Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

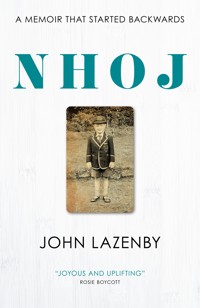

As a journalist and author, John Lazenby has spent more than forty years chronicling the tales of others. But for much of his life he closely guarded his own compelling story – a long and challenging struggle with childhood dyslexia, unable to read or write at a time when neurodiversity was rarely considered or recognised. Sent away to boarding school at the age of seven, John's future pivoted on the life-changing intervention of a teacher who finally understood the boy whom no one else could teach. In this warm and poignant memoir, John traces his misadventures through the unforgiving education system of the 1960s, when illiteracy was viewed as a character defect that could be rectified by stern discipline and regular beatings, and takes us on an evocative visit to the not-so-distant past, introducing the kind and eccentric family who never gave up on him – and the array of teachers who did. We follow the intrepid progress of a boy who could write only one word – his name, spelled backwards – to a man who finally found his true calling after a series of setbacks and false starts, only to make the late discovery that he had travelled through life unaware of a second neurodiversity, hiding in plain sight. Heart-warming, hilarious, raw and shocking, NHOJ is a tribute to overcoming challenges, ignoring barriers and holding on to hope in a world that initially seems to have no place for you.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

iv

v

To Sharon and Jean ‘If wishes were horses…’

vi

Contents

PART I

Chapter One

A juvenile gunpowder plot

In the summer of 1961, just a few months after my seventh birthday, I almost killed my grandmother.

It was an accident, of course. I certainly never harboured any murderous intentions towards her. But there were no mitigating factors in this case and no excuses. I committed an act of such reckless stupidity that I, and only I, know how close I came – a couple of millimetres, a hair’s breadth – to doing the unthinkable.

As far as my family was aware, the firework I smuggled off the top shelf of the larder that Sunday, while my grandmother slept soundly in a garden chair, soared as high as any twelve-inch skyrocket could soar. It tattooed the sky with sparks and climbed effortlessly on a triumphant, coruscating arc into the cornfield next door. That unexpected show was alarming enough in itself. But what no one knew was that for the first fateful, warp-speed seconds of its flight, the skyrocket had hurtled unerringly towards my grandmother’s head.

Obviously, that wasn’t part of the plan – not that I paid much attention to planning. My actions were mostly random, done on an impulse or an instinct, for no other reasons than they were fun 4and exciting. On this occasion, I wanted to cause a bit of a stir – a sensation – to fire up a Sunday so stupefyingly slow it had almost ceased to exist. Starved of movement and momentum, the twin elements that drove my life, I was physically incapable of sitting still for longer than a few minutes at a time. The urge to do something, to make something happen, was an irresistible force beyond my control. Unfortunately, there was also a part of me that delighted in seeking out trouble and with little concern for the consequences.

So, I thought it would be fun to launch the skyrocket, wait for the loud, crackling explosion at the top of its arc, like a ripple of applause falling slowly to earth, and then watch the expressions of horror on my parents’ faces. A juvenile gunpowder plot, in other words. Except that it turned into my horror instead.

The skyrocket had been left over from Bonfire Night – the last firework standing – and placed in cold storage on the top shelf with its stick peeping over the edge, tantalisingly out of reach yet tantalisingly attainable. If I hadn’t known better, I almost would have believed that my parents were trying to encourage me. It was impossible to miss it, and whenever I went into the larder, I automatically glanced up to see if it was still there. I knew the stick would eventually pull me in; it was always pointing at me for one thing. It was only a question of time.

The irony of my impeccably bad timing was that my father had just persuaded my grandmother to give up driving in the hope of preserving her health and safety – and that of the residents of the greater Sussex area. She was a strong-minded woman and it was no small victory, achieved after months of battling. If she wasn’t passing cars on blind bends, she was taking her eyes off the road to look at something or wave to someone she thought she recognised. Usually, her red Talbot Sunbeam was travelling too fast for that to 5be even a possibility. It was a minor miracle she hadn’t killed herself or anyone else. Her final act behind the wheel was to cause an embarrassing incident in the picturesque village of Ditchling beneath the South Downs – although, typically, she always claimed it wasn’t her fault. She removed the paint off a row of stationary vehicles in the tiny high street, leaving a jagged strip along the side of each one, so similar that it looked as if they had all been struck by an identical streak of lightning. The cacophonous scream of metal on metal brought people hurrying out of shops and doorways to see who or what had ruined Ditchling’s sleepy idyll.

‘It’s for your own good, Mother,’ my father told her when he confiscated her keys a few days later. Her racing days were over.

My troubles, meanwhile, were only just beginning.

The removal of the rocket from the larder that Sunday could not have gone more smoothly, though. Using an upturned crate to stand on, I had no difficulty lifting it off the top shelf, reaching up and slowly lowering it down, not daring to take my eyes off it for a second. It reeled me in with its dark-red cone and streamlined cardboard body, covered in red paper peppered with white stars. It was solid to the touch but lighter than I’d expected, the gunpowder so tightly packed it felt as if the slightest jiggle or vibration might cause it to ignite in my hands. I had already selected an empty jar and hidden a box of matches in my pocket. Now all I had to do was sneak outside without being detected.

I checked the coast was clear. My mother and my aunt were in the kitchen, newspapers spread out on the table, their voices competing with the sound of FamilyFavouriteson the radio. The Sunday roast was already cooking away, flooding the house with its enticing aroma. My father was on the other side of the garden halfway up a ladder, clipping the front hedge. My grandmother was asleep under 6a straw hat in the back garden and my sister was in her room. The door stood open and I slipped through it.

Safely outside, I placed the rocket in the jar on a small patch of lawn to the right of the door, out of view. In front of me was a low, scrubby hedge with an opening carved out of the middle and a brick path winding through it into the back garden, where I could see my grandmother asleep in a deckchair. She had her back to me, a cardigan draped around her shoulders, her chin resting on her chest, her grey hair escaping from under a straw hat borrowed from my mother. I took care to aim the tip of the cone well away from her and pulled out the box of matches. At first it occurred to me that the sides of the jar were too low for the rocket, which refused to stand up straight; it insisted on tilting to one side and I had to keep repositioning it so the cone was repointed at the sky. But I couldn’t go back inside and find another launch pad – that would be too risky. I told myself the jar would just have to do.

I took one last quick look around: no clouds, no breeze, the trees motionless beneath a bright sun and a vast, taut blue sky. Perfect rocket weather. I struck the match, lit the touch paper and, as I had seen my father do, immediately took two or three urgent steps back, waiting for the fizzle and hiss before ignition. And that was when fate tilted in the wrong direction.

Seconds later, there was a loud whistling noise like escaping steam and the rocket lifted off with a jolt, knocking over the jar in the same movement. The cone had slipped down again before take-off, and for one moment I thought it would fly into the hedge and no further, to be left sputtering and trapped, mangled among its thick stems. The rocket that never got off the ground. Instead, it somehow blasted its way through the top of the hedge and flew on, trailing sparks and paper while maintaining its low trajectory. 7But there was something else, something far more horrible to contemplate than any collision with a hedge: the rocket, having been buffeted off course, was now arrowing straight for the back of my grandmother’s straw hat.

I watched as if hypnotised, unable to do anything in those excruciating seconds except clench my fists as tight as I could and pray as though my life depended on it. I had never felt the need to pray before, but then I had never done anything as stupid as this. I didn’t just pray, I pleaded, ‘Please God, please God, please…’ I pleaded so hard that I snapped the match clean in two in my fist and didn’t give the pin-sharp stab of heat in my palm a second thought. I pleaded so hard that I barely noticed the gentle breeze that came out of nowhere and ruffled my hair.

However, in that moment something miraculous happened. The cone of the rocket rose fractionally and lifted over the top of the straw hat, scarcely disturbing it as it did so, and started to climb. Not even the high-pitched keening of its whistle as it passed overhead could rouse her from her sleep.

The taste of pure relief and renewed energy that surged through my body was overpowering – the shift from terror and blind panic to joy and elation was so rapid it was dizzying, like shedding a skin and growing another in the space of seconds. I couldn’t believe my eyes or my luck. I tried in vain to follow the flight of the rocket but lost its trail somewhere in the intense blue sky and dazzling sun, as though it had burned a hole in the horizon and disappeared through it. But a loud bang somewhere above the cornfield, accompanied by the unmistakable echo of crackling applause, told me all I needed to know.

Not even my grandmother could sleep through that, and she suddenly rose unsteadily and urgently to her feet, using the wooden 8frame of the deckchair to lever herself up to see where the bang had come from, its echo still reverberating. But, having woken with a jump, the effort seemed too much for her and she instantly flopped back into the canvas sling of the chair. The impact loosened the wooden slat at the rear of the chair and, in almost slow motion, both she and it collapsed in an undignified heap on the grass.

That final clap of thunder also triggered a flurry of activity as my mother and my aunt, followed by my father, converged on me from opposite ends of the garden. In the confusion that followed, I spotted Ajax, our fox terrier, sprint a succession of increasingly demented laps of the lawn and realised I had forgotten all about his terror of fireworks in my haste. He appeared to be trying to purge the sound from his head. I, however, remained rooted to the spot, the empty jar lying on its side by my feet. I needed only to glance at my mother to register the disappointment in her eyes. I watched my father disentangle my grandmother from the deckchair, reassemble it, wedge the wooden slat into place with his foot and gently sit her back down again before running over to where we were standing. He still had the hedge clippers in his hand. My mother opened her mouth as if to say something, but it was my father who spoke first. He had a habit of starting conversations with a question: what did you do that for? Has anyone seen my shoes? Why do you think that’s funny? Or maybe it was just whenever he talked to me.

On this occasion, he demanded, ‘What have you done, John?’ There was a tone in his voice that I hadn’t heard before and it caught me off guard. I wanted to tell them: at least the rocket didn’t bury itself in the hedge, at least it flew, at least it didn’t hit my grandmother. But I realised it was pointless. They wouldn’t have known what I was talking about, so I said nothing.

I felt the broken match embedded in my palm and tasted the 9cordite that hung on the air all around me, like a bad lie. The fallout had begun.

• • •

There was that word again. SPELLED. At least, that’s how it sounded to my seven-year-old ears. When I first heard it, I thought it might have been spilled – ‘John’s been spilled’ – which was news to me because as far as I could tell, I was thoroughly intact and all in one piece. But no, I knew my mother’s voice too well: the diction was so precise, so clear, it could have cut crystal. ‘John’s been SPELLED.’ That was what she said. Definitely.

I had no clue what it meant, having heard it for the first time only moments ago, yet I had already convinced myself there was something unusual about it, something special. I even repeated it several times under my breath just to make sure. I’d always loved the sound of words from an early age, which if nothing else explained my instant fascination with SPELLED – that and the fact it had been mentioned in the same breath as my name. Usually, if I didn’t know the meaning of a word, I would try to ‘read’ it by its sound alone because that was all I had to go on and SPELLED chimed perfectly with me. Perhaps it was the obvious connotations of magic that made it seem so alive, so full of hope and promise. If that was true, then I was already bewitched by it.

And there was another thing: my mother had mentioned it three times in the past few minutes, taking extra care on each occasion to wring the last drop of importance out of it. This word would soon make itself known to me, I told myself.

I was sitting at the top of the stairs, listening to my mother and my aunt indulge in their late-evening ritual of drinks, cigarettes and 10idle chat in the kitchen. Or perhaps not so idle, in this instance. It was well past my bedtime and as usual, I found it impossible to sleep. From the top of the stairs, I could see down to the back door and the hallway, which led directly into the kitchen. The kitchen itself, though, was hidden from view. If I sidled halfway down the stairs and craned my neck through the banisters to my right, I could see into it – just – but the stairs creaked and groaned like the timbers of an old ghost ship, even under my insubstantial weight, and would have given me away long before then.

Anyway, I didn’t need to see into the kitchen to know that everything was in its place. The room bathed in light and laughter, my mother and my aunt seated at the big wooden table by the window overlooking the front garden, the ashtray filling up, the stash of bottles with their colourful labels and unpronounceable (to me) names – gin, Dubonnet, vermouth, Martini, Cinzano Bianco – arranged along the bench at the far end of the room; the concoctions and potions that made their breath hotter than a furnace. I didn’t need to see into the kitchen to recognise the music of their voices that I loved to listen to when I couldn’t sleep.

It wasn’t just that their voices were comforting and reassuring. It was more the way their words buzzed and bounced off each other; it was how they dropped their voices for dramatic effect whenever they imparted a secret piece of information or made a rude comment about an acquaintance, even though they thought no one was listening. I loved the way their conversations pinballed between topics and mingled with the warm cigarette smoke that floated upstairs. Their favourite cigarettes were Du Maurier, a Canadian brand that came in a distinctive lipstick-red cardboard box, complete with a hinged lid. They always tapped their cigarettes on the lid two or three times before lighting up. I knew their mannerisms by heart.

11Even as young as I was, I could tell they were a formidable double act and one you underestimated at your peril. Strong willed, quick witted, amusing, intelligent – not to mention tall and strikingly beautiful into the bargain – they were a match for anyone and appeared to me to be all but invincible. They had a cold and reserved side to them too when pushed, and my aunt could be embarrassingly icy to anyone she disliked; they could rumble a phoney in seconds flat and send them packing for good measure. But mainly, they were fun and carefree, endlessly so, and rarely needed an invitation to let their hair down.

One of the big hit songs of that time was Chubby Checker’s ‘Let’s Twist Again’. The dance craze had erupted almost overnight, and the record stayed in the charts for a marathon thirty-four weeks, from the deep of one winter to the start of another. Often, when it came on the kitchen radio, they would turn it up as loud as it could go and start to twist, hooked on its joyous, up-tempo beat. My younger sister, Gina, and I gleefully joined in, giving it everything we had, laughing and singing along to the words while they danced around us, competing with each other to see who could pull off the most outrageous moves. They swivelled their hips, worked their arms and swung their bodies down to the floor and up again like they were drying their backs with a towel, their cigarettes pursed in their lips. On one occasion, my father paused in the doorway and stared at us in blank disbelief before being beaten back by the loud music. He had the air of a man who had just been locked out of his own house.

‘Have you all gone mad?’ he sighed.

‘What?’ we yelled in unison, barely turning our heads in his direction.

‘Have you all gone mad?’ he repeated at the top of his voice.

12‘Oh, Richard, stop being so stuffy and come and join us,’ my mother shouted after him.

If nothing else, I was just glad to have them on my side.

And there it was again. Thatword. I heard my aunt stretch it out as far as it would go, like it was a piece of elastic, until it almost snapped back on itself. SPELLED. This time, she punctuated the sentence with ‘Oh, Donty’ and what sounded like a sigh or a long exhalation of air or perhaps a flicker of amusement. I couldn’t be sure.

That was me. I was Donty. My aunt barely used my real name, unless maybe I’d been rude to her and she wanted to show me her displeasure, in which case she’d make it sound like it was something unpleasant she needed to remove from her shoe. Otherwise, it had been Donty for as long as I could remember. Donty was part of my aunt’s restless quest to invent nicknames for us all and had soon caught on with the rest of the family, which was only fair I suppose because as a baby I’d called her Dow, being unable to pronounce her name, Daphne. It’s funny how some names stick, and others don’t, and Dow would stay with her for the rest of her life – not just within the family but with the many guests and visitors who stayed at our house over the years, my school friends among them. I even felt a glimmer of pride at the way Dow tripped off their tongues so naturally.

She had moved in with us a year earlier, invading the house with her humour and vitality, her quirkiness, her piano playing and passion for betting on the horses. From then on, our days were soundtracked by the rhythm of the racing results on the radio and the familiar roll call of place names: Towcester (pronounced toaster because, I assumed, it was where the first one had been invented), Wincanton, Uttoxeter, Redcar, Bangor-on-Dee or, closer to home, 13Plumpton. Within a matter of weeks, it felt as though she had always lived with us.

I had no idea how long I’d been sitting there at the top of the stairs when I was alerted by sudden movement in the kitchen: the high-pitched scraping of a chair on the floor, the jingle of car keys. It was my mother readying herself to collect my father from the train station. ‘Oh, heavens, look at the time,’ she said, draining her drink. My mother, Virginia, was late for most things but often seemed unduly surprised by the fact. This was how their ritual usually ended, with her struggling into her coat and dashing for the door, all in one fumbling movement. Dow called out goodnight, picked up her half-full glass and her cigarettes and wandered off to her end of the house, well accustomed to the hurried curtailment of these evenings. It was my cue to leave too and tiptoeing cautiously across the landing into my bedroom, I slipped back under the covers. I always slept with my door open, and within seconds I heard the loud, disembodied roar of laughter and muffled voices from Dow’s television.

Sometimes I would lie awake and listen to two televisions, my aunt’s and my parents’, vie for my attention from opposite ends of the house. Different channels, jarringly at odds but in magnificent stereo: gunfire, horses’ hooves, the ricochet of bullets, a sudden surge of music, audience applause, heated debate. The fragments of sound collided, splintered, merged and embedded themselves in my mind, shifting like a kaleidoscope until it was impossible to dislodge them.

On this night, though, I must have dropped off earlier than usual because the next thing I recall was being woken by my father polishing his shoes in the kitchen – a task he performed without fail, last thing before bed every night of the working week. The substitution 14of one ritual for another. The brushstrokes alternated between long monotonous strokes or short jabbing movements, depending on his mood, often lasting for minutes on end. On this occasion, the strokes appeared particularly fast and relentless, like windscreen wipers battling a torrential rain. It was as though he wanted to make his shoes disappear, to expunge them, to remove a deadweight from his shoulders, and I lay there willing him to stop.

My father was a creature of habit, who regularly mowed the lawn in a cardigan and tie, even on blazing summer days, until the sweat ran down his face and my mother had to go outside and order him to rest. He spent a lifetime struggling, and failing, to throw off the burden of his upbringing. Ultimately, his life pivoted on two deathbed promises, one he had made to his father, the other to his father-in-law. The first of those promises and the most onerous, to abandon a career in the Royal Navy and take over the running of the family business – a job for which he was almost entirely unsuited – bound him to a path of such overwhelming responsibility and expectation that he could neither step off it nor leave it behind. The only option open to him was to see that path to its conclusion before it broke him.

He belonged to an old-fashioned club, one that was dwindling in numbers even then, in which a man of his word could no more go against that word once it had been given than he could betray a gentleman’s handshake once it had been made. The casual ease with which many verbal agreements and handshakes were ripped up by so-called trusted business partners, colleagues and associates never failed to sadden him. He dreamed of freedom, of escape, but realised it was futile and remained to the end of his days a prisoner, chained to an innate sense of duty. I knew nothing of the finer points of this as a small boy, only that the repeated brushstrokes, back and forth 15while I lay above him in the darkness, were lonelier than any sound I had heard. For years afterwards, I always associated the pungent whiff of Kiwi shoe polish with sadness and regret.

When his shoes were eventually buffed and shined to perfection, he placed them on a sheet of newspaper and inserted a pair of wooden shoe trees – an act, mercifully, that took seconds rather than minutes. Patiently, I waited for him to shut the kitchen door, switch off the light and go upstairs to bed. But even this relatively simple procedure turned into a trial while he triple-checked each plug and appliance, muttering ‘off, off, off’ under his breath, moving his hands in a beckoning motion as he did so, like a conductor summoning one last supreme crescendo from the orchestra. The relief I felt when he was done and finally turned out the light was enormous.

In the silence that lingered after he had vacated the kitchen and gone to bed, my thoughts returned to the word SPELLED and I tried to replay some of the conversation I’d heard earlier that evening. But I couldn’t stop my mind from racing; it was as if the atmosphere had suddenly shifted, propelled by my father’s frantic brushstrokes to be replaced by one of nagging doubt and probing uncertainty. Any confidence I had in SPELLED evaporated faster than a dream, along with my own confidence. What if I had mistaken it for another word altogether? The meaning of it remained a mystery to me after all, as did so many things at that time in my life. I knew I couldn’t risk asking my mother or Dow what it meant either, for fear of giving myself away. Things had been strained with my mother since the episode with the rocket and I was desperate to get back into her good books. And another thing: why was I the one who’d been SPELLED, whatever it meant?

My head hummed with unanswerable questions.16

Chapter Three

It will be just like a holiday

It was a new year and I was about to discover just how unteachable I was. In many ways, ‘unteachable’ could not have been a more apt description of me at that time, seeing as I already thought of myself as an un-person. After all, my teachers at St Peter’s Court were forever pointing out how untidy I was, how unintelligent, unknowledgeable and unmanageable, along with several words I had yet to learn the meaning of: unpredictable, unobservant, uncooperative, unfathomable. To my mind, unteachable would have been no better or worse than any of the others – it was just another word, an addition to the expanding constellation of terms and expressions that were regularly used to describe me.

Fortunately, unteachable or any similar-sounding words couldn’t have been further from my mind on a chilly afternoon in early January 1962 when I set off with my parents for the mysterious seaside resort of Broadstairs in Kent. I say mysterious because my parents had announced, out of the blue and in a most roundabout way, that we were going there for a holiday. What my mother said was that ‘it will be just like a holiday going to Broadstairs’. As far as I was 30concerned, that was as good as saying we weregoing on a holiday and nothing could persuade me otherwise. I was even wearing a new outfit, carefully chosen by my mother ‘for special occasions’, as she put it: a pale grey-flannel jacket, matching shorts, a light-blue shirt and black lace-up shoes. It was still two months until my eighth birthday, and the next special occasion I could think of was my sister’s sixth birthday at the end of January… but whatever this occasion was, at least I didn’t have to wear my charcoal-grey St Peter’s Court blazer with its canary-yellow piping any more. Or my cap, for that matter.

Two days earlier, my parents had announced that I would not be returning to St Peter’s Court for the start of the next term – news I was still struggling to make sense of. Mostly, I worried that I might not see any of my friends again. In the same breath, I expected to be told the name of my new school and braced myself for the inevitable revelation but nothing was said. I experienced a rush of relief and wondered whether I would have to attend another school ever again. My parents, meanwhile, had become weirdly obsessed with Broadstairs and could talk of little else, cramming my head with more facts about the town than I knew what to do with, including mention of a hotel where I naturally assumed we’d be staying. It soon took my mind off my friends at St Peter’s Court. Despite my limited experience of hotels, I loved the hustle and bustle of them and imagined big, wooden revolving doors that made a well-oiled sound, like a deck of cards being cut and shuffled, with every spin and turn they took.

On the morning of our departure, however, my parents successfully evaded and deflected any questions I had about the holiday or the hotel. They even managed to see off my attempts to separate them in the hope of catching one or the other (especially my father) 31unawares, and my best efforts to wheedle an answer out of them or pick up on a clue fell disappointingly flat. I had to admit it did seem an odd time to be going to the seaside for a holiday – not that I was complaining, though. There was already snow in the air when we drove away from home – wispy, feathery snowflakes that billowed around in circles in the wind and melted the instant they touched the ground. Rather like my questions.

‘How long are we going to be staying in Broadstairs?’

‘I told you, it’s a surprise,’ my mother repeated for about the fifth time that day.

‘What kind of surprise?’

‘Well, it wouldn’t be a surprise if I told you that now, would it?’ she answered, barely changing the tone of her voice while she concentrated on her driving, the windscreen wipers making short work of the snowflakes.

At which point, I tried a different tack: ‘Why do I have to wear this new outfit? It’s really itchy.’

‘Because where we’re going, they like you to look smart. That’s why.’

‘Who’s they?’

‘You’ll find out for yourself soon enough.’

‘But why does it have to be a surprise, Mum?’ I asked again, more out of desperation than anything. Whereupon my father briskly changed the subject.

My annoying inquisitiveness had nothing to do with the fact that I didn’t trust my parents. Of course, I did; I trusted them implicitly. For one thing, they were always warning me about the awful repercussions that awaited me if I told too many lies, which, apart from anything else, assured me that they were nothing if not truthful. It was also clear to me that I was getting precisely nowhere with my 32incessant questioning. If this was a game of patience and persistence, then I was losing it hands down. I decided there was nothing else for it but to sit back, enjoy the ride and wait for the surprise that lay in store.

Thanks to my parents, I already knew that Broadstairs boasted a famous ice cream parlour called Morelli’s Gelato, as well as an amusement arcade, a golden crescent of sand known as Viking Bay (there was also a replica Viking longboat on the beach at a place called Pegwell Bay further along the coast), a small harbour, an even smaller pier bedecked with carvings from wrecked ships and an ancient, ghostly edifice named Bleak House, which glowered out to sea, its brick blacker than beach tar. I couldn’t deny that Broadstairs sounded an interesting place, if not a little strange, and wanted to go exploring as soon as we arrived.

And yet no sooner had we crossed the Sussex-Kent border than I started to feel a slight uneasiness, an instinct that something wasn’t quite as it should be. Perhaps it was because my parents were behaving like actors rehearsing lines for a play and they’d been doing this in my company and without let-up since the start of the Christmas holidays. Perhaps it was the furtive glances they had exchanged with Dow before we drove off. Perhaps it was nothing, perhaps it was my imagination. But as the journey progressed, the feeling continued to gnaw at me and wouldn’t go away.

Invariably on long car journeys, my parents took it in turns to share the driving duties and at the halfway point they changed over. Before setting off again, my mother brought out the scotch eggs and we had a small roadside picnic. If there was an occasion that didn’t call for scotch eggs, my mother had yet to find it. My father, for some reason, always wore his hat in the passenger seat, and he took it off once he was behind the wheel and pulled on his driving 33gloves, buttoning them at the wrist. There was no doubt in my mind who was the more capable driver of the two. My mother was always comfortable when driving, instinctive, relaxed and rarely flustered; our Vanden Plas positively purred along when she was at the wheel. To say that my father was a cautious driver would be to put it mildly – he was cautious almost to the point of parody. He drove as though he had a boot full of dynamite and the slightest jolt or bump in the road could have catastrophic consequences. Before overtaking he would compute, assess and evaluate the angles, the space, the distance, the risks, the merits, the seconds, the milliseconds, and then, when every bone in my body was screaming at him to complete the manoeuvre, he would decide against it.

It reminded me of the numerous run-ins he had with my grandmother over her driving. On one occasion during Sunday lunch, my grandmother announced that she had managed to complete the 24-mile journey from Eastbourne to Brighton in only twenty minutes, despite having been advised by my father to allow for a time of at least forty-five minutes. The image of her driving in a pair of racing goggles came into my head. ‘Twenty minutes,’ she repeated in case some of us had missed it the first time around, while shooting a withering glance in his direction.

‘It’s nothing to be proud of, Mother,’ my father remarked quietly.

‘It’s Eastbourne to Brighton,’ she exclaimed, the exasperation in her voice at full throttle. ‘Not London to Brighton, for goodness’ sake.’

He patiently explained that he had factored in the additional time to account for any potential traffic delays, breakdowns or red lights on what, after all, was a busy coast road. ‘What’s the point of asking for my advice, Mother, if all you do is ignore it?’

She looked at him incredulously. ‘What red lights?’

34My father didn’t reply – instead he wore the expression of a man who’d just discovered he had a flat tyre. He would, however, go on to have the last word a few weeks later as it turned out, following my grandmother’s debacle in Ditchling high street.

My attention was suddenly diverted by my father switching on the car radio, and my heart sank instantly. It was the worst programme in the world, not to mention the most depressing: SingSomethingSimple