9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

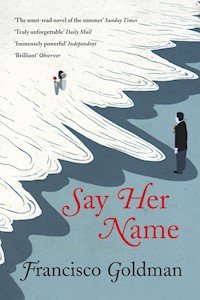

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Celebrated novelist Francisco Goldman married a beautiful young writer named Aura Estrada in a romantic Mexican hacienda in the summer 2005. The month before their second anniversary, during a long-awaited holiday, Aura broke her neck while body surfing. Francisco, blamed for Aura's death by her family and blaming himself, wanted to die, too. But instead he wrote Say Her Name, a novel chronicling his great love and unspeakable loss, tracking the stages of grief when pure love gives way to bottomless pain. Suddenly a widower, Goldman collects everything he can about his wife, hungry to keep Aura alive with every memory. From her childhood and university days in Mexico City with her fiercely devoted mother to her studies at Columbia University, through their newlywed years in New York City and travels to Mexico and Europe-and always through the prism of her gifted writings-Goldman seeks her essence and grieves her loss. Humor leavens the pain as he lives through the madness of utter grief and creates a living portrait of a love as joyous and playful as it is deep and profound. Say Her Name is a love story, a bold inquiry into destiny and accountability, and a tribute to Aura-who she was and who she would have been.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Praise for Say Her Name

‘A beautiful act of remembrance, love, and understanding. An essential, unforgettable love story and a living testament to an extraordinary woman.’—Gary Shteyngart

‘The madness of love, of death, of loss, of literature—Say Her Name is madness knit up into magnificence. We can only suspect that Francisco Goldman is an alchemist, or a magician, or a Faust, or a Job, or all of these things, for with no breathing equipment, he has mined a pearl from the ocean’s darkest depths. This book is fabulous in every sense of the word.’—Rivka Galchen

‘Say Her Name must be the only book about love ever written. It’s certainly the only one I’ll ever need to read. Francisco Goldman has alchemised grief into joy, death into life, and the act of reading into one of resurrection. His book is a miracle.’—Susan Choi

‘Francisco Goldman tells us that in “descending into memory like Orpheus” he hopes he might “bring Aura out alive for a moment.” But in the act of writing, Goldman transcends the contraints of myth, and achieves nothing short of the impossible. Page by page, by the breath of his own words, Say Her Name restores Aura from shade to flesh, and returns her, unforgettably and permanently, to our world.’—Jhumpa Lahiri

‘It doesn’t matter what’s “truth” and what’s “fiction,” for the story is inherently moving and tragic, and it focuses on loss and lament—universal themes whether they derive from memoir or from an author’s imagination . . . Appropriately, in this novel of death and dying, Goldman writes gorgeous, heartbreaking prose.’—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

‘The feeling, the memorial incarnation that this book creates, is monumental. Essential . . . This book about tragic death is a gift for the living.’—Library Journal, starred review

‘There is beautiful writing in this book—beautiful, perceptive descriptions of places, beautifully turned assaults on the citadel of loss, on the firmament of love and passion, indelible glimpses of the self as bedlam. And thank goodness it’s so, because it is such a sad story that only beauty could possibly redeem it.’—Richard Ford

‘Enrapturing . . . Vivid . . . Goldman has entwined fact and fiction in his previous novels, but never so daringly or so poignantly. . . . Tender, candid, sorrowful, and funny, this ravishing novel embodies the relentless power of the sea, as hearts are exposed like a beach at low tide only to be battered by a resurgent, obliterating force, like the wave that claims Aura’s life on the Oaxaca coast. Out of crushing loss and despair, Goldman has forged a radiant and transcendent masterpiece.’—Booklist, starred review

Say Her Name

Award-winning writer Francisco Goldman is the author of three novels, The Divine Husband, The Long Night of White Chickens and The Ordinary Seaman, and one work of non-fiction, The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? Goldman has been a contributing editor for Harper’s magazine and his fiction, journalism and essays have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Esquire and The New York Times Magazine. He currently directs the Premio Auro Estrada/Aura Estrada Prize and lives in Brooklyn and Mexico City.

ALSO BY FRANCISCO GOLDMANThe Art of Political MurderThe Divine HusbandThe Ordinary SeamanThe Long Night of White Chickens

Say Her Name

Francisco Goldman

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in the United States of America in 2011 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © Francisco Goldman, 2011

For their support during the writing of this book, my gratitude to the American Academy of Berlin and the von der Heyden Family Foundation; the Ucross Foundation; and Beatrice Monti and the Santa Maddalenna Foundation. Also my deepest thanks to N.G. in Mexico City and K.R. in New York—you helped me through the worst of it.—F. G.

The moral right of Francisco Goldman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

“If You Find Yourself Caught In Love,” written by Bob Kildea, Christopher Geddes, Michael Cooke, Richard Colburn, Sarah Martin, Stephen Jackson, and Stuart Murdoch. Copyright © 2003 Sony/ATV Music Publishing UK Limited. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

“Little Red Cap” from the book The World’s Wife by Carol Ann Duffy. Copyright © 1999 by Carol Ann Duffy. Originally published by Picador, an imprint Pan Macmillan, London. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

“Stephanie Says,” written by Lou Reed. Copyright © Metal Machine Music. US and Canadian Rights for Metal Machine Music controlled and administered by Spirit One Music (BMI). World excluding US and Canadian Rights controlled and administered by EMI Music Publishing, Ltd. International Copyright Secured. Used by Permission. All Rights Reserved.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 602 6 Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 598 2

Printed in Great Britian by

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

E-book ISBN: 978-1-6118-5997-3

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Vladimir: Suppose we repented . . . Estragon: Our being born?

—Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett

It isn’t simply death—it’s always the death of someone.

—Serge Leclaire

Dear Losse! since thy untimely fate My task hath beene to meditate On Thee, on Thee; Thou art the Book, The Library whereon I look, Though almost blind.

—“Exequy on his Wife,” Henry King, Bishop of Chichester

I wouldn’t want to be faster or greener than now if you were with me O you were the best of all my days

—“Animals,” Frank O’Hara

. . . and perhaps you will find out when you go to heaven, after your gig with the Shanghai Bureau. And perhaps you will find your bear costume in a closet in heaven.

—“My Shanghai Days,” Aura Estrada

Say Her Name

1

Aura died on July 25, 2007. I went back to Mexico for the first anniversary because I wanted to be where it had happened, at that beach on the Pacific coast. Now, for the second time in a year, I’d come home again to Brooklyn without her.

Three months before she died, April 24, Aura had turned thirty. We’d been married twenty-six days shy of two years.

Aura’s mother and uncle accused me of being responsible for her death. It’s not as if I consider myself not guilty. If I were Juanita, I know I would have wanted to put me in prison, too. Though not for the reasons she and her brother gave.

From now on, if you have anything to say to me, put it in writing—that’s what Leopoldo, Aura’s uncle, said on the telephone when he told me that he was acting as Aura’s mother’s attorney in the case against me. We haven’t spoken since.

Aura.

Aura and me

Aura and her mother

Her mother and me

A love-hate triangle, or, I don’t know

Mi amor, is this really happening?

Où sont les axolotls?

Whenever Aura took leave of her mother, whether at the Mexico City airport or if she was just leaving her mother’s apartment at night, or even when they were parting after a meal in a restaurant, her mother would lift her hand to make the sign of the cross over her and whisper a little prayer asking the Virgin of Guadalupe to protect her daughter.

Axolotls are a species of salamander that never metamorphose out of the larval state, something like pollywogs that never become frogs. They used to be abundant in the lakes around the ancient city of Mexico, and were a favorite food of the Aztecs. Until recently, axolotls were said to be still living in the brackish canals of Xochimilco; in reality they’re practically extinct even there. They survive in aquariums, laboratories, and zoos.

Aura loved the Julio Cortázar short story about a man who becomes so mesmerized by the axolotls in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris that he turns into an axolotl. Every day, sometimes even three times a day, the nameless man in that story visits the Jardin des Plantes to stare at the strange little animals in their cramped aquarium, at their translucent milky bodies and delicate lizard’s tails, their pink flat triangular Aztec faces and tiny feet with nearly human-like fingers, the odd reddish sprigs that sprout from their gills, the golden glow of their eyes, the way they hardly ever move, only now and then twitching their gills, or abruptly swimming with a single undulation of their bodies. They seem so alien that he becomes convinced they’re not just animals, that they bear some mysterious relation to him, are mutely enslaved inside their bodies yet somehow, with their pulsing golden eyes, are begging him to save them. One day the man is staring at the axolotls as usual, his face close to the outside of the tank, but in the middle of that same sentence, the “I” is now on the inside of the tank, staring through the glass at the man, the transition happens just like that. The story ends with the axolotl hoping that he’s succeeded in communicating something to the man, in bridging their silent solitudes, and that the reason the man no longer visits the aquarium is because he’s off somewhere writing a story about what it is to be an axolotl.

The first time Aura and I went to Paris together, about five months after she’d moved in with me, she wanted to go to the Jardin des Plantes to see Cortázar’s axolotls more than she wanted to do anything else. She’d been to Paris before, but had only recently discovered Cortázar’s story. You would have thought that the only reason we’d flown to Paris was to see the axolotls, though actually Aura had an interview at the Sorbonne, because she was considering transferring from Columbia. Our very first afternoon, we went to the Jardin des Plantes, and paid to enter its small nineteenth-century zoo. In front of the entrance to the amphibian house, or vivarium, there was a mounted poster with information in French about amphibians and endangered species, illustrated with an image of a red-gilled axolotl in profile, its happy extraterrestrial’s face and albino monkey arms and hands. Inside, the tanks ran in a row around the room, smallish illuminated rectangles set into the wall, each framing a somewhat different humid habitat: moss, ferns, rocks, tree branches, pools of water. We went from tank to tank, reading the placards: various species of salamanders, newts, frogs, but no axolotls. We circled the room again, in case we’d somehow missed them. Finally Aura went up to the guard, a middle-aged man in uniform, and asked where the axolotls were. He didn’t know anything about the axolotls, but something in Aura’s expression seemed to give him pause, and he asked her to wait; he left the room and a moment later came back with a woman, somewhat younger than him, wearing a blue lab coat. She and Aura spoke quietly, in French, so I couldn’t understand what they were saying, but the woman’s expression was lively and kind. When we went outside, Aura stood there for a moment with a quietly stunned expression. Then she told me that the woman remembered the axolotls; she’d even said that she missed them. But they’d been taken away a few years before and were now in some university laboratory. Aura was in her charcoal gray woolen coat, a whitish wool scarf wrapped around her neck, strands of her straight black hair mussed around her soft round cheeks, which were flushed as if burning with cold, though it wasn’t particularly cold. Tears, just a few, not a flood, warm salty tears overflowed from Aura’s brimming eyes and slid down her cheeks.

Who cries over something like that? I remember thinking. I kissed the tears, breathing in that briny Aura warmth. Whatever it was that so got to Aura about the axolotls not being there seemed part of the same mystery that the axolotl at the end of Cortázar’s story hopes the man will reveal by writing a story. I always wished that I could know what it was like to be Aura.

Où sont les axolotls? she wrote in her notebook. Where are they?

Aura moved in with me in Brooklyn about six weeks after she’d arrived in New York from Mexico City with her multiple scholarships, including a Fulbright and another from the Mexican government, to begin studying for a PhD in Spanish-language literature at Columbia. We lived together almost four years. At Columbia she shared her university housing with another foreign student, a Korean girl, a botanist of some highly specialized kind. I saw that apartment only two or three times before I moved Aura’s things to my place. It was a railroad flat, with a long narrow hallway, two bedrooms, a living room at the front. A student apartment, filled with student things: her Ikea bookcase, a set of charcoal-hued nonstick pots and pans and utensils, a red beanbag chair, a stereo unit, a small toolbox, from Ikea too, still sealed in its clear plastic wrapper. Her mattress on the floor, clothing heaped all over it. That apartment made me feel nostalgic as hell—for college days, youth. I was dying to make love to her then and there, in the sumptuous mess of that bed, but she was nervous about her roommate coming in, so we didn’t.

I took her away from that apartment, leaving her roommate, whom Aura got along with fine, on her own. But a month or so later, once she felt sure that she was going to stay with me, Aura found another student to take her share, a Russian girl who seemed like someone the Korean girl would like.

Up there, on Amsterdam Avenue and 119th Street, Aura lived at the edge of campus. In Brooklyn, she had to ride the subway at least one hour each way to get to Columbia, usually during rush hour, and she went almost every day. She could take the F train, transfer at Fourteenth Street and make her way through a maze of stairways and long tunnels, grim and freezing in winter, to the 2 and 3 express trains, and switch to the local at Ninety-sixth Street. Or she could walk twenty-five minutes from our apartment to Borough Hall and catch the 2 or 3 there. Eventually she decided she preferred the second option, and that was what she did almost every day. In winter the trek could be brutally cold, especially in the thin wool coats she wore, until finally I convinced her to let me buy her one of those hooded North Face down coats, swaddling her from the top of the head to below the knees in goose down–puffed blue nylon. No, mi amor, it doesn’t make you look fat, not you in particular, everybody looks like a walking sleeping bag in one of those, and who cares anyway? Isn’t it better to be snug and warm? When she wore the coat with the hood up, collar closed under her chin, with her gleaming black eyes, she looked like a little Iroquois girl walking around inside her own papoose, and she hardly ever went out into the cold without it.

Another complication of the long commute was that she regularly got lost. She’d absentmindedly miss her stop or else take the train in the wrong direction and, engrossed in her book, her thoughts, her iPod, wouldn’t notice until she was deep into Brooklyn. Then she’d call from a pay phone in some subway station I’d never heard of, Hola, mi amor, well, here I am in the Beverly Road Station, I went the wrong way again—her voice determinedly matter-of-fact, no big deal, just another overscheduled New Yorker coping with a routine dilemma of city life, but sounding a touch defeated anyhow. She didn’t like being teased about going the wrong way on the subway, or getting lost even when she was walking in our own neighborhood, but sometimes I couldn’t help it.

From Aura’s first day in our Brooklyn apartment to nearly her last, I walked her to the subway stop every morning—except on those mornings when she rode her bicycle to Borough Hall and left it locked there, though that routine didn’t last long because the homeless drunks and junkies of downtown Brooklyn kept stealing her bike seat, or when it was raining or when she was just running so behind that she took a taxi to Borough Hall, or on the rare occasion when she flew out the door like a furious little tornado because it was getting late and I was still stuck on the can yelling for her to wait, and the two or three times when she was just so pissed off at me about something or other that she absolutely didn’t want me to walk with her.

Usually though, I walked her to the F train stop on Bergen, or I walked her to Borough Hall, though eventually we agreed that when she was headed to Borough Hall I would go only as far as the French guy’s deli on Verandah Place—I had work to do and couldn’t just lose nearly an hour every day going to the station and back—though she would try to coax me farther, to Atlantic Avenue, or to Borough Hall after all, or even up to Columbia. Then I’d spend the day in Butler Library—a few semesters previous I’d taught a writing workshop at Columbia and I still had my ID card—reading or writing or trying to write in a notebook, or I’d sit at one of the library computers checking e-mail or killing time with online newspapers, routinely starting with the Boston Globe sports section (I grew up in Boston). Usually we’d have lunch at Ollie’s, then go and blow money on DVDs and CDs at Kim’s, or browse in Labyrinth Books, coming out carrying heavy bags of books neither of us had the extra time to read. On days when she hadn’t convinced me to accompany her to Columbia in the morning, she’d sometimes phone and ask me to come all the way up there just to have lunch with her, and as often as not, I’d go. Aura would say,

Francisco, I didn’t get married to eat lunch by myself. I didn’t get married to spend time by myself.

On those morning walks to the subway, Aura always did most or even all of the talking, about her classes, professors, other students, about some new idea for a short story or novel, or about her mother. Even when she was being especially neuras, going on about her regular anxieties, I’d try to come up with new encouragements or else rephrase or repeat prior ones. But I especially loved it when she was in the mood to stop every few steps and kiss and nip at my lips like a baby tiger, and her mimed silent laughter after my ouch, and the way she’d complain, ¿Ya no me quieres, verdad? if I wasn’t holding her hand or didn’t have my arm around her the instant she wanted me to. I loved our ritual except when I didn’t really love it, when I’d worry, How am I ever going to get another damned book written with this woman who makes me walk her to the subway every morning and cajoles me into coming up to Columbia to have lunch with her?

I still regularly imagine that Aura is beside me on the sidewalk. Sometimes I imagine I’m holding her hand, and walk with my arm held out by my side a little. Nobody is surprised to see people talking to themselves in the street anymore, assuming that they must be speaking into some Bluetooth device. But people do stare when they notice that your eyes are red and wet, your lips twisted into a sobbing grimace. I wonder what they think they are seeing and what they imagine has caused the weeping. On the surface, a window has briefly, alarmingly, opened.

One day that first fall after Aura’s death, in Brooklyn, on the corner of Smith and Union, I noticed an old lady standing on the opposite corner, waiting to cross the street, a normal-looking old lady from the neighborhood, neat gray hair, a little hunched, a sweet jowly expression on her pale face, looking as if she were enjoying the sunlight and October weather as she waited patiently for the light to change. The thought was like a silent bomb: Aura will never find out about being old, she’ll never get to look back on her own long life. That was all it took, thinking about the unfairness of that and about the lovely and accomplished old lady Aura had surely been destined to become.

Destined. Was I destined to have come into Aura’s life when I did, or did I intrude where I didn’t belong and disrupt its predestined path? Was Aura supposed to have married someone else, maybe some other Columbia student, that guy studying a few seats away from her in Butler Library or the one in the Hungarian Pastry Shop who couldn’t stop shyly peeking at her? How can anything other than what happened be accurately described as destined? What about her own free will, her own responsibility for her choices? When the light changed and I crossed Smith Street, did that old lady notice my face as we passed? I don’t know. My blurred gaze was fixed on the pavement and I wanted to be back inside our apartment. Aura was more present there than she was anywhere else.

The apartment, which I’d been renting for eight years by then, was the parlor floor of a four-story brownstone. Back when the Rizzitanos, the Italian family that still owned the building, used to live there, occupying all four floors, the parlor would have been their living room. But it was our bedroom. It had such tall ceilings that to change a lightbulb in the hanging lamp I’d climb a five-foot stepladder, stand on tiptoes atop its rickety pinnacle and reach up as high as I could, though still end up bent over, arms flapping, fighting for balance—Aura, watching from her desk in the corner, said, You look like an amateur bird. Around the tops of the walls ran a plaster cornice, whitewashed like the walls, a neoclassical row of repeating rosettes atop a wider one of curled fronds. Two long windows, with deep sills and curtains, faced the street, and between the windows, rising from floor to ceiling like a chimney, was the apartment’s gaudiest feature: an immense mirror in a baroque, gold-painted wooden frame. Now Aura’s wedding dress partly covered the mirror, hung from a clothes hanger and butcher twine that I’d tied around gilded curlicues on opposite sides at the top. And on the marble shelf at the foot of the mirror was an altar made up of some of Aura’s belongings.

When I came back from Mexico that first time, six weeks after Aura’s death, Valentina, who studied with Aura at Columbia, and their friend Adele Ramírez, who was visiting from Mexico and staying with Valentina, came to pick me up at Newark Airport in Valentina’s investment-banker husband’s BMW station wagon. I had five suitcases: two of my own and three filled with Aura’s things, not just her clothes—I’d refused to throw or give away almost anything of hers—but also some of her books and photos, and a short lifetime’s worth of her diaries, notebooks, and loose papers. I’m sure that if that day some of my guy friends had come for me at the airport instead, and we’d walked into our apartment, it would have been much different, probably we would have taken a disbelieving look around and said, Let’s go to a bar. But I’d hardly finished bringing in the suitcases before Valentina and Adele went to work building the altar. They dashed around the apartment as if they knew where everything was better than I did, choosing and carrying treasures back, occasionally asking for my opinion or suggestion. Adele, a visual artist, crouched over the marble shelf at the foot of the mirror, arranging: the denim hat with a cloth flower stitched onto it that Aura bought during our trip to Hong Kong; the green canvas satchel she brought to the beach that last day, with everything inside it just as she’d left it, her wallet, her sunglasses, and the two slender books she was reading (Bruno Schulz and Silvina Ocampo); her hairbrush, long strands of black hair snagged in the bristles; the cardboard tube of Chinese pick-up sticks she bought in the mall near our apartment in Mexico City and took into the T.G.I. Fridays there, where we sat drinking tequila and playing pick-up sticks two weeks before she died; a copy of the Boston Review, where her last published essay in English had appeared early that last summer; her favorite (and only) pair of Marc Jacobs shoes; her little turquoise drinking flask; a few other trinkets, souvenirs, adornments; photographs; candles; and standing empty on the floor at the foot of the altar, her shiny mod black-and-white-striped rubber rain boots with the hot pink soles. Valentina, standing before the towering mirror, announced: I know! Where’s Aura’s wedding dress? I went and got the wedding dress out of the closet, and the stepladder.

It was just the kind of thing Aura and I made fun of: a folkloric Mexican altar in a grad student’s apartment as a manifestation of corny identity politics. But it felt like the right thing to do now, and throughout that first year of Aura’s death and after, the wedding dress remained. I regularly bought flowers to put in the vase on the floor, and lit candles, and bought new candles to replace the burned-out ones.

The wedding dress was made for Aura by a Mexican fashion designer who owned a boutique on Smith Street. We’d become friendly with the owner, Zoila, who was originally from Mexicali. In her store we’d talk about the authentic taco stand we were going to open someday to make money off the drunk, hungry, young people pouring out of the Smith Street bars at night, all three of us pretending that we were really serious about joining in this promising business venture. Then Aura discovered that Zoila’s custom-tailored bridal dresses were recommended on the Web site Daily Candy as a thrifty alternative to the likes of Vera Wang. Aura went to Zoila’s studio, in a loft in downtown Brooklyn, for three or four fittings, and she came home from each feeling more anxious than before. She was, at first, after she went to pick up the finished dress, disappointed in it, finding it more simple than she’d imagined it was going to be, and not much different from some of the ordinary dresses Zoila sold in her store for a quarter of the price. It was an almost minimalist version of a Mexican country girl’s dress, made of fine white cotton, with simple embellishments of silk and lace embroidery, and it widened into ruffles at the bottom.

But in the end, Aura decided that she liked the dress. Maybe it just needed to be in its rightful habitat, the near-desert setting of the Catholic shrine village of Atotonilco, amid an old mission church and cactus and scrub and the green oasis grounds of the restored hacienda that we’d rented for the wedding, beneath the vivid blue and then yellow-gray immensity of the Mexican sky and the turbulent cloud herds coming and going across it. Maybe that was the genius of Zoila’s design for Aura’s dress. A sort of freeze-dried dress, seemingly plain as tissue paper, that shimmered to life in the charged thin air of the high plains of central Mexico. A perfect dress for a Mexican country wedding in August, a girlhood dream of a wedding dress after all. Now the dress was slightly yellowed, the shoulder straps darkened by salty perspiration, and one of the bands of lace running around the dress lower down, above where it widened out, was partly ripped from the fabric, a tear like a bullet hole, and the hem was discolored and torn from having been dragged through mud and danced on and stepped on during the long night into dawn of our wedding party, when Aura had taken off her wedding shoes and slipped into the dancing shoes we’d bought at a bridal shop in Mexico City, which were like a cross between white nurse shoes and seventies disco platform sneakers. A delicate relic, that wedding dress. At night, backed by the mirror’s illusion of depth and the reflected glow of candles and lamps, the baroque frame like a golden corona around it, the dress looks like it’s floating.

* * *

Despite the altar, or maybe partly because of it, our cleaning lady quit. Flor, from Oaxaca, now raising three children in Spanish Harlem, who came to clean once every two weeks, said it made her too sad to be in our apartment. The one time Flor did come, I watched her kneel to pray at the altar, watched her pick up photographs of Aura and press them to her lips, smudging them with her emphatic kisses and tears. She imitated Aura’s reliable words of praise for her work, the happy pitch of her voice: Oh Flor, it’s as if you work miracles! Ay, señor, said Flor. She was always so happy, so full of life, so young, so good, she always asked after my children. How could she do her job now, in that way that had always so pleased Aura, Flor pleadingly asked me, if she couldn’t stop crying? Then she’d taken her sadness and tears home with her, home to her children, she explained later when she phoned, and that wasn’t right, no señor, she couldn’t do it anymore, she was sorry but she had to quit. I didn’t bother to look for a new cleaning lady. I suppose I thought she would feel sorry for me and come back. I tried phoning, finally, to beg her to come back, and got a recorded message that the number was no longer in service. Then, months after she’d quit, incredibly, she repented and did phone and leave her new telephone number—apparently, she’d moved—on the answering machine. But when I phoned back, it was the wrong number. Probably I’d written it down wrong, I’m a touch dyslexic anyway.

Now, fifteen months after Aura’s death, coming home without her again—no one to meet me at the airport this time—I found the apartment exactly as I’d left it in July. The bed was unmade. The first thing I did was open all the windows, letting in the cool, damp October air.

Aura’s MacBook was still there, on her desk. I’d be able to pick up where I’d left off, working on, organizing, trying to piece together her stories, essays, poems, her just begun novel, and her unfinished writings, the thousands of fragments, really, that she left in her computer, in her labyrinthine and scattered manner of storing files and documents. I thought I felt ready to immerse myself in that task.

In the bedroom there were old dead rose petals, darker than blood, on the floor around the vase in front of the altar, but the vase was empty. In the kitchen, Aura’s plants, despite not having been watered in three months, were still alive. I stuck my finger in the soil of one pot and found it moist.

Then I remembered that I’d left a key with the upstairs neighbors, asking them to water Aura’s plants while I was away. I’d only intended to go to Mexico for the first anniversary and stay a month, but I’d stayed three, and they’d kept it up all that time. They’d thrown out the dead roses, which must have begun to rot and smell. And they’d collected my mail in a shopping bag that they had put next to the couch, just inside the apartment door.

On the beach we—I and some of the swimmers who saw or heard my cries for help—pulled Aura out of the water and set her down in the almost ditchlike incline gouged by the waves, and then we picked her up again and carried her to where it was level and laid her on the hot sand. As she fought for air, closing and opening her mouth, whispering only the word “aire” when she needed me to press my lips to hers again, Aura said something that I don’t actually remember hearing, just as I remember so little of what happened, but her cousin Fabiola, before she took off looking for an ambulance, heard it and later told me. What Aura said, one of the last things she ever said to me, was:

Quiéreme mucho, mi amor.

Love me a lot, my love.

No quiero morir. I don’t want to die. That may have been the last full sentence she ever spoke, maybe her very last words.

Did that sound self-exculpating? Is this the kind of statement I should prohibit myself from making? Sure, Aura’s plea and invocation of love would play well on any jury’s emotions and sympathies, but I’m not in a courtroom. I need to stand nakedly before the facts; there’s no way to fool this jury that I am facing. It all matters, and it’s all evidence.

2

Is this really happening, mi amor? Am I really back in Brooklyn again without you? Throughout your first year of death and now, out on the streets at night, pounding the pavement, up one side of the block, down the other, lingering at steamy windows looking at menus that I know by heart, what take-out food should I choose, what cheap restaurant should I eat in tonight, what bar will I stop into for a drink or two or three or five where I won’t feel so jarringly alone—but where don’t I feel jarringly alone?

The five or so years before I met Aura were the loneliest I’d ever known. The year plus months since her death were much lonelier. But what about the four years in between? Was I a different man than I was before those four years, an improved man, because of the love and happiness that I experienced? Because of what Aura gave to me? Or was I just the same old me who, for four years, was inexplicably lucky? Four years—are those too few years to hold such significance in a grown man’s life? Or can four years mean so much that they will forever outweigh all the others put together?

After she died, for the first month or so, I didn’t dream about Aura, though in Mexico City I felt her presence everywhere. Then, in the fall, when she should have been starting her classes, I had my first dream, one in which it was urgent that I buy a cell phone. In the middle of a lush green field with a silvery stream running through it, I found a wooden hut that was a cell phone store, and I went inside. I was desperate to phone Wendy, another classmate and friend of Aura’s. I wanted to ask Wendy if Aura missed me. I wanted to ask Wendy, in these exact words, Does she miss our domestic routines? I carried the new cell phone, silvery with sapphire keys, out of the hut, into the field, toward the stream, but I couldn’t get it to work. Frustrated, I hurled the phone away.

Do you miss our domestic routines, mi amor?

Can this really be happening to us?

Degraw Street, where we lived, supposedly marks the border between Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill. Our apartment was on the Carroll Gardens side of the street, Cobble Hill on the other side. When I first moved there, about four years before I met Aura, Carroll Gardens still seemed like the classic Brooklyn Italian neighborhood, old-fashioned Italian restaurants where mobsters and politicians used to eat, lawn statues of the Virgin, old men playing bocce ball in the playground; especially on summer nights, with so many loud tough-guy types milling around, I’d always feel a little menaced walking through there. Cobble Hill was where Winston Churchill’s mother was born and still looked the part, with its landmark Episcopalian church that had a Tiffany interior, quaint carriage house mews, and park. Both neighborhoods had pretty much blended together now, overtaken mostly by prosperous young white people. 9/11 had accelerated the process—nice and quiet, family-seeming neighborhood across the Brooklyn Bridge. Now, by day, you wove through long crooked trains of baby carriages on the Court Street sidewalks, and ate lunch or went for coffee in places filled with young moms, au pairs, and an embarrassing number of writers. The Italian men’s social clubs had become hipster cocktail bars. On every street brownstones converted into apartments years ago were being renovated back into single-family homes. A few blocks away, just across the BQE is Red Hook, the harbor and port; at night you can hear ships’ foghorns, Aura loved that; with a swimmer’s little wriggle she’d nestle closer in bed and hold still, as if the long mournful blasts were about to float past us like manta rays in the dark.

This was Aura’s yoga studio; here’s the spa she’d go to for a massage when she was stressed; here was her favorite clothing boutique, and there, her second favorite; our fish store; this is where she bought those cool eyeglasses with yellow-tinted lenses; our late-night burger and drinks place; our brunch place; “the-restaurant-we-always-fight-in”—that’s what walking these streets had become now, a silent chanting of the stations. The neighborhood has an abundance of Italian pizza parlors and brick-oven places, and a single small antiseptic Domino’s Pizza on the corner of Smith and Bergen, by the subway exit, its customers mostly residents of the Hoyt Street housing projects and black and Latino teenagers from a nearby high school. One night we were coming home late from drinking with friends when, without saying anything, Aura darted through the Domino’s glass doors and stood at the counter no more than a minute, I swear, before she came back out with a giant pizza box in her hands and a look-what-I-just-won grin. All the upscale pizza places were closed by that hour, but I bet at that moment none could have satisfied Aura’s hungry impulse like Domino’s. Where she grew up in Mexico City, amid the residential complexes of the city’s south, every evening an army of helmeted delivery boys on motorbikes, thousands upon thousands, buzzed and zoomed like bees through the clogged expressways and streets, speeding fast food pizza to the apartments and families of working and single mothers like Aura’s. Now I never walk past that Domino’s without seeing her coming out the door with the pizza and that smile.

The long-defunct mud-hued Catholic church across the street from our apartment was being converted into a condo building (the developers, Orthodox Jews, and the work crew, Mexican); Aura would have been happy about the new Trader Joe’s down at Atlantic and Court; on Smith Street, the taco place we were going to open with Zoila opened but Zoila’s boutique closed last year and I still don’t know where she’s gone to. Around the corner is the grungy but popular Wi-Fi café that Aura often liked to study and work in when she wasn’t up at Columbia. She found it easier to concentrate there than at home. No me bugging her for attention or sex or noisily typing away in the next room, no mother phoning from Mexico. I’d come in and see her sitting at one of the tables against the brick wall, half-eaten bagel atop its wax-paper bag, mug of coffee, hair pushed back by a barrette or a red band or tied back to keep it out of her face as she leaned over her laptop, headphones on, that determined, locked-in look, lightly biting her lower lip, and I’d stand and watch her or pretend I’d never seen her before and wait for her to lift her eyes and see me. I used to come to this café to work, too. She didn’t mind. We’d share a table, have lunch or split a bagel or a cookie. Now I only come in for morning take-out coffee. Waiting in the inevitable line, I stare at the row of tables, the long blue bench against the wall, strangers sitting there with their computers.

I hadn’t thrown away or moved out any of Aura’s clothes, they were still in her chest of drawers and in the walk-in closet. Her cold weather coats and jackets, including the down one, hung from a peg by the front door. At least once a day I’d open a drawer and hold a pile of her clothes to my nose, frustrated that they smelled more of the drawer’s wood than of Aura, and sometimes I emptied out a drawer on the bed and lay facedown in her clothes. I knew that eventually I should give these things away—her clothes, at least—that there was somebody out there who could not afford a down coat and whose life would be made more bearable by it, maybe even saved. I pictured an illegal immigrant woman or girl in some brutally cold place, a meatpacking plant town in Wisconsin, a Chicago tenement without heat. But I wasn’t ready to let go of anything. It wasn’t even an argument I had with myself—though I did discuss it with some of Aura’s friends. At first they had seemed fixated on the idea that, for my own good, I needed to get rid of some of her things. Nobody suggested I had to get rid of everything. Why couldn’t I do it a little at a time, donate some of her coats to the city’s winter coat drive, for starters? In the end, of course, I should keep a few special things, such as her wedding dress, “to remember her by.” During those first months, I drifted away from most of my male friends and shut myself off from my family—my mother and siblings—and only wanted to be around women: Aura’s friends but also a few women I’d been close to since long before Aura.

With the exception of the table that I wrote at in the corner of the middle room—the one between the kitchen and the parlor room where we slept—and some of the old bookshelves, Aura and I had slowly gotten rid of and replaced all the furniture from my slovenly bachelor years. It frustrated Aura that we hadn’t moved into a new apartment, free of traces and reminders of my past without her, a place she could make wholly ours, though she did completely transform the apartment we had. Sometimes I’d come home and find her pushing even the heaviest furniture around, changing the crowded layout in a way that had never occurred to me or even seemed possible, as if the apartment were some kind of complicated puzzle that could only be solved by pushing furniture around and that she’d become obsessed with, or else maybe it could never be solved, but she always made the place look better.

The last piece of furniture we bought, at a secondhand store about five blocks away, was a fifties-style kitchen table, its inlaid Formica top patterned in cerulean blue and pearly white, cheery as a child’s painting of a sunny sky and clouds. In the kitchen, also, was the evergreen-painted kitchen hutch that we’d bought at an antique store in a small rural town in the Catskills during a weekend when we were visiting Valentina and Jim at their country house; about two months after we bought it, the store’s exasperated owner phoned—it wasn’t her first call—to tell us that if we didn’t come for the hutch soon, she’d put it up for sale again, no money back. That kitchen hutch was no bargain. Farmhouse hutches of just that kind could be found for the same price in our neighborhood antique stores and on Atlantic Avenue. But we rented an SUV in Brooklyn to go and fetch ours, and spent the weekend at a sort of Italian-American hunting lodge, a Plexiglas Jacuzzi with shiny brass fixtures and an artificial gas fireplace in our cabin, where we holed up with books, wine, a football game on TV with the sound off, laughing our heads off when we tried to fuck in the ridiculous Jacuzzi, and whenever we were hungry we’d go into the restaurant, which was decorated with several generations’ worth of autographed photos of New York Yankees, to dig back into the perpetual all-you-can-eat buffet, spaghetti with giant meatballs, sausage lasagna, and the like. In the end, that hutch ended up costing us about four times what we would have paid to buy one in Brooklyn.

In our kitchen, along with the hutch, were all our other culinary things—utensils, pots and pans—mostly untouched since last touched by Aura. Her Hello Kitty toaster that branded every piece of toast with the Hello Kitty logo—I did still use that toaster, smiling away at Aura’s girly nerdiness whenever I spread butter over the kitty face. The Cuisinart ice-cream maker Aura bought just so that she could make dulce de leche ice cream for her birthday party when she turned thirty, the ice-cream maker’s metallic freezing cylinder still sitting in the freezer. The long dining table from ABC Carpet and Home that we paid for with wedding gift money, and that with its extensions at both ends provided enough space for the twenty-plus friends who came to that party, sitting jammed in around it. We made cochinita pibil, soft pork oozing citrus-and-achiote spiced juices inside a wrapping of banana leaves roasted parchment dry, and rajas con crema, and arroz verde, and Valentina came early and prepared her meatballs in chipotle sauce in our kitchen, and there was a gorgeously garish birthday cake from a Mexican bakery in Sunset Park—white, orange, and pink frosting, fruit slices in a glazed ring on top—served with Aura’s ice cream. Her birthday present that year was two long rustic benches for seating at the table. She wanted us to have lots of dinner parties.

It isn’t true that to be happy in New York City you have to be rich. I’m not saying that another twenty, thirty, fifty grand a year wouldn’t have improved our circumstances and maybe made us even happier. But few people who’d known me or Aura before we got together would have guessed either of us had any talent for domestic life.

Aura’s three simultaneous scholarships added up to a startling salary, for a full-time student anyway. As I never asked her to pay rent, or for much of anything else, she’d had money to spend and to save. She’d wanted to use her savings to help us buy a house or an apartment one day, if I ever managed to save enough money of my own, which I was determined to do. When I finally went and closed Aura’s account, I was astonished at how much was there. Now I was pretty much living off those savings, money from the scholarships but also what she’d been saving since her adolescence. I’d already used up the insurance reimbursement money that was meant to pay off the credit cards I’d used for Aura’s medical, hospital, and ambulance bills in Mexico. I’d paid only about half of those charges, digging myself still deeper into debt. So I was in debt. And so what? Because I had only a part-time position in the English department at the small Connecticut college where I was teaching, I hadn’t been entitled to paid bereavement leave. But I couldn’t bear to teach that semester after Aura’s death, so I’d resigned. I knew that soon I would have to get a job. What kind of job? No idea. But I couldn’t see myself teaching again. I had my reasons. The enthusiasm and willed energy of a committed performer that somebody like me, not a trained literary scholar, is going to need to hold the attention of a classroom of easily bored twenty-year-olds, that was gone. In love with Aura, married, unabashedly happy, I’d been a good and entertaining literature clown.

The plants Aura had kept out on the fire escape had been dead since last winter and were now just plastic and clay pots filled with dirt and plant rubble, gray stems, and crinkly leaves. But her plastic folding chair was still out there, dirty-urban-weather-streaked but otherwise untouched by any human since the last time she sat in it, along with the glass ashtray at its foot, washed out by more than a year of rain. Sometimes squirrels jumped onto the seat from the fire escape’s railing, drank from the rain or melted snow pooled in its slight concavity. In nice weather Aura liked to sit out there on the fire escape, in that little rusted cage, feet propped on the stairs leading to the landing above, surrounded by her plants, reading, writing on her laptop, smoking a little. She wasn’t a heavy smoker. Some days she’d smoke a few cigarettes; other days, none. Occasionally, she smoked pot, usually when someone at school gave her some. I still had her last, almost empty, bag of pot in the drawer of our kitchen hutch. To Aura it was as if the fire escape was no less a garden than our downstairs neighbors’ actual backyard garden that she sat perched above. I’d tease her that she was like Kramer from the Seinfeld show who did things like that, celebrating the Fourth of July by setting a lawn chair in front of his apartment door, pretending the hallway was a backyard in the suburbs, and sitting there with beer, cigar, and a hot dog.

One morning I found myself standing in the kitchen looking through the window at the chair on the fire escape as if I’d never seen it before. That’s when I thought to name it Aura’s Journey Chair. I imagined her descending slowly down a long shaft of yellow-pink translucent light, in a sitting position, holding a book open in her hands, landing softly in the chair, returned from her long, mysterious journey. She glances up from her book, notices me watching through the kitchen window, and says, like always, in her cheerful, hoarse-sounding voice, Hola, mi amor.

Hola, mi amor. But where did you go? Why were you away so long? I know you didn’t get married just to go off by yourself like that and leave me alone here!

The weekend before we left for Mexico at the end of June, Valentina and Jim had invited us to their country house again. We were headed back to the city late on Sunday afternoon when Aura and Valentina said that they wanted to stop at a shop in town that we’d visited the day before. Jim and I and their smelly dog, Daisy, waited in the car and minutes later I saw Aura coming out of the shop with a new purchase clasped in her arms, a Joseph’s multicolored dream coat of a quilt, in a clear plastic casing, that she told me had cost only $150. A good price, I agreed, for such a beautiful quilt, and brand-new, too, no musty grandma relic. An affixed brochure told about the American artist who’d spent years traveling through foreign lands studying textiles and who now designed these quilts that were then hand stitched by seamstresses at her workshop in India.

A few days later, as we were packing, Aura came out from the closet carrying the folded quilt in both arms and laid it into the open suitcase on the floor. So she wanted to bring the quilt to the apartment in Mexico. And then she wanted to bring it back to Brooklyn in the fall? Así es, mi querido Francisco, she answered, with that lightly sarcastic formality that indicated she’d anticipated my skepticism. I rarely opposed Aura’s wishes, with the exception, I admit, of her wanting to move to a bigger apartment, or one with a garden where we could have a dog, because we really couldn’t afford to do that just yet. But this time I did oppose her. It doesn’t make sense, I said, to bring the quilt to Mexico and back with us in September. Look, it takes up almost the whole suitcase by itself. And don’t we already have a nice duvet on the bed in Mexico? But the quilt is so beautiful, Aura insisted. And we just bought it. Why should the subletter get to enjoy it before we do? Maybe we should just keep the quilt in Mexico, she said; at least we own that apartment. (It was her mother’s, actually; she’d bought it for Aura before Aura had even met me, though we’d taken over the mortgage payments.) We don’t have to leave the quilt out for the subletter, I argued. You can just put it away in the closet, and we can inaugurate it in the fall when we get back. Imagine how much we’ll miss the quilt this winter if we leave it behind in Mexico.

Without another word, Aura pulled the quilt out of the suitcase and carried it into the closet. She came back into the bedroom and resumed her packing in stony silence. For the next few minutes, she hated me. I was her worst enemy ever. I had to bite the inside of my cheek to keep from laughing.

After Aura’s death, Valentina told me that the quilt hadn’t really cost $150; it had cost $600. Aura had been afraid to tell me.

But it wasn’t just the money, I knew. It was that she didn’t want me to think of her as the kind of woman who would drop so much money on a quilt—even though I knew she was—in the same way that she’d get upset whenever I noticed that she was perusing celebrity gossip or fashion Web sites on her laptop while we read or worked in bed before going to sleep at night. She’d sit with the computer balanced on her knees, the screen turned away from me, emitting staccato spurts of typing, jumping from window to window. It didn’t bother me that she liked celebrity and fashion Web sites. Though that is exactly what would have bugged her, catching this glimpse of herself through my eyes, me supposedly loving it that my brainy superliterary grad student young wife could have the same enjoyments as any frivolous housewifey girl who never read anything deeper than People. That I could love that, that I presumably found that cute and sexy, that she could satisfy that cursi macho voyeurism—how embarrassing! At the end of a long day, she liked losing herself in those Web sites; ¿y qué? It had no significance. Even my noticing it at all was already a distortion or an exaggeration of who she really was. Why couldn’t I just keep my eyes on my own book or laptop? My defense was that I was entranced by almost everything she did and could hardly ever take my eyes off her. Really, I was just waiting for her to put the computer away and tumble into my arms under the covers. She knew that, too.

When I came back to Brooklyn alone from Mexico that first time after Aura’s death it was mid-September, hot and steamy. It seemed, that fall of 2007, as if summer refused to end, hanging over the city like a punishment. I ran the air conditioner night and day. But finally, with the first dip in temperature, I went to the closet and, just like I’d promised Aura, took the quilt out of its plastic case and laid it over the bed. The quilt was made up of thin horizontal strips of miscellaneous fabrics—every conceivable hue of bright color seemed represented, reds slightly predominating—arranged in parallel rows running lengthwise. It really did seem to vibrate before my eyes. The quilt added to the strikingly feminine aspect of what was now my widower’s bedroom. Stuffed animals and toy robots; a miniature ruby slipper dangling from a lamp shade; a big chocolate heart from Valentine’s Day a few years before, still in its cellophane wrapper and ribbon. Plush love seat in a corner, piled with big colorful cushions, next to the television. Wedding dress over the mirror. The carved, painted winged angel from Taxco with its scarlet-lipped white face of a lewd adolescent cherub, hanging from the pronged lamp over the bed, very slowly and perpetually spinning at the end of its nylon cord, fixing its wooden stare on me alone in bed just as it used to stare at Aura and I together, and slowly turning away.

Often in the mornings, when Aura had just woken up, she would turn to me in bed and say, Ay, mi amor, que feo eres. ¿Por qué me casé contigo?, her voice sweet and impish. Oh my love, how ugly you are. Why did I marry you?

¿Soy feo? I would ask sadly. This was one of our routines.

Sí, mi amor, she’d say, eres feo, pobrecito. And she’d kiss me, and we’d laugh. A laugh, I can say for myself, that began deep in my belly and rumbled up through me, spreading that giddy smile on my face that you see in photographs of me from those years, that goofy grin that didn’t leave my face even when I was reciting my wedding vows—Aura’s expression, meanwhile, appropriately emotional and solemn, if a little stunned—which made our wedding pictures kind of embarrassing to look at.

Aura put her quilt away in the closet and came back into the bedroom and finished packing for her death, three weeks and one day away.