4,56 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

A collection of six plays dealing with the new South Africa, published in 2006 to celebrate 10 years of democracy post-apartheid. Plays about racial conflict, the impact of AIDS, power and corruption, the legacy of the past and female identity. Reprinted 2012, 2019.

The Plays

The Playground by Beverly Naidoo

“…it floats on a haunting, echoing raft of traditional South African harmonies that make watching it a joyful experience as well as a thought-provoking one…” Time Out Critics’ Choice – Pick of the Year

Taxi by Sibusiso Mamba: Edinburgh fringe first winner

“a superbly written and produced play… A fine piece of work that’s refreshingly free of cliches.” Daily Mail, Pick of the Week

Green Man Flashing by Mike Van Graan

“…This finely crafted drama tears at the heart and soul of our democracy, and rips at the underbelly of corruption and political power through its astute writing…” Star Tonight

Rejoice by James Whylie

“… the cruellest irony of all is left until the end… the same one which has spelled the death of Rejoice… And millions more.” Friends of BBC Radio 3

What the Water Gave Me by Rehane Abrahams

“tales that retrieve ancient magics and reveal contemporary terrors…” Cape Times

To House by Ashwin Singh: Finalist in the 2003 PANSA (Performing Arts Network of SA) Festival of Reading of New Writing (the country’s foremost playwriting contest)

“To House is an important piece of theatre; in it people voice opinions that are uncomfortable and edgy. The cathartic and therapeutic value of hearing these things said aloud in a public place is part of our essential healing process and proves, once again, that art has the ability to go where angels fear to tread.” Daily News, Durban

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

NEW SOUTH AFRICAN PLAYS

edited by Charles J. Fouriewith a foreword by Gcina Mhlophe

Rehane AbrahamsSibusiso MambaBeverley NaidooAshwin SinghMike van GraanJames Whyle

First published in 2006 by Aurora Metro Publications Ltd. 67 Grove Avenue, Twickenham, TW1 4HX, UK.

Facebook @AuroraMetroBooks

Twitter @AuroraMetro

Production Editor Gillian Wakeling / Peter Fullagar

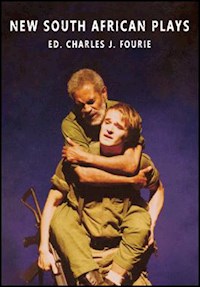

Cover photo of Wyllie Longmore and Oliver Dimsdale in The Dead Wait, by Paul Herzberg, produced by Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre Copyright © Jonathan Keenan 2006

Introduction Copyright © Charles J. Fourie 2006

Foreword Copyright © Gcina Mhlophe 2006, South Africa My Land first published in Freedom Spring: Ten Years On, Editor Suhayl Saadi (Glasgow City Council) 2005

With thanks to: Claire Grove, Beverley Naidoo, Olusola Oyeleye, Adi Drori, Jacob Murray, Mannie Manim, Diana Franklin, Yvonne Banning, Michelle Knight, Africa Centre, South African High Commission

What The Water Gave Me Copyright Rehane Abrahams © 2006

The Playground – Copyright © Beverley Naidoo 2006

To House – Copyright © Ashwin Singh 2006

Rejoice Burning – Copyright © James Whyle 2006

Green Man Flashing – Copyright © Mike van Graan 2006

Taxi – Copyright © Sibusiso Mamba 2006

The authors’ have asserted their moral rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Caution: All rights whatsoever in these plays are strictly reserved. Application for performance, including professional, amateur, recitation, lecturing, public reading, broadcasting, television and the rights of translation into foreign languages should be addressed to:

The Playground c/o The Agency (London) Ltd, 24 Pottery Lane, W11 4LZ

What the Water Gave Me c/o The Mothertongue Project, PO Box 12561, Mill St, 8010, Cape Town, S.A.

Taxi c/o Micheline Steinberg Associates, 104 Great Portland Street, London W1W 6PE

For other plays, [email protected]

This paperback is sold subject to condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A Licence must be obtained from Phonographic Performances Ltd. Ganton Street, London W1, for music whenever commercial recordings are used.

ISBNS:

978-0-9542330-1-3 (Paperback) Printed by 4Edge Printers, Essex, UK

978-1-910798-89-8 (Ebook)

Foreword

This country of mine – I do not remember a time when I did not love it. From early childhood, when my grandmother used to say to me, “There is a bigger world out there”, I loved my little corner of it. From a time when she told me the ancient stories of my people, stories that taught my imagination to fly, images and songs and chants that were to stay with me all my life. Wisdom of our ancestors came through great sayings and idioms that are so African and yet so universal. My Gogo would say, “Hammarsdale is a small town; Durban, our city, is a small place in South Africa; South Africa is a small place in the continent of Africa and Africa is just one continent in a bigger world.”

In our South Africa, there are so many people who look at us and see only our mistakes and weaknesses. They see the drought-stricken land and rivers that have so little water most of the time. They look at the inequalities that have been inherited from a long merciless chapter of our lives and top it all with the levels of illiteracy and the newest monster to devour many of our young people, our very future – AIDS. What hope is there, they ask? One must long for the Americas, Australia and Europe – run there to the houses on top of the hill. Houses with golden windows, houses with tons of food, endless joy, free-flowing cash, possession and wide rivers.

I say this land of mine, South Africa, is the place for me. I see the golden windows in the eyes of my people. I see the fountains of hope in the energy that encourages us to keep on living, no matter how hard the times. I hear the engine that drives us, in the song of my people. I see the spirit of our ancestors in the faces of the community builders who have so little and yet find it possible to build and uplift others. I feel the love of my creator in the heat of the midday sun on a winter’s morning, and in the power of the ocean’s waves that surround us; the uniquely diverse natural beauty that is only South African. And I know this little part of the world is where I want to be.

Politicians and big businesses are doing their part. But my inspiration comes from everyday people.

Again, I turn to our ancient wisdom: Umuntu ufunda aze afe, simply meaning – a person learns until she dies. I am one who believes that we will keep on learning to do things in new ways. Yes, we will embrace modern technology and new democracies and the works. We will tackle the AIDS monster with even more vigor, more determination, than we used to fight Apartheid. It has been slow but I feel the momentum building.

But we will also find strength in the ways of this continent, ways that can guide us to strive for a better tomorrow, every single day. We are a nation of fighters and builders. And because we do not give accommodation to hatred in our hearts, we have come this far. Hope shines in our eyes and it shines like young love. Some people may wonder how we Africans can wake up and laugh with the sun, after all the rivers of tears we have been through. Easy – Hope, that’s the undying light that keeps us here.

In these past few years of our relatively new democracy, it has seemed like we are losing our focus at times but I know from experience that the road is steep and we are struggling. Some say the struggle is never over. I know too that it is small people with very little resources who are working like mad to improve the lives of their families, their neighbors and communities. I have been impressed by the ‘ordinary people who do extraordinary things’. Their invaluable efforts are the essential oil that turns the wheels of South Africa, my land, here at the very southern tip of the African continent. I look at them with admiration and from them I ask for the fire to light my own efforts.

Thank you.

Gcina Mhlophe

Extract from South Africa My Land

Contents

Introduction by Charles J. Fourie

THE PLAYS

What The Water Gave Me

Rehane Abrahams

The Playground

Beverley Naidoo

To House

Ashwin Singh

Rejoice Burning

James Whyle

Green Man Flashing

Mike van Graan

Taxi

Sibusiso Mamba

Useful Links

More from Aurora Metro

Introduction

Charles J. Fourie

An attempt to briefly reflect on the totality of South African theatre writing would lead one along diverse and never-ending paths. South Africa is as much a cultural prism as it is a rainbow nation, and this is true also of our theatre heritage which has seen many a season of change during the past few decades.

Our culture of resistance, which characterised the social and political landscape of the apartheid-years, mirrored these changes in many of the plays staged since the late 1950s. South African writers have consistently resonated the turmoils of our collective history in an attempt to awaken our social and political conscience.

Plays from this early era by writers such as Barney Simon, Athol Fugard, Gibson Kente, Bartho Smit, Andre P. Brink not only reflected the inner turmoil and conflict experienced by themselves as individuals, but also that of the diverse communties from which they came. As these writers explored the hopes and dreams of a people longing for freedom, they also voiced their fear, anger and frustration.

Censorship was the order of the day with many a playwright’s work banned because it dared to criticise the then ruling National Party regime, or otherwise ignored the laws of segregation which prohibited people of colour from performing on stage.

Plays performed at state-run theatres were surreptitiously submitted to a censorship board who literally ‘cleansed’ the scripts before they were allowed to perform them in front of an audience, forcing playwrights to compromise their work or suffer the consequences. This led to further resistance from these playwrights, who in turn sought out alternative venues to stage their works.

The Market Theatre in Johannesburg (started by the likes of Barney Simon, Mannie Manim and Vanessa Cooke) was to become home to many of these playwrights, who felt the need to be heard and seen beyond state control. Other initiatives such as the Space Theatre in Cape Town under the auspices of Brian Astbury, staged challenging work from daring writers such as Pieter Dirk Uys.

And, albeit far from the mainstream, protest theatre took on a momentum of its own in the townships, where playwrights like Gibson Kente devised much of their work, performing in community halls despite the lack of skills and infrastructure, offering audiences a chance to hear and see their own stories, performed by their own people.

To date, the works of Athol Fugard remain the most well-known South African export, but it would serve to note that other writers such as Paul Slabolepsky, Pieter Fourie, Mbongeni Ngema, Matsa-mela Manaka, and Maishe Maponye wrote seminal plays that wait to be discovered beyond our borders. So too, the works of Deon Opperman and Reza de Wet.

As the struggle for liberation drew to a close with the release of Nelson Mandela and the unbanning of the ANC in 1990, a new generation of playwrights would emerge whose aim it was to forge a common identity for all South Africans, and whose work one could describe as ‘voices of reconciliation and reason’.

The plays collected in this edition by no means aim to reflect the complete, and one might add, prolific output of new works by our playwrights over the past decade since the 1994 democratic elections. Other ground-breaking and important plays have been written by young playwrights like Brett Bailey, Aubrey Sekhabi, Sabata Sesui, Malan Steyn, Saartjie Botha and Harry Kalmer.

This explosion of new writing could not only be ascribed to the birth of our new nation, but also to the enormous growth of arts festivals. My guess is that at the Grahamstown National Arts Festival and the Karoo National Arts Festival alone, some twenty new plays are staged each year.

Other initiatives such as the Baxter Theatre’s Playground series of staged readings, the Market Theatre Laboratory and the Collaborations Festival at Artscape, have greatly contributed toward the development of our emerging playwrights. Three of the plays in this collection have their origins at such initiatives.

The opportunity for at least three of the plays included in this collection to be heard on radio for the first time, has also contributed to their further development. It is my firm conviction that if a play can succeed in holding an audience’s attention within the strict confines of radio broadcast, so too will it succeed on stage.

The Plays

Mike van Graan’s Green Man Flashing started as a radio play titled The Reunion and was later adapted for the stage as Slippery Slope. Collaborating with director, Clare Stopford, after a period of rigorous rewritings, the play finally made its way into the mainstream, where it played to instant success. Digging under the skin of contemporary South Africa as van Graan has done in previous plays, Green Man Flashing goes on to explore themes of sexual harassment, political loyalty and finally, accountance to truth, which has made it one of the most talked about plays in recent years to be staged in South Africa.

James Whyle’s Rejoice Burning is a powerful and humane drama which brings the issue of AIDS to the foreground as a universal theme, and one relevant to contemporary South Africa. In a subtle juxtaposition of black and white – the old world and the new converge around the tragic circumstances that face each of the characters. One is left with the question – who is to blame? – when prevention would have been so easy.

Sibusiso Mamba’s short play Taxi also had its orgin as a radio drama and was first broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Renowned South African actor, Sello Maake ka Ncube, played the role of Mzee in the orginal broadcast portraying a taxi driver who drifts the highways and byways of Joahnnesburg as he reflects on his life. His dreams and aspirations of getting himself out of debt and setting up his own business, is a reminder of the harsh economic reality that faces the majority of working-class South Africans today.

Beverly Naidoo is better known as a novelist and her work covers a wide range of themes relevant to the transformational processes we have experienced as South Africans over the past decade. Her play The Playground (based on a short story Out Of Bounds) tells the story of Rosa, a young girl, who is sent by her mother to be the first black child in an all-white school where many parents remained hostile to Nelson Mandela’s new integration laws. As Rosa’s world collides with that of Hennie (the white boy whom Rosa’s mother has looked after since he was a baby) both are forced to overcome their fears and show the courage to face each other. In Naidoo’s own words: “it is not the writer’s task to find solutions to ‘issues’ but to tell a story well”. With this play Naidoo succeeds in giving us a poignant and humane angle on the difficult process of integration that has become so relevant to our lives.

Ashwin Singh’s To House was a finalist in the 2003 PANSA (Performing Arts Network of SA) Festival of Reading of New Writing. Set in Durban, within the confines of a multi-cultural sectional title development, the play becomes a clever vehicle to explore the lives of a diverse group of characters, who each come to terms with their own prejudices. In the end, the cultural divide remains and we realise that a long journey toward the integration of our cultural differences lies ahead.

Rehane Abrahams is better known as a vibrant young actress. Her play, What The Water Gave Me is also a product of the Cape Town Theatre Laboratory’s Collaborations Festival and was further developed since its first performance. Fusing traditional storytelling, Indian Classical dance and Physical Theatre, she explores the roots of Java slave history in an attempt to manifest her own struggle toward identity. As theatre critic Yunus Kemp puts it: “Coloured identity is almost as mythic a concept as white superiority. The struggle by the coloured nation to establish one, is mired in the inability to fully recognise and acknowledge ancestors brought to these shores in chains by the colonial masters.”

As South Africa shakes off the chains of oppression and a new history evolves, the tradition and task of socially and politically aware writing still has a long journey ahead. New themes replace the old and old themes become relevant again in our society. The realities of social and economic development in our country have become more important than political issues. A new generation of playwrights will emerge in the next decade, and as we forge a culturally integrated society which respects the rights of different communities and individuals, theatre will once again be the mirror we hold up to ourselves and the rest of the world.

Charles J. Fourie

Charles J. Fourie staged his first play as a drama student at the age of 19 at the Windybrow Theatre and went on to receive the Henk Wybenga Bursary as most promising student in 1985. Since then, he has written over 40 works for the stage. His plays have mainly engaged contemporary South Africa over the past two decades with hard-hitting productions like Big Boys, The Parrot Woman, Vrygrond, Crimebabies, Stander and more recently his award-winning play Vrededorp. He has also ventured beyond South Africa’s borders with plays like Goddess of Song about the life and times of the American opera-singer Florence Foster Jenkins, and Demjanjuk concerning the trial of John “Ivan the Terrible” Demjanjuk. Big Boys was staged in London in 2002 and was a Time Out Critics’ Choice.

He has also been actively involved with promoting plays by young South African playwrights abroad and collaborated on ‘A Season in South Africa’ staged-readings at The Old Vic. His play The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife was presented at the John Caird ‘New Director’s initiative’. He has been awarded the Amstel South African Playwright of the Year Award twice, the SACPAC Award, and more recently in 2005 the KKNK Nagtegaal Award for Best Play.

Three of his plays have been filmed as television feature films to be broadcast in 2006 in South Africa. He is currently the producer of a multi-media poetry collection for Litnet.

Jayloshni Naidoo and Teboho ‘T-Bone’ Hlahane in To House Produced at the Catalina Theatre, Durban

Doreen Webster and Frances Simon in The Playground Produced by Polka Theatre, Wimbledon

Peter Mashigo and Errol Ndotho in A Man Called Rejoice Produced by BBC Radio 3

Rehane Abrahams in What the Water Gave Me Produced by the Mothertongue Project

Jennifer Steyne and Tshamano Sebe in Green Man Flashing Produced at The Baxter Theatre, Cape Town

THE PLAYS

Playwright’s Note:

What the Water Gave Me is about my connection with the Mothercity, Cape Town and thus intimately connected with my relationship to the Sea. Cape Town is on a peninsula surrounded by Ocean, the Atlantic on one side and the Indian on the other. The Indian Ocean is particularly meaningful for me and not just because the non-white beach was there, but because it carried stories of where we came from. I grew up different within, in a Cape Malay (Muslim) community with a mother from outside (Johannesburg, Christian). Apart from being not white or black, I was different from the other Coloured kids and different from the other Malay kids. My family was reeling from the ‘forced removals’ fracturing of their traditional extended family structures for most of my childhood. The geography I inhabited was one of fissures, fractures, cracks like my grandmother’s body, scarred with the many keloids of open-heart surgery. My grandmother, Gawa Arend, held the stories of Cape Town for me. She told me Bawa Mera, Bawa Puti, which I later discovered was an old Javanese story Bawang Mera, Bawang Puti (Onion and Garlic). She told me that her people had come from the East, non-specific, mythic Java, Indian Ocean and Ships.

I believe that theatre can actively be used for healing. With this work, I put those beliefs to the test using my experiences of ritual and what I found to be common – the creation of sacred space, the invocation of the directions/elements and the closure or release at the end. I also attempted to work directly with my ancestors (particularly my grandmother) and began practically exploring Southern African shamanic techniques during this time.

Faced with the gruesome realities of sexual violence and abuse, especially against girlchildren and the constant awareness of violence in South Africa, this seemed the most potent means at my disposal. In Africa, these practises are not ‘New Age’, they are continuous, ‘Age’-less techniques for the restoring of psyche amongst other things. They are effective.

The associations of water with healing, sexuality, fecundity, release and purification were called on to effect a process using the performer’s body as point of contact/interdimensional interface/channel. It aimed to connect outward to the audience and community and inward to cellular memory and ancestral line.

Rehane Abrahams

WHAT THE WATER GAVE ME

Written and performed by

Rehane Abrahams

Produced by The Mothertongue Project. Directed by Sara Matchett. Soundscape by Julia Raynham. It was first seen at the Cape Town Theatre Laboratory’s Collaborations Festival at the Nico Arena in November 2000. The Mothertongue Project also presented the show in April 2001 at The Sufi Temple, a geodesic dome in a garden. The play enjoyed a further run at the Baxter Sanlam Studio in Cape Town, July 2001.

CHARACTERS

AIR – Storyteller

FIRE – Taxi Time-Traveller

EARTH – Hip-Hop-Head from Heideveld

WATER – Little Girl

Note:

We have not included specific stage directions, as we feel it should be left to the discretion of the director and performer to invent/create their own physical narrative that runs parallel to the spoken text. We have also left the transitions from character to character up to the discretion of the performer and director.

Use is made of Indian Classical dance, Physical Theatre and Storytelling as the action moves in all directions simultaneously interwoven. This is theatre with emphasis on transformation and the corporal. It is speaking the body/the body speaking.

The Set

The set is comprised of four ‘stations’ situated in a circle. Each ‘station’ is associated with an element and direction thus representing a medicine wheel. There are four characters and each one is connected to a ‘station’.

AIR – (East) is represented by a yellow circle (approx 1 meter in diameter)

WATER – (West) by a blue circle with an empty enamel bowl

EARTH – (North) by a white circle

FIRE – (South) by a red circle

The performer enters as the audience enters the space. She is singing a Yoruba Chant in honour of the Goddess Oshun and is dragging a cloth bundle filled with various props. She carries a long stick, similar to that carried by Indian Sages. As she sings, she circles the ‘medicine wheel’ in a clockwise direction. As she gets to the water ‘station’, she takes out a plastic Coca Cola bottle filled with water and pours the water into the enamel bowl. She also places a toy doll (without any clothing) at this ‘station’. At the next ‘station’ she empties a brown paper bag filled with earth onto the white circle and places a black woollen hat down; then she takes out a large candle and lights it at the Fire ‘station’ and places approx 30 unlit small birthday candles onto the red circle and a ball; finally she places a small tape recorder/dictaphone and lights an incense stick at the yellow circle. She places her stick down here and takes the cloth that was used to carry the props and winds it round her head into a turban. Thus transforming into the first character i.e. The Storyteller. At some points the props are interchanged between characters, thus creating a sense that the characters embody aspects of one another. Again this is left to the discretion of the director and performer.

Once there was and once there wasn’t. Long ago and yesterday. Round the corner far away. In a land over the sea where the sun rises, lived three sisters. And their names were Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki. The people and animals were their friends, so they went about freely all around the place that was their home. Their father was a fisherman and he was clever and strong. Their mother was beautiful and kind and she tended the garden, she planted and harvested and filled the air with the scent of flowers. Where they lived was lush and green, so they never lacked for places to play and they dearly loved to play. Sometimes they helped with chores, but mostly they played. Their favourite spot was down on the beach by the rock pools and little ponds. And they would sing, ‘Daar onder by die dam, daar woon a Slamse man, Khadija bring die Kerrie Kos, die kinders se monde brand’. When the sun grew watery and began to set in the West, their mother would call, ‘Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki. Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki’. Aah. By the third time they were always there.

Bowa Mera the eldest, was the prettiest of the three. Mera’s face shone like a full moon on a clear summer night. Her hair was a waterfall of starfilled darkness and her smiles were cool jasmine scented breezes. Every creature stared when Mera walked by. Even the flowers blushed. As a consequence, Mera was slightly vain. She annoyed her sisters for she would leave off in the middle of an exciting game and gaze admiringly at her own reflection. Bowa Puti, the middle one, was the cleverest of the three. She was sharp and quick and knew a great many things. Already she could speak all the languages in the area, including insect and a bit of bird. She knew all the plants and trees by their formal names and could calculate the grains of sand in a bucket. At least that’s what she said. She said a great many things. Mostly starting with: ‘Did you know … ?’ And her sisters found this a little annoying. Taki Taki was the baby and something else altogether. She liked what she did because she did what she liked always. And no one dared stop her. So because she was the baby and so cute, her sisters let her have her way.

One day the sisters were playing by the rock pools. Mera was combing her beautiful hair and singing softly to her beautiful reflection in the water. Puti was observing the patterns of rock erosion, loudly. And Taki Taki was doing her own thing. So engaged were they in their separate games that no one noticed the strange man till he was right beside them. ‘Ooh,’ said Mera, ‘You startled me.’ The man flashed a dazzling smile, which Mera returned and he returned and so on until boof, Taki Taki’s mud-cake hit him square in the jaw. ‘That’s rude’, said Mera. ‘So cute,’ smiled the man. ‘Naughty Taki Taki. Say you’re sorry,’ said Puti.

Just at that moment: ‘Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki!’ But Taki Taki was already halfway up the beach running for home.

I came back to this place in a pirate ship. It docked. They threw me overboard, thought I was dead. The pirates didn’t rape me, but they wouldn’t give me any rum. I tried to run away from here, from this town, but I was kidnapped. They brought me back. I stole a cutlass. I keep it well hid. I’m going to find out what it is that keeps me here, then I’m going to cut it out, then I’m going to eat it. I’m looking for a hole. A hole in my flesh. So I can spy on my blood. See where its been. Where its coming from. Sail in its currents.

Last night I met a man that told me about the walls. He’s seen them too. Of course I didn’t let on that I knew. Shall I tell you? There are walls invisible to the naked eye that rise up in all directions in concentric circles around the city. In the twilight when you’re not looking right you catch glimmers, glimpses and the more you spy on them in this way, the more solid they become. I’m looking for a hole. Where was it? I want to get to the centre through the walls. In the centre there is a giant centipede. He eats greed. The man said.

You can’t let on you know this. They’ll try to destroy you. Got to be very hush hush. Undercover. (she hails a taxi)

Taxi. From City to Langa. From City to Sun. My friend who knew, she got found out. They knew she knew – was forced to suicide. I tried to find her. She was flying through the flaming hearts of suns. I couldn’t follow. I use public transport.

On the N2 they spot me. The foetuses in the sewerage plant make me drop my guard. Abortions are very loud. Just here driver. I switch taxis to throw them off the scent. Mitchells Plein. Soon the sun will set. Voortrekker Road. The athaan from a mosque. Maghrib. Now the spirits come. Be very careful at crossing times. Dusk and dawn. Don’t trip. Don’t stumble. Spine Road. Robots. Thank you driver.

There’s a field across the road. No grass. Just sand in a square. I must be there. Six women in hijab. Black tops, black cloaks, black scarves, pass me. They are not alive. They have no smell. They have no feet. They want me to go into the mosque. The wind rises. Six crows take off. The street is empty. The sun has gone to the western lands. Six crows follow. (sings) ‘Black crow you’re dead crow for staring at your shadow. Dead crow you’re black crow for pecking at your shadow.’ I cross the street. On the square of sand. The walls are here. They are pulsing and wet. Singing like drunk men dreaming of running away. It is dark. The walls threaten me. They say violation is my historical condition being as I am five generations out of Slavery and a woman. They are looking for a hole. A hole to put their violence in. Force entry into soft flesh with a word, blow, knife, cock, bullet. It is dark. I am not afraid. Porous, I am already full of holes. Drinking dreams I stand on the field. Nothing happens. Nobody rapes me. The sun is rising. My grandmother calls from the East. The night is over. I go … (she hails a taxi) Taxi! Cape Town.

The thing is right. (long pause) Is what it is. Is what it be like. OK, let me get to the point. When I was small, right, I couldn’t eat neapolitan ice cream just like that. Sien jy, some people, they eat one colour at a time. Some people, they take like a bite of strawberry and peppermint on the same spoon. I can’t. It goes against my nature. I got to mix it up. Till it’s one colour, many flavours. And that’s the difference, verstaan jy? Cos why? Neapolitan separated, chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, daai’s coloured. Mixed up, its caramel. Cos you see, if you mix all the colours in the paint tin, you’ll get brown. Caramel. What is caramel, you ask. It’s the new flavour. Its mutation, aberration. It’s the genetic confrontation of disparate information. It’s the clash of warring civilisations on a genetic level. There’s revolution and the colony dancing a symbiotic samba in its every cell resulting in a fierce cultural combustibility, of plat gesê, kloraheid.

With much respect to public enemy but on a point of correction, my brother, black man, white woman, brown baby, white man, black woman, still a brown baby, if I may be so bold as to paraphrase the prophet Chuck D – it’s the fear of a caramel planet. Fear of a caramel planet and that is why the white man, his only option is to go into space. It’s the tummy full of yummy. Fear of a caramel planet on a global scale. I mean, statistics are showing that California is already fifty percent caramelised and Europe, the white man’s homeland is on its way. And how do you make caramel? You heat sugar. The heat is on, my brothers and sisters, the heat is on. So whitie’s trying to escape the kitchen. Escape the contradiction on a man-made mad Mars mission in crafts of dire purpose. In a mechanised electrosised phallus, ek se, which rapes the purity of space. I mean, that’s my body. That’s my night sky, my Egyptian Goddess mother. Like this is Gaia, Earth, my Mother. NASA, stop raping my Mother. And the problem is, you can’t get there from here. NASA won’t take you there. Voyager won’t take you there. You won’t even get there on the Starship Enterprise. When you gonna realise you have to spiritualise, open up your third eyes, caramelise?

‘Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti … Aah here you are,’ said the mother. ‘We made a new friend today,’ said Mera. ‘He’s very clever,’ said Puti. ‘Monster,’ said Taki Taki. ‘Oh Taki Taki,’ they all said, ‘you’re so cute’. The next day the girls were playing at the rock pools when just as suddenly as the day before, the strange man appeared. This time Taki Taki didn’t throw a mudcake. She went off and played by herself. Mera and Puti were having such a wonderful time with their new friend that when their mother called, ‘Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki!’ they were reluctant to leave. But Taki Taki was already halfway down the beach. So they followed with their cheeks all flushed. On the third day, Taki Taki didn’t want to play at the rock pools again, but her sisters solemnly promised sweets. So off they went.

Even though the girls were waiting for him, they still did not notice the strange man until he stood right beside them.

‘Come with me,’ said the man. ‘I have something to show you. Now you all three come close together and lean over the rocks as far as you can.’ They did as they were told and there reflected in the water they saw it. A face like wormy leather, huge red eyes rolling in hollow sockets. Sharp pointy teeth and a long black tongue. A hideous monster face. They opened their mouths to scream, but before any sound could pass their lips, quick as a flash the monster pushed them into the pool. Bowa Mera he turned into a beautiful red fish, Bowa Puti into a fascinating white one and Taki Taki into a little blue fish with bulgy eyes. ‘Now you’re all mine,’ the monster growled. ‘Bowa Mera, Bowa Puti, Taki Taki!’ called the mother, but no one came. ‘Oh dear,’ said red fish Mera. ‘Oh dear,’ said white fish Puti. ‘Told you,’ said blue fish Taki. ‘Well,’ replied Mera, ‘soon a handsome prince will come and rescue us.’ So she leapt about wiggling her fancy tail and flashing her shimmering scale so the handsome princes would be sure not to miss when they passed by. ‘Mmm … ’ thought Puti, ‘there must be a logical explanation for all of this.’ And she swum about in circles looking for a simple scientific solution. Taki Taki ate insects. ‘Humpfk, humpfk, humpfk.’

By the time the moon rose, Mera was exhausted. Puti was confused and Taki Taki was fast asleep.

Miss Johnson had a baby

The baby’s name was Tim

She put him in the water to see if he could swim

He drank up all the water

He ate up all the soap

And now Miss Johnson’s baby has got bubbles in his throat.

Miss Johnson called the doctor

The doctor called the nurse

The nurse called the lady with the yellow mini-skirt

I do not like the doctor

I do not like the nurse

I only like the lady in the yellow mini-skirt

It was a game we played, most of the time under his mother’s bed. Sometimes with clothes sometimes with no clothes. We always fight about who goes on top. He says the boy goes on top, but he doesn’t really know what he’s doing even though it is his game. The bad thing about going on top is your hair gets stuck in the springs of the bed. There’s a potty to pee in; he says it’s his Dad’s. Why does he pee in a potty? Him and Carlo got a hut in the bushes, they say they got a lot of books there with pictures in. Carlo says I can see the pictures if I come to the hut. But I don’t want to let him touch me, I don’t like him, he keeps him big.

His brother, he’s in high school, asked me to sit in the car with him. There’s a lot of cars in their yard; they are mechanics. He said he would tell me a story. He has pictures with men and women with no clothes on. There was one with a man and a woman in a train. The man was licking the lady there. He wanted to do that. So he took off my panty, but no one was supposed to see. Then he went to lick me but he said it looked funny so I put my panty on and I went home. I don’t like playing that game with him. I like it with Sharief better. At least he’s my same age. Not like the teacher, Mr Walters. Sharief has a lot of books with pictures in. Mostly it’s ladies with no clothes on and licking their titties and touching themselves there. Sometimes there are men with the ladies. They were bodies that just played together like we do. And I just have to act like I know what’s going on anyway and ignore the dead feeling. Besides, its normal. Everybody does it. Everything is as it’s supposed to be. Nothing is wrong – just you’re not allowed to tell.

The thing is, right, it’s like everybody wants to be a dog these days. Like the mongrels. They all want to go bow wow wow yippee yo yippee yay to the funk like bow wow wow. Is so. Without understanding the reasons. Like Snoop doggy doggy is a negative role model for the youth. Because why, he is uncouth. Did you see his hair at the Grammies? It was relaxed and put in rollers, so it made curls, like Christmas locks. But hair, it’s not about hair. Like some people only think your hair looks nice if it’s controlled. That dog catcher song and the mongrels. See, my friend, he’s Ali from Mali, he rides taxi. His mense. Like back in the day they were visited by a being in a flaming craft and his name was Nomo and he looked like a fish. They draw him like that in the caves. And they say he had gills. This is real nè, and he taught them like, this ou Nomo, about the star system that had a direct link with Earth. This evolved mense that were in constant connection with us. Man, they were making an effort to reach out and touch. And this place was where Nomo was from. I know it’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at. But like this place was the dog star, Sirius, my broer. And anyway, he gave Ali the Mali’s mense information about the constellation and taught them this dance to keep Earth tuned into the right channel so we can keep receiving the same signal. And then the white explorers told Ali’s mense, ‘No, you are wrong. There’s not two suns in that constellation, only one. We saw it on the telescope.’ But the mense were like, that fish ou, Nomo, came here and made us wys. So gwaan! And they kept dancing and then when the explorers telescope was more powerful, years later, he checked like, ja is so. The Ali’s mense were right. And that tribe is called the dogon. So, our people always had the information already. Like before technology. So what I’m saying is, like technology is backwards. You don’t need a cellphone to make a connection. It’s like making us lazy to use our minds. And laziness is the work of the devil. Like the devil spelt backwards is lived, right? And dogon spelt backwards is like no god, right? So what does that mean? So is the devil bad?

This time it’s different. Men and women on their way to work dragging their sleep behind them. Nothing is true. Everything is permitted. ‘Stop crying or I’ll call Michael Jackson to get you.’ The child stops. His eyes wide. He has a nightmare of a moon-walking ghoul attached to his left shoulder. The roof is full of them this time of morning. Soon they will melt in the combined smells of piss and frying meat that dominate this place. Taxi Rank. On the parade. ‘Pantaloons, the devil wears pantaloons.’ He tells anyone who will listen. No one understands. I do. It is a code, a formula for initiation into a mystery of this city. I have looked for the devil since I was a child. Starting in the places my grandmother told me. The mirror at night. At sunset she said. Under the kitchen table. Under the bed. In the drains of the Bo Kaap. Licking dirty feet while the child sleeps. Sleeping in the sun after Sunday lunch. I have looked for the devil in the hope of not finding him.

Good. People with places to go. Follow them. Inconspicuous. Change direction. Keep it random. Now follow that high heel. Now that one. Now a blue shirt. Black sports pants. White jack purcells. ‘Pantaloons. The devil wears…’ back to the Parade. Try again. Blue skirt for half a block. White takkies. Dreadlocks. Handbag. And back to the Parade. Following fashion is getting me nowhere. Deep breath. Launch carefully. Tweed skirt. Yellow blouse. Briefcase. Overall. Spandex. Tie dye. Kick flare. Green-market Square. (she sniffs) Ozone. The smell of time travel. There’s the skipper. He thinks I’m dead. (she ducks) They are here. Recruiting probably. Strollers with special skills. Kidnap them like they did me. And if this is the portal for today, they’ll probably go back too, for more recruits or supplies. That skipper has a fetish for a dark rum that became unavailable after 1887. He has to have it. The smell’s getting worse. He’s a creep and I hate him. Can’t breathe. The cops all have deals with him. (she falls) Masonry is raining down on the Square. (she becomes a radio) In Istanbul today … (radio sounds) the rebel leaders are refusing … (radio sounds) a missile mistakenly fired … (radio sounds) the bodies of the hostages … (radio sounds) killing twenty-three and wounding twelve others … (radio sounds)

It’s happening. They’ve spotted me. (she runs) The walls are singing. They’re crumbling. (she dives through one) Everything’s crumbling. (she looks down) Aaaahhh! Falling … I’m falling. One day, like Alice, I fell down a very large hole, and to my surprise discovered it was my own. Down down down. Will this fall ever end? (she falls to the ground) Sis. it’s wet. Doesn’t smell like a drain. Smells musky. Like insides. It’s warm too. Heat coming from there. A tunnel. Another. More tunnels. It’s too quiet. Got to move. Choose which one to use. Keep left. Underground. Under-ground. What’s that sound? A hum? Like a generator. Coming from down there. The water’s getting warmer. The tunnel opens up. A huge room with no floor. The hum’s coming from down there. Louder and louder. The scent. The centre. The centipede. Flaming. Where’s my cutlass? Hid it too well. It’s massive. Segmented. Transparent. Made of heat. It eats people and purifies them in its digestive juices. I’m not afraid. I want … I want it to … Here Centipede … Eat me.

I’m thinking … I don’t think I’m going to play with them anymore. Then Celeste comes and asks me to go with them to the hut cos Carlo’s got new books. We went. The others were already there. Carlo’s smoking a cigarette. ‘I hear you want to tell your granny. Don’t be such a doos. So, you want to be in the gang or what? Cos you can always go play marbles in your granny’s yard…’

We were quiet. He turns the pages. It’s a children one again. The children’s eyes are scratched out with black felt tip. Sharief is there too. It’s Ramadan and we are supposed to be fasting and being holy. I feel like Allah can see us but I just act like it’s nothing but the feeling doesn’t go away. Sharief doesn’t like children, he says they not sexy. He likes big ladies with big titties. In one of the big pictures, there’s a girl our own age, with make-up on and long black socks. Why she got socks on? Carlo says it’s panty hose but there’s no panty on. Her legs are open. It’s a butterfly says Carlo. That’s what you call it when it’s open like that. It’s the only photo that doesn’t have that black felt tip on the eyes. So it’s different. It’s someone. Celeste says maybe they scratch out the eyes so you won’t recognise the child. We went closer to look into the girl’s eyes. She wasn’t crying, but it looks like she wants to. Sharief says that’s how you look when you are sexy. In the next photo, there’s a man with the girl. He’s got a long white beard like Father Christmas, but he’s wearing a sailor cap pulled low over his face so you can’t see his eyes or his face just his mouth and his beard. His hands have white hair on them. And his fingers are fat. And he’s got a fat tummy with hair on, some of it white. You can see his penis it’s very big with the hair like tummy and he’s pushing it into in-between the girl’s legs. She’s wearing clothes now, a dress that’s too babyish for her age. It’s a Sunday dress with frills and the man’s lifting it right up. She looked squashed and she’s crying in this picture but her eyes are scratched out now. The man’s got her arm like this. There’s marks on her arm, red. ‘Where’s her mommy? Where’s her friends?’

‘What? Are you scared or what? Don’t be such a doos. There’s nothing to be scared of.’

It’s just weird. In the other pictures with grown-ups it’s different. What are these photos? Are they for us? Are they for adults? Celeste says, ‘What do the grown-ups have to do with it? Children and adults can’t mix, can they?’ (she gets up) ‘My granny’s calling me. I’m going home.’ The boys all laugh.