Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

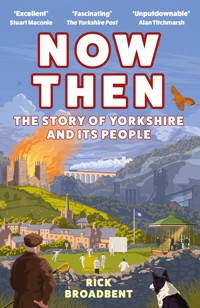

'An enlightening, enjoyable and frequently very funny journey into what makes Yorkshire stand out from the crowd ... a fascinating insight into our wonderful region and the people that make it what it is.' The Yorkshire Post Written from the perspective of an exiled Yorkshireman this bestselling, award-winning author returns to his native county to discover and reveal its soul. We all know the tropes - Geoffrey Boycott incarnate, ferret-leggers and folk singers gambolling about Ilkley Moor without appropriate headgear - but why is Yorkshire God's Own County? Exiled Yorkshireman Rick Broadbent sets out to find out whether Yorkshireness is something that can be summed up and whether it even matters in a shrinking world. Along the way he meets rock stars, ramblers and rhubarb growers as he searches for answers and a decent cup of tea. Now Then is a biographical mosaic of a place that has been victimised and stereotyped since the days of William the Conqueror. Incorporating social history, memoir and author interviews, Now Then is not a hagiography. Broadbent visits the scenes of industrial neglect and forgotten tragedy, as well as examining the truth about well-known Yorkshire figures and institutions. Featuring Kes, the Sheffield Outrages and the most controversial poem ever written, as well as a heroic dog, a lost albatross and a stuffed crocodile, Now Then is an affectionate but unsparing look at a county, its inhabitants and their flinty vowels. This is a funny, wise and searching account of a place that claims to have given the world its first football club and England its last witch-burning. It does include cobbles, trumpets and stiff-necked, wilful obstinacy, but it is also about ordinary Yorkshire and its extraordinary lives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 660

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘An enlightening, enjoyable and frequently very funny journey into what makes Yorkshire stand out from the crowd.’ Yorkshire Post

‘If you wish to know what social, cultural and historical erosions shaped the land we live on – a behind-the-scenes view of “God’s Own Country” – then look no further than Now Then.’ The Dalesman

‘A humorously honest, unsparing, celebratory biographical mosaic, not a hagiography. [...] Social history, memoir and reportage, high hills and flat vowels are woven into the mosaic of Yorkshire now and Yorkshire then, ordinary Yorkshire and its extraordinary lives.’ The Press

*

‘From Yorkshire? Who do you think you are? Cut through the cliches and seek the truth with Now Then. Not from Yorkshire? Commiserations, but you can still enjoy some vicarious greatness by reading Rick’s book.’ Tom Palmer, author of After the War and winner of the Ruth Rendell Award

‘Quite unputdownable. In Now Then, Rick Broadbent has encapsulated the spirit of the folk and the mood of the places so perfectly. I was hooked from page one. Prodigiously researched with wit woven into the narrative, it recreates the raw atmosphere of the place that made me. Anyone born in the county should read it. It will help them understand just what they were born into.’ Alan Titchmarsh

‘As a Lancastrian, I should try and tell you that this is a terrible book. But it is not. A passionate but clear-eyed evocation of the “Texas” of England that avoids “God’s Own Country” blather but is broad and rich enough to include Ted Hughes and Jarvis Cocker as well as Orgreave and Hillsborough. Excellent.’ Stuart Maconie

Also by Rick Broadbent:

Looking for Eric: in search of the Leeds Greats

The Big If: the life and death of Johnny Owen

Ring of Fire

That Near-Death Thing

Endurance: the extraordinary life and times of Emil Zatopek

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Allen & Unwin,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin.

Copyright © Rick Broadbent, 2023

The moral right of Rick Broadbent to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Thanks to the following for kindly allowing their work to be used in this book:

V, by Tony Harrison, copyright Tony Harrison, published by

Bloodaxe Books (1985–1989)

‘Highroyds’, from the album Yours Truly, Angry Mob, by Kaiser Chiefs, written by White, Baines, Hodgson, Wilson and Rix, published by Concord Songs Limited

Division Street by Helen Mort, published by Chatto & Windus.

Copyright © Helen Mort, 2013. Reprinted by permission of

The Random House Group Limited.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 737 7

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my brilliant mum

CONTENTS

Prologue: Digging Up the Past

1 Outsiders

2 Workers

3 Writers

4 Miners

5 Minstrels

6 Artists

7 Yorkists

8 Stereotykes

9 Champions

10 Ramblers

11 Chefs

12 Pioneers

13 Legends

14 Seasiders

15 Now

16 Then

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Prologue:

DIGGING UP THE PAST

‘Do you want it all?’

One thing to remember when exhuming the ashes of parents is to always take your own casket. Not having done this sort of thing before, Mum and I had arrived unarmed at the black iron gates of Tadcaster Cemetery, squeezed into a triangular plot of weary grass between a graffitied wall and the road to the breweries.

The original casket had long since rotted away. The cemetery man sighed, walked into his sooty black office and emerged with a cloudy coffee jar. My dad had put on some weight in the last few years of his life, and I could not help wondering whether it would be big enough.

‘Well, as much as you can manage,’ I answered, and after removing the stone tablet and some turf, he started scooping up mud and worms.

It was 2011, 25 years since my dad had died of a heart operation gone wrong, and it was time to move him. His sons had all gone south through work and love and gravity. Now Mum had gone too, so it seemed wrong to leave him there in Yorkshire beneath a slab of unseen stone, growing ever smaller in tandem with the cemetery man’s to-do list. He had always wanted to end up in Cornwall, the venue for what felt like all our family holidays, several hundred miles away. I was sure he’d miss things like the Angel in Tadcaster, even if I remember it as a barren pub tinted grubby brown. Whatever time of day you went in, there would be the same faces with personalised tankards and personalised seats, taking it personally. It was like the scene in An American Werewolf in London, in which overseas visitors walk into another Yorkshire pub, and Brian Glover, that gruffly affable wrestler-turned-actor, throws a bad dart and growls, ‘You made me miss.’ It was great.

‘Do you want the stone as well?’

Mum and I exchanged puzzled looks. We had not anticipated taking the tablet that covered what, as it turned out, was not his final resting place. ‘Well, yes,’ she said. I nodded. Then I contemplated picking the thing up.

‘’Evee, in’t it?’ Cemetery Man said.

‘Yes. Slippy too.’

‘’Ang on.’

He went back into his office and emerged with a Tesco carrier bag, which he wrapped around the corners so it looked like we had a huge pizza. I lifted it and staggered to Mum’s old Honda Civic, the rust blossoming in the rain. I let it drop into the boot, and the suspension roared with the pain of a wrestler flattened from the top rope.

‘Don’t forget this,’ Cemetery Man said, and handed me the coffee jar.

‘Thanks.’

‘Better go. I’ve got an eleven o’clock.’ He sounded like a businessman rather than a man who mowed the lawn and sometimes cut back the long bits. He lived on the edges. He was the man who tended borders. Grumpily. He seemed the perfect fit.

From that moment I started to think about the Yorkshire we had known. It felt like a severing of roots, and leaving again made me reconsider. I loved the place but had sometimes loathed it too. Now its uniqueness hit as hard as a Leeds United hooligan behind the Lowfields Road terrace in the 1980s. All points mattered – north was the posh bit with people who ate game, wore tweed and went to Ripon races of an afternoon; west was the land of mills and honey, an industrial landscape leavened by David Hockney and his paintings of naked Californians; south was steel and Sheffield and Jarvis Cocker wiggling his bum at Michael Jackson; east had gone west long ago, leaving an aftershock that would come to be known as Humberside, and then the East Riding of Yorkshire, or something.

Not long afterwards, we stood in a West Cornwall car park by Lamorna Cove at the wits’ end of England. I thought back to nights at home, in the Falcon where my best friend lived and painted Monet’s Poppy Fields near Argenteuil on his bedroom wall; to John Smith’s, a bag of scraps, vinegar on cut lips, dodging quarry lorries, Ilkley Moor, light and shade, life and death, Dad then and Dad now. We opened the coffee jar at the end of the Cornish valley and chalked our names on a rock that we would forget in the years to come. Mum added a shot of whisky for the journey. I took my dad in hand again, but the ashes were damp and heavy, and almost decapitated the seagulls below us. This curious substance plummeted like a brick, but we at least scattered the scavengers. And though we were now bound to this other place, it was at that moment that I pondered whether, in this life or the next, you ever really leave Yorkshire.

I recalled that distinctive greeting when you met friends: ‘Now then.’

That summed it up. The past and present bottled in a dirty jar. Yorkshire – there is no better place.

But …

More years passed, and I became older than my dad had ever been. My kids were now older than I was when he died; 51 and 17 were the numbers. That sort of stuff makes you think. The cemetery stone is down the bottom of our Dorset garden. A Very Special Man. Mum and Dad always wrote ‘ILA’ on their Christmas and birthday cards, and while it could have stood for Interstitial Lung Abnormality or the Idaho Lacrosse Association, I guessed it was I and Love and Always. Or close. But I never asked. In another year I would have lived in Dorset for 19 years, as long as I managed in Yorkshire before going to see what the south was all about at a university that didn’t bother with interviews. I decided I had to go and look again. As my dad became ever more distant, I wanted to go back and find out what had helped make him what he was, and what made Yorkshire a place that had been victimised and stereotyped since the days of William the Conqueror and beyond.

We all know the tropes – Geoffrey Boycott incarnate, whippets, flat caps and fat heads, folk singers gambolling about Ilkley Moor without appropriate headgear – but why is this God’s Own Country? After all, Sutherland Shire in Australia and Kerala in India have also claimed the mantle, while the Nazis published propaganda taking issue with the USA using the term in the 1940s. In England, one origin story has Jesus visiting with his great-uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, who was there to buy Cornish tin; this version also has Jesus as a model for the legend of King Arthur, so perhaps Cornwall is God’s Own Country. Or County. Which is it, anyway?

A few other questions buzzed. Why, now that our family had left for good, did I feel the pull to return? And can you ascribe communal characteristics to a place that has a bigger economy than Wales, more people than Scotland, and includes three of the UK’s largest cities? Can you distil some sort of familial traits from the creative breadth of a region that spawned TV programmes as diverse as All Creatures Great and Small and All Creatures Great and Small the remake? I’m joking. I know it’s wrong to stereotype Yorkshire folk as tough-talking tykes with an unreconstructed view of the world, and I know that at least some of my old friends have long been aware that Les Misérables is not a dour northern comic. But I wanted to scrape away this scabbing and find out the raw history of a place that claimed to have given the world its first football club and England its last witch-burning. I wanted to know if Yorkshireness was even a thing any more, and whether that mattered in a shrinking world; and I also thought that, just maybe, if I went backwards, I might feel closer to my dad.

Bill Bryson started his book about going home to America, The Lost Continent, with the line: ‘I come from Des Moines. Someone had to.’ But I have always sensed that exiled Yorkshire folk’s pride in the Knaresborough Bed Race grows in direct proportion to the likelihood of them never having to attend it. So I decided to bin the rose-tinted binoculars and regress, to look at Yorkshire past and present. Basically, I wanted to know if we had made a mistake by chucking Dad off the Cornish coast.

As Yorkshire is so large, multifarious and unmanageable, I decided to break down this account into sections. Inevitably, themes and characters run from one chapter to another like geological seams, but I decided this was my best chance to get a grip on an unwieldly past rather than trying to cover everything chronologically. I apologise for the many missed-out bits. History is a selective edit, and this is a personal attempt to separate myth from massaged memory and reality from perfumed legend. I hope that by weaving these strands together, some sort of tapestry will emerge, even if, come the final reckoning, it does not say ‘Home Sweet Home’.

It was a journey of rediscovery that I tried to make with a broad brush and broader mind. Some of the things I would learn about, revisit and revise included the Sheffield Outrages, Wuthering Heights, the fire at York Minster, the miners’ strike, Ted and Sylvia, Kaiser Chiefs, the Yorkshire accent, Kes, republicanism, Davids Batty, Bowie and Hockney, wool and Wilberforce, the tragedy of sport, the ‘Four Yorkshiremen’ sketch, the M1, M&S, ferret legging, the Ridings row, the most controversial poem ever written, and bitter. Lots and lots of bitter.

1

OUTSIDERS

We just thought people in Yorkshire hated everyone else, we didn’t realise they hated each other so much.

David Cameron, prime minister, 2014

In 2021, the Yorkshire Society issued a report into the future of the region. The survey answers were to be expected: people overwhelmingly saw themselves as from Yorkshire, not England; twice as many respondents would vote for a Yorkshire parliament than against it; a quarter said, yes, they could see Yorkshire being an independent country. Part of this is down to a superiority complex and part to the scars and suspicion of outsiders, southrons and offcumdens. Yorkshire welcomes you with terms and conditions and an understanding that just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not coming for you.

Aliens and zombies

Before heading back to Tadcaster, the brewery town set between Leeds and York where I grew up (someone had to), I dug around in some archives. I came across one story that seemed to sum up the perceptions that outsiders have of Yorkshire, namely that people there are suspicious of them. It was the spring of 2012, and as the rest of Britain was warming up for the Olympic Games in a southern city called London, a town councillor in the Stakesby ward of Whitby went the extra mile to prove that people from Yorkshire were, as many had long suspected, different.

Tradition dictated that denizens of Yorkshire were mean, blunt and marinated in beef dripping, but Simon Parkes felt the other-worldliness went deeper, even past the perennial calls to turn the nation’s largest county into a republic. Councillor Parkes maintained that he had been adopted by a nine-foot-tall green alien and had been for a life-altering spin in her spaceship when he was only eleven. He elaborated in a series of internet videos, but had grown weary of explaining himself by the time the national media got wind of the tale. ‘It’s a personal matter and doesn’t affect my work,’ he told the Guardian. ‘People don’t want to talk to me about aliens and I’m more interested in fixing someone’s leaking roof or potholes.’ The mayor of Whitby said he was ‘completely in the dark’, but added generously that everyone was entitled to a private life. Effortlessly shifting perspective, Councillor Parkes then gained the support of Whitby’s townsfolk by turning his extraterrestrial parenthood into a parochial issue. ‘I get more sense out of the aliens than out of Scarborough Town Hall.’

Of course, as everyone in Whitby, Scarborough and the wider Wolds knows, everyone’s a bit funny when you get past Woodall Services, but it was an undeniably fresh take on the status of the outsider. This distrust is an age-old fact rather than fantasy, and if you get a few minutes, I heartily recommend looking through the Tripadvisor reviews for Wharram Percy, a deserted medieval village between York and Scarborough, and drink in the disillusionment you will find: ‘The angry farmer that lives next door decided to come out and scare us off by shooting his shotgun in the air for some unknown reason. I won’t be visiting again unless I have a police escort and a decent bulletproof vest. Can only recommend this place to someone who either doesn’t care about their life or would like to commit suicide. It’s a no from me.’ Or: ‘There was a boarded-up farmhouse and the remains of a church but not very much more to be seen. Disappointing couple of hours. Won’t be back.’ A more optimistic poster suggests: ‘May be of interest to aficionados of cross-country hikes and lumpy meadows.’ But the gist is undeniable, and the bottom line comes from the definitively blunt subject heading of another review: ‘You can see why it’s deserted’.

Why it is deserted has been a long source of debate. What we know for sure is that by 1086, William the Conqueror had confiscated Wharram, and the Percy family, best known for the less controversial village of Bolton Percy, near York, came to control the settlement, lumpy meadows and all. Southerners paid little attention until the 1960s, when an archaeological dig unearthed 137 human bones. This was a good haul by any digger’s standards, but those archaeologists must have been a slightly apathetic bunch, as it was not until 2017 that a team from Historic England and the University of Southampton looked closer and an ugly truth emerged. The bones were not just graveyard relics but had also been burnt and mutilated with axes, swords and knives. It was deduced that this had been an attempt to stop the corpses rising and wreaking havoc on the good, if undeniably violent, folk of Wharram Percy. Lingering malevolent life forces in individuals who had committed evil deeds when properly alive was big back then, when the preferred way of dealing with a revenant – or zombie, in modern parlance – was simply to dig up the corpse, dismember it and then have a good old sing-song round the campfire.

In his twelfth-century hit Life and Miracles of St Modwenna, Geoffrey of Burton insisted this behaviour was commonplace. He wrote of two men rising from the grave in another village and, despite the not inconsiderable burden of having coffins on their backs, proceeding to terrorise villagers, who developed a tendency to be found dead the following morning. This was before Agatha Christie, and so the villagers did what any decent medieval person would do and, ignoring parish council protocols, started to rip out the hearts of the undead. Severed heads were placed between the legs of the corpses in a final act of indignity, although in hindsight it was generally accepted that dignity was probably not at the forefront of a zombie’s warped mind.

I had visited Wharram Percy a couple of years before deciding to write this book, and could not help but think that Historic England had not played on this in the same way that the more mercenary entrepreneur might. There is no zombie gift shop, no black or blue plaques, not even a café selling headless beer. In fact, there is no evidence of the walking dead at all. It is basically a field exercise. Perhaps Historic England deserves credit for this. History owes as much to imagination as to fact, and if you sit in the lumpy meadow between the lake and the cemetery, it is not hard to envisage a dark night and some flaming pitchforks.

Many people will recognise that Yorkshire. For them it is a small-minded place, like one of those interview rooms in the detective programmes where you can see in but they can’t see out, and no doubt these critics would warm to another theory, namely that the mutilations were down to a fear not of revenants, but outsiders. This seemed plausible to me, but Alistair Pike, professor in Archaeological Science at the University of Southampton, dismissed the idea. ‘Strontium isotopes in teeth reflect the geology on which an individual was living as their teeth formed in childhood,’ he began in an assessment in the Yorkshire Post. ‘A match between the isotopes in the teeth and the geology around Wharram Percy suggests they grew up in an area close to where they were buried, possibly in the village.’ The professor did admit that this had caught his team of isotope testers off guard; they had feared this was Yorkshire, imbued with the spirit of Brian Glover, baring its teeth to newcomers. ‘This was surprising to us as we first wondered if the unusual treatment of the bodies might relate to them being from further afield rather than local.’

We know the village was deserted not long after 1636. Skeletal scientists, archaeologists and historians wondered if it was down to this ghoulish past, or perhaps the Black Death. Eventually they deduced it was sheep. In the post-medieval period, common land was closed off by walls and ditches, and the price of wool meant landowners turned away from arable farming. Across Britain, settlements succumbed to depopulation, and families who had lived by the plough were rendered useless. They left, and for the living, the dead and the disgruntled of Tripadvisor, there would be no coming back.

Who do you think you are?

2 November 2022 is a historic date, and I take a drive over to Langton Matravers, near Swanage in Dorset. This small village is set in the heart of the Purbeck Hills. You could easily call it God’s Own Country. Here today is where the three norths will meet for the first time over Britain. Three norths? you ask. Well, yes. There is true north, which is the direction of the lines of longitude that go to the North Pole. Grid north caters to cartography and nods to the fact that maps are flat representations of a curved surface. These norths merge two degrees west of Greenwich. Then there is magnetic north, which is where your compass points, though unhelpfully it changes due to variations in the earth’s magnetic field. Indeed, it has been moving up to 30 miles a year, according to the British Geological Survey. Leeds University scientists have also found that two competing magnetic blobs on the earth’s outer core have caused magnetic north to move from Canada to Siberia. Now, for the first time in British mapping history, the three norths have chosen Langton Matravers as their meeting place. This sounds confusing. The most northern place in Britain today is just off the South West Coast Path. The one man I see as I reach the village sounds equally confused when I ask if he’s here for the three norths. ‘No,’ he says. ‘I’m waiting for the boilerman.’

If the north is confusing as a single entity, Yorkshireness can be just as baffling. Is it a thing, and if so, what? In 2016, researchers from the Ancestry genealogy website said they had analysed the genetic history of two million people and concluded that Yorkshire had the highest percentage of Anglo-Saxon ancestry (41.7 per cent) in the UK. This translated into headlines about Yorkshire folk being the most ‘British’ people going. Whether you saw this as cause for celebration may have depended on how you felt about Anglo-Saxon pursuits such as wrecking French market squares before kick-off and empathy levels for migrants risking their lives in overcrowded Channel dinghies.

The Angles came from Angeln in northern Germany. The Saxons were Germanic coastal raiders. So who do we think we are? Well, the Neanderthals made it back to Britain via the Doggerland – a land mass connecting Britain to Europe, and not what you think – but the weather meant it was sporadically occupied. Indeed, given there was a catastrophic Ice Age, modern Britons can all be regarded as immigrants, with the first people to travel north being reindeer chasers, as suggested by 12,000-year-old cave art across the border at Cresswell Crags in Derbyshire. DNA testing enabled researchers such as Alistair Moffat, of Yorkshire’s DNA project, to study Y chromosome lineages passed from fathers to sons. He found Yorkshire people were, indeed, different. The most common chromosome lineage across Britain was officially R1b-S145, which the researchers called Pretani, a derivative of a Greek word meaning ‘tattooed people’. The Ancient Britons were Celts and were around during the Iron Age, which started around 800 bc. Their origin story has been disputed, but one theory is they may have originated in France. Moffat said this Pretani lineage was present in a third of British males, but in Yorkshire the figure was much smaller; according to Moffat, more than half of its Y chromosome came from groups he labelled Germanic, Teutonic, Saxon, Alpine, Scandinavian and Norse Viking. This compared with 28 per cent across the rump of Britain. Basically, Yorkshire people were actually more western European and southern Scandinavian than the rest of the UK.

Back in 2007, an article in the European Journal of Human Genetics offered more pause for thought. A team from Leicester University had found the hgA1 chromosome in an ‘indigenous’ British male, which suggested a west African origin. The researchers said seven out of eighteen men carrying what they called ‘the same rare East Yorkshire surname’ had the hgA1 chromosome. ‘Our findings represent the first genetic evidence of Africans among “indigenous” British, and emphasise the complexity of human migration history,’ they wrote.

The researchers did not name the men, but the Mail on Sunday found one. He was John Revis, 75, a retired surveyor living in Leicester. He had responded to a newspaper advertisement looking for people who had researched their own ancestry and would be willing to give DNA samples. He said he was flabbergasted, and friends at his bowls club were shocked. ‘At least now they can say they have got one more ethnic-minority member,’ he said.

An African presence in Yorkshire was not a new concept, even if the genetic trace was. In 1901, a skeleton was found in Sycamore Terrace in York on the site of an old cemetery. It was clear that the woman, aged around 20, was of some social standing, due to the jet and ivory bangles and the glass necklace and earrings found with her. She became known as the Ivory Bangle Lady, a woman of Roman Britain, but it took until 2017 for her origins to be more scrupulously addressed. By measuring chemical markers in her bones and teeth, Dr Hella Eckardt’s team at Reading University deduced that the Ivory Bangle Lady was of mixed heritage and partly North African descent. This was significant, as it went against the idea that slavery alone was responsible for the first black people in Britain. Some found this curiously hard to take, and the Yorkshire Museum faced a vitriolic backlash for stating as much in a blog. It responded: ‘Let’s be clear, Roman Britain and Roman York were diverse places with people from all over the empire mixing together. Romans were not all white, male soldiers. Anyone who suggests otherwise is factually incorrect.’ They might have added that Septimius Severus, one of York’s Roman emperors, was Libyan.

However, one of the Leicester researchers thought the most likely cause of the Revis African lineage in East Yorkshire was the slave trade. Slavery was abolished in most of the British Empire in 1833, but that did not stop it elsewhere, or the victimisation of those who looked different. In 1904, the Bradford Exhibition, designed to champion the textile industry, featured a village in which spectators were invited to gawk at 100 Somalis and their chief as they threw spears and shot arrows. More than two million people came to watch. A team of Somali children defeated a local ladies’ cricket team, and the chief’s newly born daughter was named Hadija Yorkshire. Such human zoos were common at the end of the nineteenth century, but some people were less able to cope when black and Asian people settled and did not move on.

There were riots in 1919 as the immigrant population became the spittoon for anger over a lack of post-war jobs and housing. The arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948 brought people from the West Indies who filled the gap in the labour market and helped to rebuild Britain. Boats from Africa also arrived, although mass immigration was a thing of the fifties. South Asian migrants also moved to the UK, with many settling in West Yorkshire, but they too suffered as industrial problems were turned against them.

In 1981, the racial tension boiled over and riots broke out around the UK. In Chapeltown in Leeds, much of the focus was on the damage and mayhem rather than the causes. ‘Inside the trouble areas coloured youths were seen touring around in cars,’ said the Yorkshire Evening Post. ‘Police believe CB radios were being used to help the rioters slip the police net.’ Leeds Other Paper was more sympathetic. It told of how in the preamble to the riots, three white youths attacked a black youth in broad daylight; of white women working in a ‘black-owned chip shop’ being called ‘n*****-loving bitches’; of a gang of skinheads singing racist slogans.

There were riots in West Yorkshire, notably in Bradford, in the 1990s, and then the devastation of 2001, when more than 1,000 young people clashed with police. Tension had already been high across the north, but the juxtaposition of a gathering of the National Front and an Anti-Nazi League rally in Centenary Square ended violently. Estimates of the damage published in the media ranged from £7 million to £27 million. An inquiry by Lord Ouseley, former head of the Commission for Racial Equality, was conducted before the riot; the report, published afterwards, painted a picture of segregated communities, and said that neither all-white nor all-Muslim schools did enough to preach understanding.

Bradford’s reputation was the collateral damage, but that was a minor thing compared with the fault lines caused by housing, education, drugs and discrimination. As had been the case with race riots 20 years earlier, deep despondency and distrust of civic leaders were raging undercurrents. Bradford, where my family hails from, is now one of the most deprived areas in Britain, with half the children in Bradford East and West living in poverty between 2015 and 2019. That’s half. It is clear Yorkshire has still got serious problems.

It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at

So said Sheffield singer Richard Hawley at a gig in Leicester in 2007, after a few people in the audience roared with delight when he name-checked his home city. He had a point, but to understand modern Yorkshire – a place that both Bill Bryson and England football manager Gareth Southgate chose to make their home despite being from Des Moines and Watford respectively – you do need to know where it came from. Yes, it was a lump of ancient volcanic rock, once a desert, then an icy wasteland, and yes, it drifted up from Spain with the rest of Britain, which is ironic really, now that Britain goes back to Spain every summer to celebrate sunburn and the olden days. There is a Mesolithic site at Star Carr, a few miles from Scarborough, and Neolithic burial mounds to the east in the Wolds, but the heady depths of Yorkshire archaeology came in the 1830s, when a man called Michael Horner lost his dog in a cave at Langcliffe Scar, high above Settle in the Yorkshire Dales. He crawled into a hole in search of the missing canine and found bones and coins and a variety of man-made objects. Not knowing the history of Wharram Percy, he was not in the least fazed by this. The place was soon subject to intense excavation, with the artefacts found including the fossilised bones of hippos and elephants, dating back some 130,000 years to a time before tanning booths. It would even grab the attention of Charles Darwin, who helped set up the Settle Cave Exploration Committee, and if by the 1890s geologists were squabbling over finds, with one, James Geikie, calling another, William Boyd Dawkins, a ‘nincompoop’, Victoria Cave helped our understanding of the creation of Yorkshire.

Other finds have suggested that what would become Yorkshire was first inhabited by people around 9000 bc. Tools were found that showed these first Yorkshiremen and women were hunter-gatherers, fishers and farmers. If we can trust these treasures, they seemed particularly keen on making flint harpoons and preserving fish scales.

Then, in 2017, an Iron Age chariot and horse skeleton were found in a field in Pocklington, some 12 miles to the east of York. This news was of particular interest to me, as in the mid 1980s, when I was 19, I had spent a year working on a two-man newspaper called the Pocklington Post. The news agenda had been so limited that a golden wedding could be guaranteed to make the front page; an Iron Age chariot was off the scale. I feel sure we would have given it an extra column.

Nowadays, Yorkshire – or more accurately that little slice of misplaced Surrey called York – is synonymous with the Romans. It was part of their empire from ad 71 to around 410, but prior to that, the Brigantes had lived peacefully enough under their queen, Cartimandua. After the Roman invasions of ad 43, she seemed to be behaving diplomatically enough, although this has alternatively been interpreted as devious treachery. Certainly, in handing over the British resistance leader, Caratacus, to the Romans, she ensured favour from Rome but revulsion from others.

However, it was when she divorced her husband, Venutius, and took up with a mere servant, Vellocatus, that her fortunes really turned. There are no known Brigantes historians, so it was left to the Roman scribe Tacitus to provide a skewed version of events. He claimed the royal house was ‘shaken by this disgraceful act’. In addition, Cartimandua had used ‘cunning stratagems’ to capture her ex-husband’s kinfolk, and people were ‘stung with shame at the prospect of falling under the dominion of a woman’. Yorkshire’s warrior queen was no Boadicea.

A domestic issue grew into wholesale battle that was settled only when the Romans sent their crack fighting force, the IX Hispana, to help the queen. The upshot was the Romans were now in Yorkshire and found it to their liking. When Venutius revolted again in around ad 69, the Romans were distracted by other troublemakers, and Cartimandua was evacuated to Chester. The great queen of the north then disappears from history, although it is believed she had a fortress at Stanwick St John, way up north to the west of Darlington. Shortly afterwards, the IX Hispana conquered the Brigantes and built a wooden fortress that they set about turning into the tourist attraction of Eboracum. ‘Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, scorn all others,’ said Emperor Severus on his deathbed. Many in Yorkshire still abide by part of this sentiment.

Eventually the Romans got bored and went off to start wars and introduce better healthcare to other corners of the Empire, so that by the end of the fifth century, the Angles got their chance to have a go. York then became the capital of Eoforwic and Edwin of Northumbria stretched his wings to conquer Elmet, which included the prized assets of what would become Leeds and Hallamshire. Then came the Vikings and Ragnar Lodbrok, sometimes known as Raggy Shaggy Breeches, who tried to introduce conscription in Northumbria and, according to legend, was duly tossed into a snake pit for his trouble.

Undeterred, the Vikings renamed York as Jorvik, thus paving the way for mass queues for the eponymous centre, which opened in 1984 to considerable fanfare, with articles in the national media and rave reviews about how even the smell of manure was authentic. With no way to verify the truth of this, the imagined whiff of Viking dung lingered over many a dinner party in the Georgian town houses of Bootham in the late eighties.

The history of Yorkshire is one of blow-ins, or ‘offcumdens’, of migration and ensuing conflict. The creation of the county as a single entity can be attributed to the Vikings, too, with their three ridings. A riding was a thirding, and so there was North, West and East but no South, although Winifred Holtby did write a compensatory novel, South Riding, in the 1930s. The ridings lasted until 1974, when the Local Government Act played more havoc with identities. Parts of the North Riding, including Middlesbrough, were now in Cleveland, others in County Durham. Hull and Goole went to Humberside, Sedbergh to Cumbria. People went mad.

The Danish influence endured, and then in 1066, Edward the Confessor, England’s penultimate Anglo-Saxon king, died and all hell broke loose. I will get to elements of Yorkshire’s magnificently bloody history elsewhere, but suffice it to say here that King Harold (Godwinson) beat a Norwegian army, also confusingly led by a king called Harald (Hardrada), at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, just outside York. The Norman invasion was the next problem, and Stamford Bridge morphed into the Battle of Hastings, which was really the Battle of Battle, where all Hal broke loose and William the Conqueror became King of England.

The north, unsurprisingly, did not take the Norman Conquest well, and rebelled, which led to the scorched earth campaign that would become known as the Harrying of the North in 1069–70. Simeon of Durham, a monk and a scholar, damned William thus: ‘It was horrific to behold human corpses decaying in the houses, the streets and the roads, swarming with worms. For no one was left to bury them in the earth, all being cut off either by the sword or by famine. There was no village inhabited between York and Durham – they became lurking places to wild beasts and robbers.’ Domesday Book, commissioned by William lest we forget, recorded that 75 per cent of the population of the region died or fled during this period.

Orderic Vitalis, an Anglo-Norman chronicler and later a health spa on the ring road, bought this version and wrote an account decades later: ‘The King stopped at nothing to hunt his enemies. He cut down many people and destroyed homes and land. Nowhere else had he shown such cruelty. This made a real change. To his shame, William made no effort to control his fury, punishing the innocent with the guilty. He ordered crops, animals, tools and food be burnt to ashes. More than 100,000 people perished of starvation. I have often praised William in this book, but I can say nothing good about this brutal slaughter. God will punish him.’

In 2014, Rob Wright sat in a hall in York and contemplated the daunting task in front of him. The academic was midway through a lecture series intent on restoring the reputation of William the Conqueror. This rewriting of history is an important cornerstone of progress, but as he looked out at the audience, he must have known he was up against it. After all, others claimed that William’s Harrying of the North could reasonably be classed as genocide. Dr Wright took a deep breath and argued that William would not have had enough men to cause the carnage he had long been accused of. ‘William did crush a rebellion with force, but we shouldn’t forget what the Normans did for us,’ he opined. This sailed dangerously close to Monty Python asking what the Romans had done for us too, but Dr Wright pressed on. ‘Not least bringing the culture of Christianity to our shores.’

A few abbeys were scant compensation for some, and by the end of his series, Dr Wright concluded that he was unsure whether he had managed to change any minds. ‘It’s hard to make people listen,’ he admitted. ‘I guess a villainous reputation with all its blood and gore is much more interesting than the truth.’

Sócrates’ shin pads

Reputation can be both carved in stone and a fragile thing, but the Harrying of the North is scarcely the sort of historical tale that would foster a love of outsiders. Ancient tales can become passed-on truisms over decades and then centuries, and it is possible to develop a perverse pride in old prejudices.

Not long after deciding to write this book, I went to see Simon Clifford, a maverick and eccentric Yorkshireman who made a million from creating Brazilian Soccer Schools in a flat above an Italian café opposite where my father used to work in Briggate, in Leeds city centre. Simon was middle-aged now but looked younger. He had long, well-kept hair and gave short shrift to anyone who thought small. Prince William had called him ‘tenacious’ and ‘a force of nature’. He seemed to know everyone and had eclectic tastes. In his garage you could find Luke Skywalker’s original landspeeder and football manager Brian Clough’s old desk. Simon also did the football choreography for films such as Bend It Like Beckham, The Damned United and The English Game. When his Brazilian soccer schools were gaining success at the turn of the century, he asked Lego for £20,000 sponsorship and they gave him £2 million. His story is remarkable by anyone’s standards.

A former primary school teacher, he began coaching waifs and strays at a school snubbed by society. ‘I sat them down and made them watch a film about the great Brazilian players. I said, “This is Pelé, this is Zico and this is how we’re going to play. We start Thursday.”’

He became renowned, and mocked, for focusing on tricks and skills, but eventually got a job at Premier League club Southampton. Then he bought his own club, Garforth Town, in the eleventh tier of English football – whose ground was round the back of the dentist’s where a man with a drill and dense nasal hair had terrorised me as a youth – and said he would take them into the Premier League with his methods. He was good at speaking about Yorkshire and how what he had done could not have happened anywhere else. ‘People here are open-minded,’ he said. ‘They accept anyone as long as they work hard.’

‘They all thought you were mad, though, didn’t they?’

‘Yes, but I was mad,’ he said. He was all passion. ‘I was like Rambo, I never drew first blood, but if you underestimated me then I would take you on – whatever the odds.’

I had known Simon since 2004, when he pulled off quite the coup by bringing Sócrates, one of the world’s greatest footballers and former captain of the Brazilian national team, to Yorkshire to play a cameo role for Garforth Town. I watched that match with split loyalties, as I was in awe of Sócrates’ way of playing – elegant, erudite, hairy – but I had also once played for that day’s opponents, Tadcaster Albion. I could not help thinking that it was a long way to come for five touches and thirteen minutes, and as he witnessed the heated touchline exchanges, the plummeting temperatures and the frenetic pace, Sócrates must have wondered what he had let himself in for.

He put on a philosophical front after his debut in the Northern Counties East top-of-the-table clash. ‘The point is not to be playing football,’ the 50-year-old Brazilian legend said. ‘The point is Simon’s project and I’ve fallen in love with it.’ It was surreal. Leader of the globally loved 1982 side dubbed ‘the beautiful team’, Sócrates was a doctor-thinker who would write ‘Democracia’ on his golden shirt. He added that he would happily sit out next weekend’s home date with Pontefract Collieries. ‘The last time I played was so long ago I can’t even remember,’ he told me. Given that his cameo appearance raised the question of whether hyperventilation or hypothermia would get him first, his decision was understandable.

What could Yorkshire glean from Brazil?

‘Creativity and the joy of playing,’ he said as the Tadcaster manager shouted, ‘Fucking hell, ref!’ The heavily tattooed boss was clearly not enjoying the spectacle. This was brass-tacks football and Sócrates’ presence was in danger of bringing the game into repute. None of those present could get used to seeing an all-time international great sipping coffee while wearing three coats, two pairs of gloves, a hat and a scarf. ‘It’s years and years since I saw snow,’ Sócrates mused. These days football was just an interest – he busied himself with postgraduate studies and writing plays – but Simon said he would have made him take a second-half penalty had they not misplaced his shin pads and been forced to delay his substitution. The match ended in a draw.

I admired Simon. He had gatecrashed various worlds from football to film, brandishing psychedelic ideas, and was often regarded as an outsider. As I returned to Yorkshire and met him again, it felt nostalgic walking back past the café where he had once told me his plans to conquer the world. I looked across the pedestrianised street to the first-floor window where my dad had realised a more ordinary ambition. His accountancy office was now a Pilates and waxing studio. Dad was gone. Simon was still here. Yes, he had sold Brazil to the world from a cheap Briggate garret, but I wondered whether he could have done the same with Yorkshire.

2

WORKERS

There are mates of mine in Sheffield who think I’m a big ponce, but that’s because of the acting I do, not because I live in London.

Sean Bean, actor, Daily Mirror, 2008

Industry has been one of the cornerstones of Yorkshire’s reputation. From the textile mills of the west to the steel and iron manufacturing in the south, the fishing and shipbuilding industries way out east and the coal fields straddling boundaries, the great communal trades have fuelled, fed and clad a nation. A source of pride and self-image, their postwar demise cut slashing wounds as part of the county died, never to be replaced by anything as meaningful.

The beer talking

An old school friend has posted a pre-Christmas message on Facebook. ‘Would Tadcaster West revellers please refrain from pissing on the John Smith’s baby Jesus on their way home this evening.’ It is a quick reminder that Yorkshire is not immune to problems encountered in most other counties (although obviously not Dorset, which still dominates National Trust calendars and where people with thatched cottages most certainly have a portable ceramic chamber pot to piss in).

I grew up in a village called Stutton, just outside Tadcaster. There was a plot of grass across the road that was the scene of endless summer nights playing sticks, football and torchlight tig. A woman called Fag Ash Lil (it may not have been her real name) would periodically appear with a curled lip rippling beneath curlers in grey hair. If a ball landed in her flower bed, she would confiscate it and take it into her witch’s lair, where we assumed she was boiling naïve centre-backs while she made tea for the Child Catcher. The assorted players would look furtively to the floor, searching for the last vestiges of bravado, and hope they would not have to go and knock on the door.

‘Whatcha go and do that fo, Woody?’

‘I din’t mean to, did ah.’

‘You menk.’

There was a rusting signpost outside our house that stated it was 14 miles to Leeds but only 13½ to York. This geographical nugget was buried by many in the village. York was okay for nice cafés and a sizeable scone called a fat rascal, and it had a modicum of class and culture. Leeds had grime and the Leeds United footballer Billy Bremner, but it felt more quintessentially Yorkshire, even if Bremner was from Scotland, and more suited to those growing up a short walk down a disused rail track from Tadcaster, a proud working town built on beer and one which, according to Facebook, is still spilling it.

The story of the Tadcaster breweries is old and angry. This is part of a proud tradition, or more accurately, a tradition of pride. The monks of Yorkshire were big brewers and drinkers until Henry VIII suppressed the monasteries in the sixteenth century. After the dissolute gave way to dissolution, Yorkshire remained a brewing stronghold, but trouble lurked at the bottom of the barrel. Take Masham, a pretty market town on the edge of the Dales that was invaded by Vikings who, when not burning the place to the ground, introduced sheep farming to the region. This bit is usually skirted over in the more bloodthirsty dramatisations. In the nineteenth century, Robert Theakston was a farmer-turnedpub-landlord. His son would build a brewery in Paradise Fields. It thrived and eventually was subject to a series of takeovers, but disgruntled family member Paul Theakston quit and set up next door. This became the Black Sheep Brewery, because that was what he was.

The family feud that most interested me was closer to home. In 2007, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography decided to include John Smith, which the Yorkshire Post marked by writing: ‘It’s not just an exercise in making toffs feel good about themselves through their dead relatives.’ It was noticeable to anyone who had ever had a full bladder in Tad that Sam Smith, owner of the adjacent brewery, did not make it into the dictionary, which was about par for a difficult family relationship.

In 1852, John Smith took advantage of Tadcaster’s hard water and his father’s money to buy Backhouse & Hartley brewery. Working with his brother, William, and nephews Frank and Henry Riley, he made it into a thriving business. When he died in 1879, the business was left jointly to William and Samuel, his other brother, who had a tannery business but no brewing experience. The will stated that it would then pass to their heirs. However, William had no heirs and the Rileys felt they were getting scant reward for their efforts. The seeds of discontent were sown.

William and his nephews shifted all the brewing equipment to a new site next door. This was not covered by old John’s will. In 1886, William died and the new brewery was run by Frank and Henry. Samuel Smith Junior, now the heir in accordance with John Smith’s will, was left with an empty shell of a building at the old site. He took legal action to retain the Old Brewery name and set up in competition as Sam Smith’s. John’s was the behemoth that would be taken over by corporate giants and supped by students in Wetherspoons all over the country. As for Sam’s, the place became increasingly eccentric as time moved on.

John Smith’s lorries were crammed with steel barrels and would power their way onto the high street and head for the motorways, but as kids in Tad it was common to see Sam Smith’s white shire horses pulling ancient drays around town with a few wooden barrels on the back. They seemed to take pleasure in doing things differently, at least from the accursed John Smith’s. In a matter of yards on the high street you had a battle being fought between modern life and nostalgia.

It was not quite that simple, but Sam Smith’s has since taken its contrariness to controversial extremes. Banning bikers from pubs in 2017 was one thing, but closing a pub on New Year’s Eve 2011 because the landlord was allegedly overfilling glasses seemed a novel way to dust down the old Yorkshire cliché about the thrifty tyke. In The Spirit of Yorkshire, published in 1954, the splendidly named John Fairfax-Blakeborough, a First World War major and author of more than 100 books, wrote: ‘From very early days we find those born in the county of York lampooned on the one hand as half-witted country bumpkins, on the other as the shrewdest, most astute, sharp-witted keenest businessmen in the country.’ Perhaps Edwin Sandys, the sixteenth-century Archbishop of York, was right when he opined: ‘A more stiff-necked, wilful or obstinate people did I ever know or hear of.’

Humphrey Smith, a descendant of the original Sam, now heads the SS operation. Under his stewardship, a ban on foul language was implemented in his 200 or so pubs, mainly based in old mill, steel and mining areas of the north but with a few escapees. The Guardian quoted one landlord speaking on condition of anonymity: ‘He walked into pubs unannounced – he does this a lot – and found people swearing. The managers were sacked on the spot. It didn’t seem that fair. There are places Sam Smith’s have pubs where the only language people speak is swearing.’

The same article claimed that Smith had a habit of dressing as a tramp and posing as a customer to monitor his pubs, though it is easy to imagine such a disguise falling foul of his own bar rules. Mobile phones are another no-no. The swearing ban was most offensive, however, and Steve, an HGV driver, could not comprehend its implementation. Other locals pointed out that ‘jammy bastard’ might creep out inadvertently during a game of cards. A builder might lament a ‘bloody awful day’. One woman was so roused by the decree that she stood up and declared, ‘I’ll tell you what I think of the fucking swearing ban, it’s a load of bullshit.’

In 2021, the comedian Joe Lycett visited Tadcaster and set up a pop-up pub at the bottom of Kirkgate, opposite the Old Brewery and next to where Radio Rentals had long since died. It comprised a barrel, a few chairs and one frothy pint. A Sam Smith’s employee called the police, though the constable dispatched seemed more interested in meeting a celebrity than in upholding Old Brewery values. On his Channel 4 show, Lycett said that Sam Smith’s was the perfect place ‘if you love going to the pub but are not that interested in it being nice’. He also recalled the pensions regulator writing to Sam Smith’s and receiving acknowledgement that their ‘tiresome letter’ had been received.

I think of Brian Glover.

This gruffness harked back to 2015 and the only time Tadcaster ever made the national TV news, when the Grade II listed eighteenth-century bridge collapsed as Storm Eva flooded the town. The bridge was the artery from east to west – and, incidentally, had a Sam Smith’s pub at one end. Cut in two, the town needed a temporary footbridge in order to be reunited. The obvious site was on Sam Smith’s land. The brewery refused. A waste of money, they said. It was just PR nonsense, they added. A piece in The Times later suggested that the Sam Smith’s reaction was probably created by a bearded hipster working in a marketing agency in Dalston, but Tadcaster Albion was underwater and Yorkshire MP Robert Goodwill was ‘irritated’. An alternative was found.

Stiff-necked, wilful or obstinate, perhaps, this all fitted with the wider image of Yorkshire. The bridge saga was emblematic of the divide between insiders and outsiders, of the generation gap, of old and new, stereotype and myth-buster.

To start at the beginning, I had to go back to Tadcaster again, and so before long I was standing at the west side of this same bridge. My mum used to work a few yards away, on the third floor of a red-brick building, for the British Heart Foundation. Just along the river stood the church I had not set foot inside since my dad’s funeral in 1986. That was the year Diego Maradona beat England in the World Cup. I remember lying on the floor by the fireplace to get close to the TV set as the little genius heated his cauldron. My dad was in his green armchair behind me. Except he couldn’t have been. My dad died in April and the World Cup was July. It is another false memory. It turns out there are lots.

Along the high street was what used to be Guy’s café, a would-be bistro run by an effervescent Italian who was one of my dad’s clients. The office Dad moved to from Leeds was just behind that, near the Angel, the Sam’s pub that has white horses in the stables. It had all changed in one way and had stayed the same in another, yellow stone tainted brown by brewery smoke, no chip shop, no Guy’s, but bricks and water, and ale fermented in slate vats at Sam’s and steel ones at John’s.

Up the road I came to the Riley-Smith Hall. I had recently seen a photograph in The Times of people doing ballroom dancing there as evidence of the UK’s resilience during the pandemic. I had other memories. I was a callow teen in the 1980s with a part-time job for a freesheet called the Tadcaster Extra when I went to interview Big Daddy, a middle-aged wrestler from Halifax who was really called Shirley Crabtree and was long famed for wearing a leotard and beating superior athletes by hitting them with his blubber.

It was easy to dismiss wrestling as tacky, a coliseum for blue-rinsed pensioners to wave their false teeth at Mick McManus in Batley British Legion. It always seemed to be Batley when it was on ITV. The Queen liked it. So did fashion photographer Terence Donovan and artist Sir Peter Blake. Greg Dyke, then head of ITV sport, did not, and pulled the plug on wrestling in 1988 because ‘we were stuck in about 1955 and wrestling clearly wasn’t a proper sport’. He had a point. It was vaudeville, The Good Old Days with Boston crabs, panto with teeth. In the flesh, the thing that was most noticeable about Big Daddy was the flesh. I asked him if wrestling was fixed. He sighed and said: ‘The pain’s real.’

Big Daddy’s father was a rugby league player. His mother was a blacksmith’s daughter. Shirley Crabtree was on the books of Bradford Northern rugby league club but got into fights and became a lifeguard in Blackpool. Then he turned to wrestling. His wife made a chintzy costume from their sofa and he made the Guinness Book of Records (for his chest size) and This is Your Life (for the other bits). He was a star. Was it fixed? Well, the year after we met, he did his trademark bellyflop on an opponent, Mal ‘King Kong’ Kirk, who it turned out had a heart condition. Kirk was dead by the time he got to hospital. Big Daddy, a moniker borrowed from the Tennessee Williams character in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, retired six years later and became Shirley Crabtree again.

The demise of wrestling shows how trades can change over time. John Smith’s is now owned by Heineken. The Tadcaster Tower Brewery, the third in the town, directly opposite the junior school, became part of Bass Charrington and then Coors. I once had a ‘fight’ outside the school gates. I was 10 and had tripped an opponent playing football at lunchtime. ‘I’ll get you after school,’ said Damon Bainbridge.