Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Penned in the Margins

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

*SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2021 FORWARD PRIZE FOR BEST SINGLE POEM* From the mercurial mind of award-winning poet John McCullough comes his darkest and most experimental book to date. Panic Response puts personal and cultural anxiety under the microscope. It is full of things that shimmer, quiver and fizz: plankton glowing at low tide; brain tissue turning to glass; a basketball emerging from the waves, covered in barnacles. These are poems of uncertainty but also of hope, which move beyond the breathlessness of panic towards luminescence and solidarity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 37

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PANICRESPONSE

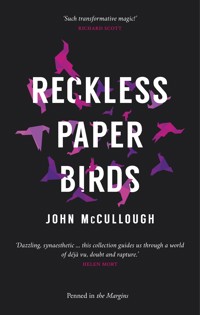

John McCullough lives in Hove. His third book of poems, Reckless Paper Birds (2019), won the Hawthornden Prize and was shortlisted for the Costa Poetry Award. His previous collections have been Books of the Year for The Guardian and The Independent. He teaches creative writing at the University of Brighton and for organisations including the Arvon Foundation.

ALSO BY JOHN MCCULLOUGH

POETRY

Reckless Paper Birds (Penned in the Margins, 2019)

Spacecraft (Penned in the Margins, 2016)

The Frost Fairs (Salt Publishing, 2011)

PUBLISHEDBYPENNEDINTHEMARGINS

Toynbee Studios, 28 Commercial Street, London E1 6AB

www.pennedinthemargins.co.uk

All rights reserved

© John McCullough 2022

The right of John McCullough to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Penned in the Margins.

First published 2022

ePub ISBN

978-1-913850-09-8

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

Glass Men

J

Electric Blue

Quantum

Candyman

Letter to Lee Harwood

Prayer for a Godless City

Pour

Mantle

A Chronicle of English Panic

,

And Leave to Dry

Scoundrel

Error Garden

Invisible Repairs

Flower of Sulphur

Coombeland Mannequin

Worms

Scrambled Eggs

Oops, I Did It Again

Self-Portrait as a Flashing Neon Sign

&

Inside Edward Carpenter

Old Ocean’s Bauble

Bungaroosh

Six!

Mr Jelly

Crown Shyness

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NOTES

for Morgan and my parents

Panic Response

Glass Men

Brain tissue inside a man’s skull at Pompeii had turned to glass through heat.

When my head is molten, I hide with ice packs near an electric fan.

A therapist suggests my overworking began as a way to please a disappointed father.

Charles VI of France believed he was made of glass.

I have no wish to blame my father, who has his own private volcano.

When glass fractures, the cracks leap faster than 3,000 miles an hour.

My father’s running medals hibernate in boxes on a shelf.

In fight-or-flight mode, blood gushes to muscles, hyperventilation flaps its shadow.

My body prepares to race north to the Arctic, across the sea.

The smartphone may be said to function as an apex predator.

No shelter withstands repeated storms of ash.

Laying the predator facedown will not save anyone.

To build a short-term haven, I inhale slowly, sweeping arms above my head.

At my best, I end text messages to Dad love John.

Small refuges with walls of air can, on occasion, seem enough.

I write this while my hands are shaking.

J

And so it starts, though I cannot.

Despite my being unable to say the first words

there is a voice doing it, this not-speaking.

There are risks. Even now, Marie Curie’s notebooks

are so radioactive no one can hold them.

Likewise, there are phrases that I (whoever this is)

am reluctant to approach, to slide from their lead-lined box

in case my skin candles to green, words I cannot form

without a chance of my teeth falling out.

Books can kill you. I know this.

I read and read and woke one night with a clawed hand

squeezing my brain. I stumbled to the bathroom

past a tower of loans from a library’s Renaissance corner.

I had dissected every text, by which I mean I incised

their skins then weighed their organs in my palms,

warm kidneys, spleens and lungs,

till each went cold and I realised I’d been removing

pieces of myself, a little at a time.

My throat closed and the sound wouldn’t rise.

No one could get within a hundred miles.

I grasped my phone and all that fell from my lips

were the noises of a failed genetic experiment:

the grunts of a boar, an owl’s screech

as it heard its own limits.

I lay curled in an armchair for weeks

staring at my hands, my skin so sheer

I split open at the lightest brush

of sound. I became a vessel of many silences:

the quiet of a locked room, braided

with the nearly-not-there of a tree;

a pause in a quarrel, tongue cropped

with one flick of a wrist.

I had to learn to talk again, practised

for hours shaping J, a narrow tunnel