10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

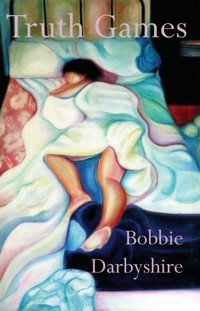

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

After the hippies and before the yuppies, between the advent of the Pill and the onset of AIDS, between the 'summer of love' and the 'winter of discontent', the newest game in town was sex. In mid-seventies London a group of friends play a dangerous game of open marriages, secrets and lies. "It's only sex, Ann. It won't hurt us," claims Lois, beautiful, talented and determined to get whatever or whoever she wants without being held back by her longsuffering husband, Hugh. Wherever they are, sex is there for the taking. But can love be free? Truth Games bares all. It's fast, funny and sexy, but as the summer heat increases, stakes are raised and consequences have to be faced…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

By the same author

Dedication

Epigraph

Half Title

Preamble

JUNE

New Rules

Playing Gooseberry

Advertising

House of Cards

Playing House

False Move

Friendly Game

JULY

Away Game

One More Player

Home Runs

Ducks and Drakes

Girl Talk

AUGUST

Snake and Ladder

Party Game

Paris

Home Truth

SEPTEMBER

Truth Will Out

The Meaning of Words

OCTOBER

Detective Stories

Straight Talking

Spectator Sports

NOVEMBER

Playing Away

Playing Dirty

DECEMBER

Playgroup

Confession

Hidden Truth

JANUARY 1976

Guessing Game

Solitaire

In Vino Veritas

Double-think

FEBRUARY

Beginners

Ethics

Merely Players

MARCH

Diplomacy

Joining the Dots

Contracts

APRIL

Child’s Play

Playing to Win

Revelations

MAY

Tongue-tied

Chinese Whispers

Other Engagements

The Mating Game

A Bad Call

Endgame

JUNE

Truth Games

Bobbie Darbyshire

Published by Cinnamon Press,

Lytchett House, 13 Freeland Park, Wareham Road, Poole, Dorset, BH16 6FA

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Bobbie Darbyshire to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. © Bobbie Darbyshire 2009. This edition © Bobbie Darbyshire 2010.

Print Edition ISBN 978-1-905614-72-1

Ebook Edition ISBN 978-1-78864-186-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press. Original artwork ‘dreamstime’ by ‘loveliestdreams’/dreamstime.com.

Le Cheval Rouge by Jacques Prévert translation copyright c 1958 by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Reprinted by kind permission of City Lights Books.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress.

Acknowledgements

I owe a debt to many kind people who commented on the draft. My thanks go to:

Jan Fortune-Wood and Stella at Cinnamon Press; Jüri Gabriel; Joan Deitch at Pollinger; my mother Beryl and sister Pip; Bob, Colin, David, Faye, Joan, Julie, Keith, Marek, Nick, Nina, Peter and Sarah at West Hampstead Writers; Brad, David, Kevin, Richard, Rupert, Vicky and Wendy at Original Writers; Adam, Angela, Berend, Carla, Joe, Julie, Kathryn, Neil, Paul and Peter at Writers Together; Andy, Bruce, David, Nicola, Richard, Robert, Sophie and Tamsin at National Academy of Writing; Alison Gray, Barry Weatherstone, Bernadette Mongellaz, Dave Quinton, Debbie Collier, Elizabeth Barton, Graham Perry, Ian Jewesbury, Janet Mitchell, Jonathan Masters, Liz Adams, Luc Richez, Maurice Paley, Peter Huitson, Richard Colombo, Roger Hurrey; Bill, whom I never met, who saw the manuscript and left a letter for me in St Ives; and most of all to Jan Fortune-Wood at Cinnamon Press for saying yes.

By the same author

OZ

Love, Revenge & Buttered Scones

The Posthumous Adventures of Harry Whitaker

The Third Bus

In memory of Richard Colombo

In merry-go-rounds of lies

The red horse of your smile

Goes round

And I stand rooted there

With the sad whip of reality

And I have nothing to say

Your smile is as true

As my home truths.

Jacques Prévert (translated by Lawrence Ferlinghetti)

Truth Games

After the hippies and before the yuppies, between the advent of The Pill and the onset of AIDS, between the ‘summer of love’ and the ‘winter of discontent’, the newest game in town was sex.

JUNE

New Rules

Lois sighed, and Hugh drew back hurt into his own warm space in the bed. He would have to say something soon.

He made himself speak, as though it were nothing. ‘You don’t fancy me much lately, petal.’

‘Ineverreallydid.’Sherolledawayandlaystill.

It had him catching his breath. Insults were standard, she never pulled her punches, but calling her ‘petal’ was cue forher to counter by calling him ‘prawn’, a reference to his sun- shy skin and red hair. ‘I never really did, prawn’ was what she ought to have said.

He stared at her tangle ofdark curls. He was being foolish; she was probably hung over. Saturday night with the Goldings was getting to be a habit, and too often they paid for it on Sunday morning. His own head was clear. At forty, he was feeling the need to go slow with the wine, to put a hand over his glass when Jack lurched by on his life mission to top everyone up.

He snuggled close again, kissed Lois’s freckled shoulder, breathed in the lazy, sleepy smell of her. ‘Poor petal. Shall I bring you a cuppa?’

She half-turned her head. ‘Not even at the start, I didn’t. Not properly.’ She sounded despairing. ‘It wasn’t really physical. You know?’

It was happening, what he’d dreaded so long. He tried to see her eyes.

‘Butwehadsomethingbackthen,’hesaid,‘Westill do.’

‘If you say so.’ She shook her head, chewed her lip. ‘Although sometimes I wonder—was I just showing off?’

She was sliding from his arms, launching herself into the day. She had swung her legs clear ofthe bed and was reaching toopenthecurtain.Thestreamofsunshinedazzledhim, bouncing offher naked flesh and revealing the hot dust in the air around her.

Horatio struggled from his basket, wagging and snorting and sneezing. When Hugh leant to fondle his ears, the dog promptly heaved himself onto the bed and covered his face with slobber. ‘Ugh! No! Get down, you beast! Now I understand how my poor wife feels.’

He looked up, hoping for a smile, but she showed no sign of having heard. She was contemplating her reflection in the longmirroronthewardrobedoor,nolightinhereyes.Andhe knew he’d lost her. Ten years, his time up and she’d be gone. He couldn’t bear it. No choice, no more time to consider; he must make his offer at once. Hugging the dog to his chest, he took a steadying breath and made himselfspeak the words.

‘Iwouldn’tmind.’Theysnaggedinhisthroat.‘Youknow,if you wanted adventures.’

Sheturnedfromthemirror. ‘Seriously, Lois.’

Asecondwent by.

‘IfIfucksomeoneelse,youmean?’

He closed his eyes. ‘Truly, I would the gods had made thee poetical.’

‘Youwon’tgoallhurtandholier-than-thou?’ Won’t, not wouldn’t.

‘No,’hisvoicehoarse,‘Iwon’t.’

He was offthe bed, taking a step towards her, wanting to rewind the ten years and see the starry-eyed student who’d seduced him. ‘My love, I tried to teach you ethics once and failed. I’ve learned my lesson.’

Shepulledafaceandturnedbacktothemirror.‘Thereyou go. Pompous already.’

My god, she was right. In that case, ‘Lois, listen.’ He took another step. ‘I mean it. I promise. No moralising.’

Her dark-blue eyes observed him from the depths of the mirror. He gathered himselfto speak plainly.

‘I will not, repeat not, go all hurt and holier-than-thou if yousleepwithanotherman.Withadozenothermen.Iknow

I’mnotallyouneed.Iloveyou.You’refree.Useyourfreedom. I’ll still love you.’

Hepaused,thenadded,‘Trynottoleaveme.’ ‘Do you mean this?’

Atlastshewassmiling. ‘Yes, I do.’

LikeachildonChristmasmorning. ‘You honestly won’t mind?’

‘Crossmy heart.’

He cupped her face in his hands. She had her arms round him now. ‘Thank you, prawn.’

He swallowed. The transaction was oddly exciting. Come back to bed, he wanted to say, but she was pulling on jeans.

‘Yes... time for breakfast.’ He backed away, groping for his dressing-gown and the door handle and nearly tripping over Horatio, who lumbered ahead. As he reached the bathroom,he found he was trembling and sweating. He’d promised too much.Andwhatcoulditbuyhimbuttime?Shewoulddespise him; she would still leave him. But even if the gamble was futile, what other way was there? Love wasn’t a chain.

He stared into the mirror, forcing his hands to manage toothbrush and paste. Why did she marry him? He examined his nondescript, middle-aged features. He’d never understand it. Why did she detach herself from the crowd of wide-eyed eighteen-year-olds and waylay her tutor? And how had he persuaded himself it wasn’t lunacy to let himself love her, this impulsive, unsuitable student who put his heartbeat on hold, standing too close, with her eyes on his lips? Who told himshewasn’tthelovey-doveytype,butreallylikedhim.Likedthe way he explained this ethics nonsense—when did he get pompous?—and knew the best bits from the boring books.

‘Shakespeare’snotboring.’

‘Ifyousayso.Goonthen,tellmeanother.’

‘It were all one that I should love a bright particular starand think to wed it, she is so above me.’ That was her favourite.

Itwasimpossible,hetoldher.‘I’myourphilosophytutor...yourmoraltutor.’

She was shameless. ‘Okay,’ she said, ‘let’s get wed, have a party, go public. Sort out all that rubbish.’

‘Marriage?’ He’d fought vainly to hang on to reality. ‘You’d regret it in no time. I’d make you unhappy. Then you’d make me unhappy.’

‘So what?’

And suddenly that had been his thought as well. So what? His life was too sheltered. The world was full ofyoung people takingnocarefortomorrow.Hewasn’tyetold.Whyshouldn’t he join in?

‘Don’t worry,’ she’d murmured in his ear as he finally succumbed. ‘It doesn’t have to be forever.’

There it was, from the start. Joy and uncertainty, it was always the deal: in Fulham 1975 as in Brighton 1965. The stakeswerehigher,buthestillwantedin,whichmeantkeeping thisimpossiblepromise.Hemustn’thideamomentlonger.He must show there was nothing amiss.

He left the bathroom; checked the bedroom, empty; then found them both, Lois and Horatio, guzzling their breakfasts in the kitchen. She was piling Old English marmalade onto a slice ofburnt toast.

‘So what shall we do today, prawn? Give Jack and Tessa a ring? Tell them, stuff your headaches. See if they fancy that Cuckoo’s Nest film?’

Her exuberance lifted him. When she was happy, how could he be sad?

‘Goodidea,petal.AndAnn, too.’

He spooned coffee into a mug, poured muesli into a bowl. The nausea was gone. His hand was steady. Yes, he was equal to this. He would keep his word and perhaps, in spite of everything, he wouldn’t lose her.

Hewouldtryveryhardnottobe pompous.

PlayingGooseberry

‘God, Lois, I miss you,’ Ann laughed, ‘I thought work could never stop being heaven, but it isn’t the same with you gone.’

It was Thursday, and the two of them were sharing a scratch supper in Fulham while Hugh attended some end-of- term do at the university. The day had been another scorcher, and the air in Lois’s big, jumbled kitchen was gluey with heat. Lois was throwing red wine down her throat, one bottle already half-empty when Ann arrived. Lois looked radiant, more teenage than twenty-eight in a shocking-pink T-shirt and hipster flares, while Ann felt a wreck in her sweaty work clothes.

Lois came round the table and squashed Ann in her arms. ‘How can you be missing me? This makes three times you’ve seen me this week. And we’ll all ofus be in Italy soon.’

‘All of us. Exactly. I never have you to myself any more. I don’t want to whinge, but it’s always the Fairchilds and the Goldings these days.’

‘Ohhelp,’Loissaid.‘Havewegoneallmarried-coupley?’

‘Yes, you have.’

‘It’sTessa’sfault,’Loisprotested.‘She’stheonewhoissued gold-embossed invites and keeps saying “my husband”. Anyway,’ she paused to swallow more wine, ‘no way am I coming back to work, because, darling,’ she drawled, ‘I’m a photographer now.’

‘Andakeptwoman,’saidAnn.

‘But,ofcourse.Cheers,Hugh.’Loistoastedtheceiling.

She was half-pissed. Ann wished that she could be too, but the drink was going nowhere.

‘So. Did you develop the picture from Tuesday yet? The one you took ofTessa?’

Loisnodded.‘Itwasn’tofTessexactly.Wait,I’llshowyou.’ She ran to fetch it, past Horatio, who’d padded in looking for Hugh.

‘Hi,doggo,’Annsaid.Hewaggedhistail,butthenpadded out again, back to his favourite leather armchair in the living- room.

Ann moaned softly. Rod Stewart’s abrasively seductive voice wasn’t helping her mood. Lois had played nothing elseall evening. ‘Rod’s edible,’ she’d announced as she flung open the front door and lifted Ann half off her feet. ‘I always put him on when I’m randy.’ Which had Ann feeling randy herself and acutely frustrated. Was it really two years since Ed left?

Here came Lois with the photo. ‘It’s good, don’t you think, Ann? Tell me it’s good.’

The picture wasn’t of Tessa, although she was in it, frowningintheforeground,hunchedoverherravioli.Stripped ofthe clatter ofcutlery and the smell ofsmoke, wine and pasta, the wide-angle view showed a sea of mouthing faces. Across the crowded trattoria, so many people were animated, arguing or gesturing, furious or exultant. Had the hot weather made them excitable?

‘Gosh,Lois,it’sfabulous.’

‘Forget “fabulous”. Do you think it’s professional? Do you think I could sell it?’

‘I’msureso.’

‘No,beserious.HughthinksIwill.’

‘This photo?’

‘Lotsofthem.Hereallybelievesinme.He...’ Ann looked at her. ‘What?’

Loisgrinned,shookherhead,tookaswigofwine. ‘What?’

‘Youwon’ttell?’

Annshookherhead.Shenevertoldanyoneanything.

‘It’s amazing,’ said Lois. ‘Whatever I want, he finds it out and says go ahead, do it. First photography and now... wait for it,’ she paused naughtily, ‘sex. Other men.’

Annsat back.

‘But, Ann, he could see I was dying ofboredom. He says I’m free. He won’t mind. And he means it.’

She leant forward again anxiously, her eyes on Ann’s face. AnntorethecellophaneoffanewpackofBensons,litone andstarted toflattenthegoldpaperwitha finger.

Lois was crouched at her feet now. ‘He promises he won’t. And with Hugh a promise is like putting his soul on the line.’

Annshookher head.

‘It’sonlysex,Ann.Itwon’thurtus.’

Onlysex?Shetriedtoimagineit.MaybeLoiswasright,but how must Hugh be feeling?

‘Won’tit?’

‘Quitetheopposite,’Loissaideagerly.‘Ireally wasfedup— I was getting niggly with him for no reason. Whereas now I keep looking at him and thinking how lucky I am.’

When Ann snorted, ‘Yes, you jammy sod, you are,’ Lois let out a whoop, leapt up from the floor and hugged her again. Ann nuzzled into the hug, trying to feel better. ‘Okay, my lover, you’re persuading me.’ She used the West-Country endearment for all of her friends, but for Lois it wasn’t too strong. She couldn’t always agree with her, but she loved her nonetheless. Hugh too. Like family. Better than her annoying brothers and sisters.

She leant out ofthe hug to take a drag on the ciggie. ‘Sodid you come clean about the rugger-bugger?’

Lois fell back on a chair. ‘Oh... shit... maybe I should. Do you think?’

‘Have him round to tea and a discussion of ethics with Hugh?’

Thatwassnide.

Loiscontemplatedherwine.‘Problemis,’shesaidatlast,‘it would be like rubbing Hugh’s nose in it.’

Ann sucked hard on the ciggie, wishing she didn’t feel so horribly priggish.

‘Look, whatever he asks me I’ll tell him, okay? And whatever he doesn’t I won’t. Then, no lies, it’ll be up to him.’

Therewasnopointinarguing.Loiswasirrepressible.

‘But thank you, because now I’ve decided, clean slate. I’m going to kick Rug-bug into touch. Or is that football?’

‘Lois,Ididn’tmean—’

‘It’sfine,’shewasinsisting.‘I’mseeinghimtomorrownight

whileyoulotplaybridge.I’lltellhimthanksandgoodbye.’

She raised her glass, ‘Bye bye, Rug-bug,’ and drained it. ‘Plus I’ll be discretion incarnate, nobody knowing. You’ll be my only exception.’ She reached for the bottle. ‘Isn’t Hugh wonderful?’

Annnodded.‘He’salovelyman.’

Lois was up, dancing around the kitchen to Rod Stewart. Ann watched her and smoked and thought ofpoor Hugh.Not much to look at: she could understand why Lois, having all, kept wanting more; but special nonetheless. A bit like Fred Astaire, she often thought, with his sandy, straight hair and his wide-mouthedgrin,andthattouchoftheold-fashionedabout him, as though he might spin you off on his arm into the moonlight. So kind, so gentle and clever, and so much in love with Lois.

Loispausedtorefillherglass.‘ToHugh!’

‘ToHugh,’echoedAnn.Shestubbedthecigarette.

‘Who is so brilliant,’ Lois said earnestly. ‘Cos what apalaver, when you come to think about it. What incredible nonsense this monogamy stuff is.’ She waved the glass, splashing wine on the floor. ‘Take Jack and Tess. Good for each other, happy together in their argumentative way. So it shouldn’t make a blind bit ofdifference that he’s fucking that silly cow.’

‘Lois!’Annstruggledtokeep her facestraight. ‘Pamela’smyfriend.’

‘Come off it. As I was saying, no difference at all. But Tess’d blow a gasket ifshe knew.’

She was off again, swaying dreamily in the space between fridge,cookerandsink,observedbyHoratio,whostoodinthe doorway wagging his tail. Ann lit another cigarette andwatched the glowing tip start to eat its way down. Tomorrow night the Drunken Bridge Club would meet in her flat, as itdid every alternate Friday: Jack and Pamela, herselfand Hugh, while Tessa worked overtime and Rug-bug scored his last try. She rolled the scrap ofgold paper, then unrolled it again.

JackandPamelahadbeenatherplacethisafternoon.She hadn’t been home yet; she had that to face. Soon, she would have to leave Lois’s hugs and this warm, untidy kitchen and take the tube to Camden Town, where there’d be no option buttodragherfeetalongtheHighStreetandthroughintoher road, to kick the day’s crop of chip papers into the gutter, tiptoe down the area steps to the shadowed front door and reluctantly turn the key. And there she would be again, prowlinglikeaninterloperinherownhome,catchingthedrift of Jack’s classy cigarettes in the hallway, fingering the glasses gleaming on the draining board, staring at the neatly remade bed with its tight hospital corners.

Pamela, the staff nurse: how Ann detested her pedantic tidiness. And how had it come to this? It was high time she saw action herself.

The music had stopped and Lois was enveloping her in another hug. She looked anxious all ofa sudden. ‘We mustn’t tell Tess about me and Hugh.’

She hiccupped.

‘Iwon’ttellasoul.’

She hadn’t even told Lois about Jack and Pamela; it was Hugh who’d done that.

Lois hiccupped again. ‘It’s tempting. I keep wanting to say, “Hey Tess, why don’t you give meaningless sex a whirl, same as your Jack does.”’ She took another swig ofwine. ‘How are Jack and Pam, by the way? Has he managed to ditch her yet?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Hughsays,can’tbelong.’

Annnodded.‘He’sright.YoucanseeJack’spissedoff.He’ll soon be telling her in words ofone syllable.’

She watched gratification, jolted by hiccups, spread across Lois’s face. The penny dropped, and her stomach. ‘Oh Lois, you don’t? You and Jack? Oh my God, Lois!’

Lois grinned, hand to mouth. ‘I fancy him something chronic. Oh help, aren’t I awful?’

‘Yes,youare!’

‘It’s only sex, Ann, I promise. He’s safer with me than with Pamela.AndTessawon’tknow.’Shegrinned,showingherlittle

white teeth. ‘New bottle. New toast. Turn Rod over.’ She stumbled out ofthe kitchen.

Ann sprang from her chair, almost ran after her. She wantedtosmackher,toshakeherandtellhertowakeup.Lois and Jack? Too much, God, how horrible! How could she even thinkofit?Hughpretendingnottomind;Tessaunabletosee. As ifthat made it okay. God!

But already the shock was subsiding. It began to seem possible. More than that, unavoidable. A done deed, the stain already spreading.

Whynotme?Thethoughtspranglikerageinherhead. AndwhynotpoorHugh?

Horatio, sensing excitement, was snorting and nudging her hand with his nose. The image of Hugh’s face was floating before her. Fred Astaire’s smile. She closed her eyes and droppedbackonherchair.Asighspreadthroughher,starting in her shoulders and settling through her limbs. Her muscles relaxing. Hugh, ofcourse, Hugh.

Lois was back with the new bottle, filling their glasses. ‘So here’s the toast. To Italy.’

Ann patted Horatio’s head under the table. ‘To Italy,’ she agreed, shouting above Rod Stewart. ‘Let’s face the music and dance.’

Advertising

The next day, when Ann lunched with Tessa in a pub on the Strand,TessalaunchedimmediatelyintoarantaboutAlan,her boss. Ann could barely concentrate; her head was too full of secrets.

‘You wouldn’t believe what a sadist he is, Ann. He knows just how to wind me up.’

Ann nodded and murmured sympathy. Tessa was looking olderthanheryears,shewasthinking.Broadshoulders,square jaw:there’dalwaysbeensomethingatouchmasculine,but lately she seemed deliberately androgynous with her tailored suits and close-cropped hair.

‘He’sapig,mylover.Butyoucan’twin,soignorehim. Don’trisetoit.’

Mightaswelltellhertostandonherhead.

‘It’s him that won’t stop. He picks his times, waits until there’s someone else there so I can’t defend myself. This morning he gatecrashed my budget review meeting, and...’

Ann’s attention drifted. She shaded her eyes against the glare of sun from the high leaded windows and scanned the bar.ItwaslikeLois’sphotographagain:everyoneshoutingand animated, packed tightly around the oak-barrel tables, or standing, crushed together, in the spaces between. Three feet from Ann’s eyes, a man’s hand slid confidently over the curve of a woman’s buttock. Ann shifted on her seat, pushed her food aside, lit a cigarette and took a gulp ofwine. She needed to calm down. She sat back, willing the alcohol into hersystem, adding her exhalation to the smoke, hearing the tetchy stop-go of the traffic beyond the window. She tuned in to Tessa again.

‘When I’m alone with him, you’d think butter wouldn’t melt, he’s so smarmy. “My dear young lady, what a marvellous job you’re doing” blah, blah.’

Ann tried smiling, but Tessa didn’t smile back. The frown that Lois had caught with her camera was getting to be semi- permanent. She’d been just as belligerent three years ago when she marched into ATP, the little market research company whereAnn still worked.Tessa had been a whizz kid at twenty- four: nipping uneconomic projects in the bud, scrutinising the contracts, terrifying the partners but impressing the clients. Then,thisyear,she’dbeenheadhuntedbyRexAdvertisingfor the top job in their administrative department, where her unwritten main duty was to keep the vile MD off everyone’s backs.

‘... and I know, if I tackle him, he’ll deny all knowledge, make me look paranoid.’

AnnthoughtofLois.‘Sowhydon’tyouquit?’

‘Quit?’Tessa’snostrilswereflaring.

‘Jack makes enough money. Think what you really want to do, and go for it, Tess. Like Lois is doing.’

‘Thankyou,butI’mnoone’sdependent.’ ‘Don’t bite my head off.’

‘You think Lois is a model? She seduces her tutor, flunks out ofa degree, spends ten years sponging offhim—’

Anncouldn’tbearthis.‘LoislovesHugh.’ Did she though? Was Tessa right?

‘Italy.’ She changed the subject. ‘Two weeks with your husband in Italy and you’ll forget your horrid boss.’

Tessa’s scowl deepened. ‘I’m right off the word“husband.”’

Ann nearly choked on a lungful of smoke. For an awful moment Tessa seemed unable to say more, and Ann thought: she must know.

‘It’s my lousy father. He’s packed a bag and moved in with some floozy. It’s been going on for two years apparently.’

‘Tess,I’msosorry.’ ‘It’s a shock.’

‘Ishouldthinkso.Howoldishe?’ ‘Fifty-one.’

‘Andthiswoman?’

‘I don’t know. Some bint from his office. Much younger. What an idiot. But the worst thing is Mum. She’s drinking. I mean drinking.’

‘Ah,Tess...’

‘It’s like she’s making herselfill to make him feel bad. But he doesn’t feel bad—he’s not even there. She rings him up, pissed as an Irish wake, and he says, “Get some sleep.”’

Ann nodded dumbly, stubbing out one cigarette, reaching for another.

Tessa touched her hand. ‘Are you all right, Ann? You seem edgy.’

‘Me.Sorry.No.Tellmemoreaboutyourmum.’

‘That’s it, really. I’m done. So, come on. Your turn. What’s the matter?’

‘Really,nothing.Justfeelingmyage.’ ‘Don’t be daft.’

‘ThirtyinOctober.’ ‘That’s not old.’

‘Okay,I’msex-starved.Willthatdoyou?’

‘No,becauseyoucouldshagCharlie’sbrainsouttomorrow, so why don’t you?’

‘Be serious.’

‘Soitisn’tjustsex,then.’

‘Okay. You’ve got me. I want the real deal.’ She pulled a face.‘Heartsandflowers.Myyoungestsistergotdeckedoutin orange blossom last month. That’s all ofthem hitched, and halfofthem sprogging.’

Tessa was rearranging her big shoulders in a businesslike fashion. ‘So let’s be systematic. Is there someone you’ve missed? Not Charlie, I’ll grant you, but you really should think about Sebastian.’

Annlaughed.‘Tess,giveitarest.’ ‘But he’s nice—’

‘Nice?’

‘And good-looking once you get past the beard and the glasses.’

‘Andthebelly.AndtheDIYhaircut.’

‘But Ann, he’s sensible. Okay, wrong word, what I mean is mature and grown up. He’s got a fabulous smile, and—’

‘So why didn’t you snap him up, eh Tessa, answer me that? Allthosemonthsyousharedanofficewithhim.No,you’reall right, Jack, and you don’t care what rubbish I get.’

Tessa looked pained. ‘Ofcourse I care. And I might have thought ofSebastian, only Jack came along.’

‘Pull the other one. Always with his nose in some book on statistics. Or regurgitating The Times’ leader for want of an opinion ofhis own.’

‘Ann,be fair—’

‘I am being. The Times this, The Times that. Friday, in the pub, he was still droning on about the referendum, for heaven’ssake.Dowereallyneedtoknowthecountinthe Outer Hebrides?’

‘SorryIspoke.’

‘OhTess,don’tbehuffy.You’reright,’Annconceded,‘heis “nice”, as you so enticingly put it, but he never shows any interest in women.’

Tessa didn’t reply. She was fiddling with her glass and glancing distractedly around the bar, as ifshe halfexpected to see someone she knew.

‘Nor men either,’ Ann teased, ‘or Charlie wouldn’t have moved in with him.’

Tessa sat up straight and leant forward. ‘Okay. How about this?’ Her cheeks had flushed pink. ‘Have you thought... whatI mean is... why not have a go at Time Out?’

‘TimeOut?’

‘Yes, you know. Don’t rush to dismiss it. Lonely hearts.’ Howdareshe!‘Ugh!Comeoffit,I’mnotthatdesperate.

AndthemanI’mlookingforisn’tthatdesperateeither!’

Tessa looked as ifshe’d been slapped. For a moment Ann couldn’t think why. Then, ‘Oh my God, was that how you met Jack?’

Tessa was bright crimson now, the flush spreading to her ears, exposed by the savage haircut. ‘For your information, we weren’t desperate, either of us. It’s an efficient way to meet, that’s all. Lots ofpeople do it these days.’

‘Yes,ofcourse.Iwasn’tthinking.Ididn’tmean—’

‘Yes, you did.’

‘No, really. This is far more glamorous than your French evening class. And brave. Tell me what happened. Did you advertise, or did he?’

Tessa was grinning in spite of herself. ‘He did. “Builder with a brain. Short, dark and handsome.” I wrote a letter. He rang. I warmed to his voice. And we met.’ She paused. ‘Here.’

Shegazedroundhappily. ‘Here?’

‘Yes. I came in out ofthe wind, and he was over there, at the bar. And he hadn’t seen me yet, and we hadn’t exchanged photos, but I knew it was him.’

Tessa looked quite unlike herself. Ann couldn’t help smiling. ‘Love at first sight.’

‘No, ofcourse not. I’m not stupid. And please, Ann, don’t say anything. Jack would be ever so cross.’

‘Iwon’tbreatheaword.’

It had been love at first sight, she was realising. And who could blame Tess, because Jack might be short, but he was a real looker. Broad shoulders, dark eyes, dark, wavy hair, and a way of looking right into you. She tried to imagine their meeting, to picture Jack as a stranger in a blue haze of pub smoke, scanning the crowd for the woman he would marry.

It made her jealous as hell, so she thought about Hugh again, to calm herselfdown.

HouseofCards

Thatevening,HughfidgetedbyAnn’sopenFrenchwindowin Camden Town, impatient to distract his thoughts into the discipline ofdealing cards and counting points. It wasn’t fear or jealousy he was battling right now, it was acute longing. He was falling in love all over again. Lois was so vivid, so extraordinary; he ached to look at her. He’d hardly been ableto tear himselfaway from her to come here tonight.

Outside, on the flaking concrete among the weedy, unwatered tubs, Jack and Pamela hovered, their dark and blonde heads bent close, cooking up some private angst. ‘Let’s to billiards,’ he called hopefully.

‘Holdyourwater,Hamlet.We’recoming.’

They showed no sign of it. He sucked in his breath. Oh Lois, Lois.

Ann arrived at his side and leant into him, head against shoulder. He swallowed the lump in his throat. ‘Hello, little Annie. I like your new haircut.’

She lifted her face, exhaling smoke and smiles. ‘Vidal Sassoon.Itcostmeafortune,andyou’retheonlypersonto

notice.Youarealovelyman,Hugh.’ ‘Am I, though?’

‘Definitely.’

‘Thank you, Annie.’ He stepped back to deliver a bow, a hand on the hilt of his sword as he doffed a velvet cap. ‘Evermore thanks, the exchequer of the poor.’ He’d lost his own voice tonight.

‘Hey, where did that man go?’ She swayed on one leg for a moment, mock-pouting, before toppling sideways. Then sighed. ‘I’d better get the table set up.’

DearAnnie,alwaysactingtheclown.Hemovedawayfrom the window and kept his mind busy by watching her. She wasn’t beautiful, but her style made her seem so. Faded jeans and white shirt, silver jewellery, and her chestnut-brown hair, expertly bobbed, bouncing and swinging as she charged around the dank, stuffy room, dislodging dead leaves from the fossilised grape-ivy. She was humming as she bent to fold out the legs ofthe card-table, practically dancing as she shook the cards from their boxes and arranged coasters and ashtrays, all the while giving him quick sideways grins.

She was on strange form tonight, jubilant in a forced way. Butsopale.Sheshouldtakebettercareofherself.Andofthis nice little flat. Jack kept nagging her to ‘get a foot on the property ladder’, but Hugh understood why she hung on here, renting.Itmightbepokeyanddark,butithadcharacter.Itjust needed a good hoovering. A bit ofleafshine, and a break from being kippered in nicotine. And a scrub-down with bleach in the bathroom, where the avocado suite looked grubby and the wallpaper was sooty with mould.

There was noise from the patio; they were coming at last. Jack knuckle-gripped the door-frame, while Pamela whispered and tugged at his sleeve.

Ann heckled them, ‘Come along, you star-crossed lovers,’ and was off again, laughing and spinning on her heel. ‘Hey, everyone’s so uptight tonight. We need to get happy. I’ll fetch more wine.’ She bounded offinto the kitchen, calling, ‘It’ll helpustoaslam,Hughmylover,’inhabitualself-parodyof herDevonshireroots.

‘Anunmakeableslam,’heconfidedtoHoratio.

ThedogwassprawleduntidilyonAnn’sbrown-cordsofa,a largeportionofhisblack-and-pinkstomachdroopingoverthe front. Hecocked an ear, half-waggedhistail,then gruntedand returned to his dreams.

JackandPamelawerestillwhisperingbythewindow.Hugh took a seat at the table and channelled his nerves into cutting and mixing the decks. The activity brought more thoughts of Lois, but safe ones. It was Lois who’d taught him to shuffle like a hustler, interleaving the cards in this satisfying blur of crispnoise.Ittookheratermtomasterthetechniqueandtwo toteachittohim.Shesaiditwasthemostimportantthingshe learned at university, nicely ironic given that she’d refused to play cards ever since. ‘Yawn,’ she’d pronounced when Ann first suggested bridge.

The memory calmed him, making the present seem bearably transient. He was humming, he realised. He’d picked up the tune Ann had left hanging in the air: Let’s face the music and dance. He lifted his eyes from the cards to contemplate the fractured pair who approached the table at last. Jack scowling, drawing heavily on one of his slim, brown cigarettes, his saturnine face, which others thought so handsome, full of ill will. Pamela, her eyes fixed mournfully on the back of her lover’s head.

‘Ja-ack.’

It couldn’t be long. She would see straight, or Jack would put her straight. He was clearly done with her.

Jack produced his winning smile for Hugh, gripping his shoulder. ‘Sorry to keep you, mate. Good to see you. Did you spot my new Rover outside?’

‘Can’t say I did, but then, you know me—car-blind. Areyou pleased with it?’

‘Oh boy, am I ever! Automatic. Huge engine. Three-and-a- halflitre V8. Three-and-a-halfgrand.’

‘It’sgorgeous,’saidPamela.‘Allshinyandgreen.’

‘Camerongreen,’Jackclarified,detachinghimselffromhergrasp.

‘Theinsideiscreamleather,’shesighed.

‘Itsmellsheavenly.’ Jacknodded.‘She’lldoahundredandeighteen,Hugh. Noughttosixtyintenandahalfseconds!’

‘Amazing. What power, eh?’

He didn’t know what else to say. His Vauxhall Viva had been resprayed bronze by the previous owner. Lois hated the colour, but it hid the rust. The inside smelled mostly of Horatio.

‘Benicetome.’PamelaclutchedatJack’selbow.

She’s like a doll, Hugh thought suddenly. Her face was too round, the nose too precisely upturned, the cheeks too prettily pink. Her hair, harsh as spun nylon, was cut in a blondebubble across her brow and the lobes of her ears. She even spoke in a mechanical whine, “Mama, Mama”, a voice like water torture; no wonder Jack had had enough. Her eyes, swimming with tears, were baby blue, fringed with thick, pale lashes. Did they roll when you tipped her horizontal?

Lois had asked after them as he ate his lamb chop tonight. ‘How is it with Jack Sprat and Sugarpam?’

‘Uncomfortable to watch,’ he’d replied. ‘She hangs on like grim death.’

Which had Lois objecting, ‘Why doesn’t he just tell her? What on earth is he playing at?’

Her annoyance seemed curious in retrospect; usually she giggled and pumped him for details. He’d been too busy noticing that she was wearing no bra, while she grumbled on about Jack and Pamela.

‘Lord knows how he got sucked in in the first place. He needs a lesson in taste. How long do you give them?’

‘What, petal?’

Her breasts had been free beneath a blouse he hadn’t seen before: silky-soft, peach-coloured, with small covered buttons.

‘SpratandSugar.Howlongdoyougivethem?’

Her timing was odd. Normally she asked when he got back from bridge.

‘Well, Jack could scarcely be plainer. She’ll have to take the hint soon.’

AtwhichLoishadsmiledenigmaticallyandfetched strawberries and cream.

‘No!’

Theshockofincest.

Jackwasspeaking.‘What’sup,mate?’

Hecouldbarelyanswer.‘I...it...it’snothing.’

He stared at the man. Found himself looking at the dark hair on his forearm. Please, no. It hadn’t happened, not yet. Perhaps he was wrong. Would Lois do that?

‘Ja-ack.’ Pamela could give lessons in pleading. ‘Jack, don’t be cross with me.’

Thebastardignoredher.Grinned.Suckedonhisexpensive cigarette. Said, ‘Hey, let’s draw for partners for a change.’

‘No way!’ Ann erupted into the room. ‘Hugh’s mine! We’re going to win tonight, aren’t we, my lover?’

He didn’t feel like a winner. He tore his eyes from Jack; stretched a hand out to Pamela. ‘Come on, Pam. Come and play bridge.’ Pray God, she had more miles in her. She’d been fun at the start, before she got plaintive. At the start, he’d almost understood what Jack saw in her. He struggled to imagine fancying her, as if this would rekindle Jack’s passion, but he couldn’t manage it. ‘Show us what you’re made of. You know you can beat hell out ofAnnie and me.’

She blinked gratitude through meekly lowered lashes, slid into her seat opposite the still-vertical Jack, and produced one of her mawkish banalities. ‘Lucky at cards, unlucky in love.’ Her forlorn gaze visited her plump white fingers spread upon the stained green baize. Then she fixed Jack with another abject stare. ‘At least let’s be happy when we are together.’

‘Forfuck’ssake,behappythen,foronceinyourlife!’

Thisshockedthemintosilence.Theywereallseatedatlast. Cuttingfordealer,Hughdrewanace.Hedealtrapidly,battling to calm his thoughts, to blot out the idea ofthis man with—

‘ThenewrecruitsarearrivingonMonday.’Heconcentrated on listening to Ann. ‘Two of them are our age. ATP’s been lonelywithLoisandTessagone.Ican’twaittobeinItalywith you all.’

Hugh sorted his cards, biting his lip so hard that it hurt.Did Lois plan to seduce Jack in Italy while he, Ann and Tessa looked on?

‘Tell you what,’ Jack was saying. ‘These recruits, Ann, why don’t you ask ifthey play bridge? Let’s expand to two tables.’

‘Iwill.That’sabrilliantidea.’

‘And we’ll have another go at persuading Tess and Lo, eh Hugh?’ Jack winked at him. ‘I’ll have a good go at Tessa, I promise.’

Hugh sensed Pamela shrink and felt her pain as his own. For, ofcourse, Lois would come now to the Drunken Bridge Club. She would come for Jack and would take him easily, while he watched in silence, as impotent as poor Pamela, as irrelevant as the unknowing Tess.

‘Yes, Jack. I’m not doubting you will,’ he snapped. ‘But now, let’s play, can we?’

PlayingHouse

Zoë Smith slammed the door of her new, glass-fronted oven and saw gravy splash from the plate inside.

‘Curseandsod it!’

A second plateful steamed on the round white table at the far end ofthe kitchen. She stepped over dusty bags ofplaster, plonked herselfon the rush-bottomed seat ofa new pine chair, looped her long hair out ofthe way and began. Chicken casserole,mashandpeas.Surprisinglydelicious.Foronceshe’d cooked something edible, and still Tony didn’t come home.

Shefinishedandpushedtheplateaway.‘SodTony.’

She felt a bit better now; hunger had made her irritable. And there was no mystery to why he lingered in the pub with the other teachers. If she had some half-decent place to go after work, wouldn’t she stay out too? She was as weary as he was ofthis vile house.

Sheshookherhead,refusingthetears.Asshecarriedthe empty plate to the sink, her gaze swam out through the pink primer of the new window-frame into the builder’s tip they called the back garden, a cheerless view in the low eveningsun. When they first moved in, she’d been eager to dig and plant, her hair tied up in an Indian-silk scarf, imagining shrubs andflowersandbuzzinginsects.Tonyhadcomeouttowatch, and she’d smiled up at him, wanting him to share the vision. But what he said was, ‘Sorry, lovely, I hate to be a killjoy, but shouldn’t we concentrate on the house first?’ And he wasright, ofcourse. So now the garden was bricks and junk, and heaps of sand around the black crater of ash and fired nails. Not a growing thing to be seen.

It was she who’d found what was growing. ‘It’s soft here,’ she’d pestered six months ago, poking away at the skirting. ‘Can’t we take up a board, just to be sure?’

‘Oh all right, ifyou must. But do try not to break it. We’ve far too much to do as it is.’

They’d both been afraid. The floor felt weird; something dreadful was lurking beneath it. The difference was that she needed to look and Tony needed not to, as though by not looking it wouldn’t be so. And then, when they looked, he made her feel it was her fault. For looking, for wanting the house.

‘A coat ofpaint and a sunny day, they had you in raptures.’ Thatwasunkind.They’dchosenittogether,hadn’tthey?

Wasn’titasmuchhisfault,toomeantopayforasurvey?

It was true though, the house had been full oflight that first day she’d run down the road with the estate agent’s key in her hand. Sunshine bouncing offwhite walls, a beautiful little house in Balham, south of the river. ‘Come and see!’ she’d enthused, grinning through the dusty panes ofthe phone-box at the leafy entrance to the Common and the shop around the cornerthatwould soon be her shop around thecorner.‘Quick, before it goes!’ Houses seemed to fly offthe estate agents’ lists; there was no time to lose.

‘Ye-es.’ He’d paced slowly from room to room as she jiggledwithimpatience,willinghimtoloveitasmuchasshe did.‘Okay,it’sgotpotential.We’llneedtoreplumbandrewire. And replace all the gutters. But look, Zo, we can knock this wall down, and junk all this pastry round the ceiling. Take out the fireplaces, put in a decent kitchen, install a shower.’

Which meant he was saying yes! And she was so full of excitement that she didn’t think to wonder or argue. And so theyarrived,afterthehoneymoon,wieldingclub-hammersand blowtorches and electric drills, and in no time at all they’d transformed the little house with its small, white Victorian rooms into a grey, dusty forest ofAcro props and jaggedholes and fallen plaster.

Still,thingshadn’tseemedsobad.NotuntilthatDecember eveningwhenshethrewherweightontothechisel,splintering thewood.She’dstolenalookatTony,buthewasbusyfittinga U-bend, head under the sink, bony knees waving in the air.She tried again, easing the chisel beneath each nail as he’d taught her. With tortured creaks, the nails let go. She yanked the board up and off the joists and shone the torch into the void.

Therewasasudden,powerfulsmellofmushrooms.

Beneath the dusty floor, glistening in the torch beam, lay great luscious pools and beads ofhoney brown liquid on pallid, grey-yellow plates offungus.

‘Whatisit,Tony?’Hervoicewasawhisper.

‘Dry rot,’ he muttered. ‘Just a massive, bloody outbreak of lethal, deadly dry rot.’

She had heard ofit, had seen some comedy film when she was a child, which had the bad guys tumbling squealing through a disintegrating staircase before the whole house fell on top ofthem. Now Tony’s DIY books spelt out the reality. They read them avidly, huddled in bed together. Merulius Lacrymans: the weeping fungus. Once it takes hold it creates its own conditions, sucking humidity from the air, seeking sound wood with long, rubbery tendrils that can penetrate evenbrick. You must find it and destroy it, every bit, cut the good wood back at least six feet and souse everything in poisonous spray.Eventhenyoumustprovideplentyofventilation,orit willstartalloveragain.

Terrifyingly accurate: they uncovered grey tendrils snaking up inside the lath-and-plaster walls,heading for the bedrooms. EvennowZoëshuddered,imaginingitburrowingthroughthe newly-laid concrete.

‘We can’t do this, Tony,’ she’d pleaded. ‘We’ll have to get builders in.’

But he wouldn’t hear of it. ‘They cost the earth. And anyway, would you trust them to get it all?’

‘I don’t know. Will we get it all? Can anyone get it all?’ And again she’d crept down the uncarpeted stairs in the dark, to peer into the glutinous depths beneath her kitchen floor.

The slower horror began. Each evening when they got in from work, they ate hurriedly, hardly speaking, changed into their oldest clothes and set to. The kitchen became a quarantine zone into which they stepped with disgust andfrom which they retreated in dread of the spores clinging to their shoes. They burned the rotten wood in the garden, conscious oftheir neighbours’ disapproval, feeling tainted like plague-carriers in old London. It was Zoë’s job to tend the bonfire, and often she lingered beside it, stoking the blaze as high as she dared until the flames, beyond her control, roared up into the night, consuming the infection and drying hertears.

IfTonynoticedthetracksonhercheeks,hedidn’tsay.His expression was grim. He hacked at the beams with robotic intensity, pausing only to light cigarettes or to stub them out savagely on the pale fronds of Merulius Lacrymans, leaving its evil white trails on the beams and the bricks.

Life was primitive without a kitchen, an interminable extension of their wet camping honeymoon in Wales, where she’d learned to carry water from a standpipe and to use the Calor gas ring. In the bedroom she used it again to prepare endless stews in a pressure cooker. Staring about her, waiting for the steam to hiss from the valve, or the kettle to come to the boil for the washing-up, she saw how dust and grime had sulliedtheweddingpresents:thewhiterugfromhergrandma, the chintzcovered armchair from Tony’s mum and dad, the cottonlace bedspread from her aunt. Everything hopeless and grey. And Tony, when she looked at him, was grey and hopeless too, all his eagerness and certainty withered. He’d gone on at her for months to marry him, insisted it would be all right, didn’t she see, ifonly she would trust to fate a little.

Her parents said the same thing. ‘He’s steady,’ pronounced her father, shaking his Telegraph out wearily. ‘Reliable. A bit older than you, I’ll grant, but eight years is nothing, enough to show his potential. Head ofscience already, you can see what you’re getting. You’d be daft not to take him. You’ll be stuck on the shelfsoon—men like Tony don’t grow on trees.’

She saw distaste in her father’s eyes. He was weary ofher impulsive love affairs with fickle men.

‘What’s wrong with Tony?’ her mother whispered in the kitchen. ‘He seems very nice and sincere, and you like him, don’t you?’

‘Yes,butMum,Idon’tlovehim.’

Yet she too was weary ofgetting her heart broken. So one day she stopped fighting, drew a line under the quest and said, ‘Okay, yes, I will marry you.’

‘GoodGod,Zo.’Tony’smouthhaddroppedopen.‘Doyou mean it?’

‘Yes,Ido.’

And amazingly she found it was true. The worldbrightened. She felt safe and happy. And they were happy, making their vows, holding hands under the tablecloth at the reception. She was trying to smile now, but it was no use, this memory. It was true in a way, but not in so many others. She still hadn’t loved Tony when she married him, and she knew now that she never would, not as she wanted to love a husband. It was her fault, not his, but knowing that was no help.

She turned back from the window. The kitchen smelled of congealing stew, not ofhorrible, toxic chemicals. The rot was ripped out, burned, all traces buried under four inches of concrete,yetstillshesniffedandprodded,andwoketerrified

from dreams in which it burst through the new tongue-and- groove panelling.

She bent to touch concrete, as though it might offer an answer. Something had shifted in her head. Not Tony’s fault: was that it?

Her job hadn’t helped. Musty corridors, chalk-dusty professors, her desk in a broom-cupboard with a barred view ofmoss and slime and pigeon shit. The university deserved dry rot but was too posh to catch it. And at last she was gone from there! Heading for ATP on Monday, which wasn’t at all posh: yellow brick, steel and glass, five floors up with an outlook of sky and chimneypots. With smells of coffee and cigarettes and Xerox ink. And the people mostly young, wearing jeans and short skirts. Yes—

But here was Tony back. The unsteady scratch of his key, the clunk as the door shut, the sound ofhim in the hall. Her spirits deflated. It wasn’t his fault, no, it wasn’t at all, but that didn’t mend it.

He stumbled into the kitchen wearing a sheepish grin. ‘I’m sorry, Zo. I only meant to have one.’

And she was hushing him, smiling, trying to make him smile too, though he wouldn’t. ‘It’s okay, don’t be sorry. I’ve been wrong to be cross. It’s fine to get out. You’re right to get out. I should get out more myself.’

FalseMove

As she turned off the Aldwych on Monday morning, Ann concentrated on feeling positive. She always enjoyed this walk up Drury Lane. Narrow and meandering, it still was a “lane” despitethemodernfrontageofthetheatre.Thelittlespecialist shops with their dusty display windows spoke of the past. When she’d first sashayed up here seven years ago, the only one ofher family to get a degree and leave Exeter, she’d felt shiversofjoy,fancyingherselftobewalkinginNellGwynn’s footsteps, destined to rise in the world and to win some great man’s heart.

She was passing the coffee merchant’s now, the smell of fresh grinding was delicious, and ATP was in sight against the morningblueofthesky.Inthenext-to-topstoreyofthe