Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Emma Press Prose Pamphlets

- Sprache: Englisch

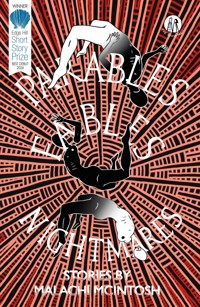

Winner of the Edge Hill Short Story Prize 2024, Debut Collection Award A man jumps, the platform empties, then the stories begin. Filled with tales of tragedy, love, hope and frustration, Malachi McIntosh's debut collection of short stories offers surreal and satirical accounts of the many perils of contemporary life. From resistant mothers and unexpected corporate climbers, to doomed weddings and unwelcome visitors, these dark, comedic and uncanny stories contend with timeless concerns of parenthood, family, race and identity in the here and now. Whether characters are absorbed in social media or burying their grief, raising themselves up or taking others down, Parables, Fables, Nightmares brings a light to our interactions in an ailing world and heralds the arrival of a unique new voice in fiction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 120

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISEFORPARABLES, FABLES, NIGHTMARES

‘Malachi McIntosh conjures worlds that lie at the extremes of our imagination and at the center of our experience. The parables are visceral and unsettling, beautiful and charming, all at once. Every character stands out as much as they are a stand-in for a stereotype; their chatty bonhomie is captured with absolute finesse. This book is a delightful read...’ Meena Kandasamy

OTHERTITLESFROMTHEEMMAPRESS

SHORTSTORIESANDESSAYS

Blood & Cord: Writers on Early Parenthood, edited by Abi Curtis

How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart, by Florentyna Leow

Night-time Stories, edited by Yen-Yen-Lu

Tiny Moons: A year of eating in Shanghai, by Nina Mingya Powles

POETRYCOLLECTIONS

Europe, Love Me Back, by Rakhshan Rizwan

POETRYANDARTSQUARES

The Strange Egg, by Kirstie Millar, illus. by Hannah Mumby

The Fox's Wedding, by Rebecca Hurst, illus. by Reena Makwana

Pilgrim, by Lisabelle Tay, illustrated by Reena Makwana

One day at the Taiwan Land Bank Dinosaur Museum, by Elīna Eihmane

POETRYPAMPHLETS

Accessioning, by Charlotte Wetton

Ovarium, by Joanna Ingham

The Bell Tower, by Pamela Crowe

Milk Snake, by Toby Buckley

BOOKSFORCHILDREN

Balam and Lluvia's House, by Julio Serrano Echeverría, tr. from Spanish by Lawrence Schimel, illus. by Yolanda Mosquera

Na Willa and the House in the Alley, by Reda Gaudiamo, translated from Indonesian by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Kate Wakeling, illustrated by Cecillia Hidayat

We Are A Circus, by Nasta, illustrated by Rosie Fencott

Oskar and the Things, by Andrus Kivirähk, illustrated by Anne Pikkov, translated from Estonian by Adam Cullen

Cloud Soup, by Kate Wakeling, illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa

for Miles

THEEMMAPRESS

First published in the UK in 2023 by The Emma Press Ltd.

Text © Malachi McIntosh 2023.

Cover design © Mark Andrew Webber 2023.

Edited by Emma Dai'an Wright.

All rights reserved.

The right of Malachi McIntosh to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-915628-19-0

EPUBISBN 978-1-915628-17-6

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

The Emma Press

theemmapress.com

Birmingham, UK

There is little like knowing

I am an orchestra –

only rehearsing

– VICTORIA ADUKWEI BULLEY,‘What it Means’, Quiet (2022)

CONTENTS

*

Examination

The Ladder

Limbs

Mirrors

White Wedding

The Mature Student

Saint Sebastian Mounts the Cross

roads

Notes

About the author

Other titles from The Emma Press

About The Emma Press

*

She arrives late at Bank station when the man decides to jump. She’s meant to meet Matthew at the Tate Modern for their second date. So far, she’s been lukewarm on him – but this time she has more hope, wants to rush home, change; gets waylaid at work running through, yet again, her PowerPoint presentation for Department Day, and hits the platform as the train comes in and the man next to her is gone.

Just gone. No leap or run or scream. No sign or sound except the sound. Just gone, like he never was.

And it takes the commotion of everyone else to even realise that it’s even happened at all.

When she leaves the station it’s with bodies in procession. Everyone with their phones out waiting for the first few bars of signal, then calling and texting, the tannoy apologising for The delay to your journey, Underground staff out and redirecting and enough people complaining about the hassle that it almost – doesn’t – counterbalance the look on the faces of the people who saw.

But she didn’t see. She stands out in the street as it was, in the city as it was.

She was right there next to him, standing there right next to him, but she didn’t see.

Matthew texts her as she walks nowhere, rings her when the time for them to meet comes and goes and she’s done three laps of an anonymous block and she answers finally and tells him A man He jumped And I saw it, even though she didn’t see.

She didn’t see.

And from then on whenever she talks about it – and she develops a special way to move into it, the story, to precede it, a kind of half-laugh that’s not a laugh at all to end it – she’ll make a face and pause and say, ‘You know once,’ and say she saw it when she didn’t see.

She didn’t see.

She always says that she did, and she never knows why she does. But she does it anyway.

I

Examination

They slept together in the same bedroom, but no longer shared the same bed. She’d told him over a year ago that it wasn’t appropriate (her word, ‘appropriate’), and bought him a camp bed, just to start, and wedged it against the far wall. The arrival of the bed meant the loss of the bookcase from the bedroom, the books now stacked, alphabetically, underneath where he slept.

They tended to wake up at the same time, her alarm clock bleating to them both, prodding each body up and out as it echoed. In summer the noise rang with sunlight; in winter the sound into the dark. Today it was set earlier than always, because today was today: the test.

The boy lay awake. His eyes opened about an hour before they were supposed to, found the ceiling and rolled into his eyelids as he started doing his sums. He began with the easy ones – the ones he knew he knew – then moved upwards into big numbers: three digits, four. He did as she taught him, checked his answers with subtraction, did everything twice, but then he got stuck, as always – he always got stuck.

He looked down, then, across at her sleeping, over the distance from his bed to hers. In the first weeks of lying alone he would, inevitably, wake up in the dark and suddenly feel cold, feel the idea sliming out of him that she’d decided to run away. He’d look across and in those first weeks, months, panic and throw off his sheets to see her, sneak the few steps to her blanket and burrow in. She’d stir and mumble and move her hands, but if he pulled his knees into his chest and stayed silent, breathed even, he knew he’d spend the evening in her heat, with her smell.

‘Are you awake?’ she said to him now.

‘No,’ he said, eyes open. ‘Not yet.’

She made a noise, a yawn, slid up and back to rest on her forearms in bed.

‘Can you boil some water for some tea?’

‘Can I make the tea?’

‘Just the water.’

She breathed another noise, a sigh or a yawn.

‘You make it too weak. I have to teach you.’

She yawned again, sat her back fully against the headboard, her arms up then out – stretched – her face twisted up, and then her face at rest.

‘Do we have to go?’ the boy said.

Her arms slumped into her lap.

‘I’m so tired. I don’t know why I’m so tired.’

‘Mom?’

‘Of course.’

‘Of course what?’

‘Of course we have to go.’

‘Why?’

‘Because we do.’ Her hands smoothed down her face, back through her hair – her hair everywhere. ‘Because they all think you’re something that you’re not. And because of that they think we’re something we’re not. And we’re going to show them.’

‘I don’t want to show them.’

She looked at him, yawned something he couldn’t understand. And then the alarm went off.

*

The subway. Every week it felt like a million miles into and out of the city: the walk to the subway, the walk to the apartment, the walk up the stairs.

She’d met with his teachers so many times in the last two years it had turned into a second commute. Home. Smear a sandwich. Check the answering machine. Feed him, then drag him back to the bus, to the school. First, the tight smiles. Small talk – your trip – oh really – your work – i have a cousin who – coffee? – oh tea? i’m not sure we have tea – Then the warmup – we think your son is very capable – then business.

Eventually even they felt the routine was too routine and wanted to break it, to cut to the chase – they’d say that, ‘I want to cut to the chase’, gesturing with clenched fingers, now presenting themselves as no-nonsense, frank – people who spoke the truth and expected it back.

All the approaches aimed anyway at the same destination: whether they claimed to think he was capable or not, what they wanted, why she was there, was for them to tell her the myriad ways that he’d failed. Every time she met them, eventually, a white paper of red lines, a quotation from a parent of another child, his own admission, ‘yes’. He was variously inattentive, disruptive, unsettled, troublesome, agitated, over-excited, rambunctious, too vocal, undermotivated, uninterested, volatile and, once, dangerous.

‘Dangerous?’

‘I don’t say that very often,’ the woman said, tapping her pen on the desk between them. ‘But that’s the best word for the way he behaves.’

She would be called in to discuss his report cards, to discuss his ‘harassment’ of girls his age, his refusal to stay in his chair, the wide eyes he directed everywhere except at the blackboard. She’d be asked what he watched on television, where he was in the few hours before she arrived back home from work; they’d question – ever so tentatively – where his father was – he’s nine now, they said most recently, softly, and for a boy his age it’s very important.

She’d nod at them. Take him home, scream at him. Sit him down with his schoolbooks on the kitchen table, just the two of them under the single bulb, teach him. Take him back the next week – walk bus walk – see the same old homeless man on a cart begging for change, the kids on Walkmans with skateboards, other women with their sons on bus seats reading thick books opened up on their laps. Him and her.

*

They ate breakfast together, her leg bouncing underneath the table out of sight.

‘Can you do two times ten?’ she said.

‘Twenty.’

‘Good. Ten times two?’

He paused, smiled. ‘It’s the same.’

‘Four hundred twelve. Plus. Nine hundred and sixty.’

His eyes stared at some point beyond her body, his mouth slowly sliding open.

‘Two. Seven.’ He used his fingers. ‘Thirteen. One three seven two?’

‘Say it properly.’

‘One thousand three hundred and seventy-two?’

She paused and counted on her own fingers. ‘Good.’ She nodded.

He nodded too, grinned, spooned cereal and chewed.

‘They’re going to ask you a lot of questions like that. Most of them will be harder.’

‘I know.’

‘Some will be really, really hard and they’ll all be looking at you, maybe more than one person, but you have to do all of them, even the hardest ones. Okay?’

‘Okay.’

‘Are you scared?’

‘A little bit.’

‘Me too.’

*

He’d been expelled. Another problem with a girl, this time in his Thursday lunch. The story, as they told it, was that he had placed his hand, palm upward, on the bench where she was about to sit. When she was almost seated he grabbed her, she jumped and spilled her lunch and drink all over her dress. He laughed at her, covered in food slush, and she slapped him in the face.

Three adults in the principal’s office. The boy at home. She’d come in to the principal’s message on the answering machine, rang back to confirm, tonight, boiled spaghetti for her son, headed out of the house alone, only twenty-five minutes after she got in.

‘You all work so late,’ she said when she arrived.

All they did was stir.

She said nothing to the boy that night when she returned besides what was necessary: Turn it off, Brush your teeth. In the morning she waited until after he was dressed to tell him he wasn’t allowed at school anymore. She asked him if he knew why and he squirmed and said ‘no’. That set her off. She grabbed his t-shirt and shook him, asked him again and he said ‘no’, welling up. She left their bedroom, grabbed her slipper, grabbed him again and smacked him on his legs and his back and his head until her arm went numb. She left him crying on the kitchen floor. Sat on the floor of her room, cried too.

The principal tried to be nice, brought her coffee, sent his assistant or administrator, one of the ones she’d already met, to fetch it. Well, he said, I’m sorry, but we’ve had enough. He tried to be nice, said the best option might be a special school, mainstream education might be too much, and offered her tissues. He didn’t say anything about the boy’s father, but did, on exit, ask: ‘Are you working right now?’

*

Think the two of them, walking to the subway, the boy’s hand inside his mother’s hand. A cityscape of uncollected trash bags and low buildings, more kids on skateboards. The boy walking beside her to the bus, practicing sums, trying analogies like man is to arm as bird is to __________; up is to down as left is to____________; past is to future as now is to _____________.

They reach the subway and she pays for tokens, the boy watching her face.

‘What are you looking at?’

‘You.’

‘Mind your business,’ she says.

‘I am.’

She smiles. ‘Are you nervous?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t be nervous. You’re ready. What’s the capital of New York?’

‘Albany.’

‘See? Good.’

‘But I’m scared.’

She frowns, chews the inside of her bottom lip and walks with him down to the platform. Three trains come for the opposite direction before their train pulls in. They find seats, sit, the subway car empty, rattling, advertisements. The train makes its way, first above ground and all the rooftops, then into the tunnels.

A long pause. Then she says, ‘Don’t be.’

*

They emerged together from the subway into cold sunshine, tired after changing trains twice. She’d asked them if there was anywhere closer, but the people who called her said no, there were only a few test centres, only one open on weekends.