13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

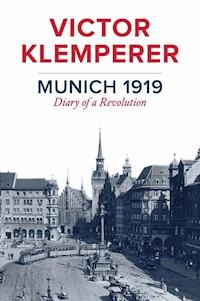

Munich 1919 is a vivid portrayal of the chaos that followed World War I and the collapse of the Munich Council Republic by one of the most perceptive chroniclers of German history. Victor Klemperer provides a moving and thrilling account of what turned out to be a decisive turning point in the fate of a nation, for the revolution of 1918-9 not only produced the first German democracy, it also heralded the horrors to come. With the directness of an educated and independent young man, Klemperer turned his hand to political journalism, writing astute, clever and linguistically brilliant reports in the beleaguered Munich of 1919. He sketched intimate portraits of the people of the hour, including Erich Mühsam, Max Levien and Kurt Eisner, and took the measure of the events around him with a keen eye. These observations are made ever more poignant by the inclusion of passages from his later memoirs. In the midst of increasing persecution under the Nazis he reflected on the fateful year 1919, the growing threat of antisemitism, and the acquaintances he made in the period, some of whom would later abandon him, while others remained loyal. Klemperer's account once again reveals him to be a fearless and deeply humane recorder of German history. Munich 1919 will be essential reading for all those interested in 20th century history, constituting a unique witness to events of the period.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword: Christopher Clark

Notes on the text

Munich 1919 Diary of a Revolution

Politics and the Bohemian World: February 1919

Revolution

Two Munich Ceremonies: February 1919

Revolution: Munich After Eisner’s Assassination: February 22, 1919

Revolution: The Events at the University of Munich: April 8, 1919

Revolution: The Third Revolution in Bavaria: April 9, 1919

Revolutionary Diary

April 17, 1919

April 18, 1919

April 19, 1919

April 20, 1919

April 21, 1919

April 22, 1919

April 30, 1919

May 2, 1919

May 4, 1919

May 10, 1919

Revolution: Munich Tragicomedy: January 17, 1920

Appendix

The German Revolution of 1918–19: A historical essay Wolfram Wette

Chronology

About this edition

Picture credits

Index

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

viii

ix

x

xi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

185

186

187

188

189

190

The first page of the manuscript of Klemperer’s 1942 memoirs on the Revolution of 1918–19.

VICTOR KLEMPERERMunich 1919

Diary of a Revolution

With a foreword by Christopher Clark and a historical essay by Wolfram Wette

Translated by Jessica Spengler

polity

First published in German as Man möchte immer weinen und lachen in einem. Revolutionstagebuch 1919 © Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 2015

This English edition © Polity Press, 2017

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press350 Main StreetMalden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1062-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Klemperer, Victor, 1881-1960, author.Title: Munich 1919 : diary of a revolution / Victor Klemperer.Other titles: Man mochte immer weinen und lachen in einem. EnglishDescription: English edition. | Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA : Polity, 2017. | First published in German as Man mochte immer weinen und lachen in einem: Revolutionstagebuch 1919. | Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2016048318 (print) | LCCN 2016055458 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509510580 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509510610 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781509510627 (Epub)Subjects: LCSH: Klemperer, Victor, 1881-1960--Diaries. | Bavaria (Germany)--History--Revolution, 1918-1919--Sources. | Munich (Germany)--History--20th century--Sources. | Young men--Germany--Munich--Diaries. | Philologists--Germany--Munich--Diaries. | Jews--Germany--Munich--Diaries.Classification: LCC PC2064.K5 A3 2017 (print) | LCC PC2064.K5 (ebook) | DDC 943.085092 [B] --dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016048318

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Foreword

Christopher Clark

The wave of political tumult and revolution that crashed over Germany at the end of World War I was a key episode in twentieth-century history. A society already scarred by war and defeat found itself once again shaken to its very foundations. The emergence of a Soviet-style communist Left on the one hand and heavily armed, counter-revolutionary right-wing radical groups on the other led to drastic political polarization. The rhetorical escalation soon degenerated into violence. Freikorps troops clashed fiercely with Spartacists.

Nowhere was the expansion of the conventional political spectrum more dramatic than in Munich. On November 7, 1918, the King of Bavaria became the first German monarch to be toppled. The army defected to the revolutionaries and the king went into exile. After the Bavarian prime minister Kurt Eisner (Independent Social Democratic Party) was assassinated on February 21, 1919, the power struggle between left-wing and moderate socialists came to a head. The government of the new prime minister, Johannes Hoffmann (Social Democratic Party), was overthrown on April 7 and replaced with a Bavarian council republic led initially by pacifist and anarchist intellectuals. But barely a week later, the communists under Eugen Leviné seized power. Hoffmann’s cabinet, which had gone into exile, now asked the government in Berlin for help. In mid-April, Reichswehr troops and Freikorps units advanced on the Bavarian revolutionaries. The council republic was then brutally crushed, and an estimated 2,000 of its supporters – both actual and merely alleged – were murdered, summarily shot or sentenced to imprisonment.

Victor Klemperer guides us through the turmoil of these eventful Munich days with empathy, sensitivity, and a perceptive eye. This volume brings together contemporary accounts written for the Leipziger Neueste Nachrichten newspaper, only a fraction of which were published at the time, as well as related passages from a later memoir that Klemperer was forced to abandon in 1942. Thanks to the diaries he kept during the Third Reich, Victor Klemperer is one of the most frequently read eyewitnesses of the twentieth century. The keen judgment, eye for striking details, and literary talent he displays in that epic chronicle are also evident in the writings of the young Romance philologist in Munich who was concerned about his academic future.

This is Klemperer describing the entrance of the troops that crushed the council republic in the Bavarian capital in early May 1919:

… all through the day and late into the afternoon, as I write these lines, a thunderous battle has raged. An entire squadron of planes is crisscrossing Munich, directing fire, drawing fire itself, dropping flares; bombs and grenades blast constantly, sometimes farther away, sometimes nearer, shaking the houses, and a torrent of machine-gun fire follows the explosions, with infantry fire rattling in between. And all the while new troops march, drive, ride down Ludwigstrasse with mortars, artillery, forage wagons and field kitchens, sometimes accompanied by music, and a medical train has stopped at the Siegestor, and heavy patrols and various weapons divisions are scattering through the streets, and crowds of people form on every corner that provides cover but also a view, often with opera glasses in their hands.

The reader’s attention is drawn dynamically from the airplanes above to the masses of troops below; our gaze sweeps over the multitude of weapons, people, and vehicles, coming to rest on the clusters of bystanders taking in the spectacle through opera glasses. Klemperer memorably conveys the theatricality of the political events, the element of drama about them. In fact, he considers this a defining characteristic of the Munich revolution: “In other revolutions, in other times, in other places,” he writes in early February 1919, “the leaders have come from the streets, from the factories, from the typing pools of editorial and law offices. In Munich, many of them have come from the bohemian world.” Under these circumstances, politics appears to be not a profession but rather a stage upon which dreams (and nightmares) are played out. “I’m a visionary, a dreamer, a poet!” the prime minister Kurt Eisner cries out to a large assembly in the Hotel Trefler. Klemperer looks on in astonishment as Eisner – a “delicate, tiny, frail, stooped little man” in his eyes – elicits clamorous applause from the Munich audience, and he infers that the people of Munich are less interested in politics than in entertainment.

This book is unique in that it superimposes two time periods: the contemporary reports from Munich are supplemented with retrospective passages from Klemperer’s memoirs. Klemperer’s experiences in Munich are thus placed in their biographical and historical context. The result is a much deeper reflection on the time; aspects of the Munich revolution that sometimes seem absurd to the young man living through them in the spring of 1919 are later viewed in a more tragic light by the persecuted Jew in Nazi Dresden. Looking back, Klemperer recognizes the growing virulence of the burgeoning anti-Semitism in postwar Germany. “I do not want to exaggerate: there were a good many lecturers and students in Munich at the time who very much condemned this eruption of hostility toward Jews, and during my entire time in Munich I was never personally subjected to anti-Semitism, but I did feel depressed and isolated by it.” This book is essential reading.

ChristopherClark May 2015

Notes on the text

1919, writing as “Antibavaricus”

The two-column reports were written by Victor Klemperer in Munich as the revolution was taking place, between February 1919 and January 1920, under the pseudonym of “A.B. correspondent” (= Antibavaricus) for the Leipzig newspaper Leipziger Neueste Nachrichten. The majority of these articles are published here for the first time. The newspaper was only able to print one out of three dispatches; in the tumult of the revolution, the others either arrived too late or never reached their destination at all.

1942, looking back on the revolution

The texts set normally were written in 1942 as part of Klemperer’s memoirs. They were not included in the collection Curriculum vitae: Erinnerungen 1881–1918 (1989) because they were originally intended to be part of a longer chapter called “Privatdozent” (“Lecturer”), one which remained unfinished after Klemperer was abruptly forced to stop writing in 1942 – when the danger that the Gestapo might discover the manuscript had grown too great. These texts have never been published before.

Politics and the Bohemian World

(From our A.B. correspondent)

Munich, in early February [1919]

The Munich puzzle. – The ur-Bavarians Eisner, Mühsam, and Levien. – The political bohemians. – The communist estate with two kinds of love. – The effect abroad. – Eisner’s future prospects.

Munich politics have gone the way of Munich art – you find yourself asking: where are the Munich natives, or the Bavarians? In the arts you would come across names from East Prussia, from Württemberg, names from everywhere – but it was still “Munich” art. And in politics today? It is really not necessary to insinuate that the prime minister is a Galician and cast doubt on his German name.1 He is by his own admission a Prussian, and a Berliner to boot. And his main opponents on the Left, who are as highly esteemed in some circles as Eisner2 himself – and he is esteemed, even today, though the elections3 have gone somewhat against him! – even his radical opponents are no more Bavarian than he is. Erich Mühsam,4 the noble anarchist, whose star ascended in the Café des Westens in Berlin and long radiated a soft literary glow in Munich (despite so many noble anarchist lights) before taking on a truly bloody political flush – Mühsam, who by nature was always a benign, helpful, unmartial creature, and whose revolutionary heroism might amuse us even today were it not also perplexing and dangerous, is widely known to have his roots in Berlin’s west side5 – ever since he was transplanted there, that is. He grew up as the son of a Lübeck pharmacist in what was, at the time, a quiet Hanseatic city.

The latest figure to appear is Doctor Levien6 – as reported from Munich, Dr. Levien was recently arrested7 – who plays the most serious role here in the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council8 and on the Spartacists’ side, and who makes the government, which naturally does not want to create any martyrs, more than a little uneasy. To be clear from the outset: Doctor Levien is not a Russian Jew – he has Germanic blood in his veins, he shakes a mane of blond with every vigorous gesture, his eyes flash blue, and his left hand tugs the button nearest his heart on his field-grey uniform when, with his right hand thrust up or out, he refutes the objection that he is a foreigner who should have no say in matters. At least, this is how he appeared and sounded to me at an assembly where he thundered against the “reactionary” Eisner. Admittedly, when he then cast the poor, hereticized Bolshevists in the right light (namely, the gentle, rosy light of human benefaction) and suddenly faced the accusation that he seemed to be exceedingly familiar with Russian affairs, he thundered with the same conviction and emphatic gesticulation as before – only this time, instead of “I served on the battlefield as German!” it was “I was born in Russia!” So there is something slightly amiss with the Bavarianness of this leader of the people, too. No, he was born the son of a German in Russia, he first breathed Russian air, and he was soon to breathe Russian prison air. He was caught up in the Russian revolutionary movement at a tender age, he formed close ties with a Russian revolutionary in prison and later went to Zurich with her. The two studied and lived entirely in the peculiar atmosphere of Russian Switzerland – there have always been a Russian and an English Switzerland amidst the more well-known German, French, and Italian parts of the country. Just before the war, it occurred to Dr. Levien that he would have to fulfill his German military service obligation at the last minute if he did not want to lose his German citizenship. A friend described Munich to him in alluring terms, so he joined the “Lifers”9 here – and then the war broke out. For a little while he really did serve on the battlefield, and he was even slightly wounded, but he then spent a long time with the rear echelon in the East and at home. It’s said that he was brought back here because he was too closely connected to the Bolshevists in the East. And now he is Munich’s most radical popular leader.

The Munich puzzle: The Bavarian is so proud of his heritage, so averse to all things foreign, and particularly all things Nordic, which he likes to refer to collectively as “Prussian.” Yet who rules now, each in his own circle, but Messrs. Eisner, Mühsam and Levien! A very simple solution to this puzzle has been proposed. They’ve said of Eisner (and it’s all the more true of Levien) that he prevails in Munich because he feuds so fiercely with Berlin. There is certainly something to this. Eisner has – several times, in any case – appealed strongly to Bavarian particularism; and when Levien rages against the bloodhounds Ebert10 and Scheidemann,11 who have now been joined by the chief bloodhound Noske,12 he rages against murderous Berliners and bloodthirsty Prussians. Nonetheless, both men are so entirely un-Bavarian in their character and, above all, in their dialect – something tremendously important here – that anti-Prussianism alone cannot explain the possibility of their leadership.

No, Munich politics are like Munich art: you need not be either a native Bavarian or a native of Munich to participate. And this is not just a comparison – in Munich, art and politics are the same thing! This, then, is the solution to the puzzle. In other revolutions, in other times, in other places, the leaders have come from the streets, from the factories, from the typing pools of editorial and law offices. In Munich, many of them have come from the bohemian world. We just have to take into consideration – and here’s a job for future cultural historians and novelists – that the concept of bohemianism, its ambit, expanded during the war. Before 1914, bohemians were poets or painters or journalists or musicians. And even today they are all of these things, either by profession or avocation. But now they have also become politicians, economists – to put it more simply and clearly: they’re also very interested in contraband and profiteering, they’ve taken an interest (mostly negative) in the relationship between the individual and the masses, they’ve generally turned their attention, as it were, to the things outside the arts and culture section of the newspaper that they had previously scorned as being unaesthetic. The connection between the bohemian world and politics is as close as can be here in Munich. Is Eisner not thoroughly bohemian, does he not consider himself an artist and writer, as he himself repeatedly insists? But the people of Munich do not demand that their bohemians be Bavarian; perhaps they think true Munich blood is too good for this crowd. The bohemians of Munich are a foreign legion, kept for the amusement, the fun of the citizens of Munich. And now artistic amusement has been replaced by political fun …

This all sounds very comical and very exaggerated. But anyone who gives it serious thought will find it’s not such an exaggeration after all, that I have merely highlighted, isolated, divested of all incidentals, laid bare and thus – to speak in the inviting aesthetic manner – stylized one central aspect of the local political scene. And as far as comedy is concerned, there’s certainly an overabundance. In one of these expanded bohemian circles, from which a well-trodden path leads straight to Eisner’s office, an amiable, fresh-faced blond lad recently told me, “We’re communists, we bought an estate near Augsburg in order to farm it and prove that we can lead an idyllic life in a new community, peacefully, without money.” I asked whether one could join by contributing to the investment costs – by buying one’s way in, so to speak, as in a cooperative. No, it couldn’t be done with money. “So how did you do it?” – “We borrowed it, we don’t actually own anything ourselves, we’ve been good friends for a long time, and if someone has a benefactor he helps out the others.” – “Are there farmers in your group?” – “One woman is a gardener; the rest are students, merchants and what the bourgeoisie calls the ‘derailed.’” – “So there are women in your community, too?” – “Two so far.” – “What’s your communism’s position on women?” – “We reject legitimate marriage as paid prostitution. Other than that, there are two schools of thought which are still fighting it out. One wants couples to cohabit freely, along the lines of old common-law marriage. The other wants to overcome sexuality entirely; it won’t be important anymore.” – “How so?” – “We all live in friendly, unsexual fellowship; if the beast stirs in two people, they simply feed the beast and everything goes back to how it was. It’s inconsequential, inessential, a triumph over the carnal. That’s what we progressives think. But as I said, opinions still differ on this.” – “And where do the two ladies in your community stand?” – “The gardener belongs to the older school of thought, the student to the new one”…

Granted, this is very comical and it’s just one example of many. But there is a deadly serious side to this intertwining of bohemianism and politics. For instance, an Italian journalist, a reporter for a large newspaper, traveled from Innsbruck to Munich and now wanders around here freely in order to report on German attitudes and circumstances. He doesn’t understand German, but some people in the bohemian circles here understand Italian. The man has acquired a helpful guide from this circle, and it is in this circle that he gathers his impressions, which he faithfully reports back to Turin. I was there when an enthusiastic Spartacus man explained the German situation to him at the tea table: We must and will bring about the dictatorship of the proletariat. It just requires a little educational work. Then all of the imbecile tradesmen, farmers, doctors, academics – in brief, everyone who currently calls themselves bourgeois – will realize with astonishment and delight that they are not bourgeois at all, they are actually proletarians themselves, so they are destined to partake in the unjustly feared and ill-reputed dictatorship of the proletariat. We have at most 100,000 members of the middle class, bourgeoisie and capitalists in Germany. They bought off some of the herd that elected the reactionary National Assembly and kept the rest in stupidity and ignorance. The dictatorship is directed only against these 100,000, and if a little more blood should flow – well, a few drops more or less makes no difference. We have to follow through to pure socialism, like the exemplary Bolshevists who have simply been smeared by the lying press … All of this over tea, all of it in very passable Italian, all of it directed at readers abroad …

Incidentally, it is this more radical section of the political bohemian world that Kurt Eisner will have to thank if – and this is a very real possibility – he should remain at the helm after the state assembly13 has convened, although the distribution of votes is not to his advantage. He has already shifted somewhat to the right in order not to ruin his chance of continuing to govern from the outset. He also faces fierce enough opposition from the Spartacist quarter. But despite all the hostility, he gets along with these radicals because they are united by their background, their former circle – their bohemianism. So some kind of peace can probably be maintained if Eisner, even a more moderate Eisner, remains in power – but there could never be a moment of peace between any of the bourgeoisie and Munich’s bohemian radicals. If Eisner stays, he can thank Levien and Mühsam for it. Their opposition has pushed him closer to the bourgeoisie. At the same time, the bourgeoisie views Eisner as a shield between them and the group around Levien and Mühsam, who feud with him but do not seriously attack him. They feel too much affinity with him for that. They are hostile brothers, but they are brothers all the same – in bohemianism.

1.

Reference to the anti-Semitic attacks leveled against Kurt Eisner in rightleaning bourgeois newspapers.

2.

Kurt Eisner (1867–1919), journalist and politician; editor of

Vorwärts

, the newspaper of the Social Democratic Party, from 1898 to 1905. He joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) in 1917 and played a leading role in bringing down the Bavarian monarchy. Eisner served as chairman of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council and was elected prime minister of Bavaria on November 8, 1918. He proposed a “realpolitik of idealism” and tried to combine the councils system with parliamentarianism.

3.

Reference to the elections to the constituent Bavarian State Parliament, which were held on January 12, 1919; see also note 13.

4.

Erich Mühsam (1878–1934), writer and politician; member of the Central Council of the Bavarian Council Republic in 1919. He was arrested after the defeat of the republic and sentenced to fifteen years in prison, ultimately serving nearly six years of his sentence. Mühsam was arrested by the Nazis in 1933 and murdered in the Oranienburg concentration camp in July 1934.

5.

The west side of Berlin was a sought-after address for journalists, writers and artists.

6.

Max Levien (1885–1937), co-founder of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in Munich in 1919 and editor of the Munich edition of

Die Rote Fahne

(The Red Flag). As a member of the Executive Council from April 13, 1919, he was one of the leaders of the Bavarian Council Republic along with Eugen Leviné. He was arrested in Vienna on October 7, 1919, but was not extradited to Germany. From June 1921 he lived in the Soviet Union, where he worked as an editor and lecturer in Moscow, among other activities. He was arrested again during the Stalinist purges in December 1936 and sentenced to five years in a prison camp in March 1937. On June 16, 1937, his punishment was changed to a death sentence and carried out immediately.

7.

Max Levien was one of many leaders of the Left who were arrested on January 10, 1919; protesters forced their release the following day. Levien was arrested and briefly held again on February 7, 1919.

8.

At the end of 1918, revolutionary workers and soldiers joined forces to form workers’ and soldiers’ councils which functioned as revolutionary governing bodies, replacing the old governments at the local, regional, and national levels.

9.

Leiber

: popular name for the members of the Bavarian Infantry Lifeguards Regiment.

10.

Friedrich Ebert (1871–1925), Social Democratic politician, chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1913 (together with Hugo Haase until 1915), chairman of the SPD parliamentary group from 1916 to 1918 (together with Philipp Scheidemann). During World War I he was a proponent of the

Burgfrieden

policy (a truce between domestic political parties to support the war effort) and of a negotiated peace settlement. On November 10, 1918, he assumed joint chairmanship of the Council of People’s Deputies with Hugo Haase and, with the support of the army, fought all attempts to establish a councils system in Germany. He served as Reich president from 1919 until his death.

11.

Philipp Scheidemann (1865–1939), Social Democratic politician who followed the moderate line of the majority of his party during World War I. He was appointed a minister without portfolio in the government under Prince Max von Baden in 1918. On November 9, 1918, he proclaimed the German Republic and became a member of the Council of People’s Deputies. From February to June 1919 he served as chancellor, heading the Weimar Coalition made up of the SPD, the Center Party, and the German Democratic Party (DDP).

12.

Gustav Noske (1868–1946), Social Democratic politician, responsible for military affairs as a member of the Council of People’s Deputies (December 1918–February 1919). The January uprising of the Spartacists in Berlin was suppressed under his leadership. Noske served as Reich Minister of Defense from February 1919 to March 1920.

13.

Reference to the new constituent Bavarian State Parliament elected on January 12, 1919. The Bavarian People’s Party won 66 of the total of 180 seats, the SPD 61, the DDP 25, the Bavarian Peasants’ League 16, the National Liberal Party 9 and the USPD 3.

Revolution

[November 1918]

I slept undisturbed until the early morning, when we reached the German border.14 From that point on I had changing and diverse company throughout the day: civilians, soldiers from different units, sailors. Everyone talked about the revolution, of course, and I was able to gather from all the stories that it hadn’t gone as peacefully everywhere as it had in Leipzig and Wilna; most people also thought that the real trouble still lay ahead of us, that there was no way the Spartacus group would give up without a fight. Two sailors were certain something would happen the next day in Berlin. I told them I intended to spend the night there, in part to visit my relatives,15 in part to avoid waking my wife.16 “You’d be better off traveling straight through,” they said. “Who knows if you’ll be able to get a train tomorrow?” So I switched directly from the Friedrichstrasse to the Anhalter station; a chatty old porter carted my luggage to the tram on Dorotheenstrasse and pointed out houses where shots had been fired. “I had a cartload, and suddenly a machine gun goes off. So I duck into a hallway, and shots start coming from the other side, too, and people crawl in from the tram – it was a real scramble. Afterwards they hauled out three officers and a few of the youth militia and put ’em right up against the wall and threw ’em in the Spree.”

I had assumed that after stopping over very briefly I would travel on from Leipzig and report to the Munich regiment.17 But on this informative journey, I also learned that one could no longer assume a soldier would to try to reach his specified destination; once you had slipped the grasp of your company or battery you could go anywhere, and as long as you didn’t make any demands for pay or plunder, you could consider yourself discharged – because which authority would really want to fish around for a single person in the general chaos? Neither of us wanted to go to Munich, and we would arrive early enough for the start of the semester; and besides, I liked to have my military papers in order, so I decided to try to arrange my discharge from Leipzig. I would say that important family and professional matters tied me to Leipzig for a time. But it initially appeared as if this wouldn’t work. At the railway station command post and at headquarters, which I visited one after the other, I found the same situation: clusters of men in field-gray uniforms crowded around the desks of common soldiers with red armbands. The soldiers scribbled relentlessly, and every now and then, without looking up or putting down their pens, they would refuse and rant, rant and refuse. The surrounding clusters of men ranted right back, of course – it was an ongoing spectacle. “All they’re doing,” one of the rejected men told me, “is writing out tickets to the reserve unit and refusing home leave. They’re sworn to this yes-and-no and you can’t get anything else out of them. No exceptions.” Resigned, I left. On the stairs I encountered a private, an older man with the look of an intellectual. He must have held some office in the revolutionary administration because he, too, wore the red armband. “Comrade,” I said, “nothing can be done in there, they’re just following procedure – can you help me?” And I briefly explained what I wanted. “You can do that,” he replied. “Write it up as a petition to the Bavarian Ministry of War and bring it to me this afternoon in the information office at the railway station – Private Hermann.” Once there, he wrote “Promptest attention requested by the Leipzig Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council” at the bottom of my page, stamped the petition and envelope, stamped my ticket as well and issued ration coupons to me on it “until further notice.”

Now I could spend a few weeks living in the old way, in my old social circle18 – but even better than before! The war was at an end, I was really free to do my work, and it had a sure objective, because even though I pinned little hope for the future on my Munich lectureship,19 at least it definitely belonged to me and couldn’t slip through my hands like the professorship in Ghent.20 And the revolution wouldn’t bother me. I wanted to work, just work, return to L’Astrée,21 prepare a large course of lectures on literary history. On the whole I managed to do this, but the revolution could not really be shut out; it was always there, from morning to evening. In the morning, my barber told me how many rifles he had bought, ten marks apiece, from soldiers who were disarming on their own initiative, and how he could easily unload the weapons for twice the price. In the evening, I went to a lecture at the Modern Languages Society. Becker,22 still very friendly, had personally invited me. I wore my uniform; there was no obligation to salute and no curfew anymore, and civilian clothing had to be spared. On the stairs an agitated student approached me, wanting to know whether I was part of the Soldiers’ Council, whether I had come to confirm that the event was innocuous. The lecture had been prohibited an hour previously, access to the building had been blocked by the military, and the erroneous order had only been lifted twenty minutes earlier after entreaties by telephone. The Soldiers’ Council had sensed a counter-revolutionary gathering was in the works, as there had recently been a quarrel about hoisting the red flag over the university and the rector had stepped down. Afterwards, Becker – speaking in French, which flowed more smoothly from his lips than German – gave an entirely unpolitical commentary on three symbolic poems by Victor Hugo in front of a handful of students and teachers. Incidentally, this was the first time I heard about the academic situation in Dresden, with which I was completely unfamiliar. For his lecture, Becker handed out a sheet with the three Hugo poems as if they were the lyrics of a concert program. The pages had originally been printed for a summer course in Dresden which had been thwarted by the war. There was a technical college there with all sorts of literary and philosophical ambitions, even with a proper chair of Romance philology. The occupant of this chair, Heiss,23 had been sent to Dorpat in some administrative capacity during the war, and Becker had stood in for him in Dresden. These fleeting reminders of the revolution, such as the barber dealing in arms or the fear of sedition in the Modern Languages Society, cropped up day in and day out, and I learned from the newspapers and my conversations with Harms24 and Kopke25 that tensions were growing all over Germany, and that people everywhere, Leipzig included, were expecting civil war to erupt at any moment. But Harms and Kopke viewed the situation very coolly, as if with purely professional interest, and Hans Scherner,26 who had always been apolitical, was entirely absorbed in his studies for his matriculation exam,27 and my wife spent every remaining hour that was granted to her in Leipzig thinking fervently about her organ studies.28 So I, too, pushed away all emotions and distractions and focused all the more intently on preparing for my teaching position, since people were now starting to talk about special courses for students returning home from the war. Only once did I attend a political gathering; I wanted to get to know the most radical of them all. The Spartacus people met in the Coburger Hallen, a rather dismal tavern on the Brühl. Judging from the pictures on the wall, the long, smoky room had been the meeting place for a railroad workers’ association; above the many group photos of engineers and conductors hung a large portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm29 with his cuirassier helmet and his Haby mustache.30 About 250 people sat tightly packed at two long tables, smoking and drinking beer, most of them men of various ages, the majority probably workers. The scene was so utterly peaceful that it could well have been a regular meeting of railroad workers, or a presentation by a rabbit breeders’ club or group of amateur gardeners. Even the speaker’s matter-of-fact tone fitted with this supposition, as long as you listened only to the sound of his slow, deliberately formed sentences. Their content therefore affected me all the more. The speaker, a hulking soldier of about forty, East Prussian judging by his accent, proved to his silent audience the necessity of civil war, just as a schoolteacher would develop a mathematical theorem. “We are the poor,” he said, “and the uneducated. The revolution has not helped us at all, a bourgeois republic has been created, the government socialists have betrayed us – they are at least as hostile toward us as the other parties on the Right. The press belongs to the propertied and educated classes; under the universal freedom of the press, we alone are not free. The propertied and educated classes will make up the majority of the planned National Assembly;31 we will be in the minority and have just as little influence there as we now have in the press. There is no universal freedom that can help us, at least not for the time being. We must prevent the formation of the National Assembly, we must take the press entirely into our hands and only our hands, we must establish and maintain the dictatorship of the proletariat until all property has been socialized and until we get the education we have been denied. This can only be achieved by force. And why shouldn’t we use force? So much blood has been spilled for the capitalist cause, why shouldn’t a little flow for the proletarian cause as well?” The audience nodded, shouted bravo, applauded, all very seriously, with conviction, and without overexuberance. A second speaker, this time a civilian, undoubtedly a local master craftsman, began to paraphrase the remarks of the East Prussian. “Abominable waste of time,” I thought, and I left. I did not sympathize in the least with these people. I hoped that the government would succeed in keeping them in check without bloodshed. But if it were not possible without violence, well, then hopefully the government was strong enough to assert itself and follow through on the election of the National Assembly. What the Spartacist had decried as bourgeois freedom was, to me, the epitome of all that was politically good, and it had to meet the needs of everyone, even the proletarian worker – and freedom could only spread to an entire people if it came from the center. Perhaps the revolution had come at an unfortunate time, but I wholeheartedly approved of the new government’s principles (just as I still love the Weimar Constitution to this day).32 If I did have any sympathy for the opponents of the republic, it was only with respect to the opposition on the Right. We had to endure such terrible things from our adversaries; perhaps without the revolution we would not have been quite so defenseless against them after all. Could it possibly have been avoided without an internal collapse? “In Aachen (or in Jülich),” I noted, “a Belgian commander decreed that German civilians must honor the officers of the occupation by stepping from the sidewalk and doffing their hats, under penalty of summary execution. Granted, this summer Beyerlein33 told me we did the exact same thing in Romania, and today Kopke said, ‘In Poland, too’ – but it makes me quite miserable to think of this humiliation.” But if I sympathized a tiny bit with the opposition on the Right, it was in the belief that they posed no threat to the new system of government. I thought that they would form the right wing of the National Assembly, not try to demolish the republic. But it was not hard for me to push all of these thoughts aside and devote myself entirely to pre-Classical and Classical French literature. For all of the editorials and assemblies, Leipzig was deeply serene, and in Café Merkur the rustle of newspapers mixed with the slap of skat cards. Of course, my devotion did not entirely cut me off from the present. “The cruelties of the French!” I wrote in another diary entry from the time. “How is it possible that one and the same people can behave in such a cruelly vindictive and ignoble way and yet produce such gloriously humane literature?” This was the question that would shape the development of my program of literary history and Kulturkunde34 (the word was still unfamiliar to me, and to this day I do not know when it was first used, or by whom) in the coming years.

In mid-December I traveled to Munich – alone, and hoping to stay for just a few days. I had four items on my agenda, but a fifth, unforeseen one subsequently proved to be the most significant. On the journey there I first experienced what would become my principal memory of all trips taken during the revolutionary period: I couldn’t find a way onto the overcrowded train through the regular door or completely blocked corridors, but there were always some fellows standing around in uniform or civilian dress who would hoist me up to a window or bundle me out of one. The first time this happened, on the evening of December 10th in Leipzig, was the snappiest and most in keeping with the style of the revolution: two sailors hauled me aboard with a loud “heave-ho!” and a single jerk. Of the many different scenes that played out on the long, frequently delayed journey, two stayed with me. An old Saxon reservist ruefully contended that Germany was suffering the misery of the revolution on account of its sins. He was laughingly contradicted by a cocky lad from Hamburg, the most vivid caricature of a revolutionary I had ever seen. His unruly blond mane tumbled into bold blue eyes, and his neck bore a gaping red scar that could just as easily have been acquired in a dockside brawl at home as on the front line. A red band was tied around the arm of his uniform jacket, and across his chest he wore a sash more than a hand’s breadth wide, the ends of which hung down over his belt. The boy said the revolution was a joy and a salvation. He himself was taking a study trip through Germany to see where it was proceeding most efficiently. He boasted of getting a free ride wherever he went, as there was always a soldiers’ council willing to give him train tickets, accommodation and food. The other scene, which unfolded on the Bavarian side of the border the next morning, seemed to have come straight from a prenaturalist comedy. A white-haired Swabian uncle had picked up his two nieces from boarding school and was taking them home. He wanted to protect the innocents, but he also had to guard the luggage stowed in the lavatory. In his absence, the high-spirited girls took the opportunity to befriend some jocular soldiers, who gave them cigarettes and a light. The girls laughed, smoked and coughed, the soldiers teased, the old man pleaded and scolded, then disappeared mid-sentence because he feared for the luggage, then returned, agitated, to implore and rebuke them some more. Munich, which I reached at noon the next day, three hours late, presented the most surprising scene of all. How often had I compared Leipzig’s teeming life with Munich’s parochial drowsiness in my diary in recent years. But now! If I might be forgiven a paradox, I would write that now things were entirely the other way around: Leipzig was in a state of the soberest tranquility, while Munich at first glance was a vision of the extraordinary, the colorfully and passionately romantic. The city was richly decked with multicolored flags. Bavarian blue and white prevailed, but black and yellow (Munich’s city colors) and the black, red, and gold of Greater Germany and the republic were not uncommon and roughly balanced