13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

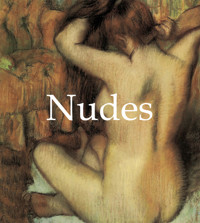

Just as there is a fundamental difference in the use of the words “naked” and “nude”, the unclothed body can evoke a feeling of delight or shame, serving as a symbol of contradictory concepts – beauty and indecency. This book is devoted to representations of the nude by great artists from antiquity and the Italian Renaissance to French Impressionism and contemporary art; from Botticelli and Michelangelo to Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and Botero. This beautifully produced book provides a collection that will appeal to all art lovers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 64

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Jp. A. Calosse

© 2023, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2023, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© 2023, Estate Masson/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Balthus/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Munch/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/BONO

© 2023, Estate Bacon/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/DACS London

© 2023, Estate Picabia/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

© 2023, Estate Man Ray/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Duchamp/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Denis/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Beckmann/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/VG BILD KUNST

© 2023, Estate Ernst/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Larionov/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Picasso/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/PICASSO

© 2023, Estate Leger/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Bonnard/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Dufy/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Magritte/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Man Ray/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Kingdom of Spain, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/VEGAP

© 2023, Estate Valadon/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP,Paris

© 2023, Estate Lempicka/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA

© 2023, Estate Wesselmann/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© 2023, Estate Brauner/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© 2023, Estate Raysse/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© 2023, Fernando Botero/Marlborough Gallery

© 2023, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/Wichtrach, Bern

© 2023, Lucian Freud

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-826-5

Contents

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553)

Diego Velázquez (1599-1660)

Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918)

Félix Vallotton (1865-1925)

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920)

Egon Schiele (1890-1918)

André Masson (1896-1987)

List of Illustrations

The Bather of Valpinçon (The Great Bather), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1808

Oil on canvas, 146 x 97.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Foreword

“I wished to suggest by means of a simple nude, a certain long-lost barbaric luxury.”

— Gauguin

Doryphorus (Spear Carrier), c. 440 BC

Marble copy after a Greek original by Polykleitos. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples

Just as there is a fundamental difference in the use of the words naked and nude, the unclothed body can evoke a feeling of delight or shame, serving as a symbol of contradictory concepts – Beauty and Indecency. This distinction is explored by Kenneth Clark at the beginning of his famous book The Nude. Earlier still, Paul Valéry devoted a special section of his essay on Degas to this subject.

It is that which provides grounds for separating depictions of the nude body as a special genre. Deriving from the Ancient World’s cult of the beautiful body and celebrated by the artists of the Renaissance, the nude became an inseparable element of works belonging to various genres. Here there is a whole range of gradations – from the sanctified nude of Christ in His Passion to the extremely free nakedness of nymphs, satyrs and other mythological figures.

This indicates that for a long time the nude was required to be placed in a subject-genre context, outside of which it was perceived as something shameful. The evolution of European painting provides a good demonstration of how the bounds of the possible were expanded and the degree of aesthetic risk in this region decreased. If the word nude might sound odd when used in reference to the noble bareness of Poussin’s characters, it is entirely acceptable for Boucher’s unclothed figures.

The relative autonomy in the depictions of the bare body, which can be taken as a sign of the formation of a specific genre, is a fairly late phenomenon. Théodore Géricault’s Study of a Male Model, for example (Pushkin Museum) is of particular value. It is indubitably a preparatory work, a study of the naked body, and its ancillary character is evident, but a view in retrospective changes the meaning and value of depiction, since today we see this model as one of the future characters in the drama acted out on the Raft of the Medusa.

The hand of the twenty-year-old Géricault possesses the power of a genius. The energetic chiaroscuro moulding endows the painting with sculptural qualities, but a superb sense of rhythm harmonizes the illusion of volume with flatness. An expressive contrast to Géricault’s study is provided by Thomas Couture’s Little Bather (The Hermitage Museum). The motivation for the nude is of no fundamental significance (the painting has also been called Girl in a Garden), since the girl incarnates sinless beauty and naïveté.

Barberini Faun, c. 200 BC

Marble copy after a Hellenic original, h. 215 cm. Glyptotek, Munich

David, Donatello, c. 1430

Bronze, h. 185 cm. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1484-1486

Tempera on canvas, 180 x 280 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

David, Michelangelo, 1501-1504

Marble, h. 410 cm. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence

Self-Portrait, Albrecht Dürer, c. 1503

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Ignudi, Michelangelo, c. 1508

Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museums, Rome

Eloquent testimony to the maturity of the genre comes with Renoir’s magnificent Nude in the Pushkin Museum collection. It seems that all the merits of French taste in painting are reflected in this image of a gloriously flourishing nude. With the elusive combination of natural stance and pose, Renoir achieved just as subtle an effect as with the richness of his palette. The artist’s brush revels in the delights of the nude with that immediacy, which is possible only in the spontaneous relations between painter and model.

At the same time, Nude signals the fact that the model is already the sovereign heroine of the painting. In this context it is worth recalling that, according to his own words, Degas was representing honest women, who when naked were only engaged in their own affairs. It’s as if they were seen through the keyhole. Degas’s models are indeed entirely independent. His image of nudity is self-sufficient in terms of subject and aesthetics.

His celebrated series of nudes – bathing, washing, drying themselves – represent a whole world of intimate feminine daily existence. Yet for all the life-like naturalness of his motifs, the expression “daily existence” does not prove entirely correct, as the bodily motions of his nude women find their source of inspiration in the ancient Venus. Was that not what prompted Renoir to compare one of them with a fragment of the Parthenon?

Of course, we are not talking here of any kind of mythological associations, but about an unconditional precision of line, classical clarity of form and the special effect of pastel with its “foamy” texture, reminding us how the goddess surged into the world. It is a well-known fact that Degas practiced photography. He was attracted by the unpremeditated composition of the snapshot – a quality that he so valued in art.

“He composes scenes,” Yakov Tugendhold wrote about Degas. “He arranges figures and draws out types in a way which only the camera could do. But look more attentively at his ‘snap-shots’ and you will see in them a profound deliberation and an intent with regard to colour. Using a Japanese compositional device, Degas narrows the frame of his characters, placing a hand holding a fan or the sounding-board of a violin in the foreground.