15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

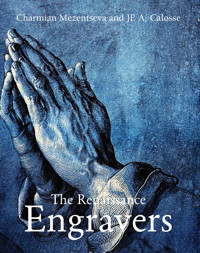

This ambitious work allows the reader to discover the art of engraving in Europe from the 15th to the 16th century. The engravings of the Renaissance masters are considered models of artistic perfection, often studied and frequently copied.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© Sirrocco, London (English version)

ISBN: 978-1-78310-721-6

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Charmian Mezentseva

JP. A. Calosse

The Renaissance Engravers

15th–16th Century

Contents

Introduction

Plates

Catalogue

Bibliography

Introduction

In Russia, active interest in the art of the European print developed in the course of the eighteenth century, and it was then that large scale collecting of impressions began. The Hermitage collection was formed mainly during the latter part of the eighteenth and the early years of the nineteenth century. The prevailing taste of the period favoured, above all others, works by the leading masters of the high Renaissance; these were regarded as models of artistic perfection, to be carefully studied and sedulously imitated. Best represented in the Museum’s collection are prints of the Italian and the German schools. They include a great many engravings by Marcantonio Raimondi and artists of his circle, and a large number of chiaroscuro woodcuts of the sixteenth century; also, many superb impressions of prints by Albrecht Dürer, and a multitude of examples of the art of the so-called Kleinmeister. Yet for all that we have to admit to some lacunae which can be attributed to limitations of taste of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century print collectors. The Hermitage possesses no impressions dating from the beginning of the fifteenth century, which would illustrate the earliest phase in the history of print-making, and has only a few works from the second half of that century. The collection includes no examples of Netherlandish fifteenth-century engraving; a very small number of sheets by the Italian artists of the quattrocento; and hardly any French fifteenth-century prints – these, for some reason, failed to attract Russian collectors.

The choice of prints for this volume has naturally depended on the general character of the collection, and cannot but reflect its limitations. No claim is made to be presenting a coherent picture of the evolution of European graphic arts during the Renaissance. The main aim of the book is to illustrate every aspect of the art of the print in fifteenth and sixteenth century Europe, while attempting, at the same time, to give an idea of the scope and content of the Hermitage collection.

Earliest among the prints included in this volume are three works by Master E. S., the renowned German engraver active from c. 1450 to 1467 in Switzerland and the Upper Rhine valley, somewhere between Constance and Strasbourg. These are The Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bench between St. Barbara and St. Dorothy (L. 75), St. John on Patmos (L. 151), and The Queen of Shields (L. 235) from The Small Set of Playing Cards.

Plates

1. Master E. S. (fl.c.1450–1467),The Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bench between St. Barbara and St. Dorothy. C. 1450. Engraving. 142 x 102 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 149672; Lehrs 75; Geisberg, Die Anfänge, p. 82

The Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bench between St. Barbara and St. Dorothy belongs to the artist’s early period, the beginning of the 1450s. The print was repeatedly copied in the fifteenth century, and was even reproduced in oils. Its popularity seems chiefly due to the choice of subject which contemporaries found very appealing. St. Barbara and St. Dorothy were both martyred virgins who suffered death by beheading for remaining true to their Christian faith. They are shown standing on either side of Mary, who is seated upon a grassy bench cut from turf and enclosed by planks, which is symbolic of her purity. By representing the Virgin Mother of God with two virgin saints, the artist sought to extol Christian martyrdom and to honor the cult of virginity, greatly venerated in those days.

2.Master E. S. (fl.c.1450–1467),St. John on Patmos. C. 1460. Engraving. 205 x 142 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 149673; Zanetti, 2; Lehrs 151; Geisberg, Die Anfänge, p. 100; Master E. S. Exhibition 33

St. John on Patmos (L. 151) is one of the best surviving prints by this artist. It is notable in particular for the rare perfection of its rendering of plant and animal motifs, which are in no way inferior in precision and vividness to the master’s best works in this field, such as his pictures of animals on playing cards. Though in fact belonging to Master E. S.’s middle period, the engraving bears marks of deliberate archaization: to imitate the effects of earlier prints, the artist rejects the method of cross-hatching which he had already employed in some of his works, and confines himself to the techniques used by his predecessors at a time when engraving on metal was still in its infancy.

3. Master E. S. (fl.c.1450–1467),The Queen of Shields. C. 1463. From The Small Set of Playing Cards. Engraving. 100 x 70 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. No. 151380; Passavant 206; Lehrs 235/I

As regards its technical aspect, The Queen of Shields (L. 235) is typical of the master’s productions of the early 1460s, in that it shows the use of punches, and a deeply cut outline combined with very light hatching. Only a strictly limited number of good impressions could be taken from a plate prepared in this manner. Soon after Master E. S.’s death, the plate had to be reworked; this was done by Israhel van Meckenem. Apart from the Hermitage sheet, there is only one other surviving impression of The Queen of Shields printed from the author’s plate in its original state.

In spite of a certain rigidity of attitude, the figures of Master E. S. are not devoid of grace and charm. His work stands out from the highly expressive German engraving of the period as a lyrical version of Late Gothic, tinged with a mood of gentle melancholy.

4. Anonymous German Master of the Fifteenth Century,The Passion Series: Sheets 1–8.C. 1470–80. Reversed copy after an engraving by Master E. S. (Lehrs 201). Engraving. Diameter 26 mm. Provenance: Amsterdam; Emperor Alexander I, 1809; Count; Piotr Suchtelen, 1836; Inv. Nos. 151369–151376; Undescribed, unique

The style of Master E. S. was influenced by that of the sculptor Nicolaus Gerhaert van Leyden, who introduced into the plastic art of Germany the dynamic effect of draperies. Paintings by Rogier van der Weyden and his followers, as well as pre-Eyckian miniatures of the Franco-Flemish school, also had a share in the formation of his style. In his turn, Master E. S. exerted a strong influence on the art of the period. This is attested to by the existence of a large number of copies of his prints, not only of German but also of Netherlandish and Italian production. Certain plastic motifs originating with him came to be widely used in sculpture and the applied arts. The series of roundels engraved with the subjects of The Passion (L.) in the Hermitage collection, published in our book – supposedly, the only surviving copy of a sheet (L. 201) by Master E. S. dating from the 1470s – is further evidence of his exceptional popularity with the public of his day.

Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491) was the first of the German engravers who deserves to be called a genius. His oeuvre is more completely represented in the Hermitage collection than the work of Master E. S. Included in this volume are several of Schongauer’s prints, dating from different periods and giving a general idea of the evolution of his style.

5. Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),Christ as a Man of Sorrows between the Virgin Mary and St. John. C. 1471–73. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 200 x 158 mm. Watermark: Gothic p with staff and flower. Provenance: Academy of Fine Arts, 1931; Inv. No. 272042; Bartsch 66/II; Lehrs 34/II

Christ as a Man of Sorrows between the Virgin Mary and St. John (L. 34), created between c. 1471 and 1473, is probably the earliest of all known prints by Schongauer. As was often the case in Netherlandish art, a mystical scene is set here within architectural framing, as if seen through a church window: an allusion to the idea that the temple is the House of God.

6.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),The Adoration of the Magi. C. 1470–75. II for The Life of the Virgin series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 252 x 170 mm (cut). Watermark: Gothic p with flower. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154664; Bartsch 6; Lehrs 6/II; Shestack 39

The Adoration of the Magi (L. 6) and The Flight into Egypt (L. 7) for The Life of the Virgin series (L. 5-8), executed between c. 1470 and 1475 – two other early works by this master – are also marked by strong Netherlandish influence. Certain compositional elements of the former recall the works of Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes and Dirck Bouts: we find here similar types, a great number of figures, and a distant landscape presented as if seen from an elevated viewpoint. But his impressions of Flemish art are transformed by the master’s individual temperament; and the drawing is marked by a purely Schongauerian vigor. Some parts of the landscape background in this work, as well as in his famous Peasant Family Going to Market (L. 90), reveal an essentially novel attitude: they are based on direct observation of nature, and had probably even been recorded in sketches from life in which the engraver came close to understanding linear and aerial perspective. Innovations are used side by side with traditional devices; thus, the outlines of the barren crags vary the old scheme common enough in the devotional pictures of the time.

Schongauer had a brilliant gift of composition. In The Adoration of the Magi (L. 6), his manner of presenting distance is calculated to convey an idea of the great length of the Magi’s journey. The procession of the travelers from afar is seen at a moment when, having made its way around the foot of the bare and impassable mountain range, it is moving straight forward in the direction of the spectator. The riders in Oriental costumes towering above the crowd render the walkers insignificant or screen them from sight, so that only some heads are left visible here and there, to give an impression that the train is endless, extending, as it were, into infinity. This compositional device was employed by Dürer in his woodcut of the same title (B. 87) executed c. 1504.

7.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),Peasant Family Going to Market. C. 1470–75. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 160 x 163 mm. Watermark: Triple mountain with clover leaf. Provenance: Johann Peter Maria Cerroni (Lugt 1432); before 1830; Inv. No. 276679; Bartsch 88; Lehrs 90; Shestack 34

8.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),The Flight into Egypt. C. 1470–75. III for The Life of the Virgin series. Signed in monogram; Engraving. 252 x 169 mm. Provenance: Johann Peter Maria Cerroni (Lugt 1432); acquired before 1830; Inv. No. 143804; Bartsch 7; Lehrs 7; Shestack 40

The Flight into Egypt (L. 7) is one of Schongauer’s masterpieces. His rendering of details is strictly lifelike and accurate; yet he uses, at the same time, the language of allegory: each of the objects has been chosen not because it just happened to meet the artist’s eye, but because it has a certain symbolic significance, and may serve as a key to some religious or poetic concept.

Schongauer’s interpretation of the story shows that he was familiar with the apocryphal Gospel known as Historia de Nativitate Mariae et Infantia Salvatoris (XX) dealing with the infancy of Christ and the miracles of that period. Following this source, the artist depicts the palm trees which grew up in the barren wilderness in answer to the prayers of the Christ Child, so as to shelter the wayfarers from the scorching rays of the sun, and to give them sustenance.

Standing on the left is the Dragon-Tree, associated, in the beliefs of the time, with the Tree of Eternal Life which once grew in Paradise. According to a Spanish legend elaborating the narrative of the apocryphal Historia, during the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt, evil spirits in the form of dragons entered the Tree to compel men to worship them; but on the approach of Christ they were cast out, and the Tree bowed before Christ in gratitude.

On the trunk of the Tree and at its foot, Schongauer represents several lizards. These creatures were traditionally identified with dragons: for instance, on the left wing of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych Earthly Paradise, (or The Garden of Earthly Delights, Prado, Madrid), there is a depiction of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil with the serpent twisted ’round its trunk, and satanic salamanders below which resemble the lizards in Schongauer’s print. These moist and scaleless creatures, crawling on their bellies, were regarded as identical with the dragon; this detail in his print shows that Schongauer was illustrating not only the famous apocryphal Gospel, but also the accompanying legend depicting the defeat of the forces of evil who fled before Christ’s holy presence.

The Historia de Nativitate Mariae et Infantia Salvatoris tells how, during their flight into Egypt, the Holy Family were attended by friendly animals. Schongauer’s landscape includes several animal figures, also invested with allegorical meanings and, in a way, expressive of the pantheistic tendency inherent in medieval Christian mythology. The stag, a symbol of Christian thirst and zeal for God, was one of the principal emblems of Christ, as ancient as the fish and the lamb. The parrot, which signified benevolence and beneficence, was an emblem of the Virgin Mary.

Schongauer’s interpretation of the story of the Flight into Egypt was at a later date followed by Dürer who, dealing with the same subject in his woodcut of 1504, illustrated the same source in even greater detail; for he presented not only the palm-trees, the Dragon-Tree, and the lizard devils in flight, but also the brook which, according to the apocryphal Gospel, sprang from the ground before the Holy Family. It is significant that Dürer’s composition also includes the ox, a symbol of the future sacrificial death of Christ, and a plank enclosure, a symbol of Mary’s virginity, and of the Christ-child’s divine origin.

9.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),The Betrayal and Capture of Christ. C. 1480. II from The Passion series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 163 x 117 mm. Watermark: Gothic p with flower. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154662; Bartsch 10; Lehrs 20; Shestack 52

In his Passion series (L. 19–30) of c. 1480, one of the prints from which, The Betrayaland Capture of Christ (L. 20), is to be found in this volume, Schongauer is somewhat less dependent than previously on the Netherlandish style with its characteristic interest in the representation of infinite space. As compared with The Life of the Virgin series where the composition tends to develop into the depth of the sheet, The Passion set is distinguished by a tendency to arrange the figures in a kind of frieze. Here the artist may be said to have followed the tradition of expressive realism as exemplified in the art of his German predecessors, Hans Multscher and the Master of the Karlsruhe Passion. The influence of this tradition is also felt in the heightened drama and nervous intensity of his composition. Schongauer’s familiarity with the work of the German engravers of the older generation, such as the Master of the Berlin Passion, or Master E. S., is also manifested in his ordering of the figures, whose violent gestures do not “rhyme”. In its turn, The Betrayal and Capture of Christ (L. 20) exerted an influence on the work of successive generations of artists. A woodcut of the same title datable to 1507 (B. 34) from The Passion series by Hans Leonhard Schäufelein may serve as an instance of this.

Schongauer included in his Betrayal and Capture of Christ two plant motifs with a symbolic significance, which are juxtaposed to produce a strong emotional effect. They are the Verbascum thapsus, the great mullein, or shepherd’s club, used by Schongauer more than once in his scenes of the life of Christ as a symbol of His glory; and a withered tree, a symbol of death common in fifteenth-century art.

10.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),The Virgin and Child in a Courtyard. C. 1480–90. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 169 x 123 mm. Provenance: Yegor Makovsky, 1925. (Lugt, Supplément, 885a). Inv. No. 100975; Bartsch 32; Lehrs 38

A dead tree figures in another of Schongauer’s prints in our book, The Virgin and Child in a Courtyard (L. 38), also a work rich in symbols. Here the wall enclosing the yard symbolizes the purity of the Virgin and the dry tree alludes to the early death awaiting Christ.

11.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),The Crucifixion. C. 1480. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 195 x 151 mm. Watermark: Profile head with staff and star. Provenance: Yegor Makovsky, 1925 (Lugt, Supplément, 885a). Inv. No. 10097; Bartsch 24; Lehrs 13; Shestack 63

Over the years, Schongauer’s world outlook became increasingly dramatic and somber. His Crucifixion (L. 13), containing but a few objects associated with daily life, has for its background a mountain view so lofty and abstract as to invite comparison with the art of Duccio, or even with Byzantine icons. Not a single blade of grass grows on the rocks, nor is there a sign of any living thing; barren and lifeless, they are a veritable echo of death.

12.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),St. James the Less. C. 1480. VII from The Twelve Apostles series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 87 x 43 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910. Inv. No. 154661; Bartsch 40; Lehrs 52 (as Judas Thaddeus)

Like many other artists of his time, Schongauer engraved the cycle of The Twelve Apostles (L. 41-52). Vasari lists these among the master’s best works. One of them, St. James the Less (L. 52), is included here.

13.Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491),Shield with a Stag, Held by a Wild Man. C. 1480–90. IX from The Coats of Arms series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. Diameter 78 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910. Inv. No. 154659; Bartsch 104; Lehrs 103; Shestack 97

The series of Coats of Arms (L. 95-104) was created during Schongauer’s late years. They were supposedly intended as ornamental patterns for goldsmiths, or as a fifteenth-century equivalent of modern visiting-cards, or perhaps as bookplates. They may well have been conceived in the spirit of parody, as mock ensigns of honour. Vasari, however, took them quite seriously, as “alcune arme di signori tedeschi, sostenute da uomini nudi et vestiti e da donne” (IX, 260): several coats of arms of German nobles, supported by men, nude or clothed, and by women.

A sheet from this series, Shield with a Stag, Held by a Wild Man (L. 103), is illustrated in our book. The bearer in the shape of a human creature of fantastic aspect, believed in those days to live in the forests, signified a powerful defender endowed with the strength of a lion, and able to overcome all opponents in the service of the bearer of the coat of arms. The choice of the charges is based on medieval Christian symbolism. Thus, the mountain is meant to suggest divine presence; the stag is an emblem of Christ; and His attribute, the lily-of-the-valley, is allegorical of the well-being of the world, and the cure of the spirit.

14.Master A. G. (fl.c.1475–1490),The Entombment. C. 1480–90. X from The Passion series. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 144 x 107 mm. Provenance: Joseph Daniel Böhm (Lugt 271, 1442); Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154657; Bartsch 11; Nagler, Mon. 11; Lehrs 15/I

The Hermitage collection of German graphics of the pre-Dürer period is not large. Among its prints is a sheet by Master A. G. (fl. c. 1475-1490) who seems to have served a term of apprenticeship with Schongauer in his workshop at Colmar. The Entombment (L. 15), created in all likelihood in the 1480s when the artist was already settled in Würzburg, is marked by great delicacy of touch. Its engraving techniques bring to mind the manner of Schongauer. Not so its style; the acrid dissonances so characteristic of The Passion series by Schongauer, an artist unrivalled for his skill in the use of contrast while rendering movement, are not present in the print of Master A. G. He obviously preferred the undulating rhythm of Netherlandish art, as exemplified by The Entombment of Dirck Bouts (National Gallery, London), a painting close to our print in the arrangement of the figures.

15.Wenzel von Olmütz (fl.c.1475–1500),St. Simon. C. 1490. XI from The Twelve Apostles series. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 51). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 95 x 47 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 34361; Bartsch 40; Lehrs, Olmütz 42; old impression; Lehrs 42

Native of Bohemia, Wenzel von Olmütz (fl. c. 1475-1500) may also be assigned to the school of Schongauer, for of his ninety-one surviving works, forty-three are copies from the great Alsatian master. The art of Wenzel von Olmütz is represented in the Hermitage by several prints. Two of these, St. Simon (L. 42) and The Bearing of the Cross with St. Veronica (L. 16), repeat Schongauer’s compositions of the same subjects, executed during the 1480s. In his interpretation of the originals, however, Wenzel von Olmutz showed considerable independence: he rendered the tonal, dimensional and spatial relations freely, and varied the structural harmony of Schongauer’s prints by introducing a linear rhythm of his own, which imparts to his work a distinct individual flavor and lends it a peculiar charm.

16.Wenzel von Olmütz (fl.c.1475–1500),The Bearing of the Cross with St. Veronica. C. 1490. VIII from The Passion series. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 26). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 162 x 116 mm. Watermark: Small town gate. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 143805; Bartsch 11; Lehrs, Olmütz 11; Lehrs 16, old impression

17.Master P. W. of Cologne (fl.c.1490–1510),Two Soldiers with a Banner. C. 1500. Companion piece to Two Soldiers with a Halberd (Lehrs 15). Signed in monogram. Engraving. 101 x 64 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 144556; Bartsch 3; Nagler, Mon. 7; Lehrs 14

The Hermitage collection includes only a single example from the œuvre of Master P. W. of Cologne (fl. c. 1490-1510), Two Soldiers with a Banner (L. 14). This print, like all of his works, is distinguished by a sharp and elegant drawing style. The subject, as well as that of its companion piece, Two Soldiers with a Halberd (L. 15), may be assumed to reflect the author’s personal observations of Emperor Maximilian I’s campaign against the Swiss, of the year 1499. The Two Soldiers with a Banner, without a doubt, postdates Dürer’s Six Soldiers (B. 88) executed in 1496 – that work was quite obviously known to Master P. W. But it was created before 1502–3 when Master P. W.’s famous Deck of Playing Cards (L. 20-91) was produced, to judge by the fashions in dress and the general style of execution.

18.Master B. G. (fl.c.1470–1490),Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman.C. 1490. Signed in monogram. Engraving. Diameter 92 mm. Acquired before 1830. Inv. No. 143803; Passavant 30; Nagler, Mon. 33; Lehrs 37

Of the work of Master B. G. (fl. c. 1470–1490) who lived, in all probability, somewhere on the Middle Rhine, in the area of Frankfurt, the Hermitage owns two examples: Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman (L. 37), and The Arms of Rohrbach and Holzhausen (L. 40). The sheet representing the arms of the two patrician families of Frankfurt may be a copy of a drawing (now lost) by Master of the Housebook, another artist of the Middle Rhine area, who exerted a strong influence on Master B. G. The former work, of which a woodcut copy was made by Hans Schäufelein as early as 1535, in his Three of Acorns (G. 1112) for a set of playing cards, may have been inspired by such prints of Master of the Housebook as Young Man and Old Woman (L. 73) and Peasant Woman with a Yarn and an Empty Shield (L. 82).

While sharing with Master of the Housebook his interest in peasant subjects, Master B. G., who has a pronounced moralizing tendency, places a stronger emphasis on the more brutal side of human nature than did his predecessor. In his Empty Shield Held by a Peasant Woman (L. 37), the woman is represented as quite drunk, in the act of raising her skirt; the shield she is holding lacks a coat of arms, an ensign of honor; by her side is a jug, an object not infrequently used in the German and Netherlandish art of the period as an allusion to the low, carnal aspect of the female sex. The artist’s keen sense of the grotesque, and his vivid imagination, make up for the crudeness of the drawing, and give liveliness and meaning to his print.

19.Master B. G. (fl.c.1470–1490),The Arms of Rohrbach and Holzhausen.C. 1480–90. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 97 x 95 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?), 1885; Baron Alexander. Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932, Inv. No. 288669; Passavant 40; Nagler, Mon., p. 890; Lehrs 40, impression; 1856; Shestack 140

20.Monogrammist M. Z. (fl.c.1500),St. Catherine of Alexandria. C. 1500. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 124 x 87 mm. Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154666; Bartsch 11; Nagler 11; Lehrs 8

The two prints of the highly gifted Monogrammist M. Z., active in Munich about the year 1500, St. Catherine of Alexandria (L. 8) and The Embrace (L. 16), like other works by this master, are not copies but original creations of the engraver.

St. Catherine of Alexandria and two other prints, St. Margaret (L. 10) and St. Ursula (L. 11), form a graphic triptych dedicated to the cult of virginity and Christian martyrdom.

21.Monogrammist M. Z. (fl.c.1500),The Embrace. 1503. Signed in monogram. Engraving. 151 x 116 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?) 1885; Baron Alexander Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932; Inv. No. 288872; Bartsch 15; Lehrs 16; Shestack 149

The Embrace (L. 16) is an interesting illustration of the practice, common in medieval art, of investing each little detail with a double significance, and using both its direct sense and its metaphorical connotations. Thus, the open cupboard and the unlocked door suggest that the mistress of the house is a woman of easy virtue; this idea is echoed in the shape of the door-fastening, which is suggestive of a phallic symbol; while the mirror is an allusion to the vices of Vanity and Voluptuousness.

The work of Monogrammist M. Z. is a product of a peculiar artistic vision which, while still retaining some features of the past, is nevertheless oriented toward the coming sixteenth century. His love of Gothic elongated forms, of agitated, angular outline, of labyrinths of gracefully fluted drapery folds, links him to German fifteenth-century engraving. But his free handling of the burin, his spontaneity in the rendering of light emanating from a multitude of sources and producing reflexes and rich shimmering shadows, the airiness of his landscapes, and an almost impressionistic quality distinguishing them, are all features that were to be taken up by sixteenth-century art, and to grow into its leading principles.

22.Israhel van Meckenem (c.1445–1503),St. Agnes. C. 1490. Copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (Lehrs 67). Signed in monogram (cut). Engraving. 143 x 98 mm (cut). Provenance: Piotr Semionov-Tienshansky, 1910; Inv. No. 154665; Bartsch 119; Geisberg, Verzeichnis, 320; Lehrs 387

The prints of Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445-1503) included in this volume are copies from other artists, as are most of the works of this prolific master. They are St. Agnes (L. 387), a reproduction of Schongauer’s engraving (L. 67), and Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy (L. 521), a copy of a dry point print (L. 91) by the Master of the Housebook, both dating from the 1480s or 1490s.

23.Israhel van Meckenem (c.1445–1503),Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy. C. 1480–90. Copy after an engraving by the Master of the Housebook (Lehrs 91). Signed in monogram and inscribed: bocholt. Engraving. 146 x 119 mm. Provenance: Alfred Beurdeley (?) 1885; Baron Alexander Stieglitz; Museum of the School of Art and Design, 1932; Inv. No. 288866; Bartsch 194; Passavant 194; Geisberg, Verzeichnis 442; Lehrs 521; Shestack 206

By its content, the Coat of Arms with a Tumbling Boy