Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Valley Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

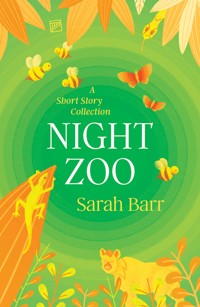

Longing for excitement in a heatwave, Liza inadvertently stumbles across the complexity of being a child in a grown-up world. Brendan is haunted by the ghosts of the past in the present, and Franny contemplates the meaning of home in a world made uncertain by global warming. With its dark twists and intense themes, Night Zoo subverts the reader's expectations at every turn. Throughout, Sarah Barr weaves an intricate, cyclical thread of regret and hope, offering captivating glimpses into the lives of her distinctive cast of characters. A compelling collection, it forms a powerful portrait of life, painting the extraordinary in the everyday. An expert blend of feminism and motherhood – set against a backdrop of climate change and with a breadth of settings explored – these stunning stories celebrate the variety and vitality that encompass the human experience.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

—————

Night Zoo

—————

Sarah Barr

Lendal Press

Heatwave

Hollyhocks and lupins show crisp brown pods, ready to pop. The paint on the white five-bar gate is blistered and smells of paraffin. The yellow lawn scorches her bare toes when she tries to run across so she comes straight back in.

‘This heatwave is dangerous,’ Dad says. ‘Don’t play outside.’

‘Lie on the couch,’ Ma says. ‘Lie quietly, Liza,’ she gasps, wiping her forehead with the back of her hand, then drawing the shiny green curtains across the window, making a clattering noise. The flies have stopped buzzing and crawl slowly across the deep sill or lie with little feet pointing up. Ma stretches out on the mat by the window as if she’s got chickenpox or some other disease. Cholera, like the grown-ups in The Secret Garden, which would be terrible. Liza’s kid brother, Robert, lolls under the dining room table, unable to push his red metal car anywhere. Baby Clemmy is in her pram in the porch and very quiet today. She’s a good baby, Ma says.

Nobody can cook lunch, so a little later Ma creeps round with bowls of mashed bananas which they can barely be bothered to spoon into their mouths. They want orange juice, cold, cold, sour orange juice, but they drank it all yesterday and the shop is shut as it’s Sunday, not that it matters because nobody could walk up the hill to the village. Clemmy feeds herself her bottle of milk as she lies back in the shade of the porch.

Hours pass and, boring as it is, Liza can’t summon up any enthusiasm to move.

The phone rings, its warble cutting through the sultry afternoon. In the distance, she hears Ma talking, saying things like, ‘Isn’t it hot and why not leave it till next Sunday…welcome for tea then…we haven’t got much to eat today…it’s the weather…we could be in the tropics.’ There’s more muttering as Liza drowses and wishes for ice-cream and delicious freezing strawberries, which she doesn’t get.

‘Can you believe it?’ Ma shrieks, returning to the dining room. ‘Some folk can’t take a hint.’

Dad lifts his head up off the table, which has paper and envelopes heaped on it, but he hasn’t been doing anything at all. Liza has been watching him do nothing. ‘What?’ he says.

‘I’m beginning to wish we’d never had that phone installed,’ Ma says. ‘It makes it all too easy.’

‘It was already here when we came, Martha,’ Dad says. Liza can’t be bothered to add that the phone is useful for calling the doctor, like when Dad had appendicitis. ‘Who was it?’ Dad asks.

‘Who do you think?’ Ma says. ‘Cynthia.’

‘Oh,’ he says. ‘It’ll be Jack and his usual and I don’t think I’ve got a bean.’

‘Shush,’ Ma says, looking at Liza. ‘Do you have to? I mean it’s not as if we’re—’

Dad shrugs, gets up slowly, pushing his chair back. ‘I feel sorry for them. In that awful, decrepit house.’ He plods upstairs and the ceiling above Liza creaks and thuds as he walks around, searching and singing, ‘Ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog,’ over and over. She’s not sure exactly what he’s searching for. If it’s that half packet of Rolos, he’ll be disappointed because she’s eaten them and even if she hadn’t they’d have melted to a pool of chocolaty toffee by now. She remembers the argument, Dad saying there were twelve Rolos in the pack and Ma that there were eleven. All because she, Liza, had secretly nicked one.

But she also suspects he’s looking for something else. She’s watched her father on past Sundays, talking to Jack out in the vegetable garden, encouraging him to grow spinach – ‘So delicious and easy to grow from seed’ – or carrots because the soil is sandy. Jack nods and smiles, then Liza sees her dad hand him something – it could be a packet of seeds. Before Jack emigrated, he and Dad worked as engineers at the same place. Now, Dad’s friend is back in this country, pauper-poor. He, Cynthia and beautiful Susan live in a very old house with a lav that has a trap-door in it to keep out rats, and a green slimy bath.

‘Righty-ho,’ Dad says, when he returns to the room after a while, puffing a little, and still humming that song. He slips his feet into sandals. ‘What time will they arrive?’ Her Dad is kind, Liza thinks, although nobody ever says it. She already believes that kindness is one of the most important things, maybe the most important thing, in life.

‘About now,’ Ma says. ‘But she mentioned they might run out of petrol.’

‘Put the kettle on,’ Dad says, ‘Any Swiss roll?’

‘Stale,’ Ma says. ‘We could use the last of the christening cake. Liza, you can’t lie there all day, you’ll never sleep tonight. Go fetch a bottle of milk from the outhouse, please.’

When Liza gets outside, the sun wallops her in the face. Never look at the sun, they told her when it was the eclipse, so she doesn’t, she squints between her fingers. The garden path shimmers in the fierce light, like magic. She glances over to the gate and is surprised to see Susan’s family’s navy-blue car with its silver front bumper and cracked yellow windows already parked in the lane.

She creeps through the bushes close to the hot, sticky fence, her arms getting scratched by the holly and spider webs sticking to her face. She manages to get near without being seen. The car is shaking and rattling and someone’s crying. Is it Susan? Or is it her mummy? If so, what has she done wrong? Susan’s dad shouts angrily, she can’t hear what but it’s something like, ‘Why? Why the devil can’t you be more careful?’

As she crouches in the centre of the rhody bush, Liza hears the car door open and then sees Susan slide out quietly. Susan tiptoes through the gate and along the path, her long red hair swinging behind her in a ponytail that’s tied with a lemon bow to match her lemon frock. She isn’t crying but she looks sad. She’s taller than Liza even though she’s six months younger, but she’s no better at playing bandits or explorers, and she’s not as good at walking along the top of the high wall. Susan tried it just once, a few wobbly steps, before begging Liza to help her down. If Susan had fallen, she might have cracked her head on a stone and lain white-faced on the grass, legs twisted, like a girl in a story. But that would not have happened because Liza would have caught Susan and saved her.

Susan waits by the side of the house, looking in the front window, her fingers plucking at the rough red brick. While Susan’s back is turned, Liza sidles along the back of the bushes then jumps out shouting, ‘Hello, Susan, I can see you!’ Her friend shudders, a frightened expression on her pale, freckled face.

‘Oh! Just waiting for Mummy and Daddy to come, just—’

‘Let’s climb trees,’ Liza says, scraping sweaty hair away from her face. Susan smooths down her dress. It looks like an iced cake. Liza would love it but she’s wearing a shrunken faded smock that hasn’t looked right on her since she was four.

As they walk away from the house, Liza remembers she never took the milk to the kitchen. They’ll think she’s forgotten – they say she’s ‘impractical’. Liza has never told anyone about her memory. Sometimes she wishes she didn’t remember word for word what people say, all those sentences arranged so clearly in her head, ready to voice themselves when she’d rather forget.

Liza takes Susan’s hand and pulls her up the slope to the shady trees – apple, pear, a big oak and some silver birches. She scrambles into the low fork in the apple tree. ‘You climb up and sit here. I’ll crawl along the branch,’ she explains.

Susan shakes her head, her eyes downcast. She smooths the yellow material as if it’s the only thing that matters. ‘I can’t. You climb, I’ll wait. This dress was sent from America and it was very expensive.’

‘Take it off, then,’ Liza says, ‘you must be boiling.’ Susan giggles, her pale face going red. ‘Sometimes I climb up in my—’ Liza stops because she thinks Ma would be cross with her if she tells Susan about how she plays outside in just her knickers and liberty vest when it’s washing day.

‘In your what?’ Susan looks interested.

‘My dressing-up clothes. I showed them to you when you came for my birthday, remember,’ Liza says.

‘Can we do dressing-up now?’ Susan asks. But putting on those fox furs and Ma’s sweltering velvet cloak is absolutely the last thing Liza wants to do on this hot day.

‘Later. Let’s go and eat peas,’ Liza says. She scrambles along the rough, swaying branch, lowers herself over it, then swings from it back and forth before landing in the grass and rolling over down the slope. Even the moss and tree roots are baking in the sun.

Liza and Susan lie in the long grass at the side of the vegetable patch, a heap of peas between them. They break open the pods and thumb the line of peas into their open mouths. These peas are usually delicious, sweet and cool, but overnight their pods have wrinkled and turned yellow, the peas become floury and slightly bitter. Even so, Liza gobbles them up, and Susan’s as well. Liza is just about to run over and grab some more when she hears the men talking as they make their way to their usual spot by the vegetables.

Only yesterday, Dad told her about the ‘two-legged birds’ that had been stealing his crop so there were never enough peas for a meal. ‘Two-legged birds?’ Liza asked, thinking which birds have more than two. She tried to imagine a bird that had more. Dad laughed and she wasn’t sure if he was joking or not.

She puts her fingers to her lips and the two girls lie down flat in the long grass, trying not to giggle. Ants run along Liza’s arms. Susan lies with her eyes shut, little red heat bumps appearing on her neck and face.

Liza remembers when she was younger, looking over the gate at the mad rabbits with bulging eyes running round and round on the grass by the woods. She was standing on the middle bar of the gate with Ma’s arm around her. Dad said, ‘I need a rifle, put them out of their misery.’

Ma said, ‘Can we still eat rabbit, with that disease?’

Dad said, ‘Only if well-cooked.’

Liza imagined Dad shooting the rabbits, the banging, the squealing, the blood. The scene lodged inside her head as if he’d actually done it, which she’s pretty sure he hadn’t. Now she has a horror of rabbit stew. They try to kid her that the meat is something else – chicken or mushrooms – so she is always suspicious of anything in a sauce.

Dad and Susan’s dad amble over to the rows of wilting spinach. Liza peeps up and sees Dad is carrying a shopping bag. Liza scrunches her hair away from her ears to hear better but even so, it’s all mumbles. Dad offers Susan’s dad a cigarette and smoke curls up above their heads - she can smell it. Dad shakes his head, mutters, ‘I don’t know, Jack…is it such a good idea…’

Susan’s dad’s voice is higher and more shouty. ‘I can manage one. Just one. Two is too many. You know that! You see the fix we’re in.’

Susan is asleep, her mouth hanging open, making little snores and snuffles. Liza feels like going to sleep herself, now the sun is going down, the day not so sweltering.

‘Money won’t do it!’ Susan’s dad yelps, wiping his face with a hanky. ‘Don’t know where to go, who to ask. Do you? Can you help us?’ Dad shakes his head slowly which surprises Liza. Dad always knows who to ask if they need something. The two men walk to just a few feet from where the girls are flat out behind a ridge in the long grass.

‘You could try this,’ Dad says, taking out of the shopping bag the green striped cardboard shoe-box that once contained his leather work shoes and which, as Liza knows only too well, has been kept hidden at the back of the wardrobe ever since they moved here. ‘Martha suggested a douche…but she didn’t like to say.’

Doosh is a nice-sounding word that Liza hasn’t heard before. She will remember to write it in her notebook.

Susan’s dad takes off the box lid and peers inside. ‘We decided against using it,’ Dad says, his voice wobbling as if he’s embarrassed or very tired. ‘We just couldn’t.’ Dad couldn’t? Liza is puzzled and yearns to understand.

‘I realise that,’ Susan’s dad says, sniggering.

Inside the box is a funny brown rubber thing with a squeezy pouch attached to a tube. Liza knows this because she’s got it out of the box a few times then hidden it back in the wardrobe. It was like something Dad would use to clear the taps or drain, something that water goes through and you squirt, she thinks, but she’s never asked because she knows Ma’s and Dad’s bedroom is private and she shouldn’t be ferreting around in there.

‘I’ll take it. I’ll make her use it. Make her,’ Susan’s dad says, putting the box back in the shopping bag which Dad fills up with spinach and beetroots he yanks out of the parched earth.

‘It may not work at this stage,’ Dad says, catching hold of his friend’s arm. ‘And it’s risky, be careful.’ Susan’s dad just goes, ‘OK, OK.’

Liza imagines it must be something useful for their old-fashioned, stinky bathroom. She doesn’t tell Susan what happened while she was asleep, but later she goes over and over it in her head: the vegetable plot, the two men, what was said, until the scene fixes inside her.

That night there’s a thunderstorm, the rumbling and bellowing coming nearer, then giving tremendous cracks right above their house. Liza lies in bed watching her bedroom lit up in an instant, a huge shadow of her rocking horse against one wall, then all dark again.

Dad comes in. ‘Are you all right, sweetheart?’ He goes over to the window and shuts it. Liza runs out of bed to stand with him and look through the wet glass at the fruit trees shaking their branches in the lightning and the gate banging to and fro at the side of the house. ‘These curtains are soaking,’ Dad says, drawing them over the window. ‘Jump back in bed. I’ll check on Robert and Clemmy.’

Liza hears and watches the storm all night. In the morning, the house is still and cool. The grass outside is wet and fresh on her bare feet as she runs across to pick peas in the vegetable patch.

House of Spirits

‘You can’t go out like that, Anna. I can see everything through that Aertex shirt – put a vest on.’ My mother’s words and her disapproving stare made my cheeks flush, my chest tighten, ashamed of my eleven-year-old body.

I ran upstairs, pausing for a second in front of the long mirror on the landing. It was true. Two pink lumps had appeared on my chest. That was bad, obviously. I tore off the revealing white shirt and rummaged in the moth-bally drawer, finding an old vest which I squeezed myself into. I was fat. I pulled on a home-knitted, thick jumper that would scratch my skin and give me spots.

‘What on earth do you want to walk that dog for?’ she said, laying out biscuits on a doily-covered plate. They were crisp biscuits with hard, glossy, coffee icing and I knew the ladies’ flower-arranging class would eat the lot.

I hesitated, scuffing the edge of the green kitchen lino with my sandal, unsure whether to tell her I wanted to be a vet like Katherine (very unlikely as I wasn’t clever enough). Or, say I felt sorry for Mr Pearson, on his own as Mrs Pearson was out at her job. I said nothing.

‘Go on then, they’ll be here soon.’ She wanted me out of the way before her friends arrived. I wasn’t what a girl should be, probably not what she’d been like. ‘And don’t go into Mr Pearson’s house. Stay outside if he gives you a drink. Remember what I’ve said, now.’

I raced down our tarmacked drive, jumping high, higher, kicking my heels, pretending to be the funny, bucking Shetland pony at the riding stables. I loved animals but I wasn’t much good with them, was even a little frightened of them. I didn’t know why I’d set myself the challenge of walking an enormous Labrador which was bigger and heavier than I was. Once a day for the whole summer, that’s what I’d agreed.

The Pearsons’ house had originally been identical to ours. But theirs had peeling paint, long dry grass for lawn, a pot-holed drive and a ramshackle carport where we had a garage.

They couldn’t afford to keep it up. My parents said Mr Pearson wasted money on things he shouldn’t, especially considering he was retired.

Tawny heard me coming and bounded down the path, a massive yellow monster who had no respect. He jumped up, his smelly, dripping tongue wrapping itself around my face, hands, toes in open sandals. His claws tugged loops of wool out of my jumper.

‘Come on, you terror.’ Mr Pearson walked out onto what he called the verandah, and fastened a lead on the straining hound, waved goodbye and off we went, tearing out into the road, the lane, the dusty, summer woods.

I had a choice, be yanked wherever, or let him off the lead, watch him disappear into the scrub, then spend an hour calling, calling, before returning, usually on my own. If that happened, I’d loiter in the lane outside our houses, waiting for Tawny to turn up, looking pleased with himself and covered in cow-pats.

This afternoon, keeping him leashed, I eventually managed to pull him to heel at the edge of the woods. Although I felt drawn to the gnarled, lichen-dappled trees, clay pits, and bogs that could suck you down, it was a place I wasn’t allowed to go into on my own. One day I would, fearless like Mr Pearson in the Himalayas.

We went back up the hill. We met an Alsatian. Predictably, Tawny yelped, snarled, and charged over the road. The horrible Alsatian leapt at me, its teeth ripping a hole in my sleeve. Its owner grabbed it.

‘Keep control of your dog and stop it pestering mine!’ he bellowed.

I tied Tawny to a lamp post and went into the corner shop. The man tutted but he took the pound note and the written instructions and handed over the brown parcel, which I had to carry carefully back. I checked the time. I could return – the hour was almost up.

This was the sort of thing my mother totally disapproved of. I knew that, eventually, someone would tell her that I was being sent on errands by ‘that man’, who didn’t want to be seen going into the village stores because word would get back to his wife. But for now, we were getting away with it.

Mr Pearson was in the garden, smoking, with Chotapeg, their little terrier who was too ill to go walkies.

‘How are you, Annabella, Mirabella? Goodness, you must be boiling in that woolly. It’s the middle of summer my girl, didn’t you realise? Come in and have a glass of something.’

‘Is Katherine at home?’

She was the Pearsons’ only daughter, cool as a cucumber, and at University. ‘Smoking pot is far less harmful than smoking ordinary cigarettes or drinking to excess,’ she’d said, shocking my parents who’d invited them all round at Christmas. When the guests had gone, Mum and Dad had a big argument. It was something about – why did we have to live on this sort of a road?

‘No, Kate’s in Marrakesh. You look as if you could do with an ice-cream soda and I could manage something, too.’ We went inside. He poured a tall glass of lemonade, dolloped two delicious scoops of vanilla ice-cream into it and finished it off with a handful of raspberries, a multi-coloured straw and two wafers. ‘Now, how do you like that?’ I liked it very much.

‘What do you think of this, just come out?’ He put a record on his player and, with a shaking hand, he placed the needle. ‘We all live in a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine—’

‘I didn’t get it, now I’m enjoying it, undemanding. Lord knows what it really means. It’s Kate’s. What do you make of it?’ he asked.

‘It sounds happy,’ I said.

‘Happy. Yes. Happy. Hippy.’ He sighed and then laughed.

He took the parcel I gave him and unscrewed the bottle of vodka. After he’d poured some into a tumbler, he filled the bottle with water and pushed it right to the back of the kitchen cupboard. ‘Don’t tell Mrs Pearson. She thinks I don’t know she knows and I think… well it’s complicated.’

‘Here’s to my old friend Barney.’ He gulped the drink. ‘That’s good, Bella. Poor man, he got mauled by a tiger, up in the hills.’ Mr Pearson liked remembering about when they’d lived in India. ‘Life was hard but exciting,’ he said. ‘Then they made me give up the farm and come back here to put my feet up.’

We sat in the conservatory. He rummaged around and found a bottle of what he called malt. He poured himself a drink then wrapped the bottle in a blanket and squashed it back into the window seat. ‘Here’s to my cousin, Tony, who distinguished himself in the war, an exceptionally brave fellow. Dead.’

He kept brandy in a wellington boot and would sample that next.

‘When you get to my age, all your friends are dead.’ I felt sad and he must have noticed. ‘Correction. Not all my friends,’ he said, ‘because I’ve got you to play chess with.’

I patted the two dogs, both now docile in the sun. We set out the chess pieces on the teak board Mr Pearson’s father had made. The pinnacle of pleasure for me was simply looking at those pieces, ebony one end, pale woody colour the other, all lined up in exactly the same order each time we started a game. I loved the symmetry. I liked noticing the differences between the ornately carved kings and queens, and the tiny plain pawns, so unassuming but which, if luck was on their side, if they played their game cunningly, could become queens.

I knew the moves. We started to play our customary game. Mr Pearson almost always won, but that was OK. I didn’t expect to win. Just occasionally, his concentration lapsed and then he’d accept his downfall with good grace. ‘Mulligatawny soup, I’ve left the rook undefended!’ I looked out for signs that he was letting me win deliberately, but I didn’t see any.

This was why I put myself through the whole dog-walking torment, although I never admitted to anyone that it could upset me.

‘Here’s to you,’ he said, raising his glass as I took his castle. ‘You’re clever. And good at keeping secrets.’ I nodded, trying not to smile too broadly at these compliments. ‘You could be a detective when you grow up. Or how about a spy? The world’s your chess-board, Annabella, Mirabella. Remember that. The world’s your chessboard. Plan your moves, wait for your time. Don’t give up.’

The Gold Watch

It was nearly closing time on a cold January evening when the gentleman came into Messrs Featherstone and Cotton, clanging the door to and stamping mud off his feet.

‘Go and see to him, Jenny,’ Mr Cotton said through a mouthful of pins. He was in the storeroom, arranging hats on stands ready for the following Monday. I was sewing Petersham ribbon around a felt beret. I wasn’t a trained milliner but could adapt and prettify the hats my employer bought in.

My job was long hours for low pay but it made all the difference for me, Mam and the three little ones. To the outside world, it was a respectable job, even though all sorts came into the shop.

Unaccompanied gentleman customers rarely knew much about hats. If they did come in to choose one as a present for a lady-friend, it would usually be returned the next day. Sometimes the woman asked for the money back, which was awkward.

This man wore a homburg, a military-style overcoat and he was carrying a newspaper. He had the solid, sleek air of the wealthy.

He wanted a broad-brimmed lady’s hat – ‘frothy’ he said. He meant muslin and lace. I explained that, as it was winter, we had that style only in black. Not many women want to be swathed in black lace, unless they’ve suffered a bereavement, of course. I didn’t say that, though. It was too close to home for most people, with the war and then the grippe.

The customer smirked, picked an ostrich feather from the pewter jar and tickled my chin. He took out a gold pocket watch. ‘I’ve got an appointment the other side of town in one hour’s time. Be a good little girl and find me a hat. Fashionable but not one of those turbans.’

As I passed him with the step-ladder, he squeezed my bottom, and when I yelped, he twizzled me round close to him, pushed away the steps and kissed my mouth. His lips were soft and his tongue tasted of whisky and tobacco. His stubbly moustache was sharp and stinging against my nose. I sneezed.

‘Shush,’ he warned, pulling away suddenly and pinching my nose.

‘I’m not that sort of girl, sir,’ I said, pushing roughly at his plump, waist-coated chest. I knew to nip this sort of attention in the bud. I wanted to make something of my life.

‘Are you not?’ he whispered. ‘Then don’t tempt me with those big brown eyes.’ He watched carefully as I climbed the steps. I was all too conscious of the darned holes in my black wool stockings. I lifted down a tower of hat-boxes. ‘Chop-chop, the hat, please, missy.’

Mr Cotton was clattering around in the back, packing things away. He went to his sister’s for dinner on Saturdays and wanted to leave on time. I’d go and fetch him if there was any more nonsense from this customer. I could always ring the bell, which was close to hand.

I was shuddering inside but wouldn’t allow this to show. I kept wiping my clammy hands across my skirt, hidden by the counter, while the gentleman looked through the choices. At least he didn’t ask me to try any on.

He chose a coffee lace hat left over from autumn stock. I packed it in a cream and brown striped hat box which he strung over his arm. ‘My offices are in this part of town,’ he said as Mr Cotton came in to take the money. As I opened the door to show him out, he murmured in my ear, ‘Beautiful, soft hair.’

I noticed he’d left his newspaper behind but I didn’t feel like running after him, so I folded it and popped it in my basket to read on the bus on the way home.