9,95 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Glagoslav Publications B.V. (N)

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Edited, translated, and introduced by Anatoly Kudryavitsky, this bilingual anthology presents Russian short poems of the last half-century. It showcases thirty poets from Russia, and displays a variety of works by authors who all come from different backgrounds.

Some of them are well-known not only locally but also internationally due to festival appearances and translations into European languages; among them are Gennady Aigi, Gennady Alexeyev, Vladimir Aristov, Sergey Biryukov, Konstantin Kedrov, Igor Kholin, Viktor Krivulin, Vsevolod Nekrasov, Genrikh Sapgir, and Sergey Stratanovsky.

The next Russian poetic generation also features prominently in the collection. Such poets as Tatyana Grauz, Dmitri Grigoriev, Alexander Makarov-Krotkov, Yuri Milorava, Asya Shneiderman and Alina Vitukhnovskaya are the ones Russians like to read today.

This anthology shows Russia looking back at itself, and reveals the post-World-War Russian reality from the perspective of some of the best Russian creative minds. Here we find a poetry of dissent and of quiet observation, of fierce emotions, and of deep inner thoughts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 78

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

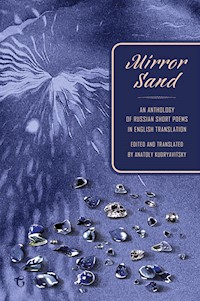

MIRROR SAND

An Anthology of Russian Short Poems in English Translation

Translated byAnatoly Kudryavitsky

MIRROR SAND

An Anthology of Russian Short Poems in English Translation

(English only edition)

Edited, translated, and introduced by Anatoly Kudryavitsky, this anthology presents Russian short poems of the last half-century. It showcases thirty poets from Russia, and displays a variety of works by authors who all come from different backgrounds. Some of them are well-known not only locally but also internationally due to festival appearances and translations into European languages; among them are Gennady Aigi, Gennady Alexeyev, Vladimir Aristov, Sergey Biryukov, Konstantin Kedrov, Igor Kholin, Viktor Krivulin, Vsevolod Nekrasov, Genrikh Sapgir, and Sergey Stratanovsky. The next Russian poetic generation also features prominently in the collection. Such poets as Tatyana Grauz, Dmitri Grigoriev, Alexander Makarov-Krotkov, Yuri Milorava, Asya Shneiderman and Alina Vitukhnovskaya are the ones Russians like to read today. This anthology shows Russia looking back at itself, and reveals the post-World-War Russian reality from the perspective of some of the best Russian creative minds. Here we find a poetry of dissent and of quiet observation, of fierce emotions, and of deep inner thoughts.

Introduction copyright © Anatoly Kudryavitsky, 2018

English translations © Anatoly Kudryavitsky, 2006, 2018

Original Russian-language poems © their individual authors, 2018

This collection copyright © Glagoslav Publications, 2018

Front cover image © Jassemine Darouiech, 2018

Cover and layout design by Max Mendor

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN: 978-1-91141-474-2 (Ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Gennady Aigi

The Silence of Snow

Hush

The Rain

Snowstorm in My Window

Our Way

Ivan Akhmetiev

The Challenge

A Pause

Writing

Waiting

Observation

Margarita Al

Desire

Wings

The Poet

The Beast Hasn’t Been Born Yet – but It Already is a Beast

A Porcelain Morning

Maria Alekhina

Pushkin Square

The Room

Prescience

Time

Simple Life

Gennady Alexeyev

Every Morning

My Funeral

Flowers

A Poem About the Disadvantages of Being Human

What I Want

Vladimir Aristov

From “Accidentally Met in Moscow”

The Surface of the Chinese Mirror

The Dragon

For A.U.

Infernal Repetitions

Sergey Biryukov

Everything Changes

Who’s Good?

Beastmen

The Treble Clef

News of Petrarch and Laura

Vladimir Burich

At Night I Looked into my Room Through the Window

Half Past Seventies

What Will Remain

Germany, 1984

On the Boulevard

Vladimir Earle

Autumn

The Barrier of Sleep

Opinions

Eurydice

Under Water

Mikhail Finerman

Touching

Yearning

Name

Winter

To Find Yourself

Ruslan Galimov

Forecast

In General, She Was Right

Agreeability

What Can Man Think About?

Today

Tatyana Grauz

Morning Dream

July’s Light

Butterfly

Soft Sun

April-Dove

Dmitry Grigoriev

Night

Words

Shades of Night

Not Rubbish

Fishermen

Elena Katsuba

Candle

Butterfly and the Rain

An Apocryphal Story

There’s Nothing Replaceable in the Dump!

The Rose Garden

Konstantin Kedrov

Hieroglyph for God

Aero Era

Keel

Reed Pipe

Wings

Igor Kholin

Cramer’s Camera

Poem for Edmund Iodkovsky

From “The War River”

Common Grave

Truths

Viktor Krivulin

Lynx

While We Invented Paradise

Books and Men

Over the Granite Factory

The End

Anatoly Kudryavitsky

Chamber Music

Bunin: Portrait with the Person Missing

Judas

The Invisible Cinema

The Shooting Down of MH17

Alexander Makarov-Krotkov

For K.

On the Quays

The Doggy

Stockholm

A Soviet Reader’s Remark on James Joyce

Arvo Mets

The Poet

Absentee

Resemblance

Penniless Man

Names

Yuri Milorava

Untitled 1

Untitled 2

Untitled 3

Untitled 4

Untitled 5

Vsevolod Nekrasov

Freedom

Untitled 1

Untitled 2

Pride

Love

Rea Nikonova

Simple

The World of Idiots

Anti-Novella

Foretaste

Russia

Genrikh Sapgir

Grove

New in Town

Business Trip

A Proverb

Sounds of Silence

Ian Satunovsky

Changing the Bulb

If They So Desire

Almost by Mistake

Writing

A Bloody Yid

Asya Shneiderman

Poetry

The Tower

The City

Poem for Lena Zhukova

Especially in this Kind of World

Mikhail Sokovnin

Fantasy

Woodsman

Samovar

A Northern Song

Untitled

Sergey Stratanovsky

In the Nabokov Hotel

A Shark as a Cabinet of Curiosities

Leviathan

The Library Tower

An Apocryphal Story

Arkady Tyurin

Inseparability

It Is Careless of You …

Time and the River

She

Garden

Alina Vitukhnovskaya

By Touch

Your Chaos

Zero

Pavlov’s Dog

Eva Browning

About the translator

Thank you for purchasing this book

Glagoslav Publications Catalogue

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the editors of the following, in which a number of these translations, or versions of them, originally appeared:

Hayden’s Ferry Review, Cyphers, Das Gedicht, Poetry Ireland Review, The SHOp, Shot Glass Journal, SurVision, Public Pool, Four Centuries, World Poetry Almanac (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia), A Night in the Nabokov Hotel anthology (Dedalus Press, 2006).

Some of these poems, in English translation, were first broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of the copyright to the works by Vladimir Burich, Mikhail Finerman and Arkady Tyurin, and to obtain permissions to reproduce their works. Please do get in touch with any enquiries or any information relating to their poems or the rights holders.

Introduction

A saying has it that Russia produces more than it can consume locally. Should this refer to Russian poetry? Western readers are well acquainted with poetry written in that country over the last three centuries, from Alexander Pushkin to Anna Akhmatova, mostly through translations. Some other Russian poets, including Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Brodsky, felt at home at writing in English. This book offers an opportunity to hear a few newer voices.

As Vladimir Nabokov once put it, “Literature belongs to the department of specific words and images rather than to the department of general ideas.” Unfortunately, the general idea in Communist Russia was to encourage and publish only those writers who supported and even glorified the regime. It was Government policy, especially strict after the last world war. It is inconceivable now that any European poet could write a paean for the President of the European Council, but we have to bear in mind that in Communist Russia, even in the 1980s, this sort of poetry was a commonplace. Other poets ran the risk of being treated with suspicion by each and every literary vigilante. Should we be surprised by Marina Tsvetayeva’s line: “All the poets are Jews”?

“After Pasternak, Russian poetry sustained a pause,” the late Genrikh Sapgir used to say. It was destined to be a long pause. In fact, the generation of Russian writers that emerged in the early 60s grew up reading and studying in college Russian poetry from the 1920s. Some of them were particularly inspired by Boris Pasternak and Osip Mandelstam, others by Velimir Khlebnikov and other Russian Futurist poets. What appeared in Soviet “fat magazines” in those times were, to quote Anna Akhmatova, “rhymed editorials”, or otherwise third-rate imitations of Symbolist poetry from the late nineteenth century.

In these circumstances some Russian poets chose to refrain from publishing anything openly, while others were banned from publishing. Writing “into the table” became customary for them. Many of them explored the possibilities of so-called “open poetry”. By stripping their pieces down to a most basic expression, and outlawing most literary devices or even emotional colouring, they focused their attention on individual words, or even on fragments of those words and sound units from them. This style was later defined as minimalism. One can trace the sources of modern-day minimalist texts to Dadaist, Surrealist, Concrete and even Zen poetry, and it definitely displays parallels to the visual arts. Minimalist poets focused on bare words or phrases, sometimes rearranging them on the page so that their most basic and individual properties disclosed something unexpected about themselves.

The work of these poets wasn’t minimalist in the sense that they had little to say; quite the contrary, it captured the frustration, suppressed ambitions and hidden energy of several generations of Russian people. As Vassily Kandinsky once put it, “Even absolute silence is a loud speech.” Joseph Brodsky in one of his lectures compared Mark Strand and Charles Simic, well-established American “poets of silence”, as he called them, to “unofficial” Russian poets who had to dwell in silence, due to having no other literary space. Rea Nikonova, a poet from the South of Russia, even produced a catalogue of different kinds of silence. She knew very well what she was talking about as she first lived in Yeysk, a small Russian town on coast of the Azov Sea – and then on the other shores of exile, in Germany, until her untimely death.