Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

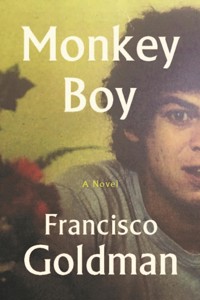

'Full of rebellious comedy and vitality... Goldman's autobiographical immersion answers the urgent cry of memory... [He] is a natural storyteller - funny, intimate, sarcastic, all-noticing.' James Wood, New Yorker Francisco Goldman's first novel since his acclaimed, nationally bestselling Say Her Name (winner of the Prix Femina étranger), Monkey Boy is a sweeping story about the impact of divided identity - whether Jewish/Catholic, white/brown, native/expat - and one misfit's quest to heal his damaged past and find love. Our narrator, Francisco Goldberg, an American writer, has been living in Mexico when, because of a threat provoked by his journalism, he flees to New York City, hoping to start afresh. His last relationship ended devastatingly five years before, and he may now finally be on the cusp of a new love with a young Mexican woman he meets in Brooklyn. But Francisco is soon beckoned back to his childhood home outside Boston by a high school girlfriend who witnessed his youthful humiliations, and to visit his Guatemalan mother, Yolanda, whose intermittent lucidity unearths forgotten pockets of the past. On this five-day trip, the spectre of Frank's recently deceased father, Bert, an immigrant from Ukraine - pathologically abusive, yet also at times infuriatingly endearing - as well as the dramatic Guatemalan woman who helped raise him, and the high school bullies who called him 'monkey boy,' all loom. Told in an intimate, irresistibly funny and passionate voice, this extraordinary portrait of family and growing up 'halfie' unearths the hidden cruelties in a predominantly white, working-class Boston suburb where Francisco came of age, and explores the pressures of living between worlds all his life. Monkey Boy is a new masterpiece of fiction from one of the most important American voices in the last forty years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 566

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MonkeyBoy

ALSO BY FRANCISCO GOLDMAN

The Interior Circuit

Say Her Name

The Art of Political Murder

The Divine Husband

The Ordinary Seaman

The Long Night of White Chickens

First published in the United States of America in 2021 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Francisco Goldman, 2021

The moral right of Francisco Goldman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 648 4

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 886 0

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Jovi and Azalea Panchita

For Binky Urban&In memory of my mother

“Why you monkey,” said a harpooner . . .—Herman Melville, Moby Dick

“And now I want you to tell me,” the woman suddenly said with a terrible force, “I want you to tell me where one could find another father like my father in all the world!”—Isaac Babel, “Crossing the River Zbrucz,”Red Cavalry

When someone goes on a trip, he has something to tell about . . .—Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller

Thursday

FIVE DAYS A WEEK and sometimes on Saturdays, too, my father used to get up at 5:45 a.m. to go to work at the Potashnik Tooth Corporation in an industrial pocket of Cambridge, a half hour or so drive from our town if you knew how to avoid the traffic. Moving around this apartment at that same predawn hour all these years later, hurriedly packing for my trip to Boston, I remember how his moving around the house always woke me before I had to get up for school: bathroom noises, heavy tread on the stairs, the garage door hauled up like a loud ripping in the house’s flimsy walls. My father kept his Oldsmobile in the driveway but always came into the house through the garage. Late school-day afternoons and evenings, I especially dreaded that garage-door sound. Unless what I heard next was my mother’s Duster coming inside, the flinching chug of her light nervous foot on the brake, it meant Bert was home and would soon be coming up the stairs. If I was listening to music on my little stereo I’d turn the volume way down or snap it off to be sure to hear his footsteps outside my door. Sometimes, if he was really angry at me over something or other, he’d burst into my room without knocking.

I remember no part of life inside the house on Wooded Hollow Road, which we moved into when I was in fifth grade, more vividly than my fear of my father. It seems now like years went by without a day when he wasn’t angry. But that must not be true, not every day; it’s not like there weren’t things in his life that didn’t bring my father joy or a kind of joy. Bringing home a new sapling or bush from Cerullo Farm and Nursery to plant in the yard on a weekend morning or winning his football bets and collecting from his bookie, joy.

But what a shitty start to the day, thinking about old Bert, feeling like his shadow is falling across the decades into my apartment as I get ready to head out the door doesn’t seem to augur too well for the trip ahead. But I’m not like my father, am I. He’d let any little frustration enrage him. Right now he’d be stomping from room to room noisily seething: God damn it to hell, where’s that goddamned Muriel Spark. Even in the most berserk moments of some pretty overwrought relationships, I’ve never even once screamed at another person the way he used to when he’d really lost it. Okay, here it is, on the sofa facing the TV, hiding underneath the Styrofoam tray last night’s beef chow fun came in, The Girls of Slender Means. I left it out to read on the train, a bit of homework before I see my mother tomorrow. The novel, according to the back cover, is set in a London boardinghouse for single young working women right after World War II, and Mamita lived in one of those, though in Boston, and in the 1950s.

Five months ago, in October, after I’d moved back to New York from Mexico City, I rented this parlor-floor apartment in a brownstone in Carroll Gardens. I still had stuff in storage from when the city had last been my home, nearly ten years ago. But I’ve only visited since, coming up to New York once a year, sometimes staying as long as a few months. I didn’t want to move back but felt forced to by a warning I received in Mexico that I probably could have ignored. But it didn’t feel that way at the time, so I fled. The warning was the result of my journalism on the murder in Guatemala of a bishop, the country’s greatest human rights leader, including the book I published less than two years ago. Maybe in some unacknowledged way I wanted to come back to New York. Thirty years ago, the first time I ever came here to live, I was also fleeing, looking for a refuge from humiliation, a new start. I don’t buy that myth of New York City as a place to come and begin your ambitious climb. Better to arrive humbled, self-embarrassed, it kind of de-hierarchizes the city, spreads it out, offering you more places to hide and also more room to move, to discover yourself in obscure corners, inside shadows and murk. In the past, not wanting to miss out on the chance for some ever-elusive apotheosis, clinging to a relationship or some romantic delusion, I wouldn’t have taken the time for all these trips home to Boston to see Mamita.

When I visit my mother tomorrow in Green Meadows, her nursing home, it will be for the fourth time since I moved back, this after a decade of sometimes seeing her only once a year. My sister, Lexi, visits a couple of times a week and speaks to her on the phone at least once a day. After all those years of living abroad when I often couldn’t remember to phone her even once a month, I do try to talk to my mother every week now. She hasn’t felt so present in my life since I left home for good at eighteen. It seems now like she’s always just a quick thought away, and I like to picture her in her room at the nursing home with her patient rabbit smile, waiting to resume our conversations. I was a little puzzled when I noticed that I’m not in any of the framed photographs on her windowsill and wondered what the reason was; really, I should just bring her a picture now. Two photos of Mamita with her own mother are displayed there, one from when she was in her midtwenties and Abuelita came to Boston to help her move into that boardinghouse and get her settled; the other is from a few years before Abuelita died, when she looked quite a bit like my mother does now, puffy around the eyes, eyelids drooping. There’s a photograph of Lexi from when she went to Guatemala during a college summer vacation: she’s standing on the rough stone steps of the famous old church in Chichicastenango, smiling zestily, surrounded by the usual kneeling Maya shamans with their smoky incense censers, lighting candles, beseeching and casting spells for their clients. Another from about a decade later shows Lexi and our parents in a familial pose, standing close together, mother and sister in flowing dresses for who knows what occasion I wasn’t at, my father in jacket and tie, but you can’t see his face because of the piece of cardboard taped over it. Only Lexi could have decided to do that, though apparently without much opposition from our mom. When I asked Mamita about it, she looked blank for a moment, then there was a flicker of recognition in her eyes and she dismissively clucked her teeth like she does and said, Ach, no se, Frankie. I wonder if the nurses and other staff laugh to themselves over that photo, some even thinking: Oh yeah, I know about husbands and fathers like that.

Usually on these visits I spend at least a couple of nights in Boston hotels and sometimes a night at a highway hotel near the nursing home, located in a town nearly at the end of a commuter train line out to the southern suburbs. If I have to live up here again, for however long it turns out to be, this seems as good a time as any, when my mother has obviously started her mental and physical decline but for the most part is still lucid enough to have good conversations and giggles with. Ay, Mamita, we make each other laugh, anyway, don’t we?

I head down the sidewalk in the cold March, just predawn dark, feeling half-awake and half-asleep, pulling a wheeled carry-on. I forgot to take the locker padlock I use at the gym out of the backpack hung over my shoulders, and the lock knocks against my back in rhythm with the fall of my boot soles on the pavement, a muffled clanking the quiet seems to amplify along with the suitcase’s clacking wheels: clackclack clink clackclack clink.

The subway ride into Manhattan doesn’t fully belong to the awoken world either. There are grim-faced, sleepy-eyed early commuters, some with heads heavily nodding down as they sit, and a few homeless men sleeping across the seats, blankets so blackened they look made of cast iron; it’s like this train is transporting exhausted spirit miners out of a supernatural mine.

I still always call it going home to Boston, though I haven’t lived in that city since I was an infant, back when my newlywed parents had an apartment somewhere on Beacon Street. But this year I didn’t go home to Boston to spend any part of the Christmas holidays with my mother and sister. In early December I flew to Buenos Aires to report a magazine article on the search for the missing and stolen children of parents disappeared in the Dirty War years and stayed until just after the New Year. Then I’d only been there a few days when I got an email from my sister saying how happy she was that we’d be able to spend Christmas together for the first time in so many years. I hadn’t told Lexi I’d be in Argentina for the holidays, though I had told our mom, but she’d probably forgotten to pass that on. Instead, I was invited for Christmas Eve dinner with one of the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo and her recently recovered grandson, the only son of her only daughter, who’d given birth while a secret prisoner of the military dictatorship twenty years before, after which she’d “disappeared” forever, most likely rolled from the bay of a plane into the South Atlantic. Her son’s identity had been confirmed by DNA testing only a few months before. For my piece, I only had to try to describe that Christmas Eve just as it was in order to transmit an appropriate sense of the sacred, of the mystical presence of the missing mother-daughter—Paulina was her name—her blessing and love in the new bond between a grandson and grandmother who until recently had been strangers. Later, I got mail from readers who were moved by that scene especially, a few who had stories of their own to share about lost or missing mothers, even of ghostly visitations during holiday family gatherings and weddings.

In her email, Lexi wrote that we could hire a caregiver and take our mother, in her wheelchair, from the nursing home to have dinner in a restaurant, or else we could even have Christmas at her house in New Bedford. “I can’t think of a better occasion for you to finally come to my house and see how I live here,” she wrote. I’ve never been to the house Lexi bought a few years ago out in that old fishing port and now mostly defunct manufacturing city. She bought it as an investment, she says, with the money she got from our parents. An old gabled New England manse-looking place, originally built supposedly for a whaling captain back in the Melville time. There are plans to finally bring commuter rail service out to those South Coast communities that are a little closer to Providence than to Boston, and when they do, all those old Victorian sea captains’ and textile magnates’ houses are going to be coveted by yuppies who work in one or the other of those cities, and the house she bought is going to quintuple in value, so says Lexi. She’s always considered herself a sharp businesswoman and has been waiting all these years to prove it. Regarding his daughter’s self-proclaimed acumen, my father tended to be bluntly derisive. It’s a shame Bert won’t be around to get his comeuppance if Lexi’s real estate gamble pays off. Our parents signed over all their savings and property, everything they had, to Lexi. During those last years when my father was constantly in and out of the hospital, they did need help keeping up with their bills and various other such obligations, and they both knew that after my father was gone, my mother would never be able to handle those tasks alone, so Bert had to teach Lexi how to do it. I know Mamita, especially, was worried about my sister’s sometimes unstable employment and life situations and was determined to give Lexi some security but with responsibilities too. Those decisions freed me to be an aloof son and an even more aloof brother, almost always living far away, in Mexico, Central America, stints in Europe. Meanwhile Lexi has taken care of our parents, often a full-time job, first our father, whom she says she hated through his last years, and now our mother, whom she loves with what it’s no exaggeration to describe as “total devotion.” Look, Lexi deserves everything my parents have given her. I don’t resent her for that, not even a little, possibly for some other things but not that. I wouldn’t have traded the freedom with which I’ve been able to live my life for nearly anything.

As I emerge off the Penn Station elevator into a lightening gray dawn, the giant Corinthian colonnades of the post office building create the illusion of a grand boulevard, and an invigorated optimism floods me, like it’s the first morning of a long-awaited trip to Paris. Even with the time I lost looking for the novel, I’m early enough to walk up Eighth Avenue a few blocks to the salumeria to get a hero sandwich for the train. The trip between New York and Boston is almost five hours long, as long as a flight from JFK to Benito Juárez, and traveling with a good sandwich makes all the difference. Hombre prevenido vale por dos, Gisela Palacios always liked to say. She loved those old-fashioned country grandma sayings, though she could barely cook a quesadilla. Whether it made him worth two men or not, planning ahead like this is just the sort of thing my father, both a scientist and a sandwich man, always did, though he would have found an old-style Jewish deli, corned beef on a bulkie or else tongue. Bert always drove, I can’t even picture him sitting on a train or a subway. He only flew when he had no choice. The last time he made that end-of-winter drive from Florida back to Massachusetts, he was eighty-seven. He was passing through one of the Carolinas when, before pulling into a motel for the night, he stopped for dinner in one of those highway national chain steakhouses and only discovered the unpaid restaurant bill in his pocket when he got home. He mailed the bill with a check to the steakhouse along with a note of apology, explaining that the reason he’d left without paying was that he’d been tired from a long day of driving; he had to admit that at his age he no longer had the same stamina as when he was younger. Barely a week later a letter came in the mail from the restaurant’s manager, who wrote that nowadays it was rare to encounter such an honest American traveler, and he included a certificate that would let Bert eat for free in that steakhouse in perpetuity. Free steak for the rest of his days! But he’d already sold his little Lake Worth condo so that he could live year-round on Wooded Hollow Road. My father would never drive through the Carolinas again. He wasn’t always that honest, either, though he had a way of giving the impression that he was, with sort of an Abe Lincoln look of homely integrity, dangling rail-splitter arms. So Mamita took him back for that last time, and though she was nearly twenty years younger, the repercussions on her own health of those next six years of looking after and having to deal with Bert every day would be dire.

While the counterman prepares my sandwich, I sit at a table, quickly downing a small cup of coffee and a cup of yogurt, getting a healthy start to what’s going to be a long day, and open the Muriel Spark novel to the first page: “Long ago in 1945 all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions.”

Yesterday evening I thought it was already over with Lulú López. Even though we’ve only gone out a few times, it’s the closest I’ve come to any kind of romantic relationship in five years, since things ended once and for all with Gisela. But then last night Lulú sent that maybe-it’snot-over text message: Hurry back, we’ll ride bicycles, etcetera. I can’t pretend I don’t care what happens between us, but I do try to keep up a fatalistic interiority. But I’m excited about this trip to Boston, in fact, I’ve started out a day earlier than originally planned just so I can meet Marianne Lucas for dinner tonight in the South End. When she wrote to me out of the blue a couple of weeks ago on Facebook, we hadn’t spoken, or had any kind of communication since tenth grade, thirty-four years ago. She’s a family and divorce lawyer now and divorced herself. In one of her FB messages, Marianne wrote that she’d decided to try to contact me after hearing me on NPR. I was talking about José Martí and his years living in New York City, the focus of the novel I’ve just finished, which is not a strictly biographical novel. The House of Pain I’m calling it. No argument from me that it might make a suitable title for the biographies of so many of us out here on the sidewalk this morning coming out of and headed down into Penn Station, who’ve also spent consequential time in a house of pain. It’s not a title anyone would ever use for an actual biography of José Martí, those always have to evoke heroism, martyrdom, literary and political genius, or strike the “Yo soy un hombre sincero” chord. But The House of Pain is a perfect title for my novel, the major part of which takes place inside a boardinghouse during a couple of the sixteen years Martí lived in New York City, back when he was a poor immigrant exile, tirelessly hustling freelance journalist, translator, private Spanish tutor, poet, and revolution plotter, all this over a decade before he finally found his martyr’s death on his one-man, one-horse charge against Spanish troops on a beach in Cuba. I handed the novel in to my publisher just before I left for Argentina. It’s only 182 double-spaced pages long, but it took five years to write. It required a lot of research, I even went to Havana and spent a few weeks in archives there. I needed to learn everything I possibly could about Martí in order to identify the gaps where there was no historical or written record, and let my imagination go to work inside those. One draft was 500 pages long. That was followed by another of 278 pages that I handed in, but it was a botch. My editor, Teresa Fijalkowski, was hard on it; that is, while she was fine with latter parts of it, she stuck it to me about the first third. So many voices and who’s talking and whose thoughts? Look, Teresa, it’s simple, I explained. The narrative spine of that opening section is Martí on a long walk through the city streets to his boardinghouse, where his wife, small son, and the boardinghouse owner’s wife, secretly pregnant with Martí’s child, are all waiting for him to come home. He’s trying to work out in his thoughts how everything in his life has gotten so completely fucked up, and inside his head he’s talking to his wife and to his lover and to other people, and he’s even trying to imagine what they’re saying about him. All of that trails after Martí on his walk back to the boardinghouse like clouds of consciousness that settle onto the page as if into wet cement as fragments of narrative and story. Teresa cracked a half smile, gave me one of her steady ice-cave stares, and finally, with perfect dry comedy, cracked: The dubious gift of consciousness, now I get what Blanchot meant. I said, And it’s just my luck to have the only book editor in New York with a PhD from Oxford in critical theory. I wrote my thesis on Auden, said Teresa. But of course we read theory, so what? Frank, there’s a lot of turmoil, a lot of pain in that boardinghouse, I get that, said Teresa. But I’d like to sense how they’re experiencing it, one character at a time, right from the start. Martí was a hyperconsciousness, I argued, so voluble he was nicknamed Dr. Torrente, and he had more going on in his brain, in his life, than maybe anyone else living in New York City at that time. I spent another relatively monkish year in Mexico City working on the novel. I needed to fasten my prose not only to Martí’s heartbreak and torment but also to his wife’s, her life obscured by over a century of blame. You think Yoko Ono had it bad, imagine having Fidelista Communists and Miami Cuban right-wing fanatics all blaming you for the Cuban Apostle’s failed marriage, separation from his son, and years of complicated private torment. It’s my lost skinny ugly beautiful book that lived with me through my own most trying years and finally found its way home, my best book, The House of Pain. In about nine months maybe it will be displayed over there in the train station bookstore, facing out on the new-books table, ideally positioned between Zaro’s bagels and the men’s room. Maybe someone will buy it to read on a morning train to Boston a year or so from now, and I’ll be taking that train again, and for the first time in my life I’ll get to see someone reading a book of mine in public.

Call it Pain Station, too, I think, having just taken my Louis Kahn memorial pee at one of the urinals in here, can’t think of a bleaker place to die of a heart attack like the great architect did than this always-stinking filthy men’s room. I always picture his final collapse onto the floor like Nude Descending a Staircase, a paroxysmal grandeur but with a short, elderly Jewish man clutching his chest and falling, white shirt stained with airline salad dressing and coffee dribbles—he’d flown into JFK and come to the station to catch a train—his final breaths witnessed by drug addicts and the homeless psychotics who’d be in federal or state mental hospitals instead of sheltering in train station bathrooms if such hospitals still existed. Kahn was on his way home to Philadelphia from Bangladesh, where he’d just built his masterpiece, the Bangladeshi capital’s National Assembly Building, ancient sacred monumental grandeur reformulated into rigorous vanguard modernist design. After creating one of the most beautiful, spiritually stirring public spaces of modern times, Kahn came home to die in one of the ugliest and most demoralizing.

Here in Pain Station, passengers wait to board their trains in a grimy plastic-and-linoleum arena enclosed by numbered east and west gates while heavily armed soldiers in camouflaged combat fatigues and bulletproof vests stand guard or patrol the floor, bomb-sniffing dogs, too, all of us jammed together as if into a ravine. As our train’s scheduled departure time approaches, if we’re Pain Station veterans who know how it works, our eyes fix on the clacking departure board, waiting for our gate to be posted, white numerals and letters, 7W, 11E, 13E, west on the left side, east on the right. Because these are posted several crucial seconds before they’re announced over the station speakers, clued-in passengers get the jump and surge toward that gate; when it’s obvious the train is going to be crowded, it’s a stampede. There: 9W! In this split second my eyes drop from the departure board to the back of the hand that my mole is on and I start moving. In my dyslexia I rely on this mole to tell me which way is left. Trapped inside that instant of panic—turn left!—I only have to look for the directional mole in the dead center of the back of my left hand to know which way to go. That Francisco can’t tell his left from his right; oh, but he can, thanks to his directional mole.

“The 8:05 Northeastern Regional Amtrak train to Boston is now ready for boarding, please proceed to gate 9W and have your tickets out.” But I’m already at the gate, near the front of the line.

Coming off the escalator I walk quickly ahead, passing passengers proceeding single file alongside the train, clackclackclinkclacking all the way to the next to forwardmost train car. This cold March morning is probably not going to be a heavy travel day. Should have a seat to myself all the way to Boston.

* * *

So Marianne wrote to me because she heard me talking about Martí on the radio. But why, really? When I discovered her message on the computer screen, my first reaction was that it couldn’t really be from that Marianne or that it must be a hoax. Then I felt like I’d been waiting for a message from her practically forever. But we were only close for a few months back when we were fifteen. “It’s funny,” she wrote in her message, “what survives for more than thirty years.” So what survives? She didn’t say. What about those few months could still matter to her? Maybe I’m making too big a deal out of it, and this, my excited curiosity, is just phantom-limb nostalgia for the reciprocated first adolescent love I never experienced. Does Marianne still recognize herself in that long-ago girl, and does she think I am still anything like that boy? Sometimes I wonder if it would have made a difference in my life, to have had a high school love. Back in tenth grade, it was Ian Brown who provoked our not even speaking anymore. It was Ian, in middle school, who gave me the nickname Monkey Boy. Marianne is going to want to talk about Ian tonight, I know she saw him at the last reunion. “Same asshole as ever,” she wrote. Just remembering Ian makes anger flare through me. I rock back in my train seat. Whatever, man, that was all more than thirty years ago. Like if it weren’t for Ian Brown, you’d be happily married now, a dad even, instead of a man too ashamed to show up at a high school reunion because he doesn’t want them to know that at nearly fifty he’s a lonely grown-up Monkey Boy like they all would have predicted for Frankie Goldberg. A grown-up monkey on the cusp of fifty who hasn’t had a lover of any kind since his relationship with Gisela Palacios ended some five years ago in Mexico City. A stretch of loneliness that was starting to feel fucking eternal. But things have unexpectedly picked up since I moved back to New York. As if change might really be in the offing. We’ll see.

* * *

Out of the long tunnel, the train is passing through Queens, and the pale morning light gives the monotonous if jumbled sprawl here the look of something covered in grime being slowly hosed off, revealing a submerged radiance like a soft, youthful glow in a face where you wouldn’t expect to see it, an old or sick person’s face. I slowly finish my coffee. The sandwich rests in my backpack.

It wasn’t just Monkey Boy. I had another nickname before that one, Gols, pronounced gawls. I wonder if Marianne remembers Monkey Boy or Gols. Even though it was only inspired by a sixth-grade teacher talking about the Franks and the Gauls as he stood in front of a map of old Europe, it was a creepy-sounding name, it sounded like crawls or ghouls. Even now, it’s painful to consider why Gols struck kids as so apt for me, but it’s not really a mystery. When I was almost three, living with Mamita in my grandparents’ house in Guatemala City after she’d left my father for the first time when I was around six months old, I’d caught tuberculosis, and whether that was the cause, something grossly impeded my physical development. In photographs from elementary school, I’m an emaciated, sallow weakling, sunken eyes, wooly hair, mouth dumbly hanging open, huge ears, a feeble boy raised in a damp, dark cellar by spiders who feed him moths, a boy called Gols. Eventually my limbs began to fill out; slowly I got stronger. By eighth grade I’d even score a few match points for my middle school track team; a year after I’d transform into a boy who won 440 races; in tenth grade, which is when high school began in our town, I’d even try out for football. Yet Gols stuck to me. I had other nicknames, too: Sleepless because I so often looked sleepy, lost in a demoralized stupor, Chimp Face, Pablo, but Gols was the one I really hated.

* * *

That snowy morning after Grandpa died, walking with my father through the town square to the bakery that sold bagels, rye bread, and challah, a snowball hit the back of my father’s herringbone fedora in a burst of snow, the hat jumping up and landing almost jauntily tipped forward atop his head, gloved hands clapping falling eyeglasses to his chest. He shoved the glasses back onto his nose, pushed back his hat, and we turned and saw the boy who’d thrown the snowball, Ricky Rossi from my sixth-grade class, sneering baby face in a bomber hat with hanging earflaps. Pitching arm cocked as if about to hurl another as he lightly skipped backward on the snow-covered sidewalk, he shouted, Jew! The boy beside him, who I didn’t even recognize—long, waxy, potato-nosed face under a wool cap pulled low—loudly screeched Gols, and they turned to each other to laugh as if in triumph and spun and ran away. A Norman Rockwell painting, quaint New England town square in prettily falling snow, rascally boys being boys. My father, a half snarl on his face, looked at me, and I tensed, certain he was about to ask, Gols? They call you Gols? What in hell does that mean, Gols? But he turned back toward the bakery into his composed silent grief. With his fedora, thick-framed eyeglasses, and weighty angular nose, he did look pretty Jewish. I’d hardly known my grandpa. He was pretty out of it in his last years and lived in a crowded multistoried Jewish nursing home that I so hated to visit I was only occasionally forced to, though my father went nearly every weekend, often accompanied by Lexi. Grandpa, born in czarist Russia nearly a century before, in the Ukraine, had grown up among Cossacks and pogroms. What must my father have made that morning of having a snowball thrown at his head by a punk kid shouting Jew?

My father liked to make emphatic statements about character. Things like: You can’t hide not having any character, Sonny Boy. If you don’t have any, it always shows. Like a hypochondriac trying to check his own pulse but unable to find it, I anxiously dwelled on this mystery and problem of character. Standing there in that pretty snowfall, those boys having just thrown that snowball and shouted “Jew” and “Gols” and my father looking at me like that, I felt that it was me who’d been exposed as lacking this thing called character, who couldn’t even imagine, no matter how much I brooded afterward, what I could have said or done in that moment that would have demonstrated character, so that even remembering it now I feel frustrated by this sense of an insurmountable lack that seems to have a name; that name must be Gols.

“So why don’t you ever come to any of our high school reunions?” Marianne asked in one of her messages. How long would it take me to answer that. Longer than it will take to eat my sandwich.

That year of eighth grade especially, Ian Brown used to invite me to his house, hectoring me on the phone to come right over, and I’d get on my bicycle or walk. If I cut across that side of town by walking on the railroad tracks, I could make it in about forty-five minutes. The Browns lived out by Fuzzi Motors and the House of Pancakes and the synagogue, in the same kind of split-level house that we did, common in the newer neighborhoods, plasterboard walls and doors, no basements, skeletons of wooden beams resting atop concrete foundations. Ian never came over to my house on Wooded Hollow Road, painted a bright tropical blue with black wrought iron Spanish grillwork underneath the front windows, my mother’s touch. I was happy to have a friend who was as popular at school as Ian, it made me feel as if our destinies were auspiciously linked. That seemed even truer when our school system selected—or classified—both Ian and me as underachievers, meaning that if we didn’t want to be held back, we would have to attend a special summer program. Was there anything good about being an official underachiever? To my father, it was one more shaming of his son for his infuriatingly stubborn refusal to try to do better in school, one more signpost on the bad road he was always announcing in that lowing tone of doom and lament that I was ineluctably headed down: You’re going down a bad road, headed for an ineluctable bad end, Sonny Boy. That’s how I knew the word “ineluctable,” surely no other eighth grader used it as much as I did. But if being an underachiever actually meant you were somehow a superior person, which according to Ian it did, you shared a bond with a fellow underachiever, you were like members of a secret club who understood the workings of the world in a way people outside it didn’t. According to Ian, we didn’t really have to worry about the future, high scores on our SATs would get us into college no matter what. When we took the exams our natural underachievers’ intelligence would take over. I didn’t really buy that theory. I was sure my low grades were going to count against me no matter how I did on the SATs, but I kept it to myself; even when you disagreed with Ian about something minor, he’d ridicule you until you took it back. Ian’s elastic grin, the way it narrowed and stretched his greenish eyes, gave his face an ecstatically diabolical expression. But he was a handsome kid with a mop of sandy hair who could always create a circus around himself. On Halloween he came to school with his face dyed red with food coloring, carrying a jar of mayonnaise under his arm, and went around clapping his own cheeks to make the whitish goop squirt from his mouth into the paths of squealing girls and onto their clothes. Even the pretty young social studies teacher Miss Turowski came out into the hall to gape at Ian doing that, and I saw how she lifted her hands into her thick blonde hair and looked around appalled, then went back into her classroom shaking her head, sort of laughing. No one else but Ian could have come to school on Halloween as a perambulating phallus and gotten away with it like he did.

* * *

That’s some goddamned friend you picked, that Brown kid, I remember my father blurting as we drove somewhere in the Oldsmobile one day. His father’s in B’nai B’rith, I see him when he comes to meetings. He’s the one owns that toilet store out on Route 9, wears those pastel jackets and dyes his hair, a regular Liberace, that one. No wonder his kid’s a good-for-nothing, thinks it’s a joke to be forced to go to a summer program for lazy kids going goddamned nowhere, big joke that is, and you running after him every time he snaps his fingers.

And me, running after Ian Brown every time he snapped his fingers. It makes me feel sick to remember all this.

Ian’s father did own a bathroom fixtures store in a small shopping plaza on Route 9. Mrs. Brown worked as the personal secretary to the owner of a Boston liquor distillery called Old Yeoman. There’s one night that I especially remember, when Ian must have snapped his fingers and I’d gone running over, and Mrs. Brown came and sat with us at the kitchen table after they’d all had dinner. She was wearing pajamas and a thick quilted bathrobe, her hair a Phyllis Diller mess, cold cream spread like cake frosting over her face, her nose like the carrot on a snowman. She was smoking menthol cigarettes and sipping Old Yeoman mint-flavored vodka straight on the rocks.

Gleefully grinning Ian proclaimed: Ethel says you’re a sickly looking boy. He called his mother Ethel. A sickly little monkey boy. Come on Ethel, don’t deny it, and Ian rocked back in his chair as if propelled by his inhaled wheezy laughter, slapping the tabletop with his big basketball player’s hands.

Mrs. Brown wanly smirked at her son, thin eyebrow raised, opposite eye narrowed, and she exhaled a long plume of minty smoke. Her chin was trembling.

Ethel knows you got tuberculosis down in banana land when you were a baby, said Ian. And you don’t take the TB tests at school because they’re going to be positive. So you don’t even know for sure that you’re cured.

Mrs. Brown’s eyes fixed on me from inside her white mask in a way that suddenly sickened me. I should have heeded my mother’s advice and never told anybody about having tuberculosis, but to have told Ian! The TB tests took place behind a curtain. Nobody even had to know I didn’t take them because when the nurse looked at my medical record, it informed her that my skin would react with a positive.

Come on, show some character, I silently urged myself, then said as strongly as I could: I’m cured.

That made Ian laugh. I don’t know, he said. Ethel thinks you’re still sick and that it might be contagious, right Ethel?

Mrs. Brown laconically said, Oh Ian, stop that. Don’t be such a jerk to your friend.

You’re going to catch a sleeping illness from that sick little monkey boy. That’s what you always say, Ethel, admit it, said Ian, even sounding somewhat accusing.

Alright, boys, Mrs. Brown slurred wearily. I’ve had enough of your joking around, what a couple of pranksters. I’m going to bed. She took a last drink of her vodka, stubbed out her cigarette, got up without saying goodnight, and headed down the hall, her big pink shaggy slippers, thin slumping shoulders, and wild hair making her look like a Dr. Seuss character.

So, really, it was Mrs. Brown who named me Monkey Boy.

What was Bert doing in B’nai B’rith anyway? He wasn’t religious. Most years he’d go to synagogue for maybe one High Holiday service at most. I never heard him say a word, fond or disparaging, about his Fiddler on the Roof shtetl roots. Even his youngest sister, my aunt Milly, born in Dorchester, spoke some Yiddish, but if my father did, he never let on. Once as a boy when I asked him why he didn’t love Russia the way my mother loved Guatemala, he answered with a wolfish snarl: Why the hell would I have any love for that goddamned country. They didn’t want the Jews there, our family and all the others that got out alive were the lucky ones. He’d probably joined the local synagogue’s B’nai B’rith to make some friends in our town, expecting to find other men he’d be able to talk to like an old-time Boston tough guy about horse racing, bookies, sports teams, forgotten local athletes, Democratic politics. Except the Jews in our town were of a younger generation and milder types than Bert: accountants, administrators, salesmen, a dentist or two, or else the owners of small businesses like Mr. Brown; dutiful dads, and Friday night synagogue goers, most of them; a few even with hippie-style affectations, denim shirts and bell-bottoms, long bushy sideburns. Bert never put on a pair of blue jeans in his life. Most of my friends, from college years and after, got a kick out of Bert and his old Boston tough Jew ways, and some had a hard time believing the terrible stories I’d tell about him. Our neighbors, especially once we’d moved to Wooded Hollow Road, all seemed to like him well enough too. Anything they might have glimpsed of his violence with me, they probably thought I was getting what I deserved. It wasn’t as if that argument couldn’t sometimes be made.

The train slows, allowing passengers to linger, through the windows, over the ruin and splendor of Bridgeport: old factory buildings, many with bricked-in or gaping windows; tall smokestacks, some exuding black smoke; container cranes and storage tanks, a few berthed ships; the greasy sheen of canals and stagnant inlets under concrete highway overpasses; slummy apartment buildings and homes, plywood-covered windows gray with moisture or rot. Farther on, after we’ve left the station, a CasparDavidFriedrich graveyard with crooked gravestones, bare, black, twisted trees, enclosed by an old wall of stained, crumbled masonry and shriveled vines.

The Ways was what the rich-people part of our town was called, out near the Charles River and the border on that side, because it was only out there that the streets had names like Bay Colony Way and Duck Pond Way. Not many if any Jews lived out there. The various Ways turned off one or the other of a pair of sparsely settled avenues to loop past houses built on adjoining lots as in the town’s other subdivided neighborhoods, except here the houses were much larger, none exactly alike, and some very unalike, and they stood far apart in yards that were like medium-size parks with their own stands of pines or islands of trees, with thick forest coming right up to the edge of backyards. But until the infamous Arlene Fertig night in the spring of eighth grade, I’d never seen any of those houses from behind, even though every morning before school I bicycled through the Ways on my paper route, riding at least part of the way up long driveways to snap tightly folded newspapers at front and side entrances, trying to make them fly end over end and land flat at the foot of doors, and keeping score, one side of the street against the other. The houses on the Ways had spatial depths I found it hard to imagine a house possessing. What was in those humongous basements? Movie theaters, indoor swimming pools, bowling alleys? Even the basement of our small ranch house on Sacco Road, where we’d lived before Wooded Hollow Road, had seemed kind of limitless to me, especially on the other side of the paneled bedroom that my father built for Feli when she came from Guatemala, sent by Abuelita to be our housekeeper and to help take care of Lexi and me, that area of raw cement where my father’s massive pine carpentry table and the clothes washer and dryer were, pink fiber insulation wadded like cotton candy between two-by-four beams and into the ceiling, and the storage area at the back, a spooky tunnel of luggage and stacked cardboard boxes where when I was small I liked to hide for hours, and down at the basement’s other end, a furnace like an iron dragon, a blaze roaring in its belly through the winters.

Arlene Fertig was the first girl I ever kissed. It comes back like this whenever I’ve been thinking about Ian Brown. In my memory they’re linked, Ian and Arlene and later Marianne. Arlene was from the same neighborhood as Ian. Romance had been building between Arlene and me in the ways it does in the eighth grade, flirty smiles, cryptic comments from other girls, slow dancing with her to “House of the Rising Sun” at our middle school’s afternoon dance, the warmth of her waist in my hands through her corduroy dress, her hands on my shoulders, her freshly shampooed hair that fell midway down her back, straight but not fine, tingling against my cheek. When the song was over she thanked me in her slightly hoarse voice and I speechlessly slunk away, stunned by the novel overload of sensations. Black bangs over darkly made-up eyes gave her a precocious look, and she was so slight that when she hurried through the halls at school she looked like a running marionette. Once, between classes, when we were trying to have a conversation, she said, My hair is too heavy. It’s making my head ache. Do you think I should cut it all off? She seemed so sincere that I was too confused to say anything. In June, only a couple of weeks left in the school year, I was invited to Betty Nicholson’s party on Duck Pond Way, the first and only time I ever saw a house out in the Ways from the back. Breathing in the early summer lusciousness, looking across the lawn toward the tree line at the fireflies hovering out there, hearing the yammering of tree frogs and crickets, I had the impression of visiting a plantation estate in Guatemala. Arlene and I danced to some slow songs on the torch-lit patio: “Crimson and clover over and over.” One, two, three, go for it. I gave her a quick kiss on the warm flesh of her neck and turned into a trembling tree inside, and she lifted her head and stared into my eyes, an assertiveness like a tiny flame in each of her dark irises, and her small red mouth broke into a smile like a childishly happy and excited strawberry; that’s how I described it to myself later that weekend, silently going over every detail of what had happened. Holding hands, we slipped away through a row of tall evergreen hedges into a neighbor’s backyard where, in the nearly pitch-dark, we embraced and lowered ourselves, already kissing, down into the plush grass, me partly on top of her, and made out. I don’t remember for how long; it could have been five minutes or twenty. The lawn’s nutritious smell also held something stinky, a mix, I realized, of manure and moist soil that grew stronger the longer we lay there. There was just enough moonlight to see that her eyes were closed, her head turning side to side in tempo with the swirling of our tongues, her little hawk nose rubbing and bumping mine. I love you, Arlene, I whispered, I’ve loved you all this year. Arlene, with her lips against mine, murmured, Me too, me too, me too. A minute or so later she hoarsely whispered, We should go back. I remember how after we’d stood up, she reached behind her to rub her dress and brought her hand to her nose and sniffed it, but neither of us said anything about the fertilizer smell. We stepped back through the shrubbery, toward the torches and patio, and she stopped to put on her shoes. She laughed quietly and said, You have lipstick all over your face. She licked her fingers and rubbed them vigorously on my skin. You should go wash your face, she said. I obeyed, slipping quickly into the bathroom off the patio. At the sink I grinned in proud near disbelief at my reflection in the mirror, so smudged by lipstick that it looked smeared with red poppy petals.

Making out with Arlene meant I was going to have a girlfriend, I was sure of it. She was going away to camp soon, and I was headed into the underachiever program. We only had to make it through summer and by fall we’d be discovering love and sex together in the woods after school, over at each other’s houses when no one else was home. We’d stand making out on street corners oblivious to passing traffic like the teenage couples you saw all over our town, talking and laughing with their foreheads touching. Maybe by Thanksgiving we’d even lose our virginity together, like only a few of our classmates, not including Ian Brown, supposedly already had. When I got to school that Monday morning, just before the homeroom bell rang, it seemed like everybody was waiting for me, though that really couldn’t be true, there couldn’t have been that many seventh and ninth graders waiting for me. What I do remember is stepping through the doors into the wide lobby by the cafeteria and hearing howls and shrieks of excitement, laughter and shouts about a monkey and a banana. I saw Arlene standing between Ian Brown and his best friend, Jake Rosen, our middle school’s football star even as an eighth grader, and Ian was holding her by the bicep. Arlene’s face was weirdly distorted, like a rubber mask of her own face hanging in a tree, her usual sweetly shy smile replaced by a grimace-grin, as if she were about to explosively sneeze. Her hands flew up as if to pull that mask off, and she turned and fled, Ian spinning to watch, her friend Betty Nicholson chasing after her.

Supposedly, Arlene had said that when she was making out with me, she’d felt like a banana being chomped on by a monkey. That joke electrified the school. But I’ve never believed it was Arlene’s joke. It just didn’t make any sense to me that she would have said that. I think it was Ian who came up with it and that he and Jake told everyone it was Arlene. In all the classes I went to that morning, I elicited snickers, sharp grins of malice, looks that mixed pity and hilarity, a few just pitying. Kids made banana-eating gestures when they saw me coming in the corridors or made screechy monkey sounds, some jouncing their hands under their armpits. In one class after the next, I sat stiffly in my seat as if trapped behind the steering wheel in an invisible car crash, that dazed sensation of wondering: Is this really happening? I felt as if I’d walked out of myself, leaving behind an eviscerated container. That horrible sensation of a vacated hollowness that follows one of those enormous disappointments that can seem to take over and permeate everything. Whenever I have a day like that, I remember my first kiss.

Two teenage girls who I noticed when they boarded at Bridgeport—both Latina looking, one a short-haired sprite, bright lipstick, the other long-haired in an oversized scarlet hoody—are sitting a few rows behind me and talking about, as far as I can tell, another girl whose name is Pabla, their giggles foaming over like a boiling pot of squiggly pasta. And now one sings out, with more hilarity than mockery: Pabla! Who names their daughter Pabla? The other girl says: It’s her father who’s Puerto Rican. Her mother’s a white lady from here. And the first: But Pabla? So how stupid could her father be? Pabla! They laugh some more.

I’m grinning to myself too. Poor Pabla. I’ve never known anyone named Pabla. It sure is not the feminine version of Pablo, not in any common usage anyway. I once knew a Consuelo who told me that all her life in the United States people had been calling her Consuela. Consuelo literally means “consolation”—Consuela, “with shoe sole.”

But I’ve just remembered another Pabla, in Krazy Kat I think it was. Krazy, for once distracted from his spurned love for Ignatz, meets a lively cat with amorous eyes named Pabla in a tree. They frolic like squirrels in the nearly bare boughs, but suddenly Pabla slips from a branch and instead of plummeting drifts down into a pile of raked leaves. Krazy follows, leaping into the pile, at first playfully searching it for Pabla but then more frantically, snatching up leaves one by one and flinging them aside until not a single leaf is left. No sign of Pabla. Alone again, wails Krazy, natch-roo-lee.

When I wasn’t even a year old, my mother split from my father and took me back with her to live in her parents’ house in Guatemala City. She’s never told me a reason why. All my earliest memories are set in my abuelos’ house, the same one Mamita and her brother, Memo, had grown up in, an old-fashioned Spanish colonial with a stone patio in the middle, dark cool rooms with polished tile floors, and usually shuttered, barred windows facing the street; heavy dark furniture in the living and dining rooms, the Virgin and saint statues in glass cases, the caged finches and canaries Abuelita kept in a small side patio; the thick, woven cloth huipiles always smelling of tortillas and soap that the servant women wore, the older one with a wrinkled face and the young one I spent most of my time with, the recollection of her ebony Rapunzel hair seemingly coterminous with her enveloping kindness and quiet giggles; the memory of sitting in my bedroom’s window seat and passing my toy truck out through the bars to an Indian woman who took her baby boy out of her rebozo and set him down on the patterned old paving stones of the sidewalk so that he could play with the truck and my astonishment that he was naked. A memory like the broken-off half of a mysterious amulet that can only be made whole if that now-grown little boy remembers it, too, and we can somehow meet and put our pieces together. I don’t even remember if I let him keep the truck or not, though I like to think I did. Not all that likely that he’s even still alive, considering what the war years were like for young Maya men of our generation. Who knows, maybe he’s up here somewhere and even has children who were born here.

Mamita must not have loved my father enough anymore, or must have convinced herself that she didn’t, to want to live with him and raise a family. It’s not like Bert was cheating on her and that’s why we left. That seems like the kind of thing she would have told us or at least told my sister and Feli; they sure wouldn’t have kept that a secret all these years. We were going to stay in Guatemala and make our lives there. But what misery and humiliation my father must have endured over those two years plus, a long time to be separated from his family; he couldn’t really have been expecting us to come back. Then what large-hearted forgiveness he displayed when he found out that his truant wife and tubercular three-year-old son were returning to him after all. In Boston, I’d at least get better medical care; that was really why we came back, I understood later. My father rolled the dice and decided to move his shaky family out to that idyllic-seeming town off Route 128, where he purchased a ranch house in a neighborhood so brand-new it looked just unpacked from its box, set down between steep hills and ridges, and comprised of only two intersecting streets, straight Sacco Road, where we lived, and bending Enna Road, together running along three sides of a large weedy-thistly rocky field called Down Back. That was the house, already partly furnished, that my mother and I came to live in around Christmas. My father must have met us at Logan Airport and driven us to our new home, where he’d put up a Christmas tree down in the basement, right in front of the furnace, a dangerously flammable spot, instead of in the living room, as if he didn’t want the neighbors to be able to see it through the picture window, worried that at the last minute we wouldn’t come back after all, and the neighbors would wonder about that solitary Jewish man who made false teeth for a living and had a Christmas tree in his living room. His older sister, Aunt Hannah, married to a Russian Catholic, Uncle Vlad, had decorated it. Underneath the tree, an orange toy steam shovel awaited me. But I was afraid of my daddy and instinctively rebuffed him, this enthusiastic, grasping man whose marriage and family I’d saved by getting sick. On a recent visit to Green Meadows, my mother told me that. You didn’t like your father, she said. You were afraid of him. Really, Ma? I was afraid of him? And you could tell? Because I don’t remember any of it at all.

A hemorrhaging relapse while playing outside on a hot sunny afternoon that made me vomit sloshing wallops of blood onto the sidewalk—I remember that—my father wrapping me in a blanket and rushing me into his car and also that I got to stay in the Boston Children’s Hospital. Mr. Peabody and Sherman came to visit us in our ward, and my father sat by my bed performing the magic tricks he’d bought at Little Jack Horner on Tremont Street. One was a shiny black top encircled by white flecks, but when my father made the top spin on its special stick, the flecks became a rainbow blur before turning into a row of flying scarlet birds that he said were called ibis.

That’s how these visits with my mother go now, but her occasionally blunt, unguarded way of speaking is a new trait. She’s almost comically the opposite of how she used to be, after all those years of keeping her guard impermeably raised. This new heedless candor is a manifestation of the somewhat premature dementia that has been overtaking her in recent years, possibly the result, doctors now say, of a stroke that wasn’t noticed, a commotion in her brain that caused a tremulous weakness in one leg that was misdiagnosed as a symptom of advancing age. But my sister and I also attributed her decline to the exhaustion brought on by having to tend to Bert during his unrelentingly demanding last years, when being repeatedly hospitalized for an array of health emergencies somehow only fueled his manic, cantankerous energies. By the end, it was Lexi who took over his care, moving home again, adamant that she was only doing it out of concern for our mother. Mamita’s condition seemed related to another medical mystery, that being the most dreadful insomnia that overtook her, when it was as if the more Bert exhausted her, the harder it was for her to get any sleep, her often reddened eyes encircled by darkly puffed skin. It was only when she had to go from the nursing home to a hospital in Boston because of a nearly fatal case of pneumonia and an adverse reaction to her medications that doctors, studying her puzzling medical history, also hypothesized that prior stroke. On my mother’s side of the family, there’s no known history of strokes or heart disease or even of dementia; there are a few old family stories that along with the little bit I’ve found out on my own do suggest that Abuelito was manic-depressive and maybe even schizophrenic. In the nursing home, Mamita’s doctors did finally straighten out her medications. She sleeps better now, though that fog she’s often at least a little bit lost in and from which she does sharply emerge, nevertheless seems to be slowly, ineluctably deepening.