9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

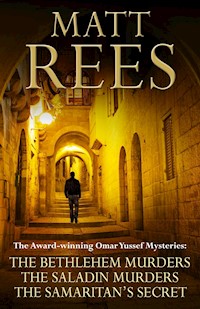

Three acclaimed novels in the Omar Yussef series in one volume, from an award-winning author. The Bethlehem Murders For decades, Omar Yussef has taught history to the children of Bethlehem. When a favourite former pupil, George Saba, is arrested for collaborating with the Israelis in the killing of a Palestinian guerrilla, Yussef is convinced that he has been framed and sets out to prove his innocence. The Saladin Murders When Omar Yussef learns that a fellow teacher has been accused of links to the CIA, and jailed, his suspicions are immediately aroused. The more Yussef investigates the arrest, the more people seem to be implicated, and the murkier his search for the truth becomes. The Samaritan's Secret When Omar Yussef travels to Nablus, the West Bank's most violent town, to attend a wedding, he little expects the trouble that awaits him. An ancient Torah scroll belonging to the Samaritans, descendants of the biblical Joseph, has been stolen. But when the dead body of a young Samaritan is discovered, a seemingly straightforward theft inquiry takes an unexpected turn.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

THE BETHLEHEM MURDERS

THE SALADIN MURDERS

THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET

Matt Rees was born in Wales and read English at Oxford before moving to the Middle East to become a journalist. He is also the author of the award-winning Omar Yussef series, which follows a detective in Palestine, and is now published in twenty-four countries.

Visit his website at www.mattrees.net

Published in E-book in Great Britain in 2013 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Matt Rees 2007, 2008, 2009

The moral right of Matt Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The novels in this anthology are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 157 9

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

The Bethlehem Murders

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

The Saladin Murders

Cover

The Saladin Murders

Also by Matt Rees

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

The Samaritan’s Secret

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

First published in the United States in 2006 by Soho Press, Inc., 853 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

© Matt Rees 2006

The moral right of Matt Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84354 592 7 Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 84354 625 2 eISBN 978 0 85789 525 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd. Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

To Bo

All the crimes in this book are based on real events in Bethlehem. Though identities and some circumstances have been changed, the killers really killed this way, and those who died are dead just the same.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 1

Omar Yussef, a teacher of history to the unhappy children of Dehaisha refugee camp, shuffled stiffly up the meandering road, past the gray, stone homes built in the time of the Turks on the edge of Beit Jala. He paused in the strong evening wind, took a comb from the top pocket of his tweed jacket, and tried to tame the strands of white hair with which he covered his baldness. He glanced down at his maroon loafers in the orange flicker of the buzzing street lamp and tutted at the dust that clung to them as he tripped along the uneven roadside, away from Bethlehem.

In the darkness at the corner of the next alley, a gunman coughed and expectorated. The gob of sputum landed at the border of the light and the gloom, as though the man intended for Omar Yussef to see it. He resisted the urge to scold the sentry for his vulgarity, as he would have one of his pupils at the United Nations Relief and Works Agency Girls School. The young thug, though obscured by the night, formed an outline clear as the sun to Omar Yussef, who knew that obscenities were this shadow’s trade. Omar Yussef gave his windblown hair a last hopeless stroke with a slightly shaky hand. Another regretful look at his shoes, and he stepped into the dark.

Where the road reached a small square, Omar Yussef stopped to catch his breath. Across the street was the Greek Orthodox Club. Windows pierced the deep stone walls, tall and mullioned, capped with an arch and carved around with concentric rings receding into the thickness of the wall, just high enough to be impossible to look through, as though the building should double as a fortress. The arch above the door was filled with a tympanum stone. Inside, the restaurant was silent and dim. The scattered wall-lamps diffused their egg-yolk radiance into the high vaults of the ceiling and washed the red checkered tablecloths in a pale honey yellow. There was only one diner, at a corner table below an old portrait of the village’s long-dead dignitaries wearing their fezes and staring with the empty eyes of early photography. Omar Yussef nodded to the listless waiter—who half rose from his seat—gesturing that he should stay where he was, and headed to the table occupied by George Saba.

“Did you have any trouble with the Martyrs Brigades sentries on the way up here, Abu Ramiz?” Saba asked. He used the unique mixture of respect and familiarity connoted by calling a man Abu—father of—and joining it to the name of his eldest son.

“Just one bastard who nearly spat on my shoe,” said Omar Yussef. He smiled, grimly. “But no one played the big hero with me tonight. In fact, there didn’t seem to be many of them around.”

“That’s bad. It means they expect trouble.” George laughed. “You know that those great fighters for the freedom of the Palestinian people are always the first to get out of here when the Israelis come.”

George Saba was in his mid-thirties. He was as big, unkempt and clumsy as Omar Yussef was small, neat and precise. His thick hair was striped white around the temples and it sprayed above his strong, broad brow like the crest of a stormy wave crashing against a rock. It was cold in the restaurant and he wore a thick plaid shirt and an old blue anorak with its zipper pulled down to his full belly. Omar Yussef took pride in this former pupil, one of the first he had ever taught. Not because George was particularly successful in life, but rather for his honesty and his choice of a career that utilized what he had learned in Omar Yussef’s history class: George Saba dealt in antiques. He bought the detritus of a better time, as he saw it, and coaxed Arab and Persian wood back to its original warm gleam, replaced the missing tesserae in Syrian mother-of-pearl designs, and sold them mostly to Israelis passing his shop near the bypass road to the settlements.

“I was reading a little today in that lovely old Bible you gave me, Abu Ramiz,” George Saba said.

“Ah, it’s a beautiful book,” Omar Yussef said.

They shared a smile. Before Omar Yussef moved to the UN school, he had taught at the academy run by the Frères of St. John de la Salle in Bethlehem. It was there that George Saba had been one of his finest pupils. When he passed his baccalaureate, Omar Yussef had given him a Bible bound in dimpled black leather. It had been a gift to Omar Yussef’s dear father from a priest in Jerusalem back in the time of the Ottoman Empire. The Bible, which was in an Arabic translation, was old even then. Omar Yussef’s father had befriended the priest one day at the home of a Turkish bey. At that time, there was nothing strange or blameworthy in a close acquaintance between a Roman Catholic priest from the patriarchate near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem and the Muslim mukhtar of a village surrounded by olive groves south of the city. By the time Omar Yussef gave the Bible to George Saba, Muslims and Christians lived more separately, and a little hatefully.

Now, it was even worse.

“It’s not the religious message, you see. God knows, if there were no Bible and no Koran, how much happier would our troubled little town be? If the famous star had shone for the wise men above, let’s say, Baghdad instead of Bethlehem, life would be much brighter here,” Saba said. “It’s only that this Bible in particular makes me think of all that you did for me.”

Omar Yussef poured himself some mineral water from a tall plastic bottle. His dark brown eyes were glassy with sudden emotion. The past came upon him and touched him deeply: this aged Bible and the learned hands that left the grease and sweat and reverence of their fingertips on the thin paper of its dignified pages; the memory of his own dear father who was thirty years gone; and this boy whom he had helped shape into the man before him. He looked up fondly and, as George Saba ordered a mezze of salads and a mixed grill, he surreptitiously wiped his eyes with a fingertip.

They ate in quiet companionship until the meat was gone and a plate of baklava finished. The waiter brought tea for George and a small cup of coffee, bitter and thick, for Omar.

“When I emigrated to Chile, I kept the Bible you gave me close always,” George said.

The Christians of George’s village, Beit Jala, had followed an early set of emigrants to Chile and built a large community. The comfort in which their relatives in Santiago lived, worshipping as part of the majority religion, was an ever-increasing draw to those left behind, sensing the growing detestation among Muslims for their faith.

In Santiago, George had sold furniture that he imported from a cousin who owned a workshop by the Bab Touma in Damascus: ingeniously compact games tables with boards for backgammon and chess, and a green baize for cards; great inlaid writing desks for the country’s new wine moguls; and plaques decorated with the Arabic and Spanish words for peace. In Chile, he married Sofia, daughter of another Palestinian Christian. She was happy there, but George missed his old father, Habib, and gradually he persuaded Sofia that now there was peace in Beit Jala and they could return. He admitted that he was wrong about the peace, but was glad to be back anyway. He had seen Omar Yussef here and there since he had brought his family home, but this was their first chance to sit alone and talk.

“The old house is the same as ever, filled with racks of Dad’s wedding dresses. The rentals in the living room and those for sale in his bedroom, all wrapped in plastic,” George Saba said. “But now they’re almost crowded out by my antique sideboards from Syria and elaborate old mirrors that don’t seem to sell.”

“Mirrors? Are you surprised that no one should be able to look themselves in the eye these days?” Omar Yussef sat forward in his chair and gave his choking, cynical laugh. “They lead us further into corruption and violence every day, and no one can do anything about it. The town is run by a shitty tribe of uneducated bastards who’ve got the police scared of them.”

George Saba spoke quietly. “You know, I’ve been thinking about that. The Martyrs Brigades, they come up here and shoot across the valley at Gilo, and the Israelis fire back and then come in with their tanks. My house has been hit a few times, when the bastards did their shooting from my roof and drew the Israeli fire. I found a bullet in my kitchen wall that came in the salon window, went through a thick wooden door and traveled down a hallway, before it made a big hole in my refrigerator.” He looked down and Omar Yussef saw his jaw stiffen. “I won’t let them do it again.”

“Be careful, George.” Omar Yussef put his hand on the knuckles of George Saba’s thick fingers. “I can say what I feel about the Martyrs Brigades, because I have a big clan here. They wouldn’t threaten me, unless they were prepared to face the anger of half of Dehaisha. But you, George, you’re a Christian. You don’t have the same protection.”

“Maybe I’ve lived too long away from here to accept things.” He glanced up at Omar Yussef. There was a raw intensity in his blue eyes. “Perhaps I just can’t forget what you taught me about living a principled life.”

Omar Yussef was silent. He finished his coffee.

“You know who else has returned to Bethlehem from our old crowd?” George Saba’s voice sounded tight, straining to lighten the tone of the conversation. “Elias Bishara.”

“Really?” Omar Yussef smiled.

“You haven’t seen him yet? Well, he’s only been back a week. I’m sure he’ll stop by your house once he’s settled in.”

Younger than George Saba, Elias Bishara was another of Omar Yussef’s favorite pupils at his old school. “Wasn’t he studying for a doctorate in the Vatican?” Omar Yussef asked.

“Yes, but since then he’s been living in Rome as some kind of apostolic secretary to one of the cardinals. Now he’s back at the Church of the Nativity. I know, Elias and I are only asking for trouble by coming home, Abu Ramiz. Perhaps you can’t understand what it has been like for us. We grow up in this dismal place, wanting desperately to leave for another country where we can make money and live in peace. But the day always comes when you imagine the savor of real hummus and the intoxicating brightness of the sun on the hills and the sound of the church bells and the muezzins. You miss it so much you can taste the longing on your tongue. Then you come back, no matter what it is you are giving up. You just can’t help it.”

“I’ll go to the Church and say hello to Elias as soon as I get a chance.”

“Next month is Christmas, so I wanted to invite you to come with us to the Church to celebrate,” George said. “And then you and Umm Ramiz will come for Christmas dinner at my house.”

“I would be delighted, and so will she, too.”

The two men argued over who should pay the check. Both threw money onto the table and picked up the other’s cash to force it back into his hand. Then the shooting began. It was close enough that it sounded big and hollow, not like the whipcrack of faraway firing.

George looked up. “Those sons of whores, they’ve started again.” He stood, leaving his cash on the table. “Abu Ramiz, I have to go.”

They went to the door. Omar Yussef could see the tracer striping across the valley toward a house along the street. The big, bass bursts of gunfire from the village were directed toward the Israelis in the Jerusalem suburb over the wadi. The gunfire emanated from the roof of a square, two-story house only fifty yards away. There was a dark Mitsubishi jeep in the lee of the building. George Saba stepped into the street. “Jesus, I think they might be on my roof again.”

“George . . .”

“Don’t worry about me. Get out of here before the Israelis come. Not even your big clan will protect you from them. Goodbye, Abu Ramiz.” George Saba put an affectionate hand on Omar Yussef’s arm, then went fast along the street, bending low behind the cover of the garden walls.

Omar Yussef put his hands over his ears as the Israelis switched to a heavier gun. It shot tracers that left a deceptively slow, dotted line in the darkness, like a murderous Morse Code. That code spelled death, and the warmth that he had felt during the dinner left Omar Yussef. He could no longer see George Saba. He wondered if he should follow him. The waiter stood nervously behind him in the doorway, eager to lock up. “Are you coming inside, uncle?”

“I’m going home. Good night.”

“May God protect you.”

Omar Yussef thought he must have looked foolish, groping his way along the wall at the roadside, kicking his loafers in front of him with every step to be sure of his footing on the broken pavement. An awareness of fear and doubt came over him. He sensed movement in the alleys he passed, and shadows momentarily took on the shape of men and animals, as though he were a frightened child trying to find the bathroom in the darkness of a nighttime house. He was sweating and, where the perspiration gathered in his moustache and on the baldness of his head, the night wind chilled him. What an old fool you are, he told himself, scrambling about in a battle zone in your nice shoes. Sometimes you can have a gun to your head and you still don’t know where your brains are.

The firing behind him grew more intense. He wondered what George Saba might do if he found the gunmen on his own roof again, and he decided that only when a gun points at your heart do you realize what it is that you truly love.

George Saba’s family huddled against the thick, stone wall of his bedroom. It was the side of the house farthest from the guns. George came though the front door. The shooting was louder inside and he realized the bullets were punching through the windows into his apartment. He ducked into an alcove in the corridor and crouched against the wall. At the back of the house, his living room faced the deep wadi. It was taking heavy fire from the Israeli position over the canyon.

Sofia Saba stared frantically across the corridor at her husband. She was not quite forty, but there were lines that seemed suddenly to have appeared on her face that her husband had never noticed before, as though the bullets were cracking the surface of her skin like a pane of glass. Her hair, a rich deep auburn dye, was a wild frame for her panicked eyes. She held her son and daughter, one on either side of her, their heads grasped protectively beneath her arms. All three were shaking. Next to them, Habib Saba sat silent and angry, below the antique guns mounted decoratively on the wall by his son. His cheekbones were high and his nose long and straight, like an ancient cameo of some impassive noble. Despite the gunfire, he held his head steady as an image carved from stone. George called out to his father above the hammering of the bullets on the walls, but the old man didn’t move.

Most of the Israeli rounds struck the outside wall of the living room with the deep impact of a straight hit. These were no ricochets. Every few moments, a bullet would rip through the shattered remains of the windows, cross the salon and embed itself in the wall behind which George Saba’s family sheltered. Sofia shuddered with each new impact, as though the projectiles might take down the entire wall, picking it away chunk by chunk, until it left her children exposed to the gunfire. The hideous racket of the bullets was punctuated by the sounds of mirrors and furniture falling in the living room and porcelain dropping to the stone floor from shattered shelves.

A bullet rang down the corridor and splintered the wood of the front door through which George Saba had entered. As he had dodged along the road in the darkness, he had been determined that tonight he would act. He had cursed the gunmen under his breath, and when a shot struck particularly close to him he had sworn at the top of his voice. Now he wanted only to crawl deeper into the alcove, to dig himself inside the wall until this nightmare stopped. If he stayed in the niche long enough, perhaps he would awake and find himself in his store in Santiago and this idiotic fantasy of returning to his childhood home would once more be merely a dream, not a reality of red-hot lead, blasting through his home, destructive and deadly. He looked over to the bedroom and caught his wife’s pleading expression, as she struggled to keep the heads of their children hidden beneath her arms. He wasn’t going to wake up in Chile. He couldn’t hide. He had to end this. He got to his feet, sliding up the wall, pushing his back hard against it as though it might wrap his flesh in impenetrable stone. He took the tense, expectant breath of a man dropping into freezing water and dashed across the exposed corridor into the bedroom.

George Saba hugged his wife and children to him. “It’s going to be all right, darlings,” he said. “I’m going to take care of it.” He pulled them close so they wouldn’t see that his jaw shook.

For the first time, his father moved his head. “What are you going to do?”

George looked sadly at the old man. He wasn’t fooled by the stillness with which Habib Saba held himself. It wasn’t calm and resolve that kept the old man frozen in his self-contained posture against the wall. His father cowered in the bedroom because he was accustomed to the corruption and violence of their town. He lived as quietly and invisibly as he could, because Christians were a minority in Bethlehem, and so Habib Saba was careful not to upset the Muslims by standing up to them. George had learned a different way of life during his years away from Palestine. He put his hand on his father’s shoulder and then touched the old man’s rough cheek.

Quickly, George stood and reached for an antique revolver mounted on the wall. It was a British Webley VI from the Second World War that he had bought a few months before from the family of an old man who had once served in the Jordanian Arab Legion and kept the gun as a souvenir of his English officers. The gray metal was dull and there was rust on the hinge, so that the cylinder couldn’t be opened. But in the darkness its six-inch barrel would look deadly enough, unlike the three inlaid Turkish flintlocks that decorated the bedroom wall beside it. George Saba tightened his hand around the square-cut grip and felt the gun’s weight.

Habib reached out for his son’s arm, but couldn’t hold fast. Sofia screamed when she saw the revolver in her husband’s hand. At the sound, her daughter peered from under her mother’s arm. George knew he must act now or the sight of those frightened eyes would break him. He reached down and put his hand over the child’s brow, as though to close her eyes. “Don’t worry, little Miral. Daddy’s going to tell the men to stop playing and making noise.” It sounded stupid and, for the moment, he kept his fingers over the girl’s face so that he wouldn’t see the look of incredulity he felt sure would have registered on her features. Even a child could tell this was no game. Then he dashed through the front door.

Chapter 2

Darkness smothered the valley swiftly, sliding gray down the steep hillsides, blotting out the scanty olive trees and shading the romantic portraits of the martyrs in the cemetery, until it settled over the village of Irtas. In the home of the Abdel Rahmans, no one turned on the lights. To do so would have illuminated the vegetable patch and the glade of pines outside, through which the family expected their eldest son to creep home soon for the iftar, the evening meal to break the Ramadan fast. In the front room of the house, Dima Abdel Rahman set down a tray of kamar al-din. She placed the glasses of apricot juice before the cushions where each member of the family would sit to eat. The glass with the most fruit floating in it, she put by the corner of the low table, where Louai would want to sit so that he could watch the windows for any threat. Then she went to the open window for a moment and, ignoring the excited, fluttery calls of her mother-in-law from the kitchen, strained her eyes into the shadows for a sight of her husband. She adjusted her cream headscarf, which curved to a pin below her chin and emphasized the strong oval of her face. Her eyes were a light, warm brown, like the foliage of Palestine’s brief autumn, and her lashes were long. It was a kindly, confident face, though it was tainted by an undertone of recent loneliness and an anxious tightness about her lips. She shivered and hugged herself as the night’s chill penetrated her bright holiday robe.

The building was well situated for these clandestine visits. Louai Abdel Rahman could move from his hideout in Irtas to this square two-story house a quarter of a mile along the valley without stepping into the open, where Israeli hit squads might see him. The cinderblock homes and winding streets of Irtas billowed across the lowest slopes and into the narrow bottom, looking from this end of the valley like rushing rapids washing through a crevasse, foaming against the precipices and cresting on fingers of easier gradients. At the edge of the village, the valley was a fertile place, the green plots of the fellahins spraying out around the famous gardens of the Roman Catholic convent tended by the Sisters of the Hortus Conclusus. Behind the Abdel Rahman house at the head of the valley were the ancient wells known as Solomon’s Pools, which fed the main aqueduct of Herod’s Jerusalem. With springs across the vale, the people of Irtas allowed themselves a luxury barred to other rural Palestinians, who strained to eke out the fetid contents of their cisterns through the eight dry months of summer: in Irtas there were tall, shady pine trees, as well as the squat, functional olives to which most villages were limited. Dima Abdel Rahman knew her husband could move about, hidden beneath the canopy of leaves, as though nature wished to be complicit in his struggle against the occupation. If the Israelis watched from above, Louai would surely see them, because the thick vegetation thinned and petered out as the hillsides cut up from the narrow floor of the wadi. The soldiers would be exposed on those bare slopes, even in the twilight.

Then Dima Abdel Rahman heard sounds among the trees. It must be him, she thought. She kept quiet, even though her mother-in-law called her to help with the serving once more. There was nothing moving that she could see, but the undergrowth crackled beneath careful footsteps. He was coming, for the first time in weeks. She straightened her headscarf excitedly once more and fiddled with the pin beneath her throat.

No matter how long Louai hid from the Israelis, she would never grow accustomed to the absences between his visits to the house where she lived with his parents, his brother and three sisters. They had been married only a year, but he had been underground most of that time. It was as her parents had feared. Before the wedding, they had consulted with their neighbor, ustaz Omar Yussef, a respected friend of her father and a schoolteacher who took a special interest in her. He had told Dima’s father that, though there was a risk the girl soon would be widowed, there seemed to be love between the two young people and such feelings ought to be nurtured in these days of hate.

So Dima had given up her studies at the UNRWA Girls School in Dehaisha to marry Louai. She went to work in her father-in-law’s autoshop, doing the accounts and answering the phones. At home she ended up doing the family’s housework and dreaming of Louai’s rare homecomings. It became a week or longer between his visits to the house, and each time he spent only an hour or two with her before he had to be gone once more. When he wasn’t there, she was melancholy. Without her husband to enliven her nights, the days in the glass booth at the back of the garage were dull. Worse, Louai’s father Muhammad and his brother Yunis grew cold toward her, as though they blamed her for the risks he took in coming through the darkness to the house. Or maybe it was something else.

Weeks before, a burly man in military fatigues had come into the autoshop when Muhammad and Yunis were out. He sat on Dima’s desk, crumpling her paperwork with his broad backside, and tried to touch her cheek. “I have something I need to buy from your family,” he said to her, “but I’d pay double the price if they’d let you deliver it to me.” She moved away and the man laughed. Behind him, she noticed Yunis at the entrance to the garage. The man lifted his hand again, but then followed her eyes to her brother-in-law. He laughed again and left the autoshop. Yunis looked darkly at her and followed the man out, whispering insistently to him. He had barely spoken to her since that day.

When Louai last came home, Dima complained that his father and brother were distant with her. A quiet, calm man, he surprised her with his sudden anger. “You have no right to judge my father and brother,” he shouted. “These are not matters that concern you.”

Dima had no idea what “matters” he meant—she had referred only to their icy manner about the house and office. But Louai quickly calmed himself and apologized. He said he was tense because of his confinement in a safehouse, but Dima knew he was lying. He was defensive, because he, too, was frustrated with his brother. Dima’s suspicions about Yunis somehow were confirmed by Louai’s outburst. Before he had left that last time, Dima had heard Louai and Yunis arguing. They had spoken in whispers. She couldn’t tell what they were saying, but the tone had been heated. She had also noticed her husband stare sternly at his father after he embraced him in farewell.

As Dima Abdel Rahman stood at the window straining to see the source of the steps sounding in the undergrowth, she heard the steady footfalls stop. Then they began again, not so clearly defined, but rather a shuffle through the underbrush, as though the creeping man had suddenly relaxed.

“Oh, it’s you, Abu Walid.”

It was her husband’s voice. He spoke calmly, in a friendly tone. Dima looked toward the voice. For a moment she saw nothing, then at the edge of the pines a small red dot appeared, flitting unsteadily as though describing a circle of a small radius. It quivered to a halt, like a firefly settling onto a leaf. When the red dot was still, instantly there was a shot. Dima gasped, and it was as though the sudden extra oxygen fed her eyes, because she saw Louai. He stumbled from the edge of the trees. Dima couldn’t make out his face, but she knew the denim jacket and the jeans she had bought for him before his last visit. His hand clutched his shoulder.

The red dot, again. Another shot cracked out of the darkness and Louai spun, his arms stretched wide, like a Sufi dancing in the divine trance of the sema, whirling, head back, one hand turned toward the earth, the other palm heavenward. He collapsed facedown in the cabbage patch.

Dima stared. Her mother-in-law came wailing into the room, crying out that the Israelis were invading. “They will murder us all,” she called. “Yunis, my son, come and bring your father to protect us. Muhammad, come to protect us, husband.” There were footsteps from the upper floor as the men awoke from their evening naps and hurried to the stairs. Dima felt as if she had been turned to stone. If she moved, she thought she might fall to pieces on the ground, her body dropping noisily in a cloud of dusty chips. With a fearful effort, she turned and ran to the door, knocking over a glass of kamar al-din on the way.

The killers could be out here still, Dima thought, but I have to reach him and touch him. Don’t let him be badly hurt.

She stumbled through the cabbages and dropped to the ground at Louai’s side. It was then that she realized she was sobbing and, as she turned her husband onto his back, her sobs became a scream. His wide eyes were blank and stared right through her. His tongue protruded palely between his lips. The denim jacket was wet, saturated with blood from the collarbone to the navel. Dima held his hand and touched his face. He was so beautiful. She looked at his hand. His fingers were long and slim, these fingers that touched her delicately when he came to the house. Why was the cause of Palestine worth more to him than their happiness and their love?

Louai’s mother came through the cabbages. She knew the meaning of Dima’s scream. She fell on her knees at her boy’s side and laid her hands on the bloody torso. Dima heard the soft squelching of the wet denim as the old woman gripped it desperately. The mother lifted her hands, covered her cheeks in her son’s blood and called out to God.

“Get away from him.”

Dima heard Yunis behind her. He grabbed her shoulder and shoved her away from her husband’s corpse. He lifted his mother gently, but led her away from the body, too. She sobbed and cried, “Allahu akbar,” God is most great. As he passed Dima with his mother, Yunis caught her eye. His look was defensive and hostile. The glance confused her. Yunis looked away. “Don’t disturb anything. Leave the place for the police to investigate,” he said.

“The police?”

“Yes.”

“What is there for the police to investigate? The Israelis assassinated your brother. Are the police going to go and arrest the Israeli soldier who fired the shots?”

“Just do as I say.”

“The police will be useless unless a Palestinian did this. What Palestinian would kill a member of our family? What Palestinian would kill a leader of the resistance?”

Yunis averted his eyes. Dima stepped toward him, but he turned his gaze on her again and it was reproachful and violent.

Dima would have spoken more angrily, if it had not seemed like a desecration of her husband’s body to use harsh words. When Yunis turned on the lights in the house, beams of fluorescent blue filtered outside. Their icy reflections shone in the pool of Louai’s blood.

Chapter 3

Omar Yussef placed his purple leather briefcase carefully on his desk and opened the shiny gold combination locks. He unclipped a Mont Blanc fountain pen from the pocket on the inside of the lid. It was a present from a graduating class of students, who knew that he loved stylish things. He felt the pleasing weight and balance of the Mont Blanc in his hand and glanced at the pile of exercise books on his desk to be graded. He wondered if the class whose books lay before him would ever feel generous or grateful toward their teacher. He began to read through their short essays on the demise of the Ottoman Empire. He spent a great deal of his time, too much of it, angry with these children. He tried not to be, but he couldn’t stand to listen to them when they rolled through the political clichés of the poor, victimized Arab nation, subjugated by everyone from the Crusaders and the Mongols to the Turks and the British, all the way to the intifada. It wasn’t wrong to see the Arabs as victims of a harsh history, but it was a mistake to assume that they bore no responsibility for their own sufferings. In his classroom, Omar Yussef would step in and destroy their hateful, blind slogans. Yet he could see that it only made him angrier and left the students somehow mistrustful of him.

Omar wrote a “C” grade in the margin of the first messy notebook, because he decided to be generous, and opened another. He was getting old. He thought of George Saba and the comforting feeling he experienced as they dined, that this pupil and others like him would be the proud legacy of Omar Yussef. He knew that his recent irritable outbursts in the classroom were caused by a combination of frustration at the ignorant, simple-minded, violent politics of his students and the sense that he was already too old, too distant from their world ever to change them. He knew it would be worse in a boys school, but there was such violence even in his girls that it shocked him. No matter how he tried to liberate the minds of Dehaisha’s children, there were always many others working still more diligently to enslave them.

It was different when he taught at the Frères School. During those years, there were many fine young minds that had opened themselves to him. It wasn’t just the pupils that had changed. Tension and hatred had engulfed Bethlehem, and on their heels came poverty and resentment and propaganda. Even a fine pupil like Dima Abdel Rahman was sucked into the violence. Her father, Omar Yussef’s neighbor, had called the previous night to tell him about the death of the girl’s husband, Louai Abdel Rahman. The funeral would be in the early morning, when Omar Yussef was at work, but he planned to visit Dima Abdel Rahman in the afternoon. He had thought he might suggest that she return to her studies, but then he remembered that she truly loved her husband and he decided to wait before offering her any such proposals for her future.

It was at times like these, when the first light of the day was crisp in his empty classroom and the essays he graded were sub-par, that Omar Yussef wondered if he ought not to accede to the request of the school’s American director and quit. Omar Yussef was only fifty-six years old, but Christopher Steadman wanted him to retire. He saw how the American looked at his shaking hands, reminders of the years of alcohol that were now behind him. They made him seem even more fragile than his slow, labored walk. Maybe Steadman only wanted a more vigorous man, but Omar Yussef hated him because he suspected the American really wanted a teacher who wouldn’t talk back. Omar Yussef reflected that he had molded a sufficient number of fine young minds, like those of George Saba, Elias Bishara and Dima Abdel Rahman, enough to satisfy the most conscientious of teachers. Perhaps he shouldn’t be driving himself crazy, putting his heart through the stress of confronting the entire machine of mad martyrdom propaganda and lies every day.

The first of his pupils entered. “Morning of joy, ustaz.”

Omar Yussef returned the greeting, quietly. With the student’s arrival, the comforting thoughts of his old pupils dissolved and he dropped back into the alien present, his senses heightened to the tawdriness of the school. The chairs scraped on the classroom floor as the girls seated themselves. The air filled with the background stink of unwashed armpits and bean farts. Omar Yussef looked down at the exercise book and pretended to be grading it. The pen shook in his fingers, as it always did these days. There was a tiny liver spot on the back of his hand, which presented itself to him as he turned the pages. It was new, appearing almost overnight, as though some genie had stolen into his bedroom while he slept and stamped him ineradicably as prematurely aged. When he thought of it that way, he wondered that the visiting spirit found him in his bed and asleep, for it seemed to Omar Yussef that he spent half the night urinating and the genie could just as easily have impressed its seal of superannuation on his dribbling penis. This was the real him and this was the reality of his life. Maybe he hadn’t been such a prize even back when he was young. To the rosy, wistful picture of a youthful Omar Yussef, he ought to have added that his eyes would be bleary from drink and his mouth would be tight with the bitterness of one who feels he has much for which to apologize—to those he offended while drunk, but to himself most of all. Yes, perhaps he truly didn’t need this in the morning. He would talk about retirement with his wife Maryam.

More students came into the room. Most were silent. They knew enough of Omar Yussef’s strictness not to speak in class unless he appeared to be in a very good mood, which rarely applied to the opening of the morning session at 7:30 a.m. But one girl was too animated to hold herself back. Khadija Zubeida entered quickly and excitedly. She was tall and thin with black hair cut in a bob. There was an early bloom of acne high on both of her pale cheeks. Before she sat, she leaned over the desks of two friends: “My dad called me before I came to school,” she told them. “He arrested a collaborator. The one who helped the Israelis kill the martyr in Irtas. He said they’re going to execute the traitor.” She spoke in a whisper, but in the quiet classroom it was audible to all, as was the snigger that punctuated it.

“Who was it?” one of her friends asked.

“The collaborator? He’s a damned Christian from Beit Jala. Saba, I think. He led the Jews right to the man in Irtas, who was a great fighter, and he delivered the final blow with a big knife that the Jews gave him.”

Omar Yussef put down his pen before the shaking of his hand could propel it across the table. He shoved the exercise book away from him and put his head in his hands to gather his thoughts. They had taken George, he was sure of it. He coughed to steady his voice. “Khadija,” he called to the girl, hoarsely. “Which Saba?”

“I think he’s called George, ustaz. George Saba. My dad says he keeps dirty statues of women in his house and he offered to let the arresting officer take his daughter instead.”

The girls clicked their tongues and shook their heads.

“The Christian confessed, too. He said, ‘I know why you came here. You came here because I sold myself to the Jews.’ My dad gave him a good thump after he confessed.”

Omar Yussef stood and leaned against his desk. “Come here,” he said, sharply. As the girl approached him, a little confused, he considered giving her the same blow her father claimed to have aimed at the collaborator. But he knew he must try harder than that: he was a schoolteacher, not a police thug. He wondered what the girl saw from the other side of the desk. He knew that his own eyes were tearing with rage and the slack fold beneath his chin trembled. He must have seemed pitiful, or deeply unnerving. “What do I teach you to do in this classroom?”

The girl looked dumbly at Omar Yussef.

“How do I teach you to look at history?” Omar Yussef waited. He stared closely at the girl. There was no reply, so he went on. “I teach you to look at the evidence and then to decide what you think about a particular sultan, or about the causes of a war.”

“Yes, that’s right,” the girl said, relieved.

“So how do you know that this man was a collaborator?”

“My dad told me.”

“Who’s your father?”

“Sergeant Mahmoud Zubeida, General Intelligence, Rapid Reaction Force.”

“Did he do the investigation, from start to finish?”

The girl looked perplexed.

“No, of course, he didn’t,” Omar Yussef said. “So you’d need to talk to all those who did investigate the case before you could come to the conclusion that this man was a collaborator. Wouldn’t you?”

“He confessed.”

“Did he confess to you? In person? You’d need to talk to him. To understand him. To talk to his friends. Most of all, you’d need to find his motive for collaborating. Did he do it for money? Maybe he already has a lot of money and has no need of more. So then why would he do it? Was there anyone else who might have done it to set him up? Maybe a business rival?”

The girl shifted from foot to foot and scratched at the spots on her cheek. Omar Yussef saw that Khadija was about to cry. He knew that he was shouting now and leaning very close to the girl across the desk, but he didn’t care. He was infuriated by the ignorance of an entire generation and saw it concentrated in this girl’s thin shoulders and blank face.

“How could I know all that?” Khadija stammered.

“Because it’s what you need to know before you condemn a human being to death.” Omar Yussef leaned as far forward as he could. “Death. Death. It’s not something light, something to giggle and boast about. This alleged collaborator is someone’s father. Imagine having your father taken away and knowing that he will be killed.” As he spoke, it occurred to Omar Yussef that the girl probably had frequent cause to imagine her father’s death at the hands of the Israelis in some stupid gunbattle. It was probably in Khadija’s nightmares each night, coruscating and terrifying. It made Omar Yussef feel, for a moment, sympathetic. He stood up straight. “Sit down, Khadija.”

Omar Yussef took out his comb and straightened the strands of hair that had fallen forward when he shouted at her. The class was silent. He returned his comb to his top pocket and sat. “When you are gone from the world, what will you leave behind?” he said. “Will you leave behind many children? So what? Is that a good thing in itself? No, it depends on what you will have taught them. Will you leave a great fortune? Then, what kind of person will inherit it? How will they spend it? Will people remember you with love? Or will they feel hate when they think of you? Start asking yourself these questions now, even though you are only eleven years old. If you do not ask these questions of yourself, someone else—maybe a bad person—will dictate the answers to you. They will show you their so-called evidence, and you will never see all the other choices available to you. If you do not take charge, someone else will gain control of your life.”

I might be talking about myself, Omar Yussef thought.

“This man, George Saba, was once my student. He was a very intelligent, good pupil. He was sensitive and funny. He was also moral. I don’t believe he would become mixed up in anything criminal or bad.”

Khadija Zubeida didn’t raise her head as she spoke sullenly. “What evidence do you have?”

Omar Yussef was pleased with the question and he nodded at the girl. “More than you, Khadija. Because you judge the case according to your feelings of hate for someone you’ve never met. I know George Saba and I love him.”

Well, that was a smart way to start the day, Omar Yussef thought. I love the Israeli collaborator; I love the worst traitor. Next time anyone’s looking for a dupe, stick me in jail and get my class to testify that I sympathized with a collaborator, which surely makes me a collaborator, too. Good job, Abu Ramiz. You need more sleep and an extra cup of coffee in the morning.

When classes ended for the morning, Wafa, the school secretary was waiting outside the room. She wore a thin, fixed smile and handed a small cup of coffee to Omar Yussef.

“God bless your hands,” Omar Yussef said. “I assume this fine treatment means that you are preparing me for bad news.” The cup rattled against the saucer. His hand shook more than usual. George, he thought, Allah help him.

“Drink your coffee, ustaz,” Wafa said, and the smile became more affectionate.

Omar Yussef stared at her, waiting.

“The director wants to see you as soon as possible in his office,” she said.

“Thank you for the coffee.” Omar Yussef drank. “It’s delicious.” He returned the empty cup to Wafa. “You see, I didn’t even curse when you mentioned our esteemed director.”

“For a change. We must thank Allah.”

Omar Yussef entered Christopher Steadman’s room and immediately the friendly warmth he had felt with Wafa changed to anger. At the side of the desk, next to the tall, fair figure of the UN director, was the government schools inspector who had forced the Frères School to terminate Omar Yussef’s contract a decade earlier. Omar Yussef knew immediately what this would be about. The bastard from the government had stopped Omar Yussef tampering with the minds of the elite at the Frères School. Now he figured he could cut off his piffling influence over even the bottom of the pile here in the refugee camp, where, after all, the corrupt scum who ran the government recruited their expendable foot soldiers. Omar Yussef was angry, too, because he understood that he was being summoned into the presence of the inspector to give Steadman more leverage in his push for his retirement. “Sit down, Abu Ramiz.” Steadman gestured to a chair in front of his desk. Omar Yussef noted that the American had picked up on the tradition of calling an acquaintance the “father of” his eldest son.

Only the day before, Steadman had asked Omar why Arabs called each other Abu or Umm? Omar Yussef explained that Palestinians each have a given name, “so I am Omar,” he said. “But we also are known as the father—Abu—of our first son. My first son is Ramiz, so people call me Abu Ramiz. The father of Ramiz. It is more respectful, more friendly.” Then he warned Steadman that if he made him retire, he wouldn’t have anyone to pester with questions about Arab society. Steadman proceeded as though he hadn’t noticed the aggression in what Omar Yussef said. “If I had a son, which I don’t, I always thought I’d call him Scott,” Steadman said. “So I’d be Abu Scott.” Then he asked Omar what Umm means. Omar decided to confuse him: “It means ‘Mother of.’ My wife is Umm Ramiz, just like I am Abu Ramiz. My son decided to name his first son after me, because he believes in following this tradition, so he is Abu Omar and his wife is Umm Omar, and their son Omar will one day name his son after his own father and be called Abu Ramiz, too. And you,” Omar said, “will always be just an American.”

Now, in Steadman’s office, Omar Yussef could see that the American was trying hard to fit in. All right, so you remembered, he thought. You called me the father of Ramiz, Abu Ramiz, but you won’t make me like you so easily.

The room smelled. That, too, was the result of Steadman’s attempt to conform to local traditions. Before Ramadan, Omar Yussef joked with him that Muslims refrained from washing during the holy month and were offended by those who did. At first, he found it hilarious that Steadman took him seriously. The director evidently planned not to bath for the entire month. Omar Yussef regretted the joke now and sniffed the cologne on the back of his own hand to overcome the reek of body odor. “Do you know Mr. Haitham Abdel Hadi from the Ministry of Education?” Steadman asked.

You know perfectly well that I know him. I’m sure he’s shown you his file on me, Omar Yussef thought. He remained silent.

“Well, I must tell you that Mr. Abdel Hadi has received some complaints about your teaching. This is why I’ve called you in here today.” Steadman stroked his thin, blond hair back from a sunburned forehead. He brought his hand down with the palm open, giving the floor to the government inspector.

The government inspector read from a series of letters he claimed parents had written to his department. The letters quoted Omar Yussef criticizing the president and the government, lambasting the Aqsa Martyrs Brigades as gangsters, condemning suicide bombings and talking disrespectfully about the sheikhs in some of the local mosques. “Last month,” the inspector said, “some of the students were hurt in a demonstration against Occupation soldiers at Rachel’s Tomb. The next day, teacher Omar Yussef told them that instead of throwing stones at soldiers, children should throw stones at their parents and their government for making a mess of their lives. This is a precise quote: for making a mess of their lives, throw stones at their parents and their government.”

“Is that what you said, Abu Ramiz?” Steadman asked.

Omar Yussef looked at the dark, sly eyes of the government inspector. He held his hand over his mouth, trying to make the gesture look casual. He hoped it would hide the angry twitching in his lip. He felt adrenaline filling him with rage. Steadman repeated his question. His innocent tone infuriated Omar Yussef.

“I don’t expect you to be absolutely politically correct, Abu Ramiz. You’re too old for that,” Steadman said. “But I cannot accept this kind of thing. We work in cooperation with the local administration and we’re not supposed to be breeding revolutionaries, or encouraging acts of violence.”

This stupid man really thought I wanted the children to attack their parents. “The children were already violent. They attacked the soldiers. I hope it’s not revolutionary to point out that this is still an act of violence, whatever their reasons for doing so. I was suggesting to the children that the guiltiest target is not always the most obvious one,” he said.

“That is outrageous,” the government inspector said. “To place parents and the government before the Occupation Forces as criminals against the Palestinian people.”

“It’s politically correct these days to blow yourself up in a crowd of civilians. It’s politically correct to praise those who detonate themselves and to laud them in the newspapers and in the mosques.” Omar Yussef banged the edge of his hand on the desk. “But you say that it’s outrageous for me to encourage intellectual inquiry?”

“You have a bad record, Abu Ramiz,” the government man said. “Your file is a lengthy one. I will have to institute official proceedings against you, if you do not agree to Mr. Steadman’s proposals.”

Omar Yussef looked at Steadman. The square American jaw was firm. The lips were tight. Steadman adjusted his small round spectacles. He squinted and watched Omar Yussef calmly with his little, blue eyes.

So this bastard already told Abdel Hadi he wants me out of here. Who knows if they didn’t cook this up between them? He decided he wouldn’t make it easy for them. He would never retire. They could put him in a jail cell with George Saba before he’d accede to Steadman’s weakness and pandering. “This would never have happened when the school was run by Mister Fergus or Miss Pilar. They would never threaten me. Yes, I consider this a threat, not just from the government but from you, too, Christopher. I end this conversation.” He went to the door.

“Abu Ramiz, you may not leave yet,” Steadman said. “We need to clear this up.”

“I am happy that you listened to my lecture about ‘Abu’ meaning ‘father of,’” Omar Yussef said. “Would you like me to refer to you as Abu Scott, as you suggested, after all?”

Steadman seemed taken aback by Omar Yussef’s change in direction, and he answered warily. “Yes. Like I told you, I always figured I’d call my son Scott, if I had one. So that makes me the father of Scott. Sure, you can call me Abu Scott.”

“It is a most appropriate name. In Arabic, Scott means shut up.” Omar Yussef stared at the confused American and the furious government inspector. “Excuse me, but I have a condolence call to pay in Irtas. The husband of one of my former pupils has been killed by political correctness.”

Chapter 4

The path through the valley was marked by a languid stream of mourners for the martyr. They sauntered along the track to the Abdel Rahman house, chatting idly. Omar Yussef cursed himself for wearing only a jacket that morning, as the wind rushed down the valley of Irtas and through his tweed. He decided to put on a coat every day until April, no matter how bright the weather looked from his bedroom window when he awoke. He moved as fast as he could, but was passed by almost everyone, though they seemed to be in no hurry. He was thankful at least that he wore a beige flat cap of soft cashmere to warm his bald head and to keep his strands of hair under control in the stiff breeze.