Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Northern House

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Nameless Country gathers poems by the Scottish-Jewish poet Arthur 'A.C.' Jacobs, whose work, somewhat critically neglected in the past, has gained new resonance for twenty-first-century readers. Writing in the shadow of the Holocaust, Jacobs in his poems confronts his complex cultural identity as a Jew in Scotland, as a Scot in England, and as a diaspora Jew in Israel, Italy, Spain and the UK.A self-made migrant, Jacobs was a wanderer through other lands and lived in search, as he puts it, of the 'right language', which 'exists somewhere / Like a country'. His poems are attuned to linguistic and geographic otherness and to the lingering sense of exile that often persists in a diaspora. In his quiet and philosophical verse we recognise an individual's struggle for identity in a world shaped by migration, division and dislocation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 69

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

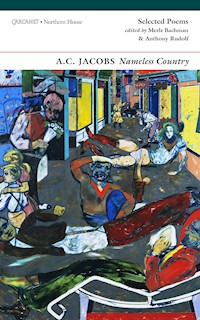

Nameless Country

SELECTED POEMS OF A.C. JACOBS

edited by Merle L. Bachman and Anthony Rudolf

Northern House

Contents

Acknowledgements

The Editors gratefully acknowledge the permission of Sheila Gilbert, Literary Executor to A.C. Jacobs’ estate, to publish the work herein, including archival materials.

The Editors also wish to thank Ms. Joanne C. Fitton, Head of Special Collections, and the staff of Special Collections in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds, where the Archive of A.C. Jacobs’ work is located. They kindly provided the photographs of manuscript material used herein, which can be found on pp. 2, 16, 50, 68 and 94. These materials are from MS 2065/1, Boxes 2 and 5 and are reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library.

The Editors also gratefully acknowledge Sheila Gilbert for providing and permitting the publication herein of selected photos of A.C. Jacobs from her personal archive, which can be seen on pp. 1, 15, 43, 49, 67 and 93. Further, we thank Gerald Mangan for permitting the publication of his sketch of A.C. Jacobs as the book’s Frontispiece as well as the photo he took of Jacobs that appears on p. 44.

*

In addition, Merle Bachman adds:

I wish to thank Sheila, Arthur’s sister, for her kindness in allowing visits to Arthur’s archive when it was still located in her home, and both Sheila and her husband Geoffrey Gilbert for conversation, cups of tea, lifts to the tube station and, in general, their interested support in the research that led to this book. Deep thanks and gratitude also to Anthony Rudolf, without whom I would never have met Sheila, and for being such a wise, encouraging and supportive colleague from the very beginning.

Further thanks go to Spalding University for professional development funding that helped cover the costs of travel; to Peter Lawson and the Open University for accepting my paper on A.C. Jacobs’ ‘diasporic poetics’ for the British Jewish: Contemporary Culture conference in July 2015, and then publishing it in article form in the July 2016 issue of The Journal of European Popular Culture (7:1); and to Alan Golding (University of Louisville) and Kathryn Hellerstein (University of Pennsylvania) for important conversations, and to Shachar Pinsker (University of Michigan), for my talk at the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies in Fall 2015, half of which was on Jacobs’ poetry.

Introduction

Merle L. Bachman

1 A Man in Motion

While still a young man, the poet Arthur (A.C.) Jacobs wrote:

I could conceive of my life as no more than sequences of journeys, or perhaps journey within journey (archive).

Arthur Jacobs began his journeys in Glasgow, Scotland, where he was born in 1937 into an Orthodox Jewish family. His grandparents had done their own travelling, emigrating towards America from Lithuania, and finding themselves content to stay in Scotland. Arthur’s family moved to London, however, when he was a young teenager – one who was already beginning to regard himself as a writer. Growing to adulthood in England, yet holding fast to a Scottish identity, added another layer to the precocious poet’s sense of himself, as did his own travel to Israel, where he lived for three formative years in the early 1960s. When Arthur left for Israel, he had already forsaken the religious practices of Jewish orthodoxy, but he remained enmeshed all his life with Jewishness – its languages, history, and intellectual culture. The gift of his time in Israel was, ironically, that it sharpened his commitment to being a diaspora Jew with ‘access to three or four cultures’* – one who came to know modern Hebrew well enough that he could make a partial living from translating the work of Israeli writers.

After Israel, barely 30 years of age, he gave himself a middle name – ‘Chaim,’ the Hebrew word for life – and began to sign his poem drafts, ‘A.C. Jacobs.’

Journey within journey. I wanted to go to Edinburgh. The puzzle of Scotland moves me more than any other like it… Greyness and lost vigour. Very well, I am a romantic. A two thousand year old nostalgia seeps its melancholy through my veins… (archive). From Israel to London to Edinburgh, to the Scottish Borders, to London, and back again – his movement continued, interspersed with travels to Italy and especially Spain, the country that kindled in him new excitements, new perspectives on Jewish history. Jacobs’ choice in life as well as in writing was to remain at the borders, ever an insider/outsider, to reject ‘settling’ or settling down. While his restlessness might have cost him the sustained focus necessary to extend his body of work, it also fed the internal tensions expressed in his most powerful poems. His poetic persona is one that embraces the facts of his own marginality, as a Jew in Scotland, a Scot in England, an ‘Anglo-Saxon’ in Israel, and a diaspora Jew everywhere.

It was in Madrid, in 1994, at the seeming cusp of a new phase, that Jacobs’ journeys came to an end. He died suddenly, shortly before his 57th birthday.

Poetry, of course, has the capacity to live on. Over time, Jacobs had garnered poet colleagues, supporters and friends, starting when he’d been a young participant in meetings of Philip Hobsbaum’s ‘Group’ when it was based in north London. The poet Jon Silkin became an important mentor and friend. His poems and translations had appeared in a number of journals, including Stand and Ambit, and in two anthologies. Two modest collections of his work had been published: The Proper Blessing (his own poems) and The Dark Gate (translations from David Vogel), both in 1976, by Anthony Rudolf’s Menard Press. Tim Gee Editions also republished an expanded version of The Proper Blessing