6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

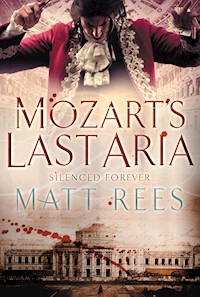

It is 1791 and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is enlightenment Vienna's brightest star. Master of the city's music halls and devoted member of the Austrian Freemason's guild, he stands at the heart of an electric mix of art and music, philosophy and science, politics and intrigue. Six weeks ago, the great composer told his wife he had been poisoned. Yesterday, he died. The city is buzzing with rumours of infidelity, bankruptcy and murder. But Wolfgang's sister Nannerl, returned from the provinces to investigate, will not believe base gossip. Who but a madman would poison such a genius? Yet as she looks closely at what her brother left behind - a handwritten score, a scrap of paper from his journal - Nannerl finds traces of something sinister: the threads of a masonic conspiracy that reach from the gilded ballrooms of Viennese society to the faceless offices of the Prussian secret service. Only when watching Wolfgang's bewitching opera, The Magic Flute, does Nannerl truly understand her beloved brother once again. For, encoded in his final arias, is a subtly crafted blueprint for a radical new tomorrow. Mozart hoped to change his future. Instead he sealed his fate.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

MATT REES was born in Wales and read English at Oxford before moving to the Middle East to become a journalist. He is also the author of the award-winning Omar Yussef series, which follows a detective in Palestine, and is now published in twenty-two countries.

Visit his website at www.mattrees.net

ALSO BY MATT REES

THE OMAR YUSSEF SERIES

The Bethlehem Murders The Saladin Murders The Samaritan’s Secret The Fourth Assassin

MOZART’S LAST ARIA

MATT REES

To Devorah, who is all the music I need.

With thanks to: Dr. Orit Wolf, for showing how great musicians work; Louise and Dieter Hecht, for taking me high above the Karlskirche and demonstrating how scary old Vienna can be; and Maestro Zubin Mehta, who told me that he too would find it hard to live without Mozart.

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Matt Rees 2011

The moral right of Matt Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84887-915-7 (hardback) ISBN: 978-1-84887-916-4 (trade paperback)

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85789-457-1

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Copyright

Map

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1 December 1791 St Gilgen, Near Salzburg

Chapter 2 Vienna

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Epilogue

Author’s Note

The Music

Behind the Book: Mozart’s Last Aria By Matt Rees

MAIN CHARACTERS

Maria Anna “Nannerl” Mozart, sister of the composer

Johann Berchtold, Nannerl’s husband

Karl Gieseke, an actor

Magdalena Hofdemel, Wolfgang’s piano pupil

Baron Konstant von Jacobi, Prussian ambassador to Austria

Leopold II, Emperor of Austria

Prince Karl Lichnowsky, a patron of Wolfgang

Constanze Mozart, Wolfgang’s wife

Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart, Wolfgang’s youngest son

Maria Theresia von Paradies, blind piano virtuoso

Count Johann Pergen, Minister of Police

Emanuel Schikaneder, theatrical impresario, actor

Anton Stadler, musician and friend of Wolfgang

Baron Gottfried van Swieten, head of the Imperial Library and chief of government censorship

Vienna, 1791

In October 1791 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the greatest musical genius the world has ever seen, told his wife he had been poisoned. Six weeks later, at the age of 35, he was dead.

The truth, the truth, even if it be a crime!

The Magic Flute, Act I scene 18

PROLOGUE

When she sang, it was hard to imagine death was so near.

Her maid let me in at my usual time in the mid-afternoon. A soprano voice of considerable purity came from the front of the apartment.

‘Someone’s visiting her, Franziska?’ I asked.

The maid shook her head. ‘She’s alone, sir.’

I passed through the sitting room. She was singing Zerlina’s aria from Don Giovanni, in which the peasant coquette describes the desire beating in her chest. Her voice quietened for the last line, an invitation to the girl’s suitor: ‘Touch me here.’ A raw tone infiltrated as she repeated those words to a crescendo. The concluding note weakened and quavered.

I heard a dry cough as I went through the door to Aunt Nannerl’s bedroom. Her thin hand conducted an imaginary orchestra through the coda.

She laid her fingers on the bedspread and dropped her chin to her chest. Was she hearing the applause of an audience? Perhaps the effort of singing exhausted her.

The lids of her blind old eyes flickered. I pondered the life she had led and all that she had seen, gone now forever. As a musician, I understood the secrets a composer hides in the pages of his score, locked away from those unable to comprehend the fullness of his creation. I had been less perceptive as a nephew, although I was hardly aware of it.

My visits to her home near Salzburg’s cathedral had been so frequent, I would have been tempted to conclude that I knew everything there was of her to be learned. Her renown as a child prodigy on the keyboard, her adolescent performances with my father in Europe’s great cities. Marriage to a provincial functionary and elevation to the minor nobility, so that she had borne the title Baroness of the Empire since 1792. Then after her husband’s passing, her return to Salzburg where she taught piano until her eyesight failed.

This presumption to summarize her seventy-eight years was, in fact, the thoughtless dismissal of an enfeebled old woman by a younger man. I say this with certainty, because today she revealed to me a life more fantastic even than her famous history would suggest.

Her singing done, my aunt lay silent and still in the narrow bed. She wore a lace nightgown and a simple shawl around her shoulders. I kissed her dry cheek, drew up a chair, and recounted the gossip of the town. She didn’t register my presence.

When I grew silent, she reached out, moving with a swiftness that surprised me, and pressed hard on my hand. Her fingers retained the power of a lifetime in which she sat at the piano three hours or more each day, exercising the skills that once entertained kings and princes and counts. ‘Play for me,’ she said.

Her pianoforte was a fine old grand by Stein of Augsburg. I gave her the sonata in A by my father. I wished for her in her frailty to feel roused by the dance rhythm of its Turkish rondo. As I played, she fingered a gold cross inlaid with amber which she wore around her neck. Her blank, sightless eyes were wide. When I finished, she croaked out my name: ‘Wolfgang.’

‘Yes, dearest aunt,’ I replied.

She turned to me as though she had expected someone else to respond.

When I first came to play for her, she told me that I reminded her of my father. In truth my hair and eyes are dark like my mother’s and my talent at the keyboard is of a kind that he would no doubt have described as mechanical. I have nothing of his genius. But I am named Wolfgang, and perhaps for Aunt Nannerl that much resemblance sufficed. Until that moment. I sensed that she spoke directly to the man thirty-eight years dead who had been her little brother. The man famed throughout Europe and even in America as an unmatched composer.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

‘On that shelf. In a box inlaid with mother-of-pearl.’ Her hand lifted from the quilt with an unaccustomed grace that made me wonder if she were already dead and I was gazing upon her spirit, rising free of her fragile bones and decaying skin. I opened the casket and, beneath some old painted ribbons, I found a volume in nicked brown leather. I placed it in her grasp.

‘I’ll be dead soon enough,’ she murmured.

‘May the Lord forbid it, dearest Auntie. Don’t speak of such things.’

She flipped back the book’s cover and ran her fingers over the dry, yellowed pages within. A quill pen such as few have used for years now had filled the book with lines slanting upward from left to right. I recognized the hand as her own, for she had often written to me as I toured the concert halls of Poland and Prussia. She turned a few pages and spread her bony fingers across the text. On the first line, I read a place and a date: Vienna, 21st December 1791.

She shut the book with a clap that was like a cannon shot through the silence of her apartment. In the instant that it took me to blink in fright, the leather-bound volume swung toward me and dropped into my fumbling grasp.

‘Don’t show it to your mother,’ she said.

‘Why not?’ I smiled. ‘What secrets do you keep, Aunt Nannerl?’

Her faint eyebrows lifted and I felt that a much younger woman fixed me with those melancholy brown eyes.

‘Upon my death I shall leave to my son Leopold all that I have,’ she said. ‘He’ll inherit my money, my few valuable pieces of jewelry. Also my papers, my diaries, my daily books. Mostly dull chronicles of the simple routines of Salzburg and the village where I passed my married life.’ She sucked for breath. Her head lapsed against the pillows.

I lifted the volume in my hand. ‘But this—?’

‘Something different. Only for you.’

‘Is it about my father?’ I could ill disguise my eagerness, for I was just a few months old when he was taken from us. He has been with me always at the piano, though only as the mythic gods of Olympus could be said to have been with the Greeks when they ground wheat for flour.

My aunt swallowed hard and coughed. I thought perhaps I had been mistaken. After all, when I used to ask her about my father’s last years in Vienna, she always pleaded that she hadn’t seen him after 1788, when my grandfather’s will was settled in her favor and a coolness arose between the siblings. She had remained with her husband in the village of St Gilgen. My father had continued his career in the opera houses and aristocratic salons of Vienna, until he was cut down three summers later in his thirty-sixth year.

Her lips pursed, she gathered herself. ‘That book records the truth about events that have shaped your life – and all musical history.’

‘It is him,’ I said, striking the notched surface of the leather binding in excitement.

‘It’s his death.’

‘The fever? Yes, Auntie, I know.’

She shook her head. The hair, which her maid had dressed high and old-fashioned even though she lay in bed, rustled across the pillow as if it were hushing me, commanding my silence.

‘His murder,’ she said.

I heard a sound like the final exhalation of a dying soul. I couldn’t tell if it emanated from my aunt or from myself, or perhaps it was the grieving spirit of my poor father. I would’ve spoken, but my breath chilled, my ribs seemed to close in on my lungs and my cravat was suddenly tight around my high collar.

Flicking her wrist in dismissal, Aunt Nannerl subsided onto her pillows.

I hastened to my room in my dear mother’s house on Nonnberg Lane, almost at a run up the steep steps beneath the cliffs. The leather of my aunt’s diary darkened with the sweat of my palm, though the day was cold enough that the first snowfall threatened.

At home, I wiped the perspiration from the cover onto the leg of my breeches, closed my eyes to whisper a Hail Mary for my father’s soul, and opened the book.

Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart Salzburg, October 9 1829

1

DECEMBER 1791 ST GILGEN, NEAR SALZBURG

As I returned from early mass at St Aegidius, snow screened the summit of the Zwölferhorn and layered the village in white silence. Approaching my door through the garden by the lakeside, I heard Little Leopold picking out one of my brother’s minuets on the piano. I smiled that this should be the only sound on the shores of the Abersee that morning. The snowfall smothered all but the essential music that joined me to dear Wolfgang. I wondered if he was watching the same gentle drift cover the streets of Vienna at that moment.

In the hall, Lenerl took my fur and handed me a letter delivered by the village bailiff, who had returned from Salzburg late the previous night. I ordered a hot chocolate and pulled my chair close to the fire in the sitting room. I watched the snow gather in the window mullions, grinning each time the boy struck a false note in the drawing room.

The discordant tune was hardly Little Leopold’s fault. The piano sounded ill enough when I played it. By the mountain lakes of the Salzkammergut, cold and damp had warped the instrument’s wood, made the keys stick, and moldered the hammer casings, so that a true note was rare enough. Even so the boy spent an hour each day at the piano, because he hoped to gratify me.

To tell the truth, it pleased me that my son played only as well as a six-year-old ought. My brother, of course, composed his first dance at six, and it had been my departed father’s desire to recreate that prodigy in my first-born. But that was never my intention. I had come to resent the fact that true happiness was mine only when seated at the piano. Even when playing cards with friends or shooting a pistol at target practice, I moved the fingers of my free hand through an imaginary arpeggio, for if I didn’t I became distracted and irritable. The curse of the artist is to have the best part of one’s faculties occupied only with one’s craft. Friends and family skim your existence like a fisherman on the Abersee, while your real self is as inaccessible to them as the depths of the lake. But I had long since ceased to live the life of an artist, and I sometimes felt this preoccupation rather as a cripple might his useless foot.

I beat a rhythm on the letter lying in my lap. Perhaps it carried news of my brother. In the winter, it was hard to keep up with events beyond the snowbound village. The latest news-sheet to reach us reported that Wolfgang had another original opera in production. Acquaintances returning from Vienna told me that his health wasn’t of the best. He was frequently sick, so I earnestly wished for tidings of his recovery in this letter. I felt sure I recognized the handwriting.

For Madame’s personal attention Madame Maria Anna Berchtold von Sonnenburg Living at the Prefect’s House St Gilgen Near Salzburg

I read my name as if it belonged to a stranger. A collection of surnames, earned by marriage to the man working alone on his accounts in the study across the hall. These things, which ought to have distinguished me, served only to make me anonymous. Before Berchtold had brought me to this remote village – thus adding a geographical anonymity, too – then I had a name that everyone knew and which I admit I still applied to myself in the privacy of these moments seated before the fire.

Mozart.

The memory of that name sounded in my head like a dream. The soft Z and disappearing T with which the French had pronounced it when we entered the salon of Louis XV at Versailles. The long English A I had noted from the mouth of King George’s chamberlain announcing us at Buckingham House.

Lenerl laid my hot chocolate on the table and curtseyed. ‘Will there be anything else, madame?’

I lifted my chin to dismiss her.

It was deluded to muse on my family’s long ago travels to Europe’s capitals. If I no longer bore the name, I had to acknowledge that even then I had been merely a Mozart. Only he had ever been ‘Mozart’. One might have addressed a letter in Milan or Berlin with that single word and it would have found my brother in Vienna. I had inherited the miniature watches and golden snuffboxes, gifts from delighted aristocrats in the time of our joint fame as touring child musicians. But my brother had retained the name.

To the people of this village I wasn’t a Mozart. Few of them had ventured further than Salzburg, six hours’ journey away through the mountains. What could they know of the palaces of Nymphenburg and Schönbrunn where I had displayed my mastery of the keyboard, wandered the gardens, chattered with the king, worn clothes made for the empress’s children? The villagers’ lives didn’t extend beyond the church, the bathhouse where the surgeon pulled their teeth, and the stall by the lake where the sexton sold rosaries and devotional candles.

No one even called me Nannerl any more, now that Mamma and Papa were gone. No one, except he who had been silent for three years. Though it had been unsaid in our last letters, I feared that the unpleasantness of our father’s testament, in which all the fruits of our early fame were bequeathed to me, had broken the bond with my brother, my dear Jack Pudding, my Franz of the Nosebleed.

These years without communication were, I assumed, harder for me to bear than for him. Were he to consider the painful task of writing to his sister in her simple marital home, there would be the distraction of a salon at which to perform, a ball to attend, a concerto to be scored.

I enjoyed no such diversions. Still, I delighted in the reviews of his operas in the Salzburg news-sheets and subscribed to each piano transcription of his works, playing through them with wonder at his compositional development. Even my poor restrained husband had failed to hide his tears when I sang ‘For pity’s sake, my darling, forgive the error of a loving soul’ from Wolfgang’s Così fan tutte. Throughout these years of silence, I comforted myself that one day he might visit our village and we’d play together once more.

I sang that aria as I slipped my finger behind the seal and unfolded the letter. It was from my sister-in-law Constanze.

My song caught at a high G and transformed to a sob.

Your beloved brother passed away in the night of 5th December, she wrote. The greatest of composers and the most devoted of husbands lies in a simple grave in the field of St Marx. My fondest, most desperate wish is to join him there.

Constanze gave the dreadful details. Wolfgang had succumbed to ‘acute heated miliary fever’, which she explained meant that he had been afflicted with a rash resembling tiny white millet grains.

My chin quivered as I read her description of his last days, the swelling of his body, the vomiting and chills, the final coma before his death at one hour past midnight. He had been gone a week.

I crossed myself and mouthed a prayer that he should be delivered to the company of Christ. I pressed the letter to my breast and wept. ‘Wolfgang,’ I whispered.

On the piano, my son stumbled through a French nursery rhyme, ‘Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman’. I had taught it to him one morning after I played Wolfgang’s marvelous set of variations on its theme. The simple melody stabbed at me. I bent over, pain sharp in my abdomen.

The piano went silent. Leopold’s small feet skipped across the hall. He entered the salon with his green jacket buttoned to his chubby chin and blew a kiss at the portrait of Salzburg’s Prince Archbishop on the wall because he knew it made me laugh. When he hugged me I pressed his face to my neck, for in that moment I couldn’t look upon features so like my brother’s had been in his infancy. I stroked his blonde hair behind his ears.

‘Would you play for me, Mamma?’ he said. ‘My fingers are tired.’

‘Tired? And it’s not yet eight in the morning. Will you have no energy to make mischief during the day?’ I grabbed his cold little hands and blew on them.

He giggled. ‘I’m not tired. Just my fingers.’

‘I’ll play for you in a little while, my darling. First, Mamma has a letter to read.’

‘Who wrote it?’

‘Your Aunt Constanze in Vienna.’

Never having met my sister-in-law, the boy shrugged.

‘Go and see if Jeannette is still sleeping,’ I said. ‘It’s time Lenerl gave her breakfast.’

He grinned at the mention of his two-year-old sister and hopped up the stairs.

I closed my eyes. In my mind, I heard ‘Ah, vous dirai-je’ through the dozen complex variations Wolfgang had composed, changes of tempo, legato to staccato, the running scales in the left hand ascending and descending the keyboard. I could feel my own touch light on the keys, see the manuscript, his delicate fingers scribbling the notes across the stave with his characteristic slight backward slant.

Upstairs, Jeanette protested her awakening, until Leopold tickled her into laughter, as he did each day.

I read on through Constanze’s letter. I skimmed the lengthy account of her sister’s desperate errands to priests and doctors, none of whom appeared to have helped my brother. It was far from clear that he had even received the final sacrament.

The letter wound back in time through the premiere of my brother’s new opera The Magic Flute, until I found myself with Constanze and Wolfgang in the public gardens of the Prater on a fine fall day in October. On that occasion, I read, Wolfgang had told his wife that he knew he would ‘not last much longer. I’m sure I’ve been poisoned.’

The cup shook in my grip. Chocolate slopped onto the rug. I laid the cup on the table so hastily that it caught against the saucer and overturned. My fingers smudged cocoa across the letter.

Constanze had been unable to shake Wolfgang from the dire perception that his death was preordained, she wrote. From time to time, he had recovered himself enough to describe his suspicions as temporary fancies. Yet he soon returned to the certainty that his end was coming – at the hands of a poisoner. It grieved Constanze deeply that her last months with Wolfgang should have been marred by this melancholia.

The letter gave a brief account of Wolfgang’s funeral at St Stephen’s Cathedral, organized by his friend, the noted musical connoisseur Baron van Swieten. Constanze closed with a few sentences of condolence, though I sensed that she wished more to impress upon me her extreme suffering and assumed that I’d mourn little for the loss of my estranged brother.

I would have put the letter aside, but I noticed another page folded behind the others. A postscript on a smaller sheet of paper:

It may be that gossip shall reach you asserting your brother’s infidelity to me. I beseech you to place no faith in such slanders. On the day of Wolfgang’s funeral, his dear friend and Masonic brother Hofdemel slashed with a razor at the face of his wife Magdalena, who used to receive lessons from your brother at their house behind Jews’ Square. Poor Hofdemel then took his own life. It has been spoken among some whose shame should be eternal that Hofdemel lost his mind in a fury of jealousy because of a romance between Wolfgang and Magdalena. Some have even asserted that the enraged Hofdemel murdered my beloved Wolfgang by poison. I urge you to reject all such scurrilous conjecture and to know that to his final breath your brother remained a most true and devoted husband and father.

A strange heat flared in my face and darkness crossed my sight. My agitation drove me from my chair. As I came to my feet, the fire crackled in the draughts from my skirt.

I looked into the gilt-framed mirror above the mantel. I saw only death in my pale skin. Wrinkles marked my eyes like the rings of a tree trunk, though signifying the onset of another winter rather than a new spring. Then, there he was, clear in my face, rising out of the image of this woman in the last of her younger days – the wry lips of my brother, his prominent nose and his quiet eyes. He watched me stagger away from the mirror, upsetting the table, smashing the cup of chocolate to the floor.

From his study, I heard my husband clear his throat in annoyance at the noise. I imagined the doctors indulging in the same gesture of impatience when my brother told them that he had been poisoned. He was, after all, someone who always made a fuss about minor injuries and ailments.

Surely Wolfgang had known something they had not. The symptoms may have suggested a ‘miliary fever’, but only to one who didn’t suspect foul play. Could this Hofdemel have been a killer? I forced myself to consider the reprehensible possibility that my brother’s selfishness, cultivated by the indulgence of the many who lauded his genius, may have overridden his moral scruples and led him into the sin of adultery.

As soon as I allowed any credence to the possibility of poison, I was struck by the number of other murderous suspects who occurred to me. Wolfgang never learned to deliver a politic opinion and was often frank and disparaging, so his killer might be a singer he scorned. Or a rival composer robbed of a commission by the greater artist. Then there was his uncouth little wife and her conniving Weber family which had blackmailed my brother into marriage. I found it hard to imagine them as murderers, yet why was Constanze so determined that I should dismiss Wolfgang’s suspicion of poisoning as the delusion of a melancholic spirit?

Everything about Wolfgang’s life was extraordinary. Now I was asked to accept that his death had been so commonplace it could be explained by a doctor’s examination of a rash on his skin. I wouldn’t believe it.

Another glance in the mirror. I couldn’t look away. My eyes, like his, large and brown, a clear hazel. My cheeks, a little marked by pox, though less than Wolfgang’s had been. Were our faces entirely alike? What was solely mine of all these features? Not the mouth, with its thin lower lip and gentle, sardonic upward turn at the corners. That, too, resembled my brother.

As I stared into the glass, I discovered one thing new in this face, something I didn’t recognize as my own characteristic: I found it to be strong. Perhaps it was the same strength that had allowed Wolfgang to defy our father, leaving Salzburg to make his way as an independent composer in Vienna. I had never dared even to imagine that power and certainly hadn’t imitated it. Wolfgang’s defiance had pained me, because I was left alone in our dull provincial town, charged with the care of our father. Yet now I perceived that same boldness in my own gaze.

I crossed the hall, knocked upon the study door, and entered.

My husband turned his thin face toward me and lifted the fur collar of his dressing gown. I read annoyance in his eyes, then he disguised it with the aloofness that greeted petitioners seeking his approval for some official document.

‘My brother has died, may God give him rest.’ I held Constanze’s letter toward him.

‘Surely he was dead to you already.’ He glanced at the chocolate smudge on the paper and raised a single eyebrow. He saw the reproach on my face and cleared his throat. ‘May the good Lord protect his soul, my dear.’ His voice was as thin as his body under the gray velvet of his gown.

‘My sister-in-law writes that he died of a fever last week.’

‘I shall pray for him, of course.’ He waved away the letter and made to return to his papers.

From obedient habit, I stepped backward to the door. The face I had beheld in the mirror stopped me.

I looked my husband over. He had married me so that there would be someone to oversee his household and his five troublesome children. When we wed, my father made it clear that this was my last chance to avoid the lonely life of the old maid. In seven years, I had given Berchtold three more children, though one girl had been lost that spring after only five months. I knew his remoteness to be the reserve of a man never warm who found himself frightened to love me for fear that I should be taken from him like his first two wives. At fifty-five, he was fifteen years my senior, though he saw the marriage as an act of charity on his part toward a spinster from a lower rank of society. Love had been no part of the bargain Papa had struck with Berchtold. Even my virginity had been accorded a monetary value. My dowry was augmented by five hundred florins after the wedding night, when Berchtold had ascertained that he had possessed me intact.

He looked up and took in a loud breath through his nose, exasperated to find me still there. He tapped his hand on the documents before him to signal that he wished to focus on them – perhaps a customs record of iron transported from the mines across the Abersee to Salzburg, or an order for a fornicator to be taken to the torture room in his assistant’s house next door.

I stepped forward.

He righted his periwig and I glimpsed the blue baldness of his scalp beneath.

‘Wolfgang believed he had been poisoned,’ I said.

‘Surely not. Ridiculous man. Over-sensitive.’

‘There may have been intrigues against him. It’s Vienna, after all.’

‘Madam, what do you know of such things?’

‘I haven’t lived all my days in this village, sir. I know the ways of court life and of the cities.’ As my husband, born in the village and educated no further away than Salzburg, did not.

He caught my insinuation and his lips tightened. ‘Let a mass be said for him and be done with it.’

‘I would visit his grave.’

He tapped his bony fingers against his writing desk. ‘I have no time for such a journey. My work here is pressing.’

I knew this for a falsehood. He shut himself into his study not for the perusal of administrative papers, but with the intention of escaping the demands of social life and the expenses incurred by it.

‘I’ll travel alone,’ I said.

‘Alone?’ Surprise disturbed the officious stillness of his face. He was unaccustomed to my determination. In seven years of marriage, I had never pretended to be anything but deferential and far from self-sufficient – behavior promoted to deep habit by my duties during the widower years of my Papa.

‘I’ll take Lenerl to attend to my needs,’ I said.

‘It’s a journey of five days, and expensive.’ He seemed muddled, thwarted and a little desperate, so that I dared wonder if, faced with my departure, he considered that he might miss me.

‘I’ll bear the cost from the bequest of my father. I shan’t burden you.’

‘You never have done so,’ he stammered. His eyes dropped to the floor and his fingers fretted the fur of his collar.

I halted at the door with the handle in my grasp, moved by his emotion. Did all death recall for him his own losses, his wives and infant children? It was cold in the room and I saw that the grate was empty to spare the cost of a fire, though Berchtold had already saved ample funds to provision his children in a lifetime of comfort. ‘Johann,’ I said.

‘I shall wait upon your swift return, madam.’ He shuffled the papers on his desk and straightened. ‘This departure inconveniences me and leaves my children unattended.’

‘I shall make haste to come back to you.’

‘And when you do, we shall hear no more of this brother of yours or of fanciful plots against his life.’

To Berchtold, all professional musicians were alike, disreputable and irresponsible. No doubt he assumed Wolfgang to have died dissolute and alone in a basement tavern. If my brother had been poisoned, surely it would have been to avenge some immorality. Whatever I wished not to countenance, my husband would willingly have suspected.

‘You shall hear no more of such things.’ I shut the door.

In the hall, I called for Lenerl, ordered her to pack my trunks and to send for my husband’s carriage.

When my mother passed away, I fell into a fit of weeping so violent that I vomited and took to my bed for days. My father’s end caused me to drop into a strange darkness from which I didn’t emerge for months. But I was a mother now, a mother who had experienced the loss of one of her own infants and had continued with her life for the sake of the children who remained. I was no longer so feeble before extreme emotions. When I faced Death, I was able to deliberate on which cheek I would strike him. That was how I resolved to go to Vienna.

Seating myself in the drawing room before my piano, a wedding gift from my father, I warmed my fingers under my arms. I looked toward the wall and its simple papering, thin green vertical stripes on white. Beyond it, my husband shivered in the cold and scowled at the documents on his desk. You shall hear this of him, I thought. I played the sonata in A minor Wolfgang wrote after our dear mother’s death in Paris.

Its opening theme, dark and disturbing, sounded true even on my half-ruined keyboard. The D-sharp in the right hand was discordant over the relentless basso ostinato of the left hand, built around the A minor chord. I hammered at the frenetic allegro maestoso as if I wished my brother’s soul to hear it, wherever he was.

‘I’m coming, Wolfgang,’ I whispered.

2

VIENNA

The goddess Providence watched me leave my inn after breakfast and cross the empty Flour Market in the cold wind. In her bronze hands the two-faced head of Janus frowned back upon the past as a bearded old man, while youthful and open he peered the other way into his future. Wishing I might know what lay ahead of me, I shivered. Even the mythic embodiment of foresight could find herself abandoned in a frozen fountain at the center of a blustery square. I prayed that I shouldn’t be so isolated.

Beyond the statue was the gray, shuttered Flour Pit Hall, where Wolfgang often gave concerts, and the terra cotta façade of the Capuchin Church, crypt of the Habsburgs. I kicked at the muck and snowy slush with my high boots, and headed in the direction of the younger Janus’s gaze.

The innkeeper had directed me toward a narrow street of five-story houses, their ground floors in heavy, broad granite and their gables stuccoed orange or yellow or white. The buildings were bright, despite the dull, flat light filtering through the clouds. When I came to the foot of a church spire on my left, I turned into Rauhenstein Lane and looked for my brother’s home.

A gentleman in a broad-brimmed English hat was kind enough to guide me into a modest courtyard. Horse feed and wet hay ripened on the cold air.