9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

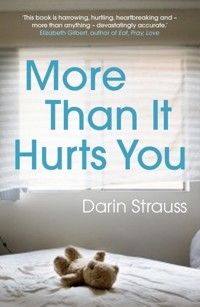

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Will this hurt me...more than it hurts you? Josh and Dori Goldin are the perfect couple. And they have a perfect baby boy: he is eight months old, he has blue eyes and tawny hair, and no, he hasn't started to talk yet. And he doesn't react to his name. And he did lose consciousness recently. And coughed up blood... And then his heart stopped. For no obvious reason. But young children always scare their parents... Don't they? More Than It Hurts You is the compelling and devastating story of a seemingly perfect family spinning into crisis: a mother accused of harming her child, and a father shocked into realizing that the people he loves the most may be the people he should trust the least.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

MORE THAN

IT HURTS YOU

Darin Strauss is the author of two novels – the international bestseller Chang and Eng, and The Real McCoy. Also a screenwriter, he is currently working with Gary Oldman to adapt Chang and Eng for Disney. His work has been translated into fourteen languages. The recipient of a 2006 Guggenheim Fellowship in fiction writing, he lives in Brooklyn, New York, and teaches creative writing at New York University.

Also by Darin Strauss

Chang and Eng

The Real McCoy

First published in hardback in 2008 by Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First published in Great Britain in trade paperback in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Darin Strauss, 2008

The moral right of Darin Strauss to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84887 003 1 eISBN 978 1 78239 543 0

Designed by Elke Sigal Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Sus—Without whom, zilch.

Contents

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part II

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part III

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part IV

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part V

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Part VI

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Acknowledgments

About the Author

MORE THAN

IT HURTS YOU

The old woman called her husband to her side. “Do you remember?” She asked him. “Do you remember how fifty years ago God gave us a little baby with curly golden hair? Do you remember how you and I used to sit on the bank of the river and sing songs under the willow tree?” Then with a bitter smile she added: “The baby died.”

The husband racked his brains, but for the life of him he could not recall the child or the willow tree.

“You are dreaming,” he said.

—Anton Chekhov

FIFTEEN MINUTES BEFORE HAPPINESS LEFT HIM, JOSH GOLDIN LED HIS summer intern by the elbow to share in the hallelujah of a Friday afternoon.

Work was petering out across Sales. The butter smell off somebody’s microwave popcorn settled on the cubicles and teased even the far offices—the first hint of weekend, and eloquent in its way: You are a bored and hungry creature; why screw around on the ’net when there’s fun in the coffee room? But that summer intern with her frown like shark gills at the corners of her mouth—Trisha? Alyssa?—lacked what Josh believed all of us are made for: knowing when to work hard and when to let up.

“You don’t think you can outrun the long arm of the weekend, do you?” Josh said.

He got familiar with people right away; he had that puppy quality, of never being a stranger to anyone. He acted cheerfully and blessed and it’s hard to believe that what happened, happened.

“The weekend? But it’s still Friday,” Trisha/Alyssa said, laughing, smiling—in other words acting unlike herself. She was a mumbler whose temperament was a kind of infirmity.

“You know, work,” said Josh, squeezing her elbow lightly, “isn’t only for work.”

They were walking really close. Josh moved quickly; each long stride was effortless. Alyssa/Trisha could barely keep up, her heart gasping for circulation. Yet she felt the usual pleasure, looking Josh in the face: his dimples, the constant wattage of his smile, his air of couldn’t-be-better. Very few people met life with a face that free of grievance. Of course, it helped to be very handsome.

“Well, all righty, then,” Trisha/Alyssa said. Her little laugh came as two hard breaths out her nostrils. “I never thought of it in that way, Mr. Goldin.”

Like many women feeling the first cool drafts of spinsterhood, Alyssa/Trisha worried about bad breath. She’d forsworn coffee—and so the coffee room—since she’d begun working at Sparkplug TV.

“Wait, let me understand this,” Josh said. “You haven’t been on break the entire week, is what you’re saying? That’s downright un-American.”

This was his specialty, teasing in feather touches. He never upset you at all.

“Well, Mr. Goldin. I’m really an Arab. Can’t you tell?”

“No doubt.”

She had goose pimples now, every little hair on her arms standing up. At the same time—despite the warm nudity of the boss’s hand on her—she found herself more relaxed than she’d been this whole first week. That’s the power of genuine attentiveness for you. The key was the tenure of that touch, the hand babying your elbow.

“I’m just kidding about being, you know,” she said, “Arab.”

“Yeah, sure, keep ululating—Muhammad.”

His normal smile was a pleasant, subtle mocking. But for tough cases like Alyssa/Trisha his laughing eyes, out of courtesy, took on a nearly female gentility; his curved black lashes touched at the corners. Josh had enough social generosity to create his music even for someone this dreary.

She didn’t pull her hair over her mouth now. She didn’t stammer just because this handsome man was making talk with her. (Josh had been aware of instigating this sort of quick evolution before.)

He got her to the coffee room at the height of somebody’s repartee.

Paul Damphouse, a young sales exec, roly-poly and bald too soon, was recapping a Saturday Night Live skit about the president. Office humor in a nutshell: impersonations of impersonations. For his size, Damphouse had a large head. For his sins, he had an ulcer.

“You bastards microwaving p-corn without me?” Josh said. With an athlete’s liveliness he hurried in. A smallish lounge was all, three men and one woman in it, everyone idling near a surprisingly crappy sofa. These people were assistants or planners: beneath an account exec such as Josh.

“Shit, it’s the boss. Hide the premium blends,” said Doug Moscow. He was a young guy glittering with the importance of an intern made assistant.

“Not the boss, my friend,” Josh said. “Just your boss.”

Moscow ticked his head back, a breezy wha’s up. At which point Alyssa/Trisha’s throat shut like a chimney flue.

“Hello,” she managed.

The light from the overhead fluorescents quivered. It jangled the nerves and gave everyone the appearance of being photocopied where they stood.

Josh gave Trisha/Alyssa a distinct nudge of a look.

But she just hovered there, frumped-out in a polyester skirt-suit. She was prim as Popeye’s Olive Oyl, with the same shapeless frankfurter torso. In the uncomfortable quiet—the only sound the latte machine’s revolving-door whoosh—everyone was waiting for Alyssa/Trisha to introduce herself. She didn’t understand and just kept smiling. But once a smile becomes a decision it’s no longer a smile.

Small talk abhors a vacuum. The other guy here, Mark Santella, started chatting about his teenaged daughters. Somehow a conversation got pieced together—Our kids, they’re crazier than we were. Well, you were probably never that crazy. Yeah, and what were you, some kind of goddamn . . .

As Santella and Damphouse crunched through this faux argument—Dude, you totally rock out for what are you, eighty? Well, you haven’t been shitfaced since I’m guessing junior prom—Moscow watched, like a cat following a Ping-Pong game. As the younger man, he needed to end up on the side that would win this crowd’s approval. Then he’d know whom to ridicule, and whose side he’d been on all along.

But Josh—flaunting his charm and celebrity smile, raising a Clooney eyebrow—quickly ended it.

“Hate to say this, but I’ve seen both you guys pass out from one beer.” He was a married man with a baby, and recently he seemed removed by half a degree from any childishness he might have joined in.

The coffee room was Josh’s forté. He felt comfortable everywhere, this airtime salesman who was the reverse of the old joke: He had no acquaintances and many friends. But he could really open up his charms here, where your schedule lobbed you a mock day-off a couple times a day. Late Friday afternoons were the best, of course: the week already throttling down, relaxing into quoted movie lines, ribbing, more open flirting, and the anticipation of home. This newly refurnished lounge had been done up with imitation school pennants (“Sparkplug Spirit, ’07”), an exhausted sofa, scuffed Led Zep stickers on the fridge; a perfectly balanced stalemate of Yankees and Mets paraphernalia; an injury-retardant Nerf dartboard (never used); some 1970s-vintage posters of Lee Majors. But somehow, all these theatrically dirtbag touches sort of didn’t add up to anything. Prior to Sparkplug TV’s new regime, the coffee room had been merely drab and impersonal. Now it was impersonal, drab, and wacky. (This residue of counterfeit wackiness having been the dot-com culture’s dying gift to legit business.) Still, the lounge was alive—who wouldn’t want to hang in the only break room? Or, at any rate, it seemed warmed a little by the joking that had accumulated there.

In fact, Josh probably felt more at home here than at home. No one nagged him here; people understood that a sales dinner wasn’t all fun. It was work, too.

Josh took the first scalding gulp of his coffee. He didn’t join the conversation, but—by giving confiding looks all around—he lent the break his unspoken clout and felt happy. He was the smartest guy in the room. Other afternoons, for fun, he might have charmed his co-workers into making little revelations, job qualms, misdemeanors, nothing too serious, just a flutter of anecdote to close out an afternoon. But he preferred this more humdrum kind of break, because then he could just unplug his brain (a sales rep named Kate Wilbur was telling everybody a story about a sales exec at MTV Networks, and Josh grabbed a few snacks from the Styrofoam cup without registering what kind of food it was)—really, what could be better than bullshitting with people who were more or less like you, nice, unpretentious guys, not perfect maybe, but good people at the end of a good, hard week. Guys like Moscow (Moscow who, with the helplessness of a boy stealing bites of cake, couldn’t quit eyeing the sloping shelf of Kate Wilbur’s breasts), and guys like Paul Damphouse (although Damphouse was a little weird, smiling when he talked and scowling when he didn’t, as if rationing his anger so that in conversation he might be an average human being). Even Kate Wilbur here was basically cool. Except she hoarded stockpiles of gum and cookies. Her heavy mascara threw him, too; her eyelashes were clotted black like the tines of a muddy rake.

And she kept on hemorrhaging talk: The dude she knew at MTV had been a buyer at PHD Agency before jumping to the sales side for a buttload of money—MTV paid great—but the guy totally had carb face now. As Kate said this, her shrug added a postscript: It said, All single men have carb face, at least the ones I meet. Josh realized that the snack he was eating was Fruit Skittles.

So, anyhow, carb-face-guy replaced some dude who’d overestimated the market, holding inventory back. A huge fuckup. Then MTV ended up cutting spot prices in the non-upfront thingy—the scatter market; that’s what it’s called, thank you—by as much as what? Fifty percent? Sixty? All right, so not everyone is good at telling a story. Kate was still pretty cool in Josh’s book. Even Alyssa—that was her name—was almost cool. She was eyeing her knuckles, head down, her cheeks tomatoes of unease. But hadn’t he shared kind of a good time with her walking over here? Josh lived his comfy life by having faith in people, faith that whoever he met was like him in some central way.

He happened to look out at the reception area, and saw some kind of fuss. His secretary, Damita Melendez, a phone on her ear, tensed, blinked—whatever she was hearing had her ripped.

Boyfriend dump her again? Josh leaned forward to peek.

Damita was putting a hand to her very emotional face. Her light brown cheeks had gained in color like steeping tea. And now she was hurrying to the break room—to Josh.

“I’m the type of guy, I had to cut prices fifty percent? I’d chop my own nuts off,” Mark Santella said. He talked in that loud interrupting manner perfected on NFL pregame shows: language as a punch in the arm. “Really, I’m the type of guy I think I have that work ethic. I’m not saying that your friend’s a loser necessarily but all I’m saying is if I could chop my own nuts off.”

Damita Melendez reached the break room. Josh tried his paternal face, his squint of experience—because what is a boss but a nine-to-five father? But right away he felt there was some reversal. Somehow she had slipped past his preparations. Here was the beginning, the first mystery blip on the radar sceen.

“Uh, Mr. Goldin?” she said. She fidgeted and stared dumbly with a hot face. “Your wife left a voice message. It’s, um, it’s Zack,” she said. Zack was Josh’s eight-month-old. “Uh, he’s—” Then she let out a noise streaked with tears.

It’s one of those human quirks that no one can account for: but the first reports of horrifying news often cause giddiness. Josh gave a laugh, feeble and quick, that he’d regret forever. “What?”

Damita only said, “Something terrible—” and with these words snapped Josh’s life into before and after.

In the sudden pressure drop, Josh said: “Zack is what?”

Everybody else looked at one another uneasily, furtively—the same way people in a crowd hearing of a pickpocket will unconsciously feel for their keys and money. Everybody but Josh had the passing thought: Does this affect me? Am I all right? Which got replaced right away with the soggy, recalibrated belief that, somehow or other, Josh might be at fault here—It’s a shame that his son is sick or might even die because he’s a really good guy, at least on the surface he is, though maybe people have to do something to deserve stuff like this; maybe Josh is a bad parent or person, unlike me. All this in half a second.

“Oh, God,” Kate Wilbur said, with a promiscuous woman’s special reverence for family. She was crying, ruining her mascara. “Oh, my God.”

It seemed Josh was watching a movie. But the dialogue and the lips weren’t quite synched up. Except for a few words—the words most people have the luck not to have much practice with: intensive care, lost consciousness, blood—he missed what she was saying.

Damita stopped talking anyway. She felt terrible: Probably she should’ve gotten Josh alone to tell him. I never do anything right, she thought.

JOSH—AS IF he’d fallen from one movie into another—found himself outside, racing through the office park. He gripped his car keys without remembering having taken them. The office buildings he passed were geometrically simple and ugly in the tipped-over-refrigerator style. It was a world of tipped, ugly immensities.

What exactly had Damita said? Josh was now at the door to his Lexus. Zack couldn’t have stopped breathing. That would mean he wasn’t alive. The car’s black roof was sequined with raindrops. Had it rained? What Josh became aware of next was the flap of the windshield wipers, that metronome. He was driving along the L.I.E. service road, it was raining again—he was aware of that.

Intensive care, lost consciousness, he thought. And then he let the associations drop there.

The word he didn’t confront devastated him. It was like something heavy and leaning behind a door that he didn’t want to open. Yet in what was this ongoing movie he still didn’t feel the word’s full power.

His life was coming as if through a sieve.

Coma, Josh thought—that was the word. He got slammed by a fist of panic and almost lost the wheel of the car.

In the days when she’d worked, Dori had been a blood taker, a phlebotomist (after the second Austin Powers came out, Josh called her his phlem-bot). Whatever was happening, she must have things under control. That was one benefit of having married into medicine. Just calm down here.

Josh was pinching and wriggling his cell phone out of his pocket.

“Hi, you’ve reached Dori’s cell phone . . .” Voice mail. A fierce betrayal, that spirited hello, as if the bad news hadn’t reached every shadow of her.

Josh realized his car radio was on. WFAN’s 20/20 Sports Update: Derek Jeter had rolled an ankle and would have to go on the DL. This stole Josh’s concentration—Shit, right in midseason? Immediately there was the firmer, canceling voice in his head, Forget Jeter! What’s wrong with you? But maybe being distractible through a crisis is another way we protect ourselves, the body guarding against terror as against infection.

And then Josh’s brain left the road again. He looked into the window of memory, a neat square cut into years. Right after the baby had come out—wrinkled head, scrunched E.T. face—Dr. Feldcamp had asked whether Josh wanted to hold his son. This had been right there in the delivery room, with all that blood and the thick salt smells. So he carefully rested the video camera on a flat, dry space by the birthing table. He took the twenty-inch-long purple thing into his hands, how do you hold it, all the while the creature squirming and howling. His son really had looked kind of freaky, too, if you thought about it. Not so! He’d had this solid, living weight, and I loved him right from the start. But what Josh actually meant was: Had I loved him right from the start?

His newborn son was the one person Josh had ever met without feeling an instant connection to.

“No no no”—Josh punched at the radio; turn that goddamn thing off—“Why think that?”

He exhaled. Rain had grayed over the world. The wipers smoothed water away, waited, smoothed it away again. He wanted so desperately to be at that hospital already; he was also afraid to get there.

The first day of Zack’s life Josh had watched the baby in a hospital bassinet, sleeping on the other side of a glass wall. Wrapped, cleaned, peaceful, and, somehow, but clearly, his. Is that not love?

White, tall St. Joseph’s Medical Center, like a fort, had a windowless face and held the top of a smooth, mowed hill. He was so close now. Josh sat trapped at the red traffic light across the street. He thought, My son is in that building. It seemed to be an hour, just to gather air in through a nostril, feel it curl and unwind through his lungs, and then to let it out, all with his eye on that fixed red circle.

Josh would have given his house, his car, screw it—his own health, not that it’d ever come to that probably—to have this be a misunderstanding, an overreaction. Didn’t the actressy part of Dori exaggerate sometimes? The baby wouldn’t have had to be perfect, mind you, just alive and minimally damaged. Not brain-damaged, though. The typical American secular Jew’s approach: backing into prayer. Not that the antique alphabet of devotion was anything but gibberish to him. But Josh’s inner voice begged with his idea of God anyway, a sort of wily old solid midwesterner with a Kringle beard. In this negotiation, he could tell that the old campaigner saw through him—what did Josh really have to offer?—and so he found himself repeating “Please,” over and over. “Please please pl—”

Green light.

Then the ridiculousness of trying to find parking when your kid might be dead. A black hulking Range Rover, swaggering into the last available spot, nearly crushed Josh’s bumper. He hurled curses, orbited the lot again, and then raced to the red cross-hatching of a no parking zone. Then he was out in the rain again—his headlights on, screw the beeping—and sprinting to the glass door whose sliding open would allow him, at last, to apply his confidence to this disaster.

Inside the wide-open brightness of the emergency room, the sodium light handed out a little frazzle to everybody.

“Okey-dokey, let me just check,” the admitting clerk said. She’d been on her headset phone before she’d noticed Josh. “Goldman, you said.”

“Goldin.”

A salesman is a professional noticer. The nurse wouldn’t look him in the face—probably embarrassed by the rings under her eyes, which were brown: like where napkins have been stung by the coffee cup. Even now, Josh felt tuned in, awake to the human cues. And getting this woman to like him seemed the first step toward assuring Zack’s health.

“The baby’s eight months,” he said. “Zack Goldin.” His voice broke when it touched the familiarity of the name.

“Ooops,” the nurse said. The far corner TV ran a sitcom at midvolume, Everybody Loves Raymond. “Sorry sorry sorry,” said the nurse.

She squinted her eyes to slits of inattention. Josh even wondered if she might still have a friend connected to her through the earpiece. Nurses who seem to lack feeling must do it for two reasons. Either they have an epicurean’s taste for blistering arguments, or they’ve got so much compassion it’s a risk to reveal any emotion at all. Then again, only a saint would reflect, Hey, this is life or death, for every patient, every time.

Josh was leaning on the desk. Under his elbow, some waiting-room detritus: a New York Post, back page up, “Boston Comeback Sinks Yanks.” He was kind of wet from the rain; his elbow print was a gray continent across the photo of Josh Beckett. It was amazing how distinct, how spotlit, everything in a hospital was.

“Here we go, Mr. Goldin,” the nurse said. “Isaac, age thirty-five weeks.”

Then her face had a nervous moment. “I’ll—have to let you talk to the attending, okay? I’m sending an IM upstairs.” (A lot of suspicious overblinking.)

Josh rummaged through his jacket pocket. His shirt was sticking to his chest in splatty flaps.

“Oh, sir, I’m sorry. We don’t allow cell phones in the hospital. They’ll be with you shortly, okay? I sent an IM.” (Already back to tapping at the computer. Was this for show?)

He dialed anyway. And throughout the dialing he had this thought: Four months.

“Sir, the machines are very sensitive if you use your cell phone. It’s a rule for a reason.”

Josh’s eyes went violent. “I’m trying to find out what’s wrong with my son. I’m calling my wife. Do you want a scene here?”—Josh taking a stand, feeling as if he was at least doing something—“ ’Cause I’ll make a scene.”

And it was pointless anyway: . . . you’ve reached Dori’s cell phone . . . The hospital kept humming all around.

Many times when Josh sat at his desk alone at work, chatted with an E.V.P., or joked his way through a business lunch at some American Fusion restaurant—anytime he happened to find himself without his wife—he had a strange thought. He almost believed that Dori was at his side, a dark knockout with a high, old-fashioned forehead. For Josh, marriage was companionship that never stopped. But he felt entirely by himself in this emergency room. A hundred percent alone.

Four months, could that be? That was when Zack had first smiled—had first seemed actually to recognize his father. Josh hadn’t felt genuine love for his son right away. He had to admit it—it had taken months!

Dori appeared in front of the elevator. Searching for Josh, standing in her queenly way, a frown tugging her soft pale lips. Even now, her particular beauty was the thing you noticed first—the sly width of her temples, the vivid throat, the mouth whose fleshier bottom lip obtruded like a drawer left partway open. Her skin took even this unflattering hospital light and did something dulcet with it.

Josh met her face across the waiting area—“Honey!”—and reached her in what seemed two floorless strides. From the television came recorded applause, as if endorsing his hopefulness. She was wearing his old Reggie Jackson shirt.

Right away, he came out with the panicky, high-pitched inevitables. She just took him into a hug. He had the soft of her body, at least.

“No, it’s not good news,” Dori said.

Somehow it was the girlish voice he’d heard each day for the past eight years—in bed; at parties; over morning coffee; in the cars they’d owned; on airplanes; a voice that so often delighted in the sunlight and in the dark, a voice that signified to him the assorted teeming sentiment of family itself—telling him, “It’s not good news.” She went on hugging.

“He’s under observation, we don’t know”—and her perfume (he’d smelled it just this morning) lifted into his nostrils again, there was sweet familiarity in it, everything’s got to be okay. “Thank God you’re here,” she said. She didn’t know a thing about Turkey, or even like to discuss it, but she was part Turkish, and that dissident splash gave Dori her proud, uncommon look.

She told all: that Zack had been fine, just sitting in the Baby-Björn, they’d been in Pathmark, but around noon he just started kind of throwing up. She wouldn’t have worried, but there’d been blood in the throw-up. Not much, but any is some. It had been terrifying and awful. By the time they reached the hospital, this doctor had had to push on Zack’s chest to get his heart going again—her voice staggered a bit here—because Zack “coded.”

Jesus Christ, but was the baby going to be okay? This, finally, was the real terror, the trapdoor, the abrupt fall.

“Well, thank God he’s breathing normally now, which is great,” Dori said without histrionics. But her mouth, dry and pulpy with trembling corners, gave the game away. “No, I don’t know. I think probably yes. They were actually going to send him home at first. But then he passed out—”

“Thank God?” Josh said, with a stringy feeling behind his knees. Using all his mental strength just to follow along. Thinking: This is allowed to just happen to regular people?

Two old ladies walked right at Dori and Josh. They parted around the Goldins and then closed ranks again—crying as they went. That was the thing: Everybody in this emergency room was draped in her own concern.

Dori showed Josh her gallant cheeks. He had an impulse to beg forgiveness. He couldn’t think for what, but then realized it was for not having loved Zack quickly enough. There had also been that silly, mostly innocent thing he’d done that time. Dori never knew about it, and wasn’t it stupid to think that that thing, that one worthless dangling thread on the steadfast embroidery of their marriage, was relevant now?

Josh was about to ask Dori to take him to Zack when she said, “Let’s go there together.”

THROUGH THE CORRIDORS of Pediatrics a disheartening smell floated in waves. It was composed of rubbing alcohol, plastic, and, very faintly, shit. You could taste that hospital mix on the back of your tongue. Dori hurried them past a statue of Big Bird. They followed a trail of paw tracks that had been painted on the wall. All this nullifying cheerfulness (smiley faces peeping Kilroy-style around corners; clouds painted by the light fixtures) was made even weirder because the rooms they passed were beeping. There was no way to soften or disguise life-or-death machines.

Josh believed he could get over it—that is, if, God forbid, it came to that. But how grindingly, obliteratingly sad that there were so many people in the world who would never meet his son.

And could she get over it? he wondered. Dori had started crying gently; her pale eyes had the lit-from-within color of nighttime swimming pools.

A long-faced black woman stood at the entrance of the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

“Excuse me.” Josh peered over the woman’s shoulder. “But we’re looking for the supervising doctor.”

“You’re in luck, then.” The woman laughed shyly and at the same time a bit touchily. She was two women, one of them offended.

Dori said, “This is Dr. Stokes.”

Well, that was it, then: This black doctor would think he was racist. All through his body Josh felt his heart going, felt the great thump! of worry. The doctor would take it out on the baby. Maybe not in an overt way. He wanted to tell this black woman that, even if Dori didn’t look it, she had some Turkish blood in her. So how racist could he be?

He didn’t trust a thing about this doctor’s looks. She wore her hair bullied straight back. Suddenly Josh was sure Zack was already dead. They were keeping it from him.

Meanwhile, Dr. Stokes moved ahead into a flash flood of confusing talk.

Something or other in vomit shows that gut obstruction could be a possible something. Gastric something lavage. AVM. Stool guaiac is the most common form of something occult blood test. When Josh pressed his closed eyes with his thumb and middle finger, it made fireworks in his lids. For this test the baby would have an NG tube up his nose, and then we inject saline, which we suck back up to look for blood. Josh opened his eyes. The doctor had a slumped-forward way of standing, which gave her lanky frame a false impression of weight. Some of her phrases, as they slipped by, did have a familiar grabbable part or two, and Josh made a collection of words he recognized: Checking for tumors. Possibly fatal.

Hospital was a language Dori spoke. “Okay,” she said, “but all that is highly unlikely, right?” She was nodding, grilling the doctor, her voice flicking up into melancholy competence. Thank God for Dori. Josh always found it kind of a surprise, like a holiday whose calendar location you forgot, to remember she knew things he didn’t.

“Dr. Stokes, we really appreciate it,” Dori said. She let a gulp of hesitation pass. “Still, if Zack’s vomit had blood in it, why did no one check his coags?” Even surrounded by makeup smudges her eyes, deeply open now, shed their bright blue. The effect was striking.

“Wait.” Josh said, “There was a screw-up? Somebody made a mistake?”

The doctor’s barricades withstood this; she had a tantrumrepelling calm. “I’ll look into that, Mr. and Mrs. Goldin. I can tell you, however, that the ER note reads—”

“Can we see him?” Josh said, pleasantly but not without some starch in it. Even here, he wouldn’t take on the lowercase life of an Alyssa. “Please, Dr. Stokes, I’m just his dad. Where’s Zack?”

“Honey.” Dori quietly took his arm. “They’re running tests right now, Josh. All of us need to find out what’s wrong, okay?”

“Right.” Josh felt an uncried cry wedged in his throat. “Of course I understand that.”

As with everything he’d said the last unthinkable hour, this really meant: Please, I’m just looking for someone to tell me what’s going to happen.

Dr. Stokes tried a smile at Josh, tried to avoid the condescension that passes between doctors and those who need them. The professional face of physicians and prostitutes: the mouth getting the job done, the eyes belonging to somebody else. The presumption of Dori’s “All of us” seemed to have annoyed her.

Dr. Stokes turned once more to Dori, whom she’d fixed on as the spouse in charge. According to the emergency-room note, there’d been no symptoms to indicate that someone named Dr. Weiss should have checked “coagulation factors.”

That drab imitation warmth, the stiffness—This is the best try this woman can give us? Josh wondered.

“I mean, I know what I told that other doctor,” Dori said. She drew herself up into a hallowed dignity—a mother guarding her cub. This was beyond the pettiness of who said what. She wristed her cheeks dry.

Did the hospital blow it? Josh thought. Is that what happened? I have to find out if that’s what happened.

Dori brought her hand to Josh’s damp face, which was the way he learned that he had started crying, too.

Dr. Stokes’s eyebrows arched politely closer together. “I know it’s very hard to process right now,” she said. This was more than hospital consolation; it really did seem genuine. It must have been the result of Josh’s crying. Men’s tears, like any rare and glittering commodity, always get people’s attention. Josh’s son hadn’t even spoken his first words yet.

Dr. Stokes had the edgy officious person’s inclination to keep talking even after the point had been made. “I do understand, really. I’m a parent myself. I have a seven-year-old boy. Your child is in expert hands. I can promise you.” Then she threw a glance at something or someone down the hallway.

“We’ll have more solid information after his liver-function tests. Please. But you’ll have to excuse me now.”

An Asian nurse arrived at Josh’s elbow wearing all pink. She told them in a quiet, candied voice that, pardon me, Mom and Dad, it’s time to leave the ICU. “Let the doctors do what they do best.”

The nurse’s plastic name tag had a teddy bear sticker on it. They were marketing the hospital experience to toddlers. But what good did Josh’s noticing do him now?

The nurse put her hand on Dori’s elbow to move her gently along. They all saw a suburban mom in a Yankees shirt, another minivan panicker. Only Josh knew how trained his wife was.

When Josh leaned in to shake Dr. Stokes’s hand good-bye, he realized he was still holding the New York Post he’d first seen in the Emergency Room. He didn’t remember having taken it, but here it was. “Boston Comeback Sinks Yanks.”

FEAR OF TRAGEDY prowls the margins of every decision to get married. In an emergency, companionship becomes essential where it had been only pleasurable, substantial where it had been light. The proverbial comfy old chair has to become a life raft. Everybody will need this someday; everybody knows it.

Whenever she’d come to Sparkplug get-togethers, Dori had gotten covered by that spouse-camouflage thing that happens: She’d blended in with furniture and other nonoffice people. Even worse, Josh had always been a prick about visiting Dori at her work. But now, as they rode the elevator downstairs, he looked into her confident face and thought, What can I add here? Dori spoke fluent hospital. His talent was fluffing people’s mental pillows; he got others to open up, to share surface truths: to bullshit.

Five stories under Pediatrics, in St. Joe’s cafeteria, the wall clock had an advertisement on its face: “Norvasc (amlodipine besylate) is the most prescribed branded anti-hypertensive agent in the world.” The clock read 7:32 p.m.

Josh worked at figuring this whole thing out—the million-to-one of a sick child, the hospital’s fuckup, his maybe sonless future, everything—but it made him tired. He felt numbly dismal. Dori would have to explain it all. She’d gone to the bathroom.

Josh bought two cellophane-wrapped apples, yogurts, a shivering Jell-O, and he waited for her in a padded booth. (The Goldins were healthy eaters.) These apples were deviously wrapped. Opening one, he lowered his head in concentration. He always found Dori a booth when he could; she liked them better than regular tables. Someone had scratched the initials “D.H.L.” on the seat here.

A shy-mouthed Hispanic kid made his way past with limped, wary steps. He seemed to be moving in slow motion. It was a slow-motion world down here. People sluggish with contagion, with shitty luck. The kid wore the disbelieving face of misfortune—that sense of a promise broken. In the absence of wood, he was knocking on his head. Everyone with their stratagems, their God wooing; everyone with some kind of rabbit’s foot against the worst.

Josh, a genius of optimism, had no talent for despair. How could he have? When Josh had been a kid his own father would lift him to the ceiling and goof: “Nothing bad can happen to a Superboy.” He’d lived happily, he was coveted and appealing, he entertained, but Josh’s imagination was limited. It didn’t stretch far enough, that rickety bridge, to lead him to the unfamiliar. And yet, sitting in the cafeteria—he pictured Zack’s funeral: shiny brown coffin, yellow bulldozer, sinister hole in the earth. (Were there special coffins for babies?) He imagined shoveling the dirt himself, everyone super-quiet, the only noises the earth scattering on the polished lid. And the crying. Josh even guessed how a baby’s death might feel—an eternity of never being able to talk.

Now he felt his wife’s stare on his cheek. And heard the familiar sound of her, the thumbprint her presence made in the air: “You all right, Mr. G.?”

Watching Dori usually showed Josh his own reactions happening across another face. Husband and wife had been that synched up, secret-sharing, when things were normal. So he expected to see his anxiety cast back at him. But Dori wasn’t simply a reflection of his life, not now.

She stood before him with her steady chin and her steady breathing; the eyes were tensed, but in quick evaluation.

He asked if something else was going on, if the hospital screwed up.

“Just don’t worry about it,” she said. “It’s not really anything.”

There are shifts between husbands and wives that feel tectonic. She hadn’t even sat down yet; they stayed there looking at each other, these two people who’d had so little practice in the crash tests of life. She’d meant, of course, that she would be the one to worry about it. Cheerful wall-posters added to the vibe (Watch for Wellness and You! Menu Solutions; Better By Design Means . . . Healthier Cuisine) of tragic tedium here.

“Tell me, honey,” Josh said. “Tell me what they did.”

Dori sat. She leaned her elbows on the Formica conspiratorially.

“Okay,” she said, “I didn’t say anything to you about it, because, well.”

She was using the lively if hushed voice of risky collaboration. Some middle-aged eavesdropper at the next booth couldn’t hide his gleam of curiosity. It was clear to him that the Goldins were sheltered in the force field of marriage. They were a team against something awful.

“It’s just,” Dori was saying, “they were sort of surprisingly dense and rude, these doctors. At least this guy Dr. Weiss from I guess Pediatrics was.”

Just saying this relaxed Dori’s face terrifically. “ ‘So, Mrs. Goldin, it’s probably only a little stomach thing.’ The doctor actually told me that at first. He just sent me and Zack on our way, like it was nothing.”

“Is it possible that’s all it is?” Josh said. “Stomach thing?”

“A child’s brought in, there’s blood in his throw-up, and that’s the best they come up with? No”—Dori’s voice was a near-laugh. There’s a surprise invigoration in sharing even joyless confidences. “ ‘Oh, have some Pedialyte, Mrs. Goldin, we’re done, go home now.’ And then he codes.”

Josh waited. He waited for the electric bolt of recognition. It never came. He sat there with his bewildered eyebrows.

“Okay, so,” Dori said, gentling her husband out of his ignorance. “The first thing you’re supposed to check, when a baby throws up blood, are his coagulation factors. You test coags when there’s bleeding or bruising. Especially in a young kid. It’s the way to determine like if you have vitamin deficiency, if you swallowed something you shouldn’t have, or—”

She lopped off her explanation here and it was obvious why. There would be pain in getting specific. Coag testing can show liver disease, uremia, cancers, bone marrow disorder, horrors all.

“I just wish,” he said, “I knew more about medicine.”

Now and then, Josh would fail to understand things. This had been by choice as much as anything else. He’d let, say, a nothing detail at work elude him; or one of the problems of the female variety that husbands, through some osmosis of marriage, are expected to figure out. He was a skating-by expert. And he’d been this way ever since his terrific puberty. He could simply mimic comprehension, if he needed to. In a pinch, using his natural smarts he could eventually grasp most stuff. But even that little effort was generally unnecessary. He’d just play up the cool and enameled part of his personality—without even realizing he was doing it. And time and again, people seemed to admire that Josh Goldin didn’t give them his full attention; they just wanted to be near him. And, if he had been genuinely warm and fun with them, they saw in him whatever he had needed them to see, whether that was different from the way he really was or not. But now he was in a hospital, failing to understand what had gone on with Zack—what was still going on with Zack. And so Josh saw his force of habit, his windup luster, for the social vocation it was.

“Hey,” Dori said. “Hey.”

She spoke in her softest voice. “I didn’t say anything to you about it.” She leaned closer. “I didn’t want to worry you, is all.”

Still, she wasn’t done unloading. They’d also claimed, apparently, these stupid doctors, that she’d never alerted them that there’d been blood in Zack’s vomit. But she had alerted them, as soon as she’d come in. So they’d sent her home. But then Zack passed out in the car, right outside the hospital. When she’d run back in minutes later, with Zack unconscious in her arms, they snatched him from her and hooked him up to a respirator and got his heart going again; they’d also called her a liar. They said that she’d never told them about the blood in his vomit. Crazy what these doctors you trust your kid with are capable of, but it’s lucky that I, the truth is it never should’ve—

“Wait,” Josh said. “You were here twice? Why didn’t you call me right away? I mean like the first time?”

She chewed on her lip. “I didn’t want to bother you,” she said. “I know you don’t like to be bothered at work with this kind of stuff. It’s your crazy time, you said, with the scatter markets. You get so irritated when I interrupt you.”

“You didn’t want to bother me?” he said. “Oh, honey—”

He lifted his face that still had the clean look of shock and guilt on it. That shy-mouthed Hispanic kid passed their booth again, with his obliterated way of walking. Weren’t there babies getting born somewhere nearby? Shouldn’t some people in here be wearing goodnews smiles? Then Josh realized: People with good news didn’t stick around hospitals. So that’s why the underwater stupor here looked unanimous. Except Dori—Dori didn’t look that way. With a wife’s determination, she was making her eyes call out to him.

“Josh,” she said, retreating into professionalism and its associated comforts. “They didn’t. They didn’t check the coags until I’d brought in Zack again and made them. And then they pretended like I’d never asked them to in the first place.”

He shifted in his seat. “If they fucked up,” he said, crumpling a wisp of discarded cellophane, “we can’t let that slide, honey.” With something like a school bully’s listless anger, he kept balling up that cellophane.

Josh’s eyes, downward slanted, reminded Dori of something in his personality that she’d forgotten. The lids, small and creased, with faint red tendrils raking out above his lashes, may have been the only unappealing thing about him. And most people never noticed them.

“If they fucked up, honey,” Josh said—all his focus keyholed around this single hard detail—“we can’t let that slide.”

“Hey, listen to me a second, Mr. Goldin,” she said.

Her whole manner had lightened, had spread out. She was optimistic, kind of breathless, flushed, very beautiful. Her chin was up. “We’re going to do this. We’re going to get out of this okay. Sometimes babies just have kooky episodes.”

She gave him her straight-on look, which stopped him from fiddling with the cellophane. “Listen. We need to make sure they don’t get in the way of Zack getting better, is what we have to focus on.” She was still showing Josh that look—her bright blue dignity. “If we can just stay really smart and watch them, okay?”

She quit talking, in case Josh had something to add.

“I’m going to get on these fucking people,” he said.

Dori seemed about to grow brilliant with emotion again. But she tamped herself down.

“It broke my heart, seeing you cry like that,” she said gently. “Up there, with the doctor, I mean. I never saw you cry before.”

Josh pulled back. “Well,” he said. He now imagined his few restrained tears as having looked much worse than they actually had looked: his nose wrinkling, his cheeks blimping out, totally unmanly. “I’m okay now.”

In the conversation-reset that followed, Dori began silently arranging the contents of their food tray. Even her automatic little movements seemed to have the aptness of insight.

He had never known her quite like this. A year ago Josh had seen her become round with pregnancy; she’d grown taut as a grape, then dwindled back to herself. And now here they were.

“When you said babies just have kooky episodes sometimes,” Josh said—gobbling up every bit of hope. Thoughts had started to take shape in his mind—in the way that discrete images begin rising from pages of squiggles in books of ocular gimmicks. But then they died away.

“I don’t know what that means, episodes.” He shook his head. He wasn’t used to changing his self-assessments, but now he was apparently the kind of person who couldn’t take care of himself.

He understood only that there existed a motherly power he didn’t understand.

“Josh, if nothing else bad happens in the next few hours, and we watch him closely—the body is just a mystery sometimes—I really think he might be out of the woods. The next hours are really important. Think positive thoughts,” she said, even as she began quietly to cry.

He reached across the table. The love that husbands declare at weddings is nothing more than a grainy snapshot compared to the vivid feeling, the full 3-D love in sitting opposite a wife who is saving your family. Maybe that motherly power even held absolution for whatever he’d done or was doing wrong. With prayerish appreciation, he put his hand deep into her heavy hair.

“Oh, Mr. Goldin,” she said, and closed her eyes. This was her frequent nickname for him, less a joke than a message—together they’d traveled to the ends of intimacy and come full circle into pretend stiffness. He dried her cheek.

And she read his thoughts because she said, “Okay, let’s go check on Zack.” For years afterward, he’d remember the optimism that fired up even Dori’s itch to hurry from her seat, and he’d feel destroyed.

JOSH STARED DOGGEDLY at the elevator buttons. The glass that covered each floor number was convex; the lighted buttons made perfect glowing domes. Josh started crying. He looked at his feet and swallowed back what he could. You can hold it in, he thought. Come on. But right then he got reduced to shuddery weeping. He turned his flushed wet face from Dori, to the wall, as if that would hide what he was feeling. Dori went to pat his neck—but then she thought maybe Josh didn’t want his crying acknowledged. Men are weird about that stuff, she knew. Her hand lingered in the air like an awkward pause. She did understand her husband. Probably because she’d chosen not to caress him, he quit crying. The faucet had turned off and all that emotion shut up inside him again. Then she touched his face.

“EXCUSE ME” DORI said to a skinny young male doctor as she and Josh reached the Peeds ICU. “I’m here to see my son.”

“Oh, Dr. Stokes stepped away,” said this kid physician, maybe having misheard. A stethoscope clasped his neck with its monkey arms. “Dr. Stokes is not here now, so.”

“We’re actually here to see Zack Goldin, the patient,” Josh said, squinting. He held his big, attractive head at a slant. He was going eye-to-eye with the doctor. “Zack’s our boy.”

“I’m Dr. Weiss.” Put at ease by Josh’s manner, the young doctor smiled. “I met your wife, uh, earlier.”

Josh felt more at ease, too. Even in this place of wires, of oscilloscope blips; even in this recondite nerve center. His storm winds had died down.

Part of it was the dorky and Jewish-looking doctor standing before him. Though Josh had never met the guy, Dr. Weiss was a totally familiar person: the bad posture, the bony nose with its hourglass bridge. Josh had known kids like this at sleepaway camp. Brillo-headed, delicate, bodyfatless nerds—guys who lived socially by the occasional, sidelong acquaintanceship with people like Josh. This Dr. Weiss was somebody you’d remember as having worn glasses, even though he hadn’t.

Dr. Weiss spoke in that abstracted, tapering mumble of doctors and academics. He explained that, because the baby’s “crit” was low, they couldn’t see Zack right now. Josh thought he heard the doctor say that they would have to transfuse Zach’s blood.

Josh looked to his wife for translation, but Weiss kept on.

“Zack has stabilized, though, is what’s welcome. He’s breathing on his own, and he’s becoming alert—you know, interacting with his surroundings.”

Stabilized. Crits, transfuse—those gave Josh that stalled feeling of noncomprehension—but everyone knew what stabilized meant. Josh was dying for moments spoken in the daylight language of health, when Zack’s condition would peek out into the real world of words that he knew. Still, Josh turned to Dori, just making sure. Stabilized: the possibility of happiness, like one more signal noise pulsing in this hospital, cast its throbbing suspense.

Dori smiled. Sometimes, beauty springs from relief: crinkle-eyed, feminine head tilt, mouth half open. But what was all this medical-term bullshit, what about transfuse; what was that nag of doubt?

Dr. Weiss had long nervous lips that clearly registered self-reproach.

“I should tell you,” Weiss said in a flat tone, “as a precaution.” He swallowed. Amazing that he would have done this to them. “We have to rule out a source of upper GI bleeding that could return,” he said.

His face went grim. He’d blown it; the parents’ hopes were too high. “And there’s still the, well, the issue of determining the source of the bleeding.”

Then Weiss smoothed his green hospital smock; he regained his self-assurance by talking importantly: a monologue that Dori could follow, but that left Josh at the curb. It felt like being in Paris having only kindergarten French but being asked to negotiate a hostage situation. Esophageal varices; longitudinal; superficial venous; more terms and once in a while the clear words satisfactory and life-threatening—which made Josh’s hands damp.

Weiss faced the Goldins with high-nosed brusqueness. He’d reached the one element of his job’s stage business—the doctor polish, the doctor stability—that he felt he’d mastered: the quiet.

Dori said, “Are you a med student?”

Her voice came out mocking, dangerous—only Josh recognized it as the compromise result of clashing emotions. She withheld much nastier questions. “I mean, are you even a doctor?” she said.

Weiss rubbed his eyes, rubbing behind the lenses of those glasses he didn’t have. “I’m a resident.” He took a while to pacify himself. “Your training is as a phlebotomist, Mrs. Goldin. Isn’t that what you told me?”

Josh felt something in himself snap shut against this person in a Venus flytrap way. He had a decision: to soothe this kid or to support his wife.

“A minute ago you tell us one thing,” Josh said, “and now it’s the lower end of the esophagus, which means what? Can we focus on how optimistic you were? You mentioned our son has stabilized. Right? Isn’t that how optimistic?” His plaintive face seemed to ask a different question: Hey, come on. We’re all people here. What are you trying to put us through?

“I’m sorry if I gave a more hopeful impression than the facts warrant,” said Dr. Weiss, who on some basic level still really wanted to seem cool, more straightforward, more the guy he wanted himself to be around Josh: “I just—”

Dori did something Josh had only seen her do in private: a full-body interruption. She shut up Dr. Weiss by turning her back on him.

“Esophageal varices means Zack has chronic liver disease or something,” she said. “It’s a ridiculous thing for them to check for, Josh. He’s an eight-month-old; we would have seen other signs.”

She found the doctor’s eyes again. “You’re going overboard now, and you know it. It’s just so you can say you tracked everything, is what I think.”

To Josh she added: “No, they’re doing tests because they screwed up before. I saw doctors do it all the time. Well, not with my son, doctor.”

She had her shocked sensual look of having blurted out a dirty intimacy. This gave it the flavor of truth.

“We do have to test for these uncommon things, that’s true,” Dr. Weiss said. He sucked in his lower lip; his face got dimples around what had become an angry mouth. “Even what might strike all of us as highly improbable. Now, we have a Pediatrics waiting area, right down the corridor. We’ll make sure to tell you when you can see him. . . .”

Josh kissed Dori as they sat down—to ease his wife’s sadness, and his own. A little peck on her forehead. Her brow had a kind of burned smell, and seemed absolutely hard.

She didn’t respond and Josh, as he sat back, stared at that almost-Elizabethan forehead of hers, which gave Dori her supermodel’s-brainier-sister look. She’d been moody more often lately, sometimes dark moods that had confused him. But maybe that clouded over a memory of something else: Maybe Josh had once, a long time ago, understood that Dori possessed this kind of bravery and firmness; maybe, in the long years of marriage, it had become invisible to him—one of the vanishing acts that habit performs every day, to all familiar things.

WAITING, WAITING. PEOPLE say the Internet has made the world more convenient, but its real effect has been to turn everybody more restless; it’s harder to wait when you’re used to receiving the world at high-speed connection. You feel all things—you feel life itself—should be immediately searchable, quick as desire.

The Pediatrics waiting area was a half-circle of light-blue couches, little desk, bronze reading lamp, plastic flowers in a warmthless vase. All of it spotless, ecumenical, the set of a talk show for two-year-olds.

Sitting with his wife, Josh rested his cheek on her hair, on the pacifying warmth of it. She blew that hair dry every morning, each day being a failed attempt to straighten her mermaid curls: one more relic of their shared life.

He leaned on Dori for a while. He got up to stretch, ankles, back, dismayed neck clicking; he saw, on top of the nearby table, a piece of scrap paper—a printed-out e-mail someone had left (what up kid im so sorry im not around for you but U will beat it lookemia is “BULLSHIT” I am here with marisa who thinks I am SO into nice walks on the beach under the sunset lol . . . truthfully tho, juss wanted to say hope you kick this thing. Hit me back when u can).

Josh thought of the idea of “vigil.” A parent’s job is to protect his children, to do a vigil when the time comes.

Josh had always loved Dori a great deal. More than many of his friends loved their wives, he thought. But like anything man-made, the bond had had its flaws and tiny stress cracks. Even in a lucky relationship, an uncleaned dish may sometimes seem a thrown gauntlet, the sound of someone’s loud-and-clear fuck-you. And of course, in their eight years, the Goldins had not proved immune to parenthood’s hibernal cycles of infrequent sex.

But sometimes the bummer had been smaller, more minor—for instance, Josh’s having to search for that Advil bottle he’d definitely left on his nightstand (Why’s she always moving my shit? he’d wonder). Plus, there had been those recent moods of hers, which she’d only recently started to overcome with the occasional shopping bender.

And yet, he wouldn’t have traded his life and its cushy, glancing, humdrum, fantastic pleasures. And here they were, doing a vigil.

If it was a Saturday with the baby napping, Josh might get a surprise afternoon peek at Dori as she walked, naked, into their bright astonished bedroom—her hips rosy, her hair dark and wet, all postshower sparkle—her breasts staring frankly in the film-set brightness, like two swollen eyes. That was nice: that unintended sex power. (And it turned out that he’d had the bottle of Advil in his pocket all along.) He had been happy, her moods weren’t that bad—had he realized enough how lucky he was?

He leaned his head back to relax, just for a minute, and then he’d begin that vigil.

DORI WOKE HIM at three-thirty A.M. “I need you,” she said.

Dori brushed past Dr. Weiss as she hurried into the Pediatrics ICU with Josh behind her.

“Um . . .” Dr. Weiss said, jogging to catch up—the way a salesperson would scoot to an intruding customer and tell her, sorry, the store’s not quite open yet.

The baby—Josh had reached the baby—the baby lay squirming in a little elevated bed. He was attached to seven inconceivable wires and tubes, yellow, black, two see-through. The baby’s face was pale and drenched in sweat. There were blue pouches under Zack’s open blue eyes. Why are you doing this to me? Is this the way things are, on this planet of yours? said Zack’s sleepy, trustful expression.

“Mr. and Mrs. Goldin, hello again”—a woman’s voice. Josh didn’t turn from the baby to see who this was. A year ago, he and Dori had stood watching an electric shadow on a sonogram, thrilled at a half-finished heart’s little butterfly quiver.

“Hey, kiddo,” Josh said now. He was always Jolly Dad, picking up his crying son, giving a calming Gentle Giant rub to the baby’s back. “Show me a smile, buddy,” the helpless giant said now.

Blue pouches under Zack’s eyes were flecked with dried crud.

Last week, Josh had read in the YouParent Book for Newbies, “It’s no big thing if your one-year-old doesn’t speak yet, as long as s/he responds nonverbally to his/her name, and can follow super-simple instructions.”

“Come on. Look at Daddy.”

With his inadvertent Mohawk hair, his little horizontally creased wrists, Zack was still the same Zack—that perfect-circle head, the nub chin—still kicking his helpless feet; still a beautiful, personality-less aggregate of Josh and Dori’s aspirations, and kind of chubby at twenty-one pounds. But could he follow super-simple instructions, was he responding nonverbally?

“Mrs. Goldin, I suppose I understand your point,” that unfamiliar voice at Josh’s back was saying. “But—”

Through all his baby watching, Josh had missed the on-ramp to the adult conversation. Dori was talking now: “What you’re recommending sounds reasonable and on-the-safe-side, but all I’m saying is if you have to intubate my child for what isn’t really a necessary test.” Her voice, coming up against authority, was guarded: emotion taken by restraint. But neither was she backing down.

“You admitted to me that Zack seemed fine now, is what you just said, right?” She sounded exceptionally rational. “I don’t want you to put him through any invasive procedure needlessly, is all I’m saying here.”

Josh turned to see who his wife was talking to: the black doctor, Dr. Stokes. The woman stood hovering in the little purgatory of the doorway, holding a metal clipboard.

Stop thinking about this woman as black, Josh thought.

“Yes,” Dr. Stokes said, “that’s right”—plodding into the room with her heavy-shod, dogmatic step. “However—”

“You didn’t check his coags,” Josh said. The words just came to him. He had no idea what a coag was, he was mimicking—yes, this was his trait, his quality. This man who’d never considered the possibility of anyone being indifferent to him could add something here; he could gently turn up the bathwater’s heat. “My son came in with bloody vomit. There it is—and you didn’t check coags.”