8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

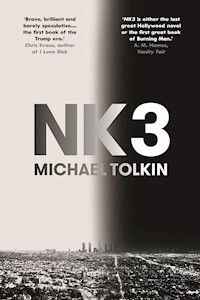

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A panoramic vision - suspenseful, comedic, prophetic - set in a near-future California that has been devastated by NK3, a memory-destroying virus from North Korea. The H LYW OD sign presides over a Los Angeles devastated by a weaponized microbe that has been accidentally spread around the globe, deleting human identity. In post-NK3 Los Angeles, a sixty-foot-tall fence surrounds the hills where the rich used to live, but the mansions have been taken over by those with the only power that matters: the power of memory. Inside the Fence, life for the new aristocracy, a society of the partially rehabilitated who call themselves the Verified, is a perpetual party. Outside the Fence, in downtown Los Angeles, the Verified use an invented mythology to keep control over the mindless Drifters, Shamblers and Bottle Bangers who serve the gift economy until no longer needed. The ruler, Chief, takes his guidance from gigantic effigies of a man and a woman in the heart of the Fence. They warn him of trouble to come, but who is the person to watch: the elusive Eckmann, holed up with the last functioning plane at LAX; Shannon Squier, the chisel-wielding pop superstar from the pre-NK3 world, pulled from the shambling masses; a treacherous member of Chief's inner circle; or Hopper, the uncommon Drifter compelled by an inner voice to search for a wife whose name and face he doesn't know? Each threatens to upset the delicate power balance in this fragile world. In deliciously dark prose, Tolkin winds a noose-like plot around this melee of despots, prophets and rebels as they struggle for command and survival in a town that still manages to exert a magnetic force, even as a ruined husk.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Also by Michael Tolkin

Novels

The Return of the Player

Under Radar

Among the Dead

The Player

Screenplays

The Player, The Rapture, The New Age: Three Screenplays

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2017 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © Michael Tolkin, 2017

The moral right of Michael Tolkin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, entities or persons living or dead are entirely coincidental.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 518 0

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 947 8

Printed in Great Britain

For Wendy Mogel

Inhalt

NK3

Colonel Lee, Sergeant Jun

Hopper, Hopper’s Silent Voice

Erin, Stripers, Seth, Seth’s Silent Voice

Marci, Eckmann, AutoZone, Tesla, Carrera

Seth, Dr. Piperno, Erin, Carrera

The Woman, The Man, Chief

Dr. Kaplan, Dr. Piperno

Hopper

Marci, AutoZone, Tesla, Carrera

Chief, Frank Sinatra, Pippi

Marci, Eckmann, Tiny Naylor

Dr. Kaplan, Dr. Piperno, Sarabeth

Hopper

Seth, Marci, Eckmann, Franz

Chisel Girl, Frank Sinatra, Justin

Hopper

Erin, Chisel Girl, ElderGoth, Chief, Sinatra

Chief, Pippi Longstocking

Frank Sinatra, Redwings, Chief, Shannon Squier, ElderGoth, Erin

Seth, Marci, Franz, Eckmann

Hopper

Franz, Eckmann, Spig Wead, Seth, Marci

Shannon Squier, Erin

Hopper

Chief, Shannon, Erin, Helary, Jobe

Hopper, Viola, Made In USA

Chief, Pippi, Committee Heads, Shannon, Erin

Hopper, Madeinusa, Tesla

Frank Sinatra, Redwings, Chief

Chief, The Man, The Woman, Erin

Eckmann, Marci, Seth, Franz, Spig Wead

Frank Sinatra, Gunny Sea Ray, Redwings

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee, Martin Rome, 18 Tee

Chief, Pippi

Frank Sinatra, AutoZone

Eckmann, Franz, Spig Wead, Consuelo

Chief, Pippi

Siouxsie Banshee, Redwings

Shannon, Erin, Jobe, Helary, Toffe

Chief, Toby Tyler

Eckmann, Marci, Consuelo

Hopper, Madeinusa

Shannon, Erin, Toffe

Hopper

Eckmann, Crew

Chief, Pippi, Frank Sinatra, Redwings, June Moulton, Toby Tyler, Erin, Shannon Squier, Gunny Sea Ray

Shannon, Erin, Helary, Jobe, Toffe

Go Bruins, Royce Hall

Hopper, Silent Voice

Eckmann, Franz, Spig Wead

Pippi, Go Bruins, Royce Hall

Hopper, Silent Voice

Shannon, Bottle Bangers, Drifters, Siouxsie Banshee, Frank Sinatra

Eckmann, Marci, Seth Kaplan, MD

Pippi

Eckmann, Spig Wead, Franz

Shannon, Chief, Bottle Bangers

Pippi

Chief, Vayler

Erin, Shannon

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee,June Moulton, Chief, Shannon

Vayler

Hopper

Chief, Go Bruins, Pippi, Shannon, Erin

Eckmann, LAX Crew

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee

Shannon, Erin

Hopper, Visitors

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee

Vayler

Hopper, Seth, Marci

Hopper, Seth, Stranger

Frank Sinatra, Security Committee, Pickle

Mr. and Mrs. AutoZone

Shannon, Erin

Hopper, Seth Kaplan, Paolo Piperno

Pickle

Pickle, Vayler

Chief

Redwings, Gunny Sea Ray, Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee

Chief, ElderGoth, Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee, Redwings, Gunny Sea Ray

Chief, Go Bruins

Pippi, Go Bruins

Hopper

Shannon, Erin, Toffe, Brin

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie, Redwings,Gunny Sea Ray

Frank Sinatra, Chief, Go Bruins, Royce Hall

Pippi

Frank Sinatra, Gunny Sea Ray, Redwings, The Man

Hopper

Chief, Frank Sinatra, ElderGoth, Toby Tyler, June Moulton, Vayler, Hopper

Frank Sinatra, Vayler Monokeefe, Hopper

Pippi, oranges chief

AutoZone, Mrs. AutoZone

Siouxsie Banshee, Frank Sinatra

Hopper, Seth, Piperno

Shannon, Erin, the Stripers

Pippi

Siouxsie Banshee, Frank Sinatra

Gunny Sea Ray, Hopper

Vayler

The Woman

Shannon, Helary, Erin

Chief

The Playa

Siouxsie Banshee, Vayler Monokeefe

Chief, Go Bruins

Hopper, Gunny Sea Ray

Chief

Siouxsie Banshee

Chief, Hopper, Shannon Squier

Chief

Frank Sinatra, Siouxsie Banshee, Redwings

Shannon Squier, Erin

Hopper

Pippi

The Teacher

Robin

Siouxsie, Frank Sinatra, Redwings

Chief, oranges chief

Acknowledgments

It really was as if the so-called “human” qualities had been characteristic features of a period of human history long past and were now only to be found on tombstones, as inscriptions for the dead.

Joseph Roth, The Silent Prophet

Colonel Lee, Sergeant Jun

It was a warm night in the bunker and Colonel Myung Lee was worried about money. “Boarding school is expensive, Sergeant Jun,” said the Colonel, but Sergeant Jun knew it really wasn’t the money. The Colonel’s son had been accepted at Daewon Foreign Language High School near his home in Seoul and expected to go there, but a space had just opened up for him at Korean Minjok Leadership Academy, the boarding school a half-day’s drive from the city. His best friend was going to Minjok and the boy wanted to go there with him. The Colonel rattled with indignation. “Daewon costs five thousand dollars a year and Minjok costs fifteen thousand. Ten thousand more for food and a bed? Does that make sense, Sergeant Jun?” Jun agreed it seemed excessive.

The Colonel had been in charge of this outpost since before Jun had enlisted. Due for a transfer to the capital, he wanted nothing more than to stay at home and see his son every day. But if the boy went away to Minjok, the Colonel would never again have the time to be close to him since most of the graduates of both schools went to university in America. Before he departed for such an exciting world of opportunity, Colonel Lee wanted to leave his son solid memories of good days together and was scared that this would never happen if the boy went to Minjok Leadership Academy.

“I told my wife, if he’s going to get into an American university, I don’t want him going to one of the schools on the Atlantic side of the country. I want him in Los Angeles or San Francisco. Berkeley and Stanford are there. Those are very good schools. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Oracle, Facebook, these are all in California. My wife says, ‘But what if he gets into Cornell? What if he gets into MIT? You want to hold him back from a great university because the flight is five hours longer?’ Then I say, and Jun, I know this is wrong, I say, ‘America doesn’t matter so much anymore. A Korean education is in many ways superior, especially in technology. Remember, the Americans buy the TV sets we make here. We don’t buy theirs.’ And she says, ‘Just admit to yourself that you’re going to miss him. I’m going to miss him too. And if he didn’t score so well on tests, if he wasn’t such a strong tennis player, then he wouldn’t be accepted by Minjok, and then he wouldn’t be on his way to a great American university.’”

It was Sergeant Jun’s burden that the Colonel confided in him. He worried the Colonel might one day regret this late-night fraternization and find some excuse to punish his subordinate for having answers to questions about the Colonel’s private life that the Sergeant had never asked. But he had no choice about the assignment. On the nights when the Colonel was senior duty officer, he made sure that Jun was beside him watching the monitors for activity on the north side of the DMZ. Jun understood what the Colonel’s wife meant about the Colonel’s need to admit things to himself. It was Jun’s experience of the Colonel that he exaggerated to the point of impersonation the stubborn skepticism of a career soldier for whom all problems are merely logistic as a way to pretend he wasn’t in fact a complicated man. Jun had the passing thought more than once that the Colonel was infatuated with him for reasons the Colonel could not express without stirring up the cistern of his own emotions and that the Colonel found excitement, too much excitement, in the exercise of his restraint.

After a moment of quiet, the Colonel confessed, “She’s right. I’ll miss him. She’s right. It doesn’t matter if it’s Boston or San Francisco. Why should I be cross with him for leaving home? You and I left our homes, right, Jun? We traded the warmth of family life for the glory of war. Look at how we traded family life for the dreadful machinery of war!” He pointed at the electric kettle, with its setting for herb tea, green tea, and black tea.

Jun laughed quietly at this. The Colonel used his rank to exercise irony, but it was risky for Jun to make humor out of their situation, not for fear of political reprisal. It was their opposites in uniform on the north side of the fence—along the mined strip of negative space that stretched from one coast of Korea to the other—who couldn’t openly discuss the truth of their absurd situation for fear of dreadful punishment. No, the danger of levity in this bunker was that it would open these defenders of the free world to the pointlessness of their mission. And if their job was pointless, why weren’t they home in Seoul adjusting, perhaps slowly, to the forfeit of rank, bored by mundane reality, but at least watching their children grow up? The North would never invade with its army because China, dreading chaos and refugees, would let the United States defend the South and the North would lose. Everyone knew this. No one could say it.

The command phone rang. Jun answered. Seismic detectors were picking up an increase in normal activity directly across from them, possibly from previously unknown North Korean tunnels. About this kind of alarm, the Colonel was never casual. And for all that Jun worried that their familiarity would provoke trouble in some form, Colonel Lee’s response to an alert instantly turned every false alarm into an adventure.

Jun drove the Colonel the three kilometers to the scene. It wasn’t a surprise to see a platoon of North Korean soldiers approaching the fence on their side of the empty zone; both armies played the same game of posturing. But there was something different about the shape of the North Korean soldiers.

Jun told the Colonel: “They’re wearing hazardous materials suits, Colonel, enclosed circulation.”

“Are any of them not wearing those suits?” asked the Colonel.

“None that I can see, sir.”

“Weapons?”

“None visible, sir.”

“No sidearms?”

“None visible, sir.”

Lee asked for the field phone and woke up the General, who, like Jun, didn’t for a moment think Lee’s call was out of unnecessary caution. “Fifty men in hazmat suits across from Outpost Twenty-Three, sir. Consistent vibration suggesting tanks in a tunnel.”

The opposing outposts shared a ridge. A fire truck drove up to the North’s outpost and stopped, leaving the motor running. The driver of the fire truck was also wearing a hazmat suit.

Lee narrated: “They’re raising the ladder.” It had a stainless steel water cannon at the end next to a long orange windsock that filled as the ladder lifted it into the breeze that came from the North.

The ladder extended five lengths.

“Jun, what is the angle of that ladder and is it crossing over the line of their fence?” asked the Colonel.

“At least seventy degrees, and . . . no . . . it’s completely on their side. It might be a fire drill.”

“Why wear hazmat suits for a fire drill?”

Two men in the suits carried a hose to the top of the ladder and twisted the fitting onto the cannon. Immediately they turned on the water, which came out in a wide spray, not a long tight stream.

Colonel Lee told the General: “They’re spraying something into the air directly above them, and the wind is carrying the mist across the DMZ. I can feel it on my skin. It’s an attack. It has to be an attack, but what’s our response?”

Hopper, Hopper’s Silent Voice

Hopper was asleep in an underpass when the sound of the first bus entered his dream, and then the dream melted into one of those invisible mental tapestries he called Thought Pictures. His Silent Voice didn’t talk about them. He saw a big yellow dog and a smiling woman in the Thought Picture. He didn’t have many Thought Pictures like this. The dog, a group of boys playing basketball, Hopper shooting and scoring.

Another bus followed the first. He grabbed the binoculars from his bicycle’s saddlebag, crawled up the embankment, and watched as the buses drove down the freeway off-ramp a hundred yards away. The buses then continued a mile down the road that led to the mountain. Furrows of rippled sand covered the blacktop.

Hopper read the words stenciled on the buses. THANK YOU founders FOR THIS GIFT—THERE IS NO EQUAL VALUE—LEAVE NO TRACE—INCLUDE THEM—yes YOU’RE HERE!—PARTICIPATE!—no branding—sustainability now

The buses stopped and the doors opened. Two women left each bus and then stood by the door as the passengers walked out: more men than women, all of them quiet except for the times when they hummed in unison, one setting a random pitch and the others finding it. The women made the passengers form two straight lines, facing away from the buses.

The women then returned to the buses, the doors closed, and the buses returned to the freeway, driving west.

The two lines stayed where they’d been placed. Hopper asked his Silent Voice if it was safe to move closer.

“Leave them alone. You can’t help them and they can’t help you.”

Ignoring his Silent Voice, Hopper rode his bike nearer to them, pushing hard to move through the sand.

A few of the Drifters looked at him, smiling with a blank familiarity.

Another four buses came down the road. His Silent Voice told him to get away.

The lead bus stopped and someone inside it pointed a rifle at Hopper and started shooting.

Hopper’s Silent Voice said, “I told you it wasn’t safe to stop here. Ride toward the mountain.”

There was no straight line to follow between the rocks and the clusters of brush. Hopper didn’t look back until he dropped down the side of a dry riverbed and disappeared from the view of the men who were shooting at him.

The Drifters scattered during the shooting. Their lines were broken and they spread out in all directions panicked, except for the Shamblers—the more degraded among them—who shuffled in small circles or stood in one place with no reaction to the noise. The shooter stood on top of the bus, scanning the gullies with his own set of binoculars. He took a few shots at what he thought was there. He climbed down from the roof and consulted with the others.

The sun was setting. They turned on their headlights and drove away.

Hopper had done everything the Teacher had warned him against doing.

“I trust you to do what’s right and your Silent Voice will help you. Listen to him when he speaks.”

He waited for the deep part of night and walked the bicycle back to the freeway, past Shamblers stumbling in the dark looking for something to eat.

There was sand on his chain and his gears slipped when he shifted. He wasted two hours walking through an outlet shopping mall, looking for a sporting-goods store and a new bicycle. The next town was five miles away. He would stay out of sight on a road parallel to the freeway. If he found a bike, in two days he’d be in Los Angeles, where he would look for his wife. If he found her and she didn’t have a bicycle he would get one for her and they would ride back to Palm Springs and he could introduce her to his Teacher.

The Teacher had said it many times: “Your wife is in Los Angeles. If you want to find her, you have to go there. It won’t be easy but I can help you. How long have we known each other, Hopper?” asked the Teacher. It was a question he asked often, and Hopper always had the same answer.

“Forever.”

Erin, Stripers, Seth, Seth’s Silent Voice

When you are nineteen years old and pretty, every day in Center Camp is an adventure in advanced perfection. So how wrong was it for Erin to wake up angry because some rude person was banging on her door? She shouted a yawp of annoyance and then the door was open and Brin, Jobe, Helary, and Toffe—who never spoke—looked in at her. With Erin, they were Center Camp’s first fivesome, and called themselves the Stripers for the white-and-red-striped stockings they took from Inventory whenever a convoy returned with them. Only last week, the sharp scouts from Inventory returned with a carton of striped socks from an overlooked Target distribution depot in San Bernardino. And while most of the socks were blue and white, instead of the preferred red and white, no one but Erin’s squad was going to get any of them. Brin, always the first among equals below Erin, threw a Red Vine at Erin and said, “We’re leaving for the DMV in fifteen minutes. Inventory found another eleven Drifters around Long Beach, and Chief wants them all processed today.”

This would be Erin’s third trip this week to the DMV—the Department of Mandatory Verification. This was sometimes called the Department of Mental Verification, or Manual Verification. Until four years ago it had been the Department of Motor Vehicles, Hollywood branch. June Moulton from the Mythology Committee, the committee’s only member, said it was always a good sign when something that used to mean one thing could now mean something entirely new. She had no other examples. The heads of committee each had their own mansions in Center Camp, except for June, who shared this house with Erin, though claiming the master bedroom. Brin and Helary thought the room should be Erin’s because the house had always been Erin’s, not just in the new or recent now. It was where she lived with her father and mother, when she still had them.

Erin was nineteen by the old calendar, but by the only calendar that mattered she was four. In the known world, by the new calendar, four was ancient. The new calendar four-year-olds had been rehabilitated four years ago by the best doctors in the city. They had been given the kind of attention and thorough cortical stimulation—three weeks in a controlled coma—that was no longer possible since the best doctors themselves were gone and the replacements they had trained didn’t understand the subtleties of the machines and drugs, or were forced to abbreviate the cure because the drugs had run out. The scale of the disaster obliged them to focus on the minimal rehab needed for the Systems Committee to continue without falling apart. Systems, the largest committee, meant Toby Tyler and her crew, the master civil engineers. They were granted the privilege of rehab even before medical specialists. There was no Medical Committee. Plus, and this isn’t a small thing, no one can run a smashed rehab machine.

The daughter of privilege, born lucky, Erin’s good fortune continued even when she was one of the first three hundred people in Los Angeles to be diagnosed with what was then called Seoul Syndrome Release 3.0. The first puzzling and awful symptom hit her thirty-two hours after a long night at a karaoke bar in Koreatown. There she was, walking in a corridor at her high school, when she felt the unfamiliar awakening of her soul’s recognition of God’s love, and with that, galaxies of old resentments rolled out of her—memories of insults and bad grades and rejection and envy—like a movie reel unspooling into a fire, and in the empty space left by all that crap, she fell into an infinity of peace. She tried to explain this feeling to everyone around her in the school corridor, where no one ever talked about the love of God. In the school nurse’s office, the first assumption was that she was high on ecstasy. But then she kept saying good-bye to memories, as she watched them take to the air like a flock of swallows leaving a disappearing barn and disappearing into a disappearing sky. She failed the basic mental status exam: time, place, count backward, who’s the president. The evil of the syndrome was that the victims felt relief as NK3 swept through their brains, before wiping them out. When the area’s emergency rooms compared notes after the first hundred cases, the Centers for Disease Control broadcast the description of the disease, which matched the epidemic marching through Asia. When Erin’s father, the president of Warner Bros., understood what had invaded his baby girl he called UCLA hospital’s chief of surgery and asked for the kind of favor typically and not covertly granted the charitable president of a studio, to put Erin at the head of the line for the first available bed in the SRC, the Syndrome Rehabilitation Center.

June Moulton was in the next bed, and after rehab, June—age not certain but probably in her midforties—kept close to the young Erin, who neither welcomed her nor pushed her away. It was possible June was her father’s mistress.

June Moulton had tried to teach the mass of Drifters a story that would explain what they were doing and give them a sense of purpose that could be translated into devotion. She left out NK3 and told the story of a race of giants who built the cities and bequeathed the Gift Economy, all the food in the supermarkets and warehouses and the farms too, before they moved to a place behind the clouds. She had trained a cadre of Inventory specialists to give lectures on the city’s history, using the old churches after taking down the Christs and crosses. June hoped that giving the Drifters a history would make them loyal to an idea, and from there the Mythology Committee could elaborate a bigger story and transfer that loyalty to the First Wave directly. But like so much of the mental effort in this four-year-old world, there were gaps in logic, leaps of coherence. June believed that forgotten mythologies of the world before NK3 had done no better when the world lived on the Theft Economy.

The SRC started in a suite of three rooms in the main part of the hospital and then moved to the psychiatric ward, forcing the expulsion of all the teens in the eating disorders wing. It then moved to the floor of the basketball arena, which had room for an additional five hundred beds. Twelve weeks later, as the syndrome spread, no connections would have helped. After six months, no one remembered what Warner Bros. was, not even the president of Warner Bros. Before the senior specialists in the syndrome fell to the implacable rule of the disease, they named it NK3.

Toby Tyler and her crew of supervisors from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power selected their best workers. Wind farm crews were put to work setting up power generation close to the city. All the phone systems were dead because they ran on central computers, but there were walkie-talkies in every film studio and the Systems crew set them up to work as far as sixty miles from Center Camp.

After two months, not even Erin’s father himself could have taken a rehab bed away from a roofer who knew how to install solar panels. Rich men offered everything they owned to be saved, but without the highly specific skills that keep the world’s wheels turning, the real wheels, their brains were abandoned to the mandibles of North Korea’s weaponized nanobacterium. The doctors should have taken care of each other, but when they finally understood the crisis, most of them had forgotten what to do. Each freshly trained rehab specialist understood less about the process and the machinery and the tolerances than the one who came before, until finally someone with five days of training couldn’t even ask for help from a doctor with twenty years of experience, because it was all forgotten. And then, so it was later told to those outside the Fence by June Moulton, the machines fell apart from so much use and no one else could be saved.

As June said, “It was not betrayal, no. The opposite. Thank them for this gift. There is no equal value.” With the best intentions, the final wave of the Rehab Committee broke the machines trying to make them work. That was when the Founders showed Chief how to protect the saved from those who could not be saved. Following their instructions, Chief organized the construction of a wall of steel, concrete, bricks: anything a contractor could pull together with a rehabbed construction crew, a sixty-foot-tall barrier surrounding the range of low mountains that divided the basin of Los Angeles from the San Fernando Valley. Downtown Los Angeles was left to those not admitted to the society of the useful.

In honor of the Founders, the Playa was cleared and the statues of The Man and The Woman were erected so the Founders would never be forgotten.

Erin had photographs of her father so she knew what he looked like, but she didn’t remember him. And she never had a thought about finding him—if he was alive—since he was a stranger to her. Indifference was the special cruelty of the syndrome’s design. Erin’s brain tossed up a few detached memories from the old days but they weren’t felt as memories with an emotional connection, in the way she remembered sex with her friends the next morning. No, these fragments came in like the interference of someone else’s conversation on walkie-talkies when signals were crossed on shared frequencies. She lived in the house in which she was born but didn’t remember anything about it before she got sick.

She had been drilled by the leaders that her duty to honor her father was through dedication to doing something useful, but for the first two years she had been nothing more than the hub of the society of those other young orphans who were verified but had no skills to offer the community. Like everyone who was verified, since only the First Wave was trusted with the food grown inside the Fence, she worked one day a week on the farm, where the oranges, avocados, lemons, persimmon, carrots, and lettuce grew, but Systems was in charge of the irrigation and there wasn’t much for her to do there but pull out the weeds.

She wrapped an elastic band around her purple dreadlocks, put on a white ruffled skirt, striped knee socks, and cowboy boots. She crossed two Flintstones Band-Aids over her nipples and finished off the outfit with a fuzzy white vest. This is what every girl wears, but no one denies that Erin was the first.

Brin and quiet Toffe were verified university students who had forgotten their majors: math and history. They floated among whatever jobs amused them for however long. Jobe was verified but lacked an employment designation so no one was quite sure about what he had done. Helary, probably twenty-five, was a verified pharmacist, her usefulness diminished because most pharmaceuticals were past their expiration dates. The antibiotics were dead. The painkillers were unreliable. The antidepressants and antipsychotics might have been as fresh and effective as the day they were minted, but the brain damage suffered by the victims of the plague changed the synaptic switches the drugs were designed to fix. The serotonin and dopamine receptors as redesigned by the genomic-modification wizards of Pyongyang were invisible to the old remedies.

Erin was good at recognizing past social differences, a skill—if that’s what it was—that no one on any of the committees (Systems, Verification, Security, Inventory, Mythology) regarded as having value until a squad from Inventory found the incomplete database of registered drivers on the computer at the Hollywood office of the Department of Motor Vehicles. The computers couldn’t be moved because no one had the skill to trace the cables that linked the cameras with facial recognition software to the servers where the information was stored. The Fence’s closest gate was two miles away, and the Security Committee, with Chief’s concurrence, ruled that it was safer to build a strong barrier around the DMV than to expand the great Fence.

Center Camp, in the old days, had been Beverly Park, a private gated community of sixty mansions in a little valley at the top of the hills. Before the changes, the mansions cost thirty million dollars for thirty thousand square feet with ten bedrooms and fifteen bathrooms, and kitchens large enough to feed the wedding party of a billionaire’s daughter. There were screening rooms and wine cellars. The wine cellar cooling systems needed too much electricity and were disconnected. The houses were assigned by rank and seniority. Chief lived in the redbrick palace on the leveled peak, the highest point over Center Camp. The view took in the long ridge that started beyond the Fence, fifteen miles to the west, at the ocean in Santa Monica. To the east, the ridge continued through Hollywood and ended a little north of downtown, at the LA Dodgers stadium and massacre site. Between the hills and the wall of the San Gabriel Mountains to the north were the Burn Zones of Encino, Van Nuys, Northridge, North Hollywood, Panorama City, and Sunland. They extended to the east, almost to Palm Springs. No one was allowed to explore the desert.

The view from Chief’s terrace included all of this and more on a clear day, and most days were clear. The view to the south swept from Santa Monica south along the coast to Long Beach, forty miles away. The next controlled Burn Zone outside the Fence was still being prepared: from the USC campus to West Adams, Crenshaw, the Byzantine District, La Brea, the lower parts of Baldwin Hills, and Culver City. South of that was LAX, the airport. Chief had waited three years to attack the airport and after the coming Burn, he was sure he could face the airport’s guns and, in a fast enough strike, keep the LAX crew from destroying the remaining twenty-three jets parked on flat tires around the terminals.

The van left through the Fence’s East Gate into Hollywood, now mostly abandoned, bulldozed, and burned. Two blocks from the DMV, Erin waved at the shambling Driftette with the typically flattened expression who shook a broom to greet every vehicle going past the Honda dealership, which was now the DMV motor pool garage. The Driftette had been the motor pool mascot for a few months, and Erin, usually indifferent to Driftettes but tickled by the mascot’s dull-eyed enthusiasm, always waved back at her.

Then they arrived at the old Department of Motor Vehicles, a broad parking lot now surrounded by a cinder-block wall inside double chain-link fences wrapped with razor wire. They stopped beside the Christina, a sixty-five-foot wooden cabin cruiser built around a truck chassis. The stern of the boat carried a message: THANK YOU FOUNDERS FOR THIS GIFT.

The Inventory bus with the day’s Drifters still inside waited for the DMV to open. Erin and her friends entered through the back door and she took her seat behind the registration counter with its computer terminal and camera. Brin and Jobe took their seats along the same counter. Quiet Toffe sat behind Jobe. There were only nine men and two women on the day’s assignment sheet. They’d been picked up twenty-five miles from downtown, living together in the same house. The area had already been swept for Drifters, so they had either been overlooked, or had grazed their way up the coast from San Diego.

The Drifters were presented as they’d been found, not washed or shaved, in the clothes they’d been wearing.

Erin’s first intake was like her second and third intakes, slow to answer the questions: Do you know your name? What’s your first memory? Do you know where you are? And so on. Their pictures were taken, uploaded into the system, and if there was no match in the database, they were sent to live downtown, where they were fed and housed for as long as Systems or Inventory needed help. And then? The desert.

Erin’s fourth intake was a man in short khaki pants and a T-shirt from a surf shop in Santa Monica. He was sunburnt, with long matted curls of light brown hair streaked with gold highlights. Erin saw Toffe look over at him with an expression that said she would kill, kill for those highlights. He might have been a surfer at one time, but a T-shirt was proof of nothing.

Like most Drifters, he needed to be told to sit.

“We go to the same barber,” said Erin, shaking her dreadlocks.

He didn’t respond. Of course not.

She told him not to move while she took his picture and uploaded the photograph. He didn’t ask anything about what she was doing or where he was.

“I’m Erin,” she said. No answer. Few Drifters talk to each other and some of the newcomers had not spoken full sentences in four years.

“Do you know where you are?”

“They didn’t tell me.”

“Who didn’t tell you?”

“Them. The people. The man in the bus.”

“The bus driver?”

“Yes.”

“He didn’t tell you where you are?”

“No.”

“Where were you yesterday?”

“The place. The house. Yes?”

“Are you asking me if I know where you were yesterday?”

“I don’t know.”

“There’s no right answer. There’s no wrong answer. Tell me about your T-shirt. Where did you get it?”

“A place.”

“Did you ever surf?”

“What?”

“Did you ever go in the ocean and ride that board on the waves, and stand up?” Breaking the rule forbidding all but minimal physical contact, she poked the surfboard on the T-shirt.

“Is that me?” He touched the man on the board.

“It could be,” said Erin. “What’s your first memory?”

“I was walking this morning when the bus stopped and the people told me to get inside.”

“That’s your first memory today, but what’s your first memory ever? What do you remember from when you were a little boy?”

He had no answer. She asked him to turn his face from one side to the other. He hesitated, and rolled his eyes to one side, looking over his shoulder without turning around.

“Do you have a Silent Voice?”

“What’s that?” He said this without asking his Silent Voice how to answer her question.

“No one is sure exactly, but some people who were given short turns in rehab hear a voice that doesn’t go away. No one understands more about it than that. Do you hear someone guiding you?”

“No.”

His Silent Voice commended him: “Good answer.”

“Silent Voices tend to tell their hosts to lie about everything. I’m in the First Wave, first of the First as we say, so I don’t have one, but I have friends who do. It happens even to late First Wavers. No worries. You look pretty well fed. Where did you eat?”

“In a big building.”

“I bet,” she said, but not really listening to him because the computer had found a match.

This was always a moment that demanded caution. Erin tossed this question to him without putting emphasis on its importance. “Does the name Seth Kaplan mean anything to you?” she asked.

“No.”

“One Forty-Eight South Windsor Boulevard, does that address mean anything to you?”

“I don’t think so.”

“You don’t think so or you don’t know?”

“I don’t know.”

“October seventeenth, nineteen eighty? Does that sound familiar?”

“No.”

“You used to wear glasses. Do you know what happened to them?”

“No.”

“MD. Do you know what that stands for?”

“Stands for?”

“Let me explain what’s happening. My computer links to a database that belonged to the California Department of Motor Vehicles. It uses facial recognition software to find matches to the pictures we take here. It just found a match to your picture, proving that you are Seth Kaplan, MD. This could be good for you, but my supervisor has to look at this before we can be sure.”

Erin called to Toffe to get ElderGoth, the head of the Verification Committee. She was the only committee head to live outside the Fence, but she’d been a computer technician before everything happened and Chief wanted her to stay at the DMV, on the chance that if the verification computer broke, she’d know how to fix it. ElderGoth spent most of her time in an Airstream trailer attached to the building. She came out, her corset loose over a tired black velvet dress, and she wasn’t wearing her usual uniform of fishnet stockings and the angel wings made of crow’s feathers stapled to an elastic harness around her shoulders. Erin had never seen ElderGoth without the black wings, and the committee head apologized before Erin asked why she was so informal today. “My three best dresses are all tearing at the seams like they were following a schedule. Vayler Monokeefe says Inventory has already gone through every vintage clothing store between here and wherever. My wings are falling off the thing that holds them together and there’s nothing left for me to wear, unless I want to wear stuff that’s new and you can imagine what I said to him. I don’t believe they search hard enough, and this is not how to treat a committee head. What do you have here?” She looked at the Drifter and then at the photograph of Seth Kaplan, MD.

“Hold his hair away from his face.” ElderGoth looked into his eyes and back to the picture on the monitor. “Good work, Erin.”

ElderGoth took Seth’s hands in hers. “Dr. Kaplan, I’m ElderGoth, head of the Verification Committee, and I want to welcome you. Because your face matches up with the system, and you have a skill that we need, you are now going to join the community of other verified people as though you were First Wave from the beginning. You will no longer have to sleep in cold houses and eat whatever you can scavenge from supermarkets and grocery warehouses. You will no longer have to run from packs of coyotes and wild dogs. No predators are ever again going to steal things from you or hurt you or do things to your body that you don’t like. The Founders have left us with food for many years. Only Inventory knows for sure but it’s somewhere between twenty and a thousand years. So instead of being what was once a Productive Economy, we are now, instead, in replacement, a Gift Economy. We give freely to each other expecting nothing in return. What you need you get and because of this, you are no longer greedy. How’s that?”

“How’s what?” asked Seth. “You said a lot of things. Which one of the things you said is the thing you said is ‘that’?”

“The community is going to do everything it can to help restore your old skills. How does that sound, Dr. Seth Kaplan?”

His Silent Voice said, “You don’t know yet.”

He didn’t answer. Erin said, “He’s happy. I can tell. Thank the Founders! You’re here!”

“I’m here.”

“Yes,” said Erin. “There’s one more thing we have to do.”

ElderGoth left for a minute and she returned with a metal rod, about two feet long, in one hand, and a butane torch in the other. She used the flame to heat the end of the rod.

Erin and Jobe grabbed the doctor’s left arm and pressed it onto a table. Before he had the time to ask his Silent Voice what was happening, ElderGoth pressed the hot end of the rod into the inside of his left wrist. He cried out.

“It heals fast,” said ElderGoth. Before Erin wrapped the burn in gauze, Seth saw the mark:

Marci, Eckmann, AutoZone, Tesla, Carrera

Two blocks from the DMV, the motor pool mascot swept the garage floor. She found two washers and a bolt and put them in the right containers on the tool bench. She almost never found anything small on the floor, because AutoZone kept the shop organized and had trained Carrera and Tesla not to get sloppy. But neither of his assistants wanted to sweep. The motor pool crew called her Hey You. Carrera wanted to name her Hey Stupid and Tesla thought Suck Me might be funny, but AutoZone disagreed. “If we give her a joke name and she ever figures out we’re making fun of her, she might leave. And she sweeps up better than either of you. Or me. She answers to Hey You, so that’s what we’ll call her.” AutoZone ran the motor pool. The decision was final.

Hey You picked up a flat-head screw and then got back down on her knees and pretended to feel for more in the shadow under a workbench where she used the screw to scratch off a line marking the ninety-seventh day she had been at the garage pretending to be stupid. Her real name was Marci, although no one had called her that in ninety-seven days, and ninety-seven was a guess. She might have scratched the same day twice, and she was sure she’d missed it a few times.

Eckmann and his crew of sixty had worked for four years to keep the Boeing 787 Dreamliner from Singapore Airlines ready to fly, lacking only a pilot who knew the plane. The Dreamliner in the hangar was the only functional plane at LAX. The twenty-eight planes still parked at the terminals would never fly again. The last planes to escape flew off over three years ago and even if they had landed safely somewhere, there was no way to let anyone know, or, as Eckmann said, no reason.

Then the Canadian showed up at the perimeter, in uniform, with airline identification. He hadn’t sought verification at the DMV but said he wanted to fly away. Eckmann trusted that with enough time in the cockpit, the Canadian’s skills would return, but he couldn’t make sense of the cockpit no matter how many hours he sat in the pilot’s seat and finally Eckmann gave up forcing him to try. Eckmann threw the Canadian off the hangar roof. With no pilot or prospect of escape, the hangar crew was afraid that Center Camp would send a raiding party, but Eckmann promised them that Chief knew Eckmann would blow up the Dreamliner before he surrendered. In the days of chaos, a battalion of national guardsmen had surrounded the airport with land mines and rockets—in the interest of national security—to keep anyone from hijacking a jet. Then the national guardsmen, without authorization, took two jets and left the airport to Eckmann.

Marci had been a flight attendant for United Airlines, based in Atlanta, and was on turnaround at the airport the day the first infected plane came in from Seoul. She joined the community of the hangar, sweeping up the floor.

After killing the Canadian, Eckmann told Marci to meet him on the runway when it was dark. “This isn’t for sex.”

Marci found him on a blanket in the middle of the long runway that only needed to be swept of debris to be ready for the jet to take off. Eckmann offered Marci a small bottle of Absolut Vodka. There weren’t too many of those left and he never offered the Absolut except to reward someone for a great contribution to the community. Marci wasn’t sure of what she’d done to deserve this. He was in one of those moods, she knew, in which it was better to let him speak instead of asking him questions. He told her to lie down and open her arms.

She expected a kiss, or more, but nothing followed. “Now look up at the sky and pretend you’re looking down. And instead of thinking that you’re held in place by whatever keeps us on the ground, you’re about to fall off the ceiling and you’re going to keep falling.”

“I can do the part where it feels like I’m looking down, but not the part where I feel like I can fall.”

“I always feel like I’m ready to fall.”

“You knew Chief,” she said. “Didn’t you?”

“A little.”

“Tell me about him.”

“I haven’t talked to him in four years. He wanted control. He wanted me to work for him.”

“Why didn’t you do that?”

“I have my team. He has his. He’d let me get the plane ready and then he’d kill me. For sure if he knew he could fly out of here, he’d handpick the best people in the Systems Committee, who could fix and run the machinery wherever they landed, and it wouldn’t take long for everything here to turn back to desert. That Canadian wasted our time. He didn’t want to do the work. He wanted to read the flight manuals, but reading the manuals isn’t enough. Good ideas come slowly these days, Marci. And now I have a good idea.”

She waited for the idea while he opened another small bottle of Absolut.

“I want you to go to the DMV motor pool, pretend you’re a Driftette, work for them, and wait until a pilot is verified.”

“Why me?”

“You’re good at sweeping up. You’ll be doing a lot of that.”

“For how long?”

“I don’t know. If a pilot does get verified, we have to grab him before he’s taken behind the Fence. Once Chief has a pilot, he’ll find a way to attack us and win.”

“If they attack us, we’ll just blow up the plane. Won’t we?”

“We’d like Chief to think so. But if Chief gets a pilot, he can sit with him until we run out of food. We have enough for a year, maybe a little more. The Fence has food and supplies to last twenty lifetimes, forever.”

Marci tried to feel the difference between a year and forever. “How do you know a pilot is going to get verified?”

“I don’t.”

“How will I find out working in the motor pool?”

“I can’t get you any closer to the DMV and I can’t get you into Center Camp. The DMV sends the verified to the Playa on the Christina and the driver comes from the motor pool. It’ll be news. We’ll set you up with radios and we’ll always have a team nearby.”

“I don’t know how to be a Driftette. What do I have to do?”

“The weakness of the First Wave is that they’re lazy about cleaning up after themselves and they’re always happy to let someone else sweep up around them. Be eccentric in your work and endearing in your manner. Dance a jig to music only you can hear. Make them laugh at the way you move but don’t let them see you connect the laughter to the gesture. Don’t talk more than the chattiest Drifters, and don’t be noticeably better at your work than the most competent Drifters around you and not at all better than any Second Wavers. Make yourself wanted by helping and not asking for anything. Amuse the First Wavers. Come and go at random times. Make them happy to see you again. Be their dog. Be their little puppy dog who likes to run away sometimes.”

“Do puppies run away?”

“I saw it in a movie.”

“This could take a long time.”

He pointed to the sky. “One of those lights is a space station. There are six men and a woman in there, from America and Russia. After communications stopped with Houston and Russia that first November, they watched the lights of the cities go out. They watched planes crash and boats sink, saw the fires and the oil slicks spread over oceans. They had enough food and water to last eight more months and might have starved to death but after Earth’s second silent month, one of them opened an airlock while the others were sleeping. We’re in a space station here and we have to get away. I don’t want to live in a world ruled by the First Wave.”

“How do you know it’s going to be different anywhere else?”

“Will you do the job or not, Marci?”

She didn’t answer, distracted by the dead astronauts in the tomb of the space station, forgotten by the people who put them there.

“How do you know how the astronauts died?”

“That’s a good question. That’s why you’re right for the job.”

“But how do you know they died like you say if they couldn’t talk to anyone on Earth?”

“It’s what I would have done.”

“Why did this have to wait until dark to tell me?”

“You’re a Drifter now. Drifters don’t ask questions.”

Eckmann led Marci through the minefield the next night. She went downtown first, where she slipped into the crowds of Second Wavers and Drifters who were always out until dawn, and from there walked to Hollywood and the DMV.

When the motor pool crew arrived in the morning, they saw nothing special about the quiet Driftette in the hooded parka with the fake wolf-tail trim, sweeping the sidewalk with a broom.

After ten days of this, AutoZone missed her when she disappeared and was happy to see her when she showed up again. Marci came in early each day because she liked having the company. She let Carrera teach her how to pick up the metal parts that rolled on the garage floor. She jumped from one foot to the other, attempting a broken rhythm, her idea of what she thought Eckmann meant by a jig.

So it was on the ninety-eighth day, by Marci’s markings—not by what was strictly accurate—that Seth Kaplan was verified. AutoZone took the call from Erin. “Fire up the Christina. They just verified a doctor.”

“It’s my turn,” said Carrera, grabbing the white cap with the braided gold anchors above the black brim. He put on the admiral’s jacket from the Paramount costume department.