0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

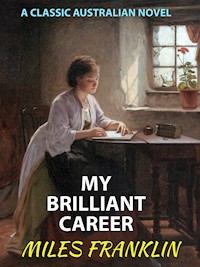

My Brilliant Career is a 1901 novel written by

Miles Franklin. It is the first of many novels by Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879–1954), one of the major Australian writers of her time. It was written while she was still a teenager, as a romance to amuse her friends. Franklin submitted the manuscript to Henry Lawson who contributed a preface and took it to his own publishers in Edinburgh. The popularity of the novel in Australia and the perceived closeness of many of the characters to her own family and circumstances as small farmers in New South Wales near Goulburn caused Franklin a great deal of distress and led her to withdrawing the novel from publication until after her death.

Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (14 October 1879 – 19 September 1954), known as Miles Franklin, was an Australian writer and feminist who is best known for her novel My Brilliant Career, published by Blackwoods of Edinburgh in 1901. While she wrote throughout her life, her other major literary success, All That Swagger, was not published until 1936. Shortly after the publication of My Brilliant Career, Franklin wrote a sequel, My Career Goes Bung, which would not be published until 1946.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Miles Franklin

My Brilliant Career

The sky is the limit

Table of contents

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

I Remember, I Remember

An Introduction to Possum Gully

A Lifeless Life

A Career Which Soon Careered To An End

Disjointed Sketches And Grumbles

Revolt

Was E’er a Rose Without Its Thorn?

Possum Gully Left Behind. Hurrah! Hurrah!

Aunt Helen’s Recipe

Everard Grey

Yah!

One Grand Passion

He

Principally Letters

When the Heart is Young

When Fortune Smiles

Idylls of Youth

As Short as I Wish had been the Majority of Sermons to which I have been Forced to give Ear

The 9th of November 1896

Same Yarn—continued

My Unladylike Behaviour Again

Sweet Seventeen

Ah, For One Hour of Burning Love, ’Tis Worth an Age of Cold Respect!

Thou Knowest Not What a Day May Bring Forth

Because?

Boast Not Thyself of Tomorrow

My Journey

To Life

To Life—continued

Where Ignorance is Bliss, ’Tis Folly to be Wise

Mr M’Swat and I Have a Bust-up

Ta-ta to Barney’s Gap

Back at Possum Gully

But Absent Friends are Soon Forgot

The 3rd of December 1898

Once Upon a Time, When the Days Were Long and Hot

He that despiseth little things, shall fall little by little

A Tale that is told and a Day that is done

PREFACE

A few months before I left Australia I got a letter from the bush signed “Miles Franklin”, saying that the writer had written a novel, but knew nothing of editors and publishers, and asking me to read and advise. Something about the letter, which was written in a strong original hand, attracted me, so I sent for the MS., and one dull afternoon I started to read it. I hadn’t read three pages when I saw what you will no doubt see at once—that the story had been written by a girl. And as I went on I saw that the work was Australian—born of the bush. I don’t know about the girlishly emotional parts of the book—I leave that to girl readers to judge; but the descriptions of bush life and scenery came startlingly, painfully real to me, and I know that, as far as they are concerned, the book is true to Australia—the truest I ever read.

INTRODUCTION

Possum Gully, near Goulburn,

I Remember, I Remember

“Boo, hoo! Ow, ow; Oh! oh! Me’ll die. Boo, hoo. The pain, the pain! Boo, hoo!”

An Introduction to Possum Gully

I was nearly nine summers old when my father conceived the idea that he was wasting his talents by keeping them rolled up in the small napkin of an out-of-the-way place like Bruggabrong and the Bin Bin stations. Therefore he determined to take up his residence in a locality where he would have more scope for his ability.

A Lifeless Life

Possum Gully was stagnant—stagnant with the narrow stagnation prevalent in all old country places.

A Career Which Soon Careered To An End

While mother, Jane Haizelip, and I found the days long and life slow, father was enjoying himself immensely.

Disjointed Sketches And Grumbles

It was my duty to “rare the poddies”. This is the most godless occupation in which it has been my lot to engage. I did a great amount of thinking while feeding them—for, by the way, I am afflicted with the power of thought, which is a heavy curse. The less a person thinks and inquires regarding the why and the wherefore and the justice of things, when dragging along through life, the happier it is for him, and doubly, trebly so, for her.