Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tilted Axis Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In a pink-walled motel, a teenage prostitute brings a grown man to tears. A lovestruck young boy holds the dismembered hand of his crush, only to find himself the object of a complex ménage à trois. A naked body falls from the window of a twenty-storey building, while two female office workers offer each other consolation in the elevator… In these wry and unsettling stories, Prabda Yoon once again illuminates something of the strangeness of modern cultural life in Bangkok. Disarming the reader with surprising charm, intensity and delicious horror, he explores what it means to have a body, and to interact with those of others.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 174

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

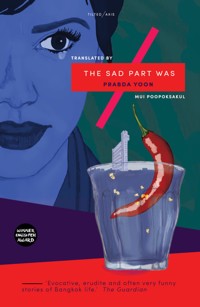

Praise for The Sad Part Was

“The stories that form Prabda Yoon’s mind-bending and strangely melancholic universe are unfailingly provocative… Playful, coolly surrealist... this landmark collection... is not only the first of Yoon’s work to be translated into English, but a rare international publication of Thai fiction... Mui Poopoksakul’s translation renders the stories fluent and accessible, ironing out the linguistic kinks and allowing Yoon’s portraits of Bangkok lives to take centre stage.” — Financial Times

“Evocative, erudite, and often very funny stories of Bangkok life.” — The Guardian

“Very, very clever… A completely fabulous book.”

— Monocle 24: Meet the Writers

“The Sad Part Was is unique in the contemporary literature of Bangkok—it doesn’t feature bar girls, white men, gangsters or scenes redolent of The Hangover Part II. Instead it reveals, sotto voce, the Thai voices that are swept up in their own city’s wild confusion and energy, and it does so obliquely, by a technique of partial revelation always susceptible to tenderness.” — New Statesman

“Young prodigy Yoon’s style seems most influenced by the street-smart, chatty American posse, and revels in all kinds of contemporary twists of the postmodern and meta kind. However its savviness never tips into the sort of self-congratulatory indulgence that many of its western peers suffer from, and it remains charming throughout.”

— The Big Issue

“This trenchant observation of lives in a vibrant, alluring setting, elegantly rendered in English for the first time, definitely raises the bar for Thai literary works to be translated in the future.”

— World Literature Today

“Formally inventive, always surprising and often poignant, with the publication of this fluid and assured translation of The Sad Part Was, Prabda Yoon can take his place alongside the likes of Ben Lerner and Alejandro Zambra as a writer committed to demonstrating that there’s life in the old fiction-dog yet.”

— Adam Biles, author of Feeding Time

“An entrancing and distinctive collection. Yoon’s limpid prose faces up to large, transcendental questions, all the while flickering with beautiful other-worldly images and flashes of deadpan humour.”

— Mahesh Rao, author of One Point Two Billion

“Prabda Yoon is one of Thailand’s finest writers. These witty, adventurous, and wholly brilliant short stories were a necessary shot across the bow when they first appeared in Thai, a deceptively revolutionary collection that helped to transform the country’s literary landscape. Long deemed untranslatable, given their interests in linguistic wordplay, their appearance in English—in this supple, agile translation by Mui Poopoksakul—is a cause for celebration.”

— Rattawut Lapcharoensap

Moving Parts

Part 1: Yucking Finger

“You have one chance to redeem yourself, Maekee.” Ms. Wonchavee’s voice seeped through every fiber of the eleven-year-old’s nerves.

And it even ran to the tip of his tongue, giving the boy with a buzz cut enough of a flavor to know: his teacher’s voice tasted bitter.

Maekee (“His papa’s name’s Maeka. Hahahaha. Maeka came to see Maekee, Teacher lashed them in the heinie, both Maekee and Maeka. Hahahaha.”) pursed his lips so hard that blood was wrung up to the apples of his cheeks. The chalk in his right hand, which hovered over the blackboard, was trembling. He felt trouble brewing in his tummy, and closer to the tail end of that situation—there was no question about it—the area already felt oddly distended, dragging and distressing, as though within seconds the orbs of his butt cheeks were going to blow into pieces.

X to the third power plus Y to the third power equals one hundred fifty-two.

Comma.

X squared Y plus X Y squared equals one hundred twenty.

English letters, numbers, mathematical symbols—these things were ganging up on him with their glares of derision.

Young Maekee’s task was to find the value of X.

Why on earth do you have to find it? Just let X be X. Why is it that when you come across an X, you have to insist on knowing what number it really signifies? Maybe it doesn’t appreciate being an object of public attention.

“Hurry up, Maekee. Your stalling is wasting your classmates’ valuable learning time.”

(“Maek’s a dumb nickname, being called Cloud is lame, his father is to blame. Hahahaha.”)

With a right-handed grip, the boy landed the white, powdery stick on the blackboard. Confusion was blooming and even bearing fruit inside his skull. Everything he had ever learned seemed in that moment to have been snatched up by panic and shuffled and stirred together until chunks of information practically ricocheted off one another inside the two halves of his brain.

Last night I dreamed about a crab… The crab was crawling along the beach. When I grabbed it and sniffed it, it pinched my nose with its right claw. Shocked, I screamed in pain, ouch! And then I hurled the crab into the ocean. It was really angry at me. It refused to be defeated and hurried off to fetch its mother from her hole. The mother was very large, even larger than me. On top of that, she had a human head and looked exactly like my mother. But the crab called her, mother, mother, therefore the mother crab probably wasn’t my mother. The little crab, that tattletale, told its mother that I’d attacked it. I shot back that the little crab attacked me first, but at the end of the day, a mother’s always going to side with her offspring, so the mother crab chose to believe the little crab over me. This being the case, she scowled and threatened to pinch my neck clean through. I tried to negotiate. I said, can’t you pinch some other part? I have a sore throat. But the mother crab didn’t listen and insisted on cutting my throat, so I had to run away. I didn’t get far before I heard my own mother call me:

“Maek, Maek, wake up, sweetie. Otherwise you’re not going to make it to school in time for the national anthem.”

I startled awake, saw that my clock said it was 7:15. Oh no, I’d got up late again. And I hadn’t finished my homework. I still had three questions left.

I bolted into the bathroom, did my business as fast as possible, and then went into the kitchen to look for something to eat. My mother was sitting there pounding some kind of chili paste. I looked up at the clock on the wall. Oh! It was only 6:50… or had I showered back in time? I ran back to look at the clock on my bedside table. It turned out the short hand was still at seven and the long hand at three—it was still 7:15 just like it was earlier. That meant my clock wasn’t working, so I felt a little relieved.

But not very relieved, because, in any case, my homework wasn’t done. And I didn’t know how to do it. That was why I hadn’t finished it in the first place. I have no stomach for Xs and Ys. My mother thought I would be late for school if I took the bus, so she asked Aunt Louie from next door if she could drop me off. I couldn’t complain—I like riding in the back of Aunt Louie’s motorbike. It’s nice and cool, even if the pollution smells bad. Aunt Louie’s nice, too. And her body’s squishy—it’s kind of fun to hold on to. She asked me if I’d finished my homework. I fibbed and said yes. A Buddhist precept broken again, always the same one. But what was I supposed do? It’s what they call a white lie—it doesn’t hurt anybody. When I got to school and ran into Muay, she immediately started running her mouth, making fun of me.

“Maeka came to see Maekee, Teacher lashed them in the heinie, both Maeka and Maekee. Hahahaha.”

Yeah, yeah, laugh.

I asked Piag if I could copy his homework but he wouldn’t let me. Piag’s a prig—he thinks he’s Ms. Wonchavee’s favorite. So I ended up having to make up the answers. As it turned out, they were all wrong. When it was time for Ms. Wonchavee’s class, she asked, “Are you the only dumb one in this class, huh, Maekee? When you’re in class, do you pay attention? Come here. Come to the front of the class, and let’s see you solve this problem.” Then she went about writing an equation on the blackboard. I couldn’t even get my saliva down when I saw the problem—how was I supposed to solve it?

“Now, are you going to make me wait until you’re old enough to have facial hair?” Ms. Wonchavee snapped.

Some of my classmates were snickering through their teeth (“Maekee got spanked, Maekee got kicked. Maeka got tanked and kicked Maekee. Hahaha.”), but they froze as soon as they caught Ms. Wonchavee’s roving eyes of fury.

“Whoever finds this funny will get to suck on a real bitter chunk of giloy,” she promised.

Maekee gulped and then pressed the tip of the chalk on the board and started dragging it.

He took a while scratching shapes out of white powder. Once he was through, what could be read was: X equals one, comma, two.

Maekee thought he was hearing things when he heard a little voice emanating from his finger.

“Yuck.”

The classroom was completely silent. Ms. Wonchavee approached the boy at the blackboard, who was shivering as if he had fever chills.

“Do you think this is the right answer?” she asked in a frosty tone. Instead of acknowledging the question with a verbal reply, Maekee shook his head. “Are you mute, Maekee?” He shook his head again. “There you go, shaking your head again. If this isn’t being mute, then what do you call it? Tell me.”

This time the boy kept his head down and still, not knowing what words to utter.

“Answer me,” Ms. Wonchavee pressed.

“I’m not mute, ma’am.” It cost him a great deal of effort to get the sentence unstuck from the roof of his mouth.

“So, if you’re not mute, tell me if what you have on the blackboard is the correct answer?”

“No, ma’am.” (“Have you finished your homework, Maekee?” “Yes, I already finished it last night.”)

“I gave you a chance to redeem yourself, and you still can’t get it right. What does this mean? Explain it to me. Tell me the reason. Why?”

“I don’t know how to do it, ma’am.” His lips blanched.

Maekee got smacked on the palms with a metal ruler, five times on each hand. (“Count it! Louder!”)

Having received his punishment, Maekee returned to sit at his desk. Although his hands still throbbed from the itchy sting, he’d already put the anxiety, the agony and the embarrassment suffered in front of the blackboard out of his mind.

Then he remembered the strange sound he’d heard, the one that’d leaked out from the tip of his finger.

He put all five fingers of his right hand in front of his face.

Thumb, index finger, middle finger, ring finger, pinky. All five constituents appeared normal.

I must have been hearing things. What kind of finger can make sounds?

Maekee’s assigned desk was situated by the window. What he saw when he looked outside were two large tamarind trees that spread their branches and leaves over a patch of the parking lot.

For several semesters now, he’d used details of the two tamarind trees as resting points for his eyes. They were like air-framed pictures that served as wellsprings of imagination. Whenever he looked out, Maekee didn’t simply see two trees; sometimes he saw monsters, sometimes he saw superheroes, sometimes he saw the face of a certain young lady named Noon (a student in fifth grade, homeroom two, at whom he’d been stealing glances at every opportunity), sometimes he looked out because he wanted to see nothing at all.

Ms. Wonchavee resumed her lesson plan (“Today we’re starting a new chapter. There will be no permission granted to go do any kind of business. Whoever has to go, number one or two, must hold it.”)

As soon as the soundwaves carrying her voice hit Maekee’s ears, he felt as if his yawning reflex had been triggered. His eyelids wanted to sink, his hand wanted to lift up and act as a pillow for his head.

To relieve his drowsiness, Maekee turned toward the window. A light breeze was blowing through the tamarind branches, gently ruffling them.

All of a sudden, his nostrils felt itchy, so he put his right hand in front of his face and wiggled the pinky deep into one of his breathing holes.

When it re-emerged in the outside world, the retracted finger didn’t show up empty-handed but bore a souvenir in the form of a crusty, dark-green nugget.

“Yuck.”

This time Maekee was certain that his finger had cried “yuck.”

That was the day Maekee became acquainted with his yucking finger. To this day, having been familiar with the sound for the better part of his life, he still wasn’t sure which finger it was on his right hand that was the culprit. The thought had crossed his mind that it was the pointer finger, for the sole reason that its name indicated it might be inclined to make a point and state its opinion, but he’d never had any clear proof.

From that moment on, whatever Maekee held or touched appeared to be a source of dissatisfaction for the yucking finger, particularly if the situation involved an important matter in his life. He could trace it back to the instant he held a pencil in his hand while he took his secondary school entrance exam. When he finished the test, the finger made itself heard.

Maekee’s initial theory was that the finger cried “yuck” when it felt that it was partaking in something that would lead his life down a path of failure. But as he grew more familiar with the workings of the yucking finger, he discerned that the key factor in its decision to make noise was, rather, dissatisfaction. As a matter of fact, it had assumed the role of his harshest personal critic.

It’d cried “yuck” when he finished his exam not because it thought he wasn’t going to pass but merely because it didn’t approve of the institution he wanted to attend. It’d cried “yuck” when Maekee located his name as he ran his finger over the list of successful university entrance exam takers, because it didn’t agree with his choice to enroll in the architecture faculty. When he and the then-Miss Piyawon held hands for the first time, the finger cried “yuck” because it felt the two weren’t a sufficiently good match.

It used to cry “yuck” when he composed love letters to the aforementioned Piyawon. It said “yuck” every time he stroked her face lovingly. On their wedding day, the groom heard nothing but “yuck, yuck, yuck, yuck, yuck,” hounding him for almost twenty-four hours.

Maekee worked as an architect, the profession he had always set his heart on (“yuck”). The house into which he and his wife moved and where they shared a life, he’d designed it with his own hands, every line and every corner of it (“yuck”).

Maekee’s decision to take up married life seemed to have been the pivotal step that set the yucking finger off, and it huffed and puffed into a mental state that qualified as lunacy. Its attacks became emotion-driven criticism and out-of-line sarcasm. Maekee would tilt a beer glass for a sip, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d hand over money to pay for fried bananas, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d press the button to call an elevator, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d flip from Channel Seven to Channel Five, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d roll down the car window for some cool air, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d withdraw money from an ATM to buy groceries, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d hit a shuttlecock over the net to victory, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d shake hands with an important client to greet them, and there’d be a “yuck.” He’d drop a one-baht coin into the bowl of a sidewalk beggar, and there’d be a “yuck.”

Whenever he’d bend his wrist and point at his own chest, the finger would cry, “yuck, yuck, yuck, yuck, yuck, yuck.”

“If you’re not happy with what I do, then go inhabit someone else’s body!” Maekee yelled at his own right hand, having reached his limits.

No one else ever heard the “yuck” from his hand. Once, he’d tried to introduce the yucking finger to Piyawon. (“It’s quite a big part of my life, Won. Even though I detest it to the bones, it refuses to go away. It’s at the heart of why I’ve never felt certain about any decision I’ve ever made in life. It kills my self-confidence. Imagine this, Won. No matter what I touch, it starts going, ‘yuck, yuck.’ Yuck, Won—the sound of dissatisfaction, of disgust, of disapproval—with just about every step I take in life. I’m stuck with it. I’ve thought about cutting off all my fingers once and for all, but I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t bear going through with it. All of a sudden—to become a person with a stump for a hand—I couldn’t cope with the idea. It even mocked me then, because I didn’t have the guts to get rid of it. It started going, ‘yuck, yuck,’ even louder than usual. So I’ve learned to live with it instead. I’ve had to train myself to turn a blind eye to it since it’s already a part of me. That’s why, Won, I wanted you to meet it. Here, it’s on my right hand here. Hey, make your yucking noise for Won. Do it, you! Do it! I told you to do it. How is it that on our first night in bed together, you were screaming in a fit all throughout our love-making? Oh, I forgot to tell you. It doesn’t like you very much, Won—it’s been saying ‘yuck’ since we first started dating.”) His wife sat frozen, the disbelief in her ears showing in her eyes.

In that instant, Piyawon’s mind started searching for a new path for her life.

Without her having an inkling, as of yet, of the new life that was going to look for a path out of her belly.

—

The sky was bright and sunny this morning—why then, this afternoon, were the clouds dense and heavy as they dumped water down on the city?

Maekwon, whose nickname was Noom, was annoyed as she sat in her white car, observing the chaos from behind the windshield. The wipers were on medium speed, clearing the way for her eyes with their steady swings so she didn’t have much trouble seeing the scene outside despite the thick curtain of water.

Turning to her right, Noom saw a soggy bunch of city dwellers of various sexes and ages, trying to huddle and squeeze together under the shelter of a bus stop. Some guarded their hairdos with their palms; some had adapted sheets of daily newspapers for use as shields against splashes. The lucky ones who had umbrellas had to share them by default with the strangers next to them, who got to lean on, or under, the former’s good fortune.

The temperature in the car was already cool from the air-conditioning, but the dreary, drippy weather outside lowered it by several degrees more. In unison, the pores along Noom’s body prickled, prompting the fine hairs to stand on edge. Noom gripped the steering wheel tight as if ready at any moment to gun the car to the finish line. But traffic conditions were not cooperating at all: every car on the road had been at a standstill for a good hour.

Noom peeked at the watch on her left wrist. The time was 2:47 in the afternoon, according to its digital numbers.

Her eyes then turned to the mini-clock that came preinstalled in the car: the short hand was at the number two, and the long hand was at around forty-two. When she switched her gaze again to the radio display, the green numbers there said the current time was 2:45 p.m.

In a single location, Noom had three different times to choose to believe.

Regardless of which display she trusted, she was certain that the true time in terms of her life in that present moment—on this earth, in Thailand, in Bangkok, on Silom Road, in the white car, in the flesh-tonedshort-sleeved silk blouse and black pants, in the brown woven-leather shoes, in the navy-blue lace bra and underwear—would probably always elude her.

Even the division of the day into two halves doesn’t offer certainty. Who says the sun inhabits the day and the moon the night? When Noom woke up this morning, the moon was still dangling out in the open, a faint trace in the sky, brazenly fraternizing with the sun. This sort of thing, the sun never does. He doesn’t get carried away by the winds of his mood, lingering around into the hours of darkness. He rises and then he sets, steadfast in the performance of his duties since ancient times, unlike she of the creamy complexion, who sometimes shows up whole, sometimes half, sometimes crescent, sometimes not at all, her fickle and fitful nature inducing the tides to wax and wane along with her.