9,95 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Glagoslav Publications B.V. (N)

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

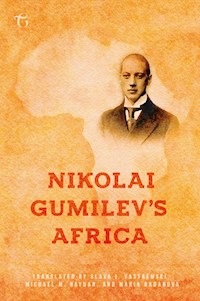

Gumilev holds a unique position in the history of Russian poetry as a result of his profound involvement with Africa. He extensively wrote both poetry and prose on the culture of the continent in general and on Ethiopia (Abyssinia, as it was called in Gumilev’s time) in particular. During his abbreviated lifetime Gumilev made four trips to Northern and Eastern Africa, the most extensive of which was a 1913 expedition to Abyssinia undertaken on assignment from the St. Petersburg Imperial Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. During that trip Gumilev collected Ethiopian folklore and ethnographic objects, which, upon his return to St. Petersburg, he deposited at the Museum. He and his assistant Nikolai Sverchkov also made more than 200 photographs that offer a unique picture of the African country in the early part of the century.

This volume collects all of Gumilev’s poetry and prose written about Africa for the first time as well as a number of the photographs that he and Nikolai Sverchkov took during their trip that give a fascinating view of that part of the world in the early twentieth century.

Translated by Slava I. Yastremski, Michael M. Naydan, and Maria Badanova.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 239

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

NIKOLAI GUMILEV’S AFRICA

Nikolai Gumilev

NIKOLAI GUMILEV’S AFRICA

Translated from the Russian by Slava I. Yastremski,

Michael M. Naydan, and Maria Badanova

Edited by Michael M. Naydan

Book cover and interior design by Max Mendor

© 2018, Slava I. Yastremski, Michael M. Naydan, and Maria Badanova

© 2018, Glagoslav Publications

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN: 9781911414650 (Ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

Introduction

Poetic Works

I. From Romantic Flowers, 1908

The Gardens of My Soul

An Incantation

A Hyena

Horror

The Lion’s Bride

The Plague

Giraffe

Rhinoceros

Lake Chad

“From the distant shores of the Nile…”

II. From A Foreign Sky, 1912

By the Fireplace

Abyssinian Songs

I. A War Song

II. Five Oxen

III. The Slaves’ Song

IV. The Women of Zanzibar

III. From The Quiver, 1915

An African Night

IV. From The Bonfire, 1918

The Azbakiya

V. The Tent, 1921

Introduction

1. The Red Sea

Egypt

The Sahara

The Suez Canal

Sudan

Abyssinia

The Galla

The Somali Peninsula

Liberia

Madagascar

Zambezi

The Damara

Equatorial Forest

Dahomey

The Niger

Untitled

VI. From The Pillar of Fire, 1921

A Leopard

VII. From uncollected works

<An Acrostic>

A Poem to the Music of Davydov

“Palm trees, three elephants, and two giraffes”

Christmas in Abyssinia

Algiers and Tunis

Abyssinian Songs

“One cannot escape death: there once was an Emperor Aba-Danya…”

“This night I saw a cat in my dream…”

“Menelik said: “I love those who saddle…”

“The attacking warrior is as strong as a pillar…”

“The greatest joy is to watch…”

“There is fire in the Negus’s rifle…”

“As people, upon seeing Liege Iyassu, tremble with fear…”

“Hoi, hoi, Aba-Mulat Haile Georgi…”

“One who kills a lion is greater than one who kills an elephant…”

“Hume and Dagome53 together own the world-stone…”

“Chavello is a beautiful place where the reed grows…”

VIII. Prose Writings

Princess Zara

The Forest Devil

The African Hunt

Upstream along the Nile

Has Menelik Died?

The African Diary

Notes

The Photographs From The Gumilev Africa Expeditions

Thank you for purchasing this book

Glagoslav Publications Catalogue

Introduction

On Gumilev’s African Poetry

Western readers perhaps know Nikolai Gumilev primarily as the husband of the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. In his time Gumilev was a recognized poet, one of the most important figures in the culture of the Silver Age in Russia, even before his marriage to Akhmatova (who incidentally was not yet an established poet when they married). He was the founder of Russian literary Acmeism, which comes from the French word acme, meaning the summit or pinnacle. Along with Symbolism and Futurism, Acmeism comprised one of the three most significant poetic movements in early twentieth-century Russia and focused on “beautiful clarity” (the poet Mikhail Kuzmin coined) and simplicity of expression instead of the profoundly complex and symbolic nature of the word in Symbolism, one of Acmeism’s immediate literary predecessors. In addition to Gumilev and Akhmatova, the major Acmeists included Osip Mandelstam, Sergei Gorodetsky, Georgy Adamovich, as well as a few others. To differentiate Gumilev from the other Acmeists, one can characterize his poetry by its vivid imagery, bright colors, and exotic locales that entered his poems from numerous travels to France, Italy, England, and, what became most important to him, Africa. The poet rightly called the source of his creativity the Muse of Distant Travels.

Gumilev’s life was as bright and fascinating as his art. In fact his biography often overshadowed his achievements as a poet. The critical moment that defined his biography was his execution in August 1921 on charges he participated in a counterrevolutionary conspiracy. In recent years those charges were proven to have been completely false and fabricated by the Soviet secret police. Gumilev was the first major artistic figure to fall victim to the Soviet regime, and his name, especially in immigrant circles, became a symbol of resistance to Soviet totalitarianism, despite the fact that political motifs occupied a very modest place in his writings.

What distinguishes Gumilev not only from other poets of his generation but indeed places him in a unique position in the history of Russian poetry is his profound involvement with Africa. He extensively wrote both poetry and prose, on the culture of the continent in general and on Ethiopia (Abyssinia, as it was called in Gumilev’s time) in particular. During Gumilev’s abbreviated lifetime he made four trips to Northern and Eastern Africa, the most extensive of which was an April-August 1913 expedition to Abyssinia undertaken on assignment from the St. Petersburg Imperial Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. During that trip Gumilev collected Ethiopian folklore and ethnographic objects, which, upon his return to St. Petersburg, he deposited at the Museum. He and his assistant Nikolai Sverchkov also made more than 200 photographs that offer a unique picture of the African country in the early part of the century.

African motifs began to appear very early in Gumilev’s poetry, even before he actually visited the continent. According to Gumilev’s own personal assessment, his first “acceptable” collection Romantic Flowers (1908) contains poems thematically centered around Lake Chad, which, at that time the poet associated with the heart of mysterious Black Africa. For the most part his treatment of Africa in the poems from this collection is affected by Gumilev’s favorite writers of that time – Jules Verne, Captain Mayne Reid, and especially Ryder Haggard. The poem “Incantation,” for example, is directly based on Haggard’s novel Cleopatra, particularly on the scene in which the priest Harmahis shows Cleopatra (who usurped his throne) the mysteries of the Egyptian gods. In this poem we also find the image of the “pillars of fire” that later will become the title of Gumilev’s last collection of poetry (published posthumously in 1921). Gumilev’s poem “Giraffe” became the cornerstone of this collection and became Gumilev’s trademark in bohemian circles of pre-war (WWI) St. Petersburg. On the whole the African imagery in Romantic Flowers is somewhat abstract and closely resembles the pictures of British Pre-Raphaelites and Russian Art Nouveau artists. In the collection Gumilev idealized Africa as an exotic Orient.

The collection A Foreign Sky marks a change in Gumilev’s treatment of the African theme in his works. The change was undoubtedly caused by the poet’s immediate experience on the so-called Dark Continent. By the time he published the collection Gumilev had made two trips to Africa – a brief one to Egypt in 1908 and a much longer one to Abyssinia in 1910. His poems after those two journeys include actual details of African nature and Gumilev’s own engagement with it. In the poem “Ezbekiya” from the 1918 collection The Quiver Gumilev reflects on his visit to the Cairo garden in 1908. At that time he was preoccupied with thoughts of suicide because of Anna Akhmatova’s rejection of his marriage proposal, which she subsequently accepted two years later. The visit to the Ezbekiya garden healed Gumilev spiritually, and all his future trips to Africa had the same beneficial effect on his state of mind and inspired him artistically.

The collection The Tent (1921) became the most significant among Gumilev’s poetic works on Africa and was published a few months before his execution. It consists entirely of poems dedicated to Africa. As his wife Anna Akhmatova noted in her memoirs, The Tent is a book of geography in verse. This statement is supported by the memoirs of the Russian explorer of Africa V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko to whom Gumilev said in 1921:

“I am writing a geography in verse. It is the most poetic of all the sciences but people make some kind of herbarium out of it. I am now working on Africa, the black African tribes. I must show how they imagined the world for themselves.” The plan for a large poetic book of a “geography in verse” was discovered among Gumilev’s archival papers. It consisted of six sections: Europe, Asia, Africa, America, and Australia. The outline of the African section showed that Gumilev intended to write his poems in correspondence to an imaginary trip around Africa, starting with Egypt, then following the Western coast of the continent, and ending the journey at the Red Sea. It must be noted that the journey, with the exception of its beginning and the very end, would take place in locations where Gumilev had never been. In comparison with this plan, The Tent consists almost entirely of poems dedicated to those places in Africa that Gumilev visited several times, the central of which comprises the area of the Horn of Africa that includes Abyssinia, Galla, Somalia, the Red Sea, and adjacent to the latter, Egypt and Sudan.

Gumilev visited Abyssinia at the end of the reign of the country’s great leader Menelik II, who in 1896 defeated the Italian army at the river Adwa and won independence for Abyssinia, which was the only uncolonized African country at the end of the 19th century. It had a special appeal for Russia (which didn’t participate in the “scramble for Africa”) because of the shared with Ethiopia Eastern Orthodox religion. Gumilev’s poems include many references to the history of Ethiopia – from the legendary Axum empire to the times of the more recent military and government leaders such as Ras Mekonnen and the prophet Sheik Hussein – as well as some comments on the modern social issues of the country, such as the conflict between the indigenous population and the Europeans. In the collection The Tent, Gumilev’s African landscape becomes as real as the people who populate it. The poet includes his personal recollections of traveling through various parts of Abyssinia, and in descriptions of those parts of Africa where he was not able to go, he proceeds from concrete visual imagery: maps, pictures, and actual artifacts, as is evident in the last poem of the collection “The Niger.”

In sum in retrospect we cannot consider Gumilev to have been a “politically correct” writer in regard to his writings on Africa. His views certainly can be characterized as “Orientalist” by present-day standards. However, his African-themed poems bear the stamp of not only his genuine love and understanding of different independent African cultures but also of an actual merging with at least one of them and depicting it from within, from the point of view of a participant.

Slava I. Yastremski

Professor of Russian Bucknell University

A Note on the Translations

This edition for the first time compiles virtually all of Nikolai Gumilev’s Africa-themed works (poems, prose, and diaries) in a single volume in English translation along with a number of extant photographs from the Gumilev archive in Russia. I have stuck to Slava’s outline and design for the book, which has been a longtime labor of love for him. Many of the translations are appearing in English for the first time.1 After my co-translator Slava Yastremski succumbed to illness in November 2015, I was able to download all his materials on Gumilev from his laptop thanks to Slava’s widow Irina, who was kind enough to give me access. She also gave me the photographs from Gumilev’s African travels that Slava had obtained earlier from the Gumilev archive in Russia for publication in this volume. Given the age of the photographs and Gumilev’s death in 1921, all these works lie in the public domain. While Slava’s and my translations were approaching completion when he died, he was too weak to do a final edit the months before he passed away. Therefore I have decided to include an edit by my very talented honors college undergraduate student at Penn State Maria Badanova, who did a marvelous job in checking and editing this final manuscript and improving it. I am grateful to Laird Jones for sharing his expertise on Africa with me for this volume. I am responsible for any errors or omissions that might have slipped through. I have decided to use English equivalents of words that Gumilev uses such as “Negro” (negr) and “dwarf” (karlik) instead of versions of those words preferred in contemporary English usage to keep to the style of colonial usage extant in the poet’s time.

Michael M. Naydan

Woskob Family Professor of Ukrainian Studies and Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures The Pennsylvania State University

Poetic Works

Part I

From Romantic Flowers, 1908

The Gardens of My Soul

The gardens of my soul are always filled with patterns,

In them the winds are so fresh and blow so softly,

In them you find golden sands and black marble,

And pools that are deep and entirely translucent.

In them, just as in a dream, plants are extraordinary,

Birds glow pink like water in the morning

And—who can understand the clue to an age-old secret?—

In them, there is a maiden wearing a High Priestess’ wreath.

Her eyes are like the reflections of pure gray steel,

Her graceful brow is whiter than eastern lilies.

She has lips that have kissed no one

And that have never uttered a word to anyone.

Her cheeks are pinkish pearls of the South,

The treasure of unthinkable fantasies,

Her hands that have only caressed one another

When intertwined in the ecstasy of prayer.

By her feet, there are two black panthers

With a metallic tint to their fur,

And flying up from the rose bushes of a secret grotto

Her pink flamingoes float in the azure.

I do not look at the world of streaming lines,

My dreams are obedient to nothing but the eternal.

Let fierce sirocco winds rage in the desert,

The gardens of my soul are always filled with patterns.

An Incantation

The young magician in a purple tunic

Spoke mysterious words

Before her, the queen of lawlessness,

He squandered rubies of magic.

The aroma of the burning incense

Opened spaces that knew no limits

Where gloomy shadows were rushing,

Looking like fish, then like birds.

Invisible strings gently sobbed,

Pillars of fire floated in the air,

Proud military tribunes submissively

Lowered their eyes like slaves.

And the queen disturbed these mysteries,

Playing with the loftiness of the universe,

And her silky-smooth skin

Intoxicated him with its snowy whiteness.

Yielding to the power of her whims,

The young magician forgot everything around him,

Looking at her small breasts,

At the bracelets on her outstretched arms.

The young magician in the purple tunic

Spoke without a breath, like the dead,

He gave the queen of transgressions

All that made his soul feel alive.

And when the crescent moon began to sway

On the emeralds of the Nile and faded,

The pale-faced queen tossed

The flower glowing crimson for him.

A Hyena

Over the reeds of the sluggish Nile

Where only butterflies and birds fly,

A forgotten grave is hidden

Of a lawless but alluring queen.

The darkness of the night brings its tricks,

The moon arises like a sinful siren,

Whitish mists are spreading fast,

And a hyena is stealing out from its lair.

Its groaning is furious and vulgar,

Its eyes are sinister and gloomy,

And frightful are her bared teeth

On the pinkish marble of a grave.

“Look, moon, a lover of the reckless,

Look, stars, you beautiful visions,

And you dark Nile, the master of quiet water,

And you, birds, butterflies, and plants.

Look everyone, how my fur stands on end,

How my eyes gleam with evil fires,

Isn’t it true that I am, too, a queen

Like the one who sleeps beneath these stones?

Her heart once was beating full of betrayal,

Her arched eyebrows used to bring death,

She was the same hyena as I am,

She, like I, loved the smell of blood.”

In villages, dogs howl full of fear.

Little children cry in their homes,

And stern fellahs2 grasp

Their long, merciless whips in their hands.

Horror

I walked through corridors for a long time,

Around me silence lurked like an enemy.

Statues watched the intruder

From their niches with a hostile gaze.

Objects were frozen in some gloomy dream,

And strange was the gray twilight,

And like a foreboding pendulum

My lonely steps resounded.

And there where the dreary dusk was darker,

My blazing gaze was disturbed

By a barely visible figure

In the shadow of crowded columns.

I approached, and in an instant

Fear clawed at me like a beast:

I met the head of a hyena

On shapely maiden’s shoulders.

Blood was smeared on her sharp muzzle,

Her eyes were a gaping void,

And a vile hoarse whisper crept out:

“You’ve come here on your own, you are mine!”

Terrible minutes flew past,

And the gloaming spread,

While countless mirrors

Repeated the pale horror.

The Lion’s Bride

The priest made the decision. The people,

In agreement with him, knifed my mother:

A desert lion, a handsome god,

Waits for me in the savanna Paradise.

I am not fearful, would I hide

From the threatening enemy?

I put on a crimson sash,

Amber and pearls.

And here in the desert I cry out:

“Sun-beast, you have kept me waiting,

Come to rend into pieces

The human prey, my prince!

Let me shudder in your heavy paws,

Let me fall and not rise again,

Let me smell the terrifying odor,

Dark and intoxicating, like love.”

Grasses have the odor of incense,

I am quiet as a bride,

Above me is the murderous

Of my gold-colored groom.

The Plague

A ship is approaching Cairo

With the long banners of the Prophet.

Looking at the sailors, it is easy to see

They are from the East.

The captain shouts and scurries about,

His voice is guttural and raspy,

Swarthy faces and red fezzes

Can be seen in the rigging.

Children crowd on the pier,

Their thin bodies look comical,

They have gathered here at dawn

To see where the visitors will dock.

Storks sit on the roofs

And crane their necks.

They are higher than anyone else

And they can see better.

Storks are airborne magicians,

They understand many secret things:

For example, why one vagrant

Has purple spots on his cheeks.

Storks chatter above the houses,

But no one hears that they say:

Alongside perfume and silk

Plague makes its way into the city.

Giraffe

Today I can see your gaze is especially sad,

And your arms are especially lean, hugging your knees

Listen, my love: far off by Lake Chad

An elegant giraffe is roaming.

It is graciously slender and slight

And its skin adorned with a magical pattern

That can be rivaled only by the moon’s glimmer

Rippling and swaying on the surface of spacious lakes.

From afar, it resembles the colorful sails of a ship,

And its stride is smooth like the flight of a happy bird.

I am certain the earth sees many wondrous things

When at twilight the giraffe hides in its marble cavern.

I know joyful tales of mysterious lands

About a black maiden and the passion of a young chief,

But you’ve been breathing the heavy mist for too long,

You don’t want to believe in anything but the rain.

How can I tell you about a tropical garden,

About slender palm trees, and the smell of unimaginable herbs?

You’re crying? Listen… far off by Lake Chad

An elegant giraffe is roaming.

Rhinoceros

Do you see monkeys scurrying,

Screaming wildly, in the vines

That hang, oh, so low,

Do you hear the shuffle of many feet?

That means—very close to

Your forest clearing

An enraged rhino is lurking.

Do you see the general commotion,

Do you hear the trampling? There’s no doubt

If even the sleepy bison

Are retreating deeper into the mud.

But, since you are in love with the mystical,

Do not look for your salvation

In running away or hiding.

Raise your arms high

In a song of happiness and parting,

Glances, covered with pink mists,

Will lead your thoughts far into the distance,

And from the promised lands

Feluccas3 invisible to us

Will sail in to carry you away.

Lake Chad

On mysterious Lake Chad

Among the ancient baobabs,

At dawn carved feluccas

Swiftly carry majestic Arabs.

Along the lake’s wooded shores,

And by the green foot of the mountains

Maiden priestesses with ebony skin

Worship terrifying gods.

I was the wife of a powerful chief,

A daughter of imperious Lake Chad,

During winter rain I alone

Performed the mysterious rites.

They used to say that within a hundred miles

There wasn’t a woman more fair than I,

I never took the bracelets off my wrists,

And amber always dangled on my neck.

My white warrior was so graceful,

His lips so red, his gaze so calm.

He was a true chief;

And a door opened in my heart,

And when the heart whispers to us,

We don’t struggle, we don’t wait.

He said they hardly

Saw anyone in France

Who was more seductive than me;

And as soon as this day melts away,

He would saddle

A Berber steed for the two of us.

My husband chased us with his trusty bow,

Running through forest thickets,

Jumping over ravines,

Swimming across dusky lakes,

And death’s terror fell on him.

Only the scorching day saw

The corpse of the ferocious wanderer,

The one covered with shame.

And, astride a fast and powerful camel,

Drowning in a caressing pile

Of animal skins and silk,

I flew like a bird, to the north.

I broke my exquisite fan,

Reveling in ecstasy, in anticipation,

I parted the supple folds

Of my many-colored tent

And, laughing, leaned into the window,

I watched the sun dance

In the blue eyes of the European.

And now I am like a dead sycamore

That has shed all of its leaves,

I am an unwanted, dreary lover,

Like a thing, I am cast aside in Marseilles.

To feed on pitiful refuse,

To live, in the evening

I dance for drunken sailors

And they, laughing, take possession of me.

My timid mind is weakened by misfortunes.

My gaze dims with each passing hour.

To die? But there, in the fields beyond,

My husband waits unforgiving.

“From the distant shores of the Nile…”

From the distant shores of the Nile

The seafarer Pausanius4 brought

To Rome the skins of fallow deer,

Swaths of Egyptian fabrics,

And an enormous crocodile.

It was the time of the insane

Depravations of the Emperor Caracalla.

The god of the merry and carefree

Decorated capricious cliffs

With lines of noisy crowds.

In golden, innocent misfortune,

The sun was sinking into the sea,

And in purple garments

The Emperor has come to the sea

To meet the crocodile.

Bearded wanderers

Bustled by the galley.

And graceful hetaeras5

Raised their marble-like fingers

In honor of the goddess Venus.

And like some wondrous tale,

Like a spoiler of peace,

The crocodile glistened by the vessel

With its emerald-colored scales

On a silver pontoon.

Part II

From A Foreign Sky, 1912

By the Fireplace

A shadow floated in… The fireplace was burning out,

With his hands across his chest, he stood by himself,

With his gaze fixed far into the distance,

He spoke bitterly about his grief:

“I penetrated the depths of unknown lands,

My caravan has traveled for eighty days;

There were ridges of terrifying mountains, forests,

And sometimes strange towns in the distance.

More than once, in the evening stillness,

A faint howl reached our camp.

We cut wood, we dug trenches,

Lions approached us in the evening.

But there were no cowardly souls among us,

We shot at them, aiming between their eyes.

I dug out an ancient temple from under the sand,

And a river was named after me.

And in the land of lakes, five great tribes

Obeyed me and observed my law.

But now I am weak as though I were gripped by a dream,

My soul is ailing, it is gravely ill.

I have finally come to know fear,

Buried here among four walls;

Even the flash of a rifle, even the splash of a wave

Are not able now to break these chains…”

And, concealing evil triumph in her eyes,

A woman in the corner listened to him.

Abyssinian Songs

”Abyssinian songs” were Gumilev’s variations on the original folksongs that he collected during his travels to Abyssinia. Gumilev did not know the Ethiopian language, so the songs were translated for him into French and he then translated them into Russian. Gumilev claimed that the poems published in A Foreign Sky are his own works based on motifs from Abyssinian folklore, and he intended to publish the originals later.

I. A War Song

A rhinoceros tramples our durro,6

Monkeys steal away our figs,

But worse than the monkeys and the rhino

Are the marauder Italians.

The first flag was raised flapping over Harar,

This is the city of chief Makonnen.

Afterward, the ancient Aksum arose,

And hyenas began howling in Tigre.7

Through the forests, mountains and plateaus

Cruel murderers roam,

You, who slit throats, you

Will drink fresh blood today.

Steal your way from one bush to another

As serpents crawl to their prey,

Leap down swiftly from the cliffs—

Leopards have taught you how to pounce.

The one who obtains more rifles in battle,

Who sticks more Italians with a knife

Will be called by his people an askir8

Of the whitest horse of the Negus.9

II. Five Oxen

Five years I served a rich man,

I guarded his horses in the fields,

And for this, the rich man presented me

With five oxen, trained to the yoke.

A lion killed one of them,

I found its prints in the grass,

I should have guarded the paddock better,

I should have left a fire for the night.

The second ox became rabid,

Stung by a buzzing hornet, and fled

Five days I wandered in thick woods,

But I could not find the ox anywhere.

As for the other two, my neighbor poured

Poisonous henbane into their swill

And they lay on the ground

With their blue tongues sticking out.

I slaughtered the last one myself,

To have something to feast on

At the hour when my neighbor’s house was on fire

With the neighbor, all bound-up, screaming inside.

III. The Slaves’ Song

In the morning when birds awake,

When gazelles run out into the fields,

A European comes out of his tent,

Snapping his long whip.

He sits down in the shade of a palm tree

Wrapping his face with a mosquito net,

He places a bottle of whiskey next to himself

And whips the slaves whom he thinks are too lazy.

We must clean his clothes,

We must guard his mules

In the evening we eat salted meat

That went bad in the morning.

Long live our European master!

He has such long-range rifles,

He has such a sharp saber,

And his whip lashes so painfully.

Long live our European master!

He is brave, but so slow-witted,

He has such a delicate body,

It will be sweet to plunge a knife into it.

IV. The Women of Zanzibar

Once a poor Abyssinian heard

That far to the north, in Cairo,

The women of Zanzibar dance

And sell their love for money.

Long ago he became bored

With the fat women of Habesh,10

With the sly and evil women of Somali,

And with the dirty day laborers from Kaffa.11

And the poor Abyssinian set out

Riding his only mule

Over mountains, steppes and forests

Far, far to the north.

Thieves attacked him,

He killed four and escaped,

And in the Senaar’s thick forests

Hermit elephants trampled his mule.

Twenty times new moons had risen

Before he reached the gates of Cairo

He remembered then that he had no money,

And went back along the same road by which he had come.

Part III

From The Quiver, 1915

An African Night

Midnight fell, impenetrable darkness,

Only the river shines in the moonlight,

And beyond the river an unknown tribe,

Lighting campfires, makes a commotion.

Tomorrow we’ll meet and find out

Who’ll be ruler of this place,

They’re aided by the spirit of the black stone,

The golden cross on our neck helps us.

I again make the rounds between pits and mounds

Supplies will be here, the mules over there;

In this gloomy land of Sidamo12