5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

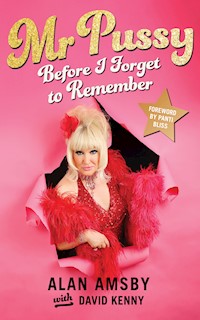

In 1969, a young Englishman named Alan Amsby arrived in Ireland with a frock and a wig. He was booked for one week, but was an overnight sensation, and made Dublin his home. Catholic Ireland had never before seen anything like the beautiful and outrageous Mr Pussy. For almost fifty years, Alan has delighted audiences and demolished boundaries. Here, he recalls his early days as a drag princess and model in Swinging London, partying the likes of Judy Garland, Noël Coward and David Bowie; being heckled by one of the Kray twins – and snogging Danny La Rue. He also remembers grey 1980s' Ireland, shocking the country with its first adult panto, and losing friends to the AIDS epidemic. Then there's his 1990s renaissance, 'doing time' with Paul O'Grady and Daniel Day Lewis, and opening Mr Pussy's world-famous Café De Luxe with Bono. Full of hilarious celebrity yarns, sequinned characters like the remarkable Stella Minge, and a lot of shameless name-dropping, Mr Pussy: Before I Forget to Remember is the story of a legendary, ground-breaking entertainer, full of pathos, charm and wit.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Mr Pussy

Mr Pussy

Before I Forget to Remember

Alan Amsby

with David Kenny

MR PUSSY

First published in 2016 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

Co. Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Alan Amsby and David Kenny, 2016

The Authors assert their moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-567-7

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-568-4

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-569-1

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my boyhood chum, Derek Banks, who died far too young. I wish we could have grown old together.

Contents

Foreword by Rory O’Neill (aka Panti Bliss)

Chapter One: The Kitten in the Pram

Chapter Two: The Cat-O’-Nine-Tails

Chapter Three: Bernard

Chapter Four: Cat on the Tiles in Soho

Chapter Five: West End Kitty

Chapter Six: Sequins and Sea Queens

Chapter Seven: Going Down on a Bomb Up North

Chapter Eight: Drag Comes to Dublin

Chapter Nine: Pussy is Born

Chapter Ten: The Grey, Gay 1980s

Chapter Eleven: Dublin in the Not-so-Rare Old Times

Chapter Twelve: Sour Puss Camps it Up

Chapter Thirteen: A Snog with Danny La Rue

Chapter Fourteen: Cat Burglar and Savage Do Time

Chapter Fifteen: Thank God it’s Friday … Opening a Café with Bono

Chapter Sixteen: It was a Bumpy Flight, Mum … But I Wouldn’t Change a Thing

Afterword by David Kenny

Acknowledgements

Foreword

by Rory O’Neill (aka Panti Bliss)

As a popular T-shirt says, ‘It takes balls to be a fairy’, but to be a fairy in full drag in 1970s’ Ireland (and with an English accent to boot!) took more than mere balls. It took nerves of steel, a mischievous sense of humour, a delight in the ridiculous, a steely determination, a quick wit, a brazen disrespect for authority, and a fabulous wardrobe. And luckily Alan Amsby had all that and more. He may have started out as a ‘mod’ in the 1960s, but ‘Ireland’s leading misleading lady’ was, and remains, a true punk.

The first time I became aware of Mr Pussy was some time in the 1970s when, as a boy who felt awkward and different in a small town in Co. Mayo, a glamorous and exotic gal with an equally exotic name shimmied onto our family’s black-and-white television screen. I have long since forgotten what the show was and by whom she was being interviewed, but I never forgot her. I couldn’t have told you then what it was about this glamorous creature that captured me, nor why I immediately felt an exciting frisson of recognition—as if a small part of me was being reflected back at me for maybe the first time, the same part of me that usually made me feel awkward and different, but here was being reflected back at me as something exciting and fun and (despite the monochrome screen) colourful. This gorgeous creature wasn’t ashamed of that part of her—she had thrown glitter on it and celebrated it. I was intrigued and impressed, and have remained intrigued and impressed by my ‘Aunty Pussy’ ever since.

One night many years later, having just returned to Dublin in the mid 1990s after a few years living abroad, I nervously approached her at the bar of the Kitchen nightclub in the basement of the Clarence Hotel. At the time, Pussy was the reigning doyenne of late-night Dublin, her Mr Pussy’s Café De Luxe the epicentre of Dublin’s new early Celtic Tiger nightlife scene. As always, she looked gorgeous: sequins spilling to the floor and blonde curls falling onto her shoulders, from which a fur coat slid languidly. I mumbled something about how much I admired her, and she looked me up and down—a skinny ‘baby drag’ wearing God-knows-what and a cheap wig—and like an imperious queen, she dismissed me gracefully. And I loved her even more for that!

But over time (I guess after she had decided I had paid my dues and wasn’t going anywhere!) Pussy decided to take me in. She became ‘Aunty Pussy’, always encouraging me and following my career with interest. Always ready with words of advice or a gentle admonishment. She was kind and generous to me, which she didn’t need to be, because whether she knew it or not she’d already given me and people like me a lot. By the simple but courageous act of being her glorious unapologetic self at a time when being herself (and himself) wasn’t easy or always welcome, she opened a door and made space for people like me in the country she adopted. And for that I will always be entirely grateful.

And it’s about time Alan finally wrote this book! He has enough stories for ten books, and I’ve been lucky enough to hear plenty of them over a drink. Or ten.

Chapter One

The Kitten in the Pram

‘Move your arse, Bill. I need to take a wee, and Alan needs to be changed.’

My father ran his fingers through his Brylcreemed hair in mock exasperation and looked at my mother, who was almost cross-eyed with gin and a full bladder.

‘Change him? Change him? We’ve only just bleedin’ got him.’

Mum threw her head back and gurgled like a freshly plunged sink. I laughed too, not understanding the joke, but absorbing their good humour like a terry nappy.

‘Oh, Bill. Get us a taxi, will you? I’ll never make it home.’

Dad protested.

‘Taxi? After what we’ve just spent in the battle cruiser [boozer]? No way, love. Shanks’s mare.’

‘Okay then, you tight old git, I’ve a better idea…’ Mum hoisted me out of the buggy and squeezed herself into the small, rickety frame. The wheels creaked, which said more about the state of the pram than her weight. My mum was a lovely looking woman with a petite, slim figure.

‘Go on, then. Get pushing.’ Dad laughed, gave the pram an almighty shove and set off at full tilt down Peckham High Street. The G-force (or whatever it’s called) sent my mum and me into the back of the pram. She hooted, and I wet myself. (Just a little. I was a very polite two-year-old.)

‘Ro-o-o-o-oll out the barrel …’ Dad sang the old music-hall song in the style of Hank Williams as he shoved us down the road.

‘Shut up about barrels, will you? I drank at least two of them. And mind the bumps. Oh, me waterworks!’

This is my earliest memory: Mum, Dad and me returning from a pub through south London, the sound of laughter ricocheting off the bombed-out buildings. We were a tight, happy little unit. Well, Mum was tight with gin, at any rate. I still recall how much they loved each other. If anyone looked at Mum sideways, backways or whatever, Dad would roll up his sleeves and there would be a dust-up.

I remember him flooring a fellow for giving him cheek on the way back from a night out. He was huge, my dad. A lorry driver who looked like John Wayne, without the mincing walk. I always thought John Wayne walked like a man with piles and the trots. Whenever I attempted to mimic him as a kid, I ended up walking like a bar-room tart. I was never cut out to be butch. Or a bitch. My parents saw to that. They raised me well: by example, being kind and loving. While Dad was tough and rough-edged, and Mum was a tartar when crossed, they were never cruel or nasty. As the cliché says, they hadn’t a bad bone in their bodies.

Mum and Dad met when she was sixteen and working in a tobacconist’s shop. He fell for her immediately. Well, she was a cracker. They went out on a couple of dates, but then she broke it off. ‘I’ll get you in the end,’ he vowed. A few months later, Mum was passing Elephant and Castle on the bus with her friend Eva, and got off to see if he was hanging around with his mates. He was. They took up where they had left off, got engaged and tied the knot. Then a short-arsed Austrian painter decided to pick a fight with Europe. Dad was never one to miss out on a good scrap, so he threw his lot in with old Montgomery and headed off to Africa to stick it to the Hun. He was gone for six years.

I don’t know how many German arses he kicked. He never spoke about the war in all the years I knew him. I can only suppose he saw some dreadful things. Eventually, Hitler did the decent thing and topped himself, and Dad came home. He quickly made up for lost time, and little Alan was born.

Mum was in her thirties when she had me, and she used to parade me around as she thought that having a baby made her look younger. But she did look young. She was a gorgeous woman, very glamorous, and so smart, acerbic and witty. I once asked her why I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. She said, ‘Oh, I did the sex thing once and didn’t like it.’ We had that kind of banter.

I don’t recall anything about my early, early, early years, except that before the 1960s everything was in black and white. The streets, the sky, the people. And there was a touch of grey and yellow too. I remember the fog. In 1952 a particularly nasty cloud of it shrouded London, causing the deaths of around 12,000 people. I remember the fog of my childhood as being straight out of a Sherlock Holmes film, and when it was a pea-souper a man would walk ahead of the bus carrying a lamp. He was there to prevent stupid gits from walking under London’s famous red double-deckers. He was an eerie sight in a halo of yellow light.

‘Oooooooooooh, there’s the bogeyman coming up from the river to snatch us,’ Dad would say. ‘But don’t worry, son; I’ll give him a smack in his chops if he comes near us.’ I would then snuggle in under his arm, all safe and happy to have this lovely, hard, decent lump of a man there to protect me.

When he wasn’t off driving his lorry or protecting me from ghoulies, Dad would take me to Clapham Common to play soccer and cricket, both of which I was very bad at. ‘On your head, son,’ he would call, lobbing the ball in my direction, intending me to head it.

‘What’s on my head, Dad?’ I would reply, feeling my hair for insects while the ball was making a perfect arc towards my face … THWACK.

‘You all right, our Alan?’ He would try not to laugh. And he always let me bowl at cricket for this reason. Dad never showed any sign of disappointment in my lack of male sporting prowess. He just used to smile a smile that said: he is who he is, and I love him.

Dad was a character and popular with his mates down the pub. If they were ever in trouble, physical or financial, he would help out with a closed fist or one full of money. We lived in Peckham, which everybody knows is the fictional home of Del Boy and Rodney Trotter. There was actually a Mandela House—Winnie Mandela—and it was a blind school, not a block of flats. I knew all the places John Sullivan references in Only Fools and Horses. He and I went to the same school, although I didn’t know him personally.

There were plenty of Del Boys and spivs knocking about at that time, still selling black-market luxury items. Anything you wanted, they could get off the back of a lorry—even guns. This was post-war London, and as kids we used to play on the bomb sites. For us it was a playground; for my parents it was a tragic landscape because of all the neighbours who were killed during the Blitz. Next door to my school there was a church. It was bombed out, and I used to climb through the rubble to get to classes. In the afternoons we used to play there—with real revolvers and army uniforms. Tin hats were prized as there was a lot of stone-throwing. To us, the sites were battlefields with trenches. Our guns were not loaded of course, and had been brought back from Europe by demobbed servicemen. Most of these were sold on to the wide boys, but some were kept as souvenirs, and we would borrow them to play with.

It wasn’t all soldiers and guns, though. We would also play knock-down ginger and all the traditional games. (I was ‘ginger’, but wasn’t easy to knock down.) We used to tie a string from one doorknob to another and run away. When the occupants tried to open the door, their neighbour’s knocker would rattle and they would try to answer their door. A tug-of-war would then ensue between the two houses, one door half-opening, the other banging shut. It was hilarious to watch. Try it sometime.

Only three million British homes had a TV by 1954. We were one of the few families in Peckham to have one. Not that I spent all day glued to it like today’s kids. We were outdoor children. The streets were safe back then (if you avoided the collapsing bomb ruins). Parents didn’t worry themselves sick like they do now about marauding gangs of paedophiles or traffic. In 1950 there were two million cars in Britain. The odds of getting knocked down were a lot less than they are today. Mum was so confident of my safety that, when I was little, she would send me around to the landlady to pay the rent. The woman used to give me an old penny with Queen Vic on it to buy sweets. The rent was a pound a week. It doesn’t sound like much, but in the 1940s a pound could buy you twelve pints of beer and ninety-six first-class stamps. I wasn’t around in the 1940s and had to look that up. In the 1950s it would get you twenty-six pints of milk. I can’t remember anyone ever actually buying twenty-six pints of milk all at once. It’s called ‘context’, dear.

I know all old geezers say this, but it really was a more law-abiding time. There were police boxes everywhere, like the one in Dr Who. You could see the reassuring blue light through the fog. Or if you were walking home late you always knew there would be a night watchman around the next corner, sitting in his hut beside a coke fire, protecting his roadworks and watching out for trouble.

Old ladies didn’t get mugged, and telephone boxes were fully glazed with intact directories and a paybox full of coins. We would never have dared to vandalise anything. We feared people in authority such as policemen and teachers. Even park keepers. We all knew that we would get a smack around the ear for misbehaving, and then another when we were brought home in disgrace.

That said, my parents never hit me when I misbehaved. Mum, who was the disciplinarian, had a ‘special look’ that she deployed when she wanted to terrify me—along with the other kids in the house we lived in. There were three families living there with two children upstairs, me in the middle, and a young fellow called Reggie downstairs. We were a little gang, scraping our knees, scrapping among ourselves and sharing sweets. We were popular with the grown-ups as we were good kids. We used to mess about, but were never too annoying. Neighbours used to look out for each others’ children then. They even bathed us. One thing we loved doing was climbing up on the old air-raid shelter in our yard while ‘Uncle’ Joe from upstairs would run a hose out of his window and shower us on sunny days.

‘Enjoying the hose-down, kids?’

‘Yessss,’ we’d shout back.

‘That’s not a hose I’m using …’

He had a filthy sense of humour did Uncle Joe.

Aside from outdoor showers, we kids all shared the same bath. Not at the same time, it has to be said. It was a galvanised metal tub that was kept in the yard and brought in at bathtime. We bathed on different days to the adults: grown-ups were always first. I can still see the fire blazing away in the grate and the front room full of steam, and hear the sound of my mum yodelling away as I did my ablutions, while Colin from upstairs awaited his turn. By the time I’d finished splashing suds all over the lino there was no water left for him.

After I’d been towel-dried before the fire, we’d have our tea, which was nearly always stew. Mum loved her stew, just like her mum before her. I still have the plates she used. They’re hanging on my wall here in Dublin. They’re late Georgian and probably worth a few bob, but I’d never sell them. Meat was scarce back then due to rationing, so everything went into the pot: dumplings, small pieces of lamb’s neck, carrots, toenails…. Okay, that last bit’s made up, although there was the occasional varnished fingernail. Mum used to say that her stew improved with age. Maybe it did, or maybe it was just wishful thinking. (I think I once spotted one of Sir Walter Raleigh’s original spuds at the bottom of the pot.)

‘It improves with age, just like you, Mum,’ I would coo angelically, hoping to score some points.

‘Are you saying your mother looks like a shrivelled up old lamb’s neck?’ Dad would lean across the table and pretend-glare at me.

‘No, no … I meant that she …’ I would stammer.

‘Ah, leave him alone, Bill. You’ve a head like a dried-up old dumpling yourself.’

We’d all laugh, and I’d spatter gravy down my napkin. God, I loved my gravy. The thought of it still makes me hanker for London’s pie and mash shops, where you could devour minced beef pies, spuds and parsley sauce (which we called ‘liquor’), with salt and pepper and vinegar. I also miss jellied eels. If you think that sounds like the most disgusting meal imaginable, then remember that the Irish invented coddle—a foul concoction of milk and boiled bangers and other assorted muck. Someone should open a pie and mash or a jellied eels shop in Dublin. They would make a fortune out of English stag parties: it’s great soakage grub.

As I’ve said, this was the age of rationing. The queues for basic food items began in 1940 (earlier in Germany, would you believe?) and British mums used to have to make ends meet as best they could. Less than a third of the food available in the UK at the start of the war was produced at home. Enemy ships targeted merchant vessels, preventing supplies from reaching us. The swine.

The first foods to be rationed were sugar, bacon, tea, meat and butter. Soap was rationed to one bar a month, and up until 1941 you could have only one egg a week. People used dried egg powder instead (to cook with, not to wash with, obviously). One packet of that horrible stuff was equal to a dozen eggs. This was fine if you liked them scrambled, but they were impossible to boil or fry.

Paper, petrol, washing powder and loads of things we take for granted these days were rationed. Spuds weren’t though. You could have any number of potatoes. You just couldn’t have chips, as oil was hard to get. Then there was Spam, which everyone has heard about, and the snoek, a fish from South Africa, which nobody has seen or heard of since. One person’s weekly allowance of the basics would be:

1 fresh egg

4oz margarine

4oz bacon

2oz butter

2oz tea

1oz cheese

8oz sugar

Meat was rationed by price, so cheaper cuts were popular. Points could be saved up to buy cereals, tinned foods, biscuits, jam and dried fruit.

There was no Lidl or Tesco; you went to different shops for different items. Greengrocers did fruit and veg; ordinary grocers did jam and tea and cheese; butchers did meat; fishmongers fish, etc. There was no wandering around with a basket or trolley; you were served by the shopkeeper from behind his/her counter. It was always a good idea to ‘keep in’ with the local grocer, who might hold extras for favoured customers.

Many people grew vegetables at home, and kept chickens, ducks and rabbits to eat. The rabbits loved their carrots, and so did the kids. There was a poster character called ‘Doctor Carrot’ which was used to encourage children to eat more of them. Here’s a fact you may not know: carrots don’t actually help you to see in the dark. That was a myth dreamed up by the Ministry of Propaganda to explain why the RAF was having such great success shooting down German planes at night. The truth was that the air force had introduced top secret on-board radar, which was giving the Bosch fliers hell. Whether Hitler believed this rubbish is unknown, but the mothers of England did, and carrots became a staple in most meals. They were sold as ‘treats’, and it wasn’t unusual to see children eating carrots on sticks instead of ice cream or lollies. We were an ingenious bunch back then. So ingenious that women used to paint gravy browning on their bare legs as a replacement for silk stockings.

Although I wasn’t born at the time to hear her, Marguerite Patten’s cooking tips on the Home Service drew six million listeners daily. Housewives were taught how to be creative, using ‘mock’ recipes which included ‘cream’ (margarine, milk and cornflour) and ‘goose’ (lentils and breadcrumbs).

You’d think that with all this rationing the health of the poor would have been a problem, but it actually improved as people were encouraged to eat more protein, pulses and fruit and veg. Babies, expectant mums and the sick got extra nutrients like milk, orange juice and cod liver oil (yuck).

Despite the hardship and the queues, nobody complained about rationing. It continued right up until 1954 as a large number of our dads were still in the armed forces—and, of course, the economy was buggered.

Anyway, this young kitten had to be different to all the other sturdy post-war kids. I got very ill when I was six and nearly died. Mum had done everything she could to keep my health up to scratch, but sometimes kids are just susceptible to illness, despite the best efforts of their parents. One of those best efforts was my mum’s advice always to wear a scarf and a hat to stop my hair getting wet. ‘You’ll catch your death,’ she’d say. Mums are great at giving mad advice like that. When did a child last get its arm broken as a result of upsetting a swan? When did someone last suffocate on account of swallowing chewing gum? And that is before you consider how difficult it would actually be to have someone’s eye out with a ladder, etc. Becoming an adult largely consists of coming to terms with the fact that most of what your parents have told you is utter crap. I don’t know if anyone has ever actually died after getting their hair wet, unless they stuck their damp head up against an electricity pylon. Or fell overboard. You’d definitely get your hair wet and die if you fell overboard. Well, I did get my hair wet, and I did nearly die, so she was almost right. I didn’t just come down with pneumonia; I was struck by DOUBLE pneumonia … and whooping cough … and jaundice … and all at the same time. It was horrible, fighting for air and burning up with a fever. I remember Mum and Dad standing beside the bed and me looking up and saying, ‘I’m Jesus. Mum, you’re Mary, and Dad, you’re Joseph.’ I was delirious. Dad went into the toilet and cried so hard that the neighbours came to see what the matter was.

My parents weren’t religious, and didn’t send for a priest like folk do in Ireland. I don’t know where I got the Jesus, Mary and Joseph stuff from either. Mum was hardly a virgin (as she had given birth to me), and I’m no Jesus—although I’ve been crucified with a hangover on more than one occasion. Dad came closest to sanctity as, like Jesus’s stepdad, he was very good with wood. (He built me a shed around the back of the house once, and also made me the most gorgeous US cavalry fort. Wasn’t Jesus crucified on Mount Cavalry? Or am I just bad at spelling?)

Anyway, the good news is that I pulled through (obviously), and lived to tell the tale here. The other good news was that all my aunts and uncles came to visit me and brought presents. I swear that the eighty gallons of Lucozade I drank over that period saved me. I even held on to my cough for longer than I should have to squeeze all I could out of my sickness. Eventually, Dad kicked my arse out of bed and shunted me off to school, just in time for the Christmas break.

That was the first Christmas I recall clearly. I woke up at about 6 a.m., and there was a pillowcase at the end of my bed, stuffed with gifts. Well, maybe not stuffed, but to a six-year-old it was Santa’s grotto. Before sweet rationing ended in 1953, the most treasured thing in your Christmas stocking—or pillow case—was a small two-ounce bar of chocolate. I got one of those and ate half, putting the rest under my blanket for safe keeping. Later, when I went down for breakfast, Dad nearly threw up: ‘For Christ’s sake, love, I thought we’d potty trained the child.’ The chocolate was stuck to the seat of my pyjama bottoms. He nearly fainted when I picked a lump off and stuck it in my mouth.

The rest of my gifts were unmemorable, except for one that looked like an odd-shaped bicycle pump. Great, there’s a bike waiting for me downstairs, I thought, ripping off the wrapping. It was a plastic trumpet. Despite what you may think, I was delighted, and woke the house up playing what I reckoned was Colonel Bogey, but in reality sounded like a bogie being blown.

‘Shut up, you little bastard.’

Uncle Joe upstairs was in that purgatorial stage between drunkenness and hangover.

‘Sorry, Uncle Joe.’

I blew a raspberry through the trumpet.

Later, we went around to Gran’s for Christmas lunch, and I was told I could bring my favourite present. I took the trumpet and tooted along with my extended family as they belted out ‘My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)’ on her rickety piano. My mum’s family were all musical and theatrical. Her aunt, Florrie Felden, who owned a pub in Vauxhall, had been a former music-hall artist. That’s where I get it from. Blame her.

Everyone would stand around the piano, drinking beer and doing their ‘turn’. All the wartime camaraderie was still there among the grown-ups. They were proud of their country and its part in Hitler’s downfall. They knew everybody on their street, and felt that they ‘belonged’.

After the singing, the oldies would play cards. That was a serious business, and the children would all be sent out to the parlour to play. Or fight. Or both. Despite all the rationing and hardship, Londoners liked to party. Uncle Joe used to have parties all the time. He had a wig and would dress up as a woman to entertain the guests.

‘Hey Joe, as a woman you look pretty …’

‘Oh, yes?’

‘… pretty fucking horrendous.’

Everybody loved a good drag act back then, and they still do. I used to watch him getting ready. Joe was gay, but nobody knew it. Not even his wife or kids. I think he was probably the one who initially set me on the road to drag superstardom. He played a fairly big role in my upbringing after Dad left us. The last memory I have of my father is of him waving to me.

‘You all right, son?’

‘I’m fine, Dad,’ I shouted back. He was a good nine yards away. The man next to him groaned a ‘shut yer gob’ in my direction. Dad, in turn, growled back at him. It wasn’t his usual growl though. It sounded like it was struggling to climb out of his mouth.

The sister on duty patted me on the head and gently led me back out into the corridor. The smell of disinfectant still clings to my memory’s hooter. Years later, whenever I arrived in a freshly cleaned and disinfected dressing room (which was rare), I would think of my dad in that hospital bed and ten-year-old me waving at him across the ward floor, my voice echoing among the bedpans and kidney dishes. They didn’t allow kids on the wards back then, and he was right at the end, in more ways than one. He had been taken in with a burst appendix. Mum had sent me to stay with my cousins while he convalesced.

The convalescence didn’t last long. ‘Peritonitis,’ I heard my auntie whisper to one of her friends when I returned to her house. ‘Blood poisoning.’

Two days later, I was brought home. I sat in my chair and saw Dad’s ring on Mum’s finger. I knew that something was wrong.

‘What’s up, Mum? Why did Dad give you his ring?’

She kneeled down beside my chair. ‘I have something to tell you, son …’

Seven little words have never hurt so much.

Dad, my hero and playmate, was dead. Mum and I were on our own. I cried for days. There were times when I felt like I was drowning. Eventually, the torrent became a trickle. Mum knew that life had to go on. I think I knew it too. What else was there for me to do? The kitten had to start growing up.

Years later, when I was visiting Peckham, I popped upstairs to see Joe, who was an elderly man by then.

‘Did your mum ever tell you that we have a ghost in the house?’

She hadn’t.

‘It’s your dad, Alan. I’ve seen him.’ I felt a chill.

‘He’s still here. He never left you.’

Chapter Two

The Cat-O’-Nine-Tails

‘Roger Green, stand up.’

The assembly hall stank of stale breath, wax polish, rotten apples, wet dog and sweat. The latter aroma emanated from just one pupil—Roger Green. He was sweating like a piggy in a sausage factory. You could literally smell his fear. The rest of us were giddy with nervous excitement at the prospect of what was about to happen to him.

Roger was a small boy for his age, with large jug ears and a dray horse’s fringe. He also had a stammer and rolled his R’s, which was very unfortunate. To look the way he did and have a speech impediment was bad enough in a school where you could be wedgied just for wearing polished shoes (this was considered ‘lah-di-dah’ and pretentious). To have TWO speech impediments was considered plain inflammatory. Roger spoke like a cross between an anti-aircraft gun and Jonathan Ross, and might as well have had a sign pinned to his arse saying ‘Kick Here’. Whenever the big lads saw him crossing the yard they would shout, ‘Wedgie Wodjah!’ Thinking back, I can’t understand why his folks didn’t change his name from Roger to, say, ‘John’, when he started to speak. Cruel bastards.

Roger had been caught stealing conkers from a display cabinet in the school. Most schools had trophy cabinets; we had conker cabinets. Actually, it was probably a science display or something. Who cares? Theft of any kind—even one as pathetic as this—was punishable by caning or expulsion. Even our school, which was as strict as they came, couldn’t throw a boy out for stealing conkers. It would have been a hard one to explain. And so Roger was brought before the whole school to be caned. The poor chap shuffled down the length of the hall towards the raised stage and climbed the stairs with his head bowed as if he were about to be crucified. I wasn’t brought up to be religious, but one wag, who had obviously been to Sunday school, picked up on the Jesus, Barabbas and Pontius Pilate theme. As Roger reached the top of the stairs, the smart-arse shouted: ‘Welease Wodjah!’ It made the entire assembly corpse for at least two minutes. This actually happened, and I have to point out that it was a couple of decades before Monty Python had even dreamed ofThe Life of Brian.

The punishment was horrible. I can still see the headmistress, Miss McGregor, standing in the assembly hall, waiting to give the order to begin the flogging—like Captain Bligh from Mutiny on the Bounty. She treated Roger like he was a sailor who had stolen water from the ship’s barrel. To her right stood our sullen form master, Mr Tizer. He looked miserable, as usual. We had nicknamed him ‘Tizer’ because of his sparkling personality. If it were raining champagne, sad old Tizer would have left the house with an umbrella. But he was far from the worst of them. I liked him, and he seemed to have a soft spot for me.

Miss McGregor, on the other hand, was only ever interested in finding pupils’ soft spots—and applying a cane to them. She was a complete psychopath; a sour old sow who suffered from chronic piles. We knew this because she kept an inflatable ring covered with a headscarf under her desk, and would slip it onto her chair whenever she had to sit down (she suffered from varicose veins too). She was a real horror when the veins and piles were flaring up. She must have been having a bad day on this occasion. ‘Begin the caning,’ she said through gritted teeth. Roger screamed and screamed as the bamboo thwacked off his backside. He was eight. Then, when we thought he’d had enough, she said, ‘More.’ I lost count of the blows he received. As I said, my mum never hit me; she just gave me her look. Her dad did the same to her. You don’t need to beat kids up to punish them.

Once McGregor had deemed his punishment sufficient, she dismissed the assembly, and Roger shuffled painfully off to class, snot and tears streaking the front of his jumper. Mr Tizer looked as though he was about to cry too. I still get angry when I think of the state Roger was in over bloody conkers.

He got his own back eventually, though. Months later, Old Sow McGregor sat down on her pile cushion at the start of assembly and leaped four feet in the air, howling like a banshee with nettles in her knickers. Roger had smuggled in five large conkers and gently deposited them in the centre hole of her inflatable ring. I say ‘gently’ because, unlike the conkers he had stolen, these were still in their green husk with their spikes on. McGregor had to take a week off sick, and never found out who had spiked her bottom.

Actually, that last bit isn’t true. I just made it up. Life went on as normal. There was no payback, although we pupils shared scenarios like the above to make us feel better. Roger’s punishment, and McGregor’s lack of answerability, was an early lesson in the unfairness of life.

With such happy memories, would you be surprised to learn that I hated school? I disliked everything about it. The lessons in maths and Latin that I would never use, the defeated air of the teachers trying to fill young heads with facts, the frequent violence in the yard and the class … And the school dinners. My God they were disgusting. All I can recall is green slop, probably cabbage, and pink meat, probably bacon. Form master Tizer used to sit at the top of the table near the food counter as we queued for our meal. Some of the poorer kids would sit near him because occasionally the dinner ladies would call ‘seconds’, and those at the top of the table always ate twice (if they had the stomach for it). They must have been hard up, those kids, to eat that muck. The only thing that was almost palatable was the spotted dick, and naturally I gravitated towards that.

When I wasn’t in school I was very much a free agent. Mum was always working. After Dad died, she held down three jobs to support us. She would rise at 5 a.m. to go office cleaning, come home to get me ready for school, then head to the BHS to work as a cook, and at night she worked as a barmaid. Incredibly, she never looked worn out or frazzled. She had good genes, my mum.

She didn’t remarry after Dad died, but she had boyfriends. I especially liked the ones who gave me ten bob when they came around—to bugger off.

At night, the neighbours took turns to look after me. Mum had a wonderful support network, and I had a wonderful childhood. I wanted for nothing. At weekends, when she wasn’t working, Mum brought me out shopping, and I was always well dressed. I gravitated towards the more flamboyant clothes, but Mum wouldn’t let me dress like a spiv in pinstripes.

A friend of hers brought me to get my hair done once as a treat. They tonged it (as opposed to tongued it), and I felt like a billion dollars. The next day I went to school with more waves than the English Channel, and loved all the attention I got. Unfortunately, it started to snow at lunchtime, and we had a snowball fight. My hairdo was ruined, and I was distraught. Mum spent half an hour re-rolling it with her fingers and pinning it up when I got home. My hair was naturally straight. Probably the only thing about me that was straight. I was the least boyish boy in Peckham, and I loathed sport. I’ve always been naturally thin and fit, and have never needed to run around fields chasing balls to keep my figure trim. It’s all a load of macho nonsense. On Wednesdays, the other boys would pile into a bus to go and play a match somewhere. I’d slip away and head to the pie and mash shop. Nobody gave me any grief for that. Mind you, nobody wanted me on their team. You might think that I was picked on as a result of my lack of machismo, but I wasn’t. I was a popular kid, and used to make my mates—and the school bullies—laugh.

Even the milkman knew ‘Young Master Amsby’, and enjoyed giving me a lift on his carthorse in the mornings on the way to school. I used to clown about for him doing Roy Rogers impressions. I suppose I was what you might call a ‘character’. I had a lot of friends, and my two best mates were Clifford Inso and Roy Farrington. Roy was one of the toughest boys in school, but he used to look out for me. I think he may have had a bit of a crush on me, but nothing ever happened. We bunked off together every Friday afternoon and would go to each other’s houses to listen to Elvis, Lonnie Donegan and Cliff Richard records, or go for pie and mash. I don’t know how I kept my gorgeous figure eating all those pies.

I went away to scout camp when I was thirteen, and I think Roy was a bit lonely at the thought of me leaving. He came up to the back of the lorry where I was sitting and said, ‘You have a good time.’ He reached out to shake my hand, and I could feel something small and disc-shaped between my fingers. He had slipped me a half-crown—a small fortune. It was a very sweet gesture, both paternal and fraternal. I still don’t know where he got the half-crown. Probably half-inched it.