12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

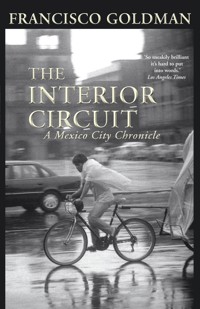

The Interior Circuit is Goldman's story of his emergence from grief five years after his wife's death, symbolized by his attempt to overcome his fear of driving in the city. Embracing the DF (Mexico City) as his home, Goldman explores and celebrates the city which stands defiantly apart from so many of the social ills and violence wracking Mexico. This is the chronicle of an awakening, both personal and political, 'interior' and 'exterior', to the meaning and responsibilities of home. Mexico's narcotics war rages on and, with the restoration of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (the PRI) to power in the 2012 elections, the DF's special apartness seems threatened. In the summer of 2013, when Mexican organized-crime violence and deaths erupt in the city in an unprecedented way, Goldman sets out to try to understand the menacing challenges the city now faces. By turns exuberant, poetic, reportorial, philosophic, and urgent, The Interior Circuit fuses a personal journey to an account of one of the world's most remarkable and often misunderstood cities.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Interior Circuit

ALSO BYFRANCISCOGOLDMAN

Say Her Name

The Art of Political Murder

The Divine Husband

The Ordinary Seaman

The Long Night ofWhite Chickens

The Interior Circuit

A Mexico City Chronicle

Francisco Goldman

Grove Press UK

First Published in theUnited States of America in 2014 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright ©Francisco Goldman, 2014

The moral right of Francisco Goldman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Lines from “Circuito Interior,” page 1, by Efraín Huerta taken from Poesía Completa de Efraín Huerta. Copyright © 1988, Fondo de Cultura Económica. All rights reserved. México, DF.

Lines from “Olor a plastic quemado,” page 27, by Roberto Bolańo taken from El Hijo De Míster Playa: Una Semblanza De Roberto Bolańo by Moníca Maristain. Copyright © 2012, Almadía, Mexico. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Lines from “Manifiesto,” page 172, by Nicanor Parra reprinted with kind permission of Ediciones UDP, Chile.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 616 3

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 971 3

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Jovi

Contents

The Interior Circuit: Summer of 2012

1The Student Driver

2#YoSoy132

3Mayor Ebrard Drives the Bus

4Driving Lessons

5The Driving Project

6The Party Bus

7Interior Circuit Redux

After Heavens: Summer of 2013

Appendix Note

Postscript

Acknowledgments

The Interior Circuit: Summer of 2012

Amor se llama

el circuito, el corto, el cortísimo

circuito interior en que ardemos.

—Efraín Huerta, “Circuito Interior.”1

1 “It’s called love, the circuit, the short, the very short, interior circuit in which we burn.”

1The Student Driver

FROM 1998 TO 2003 I rented an apartment on Avenida Amsterdam in the Mexico City neighborhood La Condesa, dividing my time between there and Brooklyn, where I also had a rented apartment, sometimes spending at least most of the year in one city or the other, and sometimes, during especially hectic periods—teaching job, some other paying commitment up north, love interest in Mexico—moving between the two cities almost weekly. Avenida Amsterdam encircles lush Parque México and the narrow one-way avenue that rings it. On both sidewalks and down its median runs a stately procession of jacaranda, elm, ash, palm, rubber, and trueno—thunder—trees, among others. The median is a stone-paved walkway flanked by packed dirt where people exercise their dogs, by shrubbery and flower beds, and inside the curb at many intersections stand windowed shrines to the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the daytime the avenue is a canopied green tunnel from which you emerge into the Glorieta Citlaltépetl, a traffic roundabout with a fountain in the middle, as if into a sunny jungle clearing.

As Mexico City roundabouts go the Glorieta Citlaltépetl is a tranquil one, with only two streets feeding in and out, Amsterdam and Calle Citlaltépetl, the latter just a few blocks long, also with a tree-lined median. But during the rush hours even this circle gets hectic, as the Condesa fills with traffic, horns blaring and jabbing, cutting through the neighborhood to and from the major thoroughfares that border it. That’s when drivers circling the roundabout from the direction of Parque México and busy Avenida Nuevo León routinely invade Calle Citlaltépetl’s opposite traffic lane for a shortcut left onto Calle Culiacán, about thirty yards down. Whenever one car seizes an opening, making a break for that lane, others, speeding up, follow, in almost festively paraded outbursts of banal traffic delinquency. Many times, before it became automatic to look to my right before crossing, I had to hurl myself back onto the curb.

One late morning, ten or so years ago—the traffic, as usual at that hour, light—as I was walking across the Glorieta Citlaltépetl, I noticed a dark-colored Volkswagen Beetle going around and around it. Probably it was nothing more than that repeated circling that made me stop and watch. Or else maybe, for a moment, I semiconsciously wondered why a taxi—because back then, most of the VW Beetles you saw in Mexico City were taxis—would be going around and around as if the driver were lost in a manner that just circling the roundabout was unlikely to solve, or couldn’t find the exact address on the glorieta that his passenger was stubbornly insisting on, or else was running up the fare on a sleeping or passed-out passenger in this demented way. But I must have quickly noticed that it wasn’t a taxi. Lettering on the VW’s doors identified it as a driving school car. When it went past again I saw that the student driver, his instructor alongside in the passenger seat, was a silver-haired man with a mustache, well into his seventies at least, dressed in white shirt, tie, and suit jacket. The student driver sat erect behind the wheel, grasping it with both hands at ten and two o’clock, his posture, his protruding neck above the tie, giving an impression of elegant lankiness. My memory of his face seems vivid, except the face I recall exactly resembles that of Jed Clampett, the Beverly Hillbillies patriarch, though with a brown complexion. What, I wondered, had inspired this man to learn to drive at his age? His attire suggested that the driving lesson was a pretty momentous occasion for him, or maybe he was just that sort of old Mexican who never went out anywhere unless in suit and tie. I imagined the scene at his home earlier that morning when he was leaving for his lesson, an affectionate and proud send-off from his wife, or maybe an affectionately teasing or ironic one. Or maybe he lived with a daughter. Or maybe it was one of those inertia-defying widowerhood decisions, that he would finally learn to drive, which is almost precisely what, in the summer of 2012, it would be for me. July 25 would mark the fifth anniversary of my wife Aura Estrada’s death. Aura died in Mexico City, in the Ángeles de Pedregal hospital in the city’s south, twenty-four hours after severely breaking her spine while bodysurfing at Mazunte, on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca. She was thirty years old, and we’d been married a month short of two years.

Unlike the elderly man circling the glorieta, I wasn’t a beginning driver. I did know how to drive, but I didn’t know how to drive in Mexico City, where I mostly depended on taxis and public transportation to get around. I could count on one hand the numbers of times I’d tried to drive there, though I’d been living in the Distrito Federal, the DF, as the city is formally but also popularly called, off and on for twenty years. The DF has a population of about eight million, but during weekdays, with so many commuters pouring in from surrounding metropolitan México State to work, the number swells to twenty million. The seemingly anarchic chaos and confusion of the city’s traffic had always intimidated and even terrified me: octopus intersections and roundabouts like wide Demolition Derby arenas; cars densely crisscrossing simultaneously from all directions and all somehow missing each other, streaming through each other like ghosts; busy cross streets without traffic lights or stop signs; one-way streets that change direction from one block to another; jammed multi-lane expressways and looping overpasses, where a missed exit invariably means a miscalculated turn onto another expressway or avenue heading off in some unknown direction, or a descent into a bewildering snarl of streets in some neighborhood you’ve never been to or even heard of before. My most gripping fear was getting lost on an expressway, on the Anillo Periférico or the Circuito Interior, during one of the torrential summer rains, thunder and lightning in the low flat heavy sky like sonic sledgehammers falling on the car roof, and the rain, dense, blinding, trapping you inside a steady frenetic metallic vibration, and even welting hail menacing the windshield, and in a panic making for the first near exit and descending into drain-clogged streets that are suddenly and swiftly flooding, crap-brown water engulfing stalled cars, the tide rising to door handles; newspapers publish photographs of those routine calamities all summer long. Everyone tries, though it isn’t always possible, to keep a distance from the careening peseros, hulking minibuses whose bashed and scarred exteriors attest to the Road Warrior aggression of their notorious pilots, responsible for so many accidents and fatally struck pedestrians that two consecutive jefes de gobierno, or mayors, of the Distrito Federal have vowed to abolish the fleet entirely. Trucks and buses crowd and bully traffic. Electrified trolleybuses inexplicably run down major avenues in the opposite direction from the traffic in their own not always so clearly marked lanes; you just have to know that you’re on one of those avenues and watch out.

I didn’t see how I could ever know enough to drive in Mexico City, that population-twenty-two-million sprawl covering and climbing up the sides of the Valley of Mexico, the world’s third-largest metropolis, with its seemingly countless jigsaw-puzzle neighborhoods and infinite streets. Every taxi driver I’ve ever asked about it admits to getting lost. I’ve ridden in countless taxis that, in fact, were lost, even as we blundered through familiar neighborhoods that I would have guessed the drivers knew too, since I infrequently venture far from the areas of the DF where I and most of my friends live and hang out—neighborhoods, or colonias, that cover a small swath in the lower quadrant of the floor-to-ceiling Guía Roji Mexico City wall map hanging in the apartment I live in now. In this map the DF, inside its scarcely delineated borders, is dwarfed by the metropolitan Mexico City area, in México State, filling the map’s upper two-thirds. Always, when getting into a taxi at the airport, I’m silently dumbfounded, or else kind of awed, by the drivers who seem to have no idea of how to get to colonias Roma or Condesa, the nucleus of my inexhaustible little world, especially since about a quarter of the passengers on my favored evening flight from New York City to Benito Juárez International Airport always at least look like typical residents of those neighborhoods. The taxi drivers have their own horror stories about getting lost (they have other genres of horror stories too), such as dropping passengers off deep inside the maze of a never-before-encountered, poorly lit neighborhood and not being able to find their way out for hours.

There was one night, twelve or so years ago, when I mastered driving in the DF, or at least felt I had, charging a long distance across the city with unself-conscious confidence, effortless control and speed. I’m night-blind and should never drive in the dark without eyeglasses, but I didn’t even own a pair back then. I really shouldn’t have been driving at all, because I was pretty drunk. The car belonged to a Cuban friend, and we’d been at a wedding party in Desierto de Leones, on the outskirts of the DF. My friend, who’d only recently learned to drive and was proud of it, was such a haltingly haphazard driver that I often felt impatient riding with him, silently comparing him to Mr. Magoo. Maybe I was in a hurry to get somewhere that night, or maybe I was envious because he could now drive himself around the city whenever he wanted—we’d been taxi-bound friends for several years—but as we were getting into his car I insisted that he hand over the keys. What I remember is a euphoric ride, racing down Avenida Insurgentes Sur, passing cars, an impression of lights bursting and streaming past and vanishing behind, going superfast, and thinking, maybe even shouting, that I was driving like Han Solo, rocketing toward the Death Star. Ever since, the thrill of that drive had lodged inside me as a challenge and as a rebuke to the argument that it was too late to learn to drive in Mexico City, or that I could never overcome my fear. It must be in me to do it again, I repeatedly told myself, though next time less recklessly. Then I’d remember that elderly man in his suit and tie circling the Glorieta Citlaltépetl in the driving school car and tell myself that of course it wasn’t too late.

Every year, it has seemed to me, grief changes, persisting in shape-shifting ways that, as the years go by, become more furtive. But as that fifth anniversary of Aura’s death approached—a year that would mark a period in which I’d now been mourning Aura longer than I’d known her—the intensity of my grief was, unsurprisingly, resurgent, weighing on me in a new and at times even somewhat frightening way that I didn’t know how to free myself from. There was maybe not much logic to this, but I felt that there was a problem or riddle I had to solve and that somehow Mexico City, or something in my relationship to the city, held a solution. For example, sometimes I told myself that one logical step would be to leave the city and begin anew somewhere else, a city I’d never lived in before, one free of memories and associations with Aura but also one in which I’d be able to escape my complicated role as private but also rather public widower. But whenever I thought it over, I’d decide that leaving was an inconceivable step and that maybe the solution lay in staying. And not merely staying, but going further in, embracing with more force what I’d been tempted to flee, maybe that was how to find a way to live in Mexico City without Aura. The approaching anniversary had more than a little to do with my decision that this was the summer when I was finally going to learn to drive in Mexico City.

I was living in a newly rented apartment in Colonia Roma, though I still had our place in Brooklyn. Often when Aura and I had taken a trip out of New York City, or when we were in Europe, or were staying at a Mexican beach, we’d rented cars and I’d been happy to drive. But I hadn’t driven a car, not once, since Aura’s death, and that did seem to symbolize several aspects of grief, its listlessness, loneliness and withdrawal, its grueling duration. Five years without getting behind the wheel of a car suggested a maiming of the spirit but one that should be easy to repair. I just had to start driving again. But I wondered if I even knew how to drive anymore.

One afternoon in early July, I visited my therapist, Nelly Glatt, in her office in Las Lomas. I hadn’t seen her in about a year. Before Aura’s death I’d never been to a therapist, but within days afterward I was directed by a friend to make an appointment with Nelly, a tanatologa or grief specialist, and I obediently went. I remember that first visit well because all I did was sit or slouch or fall over on Nelly’s couch and sob. Nelly, a queenly, extremely beautiful middle-aged woman with pale blue lynx eyes, a diaphanously ivory complexion, and a manner at once soothing, warm, and direct, did so much to help me get through those first few years. That afternoon we spoke about what the fifth anniversary would mean for me, and about whether or not I was ready to re-embrace life, maybe even love again. When I told Nelly about my plan to learn to drive in Mexico City, she approved. She said it signified I was ready to reassert control over my life, as opposed to allowing it to be controlled by grief as if by self-imposed obligation. Nelly said that something inside me had decided that I “owed” Aura five years. I’d refused to move or allow myself to be moved off that one square in the vast grid of possibility.

Couldn’t learning to drive in Mexico City also be something I was determined to do for its own sake? I wasn’t intending to just get into a car and drive around randomly; I’d actually come up with an elaborate, Aura-like method for carrying out my “driving project,” as I called it. She was a fan of Oulipo-like experimental writing games of formal restriction and chance, and also of the I Ching, as well as a devoted Borgesian. But what if carrying it out was actually more of the same, yet another conjured grief ritual, a desire to maneuver and explore the streets of Aura’s childhood by executing a performance game that she would have liked, all in order to intermingle with her city as I might yearn now to trace with my fingertips the contours of her lips, her eyes, her face? I wasn’t sure. But I had formulated a notion that the driving project had something to do with my relationship to Mexico City, Aura’s city, the city where she died and the place that held her ashes, and that now, because of this, had become my sacred place, and my home in a way no other place ever had.

From the air, on a flight in, what the eye mostly picks out from the megacity’s stunning enormousness is a dense mosaic of flat rooftops, tiny rectangles and squares, and a preponderance of reddish brown, the volcanic tezontle stone that has forever been the city’s most common construction material, also other shades of brown brick and paint, imposing an underlying coloration scheme. But there are also many concrete and metallic surfaces and many buildings painted in pastel and more vivid hues like bright orange, and rows of trees, and parks and fútbol fields, and modern towers rising here and there, in Polanco, Santa Fe, and the august Torre Latinoamericana at the edge of the Centro, and the straight and snaking traffic arteries, beady and silvery in the sunlight, and an infinite swarm of streets. You think, of course, awed, of the millions and millions of lives going on down there. (I reflexively think, as I have for years whenever flying into the city, that she’s down there somewhere, living her mysterious life beneath one of those tiny squares, her too, and also her, Chilangas, female residents of the DF, who over the past two decades I’ve met only once or twice but who left an impression, women who almost surely no longer remember me.) From the air, perhaps because it is such a predominately flat city and almost all the roofs are flat and because so much of it is brown, Mexico City looks like a map of itself, drawn on a scale of 1:1, as in the Borges story “The Exactitude of Science,” which refers to “a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point.”

Supposedly the young Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski (Joseph Conrad), seeing a map of Africa, put his finger in its cartographically blank center, the void of an unmapped Congo, and said, “I want to go there.” An opposite of that map would be the Guía Roji, which evokes Borges’s map sliced and bound into an inexhaustible book. My spiral-bound large-format 2012 edition presents Mexico City’s streets and neighborhoods in 220 pages of zone-by-zone maps; at its front 178 additional pages of indexes list some 99,100 streets, and 6,400 colonias, or neighborhoods. The Mexican writer Alvaro Enrigue told me that when he was a boy an aunt gave him a Guía Roji as a Christmas gift, inscribed, “This book contains all roads.” The Guía Roji also suggests a Borgesian metaphysical limitlessness, a bewildering chaos that is actually possessed of a mysterious order that even those who’ve spent a lifetime exploring the city can only dimly perceive. The Guía Roji may be every taxi driver’s bible but he or she needs a microbiologist’s eye, quick mind-hand coordination, and a strong, intuitive memory in order to use it effectively—i.e., find the way to an obscure destination—along with, probably, apt patience and interpersonal skills for engaging with querulous, frustrated, drunken, clueless, and otherwise unhelpful passengers. For instance, the first page of the index, under the letter A—which, like all the other index pages, has six vertical columns of street names in tiny bold print, each street’s colonia listed below each name in infinitesimal print, with map-page number and map quadrant (B-3, for example) to the right—reveals 82 different Mexico City streets named Abasolo. I didn’t recognize Abasolo as an iconic Mexican name, like, for example, Juárez or Morelos. I asked some of my friends why there were so many streets named for Abasolo, and no one had any idea, though it turns out Mariano Abasolo was a relatively minor revolutionist in the war of independence from Spain. In an exercise akin to counting grains of sand, I took the time to count 259 streets named Morelos in the Guía Roji index; Calle Morelos’s columns are followed by several more of Morelos variations: the numerous Morelos that are avenidas, cerradas (dead-end streets), calzadas (inner-city highways), privadas, and so on. Let’s not count all the streets named for Benito Juárez, far more numerous than even Morelos. As for Calle Abasolo, two separate colonias, both named San Miguel, have streets named Abasolo, one on map-page 246, the other on page 261; so do two distinct Colonia Carmens. There are numbered streets too. Over a hundred Calle 1s; nearly as many Calle 2s. The city has some 6,600 colonias, and fourteen of them are named La Palma and five are named Las Palmas. And so on. Buenas noches, señor, please take to me to Calle Benito Juárez in Colonia La Palma . . . now the fun begins.

Whenever I flip through the minutely mapped pages of the Guía Roji, I like to put my finger down on a randomly chosen page, and then, lifting my fingertip, leaning close, and squinting, discover, in tiny print, the name of the street I’ve landed on—just now, Calle Metalúrgicos, on map-page 133, in a colonia called Trabajadores de Hierro (Ironworkers.) Never heard of it. Though Metallurgists is obviously appropriate for a colonia named Ironworkers, it still seems like a pretty weird name for a street. What’s it like to be a child, trying to incorporate the fact that you live on Calle Metalúrgicos into your sense of the world’s hidden meanings and magic and of your place at the very center of it all? That your street, your colonia, is a magnet, pulling the entire universe down toward you? Turning to the index I find that Mexico City has five different Calle Metalúrgicos, in five different colonias. I look at the gridded Mexico City map on the back cover of the Guía Roji and find the square numbered 133, situated almost in the middle, just within the yellow-shaded northern border of the DF. Green-shaded metropolitan Mexico City, in México State, lies just beyond.

Calle Metalúrgicos, in Colonia Trabajadores de Hierro. What’s it like there? That was the driving game I’d come up with. To use the Guía Roji almost like the I Ching, open to any page, put my finger down, and try to drive wherever it landed. A game of chance and destination, if not destiny. Of course, first I had to learn to drive around Mexico City. Since, technically, I did know how to drive, it seemed redundant and embarrassing to enroll in a driving school, but doing so also seemed a good way to get used to being behind the wheel again while also learning the city’s traffic rules and layout under the instruction of a knowledgeable guide. I’d never learned to drive with a stick shift; I’d driven only with automatic. Learning to drive standard, I decided, would justify enrolling in a driving school, because then I would be overcoming two inhibitions at once. I looked up driving schools on the Internet. I went to the Guía Roji store on a gritty street in Colonia San Miguel Chapultepec, and bought the huge map of Mexico City that now hangs on my wall; my 2012 Guía Roji; and a small, rectangular illuminated magnifying glass that would surely prove crucial for reading those densely intricate map pages, especially if I found myself lost while driving in the dark. I went with my friend Brenda to Dr. York, a trendy Colonia Roma eyeglass shop that also sells secondhand English books. Brenda picked out for me a pair of eyeglass frames that I had outfitted with bifocal lenses, and I also bought a copy of Halldor Laxness’s Independent People, a book I’d been meaning to read for years.

I procrastinated on the driving project, but I wore the eyeglasses all the time. Print was now magnified and clearer. By day the world lost its soft blur. My eyeglasses were a cinematographer who’d mastered the noirish expressionism of Mexico City’s nighttime streets, shadows starkly outlined; street lamps like glass flowers instead of spreading haze; the rediscovery of one-point linear perspective in long, receding double files of softly gleaming parked cars; the intermittently illuminated facades of old and sometimes very old buildings like glimpses into individual personalities that are hidden by day, revealing scars but not secrets, battered but proud endurance, psychotic earthquake cracks, the maternal curve of a concrete balcony holding out its row of darkened flowerpots.

In the late spring and early summer of 2012 I had to travel a lot: to Poland; back to New York; then to Mexico to set up the new apartment in Colonia Roma that I was renting with my friend Jon Lee, a journalist who needed a base in Mexico; to Paris less than a week later; to Lyon, broiling with summer heat; back to Paris and from there directly to Buenos Aires to teach a workshop, arriving to snow flurries and a deep wet winter cold. Then I touched down for a few days in the DF, before having to fly to Aspen, Colorado, for a literary conference. Among my responsibilities at the conference was to teach a two-day morning-long seminar on Latin American and U.S. Latino fiction. Most of the students were adults, many retired. On the second morning we discussed Roberto Bolaño and a couple of his stories. This led to a long conversation about Mexico. The students wanted to talk about the so-called narco war, and many of them had grisly perceptions of life in Mexico, which were not inaccurate but were certainly incomplete. Yes, vast portions of Mexico were currently enmeshed in the nightmare and bloodbath of the narco war launched by President Felipe Calderón in 2006, when he’d made his disastrous decision, partly at the behest of the U.S. government, to send the military into the streets to fight the cartels, which were already doing battle with each other. But Mexico City, I told them, specifically the DF—which is what most people mean when they say Mexico City—was a different story. The DF had been largely spared the catastrophe of the murderous narco war; in fact its homicide rate was comparable to New York City’s, I told them, and lower than that of many other U.S. cities, such as Chicago and Miami. I’d lived there off and on for twenty years, and had witnessed how the city had evolved. A dozen years of fairly progressive and energetic political leadership in the DF, among other factors, I told them, had seen the city become a vibrant, relatively prosperous, uniquely tolerant place, however beset with poverty and other problems, a great world city though entirely idiosyncratic, comparable to no other. People say that Buenos Aires is like a European city, but what other city anywhere is the DF like? It doesn’t resemble any other city. In many ways, I told them, Bolaño’s depiction of 1970s Mexico City, especially in his novel The Savage Detectives, as an inexhaustible, gritty, dangerous, but darkly enchanting and sexy sort of urban paradise for youth, but not only for youth, seemed as true to me now as it must have to him when he’d lived there in his adolescence and early twenties. And I went on in this way, my voice swelling with homesick emotion.

“Oh, come on, what a bunch of bullshit,” a student, a middle-aged physician, barked out angrily, cutting me off. “Everyone knows Mexico City is violent, corrupt, overpopulated, and polluted as hell! How can you be talking about it like that?”

For nearly twenty years, since 1995, I’ve been living off and on in the DF. What living there means now is that I often spend day after day without leaving my block in Colonia Roma, or barely leaving it. In the morning I take the elevator from the sixth floor down to the lobby and say hello and sometimes stop to chat with the doorman, David or Eugenio, and sometimes also the security agents, all drawn from the Mexico City police—that is, the few I’ve grown friendly with—who protect my downstairs neighbor Marcelo Ebrard, who a few months ago, in December, finished his six-year term as jefe de gobierno, or mayor, of the DF. Then I go out the door and cut diagonally across the Plaza Río de Janeiro to the Café Toscano, where I have breakfast—almost always the same, papaya with granola, juice, coffee, or, whenever I’m hungover, chilaquiles verdes—and then I stay to work there, often for many hours. Then I go back to my apartment and try to work some more, until evening, when I like to go to the gym. At night I often drop into a cantina, usually the Covadonga, just around the corner on Calle Puebla, though sometimes the nights extend well past the cantina’s closing hours, taking me to other places, usually within the neighborhood, or not that far from it. Before, when I lived in the Condesa, my life wasn’t so different: going to a café in the morning to start my workday, and then often moving from one café to another—I’m a restless person, too restless, I sometimes think, to have chosen a writing career—counterclockwise all the way around Parque México. Only during the four years that I lived with Aura in Colonia Escandón, where there were no cafés nearby, did this routine vary much. Mostly I worked at home. I didn’t go as often to my favorite cantinas. Sometimes in the evenings I went to meet Aura far away in the city’s south, when she’d been to the UNAM, the great public autonomous university, or visiting her mother—Aura had studied as an undergraduate at the UNAM and her mother worked there and lived near the Ciudad Universitaria.

I’d first visited Mexico City in the 1980s, when I was mostly earning my living as a freelance journalist in Central America, and two or three times traveled up from there to receive payment from magazines by bank wire that couldn’t be sent to Guatemala City banks. I never stayed more than a couple of weeks. I remember, during that first trip, in 1984, attending a clamorous party thrown by the embassy of the Soviet Union in the foreign press club where my friends and I were generously plied with vodka poured from bottles encased in rectangles of ice while being interrogated about our impressions of Central America by cheerfully persistent strangers speaking Boris Badenov Spanish and English. (In Central America I never encountered a Soviet journalist outside Sandinista-ruled Nicaragua, probably because any Soviet journalist who ventured into Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras during those years was likely to be arrested and deported or even killed.) I also remember being taken by a journalist friend up to the Reuters office, seeing my first fax machine, and being dumbstruck, dazzled. An unforgettable kiss outside the Museo Tamayo with a really beautiful girl, an art school student with delicate Mayan features whom I’d met inside the museum and then never saw again. A Guatemalan urban guerrilla subcomandante whom I met with in a seedy tiny hotel room in the center, who received me in his underpants and draped a towel over his lap as we spoke, and who passed me a large manila envelope thickly packed with U.S. bills that I was to smuggle in my luggage back to Guatemala City to hold for a stranger who would come to my door and speak a password. The subcomandante was going to cross back into the country on foot, with guerrillas, and he proudly showed me the multicolored cheap plastic barrettes arrayed on a piece of cardboard that he’d bought to hand out to the women and girls in the guerrilla camp. The subcomandante, as his cover, worked in Guatemala City as a photographer for a newspaper society page, while his clandestine role was to establish contacts with foreign journalists, human rights investigators, and the like, and we’d become friendly. In 1986, I think it was, he was forced to flee Guatemala, to Canada, which granted him political asylum, and I never heard from him, or anything about him, ever again.

A lot of memorable things happened during those first few visits to the DF, but it was a different city then. I traveled there again not long after the cataclysmic earthquake of 1985. There was rubble everywhere—collapsed buildings and lots filled with silent hills of concrete boulders and twisted iron amid the restored urban bustle—and dust was mixed like a thickening agent into the pollution and ubiquitous smell of sewage, with bright sunshine turning the air into a gleaming toxic haze, like a physical incarnation of the smelly, persistent aftermath of sudden death and trauma that ran out of your hair when you showered, and burned your eyes. Mexico City’s south was mostly spared the earthquake’s devastation because it rests atop a substratum of hardened lava flows, unlike the center and surrounding areas, which are constructed over what used to be Lake Texcoco, a vast mushy bed of volcanic clay, silt, and sand into which much of the city has been slowly sinking. Any visitor to the city’s center notices the visibly awry tilting of many monumental sixteenth-century cathedrals and churches—a tour guide sets an empty soda can down on the floor of an old church and the can rolls away. Entire streets and blocks of old buildings, all drunkenly tilting, sinking unevenly into the soft earth. Aura grew up in the DF, in the city’s south, during the years of its pollution crisis, when nearly every winter day brought a thermal inversion emergency, and school was often canceled so that children wouldn’t have to go outside. It was the probable cause of Aura’s sinus problems. She remembered riding her bicycle in the parking lot of her housing complex and an asphyxiated bird dropping dead out of the sky, landing right in front of her wheel.

That first time I ever lived in Mexico City for any considerable length of time was in 1992, with my then girlfriend, Tina. It was her idea that we move there for a while, and she went down ahead of me from New York to find a place for us to live, which turned out to be in the more or less genteel colonial neighborhood of Coyoacán (square 186 in the Guía Roji grid, in the south). Tina found us an inexpensive room in the Casa Fortaleza de Emilio “El Indio” Fernández, the fortress-mansion constructed by Mexico’s greatest Golden Age movie director, who was also an actor familiar to English-speaking audiences as Colonel Mapache in his friend Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. Perhaps not even Cortés had dreamed himself such a grandly triumphant and martial conqueror’s palace as the one El Indio had built. Tina was initially charmed by the place because when she arrived there for the first time the massive wooden doors leading into the broad stone patio were open and a dead horse was being carried out in a wheelbarrow. When Fernández died there in 1986—on his deathbed he said, supposedly, “Heaven is a bar in the tropics full of whores and machos”—he was, or so his daughter Adela Fernández, a writer, has told interviewers, penniless, having depleted all his money to pay for and maintain his Xanadu. Adela had been estranged from her father after running away from home and the macho autocrat at fifteen; he wouldn’t let her have boyfriends, and pressured her to be a “genius.” She returned to live in the Casa Fortaleza with her two children only after his death, and began renting out rooms. The fortress-mansion has high walls built of ash-black-brown volcanic stone, the same stone cut into large bricks for the heavy, fortified-hacienda-style architecture inside, which included a massive watchtower with arched windows, topped by a crenellated mirador. To provide access during the fortress’s construction, El Indio had to carve out a new side street, which he named Dulce Olivia after the actress Olivia de Havilland, whom he had some kind of thing for.

Three seemingly separate residences—did secret corridors or sliding bookcases connect them?—faced the main courtyard, which had a dry fountain in the middle. A broad stone staircase led back into the rest of the mansion, always permeated by the chill of cold stone, and filled with staircases and corridors and rooms and galleries and halls that had once held huge parties attended by Marilyn Monroe and other stars but that no longer seemed to serve any purpose. The whole place had the abandoned air of the ruined presidential palace where Gabriel García Márquez’s ancient monstrous dictator lives out his last days in Autumn of the Patriarch, stray cows chewing on the velvet curtains. The mansion-fort was a mess. There was always dog shit in those long empty corridors, at least that’s how I remember it. Our room was just off that main staircase. “Formerly a guest room,” Adela told us when she showed us in. On its walls were colorful murals of wasp-waisted, long-legged nude woman bullfighters with luscious, pointy breasts, painted by a friend of El Indio, Alberto Vargas, who was famous for his illustrations of pinup “Vargas girls” featured in Esquire magazine, back before Playboy introduced its centerfold. Our horsehair-stuffed mattress was ancient, dingy, really disgusting-looking, but when I said that I would buy a new one, Adela declared that I certainly could not. “You don’t know the great men who’ve left their semen in that mattress,” she said. She then pointed to the big French windows and told us how as a girl she used to hide on the wide stone ledge outside and spy on her father’s famous friends and their lovers. She had seen many immortals fucking on what was now my and Tina’s bed. Anthony Quinn, André Breton, John Huston, Peckinpah, Agustín Lara—she rattled off a list of celebrities and artists, Mexican and foreign, who’d spent nights in that bed. That afternoon, Tina and I walked to the shopping center on the other side of Avenida Miguel Angel de Quevedo and bought a stiff plastic covering, the sort used for child bed-wetters, in which to enclose the sacred mattress.

The enormous windows in our room overlooked a deep-walled, now dry, stone pool in the back garden, which was both lush and desolate. We had a daily visitor on the same ledge from which Adela used to spy—a retired fighting rooster, a beautiful animal with lustrous brown-bronze feathers and scarlet comb and wattles and a furious, stupid stare, who not only crowed but always pecked manically and relentlessly at our windowpanes in the dawn hours, waking us. One morning I opened the window and tried to nudge the rooster off the ledge with a broom, but instead of scooting away he just toppled off the ledge and plummeted, wings fluttering, to the distant bottom of the dry pool. The rooster, it turned out, was blind, his eyes pecked out years before in a fight. He wasn’t injured by the fall, and Adela had him moved to some other part of the property. A tabby cat, with one clouded iris and a mottled nose, came in through the window one morning and adopted us for the rest of our stay. We named the cat Don Bernal, after the conquistador who wrote The Conquest of New Spain. Tina and I were allowed to use the huge Puebla-style kitchen, decorated with blue and white tiles, which in El Indio’s time had produced the Mexican fare for countless lavish parties. It had an immense stove with deep ovens and seemingly as many gas burners as a golf course has holes; though this was also in ruins, and filthy, a few of its rusted burners still worked, and so we did cook there occasionally. Ceramic ollas, the traditional earthenware casserole-like big pots used for stovetop cooking, many probably not washed in decades, were stacked into such tall, crooked, swaying towers that we were afraid to touch them. The Puebla tiles were cracked or had fallen out of the walls. Tina and I spent one entire day futilely cleaning. Recently, on the Casa Fortaleza’s Facebook page, I saw a photograph of the kitchen being restored, the Puebla tiles all in place and pristinely gleaming. It seems that the Casa Fortaleza is being transformed into a cultural center. Tours of the property are offered once a week, some given by Adela, who is now seventy, and, according to a newspaper article, reportedly suffering from cancer but still chain-smoking. I wonder if she shows visitors our old mattress and tells them about the great men and their semen.

When Tina and I were renting our room there, a gothic cast populated the house. I was never sure who did live there and who didn’t, or where those who lived there slept. Adela told me that some of the men I saw, such as the one in late middle age who always looked hungover, sporting traces of blue eye shadow and lavishly long dirty fingernails, had been character actors in her father’s films. There was an almost handsome, jug-eared young man who seemed to be a sort of houseboy. He was obviously mentally handicapped, his dramatic eyes perpetually fixed in a silent movie stare, his garbled speech almost unintelligible. Every now and then a man dressed in charro gear—tight seamed pants, short matching jacket, and sombrero—would call at the door and sit with Adela on the rim of the fountain in the patio, holding her hand as they conversed. She told me that he had been a stuntman for her father when El Indio acted in movies, and that now, during these visits, the stuntman was again standing in for her father, playing El Indio himself, conversing with her, repairing their sundered relationship. Adela was an alcoholic, a heavy pulque drinker. Sometimes women who said they’d been El Indio’s lovers would show up at the enormous doors and pull on the rope to ring the bell that announced visitors. I remember a very pretty woman with long raven hair who came to that door and told Adela that El Indio was her father. Adela always invited the women in and gave them a tour. She lived in what had been her father’s quarters, on the left side of the courtyard. She invited me in to see it only once, and I was surprised at how spacious, clean, and orderly it was, with everything supposedly just as he’d left it: a manly abode with an expensive feel; hues of rich wood, leather, and stone; filled with books, paintings, and other of the director’s personal treasures, probably including some pre-Hispanic artifacts—a room suited to serve as the set of a Dos Equis “Most Interesting Man in the World” commercial. Adela’s daughter, Atenea, a blond, ethereally beautiful girl, lived in the middle residence; she seemed rarely to leave her quarters, and it was rumored that she was ill. (Atenea died in 2002, at the age of thirty-seven.) The son, Emilio, wiry and always sneering, at least always sneering at me, lived on the right. He looked like what in high school we would have called a greaser. There was an old car up on blocks that he and his friends sometimes worked on. They gathered around it at night, drank, built fires, played loud music. Adela’s son and I intensely disliked each other. Our few conversations, always gruff, were usually over household matters such as his having cut off the water supply to our room again. We faced off one morning in the middle of the courtyard, snarling insults and threats, and were moments from coming to blows. I felt committed to it, adrenaline surging, but the “houseboy” raced to our bedroom door to fetch Tina, frantically baying, “They’re going to fight!” and she came running out and put a stop to it.

Adela frequently rented the Casa Fortaleza for private parties and for use as a setting in telenovelas and movies. Some mornings I’d come out of our bedroom and find the courtyard crowded with actors in period dress and film crews and equipment, and I’d help myself to breakfast at the craft services table. One evening when I was coming home women I didn’t know refused to let me past the front doors. The house had been rented for a private lesbian lunar festival party, no men allowed. I furiously insisted that I lived there and had every right to enter, but the women allowed me past only after I promised to stay in my room. Another night there was a party for gay men, thrown, we were told, by the son of an important PRI politician, which was why police had blocked off the street. Back then, almost all the important politicians, even in the DF, were from the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party. It had been governing Mexico since 1929, its candidates’ victories in presidential elections every six years often abetted by widespread electoral fraud, until, in 2000, Vicente Fox Quesada of the rightist National Action Party (PAN) was elected president. Gay life in Mexico City was much more hidden in those days, back in the 1990s, than it is now. Gay marriage is legal in the DF, which has been governed since 1998 by a series of leftist governments affiliated with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) and that have made progressive social policies a focus of their governance and campaigns. The only other place in Mexico where same-sex couples can marry, since 2011, is the state of Quintana Roo.

The party in the Casa Fortaleza that night was a bacchanal, an animated explosion of forbidden and repressed sexual energies. Men roamed the mansion-fort looking for private places to have sex—I would have thought the place offered multitudes of private hideaways, but our bedroom, maybe because of the legendary mattress, seemed to strike many as especially promising. The pulling, pounding, and even ramming against our bedroom door, while Tina and I huddled together in bed, having given up all hope of sleep, went on intermittently for hours. Not long after that night, Tina and I decided that it was time to move out of the Casa Fortaleza, and back to New York.2

During that year in the DF we had made a lot of friends, some who are now among the closest that I have. I don’t remember how I met Paloma Díaz. She was a painter, a feline dirty-blonde from an eminent Mexican family who’d grown up in a large colonial house in Coyoacán with her parents and grandmother, a committed Communist who had a mural of Che Guevara over her bed. Paloma now also had a smaller home of her own several blocks away but seemed to divide her time between the two residences. We grew close, and she introduced us into her circle of friends. I remember long weekend afternoons, eight or so of us all gathered on a big bed in her house, smoking pot, drinking beer, slowly sipping tequila, talking, the hours drifting past, and then later going out to walk around the neighborhood. Most of those friends had known each other since adolescence and even earlier, had dated, eventually had even married each other. It was a relaxed, intimate, kind of sexy, and sophisticated way of being friends that was new to me, my experience of friendship being closer to a carousing, somewhat girl-shy antecedent of “bro” culture. In recent biographical works about Roberto Bolaño—the documentary by Richard House, La batalla futura, and Monica Maristain’s book, a mixture of biography and oral history, El hijo de Míster Playa—Paloma Díaz has emerged as an important person in his youth. Born in Chile in 1953, Bolaño had moved with his parents to the DF in early adolescence. He met Paloma in 1976. Bolaño dedicated his poem Olor a plástico quemado, “The Smell of Burned Plastic,” to her: “Y las llamas escribirían tu nombre en el estómago del las nubes/ Palomita roja.”3 She told Monica Maristain, “He read it to me in his room and I almost died of embarrassment. I was eighteen or nineteen and nobody had ever dedicated a poem to me in my life. It made me nervous because I felt, frankly, that he was coming on to me, but I liked the poem.” They shared a brother and sister love “that rarely exists between true siblings,” Bolaño wrote in one of the long letters he mailed to her after he moved, in 1977, to Spain, where she visited him several times. Paloma never mentioned Bolaño to me, never said anything such as, “I have this other writer friend.” That could have simply been discretion, but I suspect it also reveals how little even some of those who’d been closest to Bolaño in Mexico expected of him then, in the early 1990s, when he was living in obscurity though only a few years from becoming the most deservedly celebrated Spanish-language writer in generations. The book that established Bolaño’s fame, of course, was The Savage Detectives, published in 1997, at its core a garrulous multivoiced channeling of his youth and friendships in the DF. That year, 1992, when I met Paloma and her friends, Bolaño was also only eleven years from his own premature death, at age fifty. María Guerra, a brilliant and influential young independent art curator with a lashing wit; the shy and gentle artist Marío Rangel; and Luis Lesur, a handsome, languid young man who became a professional astrologer, were among the friends who used to gather on that bed on those afternoons, and now they are dead too—María and Marío of cancer, Luis a suicide. Too many people die young in Mexico City. People were always breaking off their friendships with María because they couldn’t withstand her often hilariously cutting and inevitably penetrating remarks, and I, who received my share, and a few other friends who also loved her, scorned those people as defensive wimps. María had a freckled, impish face, wore her dark curls in a sort of poodle hairdo, and had a raucous laugh. Her empathetic sense of the painful human comedy, mixed with a disdain for self-pity and for complacency, was expressed as a hectoring, teasing belief in her friends’ capacity to rally and do better. People were always going to her for advice. I remember an afternoon in 1999, after she had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, when I phoned her at the hospital to arrange a visit and she answered weeping. She said, her voice overwrought but also characteristically buoyant, “Oh, Frank, I’m sorry, I can’t really talk right now, I’ve just been given terrible news,” and only a few days later she died, in her own bed in her apartment on Avenida Amsterdam, cared for by her twin sister, Ana. Now, thirteen years later, around the anniversary of her death, I’ve noticed how a few people still leave flower bouquets on the sidewalk beneath what used to be her window.

Through María I met Pia Elizondo, her husband, Gonzalo García, and Jaime Navarro, all still among my closest friends. Pia, a photographer, and Gonzalo—a painter, graphic designer, and editor and independent publisher—now live in Paris most of the year but come to Mexico every summer with their three children, in part to spend time with elderly parents and family. Both are the offspring of famous writers, Gonzalo of Gabriel García Márquez and Pia of the major Mexican avant-garde writer the late Salvador Elizondo. After that long night in the hospital when I wasn’t allowed into the emergency ward to speak to Aura, within an hour after Aura died late the next morning, Pia was the first person to arrive at my side. In Mexico City, funerals occur within twenty-four hours of a person’s death, the services usually held at a funeral home, often at one or another of the Gayosso establishments. The casket is usually on display, and people gather there, coming and going throughout the day, until finally, in late afternoon, the casket is taken to the cemetery, or the corpse is cremated. When I found Pia, now in her forties, in the summer of 2010, at the funeral of my good friend the artist Phil Kelly, an alcoholic Irishman who became a Mexican citizen, she said, “Well, here we are again. It seems like these are the only occasions where we get to see all our friends.”

After Tina and I broke up in 1995, she stayed in our Brooklyn apartment, and I moved to Mexico City, and ever since, I’ve never been away for more than a few months at a time. I hadn’t much liked Coyoacán—didn’t like its beautiful but too quiet, melancholy, high-walled streets; its aura of hippie nostalgia; its complacent culture of millionaire Communists; the relative lack of raffish cantinas and bars; and its prominence on the tourist circuit—the museum-homes of Frida Kahlo and Trotsky are there. The Condesa, its exuberant transformation into a new kind of Mexico City neighborhood—a sort of Mexican version of early Soho, or Williamsburg—under way just as I was coming off of a broken seven-year relationship, was much more to my liking. My first apartment, on Juan Escutia, a streaming thoroughfare that channels traffic off the Circuito Interior across a flank of the Condesa, was on the rooftop and consisted of two unconnected rooms: the bedroom and the kitchen. There was no roof over the space between the rooms, so that when it rained I couldn’t go from one to the other without getting wet, and when the rains were heavy, puddles spread inside from the doors, gradually swamping the floors. To reach my home, I came in through a gate off Juan Escutia, down an alley, through the kitchen of a ground- floor apartment rented by a scruffy Japanese couple and out its back door into a small courtyard where a narrow steel spiral staircase, like one on an old freighter, led up past four or five stories to the roof. Mexico City, at an altitude of 7,940 feet, mostly a vast level basin until it climbs the distant valley slopes, always feels close to the sky. My rooftop, higher than most of those around me, looked out on a cubist reef of flat rooftops of varying heights, water tanks, gardens, weather-raked potted trees, hung laundry, complicated and tangled electrical riggings, wooden or cinder-block shacks at complete odds with the architecture of the buildings they’re perched atop. (The beloved Mexico City writer Carlos Monsivais, in an essay listing the city’s essential images, called the flat rooftops “the continuation of agrarian life by other means, the natural extension of the farm. . . . Evocations and needs are concentrated on the rooftops.”) The wide sky overhead can seem like an element we’re deeply submerged in, one that overflows the mountains rimming the horizon as if these were the walls of an extinct volcano’s vast crater, inside of which has arisen a city. Mexico City’s skies are always dramatic, sometimes soaring and azure, with long rows of choreographed white clouds, moving slowly or swiftly; sometimes the clouds seem almost as near and suggestively sculptured as they do from an airplane; or the sky feels leaden and suffocating, or low and churning, or densely black and menacing, billowing in from one horizon as if poured into water from a giant bottle of ink, as a storm approaches and the winds pick up. The city’s pollution-abetted sunsets are spectacular conflagrations, blazing up over the western mountains, filling the sky with balloon dye colors, igniting the glassy modern office buildings that I can see out my rear windows into giant neon rectangles of scarlet. The night sky, sponging up light from the city below, is starless blackish phosphorescence, in which low clouds drift like mesoglea. When the moon is out in late afternoon it looms low over streets and buildings, enormous and pale yellow in the softer blue sky, like a ghostly school bus coming right at us.