9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

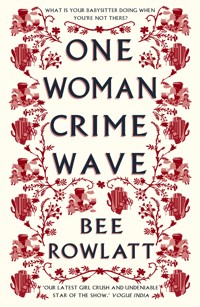

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

What is your babysitter doing when you're not there? Fifteen-year-old Ashleigh is clever and charming, all too ready to rush to the rescue of parents in need of relief, and she soon becomes the neighbourhood's favourite babysitter. But she has an appetite for secrets. Fast-paced, witty and scalpel-sharp, One Woman Crime Wave examines the limits of what money can buy, and how easily the fragile web of middle-class privilege can be torn. In the end, is it really Ashleigh who's the problem, or is it the fractious and divided community she exposes?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

OneWoman Crime wave

bee rowlatt

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

One Woman Crime Wave first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2024

Text © Bee Rowlatt, 2024

Quotation on p. 9 © Priestley, J.B., An Inspector Calls, 1993. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education Limited

Cover design by Will Dady

Bee Rowlatt asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental, or is used fictitiously.

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

one woman crime wave

‘Dad, if you call the police you will never see me again.’

He walked past McDonalds and the smells poured out, eggs and coffee, simple smells. Ludi remembered smells like something from before. Normally he’d be straight in there for an Egg McMuffin but now his stomach heaved. He was walking forwards but pacing back in his mind. Back to last week when his life was just a life. Back five years when she was still a child. His child. Back to today, just this morning, when they found her. In that – whatever that place was, a loony bin. A crazy weird pile of madness with his own daughter at the middle of it all.

Christ almighty, with his own eyes. And that Tara woman going I will make her pay, I will make her pay! It pulled open the wounds. He tried to think back. Was there a link, from this, from now, to back then, to earlier? It hurt too much to go back into the memories. Ludi shook his head. He didn’t want to, it still hurt. But now he needed to understand Ashleigh. His own daughter, just this morning, right to his face. ‘Dad, if you call the police you will never see me again.’

His mind shook. He had called her phone again and again, first raging then in fear. Where was she now? He thought of those missing child stories on the news, and a memory came, Ashleigh’s first school photo. There was nobody to give the extra copies to, they never had no one. But still bought the most expensive set: multiple photos in every size. The whole flat covered in different-sized Ashleighs, all smiling away with her gappy teeth. It’s those photos they show on telly when a kid goes missing.

His mouth dried up and felt like his voice had disappeared, he hummed to see if it was still there. The hum died in his throat. He walked by the neon poster on the bus stop, Olympics logo – it was everywhere. A City Like No Other. No shit. Fifty nationalities, the home of the avant-garde and high finance. This was his home too. This same old road, straight out of the heart of old London. He’d pushed the buggy round these streets, and done countless call outs. Streets that had once been fields, where other men trudged, with other fears that no one knew about.

Where was she? Ludi turned off and took a side road, the other way round over the railway bridge where him and the kids used to watch the trains. The hedges were growing out into the pavement, he let them catch his face. There was the bridge, the sign with the emergency number in case of a crash. Who did you call if your life crashed. There was the usual graffiti and above it in giant letters one painted word HOPE. He’d never really looked at it before.

Hope. The wind pushed a crisp packet along the gutter. He thought he knew his daughter. Then today found out he didn’t. That was the worst. And now he was walking around half destroyed and wearing a jacket stuffed with cash. So maybe this was the worst. Maybe this was a whole new worst, only just beginning.

PART ONE

‘If we were all responsible for everything that happened to everyone we’d had anything to do with, it would be very awkward, wouldn’t it?’

j.b. priestley

1

ashleigh arrives

Ashleigh pushed the doorbell and took a quick step back. She stood straight and looked up at the front of the house and the upstairs windows. It was the same house. But not the same. A small front garden with tidy hedges, like a house in an advert. She had never been back. She looked away from the rocking horse in the front window – she didn’t want to be peering in when they answered. Guess who’s back, she murmured. She took a breath, prepared a minimal smile and looked directly at the centre of the door.

‘Hi I’m Tara, and you must be the famous Ashleigh,’ Tara smiled widely as she pulled the door all the way open and they looked at each other for a second.

‘Come on in!’

‘Hi – thanks,’ Ashleigh moved past her into the house and felt Tara’s eyes skim down and up as she went. Ashleigh had crafted the Perfect Babysitter look: pink sweatshirt and nice jeans, no make-up. Her straight blonde hair was in a loose bun with strands hanging out and she was carrying a school bag on her back.

‘Great! Please, take a seat! Make yourself comfortable!’

Ashleigh slipped the bag off as they came to the table, balancing it on her lap as they both sat down.

‘I’m told you’re the number-one babysitter in the neighbourhood!’ Tara’s voice was full of exclamation marks and her eyes and mouth were big.

Ashleigh laughed politely. ‘Thanks, it’s all through school. I’m at Selby High now but my little sister Morgan still goes there, she’s in Year Five.’

‘OK!’

‘So, what year is Betsy in?’

‘Betsy’s seven now, she’s in Year Two.’ Tara began describing Betsy’s routine. It sounded like she’d covered this a hundred times: sleep regimes, special toys, favourite songs and books, rules on food. Ashleigh nodded thoughtfully, maintaining eye contact.

‘She has to have her toys arranged in a special way before she can sleep, just one of those funny things!’ Tara stood up as she carried on talking, and dabbed some Touche Éclat under her eyes in the mirror. ‘Giles is already putting her down though,’ she said. ‘She’s a good sleeper so you won’t have any trouble.’

‘Ah OK, that’s nice.’

‘And it’s great that you live so close by. Our nanny Samina wasn’t free tonight. She’s wonderful but you know – it helps to have backup!’ Tara scrabbled in her make-up bag and there was a comfortable pause. ‘Do you do school pickups?’

‘Yes, I used to collect Morgan but now she does football until Dad gets her, so I’m free most evenings.’

‘Good to know! I work in TV,’ Tara added breezily, ‘but I’ve recently started writing, I’m working on a screenplay so I often need some extra help.’

‘Oh that’s so cool!’

Tara smiled as she leant towards the mirror, checked her teeth and shook her hair out of its ponytail. ‘And you live in the blocks, just over…?’

‘Yes I live in Tanghall,’ Ashleigh said, and let the slight pause hang there. Everyone knew those blocks. Ashleigh caught the raised eyebrow in the mirror and the ‘haven’t you done well’ look. She couldn’t help herself: ‘I used to live here, though!’ she said, immediately surprised by having let it out. Ashleigh never usually shared stuff, let alone something like this.

‘Excuse me?’ Tara was finishing her eyeliner. The fridge buzzed, there was a sound of footsteps upstairs. Ashleigh glanced away, through to the French windows leading out of the kitchen.

‘I used to live here,’ she went on, ‘when this house was flats. We lived upstairs. Before we moved out, it was about five, six years ago?’

‘Here, really?’ Tara frowned slightly. ‘Well isn’t that funny. This must be a trip down memory lane for you.’ She added one last flick of mascara and blinked at herself in the mirror.

Giles came rumbling down the stairs and into the room, wearing beaten-up Converse, jeans and a hoody.

‘She’s down at last. Just listening to the CD. Oh, hello!’

His eyes took Ashleigh in with the thrill of enjoying, up close, that sly fresh teenage beauty. When his gaze reached her face she raised her chin very slightly. He looked away and adjusted his watch strap.

‘Yes, this is Ashleigh and she used to live here – isn’t that sweet,’ said Tara, pushing the chair back as she stood up. ‘Come on, let’s get going or we’ll be late. Have you got the car keys?’

A few more goodbyes, then the front door closed and they walked away. Ashleigh listened, tracking the sounds as they left. Finally that was it – they were gone. And there she was, sitting at the kitchen table. They’d been super-friendly. They’d done the cool parent thing of pretending to be on Ashleigh’s side: ‘Kids eh, they’re a nightmare haha.’ And she had done the sensible babysitter thing, and looked them straight in the eye, calm.

She always brought her school bag along, filled with books. They loved that, the parents. And she made sure to include science or maths books, because they also loved saying ‘Oh, I was terrible at that. Let’s have a look, wow, I could never do that. Isn’t it cool how girls are doing these subjects nowadays!’ and they’d laugh. And Ashleigh would smile modestly. And she’d think – just wait till you get out that door.

She drummed her fingers and then her fingernails on the oak table. A brand new place. And this was not just any place. This would be special, better than the rest. She shut her eyes. This was the best part. When the parents left, here’s how it went. First, she spread out her books and pencil case. She opened a page and made a few notes. This should take at least ten minutes because parents generally came crashing back through the door – ‘I forgot my keys/phone/wallet’ – and there she’d be, phone face-down and pencil poised. Everyone’s favourite A-starred angel.

Ashleigh checked the time on her phone. Ten minutes was usually about right. Today she would make herself wait for more than fifteen though. It made it more exciting. She hummed quietly. She’d discovered there was even a name for it: ‘deferred gratification’. A delicious name, she thought. Kind of a strong name.

The other thing parents did was send a text once they were on their way. Basically so they didn’t feel guilty about leaving their kids with a complete stranger. It helped them feel like they were still in control. It usually went something like If he wakes up – spare milk in fridge :-) back around 11. And Ashleigh would always send a prompt and reassuring reply. And then came that surge of the most powerful joy.

Because they were not in control.

2

tara arrives

Tara was unusually perky in the car on the way to the dinner party. The other mums were right, she told Giles, this was no ordinary babysitter.

‘I mean, the gold hoop earrings are a bit councily, but no accent at all, nothing to rub off on Betsy – not like that au pair with the cheap perfume!’

And they laughed. Giles swept his hands confidently on the steering wheel as they turned into a street full of tall white stucco London houses with massive bay windows.

‘Aha – the perfect space!’ Giles began to reverse into a parking spot. ‘What did you mean she used to live in our house though?’

‘It must’ve been that upstairs tenant who delayed the sale for ages, remember? Oh god, and that old carpet,’ Tara said.

‘The rhapsody in brown!’ said Giles, and they laughed again. They had moved in seven months later when it was all knocked through.

‘OK, here we are.’

Tara felt dwarfed by the wide steps leading up to the front door. Inside they hugged and cheek-kissed the hosts, and Tara caught sight of herself in the hall mirror. Her chestnut base with balayage chocolate lowlights gleamed in the halogens. She took a breath and felt good again as they were led downstairs. The dinner party was with some of Giles’ old friends from university. They had less interesting jobs than him but much bigger houses, she noted, then smiled her confident smile and scanned the row of faces.

They were sitting along a long oak table with masses of tealights down the middle, in a huge basement kitchen with a wine wall.

‘Oh yes – lovely, elderflower fizz please,’ Tara accepted a glass and laughed. ‘I’m the boring one tonight as it’s my turn to drive!’ As she sat down Tara could see the conversations were already beginning to self-select by gender. She was in sub-prime seating towards the end of the table, with the hosts at the other end. Which was worse: lumping all the men together to bray over each other, or alternating them between buffers of sacrificial women to soak up the shoutiness? She could shout just as well as them, but she was tired, and the lack of wine didn’t help.

She gulped in preparation for someone asking about her job. The truth was that since having a baby, the world of TV had closed behind her and pulled down the shutters. She had agonised over whether to add the word ‘Mum’ to her online profile. Maybe it could unlock access to a working-mum elite. Those ninja-mothers probably didn’t boast about being mums though, they were too busy succeeding: ‘What – these? Oh they’re just some gifted children I popped out between award-winning documentaries. But you’d never know from these abs of steel haha!’

Tara adjusted her ponytail. It wasn’t just work – it was the social life that came with it that she craved. She used to be the life and soul. And Betsy was seven years old now but Tara still hadn’t regained her party mojo. If anything, it was getting harder. She looked around again, she wasn’t near anyone she knew. Giles was up there, three people away. Far enough for her not to be able to join in, but close enough to hear his voice. Look at him, tipping his chair away from the table and stretching his arms out wide. He ran his fingers through his hair. It was messed up to look like someone who didn’t care. She knew exactly how much he cared.

She tried to block out the familiar opening lines about his newspaper column.

‘Oldest trick in the book,’ he was saying. ‘Fillet everyone for all the copy you can get, but make sure to give your sharpest putdowns to the wife. That way everyone looks good, isn’t that right, Tara,’ he shouted down to her. She smiled indulgently and looked down at the Ottolenghi shakshuka and jewel-coloured salads on her plate.

‘Yeah, bloody funny,’ chimed a guy who worked in private equity.

‘We’ve all been there,’ the man on Giles’ other side spoke over him. ‘You know the competing parents, that school-rage thing you wrote about…’

‘Oh that,’ Giles rotated like a lighthouse. ‘But things have changed. I went to state school’ – he paused to let that soak in – ‘but these days even that’s not enough. Anti-privilege has gone so far the only way to compete is to have had a childhood straight out of the Monty Python four Yorkshiremen sketch.’

The private equity man tried again: ‘Eeh, we dreamt of a cardboard box.’

Tara considered his determined pink face and wondered whether a banker would have been a better life partner. They’re never there, for starters. Look at him; she thought, conversational antimatter, but probably even his job ranks above being a mum who once worked in TV. She brought her gaze back to the people closer by. She straightened her back and put on an active listening expression, curious yet unjudging, like a therapist.

A pointy woman with baked-looking blonde hair projected in: ‘The way it’s going the only way into Oxbridge will be to have a disadvantage, never mind top grades – they’ll need some kind of mental health problem, or be, you know, ethnic.’ It was the same conversation taking place, in stereo, to either side of her. Tara sighed, and like a weary tennis spectator returned her gaze from the blonde woman back to Giles’ persevering neighbours.

‘I for one am sick of being expected to apologise for having gone to a decent school—’

‘We’re rolling out inclusive recruitment but I keep saying: I just want the best person for the job.’

With a sudden light feeling Tara realised she could throw the same line in both directions at once. She took a sip from her glass, looked both ways and cleared her throat, ‘If you add up everyone who’s a minority then surely we’re the endangered ones!’

No. It didn’t work – no one heard. The flows continued uninterrupted around her. She stared down at the empty fork in her hand, orphaned in the middle without a claim on either conversation. She picked out a pomegranate seed, chewed it slowly. Wasn’t that the food of the underworld? She began to eat her way round the edge of an egg yolk, keeping it intact. Ottolenghi and competitive fury, that’s what we enjoy while paying someone else to sit in our house. She reached over and took an olive from a carved wooden dish.

No one had asked about her work. In theory she could still say she worked in television, even though it was only development. Plus the volunteering for No Cuts, the anti-FGM campaign. They came to give an awareness event in school and in the resultant indignation Tara had offered to help out by writing a blog. Female genital mutilation – can you believe these people! Right here in London too, and more common than anyone knows. Cutting little girls only slightly older than Betsy!

She wriggled the olive stone out the side of her mouth but there was nowhere to put it. Her blog had got over two thousand shares though, people were taking notice. But it wasn’t enough. The truth was that her professional muscles had atrophied away in a sea of mums’ lattes, and no amount of yoga could fix that. So now she was trying to develop the blog into the beginnings of a screenplay. ‘How’s the “work of art” coming along,’ Giles would ask, using actual sarcastic fingers, whenever he saw her on social media.

She put the olive stone on the side of her plate and looked up the table. There he was, three seats along. He drew energy from around him like a flat iPhone brightening into life, charging up from the duller glows on every side. Tara slumped slightly as she became an audience member. Giles was extolling Avenue Road Primary, their local state school, and its melting-pot diversity. All mixed up together like bees in a hive – adorable. But secondary school, no way. Then it had to be private, this way you got the best of both.

Tara had no desire to take part in this exchange. She knew that once people started talking about schools then the tutoring conversation wasn’t far behind. It set off a small glow of panic inside her that she and Giles still hadn’t solved the problem of Betsy.

‘Actually,’ the guy next to Giles butted in, ‘our neighbours did it the other way round – they sent their girl to state school at the end, for her A levels, and that way she got a lower offer from Durham!’

Right on cue someone mentioned a tutoring service that was tailor-made to make your child appear untutored, because apparently Oxbridge could now spot that a mile off: ‘This way they come over as smart but in a raw, original way.’

‘Whatever it takes – but my point is,’ Giles allowed a theatrical pause, ‘diversity’s all very well but, you know – I don’t want dealers at the school gate.’ Another pause. ‘Unless I can get my hands on some of the stash too HAHA!’

This rolled all the way down the table on a wave of delighted outrage, sparking a happy consensus that private schools were awash with drugs too, but at least they were likely to be of a better quality. The baked-blonde woman looked over with a ‘isn’t your husband naughty’ smile, and Tara gave a half smile back.

Why hadn’t anyone asked about her work? Didn’t she even look like someone with a job? She realised she was biting the insides of her cheeks so she tried a calming breath. Out of nowhere her eyes suddenly filled with tears, the candles along the table blurred into a bright mess. She remembered her mindfulness app: look at the pebble, imagine its touch. She’d forgotten to do the pebble today. Her stomach bubbled and made a mournful noise like whale song.

She glanced back at Giles, watched him shake a salad leaf off his fork before restacking it and filling his open mouth. She recalled seeing him through the bathroom door that morning, shaking drops off his penis. Like taking the petrol pump out of the car. She looked away again, returning to the guy on her other side. On the way she prayed her silent dinner party prayer: Please don’t talk about schools – I’ll do anything, even house prices, but please please not schools…

‘So we’re pretty delighted,’ her neighbour beamed. ‘Our oldest just got a scholarship!’

3

ashleigh explores

Ashleigh stood up and took a deep breath. She quietly replaced the chair under the table and walked to the fridge. She stood and looked. The usual layers of school letters and babyish drawings covered its door. That’s what they want everyone to see. It’s what’s behind that counts. The huge silver door swung back. Here we go, as easy as if they’d left their bank statements open on the table. She was guessing M&S ready meals, farmer’s market stuff, no Tesco and definitely no Supervalu.

Woah, but these guys. Two bottles of champagne, not Prosecco. Ready-picked pomegranate seeds like a bowl of rubies, and fresh herbs. Italian water. Brown mushrooms in a cardboard tray. Soya milk. Greek yoghurt with Greek writing on, and different coloured olives in a jar. Some butter that wasn’t from a supermarket. She used to like the big brands but now she knew that not having any brand at all was even posher. No ready meals – not even in the freezer. There was a weird-looking cheese wrapped in paper inside the door. She sniffed it and put it back.

Ashleigh always started with the kitchen, inch by inch, shelf by shelf. She examined everything they ate, she assessed and catalogued each discovery, careful to note and memorise anything unfamiliar. She had trained herself to take her time, steadily, turning items over, unwrapping, looking behind, seeing every angle. She would eventually move on to each and every thing they stored. But she started here with the daily stuff: fresh foods, snacks and breakfast.

Breakfast was gross: grey oats, dusty muesli. But apart from breakfast, everything was better for rich people. Even their sugar. Who knew that sugar could be so different. She took a pinch and spread it out on the marble counter. Like grains of sand from a tropical beach – each particle was irregular, distinct. Bigger than normal sugar. She separated out one crystal, rolled it between her finger and thumb, then licked it. It tasted golden, almost smoky. She swept the leftover grains into her pencil case. She would compare them to the stuff her dad loaded into his mugs of tea.

She liked moving things around and she’d notice herself remembering how to set everything back precisely afterwards. Sometimes she’d even do a few different moves in a row to test herself. Then she’d have to do them backwards and in reverse order. She’d stand on a chair or even climb along the kitchen surfaces, reaching up for the high shelves. She could recite the geometry of her moves and climbs. And the higher she reached, the more unlikely the discoveries.

To date, her top-shelf favourites were a tin of tongue – tongue! – four years out of date, and a packet of lentils. The lentils on their own weren’t interesting until you compared them to what was in the fridge. Like she’d learnt in history: context was everything. When you looked in their fridge and saw only a stack of mid-range ready meals, then you knew for sure this unopened lentil tragedy was some kind of promise gone wrong. They would never see the light of day. Every time she babysat at Charlotte’s place she revisited them, the lentils of lost dreams, to enjoy the failure.

Yes the backs of the cupboards revealed as much if not more than the fridge. They showed the hidden hopes. Back here was where she found the context, the deeper history. Mr Stokes would love this – she wished she could do an essay about it. He was the best teacher. Today they did fascism and its distinguishing features including scapegoats, propaganda, and the refusal to tolerate free inquiry. Ashleigh collected phrases like this, repeating them inside her head. Then later she’d practise them out loud when she was alone:

‘But surely its distinguishing feature is its refusal to tolerate free inquiry?’

I’ll give you a free inquiry, she laughed quietly. She reached up higher. These shelves were like a wish-list zone. Probably inspired by a TV show, foods that seemed a good idea at the time but would never happen. They were people’s more successful, healthy vision of their own lives. Unopened spices, experimental noodles, unrecognisable kitchen implements. That bag labelled Authentic Organic Chapatti Flour. As if.

Anyway there was nothing like that here. This was the most impressive kitchen she’d ever done. The cupboards weren’t messy or piled high, they were organised. More than organised, they were – what was the word? Curated. It was more like those shops around Bond Street, the kind so fancy they hardly sell anything. Like one pair of shoes in a single spotlight. No top-shelf shame round here.

Le Creuset. Bitossi. Liberty London. And their cups were all small. No supersized mugs with slogans or cartoons on. None of that. She would keep looking. Everyone has something to hide, and she always kept going until she found it. Higher shelves were the obvious place where parents stashed their treats. Mostly biscuits and crisps, and usually behind big things like pasta or flour. One day she’d alert the children she babysat to this deception. The ‘unacceptable’ booze also lived up here. Cheap quarter-bottles of whiskey and vodka from Londis, next to boxes of instant cake: simply add one egg.

Once she had uncovered a priceless trove. It was one of her other homes – Stacey’s kids. A regular Weetabix box, but by chance she squeezed it, and it felt wrong. Inside was a folded-over bag pushed deep down. Froot Loops with Marshmallows. With a rush of delight Ashleigh realised that Stacey probably had an eating disorder, and sure enough she eventually found, in the bottom of the lowest fridge department, inside a salad bag with another salad bag on top, a giant Galaxy bar. It had actual teeth marks in it. She uncovered facts, checked her theories and proved them, growing her knowledge of their lives. Houses and flats, posh and normal. Certain truths applied everywhere, that was the best part. They all wanted to show some things and hide others.

This kitchen was the back half of a much larger knocked-through room, with the fireplace, the TV and the sofa, the desk with a computer and a monitor screen. There was a tall lamp at the side of two framed paintings that really were paintings and not photos of a painting. She picked up a stack of papers lying on top of the printer and flicked through: maths pages and word searches, a few school letters. She ran a finger over the controls. She always had to print out her own work at school or in the library.

The shelves were bookended by shiny houseplants. Ashleigh touched a leaf, admiring its high gloss. She poked the soil to see if it was fake. It wasn’t. Once she’d had her own plant, a tiny rosebush from the garage shop. It lived on the kitchen windowsill in their flat. One day she saw a couple of greenflies. The next time she looked the bush was covered, smothered by tiny creatures. Her dad swore and threw the whole thing in the rubbish. But Ashleigh didn’t hate them. They hadn’t missed a single leaf, stem or bud. That was how to do it. Thorough.

From here in the kitchen heartlands she would move outwards, uncovering every secret, every intimate area of the home, expanding. She knew more than they did. It gave her a towering feeling that grew each time, it got better and better, and so did she. Sometimes she could feel her own pulse. Ashleigh was proud not to miss one centimetre of any of the homes she worked in. She always found what she wanted, in the end.

4

tara endures

‘Are the Olympics too expensive? Maybe,’ Giles paused, ‘but I’m not complaining about the ladies’ beach volleyball!’

The woman whose house this was moved around the table, reaching between people to gather up the plates. None of the men helped, Tara noticed, and she was about to offer when she realised it was patriarchal and decided against.

‘No one fancies skinny women, you know,’ Giles went on. ‘Isn’t the ultimate triumph of feminism that women starve themselves not to please men but to please each other?’

There was a ripple of nervous laughter and several bony women at the table avoided each other’s gaze. Tara looked away from him.

‘But seriously, women are taking over now – and about time too. My boss is a woman. At work and at home haha.’ He raised his glass. ‘I’m a feminist too. Here’s to women!’

She tuned back into the blonde woman’s monologue, which continued without hesitation as the creamy lime and coconut syllabubs landed, concluding:

‘I saw this thing on Indian street children and the caste system – it was simply unbearable, the way they treat them. I just feel like, having kids, as a mum, it literally connects us to the world, it makes me care more, you know?’

‘I don’t agree,’ Tara finally got a word in, her face ached with the strain of passive listening.

‘Having kids makes you care about your own kids. Not other people’s! And as for caste systems, well, our country is run by Etonians, so…?’

Tara saw one of the woman’s eyes flinch – clearly this was someone with a centuries-long connection to Eton.

‘Wow,’ she continued less emphatically. ‘Did she say this syllabub was vegan?’

They both looked away. Tara sat back again. It would be less effort just to allow the evening to wash over her.

The mood of the table took a sudden turn for the optimistic. It was agreed that the era of ‘isms’ was finally over; for all people kept going on about social mobility it was clear that humans had basically cracked it. Even disabled people had got their own Olympics, and why not, it was the best time to be alive, and the best place too. Never mind Great Britain, this was Great London!

Giles then launched into the UK Independence Party clowns – they’d put the wrong name on their mayoral ballot papers, ‘But their leader blamed the voters, saying they didn’t understand – how never to get another vote again!’

‘He’s on the news all the time, though, so someone must like him!’

‘Only morons. And northerners,’ Giles boomed. ‘It’s nothing more than a suburban nostalgia kick, a blast from the past.’

Such conviction – it was so solid and dependable, Tara admired it in a way. She remembered that dinner where Giles sat near someone from Thailand, and explained that nation’s politics to her on the basis of his holiday there six years earlier. It wasn’t the information itself but the sharing of it that seemed to give him such a hard-on. She sighed and looked around. The blonde woman had now co-opted someone else and was laughing hard.

She refilled her glass with water this time, she’d finished the elderflower fizz. She turned and caught the eye of the man on her other side. She smiled generously and he introduced himself as Alex, a lawyer. He was in the middle of a story about the time the Australian government flew him in to advise on tax reform. He pushed back from the table to include her, expanding as he spoke. She couldn’t tell whether she was supposed to be pleased or appalled by the story so she looked at his torso and imagined him reaching orgasm. The thought coincided with her last spoonful of the watery bit at the bottom of the syllabub. She frowned.

Alex the lawyer carried on talking. He was now this end of the table’s counterweight to Giles. What did these men do when there weren’t any women to listen to them, she wondered. She eyed his shoes, they were the slip-on kind, with a golden buckle! Who wears those? Probably Berlusconi. And men who pay for sex. He went on to broadcast a series of unrelated facts such as aphids contain their own grandchildren, and his father was 100% self-made. Tara’s face continued to smile while she pondered the lack of names for men who pay for sex, when there are so many for women who sell it.

The topic of childcare moved down from the other end of the table, providing a welcome change of voices as well as a showcase for open-mindedness. Someone mentioned their nanny who was ‘from Africa’. This was teaching the children not to be racist, ‘But our cleaner’s Latvian and she is racist, which is crazy really!’ This was instantly bested by someone who had a ‘manny, a male nanny’. Everyone stopped and tuned in.

‘We’re totally subverting gender stereotypes – men can be just as caring, and Dolly and Jess are learning to play football too.’

Everyone chuckled fondly. Giles didn’t chuckle. He couldn’t help himself: ‘We’ve got a Muzzer.’

‘A what?’

Tara shot him a warning glance. ‘A Muslim. I mean she doesn’t wear one of those scarf things but she’s a proper Muslim, her family’s actually from Iran. I mean Iraq. So when it comes to being radicalised our kids will totally have the edge: Allahu Akbar!’

It was a joke too far, Tara felt, but there was definitely something off about her. She leant an elbow on the table, pondering the subject of their nanny Samina. She was too chatty. And what about that time Tara jokingly said, ‘Oh god, there’s so much booze in the fridge – what must you think of us?’ And she had simply agreed: ‘Yes, it is a lot.’ And Tara’s laughter had been left hanging. Ever since then, Tara had felt judged. By her own nanny!

In any case they’d recently talked about Samina being too expensive. Tara ate a cantuccio biscuit, hearing the crunching and grinding inside her own head. Coffee and tea came and went. She had another cantuccio biscuit. As a child she’d been taught to chew her food twenty times. She chewed slowly and purposefully, as if she was carefully considering the flavours within each bite, covering up the fact that she had no one to talk to. Alex the lawyer was deeply engrossed in the pointy blonde who was now laughing her head off.

Probably no one knew that she used to work in TV. They