6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

With bugs in her skin and noise in her head, Riz is real and the rest are fake. What matters to her: Mark Rothko's art. So despite the horror of family time, it's a fine thing that a major Rothko show coincides with the global conference where her so-called Dad is such a big wheel. Holed up with VIPs at a heavily guarded hotel, Riz collides with a sharp-dressed assassin she calls The Man. As she plunges into a world of covert deals and power plays, Riz is befriended and betrayed by Russian and Syrian agents. And emotionally bruised by the leader of a violent anti-capitalist group in town to protest the conference. Told in Riz's breathless, insistent voice, the edgy friendship between the isolated teen and the travelling killer drives a thrill-ride through riot-torn London.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Epigram

Half Title

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

On the Level

Mark Wagstaff

Published by Leaf by Leaf an imprint of Cinnamon Press,

Office 49019, PO Box 15113, Birmingham, B2 2NJ

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Mark Wagstaff to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2022, Mark Wagstaff.

Print Edition ISBN 978-1-78864-936-0

Ebook Edition ISBN 978-1-78864-953-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press.

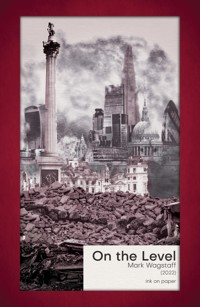

Cover design by Cinnamon Press using picture elements:

St Paul’s: 60459432 © Martinmates | Dreamstime.com

Nelson’s Column: 88848728 © | Dreamstime.com

frame: 166330056 © Shepherdingtheflock | Dreamstime.com

rubble: 139748744 © MrIlkin | Dreamstime.com and 146151181 © Naropano | Dreamstime.com

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress.

Is this stuff on the level, or are you just making it up as you go along?

Groucho Marx, Horse Feathers

On the Level

1

Such a damn simple idea. In London for that conference. Worst horror show since the last meltdown. But Dad was tight with the guy sent to save us. The global loans guy. Same week as the bitchingest retrospective. Ten rooms of Rothko.

TV was my best amiga then, because most times I went outside I got beaten up. Sick and wretched one night, I caught this Rothko edutainment and those pictures, man, those pictures soothed my bones.

Such a damn ordinary idea. Me and Dad head to the city, mind our own business, him with his global power play, me with Rothko. Only my Mother could screw that into a family occasion. Only she could decide her and her kids tag along. If I talk about her, I’ll need a truck of tequila.

Now Dad, he was with the band: big shot diplomat, he rated full security. Which means we all did. So we got stashed at this eight-star luxury prison—the London Royale Grange Plaza—directly across that Kensington street from the conference. Steep grey concrete, cops everywhere—not exactly Tahiti. But the rooms, man: my lounge with a big TV, those creamy low chairs only hotels have, shower, double bedroom—I had the whole Seven Year Itch going down. See myself, truly, living that way. When I brush the road from my hair.

So I said, a suite—lounge, bathroom, bedroom—exclusive to me. The lounge had these godawful pictures. Nasty non-art Rothko wouldn’t use to mop his blood. I was trying to lever them off the wall when I noticed the room had this extra door for no obvious reason. So I opened it, as anyone would. There was another door behind. Though my folks bought me a tie for a very expensive school, truthfully that place had nothing to teach me. I got educated from heavy metal and The Twilight Zone, so to me the risk was wholly real that through that second door there’d be another, and another, and each successive door would slam behind me, and I’d be doomed to scratch my last against some freaking door. You can see how that might happen.

Pulling a painful stretch, I wedged the first door with my foot and gently opened this unexpected other door. Daylight. A room. Still certain I’d entered another dimension where people drove Zodiacs and would call me kiddio, I stepped into a lounge—picture this—the exact, absolute same as mine, reversed. I mean the furniture. The furniture was mine reversed. I’d scored a deuce. Two TVs, dual music, double sets of bathroom freebies. Thinking this pretty fine, I tried the bedroom—yeah, another king bed. So this was my backup suite—I could take half the week sleeping one way and half the other.

Just then, something interesting and ghastly happened. That chk-chk-chock of a keycard, the brusque release of a handle. Somebody walking into the lounge. Maybe I panicked, maybe what I did was dumb: I drop-rolled under the bed. I mean, I could have pretended I was some nosy kid. But if my parents found out they’d take my suites away and I’d have to bunk on some bouncy castle mattress in their lounge. And, yeah, I did think I was smart enough to slip away when whoever was busy. So I hit carpet.

Pretty fast I knew the maids were just taking the money: under that bed was dust and lint and this taste of hideous hairs. It was also tight and close and scary. I got footsteps from the lounge: loud, then stopped, then faded, then stopped. Then a door shutting, and another. Not that I unpacked anything personal, but whoever must have seen into my place and I felt pretty invaded. Those footsteps moved with purpose—lot of opening and closing cupboards and drawers. I got shoes—hard shoes—on the bathroom floor, then a clatter of toiletries. Whoever was checking the place.

Those shoes strolled into the bedroom. The wardrobe door snapped back, hangers chinged and clattered. A limited commotion—they were tapping the walls. Man, I got to tell you, I was rushing like I smoked a half soused with special sauce. The shoes, those damn shoes, started round the bed. Deliberate, firm, parking just east of my midriff. Damn nice shoes: kind Dad wore, though more polished and consequent-looking. And charcoal grey trousers, neat, perfect length, not laying over the shoes nor showing sock.

Staring into the sweet maple bedframe, I tried convincing myself that whoever would leave, just go. Till I saw more and more those trouser legs scissoring-down, steady and sure—not one squeak of knee bone. Then the jacket swept across my view like poorly-hung scenery. Then a sideways face, staring into mine.

‘Are you asthmatic? You breathe too loud. What you here for?’

Truly, I was that near to crying like a girl. ‘I’m here for Rothko.’

‘Get up.’

An awkward shuffle, and being laced with dust and crap made worse an already thorough disadvantage. Way taller than me—which is to say nothing—he was also taller than Dad and that was impressive. Devilish smart, that English-cut suit. To say his voice was cold is to say the Titanic had issues with frost.

‘What you doing here?’

Channelling Lara Croft, I gave it every inch of teenage scorn. ‘There’s a door into here from my place. Thought this was my place too. I mean, wouldn’t you hide, if you didn’t know who was coming in? You could be crazy, all I know.’

The Man—forever I think of him as The Man—took one second to get to the root. ‘Why you acting the kid?’

That persecution so did it. I gave him the dagger-look and made to walk—surprised and massively scared when he slapped my shoulder. Physically with his actual palm, the heritage invitation to take it outside. Now, I had plenty fights in school, beat down by girls in sweaters pumped on chicken grease. That was kids. I wasn’t down with the etiquette of fronting a grown man. With my Dad’s fine name and the fact I’d done nothing illegal, I needed foot-stomping anger. What I got was a real deep blush.

‘You are a kid.’

‘I’m new adult.’

‘You’re an idiot.’

‘Huh?’

‘You hide someplace with no exit.’

I never did get round to ask where he’d hide. I trailed him through his lounge, feeling weirdly cheated that he thought the matter settled.

He bust open the back-to-back door. ‘You from the next room? Why you here?’

‘I said: for the Rothko show.’

‘Alone?’

‘Yeah.’

And d’you know what that guy did? Only followed me into my room. My actual room. Course I asked did he think that was okay, course I showed him my middle finger. By then he was giving my place the care he gave his.

‘You a cop? Cops need warrants.’

‘So I’m not a cop.’

‘I’m calling security.’ Could have said I was calling Dad, not.

‘Would you say you’re popular?’

That messed with my head. What I heard: would I stay long under floorboards without getting missed. Strangely, though, some part of me thought, really, he was asking.

‘You’re what? Sixteen?’

So I looked older to him. Cool. ‘Yeah.’

‘It’s twenty minutes since we got acquainted. You haven’t taken a call.’

‘My phone’s to mute.’

‘Why do that?’

‘Chill time, y’know. For my soul.’

He moved slowly to the through-door, checking me with heavy distrust. ‘Tell you what’s going to happen. I’ll close this now. Lock my side. You damn better lock yours. I find one ginger hair messing up my rug, you’re hitting the bricks, get me?’

‘Sure.’

‘Damn sure.’

His shape still filled the air when the doors slammed behind him.

After my neighbour’s invasion, I felt to lay low the rest of the night. Getting dragged to the restaurant by Mum at her worst so wasn’t it. It’s majorly obvious we were not what you’d call an eating together family. My memory’s thankfully hazy, I think back then my sister only ate stuff cut pussycat-shapes. But because this was some fake holiday, and because Dad faked he liked it, and because we’re damn good at faking, we faked a Waltons dinner.

Most any guidebook says you don’t eat at the hotel. But it got late, and the horror of getting the little dweebs scrubbed and ready, and security—always security—meant Mum told Dad we’d do fine in that chandelier-crusted slum. These days I live places that melt when it rains, so naturally I hated the granite, the marble, starched linen, and starchier, up-themselves waitresses. Man, I could deal with them now.

Without TV, the kids had nothing but kick the chair legs. Worse, I wasn’t allowed music—I had to listen to their voices. The food was these potty-scrapings adults eat. So was the conversation. Masochistically, I tried getting traction on Rothko. But they only knew him as cause of the holes specking my bedroom ceiling, where I pinned his greatest hits. Of course, Dad copped out a wholly-predictable fashion, taking messages and calls on matters of national importance. Different rules for him.

Starved for distraction, I checked for The Man. I could maybe have claimed him as an acquaintance—anything to get me away from the changelings finding stuff not to like about ice cream. I lost track the number of times I had to explain to my sister how vanilla is black.

Who I did see swanning around was the maître d’—the tight-dressed guy who stiffed Dad so completely over the room bookings, which caused the little kids to bawl and finished with me having sole use of a suite I sorely wanted to get back to. The maître d’ was showing the restaurant—indeed, displaying it with a generous sweep of his arm—to a tall, surly woman busting a really neat sand-drab suit. Even at distance, the maître d’ looked keen to reassure her, while she found everything a source of wrist-flicking annoyance. I couldn’t think why she might look at me, just knew she did.

Not till I tried to leave did Mum ask if I was going to ‘that gallery’ tomorrow. Well, yeah, what else did she think I’d do? Not feeling that answer, she squawked about family time right up till I left the room and—probably—after.

When I stepped from the lift to head back to my suite, a stressed suit and earwig patrolled the hallway. Got to say, as a lone female, I wasn’t assured by his presence. He took an over-close interest—I mean, sure, I had the kit even then. But his trailing eyes suggested some other bad mischief. So much, when I shut the door, I searched that suite top to toe. Checked under my bed, every cupboard and drawer; smacked back the shower screen so hard one of the hinge bolts bust. I found nothing and wasn’t content there was nothing to find.

A suburban kid, I had this sketch for big city nights. Flashing billboards, always cool—the room lit, then dark from neon, intermittent. Traffic below: cars pumping bass, chicks laughing, a clubby sense of night independent from drab day. Step to the window—hot, damp air makes everything dangerously slippy. Lit apartments across the way—a woman named Blanche or Adele or Nina or Joey getting changed beneath a harsh, bare bulb, getting made for midnight downtown. I’d be there, sipping something long with ice and limes, waiting the big deal to happen. So what happened? The air con buzzed, the night set still, and that’s all.

Numbers beside me said 2:32am when I woke still dressed. Woke to something new about the dense silence. A phone ringing through the wall. I slid to the joining door, trying to hear past the squabbles in my head. That murmur: the low, low sound of a big man talking soft. I guess he was pacing—a restlessness leaking through the cement. I saw him walk, gesturing, shaking his head. That pointing move he pulled: I bet he was pointing, pacing with his phone. The Man next door, on some whole other business.

2

Through a ton of motels where I learned or didn’t learn Spanish, when vanilla-scented camareras asked how the world was treating me, I thought they meant I looked as crap from lack of sleep as I did that morning. As daylight dirtied the blinds, the grey slab building across the street was busy. Barriers blocked the road, dodged-around by presented-looking women in serious suits. Everyone accessorised with slab laminates. Every guy a cop.

I checked the hall door was super-locked, dragged an armchair against the charm school entrance, and caught a shower. Like always with hotels, the shower ran high Arctic one second, uptown Zambesi the next. Jinking the knobs made zero difference, the whole thing tediously hateful.

Dumb as I am, I got very aware of my rawness, just tiles and plaster from the bathroom next door. Stupid, I felt shy. Through steam that softened the light into some gothic, misty morning, the water inside of the shower screen hung vivid as sunburnt ice. Those moments—regular to me—when I get overtaken by the massiveness of how things exist. When the way things exist gets under my skin and flays me. Sure gets distracting when I’m gunning my Harley down a wet highway. I get bewildered, I guess, by cracks across walls, how trees twist, the pathways of cuts in my skin. I get seasick from patterns of leaves. I get shipwrecked from Rothko.

Takes a while, after those moments, to come back level. When the shower burnt my flesh and cold from the air con hit, flung from fire to ice, I towelled and dressed, the neat cottons and linens I’d bought for the city stinging my skin.

Fixing my face, I got that sound again: his phone next door. I find this hard to put over without sounding hippy, but something to how his phone rang made me think these calls were more significant, somehow. I could no more imagine him take a courtesy call than watch game shows.

A different slab guy furnished the hall, though with the same troubled tailoring. Always, I’m uneasy with random heavies. The whole city muscled-up for the conference—I knew Dad’s job, he rolled with the grownups. That didn’t explain the guy stood watch in my hall. Behind his shades and waxy skin, seemed to me he was worked by wires. That made a brick of lead in my gut as I went downstairs.

From the lift I tumbled into a tide of linen and handheld devices. Everyone so perky and focused, I wanted outsider cool but just felt uninvited.

This goofball guarding the restaurant hassled me for ID. ‘Name and room number.’

‘What?’

He looked me down. ‘To prove you’re a guest.’

‘I have a suite. Riz Montgomery.’

So he checks his rinky list. ‘I have an Amelia Montgomery.’

Take a razor to my heart. ‘That is so much a typo. I’d fire the arse of who did that.’

Weirdly, the oaf seemed puzzled. ‘Are you waiting for your party, Miss Montgomery?’

‘Yeah, sure, I want Mum and Dad and the twinklets of Satan to make my misery complete.’

I’d only just soiled the tablecloth with my midnight velvet nails when this sweet-chocolaty waitress tells me they cook eggs to order. I cannot begin the horror of any cooked breakfast. ‘No, just coffee and toast and Wackios.’ Tell you, Wackios make a fine meal, straight from the pack.

She gave me this practiced look. ‘If you prefer cereal there’s a serve-yourself counter.’

Bottling my fear of the bright, chattering crowd, I went to the counter but found just muesli and crap. The toast she brought was cold. By the feel of it, it was cold the day before too. A slug of coffee and I’m making to walk, when I clock the tall woman I’d seen before—wearing the same or another sandy suit—her hands describing shapes with agile anger to a crew of dodgeball-headed cops. These officers—meaty guys with years on the street, I guess—looked suitably thrilled to have a strong, ethnic woman bossing them round.

Now that woman did not have a laminate. She didn’t need one. The starch of her shirt and razor creases gave her whole ID. She broke off talking to intercept me. ‘Hello. Amelia, isn’t it? I’m Detective Chief Inspector Salwa Abaid. I’m security command for the hotel.’

I was just trying to leave against the tide of starving delegates, I never thought I’d get recognised. How did she recognise me? ‘Oh yes?’ I said, like an idiot.

A flicker across her cheekbones hinted she made some decision about me. ‘We won’t inconvenience you.’ A lie from any cop. ‘Just the situation, you understand.’

Yeah, I mainlined rolling news. ‘The loan fund guy? I heard he’s not popular.’

‘There are always challenges.’ Her smile so many ways worse than her scowl. ‘Be assured, though. We have security arrangements for immediate family members of vital staff.’

With the laminate crowd making whoopee around us, a tiny, fatal delay crept between what she said and me getting what she said. Already, she turned away, giving her men instructions.

‘Excuse me.’

Her look said we were done.

‘What does that mean, family members?’

At school I was used to nasty, dried up women telling me I should consider the words just said. Usually while girls around me were laughing. Detective Chief Inspector Salwa Abaid was no way dried up: very fine bones, fine skin, powerful—guess I’m meant to say a strong role model. Her date palm eyes had exactly the look I knew from school. ‘We, the police, the security services, we understand it’s not sufficient just to protect key personnel. For key personnel to function, they have to know their families are safe. We’ve got your back.’

I’d get a good laugh from the notion my family wanted me protected. What Abaid meant was wholly more disturbing. ‘You have a file on me?’

She stroked down her jacket where she kept her gun. ‘If you have concerns the liaison team are here to assist.’

By the time Mum messaged to say they started breakfast, I’d hit the street.

Grazed-looking guys in brown Harringtons, hoisting shoulder cameras, filmed gleaming women saying the same things over and over. You could only walk the hotel side of the street, single-file behind concrete barriers. Knightsbridge at the corner, that well-heeled, overplayed avenue ablaze with sunlight. You can’t do crisis without retail. High end traffic jammed both ways, and blondes—a city stacked with blondes. Girls every colour, all blonde.

I already checked which Tube to get and once I made it onto that cramped cylinder of dirty metal, I had a whole city-girl thing going on. A clear shot of myself as a young woman riding the train, rushing beneath a landscape wholly high-rise. Some cool place I was part of: a chick with a mouthful of truth, intelligent eyes, the city mapped to her synapse. Not scared, not makeshift—the girl upstairs whose air con breaks, so she climbs in through your window.

Each station brought a compelling flow of Black girls, pumped little chicas among mad old fools stained from years of glum weather. Tidy Arab women in serious jackets, dudes busting baggies and skateboards, looking straight at me so I looked away. Families that weren’t my problem, struggling luggage. A poised older woman, her guide dog comfortably sprawled against the seats. So naïve, I actually wondered how she got her makeup so perfect.

So I should have felt cool—the roach in the jelly being I couldn’t enjoy it. For all I felt strong in my head right then, solo and independent, each time I saw someone a bit off someway, I thought how many friends Detective Abaid must have, the embrace of security freezing my spine. Would they follow me? Did they bug my clothes? I checked my pockets, scratched the seams. What if they bugged my lingerie? My secrets, all laid open. Maybe they’d always been watching, right since I was a kid. I slumped against the door, overwhelmed with anxiety and, at the next station, fell backwards off the train.

Walking up from Charing Cross, even I couldn’t miss the National, tricked up with almighty banners of Purple Brown 1957, the colour-render on tent canvas not exactly authentic. Willy-waving by the curators, for getting the Rothko gig ahead of Tate Modern. Though really it was the sponsors—some US bank squeezing the culture nipple—that wanted iconic Trafalgar Square, not a steam shed south of the river.

None of which meant spit to the miniskirt leggings and tie-dye flowing up to the door: art school chicks, nursing cartridge pads my x-ray eyes confirmed as portfolio work for glamourous lives under construction.

Glad at least of strong lashes and talked-up cheeks, defiantly freckled, I lined for the paydesk with the amateur beards and gents of a single nature. At least the crowd wasn’t touristy, none of that poor muscle tone you get with Monet or Renoir. I faced the elderly paydesk jockey.

‘Do you pay student rate?’

‘Er, yeah.’

Crabby old fingers pinched the air. ‘Your student ID, please.’

That whole scene of ID remains, to this day, unexplored to me. Clearly I was a student, I got a tattoo—not that I planned on showing her that. So I played along, hunting my pockets till I got told to pony or leave. I would have wished her herpes, but her looks and attitude guaranteed immunity.

Next came examination by gruff types with the x-ray thing. ‘I got to empty my pockets?’

‘And unclip your belt.’

‘My belt?’

This scrubbed-down, sensible-shoe type looked dumbfounded as I unwillingly popped it loose. ‘A cat head buckle? Really.’

Stepping through the main hall was to stumble in space, the ceiling high behind banks of lights that churned through green and ochre. A cool vastness where people—even smart people—got kept to their proper size. Big sculptures, metal and stone, awesomely sifting light. I ran my hand along a gleaming bronze, its cool solidity questioning the clammy catch of my fingers. Everything beautiful the big way, the way a girl’s unmade bed can be beautiful, when it carries the care and forgiveness of people who’ve needed her or been needed. Art is that or nothing. Ask Delacroix, man, ask Turner or Vincent or Marcus Rothkowitz.

The concept of Rothko might seem weird to folks with seedless-grape imaginations. But those pictures have been my endurance. A place like no other, where I can lay quiet and still. You love Rothko or you don’t dance with me.

Beyond the rope, the light respectful and sombre, the walls a tone so neutral it was nothing. Black cubic sofa blocks where sketchbook girls could settle. Rothko everywhere. Wall upon wall, room upon room—I actually felt myself not breathe, utterly stilled. Faced with Yellow and Orange, with Untitled 1950, I knew clarity, fields of pure life. Voices around said Rothko got abstract—bullshit, he never got abstract. He got clear, precise, fried on hard liquor. Not abstract.

Man, I dissolved in those paintings. When you thought you’d seen the most tragedy and joy, you found more. People were crying, it’s cool to cry with Rothko, you’re better for it. He was Oppenheimer and Gagarin. He was Elvis and Willy Wonka.

Don’t care it sounds dumb, I hit the floor in front of Black On Gray, feeling for every razor sting, while people flowed around me.

‘Of course,’ a woman said, above, ‘he was the first to paint empty pictures.’

No way. Anger pulled me around. I drag-raced off my knees with the clamour of someone climbing from a hole. ‘Bullshit.’

Humiliatingly, the woman didn’t notice, so I had to say it again.

‘Bullshit. You can’t be more wrong.’

This large-breasted middle-ager, buttoned and smocky just like Mum’s friends, looked me down with dog-ugly distaste.

‘You can’t be more wrong. They’re not empty. They’re full. They’re filled with… with…’

‘Hope.’ Male, quiet—hard and sure. ‘They’re filled with hope.’

I never heard that before, but the absolute certainty how it was said, the woman’s total disablement to answer, electrified my bones. I pivoted round. My neighbour, The Man, with the big snoot catalogue cradled open at Black On Gray. He read aloud, his voice the most violent calmness, “So much of Rothko remains—in a multiplicity of glowing presences, in a glory of transformations. Not all the world’s corruption washes high colors away.” In fact a quote, the eulogy Stanley Kunitz gave.

Still smarting, and wanting to be smart, I said, ‘He didn’t care for the haters.’

‘He cared for his work. You can go anyplace from there.’

‘To death.’

‘Especially.’ The Man gave a moment more to Black On Gray. Not just tidily dressed, perfect dressed. Not just the well-cut suit—starch white shirt, his classic tight-woven angle-stripe tie, his vintage, unflashy wristwatch: the type familiar from movies, an old Omega maybe. And cufflinks. Like blood stains, his cufflinks. Those stitched shoes I got such a view of under his bed. He didn’t dress to own the joint. He dressed to eat whoever owned the joint.

You may ask what he was and I could say tall, a foot taller than me. Brown hair, left side-parted, short at the sides, first speck of snow at the temples. Skin showing a little experience round the eyes. Blue eyes, deep and direct. I could say all that. Tells you nothing about what he was.

Those eyes scanned me. ‘We got off on the wrong foot yesterday. Reception didn’t notify me of young women checking the carpet.’

Humour so heavy, my shoulders sagged. ‘I shouldn’t have been there.’

‘You shouldn’t have been so easy to find. Still, I was discourteous.’

What was his voice? Not American, not quite English. Some particular tone and diction, achieved through long scowling.

He didn’t say come with me. He moved and I followed. Leaving the gallery, we passed biography stuff: photographs and letters, slideshow memories. Video loops of an overweight man who never missed a White Angel. Who, way down the line, got fat books written about him.

The Man swiped me a glance. ‘Guess you want coffee.’

It felt okay to go off with him. I mean, he was my neighbour.

Nothing chainstore, he shipped me along Orange Street to this real Italian coffee place in a tiny hidden road. The waitresses had event-horizon hair no light could escape, and eyes to make you steal papa’s hunting knife, kill a rival in some sweaty brawl, and take ship down the coast. The place served liquor.

We got seated by a beauty queen who flicked her hair, while catching a menu, while busting the meanest wiggle. I touched nothing on the table. I was scared to go near the table. I kept wholly still, pretending I looked happily young for my age. It was my parents’ fault. If they’d brought me up right, I’d have finesse pre-loaded.

He batted the menu aside. ‘Double-espresso. Ice water.’ His very sharp eyes hit mine.

‘Same. Please.’ Damn, shouldn’t say please. Shows weakness.

‘Due doppio espresso. Acqua con ghiaccio.’ Her voice a machine gun, her departure stiletto-sharp.

He manoeuvred the Rothko catalogue between oil jars that got stuff growing in them. ‘That’s yours.’

‘You sure?’

‘You don’t want it?’

‘I mean,’ I fussed the cover. ‘You bought it.’

‘I read it. He dies in the end.’ To underline the transaction was over, he checked his phone—a high-end job, not the type that comes free with a TV package.

I checked mine. Girls I knew then were real busy. I messaged that Rothko was great, said I’d post a review. Maybe some signal snafu stopped people responding. As he ignored me, I gently opened the catalogue, holding its edges two-fisted so it wouldn’t crash and spill. Every picture sharp-rendered on weighty paper, skimmed around with weighty words about cyan and suicide. Shots of the Chapel, his studios, his kids, and some haters.

I learned early that I’m nothing. Not a textbook lesson, oh no. My school was keen for us paycheques to reach fruition, to claim our place in the sorority of good choices. We got told daily—me, more often—how each of us would blossom our own unique, predictable way. It was plain to me—reviewing my grades, discarding work too poor to complete—how I was the rich guy’s kid who’d be nothing. Bumming around, never having to bother, when the end of each month daddy’s cash would show in the bank. He’d never cut me off, not through any sense of love—he never had that—just because he was public and scrutinised and needy to do the right thing.

People I met since, in these years when I been kinda busy, seem to me to be mourning their younger selves. Checking old footage, trailing old friends, not grasping that you can’t bottle a teenage crush. When I think about me sitting there with The Man, I feel no sense of chances wasted. Really, I lost nothing by what happened, for all that life’s been a testy road trip.

At the waitress’s scratchy, ‘Scusi,’ I thumped the catalogue onto my knees while she fussed glasses and cups, arranging and rearranging. He slugged his coffee and signalled a refill. I took a lipstick pass at mine and damn near choked.

He stared, no doubt seeing me as embarrassing. ‘How long you in town?’

‘Couple days.’ Like my voice just broke.

‘That’s what the water’s for. You drink the water. You here alone?’

What I recall, this real acute fear that he’d out me as a child. To say that was worse than to say I look a bit brunette sometimes. ‘Mostly by myself.’

‘You’re here with your folks.’

There wasn’t a rising inflection so I didn’t answer.

‘More coffee?’

Part of me not so evolved as the rest wanted to try the cake. It’s true, though, that cool kids eat only air—man, life on the road teaches you poverty chic—so I bulked with water and the heavy crude that place called espresso. A sleepless night, a day on my feet, Rothko—yet that coffee cleared my static quick as good speed. Coming alive, buzzing, I scattergunned words. ‘Yeah, I see my folks. I mean, see them. We came here together. But really they’re not in my face at all. They say Riz…’

‘Riz?’

‘Huh?’

‘That your name?’

‘Yeah. And you’re…?’

‘Staying all week.’ He set his water glass between the fussy oil steeps. ‘So I’ll see you around.’ His wallet so totally French leather, and the note he slung mythically large. ‘You can owe me the change.’

Already halfway to the door, so I had to yell behind him, ‘See ya,’ like some scrape.

At the next table, a classy size zero sat alone—which you never saw in my town—sipping herb tea with an actual liqueur—which you never saw fifty miles of my town. I thought I’d score a liqueur, till the waitress scowled so nasty, I gave up and inched to the paydesk, displaying the kind of physical caution you see in a minefield. After I scooped the change into my pocket, her hiss made me haul it back out to leave a tip. She said something Italian, the gist of which I got from the spit off her teeth. Outside, boys were lean and girls were shining. I yanked my stomach tight and flowed into the city.

Trusting my shoes to Wardour Street, I headed into the knotty alleys of Soho, buildings pinched so tight they nudged each other to whisper, ‘Who’s that strange girl?’ Windows gaped, spilling sounds of hunger, endurance, and love. A girl stripped to lingerie stretched from an attic window, laying her dress to dry on a neighbour’s roof. I looked and looked away. My phone rang. I knew who it was. But turned back just the same.

Caffeine kept me alive for the ride, yet the second I left the Tube’s fathomless echoes, the usual weight pressed my skull. Not improved by lines of cops and fenced off walkways that channelled me, inevitably, to bad news. Joy emptied from my squabbling head. It felt no surprise that Detective Abaid waited outside the hotel doors, pretending to check her phone. Ten thousand people saw me, any one could have tipped her the word.

‘Hey, Amelia.’

I literally froze at that awful name.

‘How’s it going?’

Factually, I had no fight with her. She was doing a tough job, I guess, and as I was not-quite a civilian perhaps it was downtime for her to chew the fat. I thought she’d give up and talk to someone more important. But those clear, brown eyes kept at me. ‘I suppose it’s boring for you. All these men,’ she grimaced, ‘making speeches. Bores me too.’

I picked up that wasn’t a confession. It was a lie to simulate friendship. There was nothing really wrong with her. She didn’t wear a wedding ring.

‘Still, at least you can go shopping. You been shopping? Sightseeing?’

‘I been to Rothko.’ As if just suddenly I remembered the half ton of paper filling my hand, I hoisted the catalogue, almost expecting some rooftop marksman to take it out for practice.

‘Rothko?’ She scanned her cultural references. ‘The painter?’

‘Kinda. There’s a big show of his. Retrospective.’

‘You like art?’

‘Rothko.’

Really, I’m not sure what happened—I had the catalogue, I showed it her, and then the catalogue was in her hand. I think our hands did some dance while our eyes were busy.

She thumbed the slab of printed matter, making slight noise at its heft. ‘It cost how much?’

‘They’re expensive. Catalogues. The ink I guess. And permissions. It’s the permissions.’

If her laugh rang false it’s because she wasn’t born to laughter. A laugh that says, ‘I’m trying to make this easy’.

‘You must drive a hard deal with your pocket money.’

Which is to say, ‘Your Dad’s minted, and I’m on salary’. Truly, dumbo here, I could have shrugged it off. Said, ‘yeah, I blew my cash for the year’, or ‘yeah, Dad buys me anything so I won’t tell about that time in the shed’. You know, or just said nothing. Me and smart, we’re not amigas. So I say to this charming, well-dressed, terrifying cop, ‘I didn’t buy it. It’s a present.’

Click and blammo. Her eyes, a vivid gleam of detection. ‘From your parents?’

She threw me that lifeline, knowing I wouldn’t catch it. ‘No, the guy next door.’

A tiny peek of her tongue. ‘Your neighbour’s into art?’

Still, still, I didn’t bail, not with sweat running down my arms, not with my shirt stuck to my stomach. ‘The guy here. I met him at the gallery. He’d done with the catalogue and gave it me.’

Sure there were helicopters overhead, cops joking each other, raw noise. Through that, a thread of fine silence. Salwa Abaid, sizing up what to do. ‘You know,’ her words rushed with sudden warmth, ‘I really don’t know Rothko. I’m not familiar with him at all. Would you mind if I borrow this? Just for tonight. I’m keen to know what I’m missing.’

Definitively, that catalogue The Man gave me came into her possession, carefully held by its edges, passed with equal care to an officer summoned by her look. The catalogue, gone from me. Maybe I could have said, ‘Don’t cops need a warrant?’ So what if they do?

In that discreet, empowered busyness of the lobby was the place to find Mum lurking. She sharpened her lipstick specially. We could have done it upstairs, away from the hired help. But it was never her style to give me dignity.

‘Where have you been?’

‘Rothko.’ Without the catalogue, spreading my hands just made me sorry-arsed.

‘You’ve been gone the whole day. Did you switch off your phone?’

‘Bad signal. Metal sculptures and stuff.’ By then, the punch of getting waylaid morphed into sticky awareness that receptionist chicks, the maître d’, the cops, all the badges were watching. And it was hours since I peed and that was distracting. ‘I think we should…’ I wanted to say, ‘Go somewhere to smash your face’, but she had the lines and leisure time to rehearse.

‘You’re fifteen. Do you know this city? Do you know what districts are safe? I’ve got to watch for you, remember.’

‘No you don’t.’ Back in the affluent, nowhere town I lived then, I might just have let her rant—mortified, sure, but no one real would see. But in London, with bigtime people around. Maybe what I said wasn’t precisely conciliatory. ‘You don’t have to watch for me. You don’t care about me. You care about earrings. You care about neighbourhood meetings to swank your new hair. You care everyone gets to listen to you. What parts are safe? The parts you’re not.’ And most pleased at getting that down without flubbing a word, I moved forward to cuff her shoulder and swish upstairs. Would have been swell if it happened.

Shockingly, she grabbed my arm, for the whole lobby to see. Her silence held the heat of a life burned up with arrangements. That second, I knew she hated me good. ‘Pack your things. Your Father’s got your room.’

The one thing she had power to do: drag me back to her so-called family. Dad would get my towering suite. I’d bunk on the rug. Dad would get my city sky and The Man for his cheery neighbour. No way. How to explain it? No way. Couldn’t reason with her—easier to reason with cops. All I had was all I hated: the sorrowful little girl from when I was too young to know better. ‘You can’t, Mum.’ I called her Mum, Christ sake. ‘Think about it: when we got here, how the kids were with Dad. They can’t remember going places with him.’ Because the waster was never home. ‘They clung on his legs when we had to switch rooms. Right here, they made all that rumpus. They’ll be in the lift all hours to see him.’ And I hate the brats and they hate me. ‘They’ll be whiney. Just like at home.’ I was whiney myself. In the real life of that family, only gross submission got play.

Through the heat of her hate for me, she understood how my punishment let Dad off the hook yet again. Those suites were palatial for one ginger girl; a tight fit with two antsy hellspawn. When Dad got back from the conference each night, he was trapped—that was the novelty. ‘Maybe it’s better,’ her voice like nettles. ‘This way I don’t have to smell you.’

3