10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Mark Jonnson's life is a mess. He's been cheating on his wife, fears his marriage is over, but can't bear to leave his boistrous 7-year-old daughter, Matilda. Just when he thinks things can't get worse, his mother is killed in a road accident. Shocked and grieving, he decamps to her house, where he uncovers a secret that will turn his life upside-down and send him and his daughter on a whirlwind search for the truth. Another gripping read from the author of Truth Games and Love, Revenge & Buttered Scones.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

OZ

BOBBIE DARBYSHIRE

Contents

CYCLONE

November 2008, Monday

Tueday

June 1978

2008, Friday

1978

December 2008, Wednesday

Saturday

1978

2008, Sunday

Monday

Friday

1978

2008, Monday

Christmas Day

JOURNEY

1978

2008, Saturday

1978

2008

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

New Year’s Eve

OZ

2001

January 2009, Saturday

Monday

2001

2009

1978

2009

1978

2009

1978

2009

Tuesday

2001

2009, Thursday

2001

2009

HOME

November 2009, Tuesday

Acknowledgements

Bobbie Darbyshire won the 2008 fiction prize at the National Academy of Writing and the New Delta Review Creative Nonfiction Prize 2010. She has worked as barmaid, mushroom picker, film extra, maths coach, cabinet minister’s private secretary, care assistant and volunteer adult-literacy teacher, as well as in social research and government policy. Bobbie hosts a writers’ group and lives in London.

Praise for Bobbie Darbyshire’s earlier books

Truth Games(Cinnamon Press, 2009)

After the hippies and before the yuppies, between the advent of The Pill and the onset of AIDS, between the ‘summer of love’ and the ‘winter of discontent’, the newest game in town was sex. In London, in the baking, dry summers of 1975 and 76, a group of friends get out of their depth in infidelity.

‘Shows the deft touch of a psychologically astute social satirist.’

‘Leaves you with that taste in the mouth: a blend of loss, innocence and cynicism.’

‘I read this novel like a hog eats its share of strawberry tart.’

Love, Revenge & Buttered Scones(Sandstone Press, 2010)

A comedy of errors with dark, serious threads, in which three troubled lives become mysteriously tangled in the Inverness public library.

‘The brilliantly plotted narrative grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go... A triumph!’

Published by Cinnamon Press

Lytchett House

13 Freeland Park

Wareham Road

Poole

Dorset

BH16 6FA

The right of Bobbie Darbyshire to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2014 Bobbie Darbyshire.

ISBN 978-1-78864-185-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

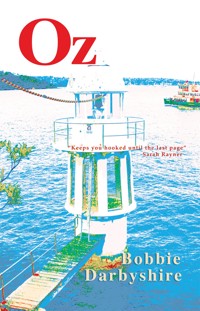

Designed and typeset iby Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Jan Fortune and Adam Craig from original artwork ‘Sydney Harbour Lighthouse’ by Ben Mcleish © agency: Dreamstime.com

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress.

This one is for Jason

CYCLONE

November 2008, Monday

By the time I’ve walked back to Clapham Junction it’s dark. A bitter wind cuts through the crowd on the platform, but that’s not why I’m shaking. I pull out my mobile and dial Hove. ‘Dad,’ I say.

‘Mark.’ His surprise crackles in my ear. ‘Nice to hear you. It’s been a—’

‘Dad, I’ve something to tell you.’

I imagine him at the window of his flat, looking out at a turbulent sea. The phone’s clamped to my cheek. ‘She’s dead,’ I say.

‘Who?’

‘Mum.’

I hear his intake of breath, but his words are drowned by the station announcement. ‘... seventeen twenty-one... calling at Vauxhall and London Waterloo.’

He wants to know how, of course. I close my eyes, breathing short, difficult breaths. It’s a joke in bad taste. My brain can’t bypass the words, so I’m blurting them out. ‘She fell under a bus.’

‘What?’ he says.

‘Whitehall. This morning. Not looking.’

‘Oh—no—’

‘St Thomas’s rang me. I went there, I saw her, and now,’ I’m choking, ‘now her house, Dad—it’s as if she’s due back any minute—’

‘I’m so sorry, Mark.’

I stall. Sorry. The word’s wrong.

I need him to protest. To tell me this isn’t happening.

‘Are you?’ I say.

‘Of course. Terribly sorry.’

For me he means, not for her. He ran out on her twenty-five years ago when I was small. The old anger surges. Useless.

‘Mark, are you all right? Where are you?’

‘On my way home. Look... Dad... Train’s here. Got to go.’

I snap the phone shut, panicking, staring around me, trying to shut out the image of Mum on the mortuary table. Not true. A mistake. As the train draws in and pulls to a halt, a child is taking me over: a lost little boy who if he weren’t shivering in this press of strangers would burst into tears. She will surely come soon and find me.

I’ve just been to her little two-up-two-down house along by the railway line, but she wasn’t there. Only last night the place was crammed with people, partying, celebrating her birthday. I’d taken along a Best of the 80s CD, and I watched her dance with her mates, more like thirty-six than fifty-six, a glass of wine in one hand, half a poppadum in the other, hair flopping in her eyes, singing along to Cyndi Lauper. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun. Two hours ago when I eased open the front door there was no music, no dancing, just a faint smell of curry. Everything was as she’d left it this morning, the CDs piled by the player in the kitchen, her scuffed trainers on the hall floor, a stack of ironing in the living room that she must have hidden out of sight for the party. Upstairs, a crumpled towel on the landing, the cap off the toothpaste, some bills and scribbled notes beside the laptop in the back-bedroom-turned-study. And then in her bedroom a nightdress, a hairbrush, a paperback face down and the sleepy old cat waking and yawning. Beside the bed were two photographs of me, one as a baby being lifted from a bath, the other taken with Gina and Matilda on Brighton beach this summer. Big smiles.

If I had touched nothing, told no one, all might still be well.

Passengers stream from the carriage, and the crowd surges forward, carrying me with it. I’m in among the winter coats, the averted eyes, the flapping Evening Standards, the ears white-wired to iPods, the mixed smells of damp people wishing themselves at home. I’m big, a head taller than most, but inside right now I’m small and scared.

For a long while I sat at the top of Mum’s stairs looking down at the mosaic of coloured floor tiles. Through the wall came sounds of kids home from school: a shriek, a laugh, a woman’s raised voice. I got to my feet and went down the stairs slowly. Stood a while in the hall, looking at Mum’s raincoat hanging on a hook.

At Waterloo I’m stumbling from the train and with the crowds down into the Tube, following the Jubilee signs, and soon I’m on another packed platform, watching another train roll up and open its doors. So many people streaming off, pushing on. Mum is surely still out here somewhere if only I knew where to look.

I’m kidding myself. She’s gone.

In her house the silence was rising like floodwater. I couldn’t breathe. I dumped the bag of her things the hospital had given me on the kitchen table and fled along the hall to the street, pulling the door shut behind me. I had to fight to get control of my face and my voice before ringing the bell next door.

The neighbour was shocked, kind, sympathetic. Of course she would have the cat. We went back and fetched him.

My feet drag as I turn into our street in Kilburn. Gina told me to pack up and get out this morning, and part of me was ready to leap at the chance. The dilemma feels blurred now, as though it concerns someone else.

The entranceway, shared with the bookie, is littered with fag ends and betting slips, and there’s the usual stink of piss and cider. Matilda hears the turn of my key and comes hurtling downstairs, so fast I’m afraid she’ll tumble. ‘Daddy! Daddy!’

‘Hi, Little.’ I sweep her up for a hug, warm and alive. Her tangled red hair smells of chlorine.

‘Daddy, I can do the doggy paddle.’ She demonstrates in my arms, twisting onto her stomach so I stagger, nearly dropping her.

‘Without wings? Without me holding you?’

She flails arms and legs. ‘I took my toes off the bottom, and Miss Barrett said I was swimming. I only swallowed a little bit, and I kept my eyes open.’

‘Good for you, Matty.’

As I set her down, she squeals with excitement, displaying the gap in her front teeth. She’s perpetually astonishing: the whole reason I stay. The red hair, the freckles, the green eyes are mine; the curls and a smatter of genteel Americanisms come from Gina.

The stairway above us hums with toxic vibes. I’m reluctant to climb, but Matilda plants her palms on the seat of my jeans and shoves me upwards. Does she know something’s wrong? Gina and I have been waiting until she’s out of earshot to hiss and whisper at each other, but she must sense the atmosphere.

‘Can I have a bicycle for Christmas?’

I’m not falling for this one. ‘Have you asked Mommy?’

My head clears the banister rail, and I’m looking into the galley kitchen, where my wife, still in the monogrammed fleece from the bookshop she works in, stands sideways on, jaw rigid, her hair scraped back in a scrunchy, savagely peeling a potato.

The wall clock shows nearly six, and I remember it’s Monday, my half-day, no afternoon class. I should have been here by two-thirty, should have made the tea. My phone’s been switched off. She probably thought that I’d left her.

I need to tell her straightaway about Mum. I’m opening my mouth to ask for a moment alone, but—

‘Santa will bring me a bicycle,’ shouts Matilda. She seizes my hand and runs around me so I rotate on the landing, turning my head like a dancer to keep looking at Gina, trying to catch her eye.

She glares at the potato. ‘She’s been at me from the minute I picked her up.’

I disentangle myself and step closer, willing her to look up.

Matilda leaps at me, knocking me off balance. ‘It’s thirty-one sleeps to Christmas!’

She’s using me now as a climbing frame. ‘Matty, please don’t. I need to talk to—’

‘Fifty-two sleeps to my birthday!’ She dangles by her knees from my arms.

Gina shakes her head helplessly. ‘I haven’t sat down all day, and then she wouldn’t take off her coat until I’d worked out the sleeps.’

‘Stop calling her “she”.’

‘Stop dodging the issue. Have you been with Alison?’

She looks at me at last, her eyes hard and angry, the peeler in her hand like a weapon.

‘Who’s Alison?’ says Matilda.

‘No one,’ we both say.

Still upside down, Matilda sings tunelessly.

‘No, I haven’t,’ I say.

A snort. ‘You expect me to believe that?’

Matilda’s the right way up again, smacking my stubble with her palms. ‘Naughty Daddy.’

‘Quit it, Matilda,’ says Gina. ‘Give me a goddamn break.’ She meets my eyes over Matilda’s head. ‘She’s ADHD, Mark.’

‘She’s not, nothing like it. Please stop saying that. She’s just a bit charged. There’s no space, we can’t swing a cat, so we fight, she rampages.’

‘Miaow!’ Matilda is loud in my face. ‘Can we have a cat, Daddy?’

‘Be quiet, for Pete’s sake.’ Gina furiously attacks another potato. When Matilda carries on miaowing, she closes her eyes. ‘Give. Me. A. Break.’

I beg Matilda to shush, and she does for a moment. Gina shoots me a look of despair. ‘Five minutes ago it was a bicycle.’

‘Can I have a bicycle, Daddy, please, please? It can live on the stairs.’

‘How many times, Matty, no!’ Gina yells. ‘There’s no room. We’ll fall over it. There’s nowhere to ride it. We don’t have the money, okay?’

‘We might have the money,’ I say.

She flings the potato in the sink and swivels to face me square on. ‘How dare you? Can’t you see what she’s doing?’

Matilda slithers down my body and runs into the living room. ‘I’m not HD,’ she shouts. ‘I could swing the cat in here. I would look after it properly and feed it, I promise.’

‘I mean it,’ I say quietly. ‘We might have the money.’

Gina’s mouth is pinched as if she’s holding pins in it. Quickly, speak. ‘Mum was killed this morning, crossing the road.’

She frowns, not sure if I’m joking.

‘I’ve been at the hospital, the undertaker, Mum’s house. That’s why I’m late.’

A tug comes at my elbow. ‘Granny Jonnson?’

God, what have I done? My child’s face is blank with dismay. I fall to my knees, seize her hand.

She’s staring at me. ‘Is Granny all right?’

I’m this little girl’s father. A grown up. I have to find the right words. ‘I’m so sorry, Matty,’ I say, ‘but the sad thing, the really sad thing that should never have happened is Mum was on her way to work, nearly there, crossing the road to her office, and she didn’t look properly, didn’t check—you know how you always should check? She stepped off the pavement, and... and a bus was coming... and the bus...’

Even for my child it seems I can’t soften the truth.

Gina bends over us, her hand on my shoulder. ‘The bus hit her, honey, and Granny died. Her body stopped working, and now she’s in heaven.’

Matilda’s green eyes are open as wide as they’ll go.

‘She didn’t feel any pain,’ I tell her. ‘She wasn’t hurt or frightened.’

That’s what the doctor said as he led me to identify the body. Knocked unconscious, he said.

‘Will her body work again?’

My throat clogs. I shake my head.

Gina squeezes my shoulder and says, ‘She’s very happy in heaven.’

Matilda withdraws her hand from mine, then brings it up in a fist as if she would hit me. She begins to wail. ‘I won’t see her. I wanted to go to her birthday, and now I won’t see her.’

‘It’s okay. It’s okay.’ Meaningless, but what else is there to say? And I’m trying to hug her, but she refuses to be hugged. Her wails mutate into howls.

Gina has her fleece off and wrapped round Matilda. ‘Don’t worry, hon,’ she says, rocking her. ‘Granny didn’t mind that you weren’t at her birthday.’

Gradually she quietens as Gina carries on talking and soothing. Gina’s Connecticut accent is softly convincing. It had me falling for her, way back at the start. It mesmerises the kids at the bookshop when she hops up on her stool and starts reading a story. But the thought nagging at my mind is how yesterday, in this same, relentless, soft accent, Gina backed Matilda’s preference for tea with a school friend over a ‘duty trip to her grandma’.

I stand up, observing the curve of Gina’s arm around Matilda, the corkscrew wisps that have come loose from the scrunchy, the knobs of her spine showing through the Vassar College sweatshirt.

‘There’s tons to do,’ I say, hearing the chill in my voice. ‘There’ll be an inquest, but they’re releasing the body. The hospital put me on to the undertaker, and he’s talked me through everything. I have to go to the registrar. Then there’s notifying people, sorting out a solicitor, planning the service. I’ll take tomorrow off work.’

She straightens to face me, holding Matilda close. ‘I’m so sorry, Mark.’

Our eyes lock. She looks scared. Part of me wants to shout, Like hell you are.

‘It’s not your fault,’ I say.

‘Why did you go there?’ she whispers later.

‘What?’

‘Why did you go to Nancy’s house?’

It’s dark in the bedroom. We lie side by side, naked but not touching. Matilda’s asleep in the other room.

‘I went to the undertaker first.’

‘But then to your mother’s.’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know. It was only ten minutes’ walk. The cat, I suppose. The neighbours have taken him.’

‘It seems weird to me. I think you’re in shock.’

I wish she would stop talking. She’s been asking about what happened—the call at work, the taxi to St Thomas’s, what the doctor said, what I saw—and I’ve been mumbling answers. So I’m lying here, looking at the patterns the orange streetlamp is making on the curtains, hearing a distant siren and remembering Mum on the mortuary table, when I feel Gina’s hand on my chest.

‘All this stuff...’ she says huskily.

I say nothing. She snuggles up under the duvet, the soft weight of her breasts on my arm.

‘I mean Alison.’ The name pains her. She pauses. ‘All of this fighting we’ve been doing.’

Her hand goes down to my limp cock, which she hasn’t touched in two weeks.

‘I mean, this is a wake-up call, isn’t it? A chance to see what’s important.’

She falls silent, stroking me, and I’m wondering what she thinks is important. Our fragile mortality? Mum’s money? My cock?

‘Matilda,’ she whispers. ‘You and me.’

I don’t want this, not now, it feels wrong, but she’s getting me going. She rubs her cheek on my shoulder, and I’m turning to face her, putting my arms round her. We cling for a moment, and then she’s clambering on top of me. Straddling me, tickling my face with her dark curls that smell of shampoo, and I’m feeling the kindness of it as she kisses me and guides me in.

I come quickly, and for a while we lie still. I want to be comforted; I want to feel close to her, but it isn’t happening. I’m thinking of the verbal abuse she’s been dishing out, which okay I’ve deserved, but this morning when she told me to leave it felt like an option, a kind of relief, and when she lifts her head and looks at me now I don’t know what I feel. My head’s in a mess; all I can think of is Mum.

I roll out from under, reaching for a tissue. Her hands follow me, stroking my back, and all at once it’s too much. I’m out of bed, escaping the room—‘Where are you going?’ she says—and I’m across the landing into the kitchen, where I slam open a cupboard, grab a glass, screw the cap off the Smart Price whisky and pour myself a slug.

Jesus, Mum, you were dancing, tipsily showing off to your mates on your birthday, and then, bam, knocked out. You were wearing green nail-polish; did the bus mess that up? What was under the mortuary sheet? Were you squelched by a wheel, your guts all over Whitehall?

Her face was okay, I tell myself. The bus didn’t smash up her face.

I’ve swallowed the whisky, and I’m back on the landing with horror jabbing in my brain. And I can’t stand to be with Gina, and I can’t risk showing this confusion to Matilda, asleep in the living room, and sure as shit Gina will come looking for me, and I’m damned if I’m going to hide in the bathroom. I feel huge. Caged. This pokey flat can’t contain me. I duck back into the bedroom, shutting my ears to her voice, grabbing my clothes, stuffing a few things into the rucksack. I get dressed on the landing.

She comes out of the bedroom, her mouth still moving, her eyes flashing anger. I shake my head. I take keys, wallet, coat, and I leave.

In less than an hour I’m back on Mum’s doorstep, turning the key and stumbling inside, anxious to find her whisky bottle.

But then, smooth and swift, there’s something in the house that calms me. Beneath the curry a more persistent smell of home. Behind the silence a sense of belonging and safety. She just popped out. She’ll be back soon.

I find the single malt in a cupboard, her best tumblers in another. I pour two generous measures, add water to both and carry them into the living room. I shift the ironing from the armchair, as she would do, and sit down. I lift a glass, clink it against the other and drink a silent toast to my mum.

Tueday

There’s a god-awful buzzing, a sick lurch in my skull. A digital clock face shows 5.59, and I clutch at it until the racket stops.

Memory kicks in. I’ve spent the night in Mum’s bed. I didn’t want to—smashed though I was, I couldn’t bear the idea of crawling between sheets that smelled of her—but the settee downstairs wasn’t long enough, and the sofa bed in the back-bedroom-turned-study refused to unfold—the desk got in the way—so I was left with no choice. On the floor is the heap of sheet and duvet cover I managed to strip from the bed before crashing.

I’m seeing her again in the mortuary. Her hair combed back from her forehead, showing the grey roots. Her eyelashes. Her eyes that don’t open. I throw myself belly down, smother my breath in the pillow and imagine her eyes opening, her face waking. Peek-a-boo.

For a while I can’t move, can’t allow time to go forward.

Matilda. I need my little girl. I roll off the bed onto my knees and fumble for the lamp. The light attacks me, I can barely see, but between blinks there she is, in the gilt frame by the clock radio, in her sundress with cherries, on the beach at Brighton, holding an ice lolly. On one side of her Gina leans in close, wearing a swimsuit, her curls loose and wild. On the other sits a man who last summer was me. His freckles are belligerent pink. His red hair sticks up from his scalp as though it’s seeking the sun.

‘Smile,’ says my dad.

I can feel the hard pebbles under my arse, taste the salt wind, hear the thunder of a breaker and its rattling drag back into the Channel. I’m looking at Dad, who crouches in the stones, peering at the image on the back of Gina’s camera.

Matilda looks ecstatic. Her face is alight. One hand grips the lolly stick; the other grabs at her daddy’s T-shirt. I try to imagine it, the feel of her small fist against my ribs.

The other photo in the frame was taken by Dad too. Me as a baby, being lifted from a bath by Mum’s hands.

He left before I was five.

Gina says I’m married, a father, I have to face my responsibilities.

I switch the light off again. It was hurting my eyes.

I’ve showered and drunk a load of orange juice. On my phone were three missed calls from Gina and a text: Where are u please call me. I’ve replied: At mums sorting funeral will get back to u. It’s the best I can do for now.

Another text reads: Hi mate. Pub with the lads this Fri? We’re forgetting what you look like. No need to answer; they’ll assume they’re my Alison alibi again. There’s a text from her too: Enjoying conference but don’t worry no one here half as dishy as you. There’s no need to answer her either.

I’m shaving in the half dark with the landing light on and the bathroom door open, finding the stubble with my fingers. I forgot to bring shaving kit, but there was a disposable razor on the side of the bath and the hand soap is lathering okay. This blade last scraped Mum’s armpit or leg, I’m thinking. This mirror last reflected her smile.

I have to get past a registrar and a solicitor. They must see everything from incoherent anguish through to brazen good riddance, but what will they make of me? I screwed up with the undertaker yesterday; he didn’t understand me at all, mistaking my distaste for him for glibness about death or my mother. Everything about him seemed false. The plastic flowers in his pokey office. His sombre face and dark suit. His ritual condolences. His tasteful, glossy catalogues. Younger than forty, pretending to be fifty. Off home later for his tea, not a second thought.

‘What will happen to her?’ I asked him. ‘Where will she be until the funeral?’

‘She’ll be looked after respectfully. Every care will be taken.’

‘But where?’

For a moment I thought he wasn’t going to answer, it seemed to pain him so much. He fingered a cufflink. ‘We have the use of excellent premises in Kingston.’

My jaw tenses now at the memory. I’m in danger of cutting myself. I lean back from the mirror, ambushed by the image of a wagonload of corpses bombing down the A3.

He wanted to know what kind of service. Offered to put me in touch with a minister.

‘She was an atheist,’ I told him. ‘She used to say, over her dead body did she want any mention of God over her dead body.’

I must have grinned, but he didn’t. ‘In that case, the humanists? Or you may prefer to conduct your own ceremony?’ He held out a booklet. ‘This offers an outline and a choice of suitable music and poems. Christina Rossetti is popular.’

Not Cyndi Lauper, then. I began glancing through the brochures. The coffins were hideous, the prices outrageous.

I chuck the razor in the basin and rub my face with a towel. Then as now I couldn’t shake off the image of Mum’s waxy-white skin, the way she looked dead not asleep, the skull beneath all too evident. ‘So,’ I said bleakly. ‘Cold storage in Kingston.’

He puckered as if I’d made a bad smell. ‘That’s not how we see it. Your mother’s remains will be treated with dignity at all times in a temperature-controlled environment.’

Bastard. Making me out to be flippant. Couldn’t he see I wanted the solace of straight talking. The reality of death, its ordinariness and inevitability. Isn’t it his job to give every mourner the story they need?

‘Would you prefer to peruse the options and give us a call?’

Preferring his pompous, preposterous jargon.

‘No, thanks. I’ll choose now.’

I picked the cheapest coffin, as Mum had more than once told me to do. Then spent a fortune on flowers. ‘White,’ I said. ‘Masses of white flowers.’

‘The florist will be informed of your wishes.’

I’ll have to go there again. He offered a choice of ‘robes’ for her to wear in her trashy coffin. I said she wouldn’t be seen dead in them; I would bring her own clothes in. I try not to think of his hands on her broken body.

I’m back in the bedroom, rooting through my rucksack in the dark for clean pants, noticing the smell of spilled whisky. It’s freezing in here; the radiator must be off. I pull on pants and socks, then T-shirt, sweater, jeans. Battling to get the second leg in, I collide with the heap of sheets and nearly fall over. And suddenly I’m furious angry—with the undertaker, with the tangle of bedding, with Mum. ‘How the hell could you do this to me?’

I grab the heap and her nightdress and head for the door. There’s a laundry bag hanging there. I swipe it from the hook, scoop her dropped towel from the landing, and I’m down in the kitchen in the faint light from the hall, on my knees, ramming the whole lot into the washing machine. I find powder next to me, chuck some in, slam the door shut, twist the dial and press go, lean my head against the cold metal. There’s a pause, then the dull thump and judder of released water, the first turn of the drum.

I groan as I get to my feet, from pain or grief I don’t know. I don’t know who to be, what to feel. I hold on to the machine, needing its pulse, its matter-of-fact energy and purpose. Minutes pass.

Coffee. I flip on the kettle, watch it boil, fill a mug. Then I sit awhile, nursing it, sipping it slowly, watching Mum’s last wash go round.

I’m thinking about my fifth birthday. It must be years since I replayed the memory, but it springs into life. I close my eyes and I’m back there, somewhere in south London, hiding behind the sofa in the flat that Dad has recently abandoned me and Mum for. I’m pulling at a hole in the brown-tweed upholstery. There must have been presents, and a cake, and perhaps I had some fun earlier, but in my memory I’m lying low between skirting board and sofa, my nose prickling with dust, pulling at the hole to make it bigger and watching my tears drop on the carpet. The other kids have gone home. Dad’s girlfriend was here pretending to like me, but she’s disappeared. There was music but it has stopped, and now they’re looking for me: my mum and my dad.

‘You’ve upset him,’ she says.

‘Don’t be daft, Nancy. He’s had a great time.’

‘I knew this was a mistake. He’ll be upset for days.’

‘He needs his dad, Nance.’

There’s a horrid pause as if they’re both shocked. Then, ‘Say that again,’ she dares him.

Silence. I strain my ears and then jump because Mum’s looking at me over the back of the sofa. ‘I’ve found him. He’s here.’ She smiles in the way I know is not a real smile. ‘Come along, Piglet. You and me have to go home.’

‘What did you call him?’

She doesn’t reply. She grabs hold of my wrist, hooks an arm round me and drags me up and over. I land in her lap and she hugs me. Her eyes glisten with tears. Her shoulder is bare. I want to sink my teeth into it.

‘What did you call Mark just then?’

She says nothing. She’s up on her feet, yanking me across the room, her fingers clamping my wrist.

‘He needs a dad, Nance.’

She swings round, shoving my face into her skirt. ‘If you say that once more, God help me I will kill you.’

Don’t say it. Please don’t say it again.

Dad says nothing. Mum says nothing. My nose is squashed against her belly, which smells of the car and the sunshine outside.

Then we’re moving, fast, out of the room, through the hall towards the open door, the bright street. I’m resisting, but she’s stronger than I am.

‘Come on, Piglet,’ she says.

She slams the door as we go, but too late. Dad’s voice follows us, mocking. ‘Oink, oink.’

Dawn is breaking outside. I cross the kitchen to roll up the blind but then drop it again double quick. Mum’s cat was on the sill looking in—I’ve barricaded his flap—but worse, the neighbour and her two kids were an arm’s reach away, leaning over the low fence between my kitchen door and their kitchen door, shaking a packet of cat biscuits. One of the children has started to wail. I must have scared him.

Shit, I don’t need this.

The key’s by the sink. I fling the door open. A freezing wind smacks my face, and the cat scurries in past my ankles.

‘Sorry. We didn’t know you were there,’ says the woman.

In the grey light she looks older than she did yesterday, mid-thirties perhaps. Her face is sleep-creased. She has the small boy in her arms, and she’s clutching her dressing gown to her throat.

‘No. Yes. I’m...’ Piss off and leave me alone.

The child howls. ‘Hush, Christopher, it’s okay.’

‘Where’s Nancy?’ the older child demands.

‘In Kingston,’ I say.

The woman translates. ‘She had an accident, Josie. That’s why we’re looking after Mog.’ She hesitates. ‘If you still want us to, Mark?’

‘Yes... er... Jean, if you don’t mind.’

‘It’s Jane. And don’t worry, we love Mog, don’t we, kids?’

The cat’s sniffing his empty bowls in the kitchen. I march him back and dangle him over the fence. The little girl clamps him to her chest, glaring at me.

‘I’m sorry,’ I manage, ‘if I seem... It’s been a shock, and—’

The washing machine crescendos to a deafening spin, spewing suds into the drain by my feet.

‘A dreadful shock,’ shouts the woman. ‘I mean Nance. She was great. It’s not fair.’

‘I may be staying,’ I shout back, ‘but the cat...’

‘It’s okay, Mark. I’m fine with the cat. Come on, Josie.’

She turns and goes into her house.

For a while I drift, making toast, drinking more coffee, wishing I hadn’t given up smoking, and thinking how we’re all heading for Kingston, until finally I pull myself together enough to look for the will, which I’ll need to give the solicitor.

It takes no time to find it. For all her dancing in kitchens, Mum spent thirty years in the government legal service, so she knew how to file. In the back-bedroom-turned-study, in a box labelled ‘personal and finance’, in a folder tagged ‘key documents’, there it is, tucked in with her passport and certificates of birth, marriage and divorce.

She’s left everything to ‘my son, Mark Daniel Jonnson’.

It’s still too early to arrive at the registrar, so I fetch a refill of coffee and hack into her laptop. Password Matilda, what else? Her emails include an online utility bill, five happy birthdays, what looks like a spate of round robins from her library book-group, two offers of penis enlargement and a savings-account update. I leave them unopened and scroll through her contacts.

Here they all are: her best mate from Kent, various Muswell Hill neighbours she’s kept in touch with, her school and university friends, office colleagues, many names I don’t know. Everyone who cares must be listed here. I log into my own account and start composing a message. I am sorry to tell you that on Monday 24 November my mother, Nancy Jonnson, was knocked down by a bus...

Thank heavens her parents are dead. It would have been tough breaking this to them, not knowing what emotions to offer or expect. I hardly knew them. She never spoke much about her childhood, shook her head if I asked. ‘No love lost,’ she would say. ‘I don’t know why they bothered to have me.’ On the infrequent occasions I went with her to Kent, her mother, falsely bright, radiated anxiety that I might make a mess, move a cushion or something, while her tall, craggy father, silent and self-absorbed, barely concealed his impatience for us to be gone. When they were dying, fairly briskly one after the other, Mum never suggested I visit them in hospital; I made do with looking solemn at their funerals.

Oh Jesus, I’ll have to invite people here for some kind of wake. I stand up, fuming and mutinous, knocking the ceiling lamp with my head, dislodging dust. I don’t want to do this, Mum, even if I knew how. I don’t want to make sandwiches for your mates and hear their condolences.

I drop back on the chair and start jabbing the keyboard, deleting the spam and the library stuff. I try to calm myself by opening the birthday greetings, picking over each message for fragments of her. I find only clichés—Hi Nance... sorry it’s late... hope you had a great day—but one catches my eye.

Happy Birthday with Love to my Beautiful Sexy Nancy. How is my Darling? Me I’m still driving the bus, whinging that it would make more sense to do something else, but you’ve heard that B4 and I stay in my Groove. Relationship-wise, well on we go. Things seem good at the moment but last month we nearly seperated. It would be Nice if just ONCE she could conceed a point if you know what I mean. You’ve heard this B4 too but I still hope to get back to see You who I don’t say lightly is still steaped with love in my soul. Now I’ve looked at a certain Photograph of you I have some energy to get behind the wheel. Lots and Lots of Love, Oz XXX P.S. I will send a proper card soon.

Nerdy but tantalising, and I’m breathing more easily, sensing how Mum would have smiled at the spelling mistakes. I can see her tapping out a reply, tongue between teeth, and the thought makes me smile too, although I have to say the liaison surprises me. She had romances now and then, the odd fling, but with professional types, as you’d expect. It seems feelings went deep here, on his side at least, and Mum never got in deep. Each bloke I heard about was soon history.

There was a guy who moved into the Muswell Hill flat with us a couple of years after Dad left. His name wasn’t Oz. I can’t remember what it was. He was decent enough but it didn’t take either with Mum or with me, and he eventually pushed off.

In recent years she’s seemed immune to the need for male company, cheerfully self-reliant. ‘Friends are more important than lovers,’ she once told me. ‘I’ve nothing against men, but they either bore me or I get in a muddle with them. Not their fault—it’s the way I’m programmed. I’m best off steering clear.’

This Oz guy is married. Did she get in a muddle with him? He doesn’t sound like someone she would even go on a date with.

The other emails can wait, but he needs answering. I click reply, paste my draft in and play with it. Given his job, I decide not to mention the bus.

Oz, I am sorry to have to tell you my mother Nancy was knocked down yesterday, crossing Whitehall on her way to work. She died instantly, felt no pain. The funeral will be at Putney Vale Crematorium, 2pm Wednesday 3 December, white flowers, and you’re very welcome to come. Mark Jonnson

I click ‘send’. Off it goes. From her email address not mine, which seems okay for this one. He’s hotmail, so who knows where in the world he’s stuck in his Groove. Will he be broken-hearted, I wonder, or was he just dishing out randy patter?

Time to go. I log off. Beyond the window there’s a pale blue sky chased by wispy clouds and blurred by the tears in my eyes.

Going to fetch my wallet, I stall in the bedroom doorway, shocked to see the mess I’ve made exposed by the daylight: my things scattered across the floor, the spilt whisky smell on the unheated air.

Grief smashes into me. I can’t see Mum in this room any more. I’m losing her too fast.

I cross to the bedside and pull open the drawer, looking for her. Among the jumble of pill bottles and half-used tubes of cream, there’s a small vibrator, the colour of candy-floss.

I pick it up, turn it on. It buzzes gently then subsides, its battery flat.

My legs give way. I sit on the bed, grinning and crying.

June 1978

Oh God. Harry. What the hell had she done?

Her mouth was parched from smoking his Gauloises. Her sweat smelled sour. Her head thumped and stabbed. Nancy swayed upright into blinding sun. She’d been flying too high when she got home last night to bother closing the curtains.

There were record sleeves all over the floor. She vaguely remembered yelling along with John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John before Laura in the bedsit next door had banged on the wall.

She began stumbling around, gulping water, washing her face, scrubbing at her armpits, pulling on a blouse and yesterday’s crumpled black skirt. She leant into the mirror, avoiding her eyes, trying to make sense of her hair, trying not to remember, trying not to feel shame. Because, bloody hell, Harry. His hands up this skirt, tugging down her tights, squeezing her bum, finding her wetness, while she wriggled her fingers through his pin-striped fly to give him the best hand-job his Y-fronts allowed.

No amount of shame could undo it. She was super-intelligent, for heaven’s sake. She’d outshone her peers to get a foot on the ladder of one of the most prestigious legal careers going: drafting the laws of the land. She should have the sense to at least pretend to be decent and dignified. But last night she’d downed five halves of Guinness with her married boss in a pub near Baker Street Underground station, then jerked him off in a shop doorway before letting him hail a cab for her to come home alone in. Her back still hurt where it had been jolted against the door handle.

And now she had to go into work and face him, had to be all day in the same room as him. She wanted to ring in sick, but that would be cowardly. She must set off at once before she lost her nerve; keep moving—the Underground, the Trafalgar Square crowds. She wouldn’t falter. She would march up to the demure, eighteenth-century frontage of 36 Whitehall and in through the smart entranceway. She would nod to the security guard and keep going, keep going, into the big, square office where Nerys would be chewing her nails checking the typing, and Edward’s face would brighten, and he would get to his feet and say, ‘Good morning, Nancy.’ And there by the window would be Harry. Oh God.

He would make some clever-dick comment about her torrid love-life keeping her in bed of a morning. He would loll back on his chair and arch an eyebrow as if to say he could lift his big wooden desk with his erection. And she would smile and say, ‘Sorry, I’m late,’ and slink to her place by the door.

And Edward would come and stand in front of her desk, blocking her view. He would say, ‘Actually, you do look a bit under the weather. May I fetch you a coffee?’

2008, Friday

It’s two-thirty and I’m unlocking the door to Room 306.

‘I’ll get the blinds up,’ says Keith.

I’m functioning better: still holed up in Battersea at night but back at work in the daytime, doing my damnedest to avoid more condolences. I’m safe from them in class; it doesn’t occur to my students to ask after my wellbeing.

It’s stuffy in here as well as dark. The altruistic part of me I call Teacher Guy spreads his papers on the front table and pastes a smile on his face. ‘Thanks for arriving on time.’

They nod, hungry for praise. Teacher Guy cares passionately about his job, would dearly love to get them reading, wants to give each of them personal attention, but he’s stymied by their mixed abilities and the rigid curriculum. Today he’ll whiz them, uncomprehending, through the differences between formal and informal letters before heading back to the phonemes that may conceivably yet change their lives.

This year’s English 1 students are the usual miscellaneous misfits: unschooled immigrants who lack the literacy for an ESOL class, plus a few home-grown inadequates. The same few as ever are punctual. Keith, built like a professional wrestler, tugs at a window cord, eases a blind past its sticking point. He’s a retired labourer who knows everything under the sun except how to link sounds to letters. He could learn this too if he let himself forget his embarrassment, stopped joking and covering up.

Wayne knows his way to the bus stop. His face is pockmarked and his eyes don’t quite focus. He’s forever slipping out of class for five minutes, returning with alcohol on his breath. Teacher Guy stopped coaching him on spelling the months of the year when he realised Wayne had no use for them, guessing when prompted that there might be thirty-six and unable to say which one contained Christmas. But Wayne makes small breakthroughs. This term he’s learned that I-N-G spells ‘ing’, and he announces this happily whenever he sees it, which gives Teacher Guy a buzz.

The other two eager beavers are grandmothers, Congolese Patricia and Pakistani Nazish, who’ve devoted their lives to parents, husbands and children and now itch to live for themselves.

My mother is dead. The thought comes at intervals.

Today began with another hangover. Tuesday, Wednesday, most of Thursday, I stayed sober. A mountain of tasks kept me from brooding. But after I’d notified Mum’s friends and fielded their telephone calls, more or less planned the service, looked through her finances and delivered her files to the solicitor, decided beer and crisps will have to do for the wake and weathered two days of condolences back at work—I was overdue last night to hit the bottle. I tried to lose myself in my library book first—Germinal—poverty and wretchedness in nineteenth-century France—but the words danced on the page. This probably isn’t the best time to be reading my way through the complete works of Zola with Hemingway as light relief.

Waking in Mum’s house feels less spooky now. The bed has clean sheets, the radiator’s on and at seven The Today Programme starts murmuring the latest batch of gloom about the collapsing economy. My head was thumping this morning, and I was tempted to ring in sick, but an inner voice nagged me upright, gave me a shower and a shave, insisted I ate egg, toast and orange juice and marched me through the drizzle to the bus stop. There was no call to short-change my students.

Oddly, the inner voice sounded female. Not Gina. Too jolly and down to earth. Maybe Mum?

I close my eyes, grit my teeth hard, hold grief at bay. I think of Matilda doggy-paddling in my arms.

One bit of luck: Alison is still at the management conference. Since the shit hit the fan with Gina ten days ago, Alison’s been angling for me to move in with her, and I can’t face that pressure today. It’s tricky that she’s my boss; I wasn’t thinking too cleverly when I succumbed to her charms. I don’t usually find blondes attractive, and Alison’s interests don’t extend much beyond clothes, middlebrow fiction and television reality shows, but she’s quick-witted, funny, energetic in bed. Our affair was never going to be serious. I assumed she’d understood that, but it seems that she hadn’t. I’m in no hurry to tell her I’m spending my nights solo in a double bed this side of the river.