around.”

“He’s here now? In the larder?”

Nain smiled.

“Yes.”

I looked around the shelves at the fruits of Nain’s industry. Jars of piccalilli, marmalade, strawberry jam, mustard, pickled cabbage. Tins of Welsh cakes, scones, biscuits, apple tarts and ginger snaps. In the far corner, huge hams were tucked away and covered in muslin.

But I couldn’t see God.

“Is he big Nain?”

“Big as Snowdon.”

“So how can he fit into the larder?”

“Because he can also be as small as a mouse. And he can change shapes too. You see this jar of milk? When I pour it into this small cup it changes shape doesn’t it? It’s still milk, but it’s smaller. God is like that.”

“God is like milk?”

“In a way.”

“So can I drink him?”

“What did Dr Rees say? Can you remember?”

Dr Ffrancon-Rees, the white-haired minister at Bethel chapel was seven hundred years old. He was always talking about God. In his sing-song voice in chapel he’d said that only the Pure in Heart could hear God’s words. I had no idea if I was Pure in Heart but I did try to be good. I always helped my Mum with her clothes pegs when she was putting up the washing. I brushed my teeth three times a day. I even ate broccoli, swallowing quickly before the taste kicked in. The way I saw it, if God really was everywhere then he would have spotted how good I was and made a note of it. Maybe I was Pure in Heart too. Maybe he would talk to me.

“Is God out in the garden, Nain?”

“I told you, he’s everywhere. He’s all around.”

So I went to find him.

I quickly realised that God was good at Hide and Seek. Of course, if Nain was right then God had the advantage of being able to change his size and shape and also to become invisible when it suited him so that was no surprise. I would have called it cheating but I didn’t want to upset God so I kept it to myself. I looked behind the rose bushes, avoiding the thorns, beneath the window of my Dad’s study where he wrote all his poetry. Seeing me, he smiled so I decided that he must have been in a good mood. I went in.

“I’m looking for God.”

Dad took off his glasses, placed them by the side of his typewriter and smiled.

“Nain said he was everywhere.”

“She told me that too when I was your age.”

“And did you find him?”

“No.”

“He’s hiding.”

“Maybe.”

“But why? All I want to do is talk to him for a bit.”

“God is strange.”

He ruffled my hair, put the glasses back on his nose and turned back to his typewriter. I knew this meant our chat was at an end.

I went out into the garden again and sat on the wall looking out into the fields. What if God was a cow? If he could change his shape why not become a cow? It was the perfect disguise. Who would suspect that one of the black and white Friesians in Mr Pierce’s field was actually God? He could be there all day just munching the grass and mooing and pooing and no one would bother him. I stared at them for a bit but none of them looked very smart. Besides, I was scared of cows. Everyone said they were harmless but as soon as I got close they started ganging up and lowering their heads as if they were going to charge. I decided that if God really was disguising himself as a cow I would wait until he became something else. A cat maybe. Something that would jump on my lap and start purring.

But God had moved on. He was somewhere far more exciting. And I couldn’t blame him.

Nothing ever happened in Bethel. No one interesting or new ever came to visit. There were never any strangers. Everyone knew each other by name. And everyone spoke Welsh.

Illya Kuryakin never spoke Welsh. Neither did Peter Tork, Davy Jones, Mickey Dolenz or Mike Nesmith. In a world where all the important and cool stuff was happening in English I began to question not only God but my entire universe. Dad had told me that Welsh was the most beautiful language in the world and that everyone in England was jealous of us and that was the reason they wanted to destroy it. But no one important spoke it. That was the trouble. If it was that beautiful why didn’t the Monkees use it? The only Welsh I heard on TV was some people singing hymns on a Sunday evening. There was a bigger world out there. I’d seen it on television. So I asked my Mum.

“Where does Illya Kuryakin live?”

“America.”

“Where’s that?”

“Across the sea.”

“Like Ireland?”

“Much further.”

“Can we go?”

“It’s too expensive. We would have to fly. And we’d need passports.”

“Do the Monkees live in America too?”

“Yes.”

“Do you think they’ll ever come to Wales?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Why not?”

“Why should they?”

The truth struck me like a saucepan.

We didn’t matter.

TWO

Miriam cried in her bedroom whilst, downstairs Alwyn – his customary drunkeness infused with Righteous Fury – yelled threats of disownment and violence. Eluned wailed, not knowing what to do or what to think – her life suddenly a shattered vase. Having had her only daughter threaten to become a Catholic and move to Ireland only a month or so earlier had been a terrifying prospect but now, seeing her pregnant out of wedlock to a man they hadn’t even met was even worse. Everyone in Cysegr chapel knew about it and, on Sundays, heads were bowed in embarrassment and shame as Alwyn, Eluned and Miriam walked past in their finery, clutching their hymn books and taking their usual pew. Miriam was told by Eluned that she would have to write to Pádraig and tell him what had happened. It was her duty to tell him. As a good Catholic he might even recognise her confession and offer forgiveness although Miriam knew that forgiveness was as remote and as meaningless as Mars. Somewhere in Dublin he was waiting for her letter and looking forward to hearing about the tiny and inconsequential events of her week with Leah at the shoe shop. Her moans about the stupid customers and the monstrous Mr Oliver! It was the thing he looked forward to now that the letters had started arriving again. He had been worried for a while. He had wondered if there had been someone else. But he’d been wrong to doubt her love. The row of hastily crossed kisses at the end of her letters were all the proof he needed. And the hint of perfume too. In one letter there had even been a pressed wild violet from one of the Pantglyn fields. He’d written back telling her about the cottage they would buy one day on the cliffs. They would have a dog. And enough straw bobbies to fill a whole house just like he’d promised. A small cottage maybe. Although definitely not a mansion.

None of it mattered now. None of it would happen. There would be no more letters.

And it was her own stupid fault.

Twenty-two year old Pádraig came from Dublin and was very good with his hands. There was nothing he couldn’t fix. Fridges, phones, crooked bookshelves, cars – everything was a challenge and whatever Alwyn or Eluned presented him with would be carefully assessed and inspected before being returned to them in as good a condition, if not better, than its original state. Watching young Pádraig fit a plug onto the new food mixer was like watching a vet coolly perform a life-saving procedure on some tiny animal, tucking in the wires like troublesome intestines whilst occasionally puffing the ginger fringe from his face.

“There you go Mrs Walters, that should see you right.”

Alwyn would have messed it up. Fiddled for ages. Complained about the screwdriver. Scrambled around the toolbox noisily spitting out words which would never be heard within fifty yards of Cysegr chapel. There were times when Alwyn would have loved to smash his young lodger in the face. But everyone in Pantglyn adored Pádraig. When he smiled it really did feel as if the chilly Caernarfonshire wind had stopped for a few seconds and as if the place had suddenly got warmer. When the words tumbled out of his mouth it sounded like a pleasing arpeggio on a harp. He’d only been there for a couple of months, lodging in Carneddi – the Walters’ terraced cottage – whilst he worked as an apprentice electrician in a small firm just outside Caernarfon, but in that time Pádraig had made the village of Pantglyn a nicer place. No one had an unkind word. The men in the pub loved him. Even the local minister loved him.

But nobody loved him more than Miriam.

In the beginning she had been quite antagonistic. Why did they need a lodger? No one else in Pantglyn had one. And she had always liked having a spare room next to her own. It was her special place. Somewhere to run to when she wanted the world to go away or when Alwyn’s drinking had gone too far and he was throwing things around downstairs and shouting at Eluned. Now that sanctuary was gone and, worse, she had to be on her best behaviour in the morning at the breakfast table. All because of a stupid Irishman.

Love came as a shock. As unexpected as a wolf in a parlour. Naturally, as a young girl of eighteen, she’d read about love in her magazines and she’d seen it on the screen of the Majestic cinema in Caernarfon but real love was different. It was something she felt. Like stomach ache or dizziness. No magazine or film had told her that. It seeped into every part of her body and every part of her day. Even the act of walking to the bus stop every morning was something she now had to think about because that mechanical and previously automatic action of placing one foot in front of another whilst swinging her handbag now became an object of pure concentration. It reminded her of when Alwyn was drunk and when he tried to walk in a straight line to convince Eluned that he was sober. Miriam worried that, at any moment, if she wasn’t careful, she would crash into a wall and draw attention to herself or, equally possible, she might just float up from the pavement entirely, drifting like a daft balloon up through the clouds – Pantglyn becoming insignificant matchboxes beneath her heels.

At night she would listen to the sounds from her old sanctuary. Now it was Pádraig’s room and she heard the creaks from his bed. Sometimes he would hum a little song to himself, no words, just a snatch of a melody which, to Miriam, sounded as lovely as a flute. Even his snoring sounded musical. Love was turning the world into some weird and peculiar opera she couldn’t quite follow.

“Have you ever been to the Fair City?”

Alwyn and Eluned had gone out for the evening. It was a warm Spring evening and Miriam and Pádraig were alone in the back garden.

“Where’s the Fair City?”

Pádraig chuckled gently.

“That’s what they call Dublin. It’s the most beautiful city in the world. You should come with me one day. We could buy a cottage by a cliff overlooking the Irish Sea and I could make you a straw bobby every morning to keep you company while I go to work.”

“What’s a straw bobby?”

Pádraig ripped out a bunch of grass.

“Close your eyes.”

She heard him twisting and pulling the grass until it squeaked.

Then, after twenty seconds had passed, she heard his voice again.

“Okay, you can open them now.”

He placed a beautifully-crafted doll, a little grass man, in her hand.

“I can make enough to fill a house,” said Pádraig. He laughed. “A small cottage maybe. Although definitely not a mansion!”

Miriam laughed back as she stroked her straw bobby. But then she became serious again.

“Do you have to go?”

“It’s only for a month. Maybe even less. The doctor said she was on the mend so you never know.”

“I don’t want you to go.”

Pádraig watched her cry. He offered his hand and she took it as if it contained all the treasure in the world.

She got up carefully, took her big bag down from the top of the wardrobe and filled it with clothes, not really caring what she packed – stockings, blouses, skirts – all stuffed in, as much as she could manage. Shoes were dropped into a plastic bag. Make-up tucked into her coat pocket. Was Dublin going to be cold? Did she have enough money? She’d saved a little. She unscrewed the belly from Puw, her porcelain pig, and the coins tumbled out of his guts. Silver was judiciously separated from copper. But there was far too much copper. There was five pounds in Eluned’s purse. She would borrow it. Leave a note. When she got a proper job out in Dublin she would repay the amount with interest. The suitcase wasn’t too heavy. She took it down the stairs and listened to the sound of Alwyn’s snoring. Once downstairs she took the five pounds from Eluned’s purse and took one last look at the kitchen. Pádraig had left ten minutes earlier. The bus was due in five. She opened the door and closed it behind her as quietly as she could.

“What are you doing girl? Look at you, all dressed up!”

“I’m coming with you.”

“What?”

She had wanted him to be happier. Now she suddenly felt the cold. Pádraig led her away from the bus stop. There was only one other person there, an austere looking woman in black.

“You have to stay,” said Pádraig, his voice low and firm. His hands clasping her shoulders. “You can’t come.”

“But you said I should go. Go to the Fair City!”

“One day yes. But now now! Where will you stay?”

“I don’t know! I thought... maybe...”

Pádraig sighed as he saw the tears.

“Here. Take this.”

The handkerchief smelled of him. She dabbed her cheeks. The bus appeared in the distance and the austere woman in black picked up her bags in preparation. Miriam knew it was hopeless.

“Go back,” said Pádraig. He squeezed both her arms and smiled sadly. “Really. I’ll be back before you know it and, anyway, I’ll write.”

He kissed her on her cheek. Then he picked up his suitcase and stepped onto the bus. The doors closed behind him and the driver pulled off before Pádraig had even had a chance to sit down.

THREE

She fell backwards onto her handbag and she could feel and hear the plastic crunch of things breaking and snapping. Her makeup and lipstick. Her mirror. The driver shot out of the car and started to shout. There was a cigarette glued to the corner of his mouth

“What the hell were you thinking?”

Miriam sat up. The tarmac was rough against her palms. The young driver flicked away his fag and helped her up.

“I’m so sorry. I wasn’t looking.”

“Thank God one of us was!”

A small crowd had gathered to see if there was any blood or carnage and now they drifted away slowly, almost disappointed that the young girl who had been knocked down seemed to be okay apart from a dirty coat and a shattered bag.

“I hope I didn’t damage your car.”

The young man laughed.

“I was barely out of first gear. And anyway, I can’t see how something as skinny as you could damage a Ford Popular.”

She half smiled and walked away, trying hard to bury her face in her coat. Some of the people in the crowd on Caernarfon’s main square – the Maes – must have recognised her as the young assistant from Mr Oliver’s shoe shop. How she wished she lived in a big city where she could melt into the crowds and be anonymous whenever she felt like it. Somewhere like London or Liverpool. Or Dublin.

As she walked, patting down her coat and fluffing up her hair, she wondered what Pádraig was doing right at that moment. Had he been around he would have rowed with that man with the black Ford Popular. He might even have punched him on the nose. But then if Pádraig had been there she wouldn’t have been run over in the first place. He was the reason why she’d stepped out without looking. She was thinking of him. Missing him. Wondering if she’d been forgotten and if there was another girl on the scene. Some Irish coleen. That’s what he called the Irish girls back home. ‘Coleens’. She’d always found it such a lovely word in the past but now it sounded ominous and threatening – like an Irish word for ‘witch’.

“You’re late.”

“I know Mr Oliver. I’m sorry.”

“Second time this week.”

“It won’t happen again.”

He grunted and coiled the silver watch-chain into his waistcoat.

“Last warning. Do you understand?”

Mr Oliver smiled politely at Mrs Bennett and Mrs Bennett smiled back. Leah raised her eyebrows at Miriam but then, feeling the glare of Mr Oliver, she took out a shoe from a box and placed it in front of the customer.

“Try this one Mrs Bennett.”

“Remember to lock up Leah.”

“I will Mr Oliver.”

“Dental appointment,” said Mr Oliver, feeling that he owed his customer an explanation. “Two fillings.”

“Oh dear,” said Mrs Bennett.

“Can’t be helped. Right. I’ll bid you good day.” He doffed his bowler hat in Mrs Bennett’s direction. “See you tomorrow girls. Bright and early.”

“Yes Mr Oliver.”

Mr Oliver yanked down his cuffs, tightened his cravat and opened the door. The bell tinkled, there was a fleeting rush of cold air. And then he was gone.

Mrs Bennett shivered.

“Bit of a tyrant isn’t he?” she said. “Gives me the creeps he does. I don’t know how you can stand it. I see his wife in Woolworths sometimes. Meek as a mouse she is.” She lowered her voice. “They say he beats her.”

“Not too tight are they Mrs Bennett?” asked Leah.

“No love.”

“Why don’t you have a little walk round to check.”

Mrs Bennett teetered across the carpet as if she was on a tightrope.

“I’ll take them.”

“I’ll get the box.”

At the end of the afternoon Leah locked up the shop as instructed. She even rattled the doors to double-check that they were secure.

“There,” she said, dropping the keys in her handbag. “Even Harry Houdini couldn’t get in now!”

FOUR

“I mustn’t stay long,” said Miriam. “My Dad would give me a real talking to if he knew I was coming in to The Britannia straight after work.”

“You’re with me,” said Leah, teasingly. “I’ll keep you on the straight and narrow. Mind you,” she glanced over Miriam’s shoulder and leant in, lowering her voice. “There’s a man at the next table who keeps looking at you.”

“At me?”

Leah whipped out her arm to stop Miriam from turning round.

“He’s coming over.”

“Oh God!”

“Just look calm. Sip your gin. Pretend you don’t care.”

“Mind if I join you?”

Leah looked up and flashed the stranger her best smile.

“Please do.”

The stranger placed his pint on the table and sat down. His eyes were on Miriam all the time.

“No hard feelings I hope?”

“No,” said Miriam, reddening. “Of course not.”

Leah leant forward.

“What’s going on?”

“We had a bit of a mishap,” said the stranger. “She ran out into the road this lunchtime and I knocked her down.”

“What?”

“Nothing,” said Miriam, embarrassed and not wanting a fuss. “Honestly Leah. It was my fault.”

“Daniel,” said the stranger, extending his hand to Leah. “Pleased to meet you.”

Leah looked at the proferred hand with distaste. But, after a quick glance at Miriam, she took it.

“Let me get you girls another,” said Daniel. “Same again?”

Pádraig’s letters landed heavily on the porch mat twice a week. Sometimes there were photographs of Dublin inside, or pressed flowers plucked from Iveagh gardens – their delicate petals soft and almost translucent. His letters told her everything he’d been up to. His mother was on the mend and should be on her feet soon. Then he would come back to Wales. He told her not to worry.

But then there was another letter. The handwriting was unfamiliar and yet the postmark was local. Caernarfon. Eluned had propped it up against the marmalade jar one morning and the clear invitation was for Miriam to open it over the breakfast table but she just looked at it and tucked it in her pocket.

“It’s not from Ireland,” said Alwyn, winking mischievously at Eluned.

Miriam stood up.

“I’m late.”

As the bus to Caernarfon rattled and rocked like a galleon, Miriam took the strange, thin letter out of her pocket and opened it. It wasn’t a proper letter at all. It was a poem. Eight lines long, it seemed to describe mountains, skies and birds. She wasn’t sure if she understood it. The Welsh it used was so dense, not the normal Welsh everyone spoke in Caernarfon and Pantglyn – this was more like the type of Welsh she’d had to learn in those boring old books at school. She turned the paper round just in case there had been anything written on the back but there wasn’t. Strangely disappointed, she slipped the poem back in the envelope.

That afternoon Daniel came into the shop wearing a smart blue suit and with his thick black hair greased back in a shiny pile. It was Leah’s afternoon off and Miriam was on her own.

“What are you doing here?”

“I need shoes.”

He raised his foot.

“They seem fine to me.”

“They pinch.”

Mr Oliver cleared his throat in the back office.

“Sit down.”

Daniel smiled and did as he was told. He took off his left shoe.

“Size ten,” he said. “Preferably black. Nothing too fancy or expensive. And something I can wear to chapel.”

He wasn’t interested in new shoes. She wasn’t born yesterday. She picked up a black leather brogue.

“How about something like this?”

Daniel didn’t even look at it.

“Perfect.”

“Try it on.”

“Can you help?”

Miriam knelt down and gently guided his left foot into the brogue.

“You’ve got soft hands.”

“Not too tight?”

“I’ll take them.”

“I’ll fetch the box.”

“Wait. Have you heard of T.J. Watcyn?”

“Who?”

“The great Bard. He’s got one of those big old Victorian houses up in Twthill. He wrote a beautiful poem about the Spring and how it encourages lovers.”

“I don’t really read a lot of poetry. Let me get the box – ”

“Hang on.”

Daniel took her arm.

“He’s giving a talk and a reading. Over at the Wilson Club on Saturday. I was wondering if you’d like to come.”

“Me?”

“Why not?”

“But the Wilson Club is full of stuffy old men! Why would I want to go there?”

FIVE

She was the only woman in the room. A semi-circle of chairs curled around a lectern. Daniel leant over.

“Strange first date.”

“It’s not a date.”

Guilt clenched up like a tiny fist inside her as she thought again of the two unanswered letters from Ireland tucked into the drawer of her dressing table at home. She still loved him. She knew that. They were virtually engaged after all. She was still going to go to Dublin, become a Catholic and have lots and lots of children. Pádraig would come back soon and take him with her as his wife next time he went.

A sudden burst of enthusiastic applause signalled the appearance of an old man in a brown jacket who stepped up to the lectern and placed a big black book in front of him like a minister about to unleash a sermon. His hair was long, much longer than any man’s hair Miriam had ever seen and it was as white as woven cobwebs in sunlight. A young man placed a glass of whisky on the lectern next to the big black book and the old Bard looked surprised, but happy to see it. He raised it to the audience, took a sip and cleared his throat. The room became silent. Expectant. Daniel took her hand. Miriam thought of pulling it away but she didn’t.

During a gap between the third or fourth poem – none of which Miriam had felt she understood – whilst T.J. Watcyn sipped his second whiskey, Daniel leant across to Miriam.

“He runs weekly classes here every Wednesday night,” he whispered. “I’m thinking of going along. Introduce myself. Maybe take some of my poems for him to see.”

“You should.”

“He has his cronies though.”

He nodded in the direction of a table near the lectern where three serious-looking young men were sitting down and taking notes. They were the ones who had bought T.J. Watcyn the whiskies.

“They’re so much more advanced than me,” said Daniel. “Older too. One of them has a beard!”

“You have to start somewhere,” said Miriam. “And you can always grow a beard by Wednesday if you work at it.”

Pádraig described a trip he’d taken to a bird sanctuary near the coast at Kilcoole. He’d even made some drawings in coloured pencils. One day, he wrote, he would love to live in a cottage by the sea. Preferably high up on a cliff. They could walk the pathways with their children and tell them all kinds of stories about Kings and Queens and mythical beasts. If he was concerned about her lack of replies he didn’t mention it.

“‘Dear Pádraig,’” she wrote one night. “‘Sorry I’ve been so slow in writing back. It’s just that work has been so busy and Mr Oliver has been a right pain in the neck!’”

She had never written a lie before.

“‘I wish I could find another job. I really do. Maybe when I come over to Dublin I can find something nice. In an office maybe. Typing or keeping things tidy.’”

But Dublin had slipped away. Further than China.

“‘The bird sanctuary sounds nice. And such lovely drawings. How I wish I could draw. But I was always useless. All I could dowere little stick men! The cottage by the sea sounds so lovely. Let’s hope we can do that one day.’”