5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When Omar Yussef travels to New York for a UN conference, he is eager to see his youngest son, Ala. But the discovery of a decapitated corpse in his son's empty apartment lands him in the midst of a police enquiry riddled with contradictions. Desperate to clear Ala's name, Omar's investigation to uncover the murderer leads him towards a deadly international conspiracy...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

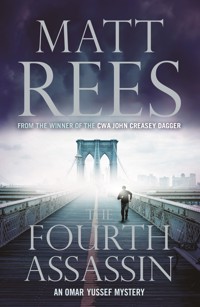

ALSO BY MATT REES

The Bethlehem Murders: An Omar Yussef Novel

The Saladin Murders: An Omar Yussef Novel

The Samaritan’s Secret: An Omar Yussef Novel

Copyright

First published in the United States in 2008 by Soho Press, Inc., 853 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Matt Rees, 2010

The moral right of Matt Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-84887-203-5

Contents

Cover

Also by Matt Rees

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

For my brother Dominic

and my sister Melissa

Chapter 1

As he left the R train and came up the narrow, gum-blackened steps from the Fourth Avenue subway in Brooklyn, Omar Yussef glanced around for armed robbers and smiled. He recalled the secretary of his school in Dehaisha Refugee Camp warning him that New Yorkers would gun you down for a dollar. The scattered pedestrians stooped, as if beneath some invisible burden, scuttling over the wide sidewalks of Bay Ridge Avenue. Their heads lowered to the cold wind, they dropped into the subway without looking at him. He thought of the response he had given his worried co-worker: “I’m a Palestinian. Brooklyn will be a vacation from the dangers of my life in Bethlehem.”

The sky was a blank, featureless gray above the three-story row houses. To Omar Yussef, the upper half of the landscape appeared to be missing, as though it had been concreted over. He checked his wristwatch and wondered if he had miscalculated when he set it to New York time. Its champagne-colored dial told him it was noon, but he couldn’t remember ever having seen the sun so absolutely obscured at its zenith, even during blinding desert sandstorms.

He came to the corner of Fifth Avenue. From his pocket he withdrew a slip of paper. With freezing fingers he lifted it close to his face and read the address scrawled across it. This, it seemed, was the right place. He sniffed and frowned at the tawdry shops along the block. He shambled past a jeweler’s which bore the name of a famous Ramallah clan in Arabic characters on its purple awning and a café named for Jerusalem, al-Quds, the holy. Across the street, a doctor whose family Omar Yussef knew in Bethlehem had his office and, beside it, a sign proclaimed the offices of the Arab Community Association.

Omar Yussef shuffled along the broken sidewalk, skirting piles of dirty snow shoveled against battered newspaper-vending boxes. He squinted against a freezing gust and pulled his thin, fawn windbreaker around the slack skin of his neck. Drops of water blown from the tainted snow spotted his spectacles. He wrinkled his nose and pursed his lips.

This was his son’s home, the section of Brooklyn where his countrymen lived. Little Palestine.

Except for the Arabic signs above the shopfronts, the avenue appeared archetypally American to Omar Yussef. Pristine cars, polished to a luminous finish he had only ever seen in Bethlehem on a government minister’s sedan, nuzzled the brown snow at the curb. The Stars and Stripes rattled against the lampposts in the wind. For some puzzling reason, the gray, leafless trees along the sidewalk were adorned with large red ribbons tied in bows.

A Muslim woman hurried out of a halal butcher. Her head wrapped in a cream mendil, she puffed out her dark cheeks against the cold and hunched her shoulders beneath a coat that appeared to have been made for the Arctic. She caught Omar Yussef’s eye and, looking demurely to the ground as she passed, muttered, “Peace be upon you.”

“Upon you, peace,” Omar Yussef replied. With these words, the first he had uttered in Arabic since his Royal Jordanian Airlines flight had touched down at JFK, he felt suddenly homesick and filled with regret that he had arrived too lightly clothed for the New York winter. At home, snow came every two or three years and swiftly melted. Despite his son’s warnings, he had felt sure that New York’s weather couldn’t be so much worse. With his combination of extreme orderliness and dandiness, he had brought only a small half-filled suitcase, intending to add a few tasteful purchases of fine clothing before he returned to Palestine. Anticipating that he would buy a new hat, he had even left behind his favorite tweed cap. As he watched the woman haul her purchases along the block, Omar Yussef felt the white hair he combed over his bald crown lift on the raw wind.

At a door beside a boutique selling the traditional embroidered robes of the Palestinian villages which, in Arabic, confided that it was the establishment of someone named Abdelrahim, Omar Yussef checked the address once more. Then he shoved through the cheap black door and mounted the grubby staircase toward his son’s apartment.

The corridor at the top of the flight of stairs was dark and silent. Omar Yussef paused to catch his breath and to let his eyes adjust to the dim light filtering up from the ground floor. A bus pulled away on the avenue, and a car briefly sounded its horn. Someone was cooking in one of the apartments. He inhaled a smoky undertone of eggplant beneath the thick, fatty odor of lamb and recognized the dish as ma’aluba. No one slow-cooked the meat and eggplant so that their flavors rose through the pot, infusing the rice,quite the way his wife Maryam did. Once again he felt the sense of isolation that had come over him with those first Arabic words spoken on the strange street, as though the tongue, which tasted and talked, were the natural seat of loneliness. He pulled himself up straight. He reminded himself that his son, whom he hadn’t seen for more than a year and whom he loved, was waiting for him in one of these rooms, and he recovered a little of the excitement he had felt as he left the subway. He smoothed his gray mustache, smiled briskly to be sure that the chill outside hadn’t frozen his features, and scuffed along the narrow, sticky strip of red linoleum toward the door of apartment number 2A.

It was open.

Omar Yussef halted. An inch of iron-gray light groped past the door into the corridor. He knew little about Brooklyn, but he knew that it was not a place where people left doors unlocked, let alone ajar. He stilled his breath and listened. Another car honked on the street. The apartment was quiet. He knocked twice and waited.

“Ala,” he called. “Ala, my son. It’s Dad.”

Above the number, a strip of paper was taped to the door. On it, in a florid Arabic script, were written the words: Castle of the Assassins. Omar Yussef’s lips twitched in a nervous smile. Nizar always had good penmanship, he thought. That’s a nice joke.

He noticed a button in the center of the door. When he pushed it, a dull bell sounded, but the pressure of his finger also swung the door back on silent hinges. He stepped into the living room of his son’s apartment.

Once more he called his son’s name and added those of his roommates. “Rashid, Nizar? Greetings. It’s Abu Ramiz.”

The room was shabby, furnished with a dilapidated sofa and three dining chairs, one of which was missing its plastic backrest. On the far wall hung a cheap, yellow prayer rug woven with the image of the kaba, the black stone at the heart of the Great Mosque in Mecca. Beside it, a page torn from a magazine had been taped to the wall. It bore a photo of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. On a low table by the door sat a model of the same shrine made of matchsticks, the size of a football, painted gaudy yellow and turquoise. The kind of art our boys make in Israeli jails, Omar Yussef thought.

He crossed the room, with a wariness born of unfamiliarity and anxiety, and smelled the heavy, vinegary homeliness of foule coming from the tiny kitchen. He looked inside, noticed a grimy pot on the stove and a few brown smears of the fava-bean mash at its bottom. He held his hand over the pot and felt some warmth. A magnet advertising a Muslim community newspaper clamped a sheet of paper to the door of the refrigerator. It was a photocopy of the prayer times at a mosque called the Masjid al-Alamut.

Omar Yussef raised his eyebrows. Alamut, he thought. The real castle of the Assassins. These boys didn’t forget my history lessons.

He knocked at a bedroom door and looked in. The shades were closed. He reached for a light switch. The bed was unmade. In the small room, a free-standing closet obscured most of the window. A calligraphic rendering of the opening lines of the Koran in gold on black hung above the bed. On the windowsill, there were two framed pictures of Rashid. The first showed him with his parents. The second had been taken when he was a high-school student, posing with his three closest friends and his history teacher, a grinning Omar Yussef. He shook his head. The photograph reminded him of how quickly he had aged. Maybe it was only that the smile seemed out of place in his current life, so full of misery and death had his hometown become since the days when he had taught the boys who now lived in this apartment.

He went to the next room. One curtain was open. The window cast a dim light, enough only for Omar Yussef to make out that someone was there, lying in the shadows on the bed furthest from the door.

“Ala, my son? Wake up.” He knocked lightly on the door-jamb. “Nizar?”

The form on the bed didn’t stir. In the sickly light from the window, Omar Yussef could see a pair of legs clothed in well-pressed black slacks and shiny black ankle boots. He approached, squinting into the shadows. He reached out to shake the sleeper’s arm, touched the sleeve of a silk shirt, and found it was wet. He recoiled and yanked back the second curtain.

Omar Yussef stumbled, dropping onto the other bed. His pulse was suddenly overpowering. He pressed his hand to his heart as though to keep it from beating right through his rib cage and fleeing the apartment.

The man on the bed was dead. Where his head should have been, the darkness of blood soaked the pillow. A light gauzy piece of fabric had been laid above the ragged flesh of the neck. Blood covered the man’s shirt and was splattered across the wall. The corpse’s hands were bloodied too. Omar Yussef’s cheek twitched. His eyes blinked and teared up.

Is this my son? he thought. His shoulders shook and he went down onto his knees, crawling toward the bed. His hands slopped through the blood on the floor by the nightstand. He whimpered and a burst of acid vomit burned out of his mouth. It can’t be him. He wiped his sniffling nose and his lips with his wrist, staring at the body. The dead man had been short and slight, with a slim waist and delicate hands. He has Ala’s build. Do I recognize this shirt? Is it Ala’s?

On the nightstand, he saw a letter in his own careful hand. It lay unfolded beside the alarm clock, on top of a book of poetry by Taha Muhammad Ali. He picked it up. My dear son, Your dear mother sends her love, and your niece Nadia encloses a short story she wrote about something mysterious that happened in Nablus. Here are my travel details: If Allah wills it, I shall arrive for the UN conference on the morning of February 11 and shall come immediately to see you in Brooklyn. As we have discussed so many times and with such anticipation, you will show me around Little Palestine. . . .

He crumpled the pages in a bloodied fist and laid his shaking hand on the corpse’s chest. His pulse palpitated so strongly in his palm that his hand seemed to rise and fall, as though the dead man’s ribs still lifted with breath. The pooled blood seeped into his trousers, chilling his knees. May the King of the Day of Judgment forgive me for all my transgressions, he thought, and find it displeasing that this should be my boy before me. As his joints stiffened in the cold gore, he knew that he lacked the faith that might will this body back to life. He was not a believer. His prayer only made him feel more desperate and isolated. He shuffled backward, away from the bed, and wept.

Chapter 2

In his shock, Omar Yussef sat with the terrified, expectant stillness of a hunted animal. Eventually he wondered how long he had been on the floor of the bedroom. He watched his wrist lift like a corpse floating up through water. There was blood on the face of his watch. He rubbed it away with his thumb. Beneath the brown smear that remained, the dial showed one o’clock.

He heard a footstep in the living room. He waited. Three more steps, soft yet decisive. He sensed someone was just beyond the open door of the bedroom.

Maybe it’s Ala, he thought. He’s alive. He opened his mouth to call the name of his son, but then he glanced at the body on the bed. Or the murderer has returned.

He shoved himself to his feet, feeling as though all his muscles were encased in plaster. He was unsure if he intended to confront the killer or find a place to hide. His knees shook. His brain seemed to lurch into the backs of his eyeballs. He braced himself against the door frame as he stepped into the living room.

The front door was swinging and Omar Yussef glimpsed the back of a man clad in a black padded coat, black pants and shoes, and a black woolen cap. The man had bumped the edge of the matchstick model as he passed, and it toppled to the floor. Omar Yussef made for the door, but by the time he reached it the man was down the stairs and gone.

His neck spasmed with adrenaline. It could’ve been a thief who happened to see an open door and decided to try his luck, he told himself. But he was sure he had seen the killer. He felt isolated and vulnerable. What if the murderer realized that he had no need to flee from the feeble old man trembling in the bedroom?

On the floor by the sofa, he noticed the telephone. I have to get the police, he thought. He picked up the receiver, then halted. What’s the number for the emergency services in this country? He recalled reading an article which had explained why the deadly date had been so evocative for Americans, and he dialed.

A woman’s voice answered. “Nine-one-one emergency.”

Omar Yussef cleared his throat and spoke in his precise English. “I wish to report a death.”

“What is the mode of death, sir?”

Omar Yussef strained to comprehend the woman on the other end of the line. The operator’s voice had the impenetrability of poor diction forced to cope with a pre-scripted, elevated grammar. “I mean to say, it’s a murder.”

“How do you know it’s a murder, sir?”

The phone shook in Omar Yussef’s hand. “He has no head.”

“You have a dead person there with no head, sir?”

Omar Yussef nodded at the phone.

“Sir? That is the situation?”

“That’s correct,” he stammered. “No head.”

“What’s your location, sir?”

Omar Yussef looked around for the slip of paper with his son’s address. He checked his pockets, but it was gone. “I don’t remember the address. It’s in Bay Ridge. On Fifth Avenue. Above a boutique.”

“The name of the boutique, sir?”

“Abdelrahim. But that’s in Arabic. In English, it just says Boutique.”

“What’s your name, sir?”

“Are you sending the police now?”

“Yes, sir. What’s your name?”

“Sirhan. Omar Yussef Sirhan. From Dehaisha Refugee Camp.”

“Where, sir?”

“Ah, Bethlehem, in Palestine. I’m not American.” As he added that final, unnecessary information, Omar Yussef felt he had spoken from some kind of shame. It sounded to him like an admission of complicity in the murder of the man in the next room and those other murders infamously committed by his people in this land, a confession that he was an outsider not bound by the decency and trust that Americans believed they shared.

“Do you know the identity of the victim, sir?”

“Not absolutely.” Omar Yussef sensed the pressure behind his eyes again. He dropped to the sofa and put his hand to his forehead.

“Sir?”

“It might be my son.”

“Remain where you are, sir. The police are on their way.”

“If Allah wills it, let them come. Meanwhile, I’ll stay here, with him.”

“Sir?”

Only after Omar Yussef had hung up did he realize he had spoken his last words to the operator in Arabic.

He picked up the matchstick model. The golden dome was caved in on one side, where it had landed on the floor. He tried to poke it back into shape, but his fingers smeared brown over the matches. He stared at his sticky hands, went to the kitchen, and ran the hot water, rubbing the blood off his palms. On the back of his hand, a liver spot dappled his olive skin. He felt aged and frail. His body was decaying—but still it lived. He gasped, thinking that his son might never grow old.

When he turned off the water, he heard footsteps on the stairs. He went into the living room, fearing that the man in the black coat had returned. But the steps were casual and loud. It must be the police, he thought. Looking down at his brown trousers, he wondered if the bloodstains at the knees were obvious. He became suddenly afraid that he might be blamed for the murder. His hands may have left blood on his face before he washed them, so he removed his glasses and rubbed at his brow with the cuff of his windbreaker.

He put his spectacles back on and saw Ala in the doorway.

“Dad, peace be upon you.” The boy smiled, opened his arms, and approached Omar Yussef. The immobility of his father’s face stopped him. “What’s that on your trousers, Dad?”

“My boy, you’re alive.” Omar Yussef stroked the light curls of Ala’s black hair and felt the thin bristles of his mustache. At five feet seven, Ala was only an inch taller than his father, but he seemed to tower over the nervous, hunched man before him.

“Thanks be to Allah.” Ala grasped his father’s elbows and kissed his cheeks. “But what do you mean? Are you making a joke? Some parts of Brooklyn are dangerous, but Bay Ridge isn’t such a bad neighborhood.”

“My son, there’s a body in your bedroom.”

Ala gripped Omar Yussef’s arms harder. “What? Dad, be serious. What’s happening?”

Omar Yussef gestured toward his son’s bedroom and lowered his head. The young man stepped into his room.

“May Allah have mercy upon him,” Ala mumbled. “It’s Nizar.”

“My son, I thought it might be you.” Omar Yussef shuddered as he came to the doorway.

“That shirt.” Ala’s voice, edged with tears, broke. “Those shoes, he was very proud of them. He called them his ‘Armani boots.’ They’re expensive. It’s Nizar.” He took Omar Yussef’s hand, still pink and warm from the scrubbing, squeezed it with tremulous fingers, then turned back to his dead friend with glassy eyes.

Omar Yussef let himself fall to the sofa and tried to find a way to sit that would hide the blood on his trousers. He covered his lap with a cushion. It was embroidered red on black with the geometric tribal pattern customary in Bethlehem. He ran his forefinger over the thick stitching and wondered if Maryam had made it for her son. He closed his eyes and tried to visualize his wife, but Nizar’s face came to him instead. My old pupil, he thought. My dear boy.

Ala came out of the bedroom. The tears and the trembling were gone. His face was stern. Omar Yussef thought he detected pity and hate in his son’s narrowed, hazel eyes.

“The son of a whore,” the boy said. “Rashid. He finally did it. He killed Nizar.”

“No, he was his best friend.”

Ala shoved the front door hard. While its slam still echoed, he shouted, “Things have changed since we were all together at the Frères School, Dad.”

“Even so, murder? What could’ve driven Rashid to something like that?”

“You don’t want to know.”

“I won’t believe it. You can’t be sure of a thing like that.”

Ala turned to the window, pulled back a corner of the net curtain, and looked down at the gray street. His jaw stiffened, and his voice was sharp when he spoke. “He made it as clear as he could.”

“What do you mean?”

The young man rubbed the thin curtain between his fingers. “The Veiled Man.”

“What?”

Ala’s eyes stayed on the window, furious. “That bit of material placed over the pillow, where Nizar’s head would’ve been. It’s a veil. Like the veil worn by a woman.”

“But a veiled man?”

“You know as well as I do, Dad. You taught us about it in history class.”

“The veil worn in the messianic stories by the traitorous man, the enemy of the Mahdi.”

“That’s it. When our messiah, the Mahdi, comes, the man who opposes him is supposed to wear a veil, and the Mahdi will battle him and kill him.”

A siren sounded nearby.

“What does that have to do with Rashid?” Omar Yussef asked.

Ala shook his head. “Rashid and Nizar—”

The siren drew closer.

“Little Palestine isn’t as I’ve led you to believe, Dad,” Ala said. “America is very harsh. No one cares about my computer degree from Bethlehem University. I couldn’t find a decent job. It’s been the same for Rashid and Nizar. We’re just another gang of Arabs to the Americans, terrorists or supporters of terrorism, anti-American bigots who deserve bigoted treatment in return.” He slapped his hands against his hips and let his shoulders drop. “I’m not a programmer. I work as a computer salesman in a shop run by another Palestinian guy. To make ends meet, I drive a cab a few nights a week. Rashid and Nizar drive for the same company. I share this apartment with them because I can’t afford a place of my own.”

“What does that have to do with this? How does that prove that Rashid killed Nizar?”

“I’ve been here with them, close to them. I know how difficult life was for them here in America, and I know what went on between them.”

“Which is what?”

Ala rubbed his hand across his eyes and let the curtain drop over the window. “The police are here,” he said.

Chapter 3

The crime-scene technicians called out details about the body, its position and condition, its distance from the objects surrounding it. Their vowels were nasal and their tongues slapped distorted consonants into their front teeth, so that it was hard for Omar Yussef to understand them. Slumped in the corner of the couch, he wondered how he might explain to them why the dead boy had fled Bethlehem for Brooklyn. His hometown seemed distant and would surely be alien to these detectives. He feared they might misinterpret whatever he said for the worse, as those confronted by foreign situations usually do.

At the other end of the couch, Ala no longer appeared to be listening to the police. He stared at the scratches on the floorboards with his jaw clamped angrily. What is it that he knows? Omar Yussef thought. How can he be so sure this killing was the work of his roommate? He fought a resentful urge to lash out at someone for causing this disturbance to his visit. Despite himself, he blurted out, “Ala, what’ve you become involved in?” He instantly wanted to apologize, but Ala’s eyes were bitter and forbidding.

Omar Yussef tugged at his spectacles and sighed. “Do you remember,” he asked, “how Nizar used to tease Father Michel at the Frères School? How he used to imitate his accented Arabic?”

Ala touched his fingertips to his brow, covering his face and refusing to engage his father. But when Omar Yussef mimicked the shrug and pout of the Catholic priest who had taught the boy French as a teenager, his son giggled and joined in. “The Father used to say, ‘My boy, if I wished to offend you, I would call you a heretical Protestant, but instead I will stick to the facts and say you are merely a stupid child, eh?’ Nizar impersonated him perfectly.”

“Nizar was always the funniest boy.” Omar Yussef’s gaze was distant, lost in enchanted memories.

“When Father Michel was sick one time, Nizar took him a pot of his mother’s mouloukhiyeh to warm him,” Ala said.

“Yes, his mockery was always loving.”

Their laughter subsided, both of them drifting through their reminiscences of the man whose body lay in the next room.

A short, dark-skinned woman with straight black hair spraying across her narrow shoulders hurried through the front door. She pushed a headband back from her forehead and adjusted her round glasses before she unbuttoned her long blue overcoat.

Behind her, the doorway filled with the heavy shoulders of a tall Arab man. His features seemed familiar to Omar Yussef. Bulky and jowly above a thick neck, his head tapered to a small crown, the hair shaved almost away. His lower lip drooped, and he breathed through his mouth. He wore a trim black goatee, and his eyes were dark, languid, and hard.

“They sent the token Arab cop to handle the dead Arab,” Ala said.

Omar Yussef looked at the boy, appalled by his disrespect and hostility. He’s had a terrible shock, he thought, but there’s something more that’s eating him. He’s covering it with a shield of aggression.

“Not just an Arab cop,” the big man said in a voice that was low and rasping. “I’m Palestinian, and I’m not here to handle the dead Arab, as you put it. We have specialists in the dead, Arab or not. I’m here to handle you.”

He’ll understand our language and recognize the nuances in our statements, Omar Yussef thought. I hope that’ll make him forgiving of my son’s anger.

“What’re we looking at?” the woman called to the nearest uniformed officer. Her voice was high-pitched and sharp.

“The victim is back in the bedroom there, Lieutenant,” the officer said. “Should we, you know, inform the FBI?”

“The Feds?” She stared at him.

“The victim’s Arab,” the big detective said. “That’s what he means.”

“Yeah, that’s it.” The patrolman nodded.

“You think he’s some kind of suicide terrorist?” The Arab detective fixed him with the mirthless sneer of an imam at an orgy. “Did he cut off his head and throw it at someone? Maybe he kept a stockpile of illegal hand-grenades in his cheeks and one of them went off by accident.”

The patrolman scraped his foot back and forth on the linoleum in the entrance to the kitchen. “Ah, Jesus, Lieutenant,” he muttered, appealing to the other detective.

She shook her head and beckoned to the Arab detective. “Come on. Let’s see what we’ve got back there.”

The big detective followed her into the bedroom. As he went, he let his eyes linger on Ala. They had a drowsy intensity that made him look like a wrestler gathering strength between bouts.

Through the open door, Omar Yussef heard the Arab carry on a low conversation with someone already in the room. The other detective’s sharp voice described the location and condition of the body. She came into the doorway and glanced at Omar Yussef, still talking into a small voice recorder.

As he listened to her catalogue of Nizar’s visible features, Omar Yussef wondered how the detective might have described him, had he been the subject of her investigation. Victim appears to be over the age of seventy, though identity documents show him to be fifty-eight. Hair: white, combed over liver-spotted bald scalp. Eyes: brown. White mustache. Gold-rimmed glasses, Gucci brand. Shoulders and chest show general lack of physical activity. Clothing expensive and good quality. Blue shirt, monogrammed OYS; fawn cardigan and windbreaker; brown pants, bloodstained. As he mused, Omar Yussef looked up. The lieutenant was still in the doorway. She held her recorder to her chin, but she had stopped speaking. He saw that she had noticed the blood on his knees.

The Arab detective moved past the woman and stood above Omar Yussef.

“Greetings, ustaz,” he said, in Arabic. His voice was lighter than it had been, as though he were greeting a friend.

“Double greetings.” Omar Yussef stood.

“The other officers tell me you’re visiting from Bethlehem. That’s my hometown.”

Omar Yussef smiled and looked at Ala. “Did you hear that, my boy?” His son twitched his cheek and sneered at his hands.

“I’m Hamza Abayat. I grew up just down the hill from the Nativity Church.”

“I know the Abayats,” Omar Yussef said. “You’re from the Ta’amra clan.”

Hamza grinned broadly. “Welcome, welcome to New York.”

“Unfortunately, this is quite an unwelcome welcome.” Omar Yussef choked out a bitter laugh. He was surprised at how warmly he felt toward the policeman, simply because they shared a hometown. I must be feeling even more lost in this city than I suspected, he thought.

The lieutenant came out of the doorway and looked at Omar Yussef. “The victim’s Palestinian?”

“That’s correct,” Omar Yussef said.

She addressed herself to the Arab detective. “Here’s what we found in the victim’s pockets.” She held up a transparent plastic evidence bag containing a blue passport. “Jordanian passport, identifies holder as Nizar Fayez Khaled Jado, born Bethlehem, West Bank, April 18, 1984. How does this guy have a Jordanian passport if he’s Palestinian?”

“Palestinians don’t have a state, so they don’t have passports of their own,” Hamza said. “Not the kind that’re worth anything, at least.”

The lieutenant waved the Jordanian passport. “You were born in Bethlehem, Hamza. Do you have this kind of passport?”

“I have an American passport, Lieutenant.”

“Right, right.” The woman smiled and brandished another clear bag. “Wallet containing New York State driver’s license, bank card, Social Security card, all in the name of the said Nizar Fayez Khaled Jado, resident at this address. A couple of ticket stubs from the Cyclone at Coney Island and some paintball thing out that way, too—a thrill-seeker, this guy. Then there’s this one other bag. What does this say, Hamza? It’s in Arabic, right?”

“What’s paintball?” Omar Yussef asked. “Killing for fun,” Hamza mumbled, reaching for the last plastic bag. Spread inside it was a sheet of pink writing paper covered in delicate script. Omar Yussef noticed Ala look up, as the detective read.